Cairo, spring 2005, not far from the Arab league headquarters. We are stuck in traffic, two Egyptian friends and I, and a man pushing a handcart walks past our stopped car. On his cart, those little bobble-headed dogs that grace the dashboards of many cars in the United States and elsewhere. He calls out in Egyptian Arabic: “These are a gift from America! America wants you to have them!”

I’m confused. I ask my friends to explain. They instruct me: “America sends us lots of things we don’t want. The man is using the joke to sell his objects. You may not want them, but America tells you to want things, so please take a look at these.”

“But people know the bobble-head dogs are made in China, right?” I ask.

“Yes, of course. That’s not the point.”

THE SEQUENCE OF EVENTS that has come to be called the “Arab uprisings” was clearly a turning point in the history of the Arab world. Since the events of January and February 2011, countless articles, books, special issues, and now anniversary accounts have reassessed the meaning of those revolts as they attempted to keep pace with the changing situation in Egypt and other countries whose political systems were transformed that dramatic winter the West calls a “spring.” I do not attempt here to offer a comprehensive account of the meanings of those events. Rather, I pick up on the lesson I learned from the man selling bobble-headed dogs in 2005, years before Tahrir, as a means by which to understand something about the changing cultural scene in Cairo, both as it undergirds and reflects the historical transformations of the past years and as a key building block of a reading strategy that puts circulation at the focal center. At the core of that anecdote, which I recorded during my first research trip to Egypt, is the disconnect between the origin of a manufactured object and the meaning it carries. Were the bobble-headed dogs American at all? I asked my Egyptian friends. I was missing the point, they responded. The vendor was using a cheap plastic toy made in China to make a point about the American export of democracy. The vendor was a sophisticated critic of globalization itself: the object itself might be made in China, but to Cairenes it both signified an American thing and neatly symbolized the interplay of American products (useless toys) and American ideologies (democracy for export). “You Egyptians must consume these things, adopt these ideas, because America tells you to!” And the joke was funny to my Egyptian friends, a satire they appreciated. No longer was the bobble-headed dog simply a silly toy intended to sit on a car’s dashboard. Now it signified something completely different.

This chapter takes an extended look at a more complex version of this situation, wherein cultural forms associated with the West in general and with the United States in particular—cyberpunk fiction, superhero comics, social networking software, and text-messaging language—make their way into the Egyptian cultural scene and are imbued with rich new sets of meanings. In Cairo, however, in the cases I take up, these forms no longer tell a joke about the West. Rather, they jump publics: they have new sets of meanings that adhere to and build on their authors’ use of them and now serve as fodder for a range of local meanings and new forms. There seem to be familiar elements in the new uses of these forms, but the American reader no longer comprehends them, just as I misunderstood the Cairene vendor even while I grasped his words. As a result, the message of these cases reveals the limits of American models of democracy as they are imagined in the West as exportable products. We are witnessing what the end of the American century looks like.

And yet, paradoxically perhaps, the first months of 2011 were a period in which American eyes and pens turned back on Cairo and revisited the narratives by which Orientalist tradition had previously translated a storied city. As Cairo was transformed in the revised American narrative—from ancient city to young metropolis—many American chroniclers found themselves identifying with a young Cairo, even when they least understood it.

* * *

In the wake of the Arab uprisings of 2010–2011, which in Egypt were especially widespread and dramatic, Western observers gave significant attention to the role of youth and their use of digitally enabled forms of social organization. Egyptian literary fiction had already been associated with the big political and historical questions, and many agreed with its major critic, Richard Jacquemond, when he called twentieth-century Egyptian novelists “the conscience of a nation.”

1 In the first decade of the current century, a new generation of Cairo-based writers—those publishing their debut novels in the 2000s—frequently employed innovative forms and linguistic experimentation drawn from a global cultural palette while exploring domestic or local social and political themes. Their work, because of how it seems to anticipate aspects of the uprisings, begs the question of whether and how the new Egyptian novel is democratic. It also offers a stark alternative to the patterns by which Western analysts understood and explained what was happening in Tahrir Square and elsewhere in the country. Democracy and narrative, whether Egyptian or Western, are intimately linked, of course, because the series of explanations that Western journalists and other alleged experts gave to translate the unfolding “Arab Spring” were ciphers for Western attitudes toward Egypt; these explanations also changed dramatically when the public they addressed rejected them—the Western narrative—for what was happening.

Discussions of democracy and the twenty-first-century Egyptian novel tend to replicate the categories by which we understand the novel in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, so such discussions have yet to account for significant changes in the context within which the Egyptian novel operates during the digital age. In her introduction to a special issue of

Journal of Postcolonial Writing dedicated to Egyptian literary modernity, for example, Caroline Rooney foregrounds the question of democracy. The issue went to press in the wake of the 2011 uprising, and in order to highlight the link Rooney, the issue’s editor, quotes the major Egyptian novelist Bahaa Taher (b. 1935), whom she asked in 2010 whether “we might think of literature as a form of democracy.” Taher replied emphatically: “Yes, of course. It not only promotes democracy, it

is democracy.”

2 Taher’s statement, in the context of his own previous novels, suggests that the dialogic qualities of the novel in general and the ways in which the Egyptian novel in particular weaves debates about the nation into its very fabric constitute the democracy of the genre.

3Something different is going on in the twenty-first-century novel. To be sure, younger Egyptian writers have addressed social and political questions in their work and in general are deeply conversant with their literary forerunners (including Taher). But the social and geopolitical context within which they work has altered so dramatically during the digital age that it should come as little surprise that their work has a markedly different relationship to democracy. Taher’s statement does not capture it.

4Part of the challenge is that we do not yet have a developed methodology for thinking about literary production within the context of globalization or the digital age. In

chapter 1, I argued that critics of the contemporary novel must attend to logics and contexts of circulation in order to address the changed episteme that has been ushered in by the massive economic and technological revolutions of the past four decades. Following discussions in sociocultural anthropology of the influential “cultures of circulation” argument by Benjamin Lee and Ed LiPuma, my contention is that the massively changed context within which the novel operates in the twenty-first century requires a different method of critical reading, one always localized to the particular framework of the work in question.

5 What this means in practice is that the global flow of cultural forms across national literatures—fueled by digital technologies that allow easy and rapid transport of literary texts and of visual and aural material—must be attended to without ignoring or occluding more local (i.e., national) contexts, literary traditions, and meanings. Critics should seek to achieve a balance of attention between moments of transnationally inspired cultural encounter and that which remains local and difficult to translate. Perhaps this balance will help us to avoid the pitfall of celebrating the “literature of globalization” in terms of diffusion, hybridity, appropriation, influence, or any other shorthand characterization that tends to be overly triumphant regarding globalization’s capacity to collapse local difference for its own economic purposes.

6What does attending to the transnational circulation of cultural forms mean for the recent Egyptian novel? And what does it mean for the question of democracy? Let me first back up before I argue for the particularity of the twenty-first-century Egyptian novel.

In the second half of the twentieth century, a distinguished body of Egyptian novels addressed contemporary Egyptians’ relationship to their history and the Egyptian nation’s failure to live up to its own potential. Naguib Mahfouz, Bahaa Taher, Sonallah Ibrahim, each with a dramatically different style, belong to this rich literature. It is fair to say that Egyptian novelists of this period were both richly aware of their own literary tradition and conversant with other national literary trends and forms. But during the 1990s, a younger generation of novelists turned away from such political concerns and apparently national questions and moved instead toward technical innovation. Samia Mehrez, a leading critic based in Cairo, links this shift to this generation’s awareness of “dismal reality, at both a personal and a national level, that prompts them to write what they want.”

7In the 2000s, as the long state of emergency under President Hosni Mubarak persisted and Egyptian society and politics seemed ever more stagnant, a still newer cohort of young writers and artists looked outward beyond the nation’s boundaries. The digital revolution brought a variety of cultural forms—including cyberpunk, graphic novels, and social networking—into the Egyptian cultural milieu and made access to a world outside Egypt immediate and more easily accessible than ever before. This access was evident formally, linguistically, and thematically in the work of several of these writers. In the second part of this chapter, I explore this point with respect to a specific case, but first I want to ask, Is the new Egyptian novel democratic?

In order to answer the question, we must first understand how fraught it is in Egypt even to ask it. “Democracy” and the “democratic” novel are two of the forms in circulation—part of what Arjun Appadurai called the “ideoscape,” a landscape marked by a transnational movement of ideas and ideologies, in his now classic account of the cultural aspects of globalization

8—that were accelerated with the neoliberal aspects of globalization. It is what everyone in the West wants of Egypt—to be democratic—and so we asked the question with the Arab uprisings of 2010 and 2011, and we asked it again in 2013 in the wake of the popular uprisings against President Mohammed Morsi and the military coup that ousted him. In late 2014 and early 2015, we are deeply pessimistic about the question, but we still ask it of the new Egyptian novel. Will you be—can you be—democratic? Foreign aid and military intervention depend on the answer.

In the wake of the so-called Arab Spring—which more accurately in the Egyptian case should be referred to as the #Jan25 movement (the Twitter hashtag antigovernment protesters used to coordinate communication)—many Western commentators attributed the speed and impact of the mobilization of young Egyptians to their use of U.S. technologies such as Twitter and Facebook. This attribution seemed a way of managing a more uncomfortable realization by Americans at the time: that the United States might increasingly be allied with antidemocratic forces in the Middle East, as its long support of Hosni Mubarak and his police state seemed to suggest.

