Screening of Leïla Kilani film ʿAla hafa/Sur la planche [On the edge] at the 7ème Art in Rabat, November 2012. The look of the film is tight, dark, oppressive—more than anything it captures and creates the sense of enclosure in a life, in a class, in misery. To me, the look is a form in circulation, and the format is familiar (starting with the end, then an extended flashback)…. But the language takes it off the circulatory path. It’s in [Moroccan] darija of course but filled with slang, Tanjawi [Tangier] dialect, language of the street. Sadik told me he was often reading the French subtitles to understand. The character Badia speaks so fast…. I found it compelling. Others apparently did too: it won the grand prize at the National Film Festival and is featured in this month’s Cinemag. But the audience at 7ème Art seemed not to agree. Maybe twenty to twenty-five people were at the screening—so dark, hard to say—in groups of two to five. Three different cell phone conversations took place during the film; not short ones either, with no effort to whisper—in one case the guy kept raising his voice to be heard over the film. People complained the first time but then just waited. And when the film was over, a young man shouted, “Jabouna an-nassu”: “They brought us here to sleep.”

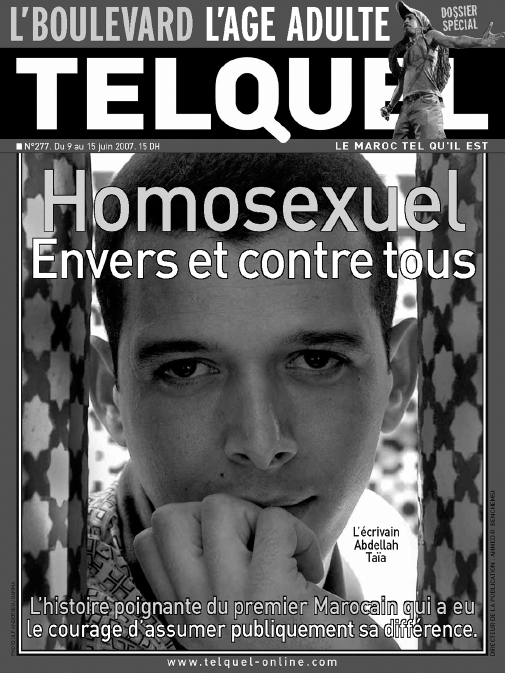

IN THE LAST WEEKS OF 2012, a new film sparked a vibrant public debate in Morocco—certainly not the first time a movie had commanded such attention and surely not the last in this dynamic nation of 30 million people. The discussion was reminiscent of other similar disputes from the past decade: the debate over Laïla Marrakchi’s film

Marock in 2006, the public coming out of novelist Abdellah Taïa in the same year, the airing on YouTube of a video of an alleged “gay wedding” at a private home in Ksar el Kebir in November 2007, and the open picnicking of a group of activists during Ramadan in 2009.

1 In all these cases, sides were drawn between those defending putatively traditional values and those who—their opponents suggested—had been seduced by foreign corrupting forces and who were now introducing those “foreign” elements into Morocco. This time the debate was provoked by a film by Lahcen Zinoun, a director in his late sixties better known as a dancer and choreographer. The film,

Mawchouma (translated for the Francophone market as

Femme écrite [A written woman]), was showing in selected cinemas in Morocco’s major cities. The problem was basically that Zinoun included shots of a naked woman.

At first blush, the controversy seemed ready made for a cultural critic trying to understand and explain the latest incarnation of social attitudes about gender, sexuality, and Moroccan identity in the early twenty-first century as well as the ways in which the transnational flows of images and ideas about modesty and the body from East and West come together in a land long considered a crossroads. Focusing on conflicts in the realm of cultural production has long been a preferred approach to untangling sociocultural complexity and one I have leveraged earlier in this book.

2 Indeed, in November and December 2012, I was trying to finish my research from the previous summer when I had gathered a substantial amount of material on young Casablancan authors and artists, around whom I had planned to write this chapter. But I sensed that I needed an anchor on which to build the chapter, and I considered whether the debate over

Mawchouma would work. I stopped by Mohammed V University and gave the talk that led to the discussion about

Innocence of Muslims I describe in

chapter 1.

As I began to follow the controversy around Zinoun’s film, I decided that the more interesting story—the more important critical angle—was elsewhere, heated as the discussion was. After all, the positions taken in the debate about Mawchouma were somewhat predictable, from those who championed the director’s artistry and his right to express himself to those who thought he had offended Moroccan and Muslim values with “pornographic” themes. All interesting and revealing but not surprising.

Further, as is often the case in Morocco, the most extended discussion of Zinoun’s film was limited to the cultural and financial capital Casablanca and to a lesser extent the political capital Rabat in large part because almost all Moroccan publishing and media are centered in the Casa–Rabat metropolitan area. Within that space, the debate was restricted to a particularly small subset of those who pay attention to contemporary culture and contribute to the discussion of it. I don’t mean to say that no one elsewhere in Morocco was aware of the controversy, but it was not something that people were debating or discussing in the cafés and classrooms in Fes, from which I had just traveled, or in Marrakech, where the film had not been included among the Moroccan selections at the annual Festival International du Film de Marrakech.

Mawchouma was showing in only one cinema in the country at that moment and only briefly.

A real conversation, however, was taking place online, especially on social networking media such as Facebook. There both fans and artists involved in the film itself debated, criticized, and defended the director, the actress, and so on in a way that I had seen before among Moroccan users of Facebook. Despite the large gathering of film enthusiasts present in Marrakech, it was online that the discussion took place. The film festival in Marrakech was strictly controlled in terms of schedule and audience, rendering what should have been a great public event in Morocco’s second-largest city into a private affair.

In other words, what was more interesting than the particulars of the discussion about this particular film was Moroccans’ ability to have the discussion and the means of access to that discussion, both of which had changed notably with the massive arrival of social networking software in Morocco. Access to the Internet itself has a history in Morocco, of course, and implicates class and gender differently from how it does in the United States. Since the late 1990s, cybercafés have been ubiquitous in Morocco and widely used. When they arrived on the scene, they were soon socially acceptable places for young Moroccan women to patronize and use, in notable contrast to cafés (i.e., shops serving coffee and tea) and cinemas, except perhaps in the more privileged neighborhoods of Casablanca and Rabat. By the early 2000s, Internet access was inexpensive, even for children of the lower middle class (sometimes even free during late-night hours). Although the rapidly improving level of access to the Internet was also changing in Egypt and Iran, all three countries are particular in the way and manner that their young people access the Internet—when, where, how—which leads in part to the particularities and real differences in how Moroccans and Egyptians used the same social networking software. Young Moroccans I spoke to about Egyptian use of social media were mystified that Egyptians liked Twitter and claimed that Moroccans were much more interested in Facebook. They had theories about why this was so (for instance, they emphasized Moroccan notions of community, which Facebook seems to emphasize more than Twitter). Also, cybercafés have never seemed as prevalent in Egyptian cities as they are in Moroccan cities. The increasing presence of smart phones in the second decade of the 2000s may obviate the need for the cybercafé. Either way, we must not forget the first decade of access to this software in Morocco. (Smart phones are still expensive in Morocco at the time this book goes to press, and many Moroccans, especially those of the lower-middle, working, and lower classes, use cell phones for texting and speaking to friends but go to computer screens to access the Internet and Facebook.)

