14

Maori References to the Field of Arou

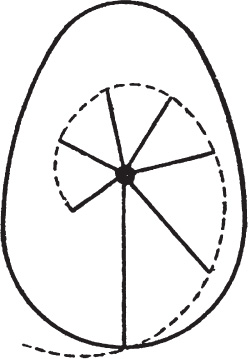

In the prior volume of this series, The Mystery of Skara Brae, we discussed a series of megalithic sites on Orkney Island in Northern Scotland that date from the Neolithic period, around 3200 BCE. In our view, these sites were meant to illustrate, on a human scale, the progressive stages of the formation of matter. We know the sites were interrelated because they were linked to one another in Neolithic times by a road, which due to the placement of the sites traced the shape of a large counterclockwise spiral around intervening bodies of water. The spiral calls to mind a Dogon figure that, on one level of interpretation, characterizes their egg-of-the-world. We have said that from one perspective, the egg is compared to seven rays of a star of increasing length, and the spiral is drawn to inscribe the endpoints of those rays.

The spiral within the Dogon egg-of-the-world (from Forde, African Worlds, 84)

The Orkney Island road, which was set beside a body of water called Stenness, began at a standing stone called the Watchstone of Stenness, then led to a megalithic stone circle known as the Standing Stones of Stenness. The road continued on to a once peaked (now domed) burial chamber called Maes Howe and then ultimately onward to a cluster of eight stone chambers or houses that constituted the tiny farming village of Skara Brae. The progression of figures that are enshrined in stone on the island coincides with the sequence of geometric shapes that underlie matter and that, for the Dogon, generate the clustered dimensions of the egg-of-the-world.

However, the full Dogon concept of this progression includes developmental stages for matter that go several steps beyond the chambered egg. In the mind-set of Dogon cosmology, the next conceptual stage relates to vibrational frequencies that define fundamental particles of matter and that differentiate them from what modern astrophysicists refer to as “the background field.” Each year at the time of the planting of seeds for a new agricultural season, the Dogon illustrate this concept symbolically by drawing the figure of a circle in the middle of the agricultural field of their highest-ranking priest, known as the Arou Priest. Next, they fill the circle with a series of zigzag lines that symbolize the vibrational frequencies of these particles. Because the field belongs to the Arou Priest we refer to it as the Field of Arou. This Dogon practice suggests that the Orkney Island symbolism might have actually extended beyond the cluster of eight houses at Skara Brae and on to the agricultural field that is understood to have adjoined them.

On one conceptual level, it is clear that the Field of Arou represented a cosmological concept and was meant to be understood symbolically. However, on a second level of understanding, it also constituted an actual physical field that the Dogon planted with seeds and cultivated to grow food. In The Mystery of Skara Brae, we were exploring possible ancient Egyptian influences on Orkney Island, and so it made sense to look for possible Egyptian correlates to this Dogon concept. One Egyptian word for “field” was given as sekhet or skhet, and dictionary searches based on that word turned up a comparable Egyptian concept called the Sekhet Aaru. Budge, in his Egyptian Hieroglyphic Dictionary, interprets the term Sekhet Aaru to mean “Field of Reeds,” a term that defines the Egyptian concept of an afterlife. This was also the concept on which the later Greek notion of the Elysian Fields was based.

Like the Dogon Field of Arou, both Greek and Egyptian sources treat the concepts of the Field of Reeds and Elysian Fields on two conceptual levels—as a mythical concept, but also as an actual physical locale. Ancient texts that provide details of the physical locale describe it in terms that also correctly describe Orkney Island. It is portrayed as an idyllic white island located along the edge of the Western ocean, a place of great winds surrounded by ocean inlets and intimately associated with an agricultural field. The language used in some of the texts also evokes Orkney Island. The locale is actually referred to by the Greek poet Pindar as Okeanos. The term Elysian could well be formed from a root word that means “island.” Ancient Scandinavian names for Orkney Island were Argat and Orkneyar. Based on Dogon and Egyptian references, we associate the island with the terms arou or aaru and with the phoneme ar.