If American innovation offered an antidote to U.S. financial and military support, the argument goes, the circulation of U.S. culture and cultural forms such as social networking media represented a “good” aspect of America in circulation. The putative democracy of Facebook and Twitter, both how they worked as spaces of open deliberation and through their alleged ability to topple a dictator, could stand for a “good” export of American-style democracy to the Middle East to counter the “bad” version exported via the Bush administration’s militarism under the guise of spreading democracy. Thus, it seems almost overdetermined that U.S. media venues covering the Egyptian protests of early 2011 paid particular attention to the role of these American technologies and forms. When a small item in

al Ahram about a young Egyptian man who named his newborn daughter “Facebook” quickly went viral across Western newspapers and websites, taking an unsigned one-inch article from the inside pages of a Cairo daily and broadcasting it to tens of millions of Americans, the celebration of Face-book reached absurd proportions.

9 Such accounts overemphasized the role of digital technologies and social networking in accounting for the Egyptian struggle for democracy.

10 They also borrowed from the now pervasive misreading of the global circulation of American cultural forms wherein social networking media constituted the new space of democratic deliberation.

So, returning to the question asked earlier, we can now identify a question to ask of the new Egyptian literature when it seems to employ or invoke American forms or be in dialogue with American literary genres, software, and popular culture and then apparently leaves behind or transcends its American referents. Without a renewed paradigm for considering such texts’ engagement of the outside form as more than derivative, we may miss what they show us: the ways in which creative Egyptian writers and cultural producers play with apparently legible American forms in circulation are in fact more subtle than a mere import and appropriation of outside forms. When young novelist Ahmed Alaidy invokes Chuck Palahniuk’s novel Fight Club (1996) as a source of inspiration, for example, and Magdy El Shafee names as his inspiration graphic novelist Joe Sacco, whose novel Palestine (1996) found a unique way to represent the noisy and crowded Cairo street, much more is going on than simple “diffusion” of two American authors’ creative work about democratic counterpublics. Circulation, contrary to one of its operative fictions, is not a two-way street, aller-retour, it turns out. There are many endpoints from which cultural forms do not return.

In the third section of this chapter, I focus on the comics of Magdy El Shafee (b. 1961), whose book

Metro (2008) is generally considered the first Egyptian graphic novel, to push the “ends of circulation” idea further with a reading of a particularly intriguing author. I extend the discussion in the fourth section to include remarks on the prose novelist and poet Ahmed Alaidy (b. 1974) and the creative nonfiction writer and dialect poet Omar Taher (b. 1974), and give an extended reading of Alaidy’s major novel in the fifth section. But several other writers from this generation can also be discussed in these terms, including Mansoura Ez Eldin (b. 1976), Ahmed Nagy (b. 1985), Muhammad Aladdin (b. 1979), Khalid Kassab (b. 1974), and Ghadah

ʿAbdel

ʿAl (b. 1978), author of the hugely popular blog

I Want to Get Married!11 What these writers’ work helps us to understand in various ways is how circulation is both a useful rubric for thinking about democracy in the twenty-first-century Egyptian novel and a problem. First, however, I want to take a more careful look at the American narrative of the Arab uprisings as it developed in real time.

NARRATING TAHRIR

By telling the story of the uprisings as a revolution produced by social media, American commentators were taking a stand in a debate that has been waged among scholars of global culture and that may help us to see the interplay of the global and the local with more nuance. Should cultural critics who are attentive to the rapid and transnational circulation of images, ideas, and public forms focus on the circulation itself—how it happens, what circulates, and so forth—or on the more local meanings that adhere to or emerge from or are hidden by these forms in motion?

12 By attending somehow to both, we can move beyond the limits of a strict postcolonial critique, which might focus on the ways in which Egyptian creativity appropriates that which comes from the imperial center as a form of resistance to neoliberalism, and beyond an approach focusing only on movement, which eliminates from cultural production its rich sets of meanings. Mainstream media accounts of the uprisings, for their part, focused more on the movement than on the local meaning. What was common in many such American accounts was that youth—a new generation—were enabled by the new media technologies to do something unexpected in the Middle East.

13 Looking for heroes in a revolution without them, these accounts zeroed in on Wael Ghonim, Google’s head of marketing for the Middle East and North Africa. In July 2010, Ghonim had created the important Face-book page “We Are All Khaled Said” to bring attention to the Egyptian police’s torture and killing of a young man from Alexandria; the page was seen as a key method of organizing the January 25 protests. (Months later, in the fall of 2011, American media would speculate that Ghonim was a likely choice for the Nobel Peace Prize.)

In detecting a pattern among many American accounts of the Egyptian protests and uprisings of late January and February 2011, I do not mean to suggest there was some collective decision by media moguls on how to tell the story. Rather, we can note how the narrative employed to explain a complex situation distant from American audiences shifted. There are two aspects to this claim: first, that there was a prevailing narrative and, second, that it shifted. Like any narrative, this one had to organize disparate information in the effort to explain a complex situation with many unfamiliar characters, histories, and settings to a distant audience not yet initiated into the plot or its details. Subtlety had to be left behind or out. As an explanatory device, though, a narrative may also be blind to information and interpretations that do not fit, or it might absorb them to better hide their challenge. And like other American narratives about foreign settings (especially about the Middle East), this one would reflect as much about American self-understanding as about Egypt. After all, the story must captivate its audience, and to maximize its reach it must orient itself around its audience’s interests, preconceptions, and desires. When there is a mismatch—when the narrative does not reach or captivate its public—it must change or shift.

As the narrative of the uprisings in Egypt shifted, it replaced a residual account of the contemporary Middle East that was notably different. During the previous decade, scholars such as Bernard Lewis and Fouad Ajami had professed an account of the Arab world that had become influential far beyond the academy and extended into the White House itself. With titles such as

What Went Wrong? (2003, Lewis) and

The Foreigner’s Gift (2006, Ajami), the new Orientalism of the 2000s looked much like the Oriental-ism of the twentieth century. Arabs were caught up in old grudges, mired in the past, unable to forget defeats either decades or centuries old. A new crop of native intellectuals and writers from Iran and the Arab world had emerged to craft what Ali Behdad and Juliet Williams call “neo-Orientalism”: “a mode of representation which, while indebted to classical Orientalism, engenders new tropes of othering.”

14The coverage of the first days of the protests in Egypt demonstrate how older “truths” from the Orientalist storyline about Egypt were repeated. As the Tunisian uprisings of December 2010 and January 2011 seemed to pass the baton to Egypt, where momentum grew quickly, U.S. media turned to journalistic “experts” for explanation. For example, on January 30, 2011,

Meet the Press featured a six-minute interview with Thomas Friedman, the

New York Times columnist and author whose book

From Beirut to Jerusalem (1989), winner of the National Book Award, established him as a Middle East expert in the eyes of many in the media. On the sixth day of massive protests in Cairo,

Meet the Press host David Gregory asked Friedman a simple question: “Is there any way that Mubarak can stay?” The way Friedman formulated his reply is revealing: “You know, I don’t want to make any predictions. That’s going to be determined by the Egyptian people. To me, what I think the United States should be focusing on are three things. One, emphasizing that we hope that whatever transition there is peaceful. Two, that we hope it will be built around consensual politics, not another dictatorship. Three, that whatever regime, whatever government emerges, whether it has the Muslim Brotherhood or not, it’s a government that is

dedicated to ushering Egypt into the twenty-first century” (emphasis added).

15Friedman would repeat this last phrase, “ushering Egypt into the twenty-first century,” later in the interview. But first he would give a more resonant image of Egyptian backwardness: “Egypt, and really most of the Arab world,

has been on vacation from history for the last 50 years, thanks largely to oil. Egypt didn’t have oil. It had the peace treaty with Israel. What peace with Israel was to Egypt, oil is to Saudi Arabia. It got Egypt all of this aid, it allowed the regime to move very slowly on democratization. And now it’s got to play rapid catch up” (emphasis added). Friedman here provided a startling image of Egypt on vacation from history and then attributed that absence, bizarrely enough, to oil. As if hearing himself, he noted that Egypt doesn’t have oil and then substituted a contradictory and completely enigmatic explanation for why Egypt is “on vacation from history,” one that turns out to be very historical: its 1979 peace treaty with Israel. Gregory never questioned him on this confusing explanation, so it stood as given. The Orientalist logic here is multiplied: out of history, in history, oil, Israel—it all blends together in Friedman’s statement.

I am using Friedman as shorthand for the narrative that would be supplanted. But because Friedman is already notorious (in many circles) for his sloppy forms of argumentation and is in any case a celebrity columnist with a sometimes idiosyncratic perspective, let me give an example from another media outlet:

ABC World News with Diane Sawyer. On January 25, 2011, the first day of the protests in Cairo, Sawyer turned to young correspondent Alex Marquardt, who was reporting on the “the latest violence to spread across the Arab world in the wake of the stunning overthrow of Tunisia’s president.” The key word here is

violence, and the idea that it was spreading across the Arab world is the main point. Marquardt continued: “Diane, today has been called a day of rage in Egypt, and it’s living up to the name.” The date January 25 was indeed called a day of rage for Egyptians, and yet the focus on emotions commanded the story. Because this is broadcast news, very few words were allowed to relate the account (about four hundred words, by my count), and so the emphasis on rage, violence, “chants,” “anger,” and so on undergirded previously given impressions of a chaotic Middle East. Now there are certainly sophisticated things one might say about the role of emotions or affects on politics.