One need not restrict the issue of Internet access and use to North Africa. In the United States, public and semiprivate discussions about literature and film are arguably more democratic because of social networking. Media scholars have argued that the ability to interact with and comment on works of literature, television, and film has made creators and innovators out of consumers of culture. Alex Galloway, one of the most innovative of such theorists, has drawn our attention to what he calls the “interface effect” and pointed to a striking rearrangement of how individuals engage not only with technology but also with each other.

3Can the same be said of Moroccans? Do the insights derived from observing American users of new digital technologies apply in such a different socioeconomic and political context? What does the use of social networking media in Morocco mean when we juxtapose it against low literacy rates in the country, and what do the energies to be found in such discussions mean when we compare them to low cinema-going and book-buying rates in Morocco? Does the way that Moroccans engage in such debates help answer the question that many were asking in late 2012 and still ask as this book goes to press: Why had the so-called Arab Spring bypassed Morocco?

It is tempting to pursue such questions. In the years since September 11, 2001, and with renewed energy in the wake of the Arab uprisings a decade later, many have been looking not only for predictions about the future of places such as Morocco but also for a more rigorous attention to youth culture in the region. The sense that the world is transforming around us because of the rapid changes in technology and related software that connect individuals allows for a fresh look at a region that for too long has been assumed to be outside of the forward progress of time. Morocco has undergone important social changes in the past decade or two as a result of a combination of transformations from within and the impact of events and developments from without. From the transition to the rule of young King Mohammed VI (known locally by the hip moniker “M6,” with the number pronounced in French) in 1999 after nearly four decades of reign by his father, King Hassan II, to the arrival and massive acceptance of digital technologies across the country, the past decade and a half have apparently ushered in a new Morocco.

4Americans should not assume, though, that greater access to public dialogue through digital technologies and a younger monarch taking the reins of the kingdom necessarily have led to a Morocco in which Western values or a pro-American position is ascendant. During much of the same period, U.S. policies have been especially unpopular in Morocco and, from many Moroccans’ perspective, have fractured a historic friendship on all but the official level. During George W. Bush’s administration, the global crackdown on terrorist networks had a powerful effect on Morocco as the kingdom partnered with the United States, frequently using the premise of routing out terrorists to settle domestic political scores. The U.S. military invasion of Iraq was criticized in Morocco, as it was elsewhere in the Arab world, even though many Moroccans considered Saddam Hussein to be a murderous despot. Arab and Muslim solidarity with Iraqi victims of the U.S. invasion encouraged Moroccans to sympathize with Iraqis and against Americans, especially as media coverage of the invasion by Arab news outlets depicted hostile attitudes toward Muslims and Islam among Americans. Satellite dishes, called

parabols in Morocco, are ubiquitous and inexpensive, and television viewership is high, with transnational Arabic-language news sources such as al Jazeera and al Arabiya watched widely.

Nonetheless, American cultural products, cultural forms, and formulas have been extremely popular in Morocco and would seem to have had a significant effect on Moroccan cultural production itself. Moroccan cinema, both popular and art cinema, has visibly adapted Hollywood formulas and “look.” Hip-hop has also become popular, and a generation of Moroccan rappers have used the form with a combination of highly local language and referents.

5 Moroccan discussions of sexuality and women’s rights have often taken up Western models for talking about identity, even while disputing the ways in which Americans understand Moroccan identity and sexuality. In the realm of consumer culture, the famous Moroccan souk (

suq) has been increasingly displaced by shopping malls and public spaces not only in the cosmopolitan capital cities of Casablanca and Rabat but even in the imperial cities of Fes, Marrakech, and Meknes. Higher education on the university level has been struggling with government-imposed reforms (themselves under pressure from International Monetary Fund directives), and American-style models for organizing curricula and degree programs have steadily been unseating long-held French models.

6What does the apparent contradiction between a Moroccan embrace of American educational and cultural forms and an increasing rejection of U.S. politics mean?

I argue that even though Moroccans identify many of these forms in circulation with the United States (even when the forms may not be explicitly American), they dissociate them from their putative culture of origin and do with them what they will. In other words, tempting as it might be to see films such as Mawchouma and Marock as taking up Western concepts of liberation and using them to open up Moroccan society to questions of “freedom” or equality, we should be aware that something else is going on.

In Morocco, as elsewhere in the Middle East and North Africa, outside cultural forms are taken up by local artists and authors, but they are recalibrated or reconfigured in ways that render them unfamiliar or incomprehensible to observers from the outside culture. This reconfiguration is not simply a question of a different language or local meaning that detaches the form in circulation from its own content. Rather, the Moroccan use of the Western form in circulation scrambles our sense of what those forms mean in their original context. It produces a version of what the late Miriam Hansen called a “global vernacular.”

7Moroccans so often make everything from Arabic language to popular culture their own with a creativity at once local and vivid. It is well known among Moroccans that their own work does not travel particularly well on its own. Moroccan Arabic is not understood by Arabs beyond the Maghreb and the North African diaspora. The phrase “ends of circulation” has a final and particular meaning in this country at the edge of the Arab world, the land of the farthest west.

The Moroccan case matters to this book for two reasons. First, with it we have yet another model for understanding and employing circulation to add to the repertoire of critical rubrics necessary for the new comparative literature and new approaches in sociocultural anthropology. And second, we understand some aspects of contemporary Morocco more fully if we recognize this era’s engagement with the outside form and distinguish it from the ways in which Moroccan cultural producers engaged French language and culture during the colonial and early postcolonial periods. Postcolonial criticism, strictly understood, is limited in helping us to understand the richness of these new situations. Moroccan filmmakers and writers since at least the 1980s have leveraged American works against French models because the American model is considered freer from the political oppressiveness of the former colonizer.

In my earlier work, I have asked whether circulation allows us to appreciate the strategies of contemporary North African cultural production with more nuance than does postcolonial theory, which seems generally to be better suited to the concerns of works from the 1950s through 1980s. For example, I followed

Casablanca the movie (Michael Curtiz, 1942) to Casablanca the city and found that Moroccan director Abdelkader Lagtaa disoriented the meanings of the Hollywood film for his own purposes while making the film

al-Hubb fi Dar al-Baida (Love in Casablanca) in 1991.

8 At that point, the Warner Bros. film

Casablanca, despite its stereotypes and Orientalism, might seem to a Moroccan director less noxious than French representations of Morocco because of the less fraught political relationship between the United States and Morocco in the early 1990s.

In the twenty-first century, however, as Moroccan attitudes toward the United States have become increasingly negative, the presence and popularity of American cultural forms do not necessarily implicate collaboration.