The effort required to conceive of, design, and raise the series of megalithic structures on Orkney Island suggests that it must have been a significant center of culture, civilizing skills, and knowledge in Neolithic times. Perhaps reflective of that view, a Maori word aroa that means “to understand” takes a phonetic form that is quite similar to arou.1 Likewise, there are attributes of the site and its known history (which we cite in The Mystery of Skara Brae) that link it conceptually with Dogon and Buddhist notions of ancient civilizing instruction. The accepted archaeological dating of the Skara Brae site at around 3200 BCE is, developmentally speaking, too early to reasonably reflect distant influences of dynastic Egypt, and yet many of the symbolic aspects of Orkney Island fall directly in line with Dogon and Egyptian cultural elements we have been exploring. An alternative viewpoint, based on Dogon and Buddhist claims of instructed knowledge, is that Orkney Island may have constituted a campus-like instructional sanctuary whose educational benefits ultimately flowed in the reverse direction: from Orkney Island toward the agriculturally based monarchies that are known to have arisen in various regions of the world during the period just following 3200 BCE. From that perspective, Egyptian ancient concepts of heaven (in the form of the Field of Reeds and its companion, the Field of Offerings) can be seen to align with those of any successful college student who may have been truly fond of his or her educational experience and so might have difficulty imagining a better environment to return to after death than the one that had been enjoyed during the years of study.

Attributes of the nearby Faroe Islands, which are situated a short distance to the north and west of the Orkney Islands, suggest that they might have served as a kind of safe haven for the theoretic instructors of this Neolithic tradition. In support of that view, the ancient Egyptian word for “pharaoh” (per-aa) originally referred to a place, not the person who lived there. Meanwhile, the Faroe Islands themselves offer a number of different natural defenses against unwanted visitors and so in our view would make an excellent home base for any knowledgeable group who might have organized this ancient instructional effort. Likewise, there is no currently accepted academic theory for the origins of the Egyptian pharaohs. No one knows with certainty where they came from, which cultural tradition they represented, or precisely how they came to power sometime after 3100 BCE in Egypt. The earliest kings from widespread regions of the world claimed a right to power that was ostensibly delegated to them from “gods.” Such statements could make sense if one purpose of the Orkney Island site was to train leaders for regional monarchy and for the priesthood.

Another Dogon cosmological term that is applied to the spiral of matter associated with the egg-of-the-world and to aligned shrines comparable to a Buddhist stupa is arq or ark. In The Mystery of Skara Brae, we associated this phonetic root with an archaic name for Orkney Island, which was Argat. Similar phonetics can be seen in the name of an Egyptian sanctuary: arq-hehtt. The phonetics of these words helps us put in perspective a Maori title for priests previously mentioned, which Tregear gives as ariki. However, the Maori word also carries a second meaning that has mythic significance for ancient Egypt, most obviously in regard to the biblical story of the Exodus from Egypt, which is “firstborn.” The term “firstborn” was also a title of the high priest of Ptah. Linguistics provides us with a similar possible linkage to the much earlier era of Gobekli Tepe by way of an Egyptian word tepi that also means “firstborn.”

We associate the term Sekhet Aaru with Orkney Island, but also most specifically with the agricultural field that would have adjoined Skara Brae. In ancient Egypt, the Field of Reeds was described as having been positioned nearby what is called the Field of Offerings, or Sekhet Hetep. From a cosmological perspective, the concept of an offering as a thing “given” arguably relates to the notion of a dimension, a concept that is treated as a given in creational science. Geometric figures such as a point, a line, a space, and mass that we associate with the Orkney Island megalithic structures also bear a relationship to the concept of dimensions of matter.

The Egyptian word skhet can refer to the spiral shape that defines the progressive stages of matter. We noted in China’s Cosmological Prehistory that the ancient Chinese term for this same structure is given as haohao. For the Maori, the concept of a “religious offering” is expressed by the similar word hau. Tregear states as a prelude to his dictionary entry for the word hau: “This word is an exceedingly difficult one to arrange or classify under different headings. Many of its meanings seem sharply distinct from the others; but those who read the comparatives carefully will see that it is almost impossible to tell where one meaning merges into another, or where a dividing line could be drawn. Thus the sense of cool, fresh, wind, dew, eager, brisk, famous, illustrious, royal, commanding, giving orders, striking, hewing, etc. all pass into one another. Therefore, with regret, I have to group all of the meanings of hau together.”2

Clustered meanings are one of the signature features of terms of the cosmology. Maori meanings for the word hau touch on a variety of aspects of climate, instructed agriculture, and the fostering of kingships that we associate with Orkney Island.