16 But here they perpetuated older stereotypes of “the Orient” as a place of massive emotions, violence, and danger. The following day, again on

ABC World News, Sawyer focused her opening on what she called “a kind of chain reaction across the Middle East,” emphasizing that “the chaos could have serious repercussions right here in the United States.” In a clear attempt to make the distant story relevant to her domestic viewership, she asked correspondent Martha Raddatz “to tell us what those repercussions could be.”

A graphic filled the screen, asking in all caps: “Why is Egypt Important?” Instead of providing her own analysis, Raddatz instead channeled the official U.S. position: “Listen to the president today.” The screen cut to President Barack Obama saying, “You know, Egypt’s been an ally of ours on a lot of critical issues.” Back to Raddatz, who provided a shorthand elaboration of his statement: “Issues like the Mideast peace process and fighting terrorism.” There, in almost telegraphic phrases, were the key repercussions that apparently mattered to the American audience. Then, for further backup, Raddatz offered a quote from an expert: the camera cut to a white American man wearing business attire, sitting at a desk. The caption provided his name, David Bender, and position, the vague but professional-sounding “Analyst, Eurasia Group” (the Eurasia Group is a global political risk consulting firm, founded in 1998, whose motto is “Defining the Business of Politics”).

17 Bender then stated on camera: “If the Egyptian government falls, then, sort of, all bets are off throughout the region.” Anxiety, rage, instability. Then, by the logic of chain reaction that Sawyer led the news with, the 2:15 segment turned to Yemen. Raddatz’s voice grew increasingly worried: “The protests have even spread across the water, through the deserts, to Yemen.” And another graphic on the screen asked: “Why I s Yemen Important?” Raddatz provided more fear: “The list is long and frightening. A training ground for al-Qaeda. The home of Anwar Al-Awlaki, a terror leader more dangerous than Osama Bin Laden…. If the Yemeni government falls, no one will be there to challenge the terrorists.” ABC’s quick tour around the Middle East showed that the chain of protests against authoritarianism was ultimately to be seen as frightening. Raddatz, ABC’s senior foreign affairs correspondent, cast the revolution not as something in the American tradition of liberty from tyranny but rather as something with a likely negative impact for Americans: “So while protests may be cause for cheering in some places, in others these scenes should make Americans

very nervous.”

18These accounts stand for scores of similar accounts from those early days in late January, with American journalists repeating the “truths” perpetuated by the Washington political establishment: Mubarak was corrupt, perhaps, but the alternatives in Egypt (chaos, fitna, Islam) were worse. Reporters showed themselves in harm’s way. ABC’s Alex Marquardt, for example, showed himself after having been tear-gassed, his eyes watering while a bumpy camera ran down the street with him. They created fear on the American viewer’s TV or at least told the viewer to be fearful. Sensationalism ruled, and the official U.S. line—which Egyptians themselves were highly critical of—was literally parroted to American audiences via the media.

But then somewhat abruptly the story line changed. Within a week, the “chain reaction” of rage and chaos could be characterized in a new way: as youth driven, digital, and fun. A utopia in Tahrir Square. What changed, and why? In some ways, the collective shift in narrative about the Egyptian protests was market driven.

19 As Mubarak stayed on the stage in the largest city and largest country in the Middle East, the reporting by U.S. media thus far wasn’t sufficient for American audiences either in quantity or quality. Because of the way the Internet had affected how readers got their news, Americans had numerous options. Hungry for more news, they had encountered other interpretations of what was happening on Arab media.

Al Jazeera English (AJE)—a twenty-four-hour news broadcast channel that was long suppressed from U.S. cable and satellite platforms—offered streaming video of its coverage of Cairo. And it was good. (In August 2013, Al Jazeera Media launched Al Jazeera America, a separate channel with American programming that has since made inroads into U.S. markets, but in 2011 AJE was available almost exclusively via the Internet.) Although AJE has its own tendencies toward sensationalism, to be sure, its prevailing story line in this case was not fear that a flood of al-Qa

ʾida terrorists would be unleashed upon the United States should Mubarak fall but rather a historic struggle for freedom from the tyranny of regional dictators. U.S. viewership of AJE surged in a few days. (Reflecting back on their own coverage of the Arab Spring, American media outlets took a variety of positions on AJE’s coverage, but none ignored its major role.)

20 Eager to compete, U.S. media corporations sent their own reporters to Cairo. American audiences were evidently seeking a different account or were at least able to see that the prevailing one in the United States might have some holes in it. The new account embraced a logic of the digital revolution suited to the medium—which required it because AJE was viewable for most only via streaming video.

If the new message about Tahrir fit well with the medium, a story about Tahrir as a digital revolution was ready made for the Internet consumers of news. And the message did change starkly as CNN’s Anderson Cooper and a slew of other celebrity journalists, including Christiane Amanpour for ABC and Katie Couric for CBS, arrived in Cairo in their khaki foreign-correspondent shirts.

21 I point out these journalists’ attire because of the way it plays into the performance of foreign correspondence, itself a part of the entertainment factor of the news. Amanpour favors the khaki, which recalls old-time war correspondents from the Vietnam era. Cooper quickly gave up his vest for a more contemporary dark-hooded sweatshirt. Couric was seen wearing both khaki and the hooded sweatshirt.

On the print side, a second bureau of the

New York Times now competed with the first. Michael Slackman, veteran correspondent aided by young Lebanese assistant Nadim Audi, worked across town from newly arrived correspondent David Kirkpatrick, a generation younger than Slackman. The

Times had also hired Liam Stack, a Columbia graduate student who had taken a hiatus from graduate school to write for the

Christian Science Monitor, and he, like Audi, sometimes shared bylines with Slackman. Kirkpatrick, with no Middle East experience and little foreign reporting, challenged the veteran Slackman, who had years of experience in the region (and would eventually be sent home to become deputy foreign editor). The personalities were important to the coverage. Rivalry was barely hidden. Gender and sexuality were key. When CBS’s Lara Logan was sexually assaulted by a crowd on the very night that Hosni Mubarak stepped down, the vicious and deeply disturbing attack became a referendum on “true” Middle Eastern attitudes in the wake of the apparent democratic revolution (the story itself wasn’t reported for four days).

22 Scholars of the Middle East created their own websites to challenge the superficiality of mainstream media coverage, and the excellent website Jadaliyya emerged as a go-to source for those interested in more depth and has since become a staple of analysis of events in the Middle East.

Edward Said notes in

Culture and Imperialism that American attention to other parts of the world works in “spurts”: “The foreign policy elite has no long-standing tradition of direct rule overseas, so American attention works in spurts; great masses of rhetoric and huge resources are lavished somewhere (Vietnam, Libya, Iraq, Panama), followed by virtual silence.”

23 There is nothing, and then there is a barrage of information, almost overwhelming in its scope and intensity. Here was one of those spurts. Much good reporting was done, of course, particularly by those working for the

New York Times, the

Los Angeles Times, and sometimes the

New Yorker, where the long form allowed for more nuance, and the ease of access to publics meant that citizen journalists and anyone with a smart phone could upload their videos or break some news. To be sure, I have relied on the work of many of these journalists to understand what was happening. Ironically, the massiveness of the attention to the events in Tahrir allows us to discern a pattern, a narrative, more easily. No doubt there are exceptions, and some analysts did not fall into the new narrative trap. In general, however, the narrative told by Lewis and Ajami and repeated by Friedman in the coverage at the beginning of the uprisings—of a Middle East stuck in its own past—gave way now to a narrative about a Middle East in its “spring,” driven by a new generation of tech-savvy, Blackberry-carrying Tweeters. This was not your grandfather’s Middle Eastern revolution.

Can we step back to compare the old and the new narratives and ask what the blindnesses of the new narrative were? I cannot hope to be comprehensive, of course, and this is not a chapter about what happened during the Arab uprisings or about the series of disappointments that would follow in Egypt, leading to a return of the police state under General Abdel Fatah el-Sisi, who assumed the presidency of Egypt in June 2014. The role of religion was important but poorly understood, as would become clear in the next wave of media attention when Muslim Brotherhood leader Mohammed Morsi was elected to the presidency. There were excellent guides to the complex negotiation of religion within contemporary Cairo punctuated by new technologies and forces of globalization.

24 These types of insights and their subtlety were lost from the mainstream coverage, but for those readers interested in pursuing questions further, Jadaliyya offered extensive resources.

Thus far I have addressed the changing narrative about Egypt and the way American journalists and writers translated the foreign through the lens of the domestic. But rather than dedicate the remainder of this chapter to a deconstruction of Western discourse on the Arab Spring, I want to turn to contemporary Egyptian narratives, especially those from the decade leading up to that spring. Whether these narratives “predicted” the Arab uprisings—as some later claimed—or not, they help us to understand the tension between the local and the global that was elided or misunderstood in American accounts. Despite the focus on a youth revolution engaged with new technologies, a cohort of Egyptian writers whose work embraced precisely this juncture and were instrumental in creating a key Cairo counterpublic prior to the revolution has not been given due attention. A handful of academic readers of Middle Eastern literature and their students noted these writers, and a few of the writers were published in American periodicals and daily papers during the January–February 2011 spurt of attention, with at least one of them (Magdy El Shafee) securing a translation contract with a New York trade press (Metropolitan/Henry Holt) in the wake of that attention. But their work needs more extended attention for two reasons. First, appreciation of it helps us get beyond the easy formulation about circulation, technology, and Arab revolution that dominated the mainstream account. Second, their work shows how new American forms could enter Cairo’s cultural scene

without any sense that those who took them up were beholden to U.S. politics or “American values.” In other words, innovative works that might at first come into being via the presence of or engagement with American forms could lead eventually to texts in which American meanings are absent. They thus provide a vivid case of the process by which texts or forms in circulation jump publics—one of the many places where circulation ends.