And so, rather than deconstruct the rich debate around Mawchouma in the winter of 2012–2013, I want to step back a few years to examine three turning points in the twenty-first-century Moroccan encounter with American forms and cultural products. Each of these turning points occasioned public discussion and significant debate and helps us to understand the most recent occasions for renewing that debate. And we must continually insist on attending not only to the meanings of these films, fictions, and other Moroccan cultural products but also to the social spaces in which they operate and make meaning. Doing so may mean thinking about Moroccan cinema in the spaces where it is viewed, from the illegally reproduced DVDs and VCDs to the mostly empty cinema houses where phone conversations compete with the soundtrack (as in my experience of watching ʿAla hafa in Rabat). And it means understanding that private encounters with novels by Abdellah Taïa or with films seen on laptops take place within a vibrant public debate that surrounds those private moments.

This chapter focuses on three episodes that advance this claim and that congregate around questions of gender and sexuality. First, I discuss the peculiar case of a Casablanca video pirate named Hamada and some of his work from 2003 to 2005. Then, I provide an extended discussion of Leila Marrakchi’s film

Marock and the debate around it. Finally, I discuss the work of openly gay Moroccan writer of fiction Abdellah Taïa. Any of these works and other newer works of Moroccan literature and cinema can be read and interpreted outside the framework I am proposing, but what I think makes them all especially worthy of attention is how they index—usually silently but in ways that resonate with local Moroccan audiences—foreign, recognizably American forms and formulas for representing identity yet do so in ways that detach them fully from their source.

“WA HAID AL MILOUDI”: SHREK IN CASABLANCA

The central idea for my work of the past decade came to me by accident—an overheard comment at a private social gathering in Rabat. It was March 2004, and I had just given a lecture at Mohammed V University drawn from the last chapter of my first book, which I was then in the process of completing. My host, Hasna Lebaddy, then the chair of the English Department at Mohammed V, held a small reception at her home after the lecture. Perhaps a dozen of her colleagues were there, and we sat around the perimeter of a room chatting over pastries and cakes. During a lull in my immediate conversation, I overheard a guest across the room ask her neighbor whether she had yet seen the newest “Miloudi.” The question received an especially positive response.

I interrupted to ask who Miloudi was. My colleague started to answer, but the other interrupted: “You won’t understand this.” I was, I admit, a little insulted, but I also took the remark as an intellectual challenge.

I pressed the question. I would simply have to experience Miloudi, she told me. My Moroccan colleague told me to go to the Rabat medina—that is, the walled portion of the old city, where much commerce is done—and walk down Mohammed V Avenue to the end, where the electronics suq was to be found. There, I would find several stalls where pirated DVDs, music CDs, and VCDs were sold. If I asked for “Miloudi” at any of them, the shopkeepers would know what I was talking about, and I would be able to purchase a creative work difficult to describe. It would probably just confuse me.

I succeeded in locating the disk without too much trouble. Video CDs were then a popular format in Morocco; with only 700-megabyte storage on a CD-ROM, however, the quality was notably poor, and the video jumpy and often pixelated. When I inserted the CD into my laptop, I encountered a curious work by a video pirate-artist who identified himself as “Hamada.” (His name, email address, and a cell phone number appear on a banner that runs across some of the video tracks.) Hamada and his collaborators had reproduced digital video clips from familiar American films using CGI and sitcoms and had dubbed them with Moroccan popular music and in some cases Moroccan dialogue. “Albums” of a dozen or so such tracks had been compiled, put on VCDs, duplicated, and sold for about $1 each (

figure 4.1).

In 2004, Hamada’s work was popular among young, urban Moroccans, selling thousands of copies and sometimes playing on screens in cafés. His most popular work, the one he came to be identified with, paired a clip from DreamWorks animated film

Shrek (Andrew Adamson and Vicky Jenson, 2001) with a

chaabi song that begins “Wa haid al Miloudi wa haid ah.” The video is of a dance number in

Shrek with the familiar character Donkey singing into a microphone while other characters dance (

figure 4.2). The music paired with this visual was a song by the Moroccan pop star Adil al Miloudi, here performing an exuberant piece in which he continually names himself and calls attention to his own drug and alcohol use. The song was already well known, but the juxtaposition of song and video, apparently perfectly synced but obviously not made for one another, endlessly entertained Moroccans in on the joke.

Although Hamada includes on his CD the banner with his name and cell phone number and makes the claim “All Rights Reserved,” the success of this particular piece was such that most of his future compilations were referred to as “Miloudi” (one that I bought on a subsequent trip back to Morocco later the same year demonstrates that they were released as a series). But others referred to them as “Cheb Hemar,” using the word cheb for rai or other pop stars in North Africa and the word for “donkey,” apparently referring to the donkey in Shrek featured in the dubbed video “Wa haid al Miloudi.”

Hamada’s creative work—or, more accurately, the Hamada phenomenon—deserves our attention here because of the original way this artist took up a foreign text—an American text at that, none other than

Shrek—and shaped it into a work of Moroccan art. Hamada was surely not the first to do this, and over the years that I have spoken about his works, I have been sent links or video clips of

Shrek paired with songs from multiple national contexts. (Despite my discussion of

Shrek in Iran in the previous chapter and a great deal of searching, I have never found an Iranian parallel.) Hamada’s version has always seemed the best to me, and it sparked an unusually popular phenomenon in Morocco. But Hamada’s originality is not, after all, my primary concern here.

FIGURE 4.1 Covers of Miloudi VCDs. (Photograph by Brian Edwards)

FIGURE 4.2 Hamada’s Shrek–Miloudi work.

Hamada’s “Wa haid al Miloudi” video is perhaps the paradigmatic example of circulation in the way I have been describing it throughout this book. Despite the building body of criticism of Moroccan literature, film, and visual culture, Hamada’s work has been neglected. To my mind, it is among the more innovative. It reflects in advance the ways in which film directors from Laïla Marrakchi and Faouzi Bensaidi to Nour-Eddine Lakhmari and Leïla Kilani would pick from American cultural forms and formulas as they created original Moroccan films. The starkness of what Hamada did makes it particularly compelling.

How should we make sense of his work? One option emerges from a short discussion of it in a prominent Moroccan culture magazine, the weekly

TelQuel, whose reporter tracked down Hamada in May 2004, at the height of his fame. Maria Daïf interviewed Hamada, then about twenty years old, and one of his collaborators (identified as “Majd”) in the coastal city of Kenitra. The interview is useful in particular because Hamada, understandably wary of the press, left little trace before he disappeared from view. In the brief

TelQuel interview, Hamada explained how the project had begun six years earlier, in 1998, when to amuse himself he dubbed a scene from Disney’s animated film

The Jungle Book (Wolfgang Reitherman, 1967) with

chaabi music. In that clip, included on the Miloudi VCDs, Mowgli and his animal friends from the jungle dance to a Moroccan popular beat. Hamada’s friends loved the work, and he put it on the Internet, which had been introduced in Morocco just a few years earlier, in 1995, and in limited fashion.

TelQuel does not go over the technological aspects of Hamada’s limited circulation except to say, “It was not until the VCD boom that ‘his clips’ could make the tour of the country.” Hamada explained: “I understood then that I didn’t have to put everything up on the web. Others downloaded the clips and sold them. I earned nothing.”