We have mentioned that the archaic tradition that we believe descended from Gobekli Tepe was a matriarchal one, characterized primarily by Mother Goddesses. Within a few centuries of the beginning of the dynastic era in Egypt, reversals in cosmological symbolism occurred that resulted in the predominance of Creator Gods over Mother Goddesses. From this perspective, the Maori religion, which is largely characterized by gods such as Tane and mythic cultural heroes like Maui, who was thrown into the sea as an infant and saved by the ocean spirits, reflects a cosmological mind-set that is consistent with the historical era following 2600 BCE, rather than the earlier archaic tradition. So it seems reasonable to think that the Maori may have been among the cultures who were influenced by Orkney Island instruction. If so, then we might expect to find surviving cultural references to the era of Orkney Island instruction among the Maori. And, in fact, it seems that we do.

Words that arguably bear a phonetic relationship to the Dogon and Egyptian words arou and aaru define key cosmological concepts within the Maori tradition. The first of these, pronounced ahurewa, refers to “a sacred place.”3 In his dictionary entry for the term, Tregear refers the reader to the phonetic roots of the word: ahu and rewa. Comparable to the Dogon and Egyptian phonetic root ar, which implies the concept of ascension and is symbolized by the notion of a high hill or a staircase, the Maori term ahu means “to heap up” or “to foster.” The Maori word rewa means “sacred.” Together the words express a concept that may be an effective equivalent of the ascending stages of creation that we associate with the term arou, the idea of the upward fostering of the sacred. We have mentioned previously that the term ara means “to rise up” or “to awake,” definitions that relate directly to the cosmological concept of the ascension of matter.4 The idea that the Orkney Island complex of Arou might have played an instructional role in ancient times may also be reflected in a Maori term aroa, which means “to understand.”

In The Mystery of Skara Brae, one of the first positive links we were able to make between the structures on Orkney Island and the Dogon creation tradition rested with the form of the Neolithic houses that are found at Skara Brae. The plan and construction method of the earliest of the Skara Brae houses, characterized by local Scottish researchers as including “unique” features, is an outward match for a traditional Dogon stone house. As the Dogon understand the architectural form, it is meant to replicate the body of a woman who is sleeping. The structure includes a round room at one end that symbolizes a head, two rectangular sleeping areas on the side that represent arms, a central room with a hearth that represents the body cavity and heart, and a doorway at the other end that represents the woman’s sexual parts. The idea that a Dogon house would relate symbolically to their system of cosmology seems particularly sensible, since one of the generic metaphors by which symbols can be classified within the Dogon system is correlated to four stages in the construction of a house. So it seems significant that a Maori term that means “to build or erect a house,” ahuahu, bears a close phonetic resemblance to the term Arou, or Aaru, an ancient name we apply to the place where we believe this symbolism originated.

Tregear explains that another Maori name for the region of Ahurewa is Naherangi, meaning “blow softly as the gentle breeze; place where the wind comes from.” Windiness is one of the characteristic aspects of the climate at Orkney Island, and it is also cited in ancient Egyptian and Greek texts as a signature attribute of the Field of Reeds and of the Elysian Fields.

When the agriculturally based kingship of the First Dynasty took hold at Abydos in Egypt sometime after 3100 BCE, it made its appearance in association with a temple-based academy called the House of Life. If we endorse an interpretation of Orkney Island as a kind of instructional sanctuary, then it is possible that the Egyptian concept of the House of Life was intended to provide continued instruction to priestly initiates of the cosmological tradition, comparable to what appears to have been offered on Orkney Island. The Maori culture established a similar temple-based school of instruction at the temple of Wharekura. In his dictionary entry for the term, Tregear states that it was “a kind of college or school in which anciently the sons of priest-chiefs (ariki) were taught mythology, history, agriculture, astronomy, etc.”5