CREATING CAIRENE COUNTERPUBLICS

In the Egypt of the past decade, if not longer, American forms in circulation became increasingly visible in the Cairene social and cultural landscape. Two apparently different American exports were especially prominent. First were the cultural products such as Hollywood and hip-hop, of course—which was nothing new, though now ever more ubiquitous—but also, increasingly, software, digital video games, and social networking sites. Second, there was an increasingly loud American discourse about democracy in the Middle East, whether the propaganda during the initial years of the U.S. occupation of Iraq (2003–2011), media and political commentary about the victories of the Hamas Party in the 2006 Palestinian parliamentary elections, or, closer to home, President Barack Obama’s speech in Cairo on June 4, 2009. Obama’s speech, titled “A New Beginning,” met with a mixed reception locally because of its apparent hypocrisy in the wake of the continued U.S. occupation of Iraq, firm support of Israel, and ongoing support for the Mubarak administration.

25 The increase in visibility and volume of these competing if complementary U.S. exports was due in part to the belated arrival of the digital age in the Egyptian capital and in the universities and urban centers of the rest of the country, which brought with it a flood of easily accessible Western cultural forms and discourse. But it was also due in part to the new pressures on Egypt in the wake of the events of 2001 and the so-called war on terror.

As the writer and dialect poet Omar Taher put it in

Shaklaha bazet (Looks like it’s falling apart, 2006), which established him as one of the leading voices of the new cohort of Egyptian writers and artists, a generation was born of this collision. In 2009, I was gathering literary texts by young Cairene authors to translate for a special portfolio to appear in a New York literary journal. As part of my research—inspired by the idea of a literary field, interested in the social and professional links between writers, and playing on the sociologist’s technique of snowballing—I asked prominent writers of the 2000s generation for recommendations on whom to include in the portfolio. I had started with Ahmed Alaidy, then thirty-five years old, whose novel

An Takun ʿAbbas al-ʿAbd (2003;

Being Abbas el Abd [2006]) had first caught my attention. The name “Omar Taher” kept coming up (no relation to Bahaa Taher), especially his manifesto-like introduction to

Looks Like It’s Falling Apart: “I am the son of the generation who got the shock of multimedia in my face after university. Attention was dispersed, all the world pressing upon me without mercy after years of deprivation, through the internet and satellite channels, and lay down on the floor in front of the power of the communication revolution, whose slogan was ‘the world is a village.’”

26Taher’s book of literary nonfiction named a condition—a new generation’s encounter with both national and global crises and their interplay—that suggested, or required, an appropriate literary style. Taher’s particular and noteworthy fusion of Egyptian dialect (

ʿammiyya) and standard Arabic (

fusha) and his invocation of comics as genre and cultural logic (as in his book

Kabitan Masr [Captain Egypt])

27 were born, according to the manifesto, from a generation’s experience of both geopolitics and digital technology. Taher collapses this experience nicely in the phrase “the world is a village,” with its layered suggestions of technological innovation and neoliberal political imperative (and echoing Hillary Clinton’s best-selling book

It Takes a Village, published in 1996 when she was First Lady). And he thereby shows the link in the dual logics of

circulation—which here means both the technologies of the digital age and the transnational ideoscape in which an empty slogan, “democracy for all,” becomes an American export.

I came to agree with his peers that Taher had named or depicted something crucial about his generation. In turn, his description of the way his generation grew up shows the link between a highly mediated youth and the literary evocation of a Cairene counterpublic no longer bound by national concerns—but not able to escape them fully either. First, his manifesto efficiently and accurately shows how global culture, including global politics, and local (Egyptian) culture and politics exist simultaneously in a layered palimpsest. Second, in the manifesto Taher summons up his own public both by invoking it (or calling it into being) and by grouping shared media experiences (and shared experiences of media) as productive of that public. In other words, the public that Taher names, invokes, and creates is a public in large part because its members have had similar experiences of the global mediascape.

In his manifesto, Taher repeats through anaphora a series of experiences shared by what he calls his generation (

al-jil or

al-gil in Egyptian pronunciation). “I am the son of the generation whose consciousness was opened by Mama Nagwa and Bo’louz, and with ‘Al-Sindbad’ Baba Magid Abdelrazaq and

Children’s Cinema with Mama Afaf Al-Halawi” (135). The manifesto begins with the shared television viewing of children of his generation, a series of programs so local, both generationally and nationally, as to defy translation. He moves through sequences of television programs, music, commercials, public-service announcements, and finally a barrage of global and local media events that converged in the young Egyptian consciousness: “I am the son of the generation that witnessed Egypt make it to the finals of the World Cup…. And we witnessed the rise and fall of stars beginning with Maradona going to Ali Hamida, and ending with Princess Diana” (135). Taher is doing more than rhapsodizing or waxing nostalgic for the cultural products of his youth. “Dear Reader,” he begins, “it’s possible that this book will not represent anything of importance to you, but it will mean a lot to you if you are one of the children of the generation” (135). This opening is the constitution of a public, which, as Michael Warner has argued, “requires preexisting forms and channels of circulation. It appears to be open to indefinite strangers, but in fact selects participants by criteria of shared social space (though not necessarily territorial space), habitus, topical concerns, intergeneric references, and circulating intelligible forms (including idiolects or speech genres).”

28 If Taher speaks to you, the opening declares, you are one of the generation; that is, you are a member of his public. If not, his words will not seem important. They will not address you; you are not part of his public.

Taher’s sequence of media events—and the pleasure of their juxtaposition in a catalog that feels Whitmanian via Allen Ginsberg—demonstrates something very much like an awareness that the public of his text is not endless and infinite but requires shared social spaces. But note that the public here does not require shared “territorial space,” as Warner notes, though it does rely on a common orientation toward the media-saturated spaces of Cairo. Thus, Taher gives us the precise time that certain programs of his youth aired (“And in the evening,

The World Is Singing and every night at exactly nine-thirty

Window to the World” [135]). Warner points out that publics are forms of poetic world making: “There is no speech or performance addressed to a public that does not try to specify in advance, in countless highly condensed ways, the lifeworld of its circulation.”

29 With great efficiency and with a literary voice that fuses the Egyptian dialect of Taher’s own

ʿammiyya poetry and a higher literary style, his manifesto specifies its own lifeworld.

It is appropriate, then, that although several of the events listed in Taher’s catalog are familiar to non-Egyptian audiences (or even to Egyptian audiences of different generations), most are highly local, which in turn allows us loosely to identify Taher’s public. Despite the sequence of global media events and outside cultural products that converge here, those same transnational flows of global culture

end here in Cairo. Yet that does not mean they are legible in full to an outsider. Indeed, when I finally met Taher and told him that I wanted to translate and publish his manifesto for the portfolio I was editing, he consented but told me it would be impossible to translate: no one outside Cairo would understand its references. I translated the essay nonetheless, annotated it heavily, and in the process killed the pleasure Taher’s designated public might take in it. My initial understanding of Taher’s “untranslatable” creative work was that he was addressing a counterpublic.

30 Now I think that the central point of Taher’s manifesto is that the dead end his generation had reached might in turn constitute a new Egyptian public if only it could recognize itself as such. The events of #Jan25 in Tahrir Square suggest what such a productive dead end might look like.

Understanding Taher’s work in this way has implications for the larger project of reading new Egyptian fiction as global and as engaging outside forms creatively. Older models of comparative literature that imagine Egyptian fiction and other national literatures as cut off from the world—or on the receiving end of literary influence—cannot hold sway from the perspective of the give and take of the digital age. When young Egyptian novelists take on Western cultural forms for local projects, as El Shafee does, it seems to me that the proper questions to ask are not about influence, cultural hybridity, or diffusion. Questions about the Egyptian novel can no longer be innocent of the interplay of the transnational circulation of abstract political ideas and ideologies (e.g., “democracy,” the “global village”) and global flows of literary and cultural production.

MAGDY EL SHAFEE’S CAIRENE COMICS

Indeed, such questions are not innocent, as the obsessions of mainstream American media indicate. When the journalist Robin Wright wrote a chapter on Egypt for her best-selling book

Rock the Casbah (2012), she decided to feature a profile of a young Egyptian woman many of us had not heard of before: Dalia Ziada.

31 Though Ziada’s name was not familiar, her story was. During the Arab uprisings, as U.S. journalists looked for ways to account for the massive organization of young Arabs and, most of all, for their effectiveness in ousting a president whom the same media had previously been telling its readers was permanent—the best option in a world marked by “extremism” and “corruption”—they grasped continually at examples of these American forms in circulation for evidence of what had changed. Most notable was the obsession with social networking sites such as Face-book and Twitter, as I have suggested. But Ziada was a particularly enticing case, for she had engaged in a surprising cultural act. As reported in the

Washington Post, in 2008 she translated into Arabic a fifty-year-old nonfiction comic book called

Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story. The original was published, with King’s agreement, in 1956 by the Fellowship of Reconciliation in the wake of the Montgomery bus boycott. According to an article on Ziada by Barbara Becker in the

Huffington Post, apparently channeling statements by the American Islamic Congress (the congress had funded the translation project), “With the aim of disseminating information about nonviolent protest to the semi-literate, the group [Fellowship of Reconciliation] decided upon the quick-to-grasp comic book format.”