9Daïf herself focuses less on the ways the changing technology impacts Hamada’s work itself or its circulation within Morocco and more on extrapolating a traditional sense of the work’s meaning. Writing while Hamada’s works were still new and fresh, she concludes that they are best understood as the expression of youth who don’t see themselves reflected in Moroccan cinema and films: “What do young people do when they don’t recognize themselves in television dramas, Moroccan films, or Moroccan TV? They appropriate images from elsewhere and adapt them to their daily life and their language.”

10In some ways, this statement could describe the editorial mission of

TelQuel magazine in the first decade of the 2000s, whose motto was “Morocco as it is” and which was consistently courting trouble with the kingdom for pushing at the boundaries of what could be said and for defending cultural renegades. So it is little surprise to find this conclusion in the article on Hamada or indeed that the magazine thought to profile him. Here the understanding is that what Hamada is doing is finding a form to express Moroccan reality via the work of appropriation and adaptation. Fair enough, except that the concept of appropriation the article mobilizes runs against the journalist’s own sense of the work’s underlying realism.

Daïf writes: “You won’t hear [the dialogues and songs Hamada used] on Moroccan TV because they are too politically incorrect (they swear, speak of girls, hashish, money, and unemployment, the life of youth in the neighborhoods, to summarize). That’s why these dubbings are successful, in addition to the fact that the ‘décalage’ (Matrix speaking Marrakech dialect, for example) is hilarious.”

11 (This is my translation from the French. Daïf uses English to express the idea of political incorrectness; in the original she writes, “parce que trop politically not correct.”)

Without analyzing Daïf’s own reading of Hamada any further, we can note that she hits on a key aspect of Moroccan appreciation of his work: the humor or hilarity of what she calls the work’s “décalage.” What she means by the term décalage is the awkward or jarring juxtaposition of Moroccan dialect and Moroccan popular music with visuals from global media, in particular films with Hollywood high production values, which Hamada favored, such as Shrek, The Mask, any Disney film, and The Matrix. Of course, the high resolution and high production values of these film clips would be mostly lost in the transfer to VCD, where they would pixelate and jump. But they could still summon up a feeling of décalage, as Daïf put it.

Décalage is a notoriously difficult term to render into English with precision because it has multiple meanings. Brent Hayes Edwards has given us the most brilliant and extended discussion of its signification and the ways in which diasporic artists communicate via or across experiences of décalage. In his essay “The Uses of Diaspora,” Edwards writes:

[

Décalage] can be translated as “gap,” “discrepancy,” “time lag,” or “interval”; it is also the term that French speakers sometimes use to translate “jet lag.” In other words, a

décalage is either a difference or gap in time (advancing or delaying a schedule)

or in space (shifting or displacing an object)…. The verb

caler means “to prop up or wedge something” (as when one leg on a table is uneven). So

décalage in its etymological sense refers to the removal of such an added prop or wedge.

Décalage indicates the reestablishment of a prior unevenness or diversity; it alludes to the taking away of something that was added in the first place, something artificial, a stone or piece of wood that served to fill some gap or to rectify some imbalance. In other words,

décalage is the kernel of precisely that which cannot be transferred or exchanged, the received biases that refuse to pass over when one crosses the water. It is a changing core of difference; it is the work of “differences within unity,” an unidentifiable point that is incessantly touched and fingered and pressed.

12

When Edwards invokes the phrase “differences within unity,” he is referring to Ranajit Guha, who uses the term

décalage “to indicate a structural overlap or discrepancy, a period of ‘social transformation’ when one class, state bureaucracy, or social formation ‘challenges the authority of another that is older and moribund but still dominant.’”

13 Here, then, via Maria Daïf’s sense that what makes Hamada’s work intriguing and hilarious is that which she names

décalage, and through Edwards’s rich critical etymology of the term, we can open up the discussion of Hamada a bit further.

The so-called décalage—let us also call it the “disjuncture”—in Hamada’s tracks work against the realism that TelQuel otherwise attributed to it. In other words, if the magazine saw Hamada’s appropriation of Hollywood film clips as the result of his inability to find himself and his peers reflected in contemporary Moroccan cinema, there was also a greater and not so literal disjuncture. That which we could call the disjuncture, both temporal and geographic, between the soundtrack and the visual is the active space of possibility. It is that which is difficult to translate. But that space of disjuncture or experience of décalage is what makes Hamada crucial. Huge numbers of Moroccans got it. My colleagues at the party in Rabat were not confident that I ever could.

Playing with Brent Edwards’s use of Guha, we might be tempted to say that there was a structural discrepancy between what Hamada was doing in the Moroccan cybercafés in the Global South and what the high-paid CGI mavens in the DreamWorks studios were doing in the West when they created

Shrek, a sort of appropriation in a postcolonial sense. The risk that the West would recognize Hamada’s work as resistance (i.e., piracy) was always there, which is why Hamada had to stay incognito when the

TelQuel journalist tracked him down. But we should insist on not losing or forgetting the more exuberant aspects of the project—its hilarity. Many Moroccans expressed to me a sense of joy in the juxtapositions Hamada staged. When I pressed them further, they rarely stated that Hamada stole from the West and made an American product “Moroccan” but rather commented that the unexpected juxtaposition of the global and the local provoked an immediate and visceral reaction. That’s an important distinction.

We can go one step further by looking closely at Hamada’s most famous product itself—the Shrek piece reproduced on several of Hamada’s albums—for Adil al Miloudi’s lyrics are not without significance, of course, for the product as a whole. Hamada created the juxtaposition and did the digital work to bring Adil al Miloudi’s song together with the Shrek dance number.

The lyrics are straightforward but also elusive. It is a party song, where the singer is high on drugs.

Take a line and sniff it

And you will be so happy.

Look at Miloudi

He has taken drugs

And now is on the ninth cloud.

14

But then the singer appears to want not to be on drugs—to sober up:

I’m afraid lest I get drunk, lose my mind

And be bad to you.

So I’d rather drink milk.

The music is exuberant, pulsing, catchy. And then the lyrics repeat, with the first refrain in which the singer is on drugs returning after he has already renounced them. Perhaps most intriguing and difficult to translate is the opening line: “Wa haid al Miloudi wa haid ah,” which I discussed extensively with Sadik Rddad and Mostafa Ouajjani, Moroccan colleagues who helped me transliterate and then translate the elusive lyrics of the song. It is an invocation—a naming—of the singer himself but also a renouncing of his name. The term

haid means “to go away.” And because the dubbed track by Hamada is known as “Miloudi,” this evocation-rejection seems all the more interesting. Sadik Rddad says it means something and nothing at all.

Its hilarity, let’s say, is just this naming and then anonymity, the way Hamada brings forth Shrek and then brings forth Miloudi. It is a work that takes one of the most familiar icons of Hollywood film, Shrek, and makes it Moroccan but then plays off its foreignness at the same time. In this way, the work is illegible to an American audience. Its potent expression of décalage remains in the gap. Is it piracy? Is Hamada joking when he reserves his rights to this product? Does anyone in Hollywood care?