Dogon concepts relating to their field of the Arou Priest have meanings on both physical and mythic/cosmological levels of understanding. The same is true for how Egyptian sources treat the concept of the Sekhet Aaru, or the Field of Reeds, and how Greek writers presented their concept of the Elysian Fields. Some references fall in the realm of cosmology, while others seem to be given in relation to specific real-world geography. So we would expect the same could be true for any related Maori references. Both in his dictionary and in other works, Tregear discusses the mythic-versus-real duality that surrounds the fabled Maori homeland of Hawaiki, and more particularly in regard to the great temple of Wharekura that was said to have been located there. He also felt that the consistent use of the same term, wharekura, in relation both to the actual temple and to schools in New Zealand added to the confusion.6

In his book The Maori Race, Tregear comments that, in the Cook Islands, concepts of this Maori homeland seem closely associated with the Spirit World. He also remarks about the close real-world proximity in which the Upper World and Lower World seem to take their placement in some Maori myths. For example, in one myth a character is able to view the cliffs of the Upper World from the Lower World; in another, the great winds of the Lower World lie just below the feet of characters of the Upper World, who can look down and see “fire, men, trees and ocean,” as well as people going about their real-world pursuits. Several of the Faroe Islands are characterized by vertical cliffs that rise hundreds of feet upward from the surrounding ocean passages. Almost daily, whirlwind-like storms make their way through these passages, but with effects that are almost unnoticeable from the clifftops of the islands. People who stand atop one of these islands can quite literally look down on activities occurring below them. Once again, both the geographic and meteorologic attributes described in the Maori myths match characteristics of the Faroe and Orkney Islands in Northern Scotland.

The Maori term mu refers to “an ancestor of the Maori,” while the Maori term mua refers to “the front” or “forepart” of something.7 These meanings align well with the Egyptian word mu, which referred both to a person’s female relatives and to the concept of an ancestress. Also, as with many ancient cultures, the Dogon conceptualize the era of the past as being “ahead” of us, rather than “behind” us, as we think of it in the modern view. An example to illustrate how the concept was perceived is that of a bus filled with a person’s genetic ancestors, where the oldest (those who metaphorically “get off the bus” first) are seated at the front. From that perspective, the “future” conceptually follows (or is behind) the “the past.” Tregear defines the related term mua as “a god worshipped in the temple of Wharekura.”

Supportive of the outlook of a possible relationship between the temple of Wharekura of the Maori and the Egyptian temple-based concept of the House of Life, the Maori term whare means “house” or “hut”8 and the word kura refers to the “color red.”9 However, kura also refers to a kind of red grass used to form wreaths that were worn by the mythical Maori Chiefs of the Migration, those who ostensibly led the Maori to New Zealand. A myth tells of how, after one of these wreaths was thrown into the water, the red grass it was woven with took root and spread. That grass is said to still be found growing near the city of Auckland. The strong implication is that the word kura refers to “red reeds” of the variety from New Zealand. From that perspective, the Maori term Wharekura could be interpreted to mean “House of Reeds.” If that interpretation is a correct one, then the symbolism could well be to the inferred school at the Field of Reeds on Orkney Island, whose cosmology inheres in the architectural form of a house and which was seemingly replicated at the Maori temple.

The earliest Scandinavian visitors to Orkney Island reported encountering two groups of residents living there. The first were described as pygmies of strange habits called the Peti, and the second were a group of clerics called the Papae, who were said to always wear white. In The Mystery of Skara Brae, we presented evidence to link the Peti with a group of mythical teachers of the Dogon called the Nummo, who were credited with having instructed the Dogon in skills such as agriculture. Some references that may pertain to the Peti describe them as a group of sorcerers, while others seem to link them to the ancient Scottish descriptions of fairies. We associate the Papae with the Dogon themselves, who are commonly characterized as a priestly tribe. Dogon sources describe the Nummo as having a need to always be nearby bodies of water. In Maori mythology, the name Petipeti referred to a “marine deity” who was considered to have been an ancestor to the Maori priests.10 The Maori term papa can mean “father,” a term that was traditionally applied to clerics and priests in Scotland. The word is based on the phonetic root pa, which refers to a mythical “god who presided over consuming food.”11