32 Ziada translated the work, had it published, and with the help of the American Islamic Congress, according to Michael Cavna, “distributed thousands of Arabic-language issues…in the Middle East, including in Tahrir Square at the height of January’s revolution.” Cavna, the author of the

Washington Post article on Ziada and the comic book, was entranced by the link between the King comic as American document and its potential to influence the “hearts and minds” of young Arabs: “The book is testament not only to the power of King’s message…but also to the popularity of cartooning in the Arab world, especially among the younger generation. And [Ziada] is just one of many Arab comic publishers and cartoonists who believe passionately that their work can help inform, inflame and open the hearts and minds of their Mideast readers in the throes of revolution.”

33Wright accepted this version of Ziada’s story with little apparent additional research. As a result, the interpretive error Wright made was the assumption that Martin Luther King Jr. was an important inspiration for the Arab uprising and thus that the Arab uprising might be expected to follow a model with which Americans were familiar. At first blush, this assumption seems to extend an older tradition of American Orientalism in which Arabs’ struggle for independence and full citizenship was understood in terms of African Americans’ demands for equality in the United States. The African American press explored this possibility during the North African campaign (1942–1943) in World War II, and what I have called the ur-text of American Orientalism, the film

Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1942), hinted at it by allying the African American piano player Sam’s subjugated role with that of the Moroccan characters in the background.

34 Here, the role of the graphic adaptation suggests that the form itself—a comic book version of the Montgomery story—is particularly suited to an Egyptian audience. The link between what Becker referred to as the “semi-literate” audience of the 1956 original and the young generation of Egyptians was implied with a heavy hand. As such, Ziada’s is one of many such stories that Wright tells—about Arab hip-hop, Arab and Arab American stand-up comedy, Arab versions of

American Idol, and so on—in which U.S. cultural forms contribute to making a new Egypt, a new Arab world, crafted in an image with which the West can (and should, in her account) feel comfortable.

The story of the role of The Montgomery Story in the uprisings in Cairo, however, so far as I can tell, was greatly exaggerated. I do not question that Ziada translated the work or that the American Islamic Conference distributed it, but I do dispute that it had any substantial audience in Tahrir Square in 2011. Wright failed to inquire about the public of the Montgomery Story translation. Who comprised it? How many copies were out there? (Becker said that 2,500 copies were distributed from 2008 to 2011 throughout the Arab world, which is a mere trickle.) Given the somewhat straightforward images in the graphic adaptation of the story of the Montgomery bus boycott—it is notably not a robust version of the graphic novel, with straightforward panels heavy on prose—these seem fair questions, even crucial ones.

A hugely important graphic novel also published in Cairo in early 2008 was available to Wright but did not make it into

Rock the Casbah, nor did it register in mainstream media discussions prior to 2010.

35 Magdy El Shafee’s graphic novel

Metro would seem, on first look, to be a more sophisticated version of Ziada’s

Montgomery Story translation, one that might have been championed in some of the same Western media venues had it been read. But on closer inspection, it turns out to alter the very story Wright and others in the mainstream media were trying to tell: that the Arab uprising was in fact parallel to American models of democratic discourse. By extension,

Metro reframes our understanding of the relationship of democracy and the Arab uprising to the new Egyptian novel.

El Shafee’s work is important because in creating Egypt’s first graphic novel and emerging as the godfather of comics in Egypt, he seems to work in a familiar idiom. And yet to read his work closely, we must recognize that it and its engagement with the graphic novel jump publics, leaving behind the register familiar to Western readers. It is an example of the end of circulation from which an outside form cannot return to legibility. Metro cherishes its very locality.

First, where did El Shafee’s riveting work come from? He is the author of Egypt’s first graphic novel, so the genesis of his engagement with the form seems relevant. El Shafee has told me that his first influences as a comics artist were pharaonic drawings from ancient Egyptian tombs. But he has also spoken of his enjoyment of European comics such as

Tintin,

Asterix, and the work of Golo (Guy Nadeau [b. 1948], the French comic artist who illustrated for Egyptian newspapers in the mid-1970s). In an interview in March 2011, El Shafee remarked: “[Golo] is my

patron, as they say in French.”

36 Having encountered the work of the American comics guru Robert Crumb in the 1980s when he lived briefly in Paris while in his twenties, El Shafee returned to Cairo; through the 1990s, he worked in the pharmaceutical industry. In the “About Me” section of his personal website, he refers to his role at this time as “an evil Hippocrate [

sic] [who] rushes to tell the secret of his intimate colleagues [to] his dummy non-cultured BOSS in order to survive and gain more money. His job description: how clever he is in arousing a charming illusion to the public that drags more and more money from their pockets forgetting all about the right of every individual to get the RIGHT treatment.” Referring to this job and the hypocrisy it required, he writes: “I COULDN’T BEAR [IT]” (capitals in original).

37But then in 2001, in what El Shafee calls “the change” in his life, he participated in a comics workshop held in Cairo, the product of which was a collective volume. In 2003, he created the comic strip Yasmin & Amina, written with Waʾel Saad and published in the Egyptian weekly Alaa Eddin. That strip, which revolved around two girls who join their father secretly on board a commercial ship and so are plunged into global adventures, gained a local following. But the publication of Metro, a full-scale graphic novel, in 2008 was not only a personal accomplishment but also a signal event in literary Egypt. Metro was quickly banned, but El Shafee’s influence on a new generation of Egyptian graphic novelists and comic writers was substantial. (It has since appeared in translation in Italian and American editions.)

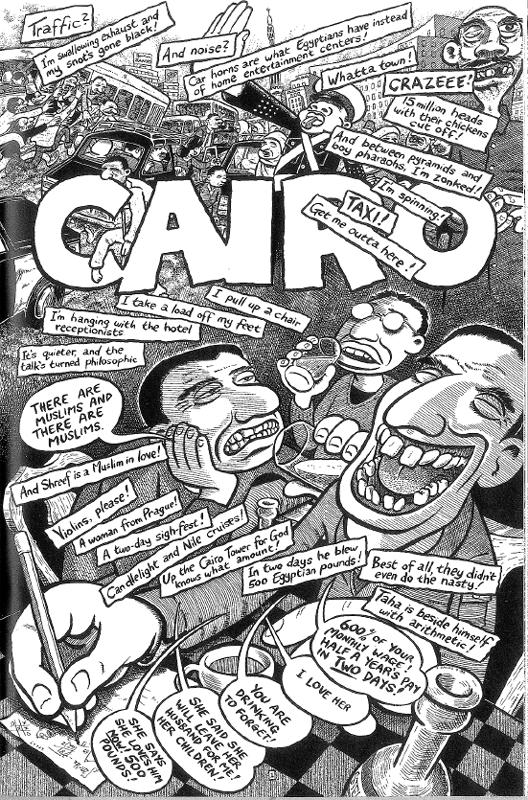

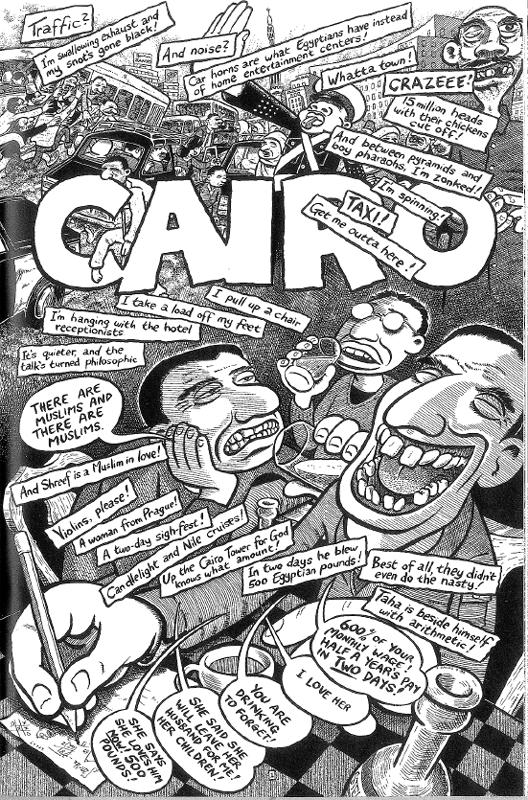

There are different ways to approach the question of circulation with respect to El Shafee’s work. The first seems initially something like literary influence. El Shafee rhapsodizes about the first page or two of Joe Sacco’s graphic novel

Palestine (1996), which begins with a frenetic page set in downtown Cairo.

38 Perhaps it took a foreigner to achieve this image, El Shafee says. “It was the first time I saw someone representing the

zahma of Cairo,” he told me shortly after the fall of Mubarak.

Zahma here means something more than traffic—a full blockage of not only the Cairene street but the entire social and political situation of Cairo.