These questions were left unanswered, of course, while Hamada produced his massively popular VCDs. Moroccans were consuming his work, though Hamada himself was not profiting financially from his stunning success (his VCDs were easily pirated and resold by others). But just as Hamada was doing his original and unusual work, a young Moroccan filmmaker living in France, working in film more traditionally understood, was about to upset everything again.

MAROCK IN MOROCCO: ROCKING THE CASA

“The film of all the taboos,” it was called by its sympathizers. In the late spring of 2006, a controversial new film titled

Marock was all over the Moroccan papers and culture magazines. Made by a twenty-nine-year-old Moroccan woman named Laïla Marrakchi, who had left Casablanca for France a decade earlier, the film was released in Morocco on May 10, 2006, a year after it had premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and a month after its general release in France. These dynamics—a director with a Moroccan upbringing but a French address and a film about Morocco with French funding and a European provenance—would haunt the film. In Morocco, its arrival on local screens was heralded with the sort of media coverage of an American

succès de scandale, with the free publicity from excessive news coverage obviating the need for paid advertising. Indeed, multiple parallels could be made to Hollywood films, both within the film itself, its Hollywood look and American teen movie soundtrack, and in its wide distribution via both formal and informal circuits. Soon after its run at cinemas in Casablanca, Rabat, Fes, and Marrakech, contraband copies of the film were available for sale on the sidewalks of Moroccan cities, where it stood alongside pirated copies of Hollywood blockbusters such as

Syriana,

Jarhead,

Munich,

Ice Age 2, and

Cars, to name those with the broadest informal circulation in June–July 2006.

15 But if part of the surprise about

Marock’s reception in Morocco was just how Hollywood it all seemed, the controversies it provoked in Morocco revolved around the representations of Moroccan particularity within it.

Marock, Marrakchi’s first feature, builds on a theme she explored in her first film, a twelve-minute short called

L’Horizon perdu (Lost horizon, 2000), about a young man broken by life in the Tangier

medina who leaves Morocco for Spain in clandestine fashion. In the case of

Marock, however, the protagonist’s departure from the homeland is deferred for a full ninety minutes and comes at the conclusion of a coming-of-age tale. Though the protagonist in

Marock is no less broken by her milieu than the protagonist in the short, her elite socioeconomic status is never in jeopardy, and the emigration is legal and transparent (the last spoken word of the film is the passport control officer’s demand, “Passport,” which causes no anxiety). Nearly everything that precedes this final word justifies the departure, which comes both as a relief and as the tearful leave taking from adolescence and Morocco alike. The seventeen-year-old female protagonist’s departure from Morocco was not, however, what made

Marock controversial, even though the film associates Morocco itself with adolescence and departure from Morocco with the process of maturing. (To be sure, the film’s detractors repeated the fact that the director herself had emigrated from Morocco to France.)

16 Rather, the provocations were the director’s frank portrayal of premarital sexuality among elite Casablancans and her flaunting of religious and cultural conventions.

Three plot strands in particular stood out: the open refusal of the protagonist, Rita (Morjana Alaoui), to fast during the month of Ramadan, when the film is set; Rita’s mockery of her brother, Mao (Assad El Bouab), at prayer; and her open affair with a Jewish teenager, Youri (Matthieu Boujenah), an affair that is apparently consummated sexually. As the last plot element suggests, the frank treatment of teenage Moroccan sexuality and a disregard for the sanctities of religious tradition are in

Marock deeply intertwined. Across the board, the moment in the film that most disturbed commentators was an intimate scene between Youri and Rita, the two entangled in each other’s arms, kissing in an isolated seaside shed. Youri, following Rita’s eyes to the silver Star of David he wears around his neck, removes the chain and places it around the Muslim girl’s neck. “This way,” he says, “you won’t have to think about it.”

17 The film’s defenders, such as the liberal cultural magazines

TelQuel and

Le Journal Hebdomadaire, both of which featured it on their covers and dedicated long articles to it, found this scene the most difficult aspect to watch in its disregard for religious decorum.

18Its detractors used the moment as evidence that the film was part of a Zionist plot and were quick to discredit the director. Strong criticism was delivered to Marrakchi in person in Tangier, where the film was screened at the national film festival in December 2005, and online, where an active discussion about the film took place among the Moroccan diaspora in France on its French release in February 2006, taking Marrakchi to task for claiming to speak on behalf of the young generation of Moroccans.

19In the public debate that ensued upon the film’s general release in Morocco, Marock and Marrakchi herself quickly came to stand for multiple positions—freedom of speech, the young “rock” generation, intellectual and artistic honesty, and humanism, on the one hand, but disrespect for Moroccan tradition, diasporic elitism cut off from the homeland, neocolonialist pandering to Europe’s Islamophobic preoccupations, and savvy selfpublicity/provocation, on the other. These positions are not mutually exclusive, but the debate needs to be understood first.

The anxieties that

Marock provoked were intense across the cultural and political spectrum. Whatever the validity of the critiques of the film’s aesthetic quality

20 or whatever the anachronism of the film’s attempt to offer a national allegory of twenty-first-century Morocco via a tale of departure (which recalled mid-twentieth-century modes of the late-colonial and early-postcolonial period),

Marock struck a nerve. And if Marrakchi herself predicted that it would do so in a statement made in France before the film even got to Moroccan screens—a comment that in itself of course antagonized—her success in making this prediction is no less important to understand.

Marock makes vivid a variety of intertwined features of urban Morocco at a key turning point in the decade. It was one of the first feature films in Morocco to operate within diverse Moroccan media worlds, which I argue it both anticipated and helped to create. It was a film designed for the big screen in traditional cinema houses, of course, but it was more often viewed on pirated DVDs, shared via YouTube uploads, and discussed and debated online by a young public in Morocco and in the diaspora in France. This wide debate was an effect not only of its controversial and contemporary theme but of its addressing a public that has deep ties to Morocco as well as either transnational experience (the Moroccan diaspora in Europe) or transnational aspirations (urban Moroccan youth). If Laïla Marrakchi hit a nerve with her film, it was not simply because of the film’s explosive subject matter. Rather, she located and created a public whose nerve was ready to be struck. Marock was thus a harbinger of the new pressures on the Moroccan nation of the digital age.

Shana Cohen and Larabi Jaidi’s description of the Moroccan encounter with globalization, published in the same year as

Marock’s release, 2006, is useful in recalling the moment in which Marrakchi was intervening. In

Morocco: Globalization and Its Consequences, Cohen and Jaidi give an account of the interplay of economic and political pressures from outside and the protean forms that the Moroccan kingdom assumed in responding to the pulls and pressures of development.

21 They argue that Moroccan youth have retrenched into apathy and apoliticism, despite an environment that seems poised toward political inclusion. For Cohen and Jaidi, Moroccan youth can be seen in terms of what Susan Ossman has called the “lightness” of bodies in her own important study of the transnational circulation of forms of beauty between Casablanca, Paris, and Cairo, published at the beginning of the new millennium.