39 So we have here the circulation of a formal element from Western comics: the crowded page, images spilling over the frame, with dialogue bubbles mixed and hard to sequence. Is this approach a way to connect what Robin Wright thought was happening in Ziada’s translation of

The Montgomery Story with El Shafee’s

Metro? If so, we would have to argue that Joe Sacco’s great Cairo page in

Palestine—a work written to contest the mainstream American media narrative about Palestinians (as Edward Said underlines in his introduction to Sacco’s novel)

40—offers a new way to represent the

hisa of Cairo (

figure 2.1). (

Hisa is a word that means more than noise; its closest translation into English denotes chaos, the frenetic, and noise all wrapped into one.) For El Shafee, such a formal element was not present in comics previously, whether in the work of Golo or in earlier European comics; he suggests it was a visual innovation within graphic fiction representing Egypt specifically. And as such, Sacco’s page allowed him to imagine a graphic form that might explode Cairo from the inside.

FIGURE 2.1 Joe Sacco’s graphic novel Palestine. (Image © Joe Sacco. Courtesy Fantagraphics Books)

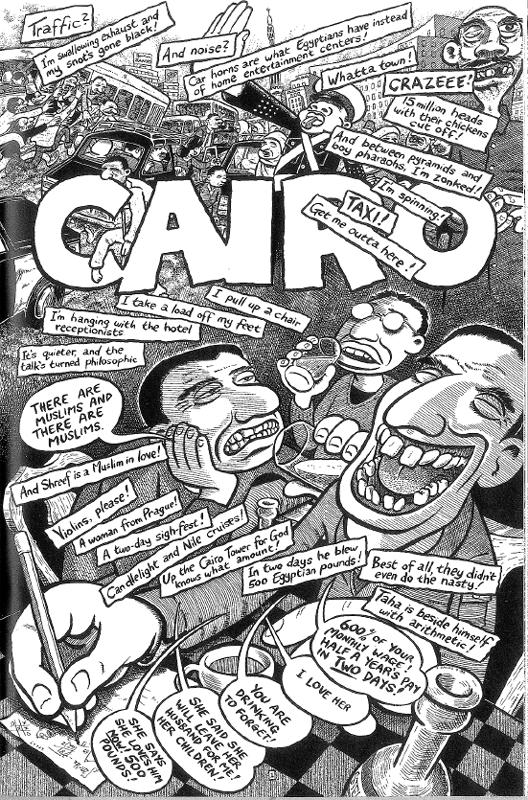

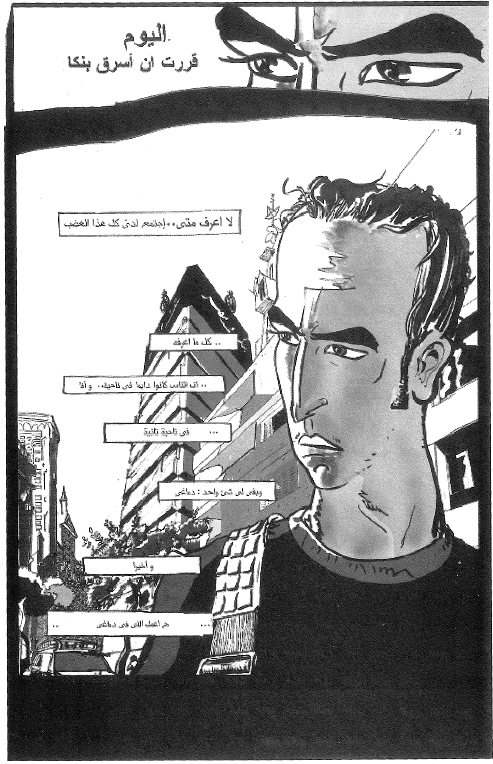

Sacco was not the only influence on El Shafee, or, rather, Sacco’s work was not the only outside cultural form that found its way into El Shafee’s representational repertoire. Sacco’s crowded page also allowed El Shafee to imagine graphic possibilities for representing the Cairene underworld as noir and linked with other works of both prose and graphic fiction that he was reading. Among the many interesting aspects of Metro are the formal borrowings from Sacco, the way in which El Shafee engages and extends the American superhero comic, and a strain of the dark neorealism of Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’s Watchmen series. There are hints, too, of Chuck Palahniuk’s punk novel Fight Club (1996), possibly filtered through Ahmed Alaidy’s deep engagement with Palahniuk in the novel Being Abbas el Abd. In Fight Club and in Alaidy’s novel, a doubling of protagonists is key to the narrative, where both reader and protagonist become confused as to who is directing the action. In Metro, characters are doubled, and there is some confusion of identities, but the Palahniuk strain is yet more viral via El Shafee’s representation of an underworld where street battles (between neighborhood criminals, corrupt politicians, and businesspeople) operate below the registers of the visible. Before I move to an alternate reading of Metro, one that counters an approach I associate with models of diffusion and influence, let me back up to describe the work.

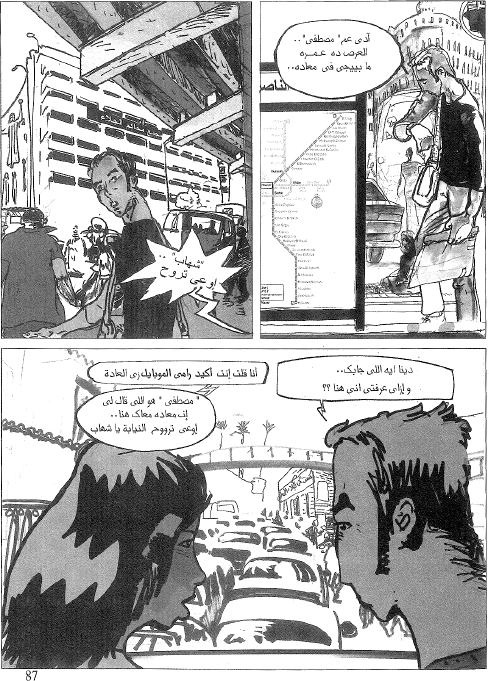

Metro tells the story of Shehab, a software designer and expert in the digital realm who is trapped within Cairo networks that will allow him neither to thrive nor even to live in safety (

figure 2.2). A way out presents itself via a wealthy neighbor who offers to finance Shehab’s idea for a software project, but the neighbor is murdered because of his involvement with a group of corrupt professionals. Shehab witnesses the murder and is at the dying man’s side when the man passes on a confusing message that seems to be the clue to the network’s treachery. With his friend Dina, an investigative journalist, Shehab aspires to expose the crime, which is being pinned on the wrong person to cover up the dangerous knowledge that the murdered man held. Following his best instincts, Shehab seeks to find a way to deliver “the truth” to some authority above or outside the corruption who might help to expose it. But he knows, too, that there is nothing outside the criminal circles of contemporary Cairo, which go all the way to the top, and so he looks for another way out of the cage. Here, his knowledge of the digital is of some help: he knows how to hack the system as he runs afoul of corrupt Cairo. He can make public phones in the Metro ring to communicate with his friend Mustafa; he can hack into the dead man’s cell phone to find clues to his mysterious dying words; and he can transfer funds to his own account by hacking into a bank’s secure network. This is not Bahaa Taher’s Cairo.

FIGURE 2.2 Shehab in Magdy El Shafees graphic novel Metro. (© Malamih Books. Courtesy Magdy El Shafee)

But what I have recounted is merely the plot of

Metro, not what it is

about. Alan Moore’s great guide

Writing for Comics (an inspiration to Alaidy and apparently to El Shafee), distinguishes between a comic book’s plot and what it is

about: “The idea is what the story is about; not the plot of the story, or the unfolding of events within that story, but what that story is essentially

about.”

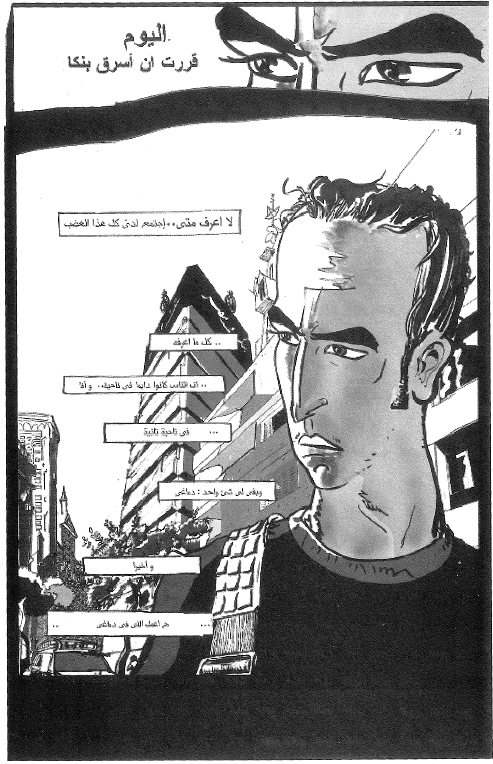

41 For Moore, the distinction is particularly important for comics art because of the particular fusion of frame transitions, image, and text. In this sense,

Metro is about the cage of Cairo and the impossibility of escaping it, whether it is composed of corrupt businessmen or the thugs who beat street protestors chanting for their rights. Foreshadowing the #Jan25 movement of 2011, El Shafee represents the Kefaya movement of 2004–2005, an important protest movement (the word

kefaya means “enough!” in Egyptian Arabic) that was often overlooked in many mainstream accounts of the Arab Spring.