22 And though Cohen and Jaidi focus on economic and political processes, they suggest some of the forms of cultural production that may be implicated by attention to Morocco’s complex relationship to globalization when they pay brief attention to an anonymous Moroccan rapper in the diaspora who challenges from afar the cultural contradictions of Moroccan national culture. Marrakchi’s film depicts a segment of Moroccan youth who are apathetic and locates an outside form or look to tell their story. It was both aspects of

Marock that were provocative.

Marock was one of several Moroccan films that in the first half of the 2000s engaged the state of the Moroccan nation under a new set of arrangements that were no longer burdened by postcolonial anxieties.

23 Films as varied in their themes and artistic ambitions as

Baidaoua (Casablancans; Abdelkader Lagtaa, 1999)

, Ali Zaoua (Nabil Ayouch, 2000)

, Khahit errouh (Threads; Hakim Belabbes, 2003), and

Le Grand voyage (Ismael Ferroukhi, 2004), all of which commanded attention in different Moroccan and diaspora publics, were concerned with what place Morocco and Moroccan culture might have in a global setting in which ideas, products and commodities, lifestyles, and technologies had complicated what was once, perhaps, a more simple binary (France–Morocco). I say this without meaning to reduce colonial (and postcolonial) Morocco to a binary, either internally with respect to French division of Arab and Tamazight cultures, languages, and populations or globally with respect to the changing position of the United States toward Morocco (and that of Morocco toward the United States) in the late-colonial period and the first two decades of the postcolonial period. As I have argued elsewhere, from the arrival of American troops in Morocco in November 1942 and certainly after Franklin Roosevelt’s participation in the Casablanca Conference in January 1943, a vivid and visible triangulation of paradigms became available in Morocco, within which the American position might offer liberty from the French; the promise/threat of American commodities was the harbinger of this new paradigm.

24 To say so is not to confuse the American “alternative” as liberating, though that was the frame within which Roosevelt spoke to Mohammed V, but rather to identify it as an arrangement that would threaten to place Morocco in the time lag of American neoliberalism

avant la lettre. But even if we agree that the postcolonial period itself be reconsidered outside these binarisms, we must still note the shift by the end of the 1990s into a new set of concerns and ways of engaging with social collectivities in Morocco.

Marock was made in 2005 but set in 1997; it is thus sensitive to the moment before cell phones and the Internet pervaded daily life in Morocco but no less attentive to the new circulation of cultural objects in that setting, and Marrakchi and the film’s producers were acutely aware of the use of new technologies to market the film. In 1997, the opposition came to power in Morocco—the so-called government of alternance, a solution to the series of large and sometimes violent demonstrations against the legislative government in the 1980s and early 1990s. But after the death of King Hassan II in 1999, the stability of the monarchy was achieved in part by addressing the worst repression of the preceding years—through a truth-and-reconciliation process, the release of political prisoners, and the opening of press freedoms. These actions were not only necessary but also perhaps served to distract the Moroccan public from the opening to the world outside that new technologies of the digital age were forcing (from the fax machine and satellite television in the first half of the 1990s to the Internet and cell phones in the last years of the 1990s and in the early 2000s).

Films from the late 1990s through the mid-2000s leading up to Marock took up the theme of circulation in various ways and help us to see how a variety of interrelated aspects of movement and communication reflect on each other. Lagtaa’s film Baidaoua, for example, thematizes censorship and Morocco’s morality police (who represent the lack of free circulation). His protagonist’s desire to procure a restricted book anchors the film’s action. Lagtaa was less interested in the newer technologies (such as the fax machine) that were already putting pressure on state censorship in the early and middle 1990s and more in exploring questions of stasis and immobility as a challenge to contemporary Morocco. The book Salwa wants is available in France, and to procure it may require her to leave the country, but in another scene an Islamist teacher instructs his pupils that the Qurʾan is good for all times and places. Lagtaa suggests that circulation—the circulation or censorship of a book—returns Morocco to contemporary temporality, whereas a more fundamentalist strand of Islam in Morocco conjoins stasis and being out of time.

Other films seized on the intervention of technologies in altering the nation’s spatial and temporal bases, which would soon be apparent when cell phones became massively available in Morocco. Ismael Ferroukhi’s film

Le Grand voyage, a road movie from Paris to Mecca, portrays the cell phone as a technology that challenges the authority of face-to-face contact and symbolizes the generational gap. Hakim Belabbes’s film

Khahit errouh (Threads), an experimental, avant-garde film, associates the ruptures of generational and diasporic change, of its shift in setting from Chicago to Boujjad, and perhaps of its own avant-garde fragmented technique with the interruption of the telephone, a technology that both connects and ruptures. And

Ali Zaoua, a greatly successful film both locally in Morocco and internationally, demonstrates in two ways a sense that the world of young street children may be seen in relationship to the technologies and economic forces of globalization. Nabil Ayouch’s framing device for his tale of Casablanca street children is to show Moroccan media depicting these marginalized youth to the larger nation, suggesting both the social stratification to be found in Casablanca and the media worlds located there. But

Ali Zaoua is notable among Moroccan films of the decade in its use of digitally generated animation to depict what these children imagine. The street children of

Ali Zaoua are caught in social and economic stasis, but their imaginations allow them to circulate outside their immediate circumstances. Ayouch thus seizes on a metaphor that Moroccan sociologist Said Graiouid would pick up on in his own research on social exile and virtual escape in Morocco. Graiouid’s ethnographic research in Moroccan cybercafés found that otherwise hopeless youth were chatting with Moroccans living in diaspora and engaging in “virtual h’rig” (referring to the illegal form of emigrating—literally, “burning”).

25With these descriptions, I do not mean to imply that the question of the nation is not central to many of these films. Yet even narratives that are centered around the nation or a critique of the nation must be considered in the changed framework within which the nation operates, globalization.

26 For

Marock, sensitive to the global movement of ideas, images, bodies, and commodities (to say nothing of politics and technologies), awareness of this framework is crucial to judging the film and whether Marrakchi’s national critique is anachronistic or daring or both. In

Baidaoua, awareness of this context allows us to see how the film is concerned primarily with circulation, whether one can move socially, across borders, within a city or not. In

Ali Zaoua, taking this in another direction, social immobility is contrasted with the mobilities represented by media and digital animation. To shift the conversation to “circulation” is in part to register frustration with a logic that insists that all Moroccan cultural production forever after 1956 is in reference to France and to insist that other concerns and other networks have in fact taken center stage in recent years.

27 Marock’s intertwined set of concerns include questions of circulation, diaspora, cultural clash, friction with (or rupture from) Moroccan traditions, which together suggest that the analytics of postcolonialism do not apply here

even though postcolonialism may be the register within which Marrakchi imagines the narrative resolution of her film via Rita’s departure from Morocco to France.

But

Marock is notable, too, for the way in which American objects, songs, and a “Hollywood look” run through it when the film otherwise is not geographically or politically concerned with the United States. Here we have a vivid example of how Moroccan cultural production in what I call the “digital age” or, alternatively, the “age of circulation” is animated by a different set of concerns than the concerns that were dominant during the postcolonial period. Maghribi cultural production during the first three decades of the postcolonial period, which commenced in Morocco with independence from the French protectorate in 1956, frequently exhibited an anxious relationship to French history, culture, and language—major examples include Abdelkebir Khatibi’s novels

La Mémoire tatouée (Tattooed memory, 1971) and

Amour bilingue (1983;

Love in Two Languages [1990]) as well as Abdellah Laroui’s work of revisionist history

L’ histoire du Maghreb (The history of Morocco, 1970). By the 1990s, however, the concerns of younger Moroccan writers and filmmakers seem to have moved beyond the classic postcolonial concerns and taken up a new set of themes I associate with circulation, both literal (migration, travel, expatriation, etc.) and formal. We see an engagement with circulation earlier in cinema (for example, in Abdelkader Lagtaa’s film

al-Hubb fi Dar al-Baida) than in Moroccan literature, perhaps because influential American cinematic representations of Morocco (such as

Casablanca) were an early harbinger of the later geopolitical order that would follow the colonial era. The interest in circulation as a theme can be traced through Moroccan literature beginning in the second half of the 1990s (e.g., Aicha Ech-Chana’s socially committed documentary text

Miseria [1996] and Soumya Zahy’s novel

On ne rentrera peut-être plus jamais chez nous [We will perhaps never return to our homes, 2001]). Writers of the various Moroccan diasporas—such as Abdelkader Benali, writing in Dutch in Holland; Laila Lalami, writing in English in the United States; and Tahar Ben Jelloun, writing in French in France—were sensitive to the theme of migration and return, as might be expected. Benali’s novel

Bruiloft aan zee (1996;

Wedding by the Sea [2000]), Lalami’s first book of fiction

Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits (2005), and Ben Jelloun’s book

Partir (2006;

Leaving Tangier [2009]) all narrate tales of Moroccans in motion to and from Europe.

Marock is less aesthetically or narratively original than these works. Lagtaa’s Baidaoua, which summons an innovative visual technique in the service of a complex narrative exploration of circulation, is significantly more original from an aesthetic point of view, and Benali’s Wedding by the Sea is formally exuberant and linguistically inventive. But Marock is nonetheless successful in making clear the forms of social organization produced by and within the age of circulation.

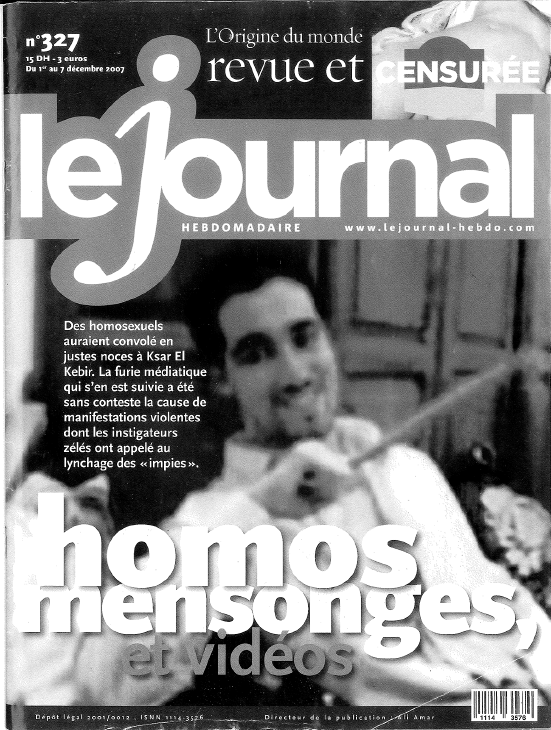

In its coverage of the debate over

Marock, the maverick weekly

Le Journal Hebdomadaire staged a debate between Bilal Talidi, a representative of the Islamist Parti de la justice et du développement (PJD), which had called for banning the film, and Abdellah Zaazaa, the leader of a network of Casablanca neighborhood associations, Réseau des Associations de Quartier du Grand Casablanca, and representative of a liberal, secular position. In the debate, printed in the pages of

Le Journal, the question of aesthetics became a screen against which to argue larger questions about Moroccan society. Talidi, who had published an editorial against

Marock in the paper

Attajdid, claimed in the pages of

Le Journal that “one should not judge a film without watching it.” His indictment of the film was, in this venue, pitched in terms of aesthetics: a “maladroit” use of French and Arabic, an “extreme lightness of plot,” and a lack of “dynamism, drama or life”; for him,

Marock was closer to a documentary than to a “true film.” Zaazaa, in contrast, resisted the analysis of the film’s language or aesthetic quality and launched his own defense of it on political grounds. The film’s ability to “trace Moroccan realities,” in particular, justified its screening in Morocco, and he called attention to the ways in which its opposition was manipulating the film for its ulterior motives of creating a “state of law” (

état de droit). But he, too, made recourse to aesthetic judgment. He noted: “I saw the film in the company of my wife. We left struck [

boulversés] by how well it had traced Moroccan social realities. The story pleased me in every way.”

28The point that Zaazaa had seen the film in the company of his wife was clearly part of his implied defense. If

Marock posed a challenge to “traditions of the country,” “religious values,” and the “fundamentals of Islam” (as religious politicians had suggested, including those who did not call for its censorship, but rather for a national boycott of it),

29 Zaazaa claimed that the film could educate the Moroccan conjugal couple on the new realities of Moroccan society. But Talidi called Zaazaa on the latter’s expression of “pleasure” on seeing the film, which Talidi said was not an “objective response” and therefore to be discarded. He claimed such objectivity for his own analysis of the film; Zaazaa’s pleasure was subjective.

Marock, the viewing of Marock, the response one had to the viewing of Marock, and what the nation’s appropriate response to Marock should be in 2006 became fraught places to debate the status of national culture itself. Talidi’s comment about Zaazaa’s pleasure begs the question of an “objective” reading. How do we read this film? Can an “objective” reading of the film by a representative of a political party stand in for that of a citizenry?

Talidi and Zaazaa notably agreed that

Marock offered a representation of Moroccan reality, though they did not call attention to their agreement on this question. For Talidi,

Marock was more documentary than film; for Zaazaa, it was a shocking representation of a reality he recognized but about which he knew nothing. Their implied disagreement was over what role the elite and westward-looking Moroccan youth of

Marock might have in the society at large. It is the teen look of the picture, inscribed within a style deeply redolent of American cinema, that was perhaps the most upsetting, though these terms were not used in the debate. PJD’s call for the film to be banned drew on the law’s defense of “sacred values and good morals.” Therefore, the question of whether the film was Moroccan or not could be linked to whether it should be banned under Moroccan law. Marrakchi’s Moroccanness or her Frenchness was itself a cipher for a question of

style and what I call the film’s “look.”

On the level of style,

Marock itself exhibits the circulation of an American look, which is doubled by the film’s interest (both visually and in the narrative) in American commodities. This interest is the threat that is harder to speak of, but the one that made the PJD position ultimately anachronistic, as other commentators realized. Mohamed Ameskane, representative of the Union pour un mouvement populaire (known best by its abbreviation, UMP), stated in the same pages that the film could be boycotted “if it were judged contrary to our principles. [But] one must sign up for this new world, the world of the Internet and of globalization.”