42Metro is, of course, an underground story, and, like the underground train system for which it is named, the novel is concerned with networks of communication, transportation, and circulation, all of which lead nowhere except to political and social stasis. Maps of the Cairo metro permeate the narrative, and like most urban metros, the lines eventually come to an end (

figure 2.3). Shehab tells Dina: “We’re all in a cage. The way is wide open, but we’re stuck inside because no one ever tries walking out of it.”

43 Reflecting the

zahma, or blockages, of Cairo,

Metro’s pages are punctuated by propagandistic signs and sayings by Hosni Mubarak—a banner inscribed “For a better tomorrow: Mubarak” hangs over a street (42); pro-government thugs chant, “Long live our leaders! Long live our democracy! Enemies of the state go home” (66)—and represent protesters from the Kefaya movement and their chants: “No justice on the street! Nothing for the poor to eat!” and “Why turn on the victim? Why not the oppressor?” (67). In this sense of what

Metro is about, the graphics advance its meaning more surely than do plot or text. Its noir look and multiple graphic styles (including El Shafee’s incorporation of two pages by a comics colleague from Cairo, Muhammad Sayyid Tawfiq) are animated by fight sequences that combine superhero comics, the

Watchmen, kung fu, and

parkour.

FIGURE 2.3 Shehab and Dina in Magdy El Shafee’s Metro. (© Malamih Books. Courtesy Magdy El Shafee)

In

Understanding Comics, his now classic guide to reading graphic fiction, Scott McCloud catalogs the different kinds of movement between frames that are available to the comics author. It is in “the gutter,” or the space between frames, McCloud writes, that the comic book distinguishes itself as a particular art form: “Despite its unceremonious title, the gutter plays host to much of the magic and mystery that are at the very heart of comics.”

44 McCloud differentiates Western from Eastern techniques for comics transitions and argues that Western comics tend toward forward narrative progress in such transitions, whereas

manga and other Asian comics have a notably higher percentage of atmospheric frames in which multiple aspects of a scene, landscape, or character are shown. Forward progress is in such frames stalled; pacing is slower. McCloud offers statistical evidence for this assertion, but my critical impulse is to resist this binarism, which is redolent of Orientalist tropes about Eastern stasis and Western “progress.” In any case, given the global popularity of both

manga and American superhero comics, McCloud’s strict division of East and West may not hold true anymore (if his original analysis was correct in the first place) for the

readers of comics. The atmospheric frame transition may be characteristic of

manga, but it is hardly unfamiliar to the Western reader. Nonetheless, McCloud’s larger point about the effects of these different transition styles is useful.

In

Metro, whether El Shafee attributes the two types of frame transition to “Eastern” and “Western” styles or not, he clearly plays on both techniques. The novel reads at first as noir and quickly builds plot and narrative momentum. But then it slows down its narrative drive and lingers in the Metro itself, building atmosphere, depicting street fights that spill over the pages’ frames, and employing a consistently changing graphic style. None of this is impossible within what McCloud attributes to comics from the West, of course, and film noir in American cinema is well known for its atmospheric shots. Nonetheless, it is in these atmospheric, static frames, gutters, and transitions that El Shafee tends to leave his American reader behind—or, rather, where he seems to be less concerned with his international, non-Egyptian public. It is in these frames that he addresses his Cairene public in particular: that public knows the local referents of particular places and situations, and these localized frames do not resonate for the outsider. In other words, the crowded page of Joe Sacco’s Cairo cedes to a Cairene cage that is poetic world making for a different public.

El Shafee’s work jumps publics, and rather than stand as an example of the diffusion of the Western form, it takes aspects of that form, combines them with Egyptian literary traditions (the social protest novel, the nationalist novel, and so on), and summons up its own local public. In this way, it is similar to Omar Taher’s manifesto and to Alaidy’s fiction. It is new in Egyptian fiction, but it is not derivative or the simple diffusion of a Western form. The disjuncture in it pushes us to ask questions about the democratic aspects of the new Egyptian novel but also more generally to argue that critics of Egyptian fiction, among others, need to take seriously younger Egyptian writers’ engagement with both their own literary traditions and Western literary and cultural forms.

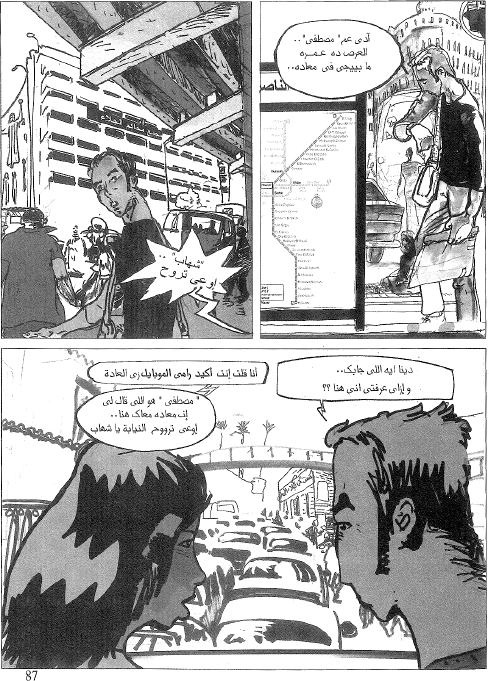

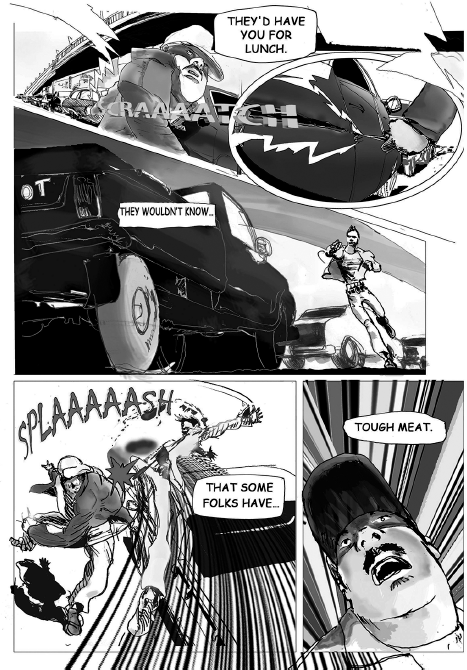

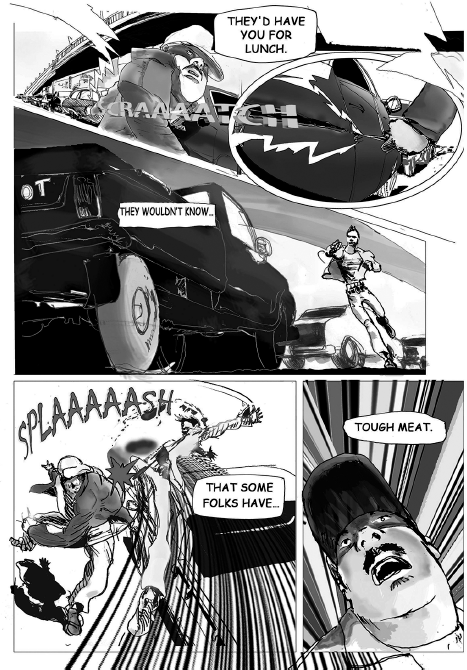

Because I have placed a heavy burden on the idea of jumping publics, let me offer a brief discussion of a short work in which El Shafee, here collaborating with Alaidy, plays with the very idea of “jumping.” In 2009, as I edited the Cairo portfolio, I wanted to include an excerpt from Metro, and I approached El Shafee for his permission. My editor in New York was resistant to novel excerpts in general, which are harder for the reader with no access to the complete work to comprehend. El Shafee had a solution. He had, he told me, already plotted a short work of graphic fiction with Ahmed Alaidy, estimated at six pages, and accepted my offer to translate and publish the shorter work. Titled “The Parkour War,” the six-page comic extends some of Metro’s concerns in brief and with new characters. Again, it is about a Cairo in which state corruption is generalized to the local, daily level.

The opening page sets the scene with an atmospheric drawing of an apartment building in a nondescript, lower-middle-class Cairo neighborhood. On the second page, a fat man is depicted coming to collect bribes from local shopkeepers—for their protection, one assumes. The text reads: “Like any filthy morning, people feeding off of other people…. Pulling the life right out of you…. They smell…like ashes.” But the corrupt man encounters a slim man, standing in a doorway, who decides to fight back. “They wouldn’t know…that some folks have…tough meat” (ellipses in original).

45 Over three pages, drawn with superhero-like colors and swooshes of combat and with sound effects such as “

SCRAAAATCH” and “

SPLAAAAASH,” the slim man fights the fat man and brutally beats him (

figure 2.4). In the final frame of the penultimate page, the slim man wins the fight by decapitating the fat man, whose head rolls to the ground.

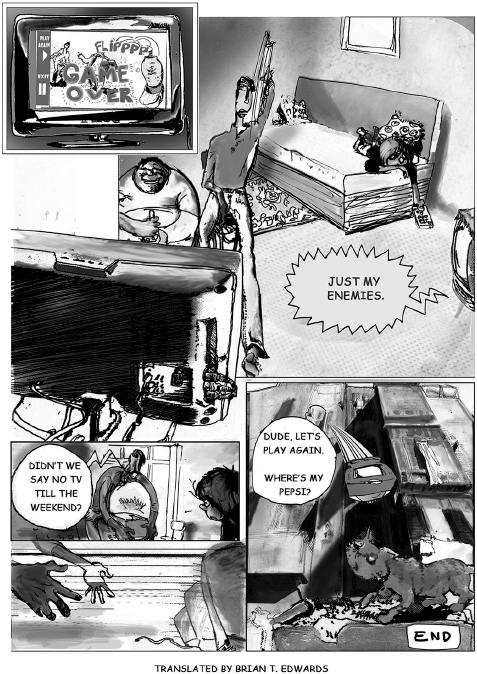

Commencing in the last frame of the penultimate page, however, a dialogue bubble interrupts the action. The line in the bubble wraps from the penultimate page to the first frame of the last page; in other words, it starts on the fifth page of the comic and concludes on the sixth page. In the original Egyptian Arabic, the line derives from a then recent Egyptian film called

El Gezira (The island, Sherif

ʿArafa, 2007), about a community of Upper Egyptians living with their own rules; the line would be familiar to many Egyptians at the time. I come back to it in a moment, but first let me remark that the final page has a surprise in it. The battle that we have been witnessing between the fat man and the slim man, it now becomes clear, was not a street battle at all, but rather a battle in a video game (

figure 2.5). And the elusive title of the short comic, “The Parkour War,” seems in retrospect to be the name of a video game that two young men in their teens, one fat and one slim, are playing on a PlayStation in a small apartment. Next to them, a child perhaps ten years old is watching a movie on a second TV set, dangling a remote, weary from watching too much television. The slim man, who has lost the game, throws the television being watched by the child out the window. “Didn’t we say no TV till the weekend?” he shouts. Perhaps he is the older brother of the child. He addresses his friend again: “Dude, let’s play again. Where’s my Pepsi?”

There is a lot going on in a short amount of space. On the first level, the heroic story of battling and defeating corruption cedes to a critique of young Egyptians stuck in their apartments, consuming media from televisions and video game consoles. On the one hand, El Shafee seems to suggest that these technologies are social soporifics, stamping out the political potential of Cairene youth. The boys stay in their apartment, playing video games as they suck down Pepsis. What the French ruefully called America’s “Coca-Colonization” in the 1950s is here present in its digital form: the PlayStation games of the 2000s are like the Coca-Colas and Pepsis of another era (and Pepsi is still present as an addictive, foreign commodity). But

parkour — that urban sport wherein athletic young people learn to scale walls, jump fences, and leap from rooftops—offers another possibility, one that competes against the easier and we might say older generational lament over cultural imperialism and political apathy. The flight of

parkour, which here is structured into a video game that we (as readers) do not realize the boys are playing, with Cairene referents difficult to translate, reveals a break. (El Shafee told me that he had joined

parkour clubs in Cairo, and here he brings it into his fiction.) That dual strand of circulation—the one easy to read, the other more elusive—suggests the double valence of an Egyptian fiction of the digital age.

FIGURE 2.4 Scene from Magdy El Shafee and Ahmed Alaidy’s graphic story “The Parkour War.” (Courtesy Magdy El Shafee and A Public Space)

FIGURE 2.5 The final frame in Magdy El Shafee and Ahmed Alaidy’s graphic story “The Parkour War.” (Courtesy Magdy El Shafee and A Public Space)

In my attempt to translate El Shafee and Alaidy’s comic into English without reducing it to a translatable value or a bit of exotica from Egypt, I encountered many challenges.

46 The Egyptian Arabic used is especially colloquial and employs phrases that barely translate when rendered into English except as phrases indicating violence and resistance (for example, “They’d have you for lunch. They wouldn’t know…that some folks have…tough meat” works well enough in English but loses the immediacy of the original). Egyptian argot was one thing, but the line of dialogue from the Egyptian film

El Gezira posed yet another problem. This short comic was clearly invested in exploring various forms of media in circulation in Cairo, so it is worth some further consideration of the problem posed by the line that wraps from the penultimate page to the final page. Here, the line from the Egyptian film being rebroadcast on TV references national culture, even if Egyptian cinema had and continues to have a transnational reach, at least in the greater Arab world. The line itself signifies a breakdown of the system: “From today there is no government. / I am the government” is a literal translation of the line as El Shafee has it in his original. But the TV set that the younger sibling watches competes against the TV on which the older boys play their video game (note the different styles of console and the multiple digital inputs on the older boys’ set). How to translate the line from the film? When we discussed it, El Shafee argued that comics should be clear and apparent on the first reading, and thus the Egyptian dialogue must be changed for an American audience. After offering a number of alternatives and some deliberation, I proposed a line from

The Godfather Part II: “I don’t feel I have to wipe everybody out, Tom…. Just my enemies.” El Shafee was enthusiastic and gave his full consent.

In using this line as a translation, had we made “The Parkour War” a translatable value to be carried along with the global flow of discourse from Egypt back to the United States? Or had we done some disservice to the very idea of jumping publics that I have argued is central to the theme of “The Parkour War” and at the heart of the genius of

Metro? Although I cannot claim that this substitution of a line from

The Godfather Part II was the best solution to the translation problem posed by the text, I want to end my discussion of “The Parkour War” by suggesting that the work still resists translation and has not become fungible and that it has not even really jumped publics back to the United States via this new line of dialogue. Like Omar Taher’s manifesto in

Looks Like It’s Falling Apart, El Shafee and Alaidy’s comic is ultimately impossible to translate in the sense that the public it addresses is one that uniquely comprehends both the national or local Egyptian

and the transnational references and referents. That comprehension is so deeply inscribed in the text that it cannot be loosened even with a line of dialogue from Francis Ford Coppola. Indeed, one can imagine a line from

The Godfather in the Egyptian novel or comic quite naturally as an element of global culture, but it is much harder, if not impossible, to imagine a line from Egyptian cinema or an Egyptian comic moving as naturally in the other direction.

PUBLICS AND COUNTERPUBLICS: ALAA AL ASWANY AND AHMED ALAIDY

If the Internet, digital downloading, and satellite technologies made access to a world outside of Egypt immediate and more easily accessible to Egyptians than ever before, the effects of this access are seen formally, linguistically, and thematically in the work of several of the writers of the 2000s generation. And yet, as I argue, these effects were the endpoints of global circulation: these writers’ engagement with the foreign—the global—was visible to Egyptian audiences and indeed figured in some of the most ambitious works, but it was difficult to circulate back to the West. When those works did circulate back to the West—say, in a classroom or through an individual American reader’s interest—the disconnect was such that the works did not register as interesting or innovative or even “Egyptian” enough. They seemed merely derivative, or they confirmed the erroneous position that democracy and technological innovation begin in the West and find their acolytes and imitators in an otherwise chaotic East.

The staggering popularity of Alaa Al Aswany (b. 1957), a writer first published by the intrepid Cairo publishing house Dar Merit, in the United States would be the exception that proves the rule. Dar Merit was run by Mohamed Hashem, who had been a key member of the Kefaya movement earlier in the 2000s (in particular its Writers and Artists for Change group) and through that decade had published daring fiction—and to a lesser extent poetry and nonfiction—out of a small office near Tahrir Square.

47 In the back room, evening gatherings brought together intellectuals, writers, and filmmakers. For Al Aswany, launched by Dar Merit, Hashem’s operation was apparently not going to reach a broad enough public; circulation mattered to Al Aswany. His novel

The Yacoubian Building, first published by Merit as

ʿImarat Yaʾqubian in 2002 but then reprinted by bigger Cairo publishers Maktabat Madbuli and later Dar al-Shuruq, quickly became the best-selling Arabic-language novel in the world.

48 With a film, a TV miniseries, and then a major U.S. launch for the translation of his novel in 2007, Al Aswany became the Arab author, aside from the late Nobelist Naguib Mahfouz, whom Americans had heard of if they had heard of any Arab novelists. The 2008 edition of Al Aswany’s second novel

Chicago, published in the United States by Harper Perennial, garnered a full publicity campaign; the

New York Times Magazine had Indian novelist Pankaj Mishra write a full profile of Al Aswany.

49 (I am not aware of another translation from Arabic to garner such resources.) Despite the greater publicity and as entertaining as it is, Al Aswany’s first novel does not capture the fusion of national critique and global cosmopolitanism that characterizes El Shafee’s or Omar Taher’s work in terms of either content (there are no digital hackers here) or especially literary form.

Scholars of Arabic-language literature debate whether

The Yacoubian Building is innovative, “serious,” and interesting from the standpoint of its language and technical craft or merely commercial, but most take the latter position. A literary soap opera with multiple intersecting story lines focusing on a corrupt business magnate, the gay neighbor, and a terrorist, it certainly has aspects of the melodramatic television serials that are popular in Egypt. But serious scholars of the Arab novel—such as Marilyn Booth, Richard Jacquemond, and Samia Mehrez—have encouraged readers, implicitly or explicitly even if sometimes a bit reluctantly, to take

The Yacoubian Building seriously as a document of the changing market for popular fiction.

50 Mehrez calls Al Aswany’s success “mind-boggling and overwhelming” and points to the Egyptian literary establishment’s contrasting perception that he is the author of “scandal literature.”

51For my purposes, though, what is important is how this novel’s depiction of the grand sweep of contemporary Cairo, realist and melodramatic, assured its circulation in U.S. markets. American publishing circles treated Al Aswany like a new Mahfouz. The front cover of the paperback edition features a quote from the highbrow

New York Review of Books: “Captivating and controversial—an amazing glimpse of modern Egyptian society and culture.” The