30 Seen in this light, many Moroccan commentators’ resistance to

Marock should be regarded as aligned with an anxiety about globalization, and the championing of it on grounds of free speech can be viewed as a celebration of the open borders (of both information and trade in commodities) associated with globalization. My point is not to take a side but to show that

Marock heralds but does not initiate a new stage in Moroccan cinema. From

Marock, we can look backward to see this interest in circulation in a number of places and forward to the works that would come, such as those with which I began this chapter. But first we must describe how a “look” circulates.

The story

Marock tells is familiar enough to those who have watched Hollywood teen romances, and on the level of plot it borrows from a number of Hollywood films and TV serials. To say so is not to denigrate it per se—nor is it a compliment on artistic grounds—but rather to note why the familiarity of the formula might itself be so bothersome to some Moroccan critics such as Talidi and also why for others it immediately raised the question of protection on the grounds of free speech. The circulation of this look operates on both the level of plot/scenario (which allowed politicians to target the film) and the level of the film’s visual and aural registers (which politicians did not invoke).

Marock borrows what we can call, following Miriam Hansen again, a vernacular familiar from Hollywood cinema, in this case the teen romance, and brings it into Moroccan circulation. That combination of a familiar look and the familiarity of a Hollywood formula, the problem-picture-cum-teen-romance, emerges as the most interesting form of global culture in circulation in this film. But we can also note the many explicit indications of global circulation in the film: the music, apparel, food, products, and commodities that animate the world of these Casablancan youth. If these youth look to Europe for their futures after the baccalaureate (“bac”) exam, the commodities, products, and culture that they consume are for the most part American. More accurately, these objects of consumption are global and are generally rendered in global English, both of which are associated with the United States irrespective of the national origin of the cultural product or artist.

Marock is a teen pic, which seems at once a comfortable and uncomfortable way to describe it, given that the phrase implies an American relationship to the family and society that was and is not the norm in Morocco. In other words, without the particular identity of “teens” that we know in the United States, which is not universal, you can’t have a “teen pic.” However, as

Marock itself demonstrates, not only does “teen pic” sound appropriate as a way to describe the film, but the film so successfully mobilizes this style to describe a social milieu that it effaces for its non-Moroccan audiences much of the particularity of Moroccan adolescence. Such particularity is swept away by

Marock’s depiction of a world of discos, parties, romance, and preparation for a life after high school that will be spent in France. Whatever the accuracy of this representation of the young elite of Casablanca, it is clearly not the life enjoyed by most Moroccans. (Juxtaposing

Ali Zaoua, with its representation of the poor homeless children of Casablanca, and

Marock, the two Moroccan films of the first decade of the twenty-first century with the largest international success, would be provocative.) With poverty and social class for the most part dispensed with by

Marock’s fascination with the elite, the problems that remain in the social problem aspects of the film are those presented by Moroccan society itself. Perhaps, then, it is not surprising that the solutions to those problems are also brought in from abroad (American music, for example, and the characters’ choice to depart from Morocco). The way the Hollywood “look” functions, therefore, is to naturalize the import of foreign solutions to domestic problems and to make domestic recalcitrance to them seem itself foreign or anachronistic. That is, the film’s adoption of an American vernacular, within which the social problem of a romance between a Jewish young man and a Muslim young woman may be overcome naturally by the power of love (and romantic comedy as a genre), was a solution that made most Moroccans’ difficulty in imagining it seem irrelevant or retrograde. Indeed, the film ends in tragedy with respect to the love story, not the comedy it has suggested, which we may see as the translation of the vernacular to local realities. This relationship to the Hollywood vernacular is the deep level on which Marrakchi’s outsider perspective functions, and, though unnamed by its opponents, it produced the relationship to Morocco that many found bothersome about the film—and that titillated others. Without the language to discuss this vernacular as that which was foreign to the Moroccan film, however, the debate revolved instead around the question of Marrakchi’s roots as a Moroccan and the route she took to France as ways to prove that she and therefore her film were not after all “Moroccan.” This approach, it should be clear, was a dead end.

The story is a simple problem tale set during the month of Ramadan. Rita is a high school senior; it is the year of the baccalaureate exam, a year that in her circles is spent studying, partying, listening to music, and thinking about the next stage of life. For Rita and most of her friends at the privileged Lycée Lyautey, the next stage of life often means leaving Morocco for Europe (though not in all cases); the present is generally met with abandon. Drinking alcohol, smoking hashish, flirting, and being sexually active are the norm for weekend nights, which are spent racing around in sports cars between nightclubs and homes without parents, where prostitutes may be called in for quick fixes for the boys. Rita’s brother, Mao, has returned home from London for Ramadan, and from the start we can see that he does not approve of Rita’s milieu. We see Mao praying, to his sister’s surprise, and wearing a close-cropped beard; he is clearly disturbed by the frivolities of his old circle of friends. He rarely comments directly, except to Rita, who he says looks like a “whore” because of the makeup she wears. At a party, Rita falls for a young man she has observed at a nightclub. She learns his name (Youri) through a mutual friend and bets her friends that she’ll have him by the end of Ramadan. The problem, though, is not whether she can or will have him—there are meaningful glances between them from the start that make this clear—but what it will mean if she does.

Youri is, after all, a Moroccan Jew, and although this detail seems to bother no one too much in the present (except Mao, who is teased by friends and reports it to his parents), the fact that these young people’s future is always on their minds poses the question that Rita rarely asks herself: Can this relationship have a future? Learning about Rita’s social life from Mao, Rita’s parents ground her until the bac is over and done with. But she escapes, consummates her affair with Youri, passes her bac, and worries about what to do with her romance if it cannot be shared openly. She suggests to Youri that he could convert to Islam; he suggests the same to her about Judaism. No sooner have they discussed these options than Youri is killed in a car crash. Rita, distraught, retreats into herself. Her brother apologizes for his part in her unhappiness. They reconcile. Two months pass. Rita leaves for Europe.

The plot is fast and efficient. The film is visually sensuous; its world is socially vapid. Rita, played by a newcomer to the cinema whom Marrakchi plucked from Paris and who admitted in interviews to being from the same elevated Casablanca class that is depicted in the film, is attractive and starry-eyed. (Morjana Alaoui was in fact a student at the American University in Paris when Marrakchi cast her in her first film role; after passing her bac in Morocco, she had lived in Florida. Her own pathways neatly demonstrate the triangulation of the colonial, postcolonial, and global that I have discussed.) She is also barely clad much of the time, in-close fitting tank tops and boxer shorts, in a string bikini another time, or faded Levis, costuming choices that are both part of the film’s verisimilitude in representing the young Casa elite—from press photos and in film festival appearances, it was striking how much Marrakchi herself looked and dressed like her own characters

31—and part of Marrakchi’s juxtaposition of the visual appearances of the libertine Casablancan youth and the more traditional members of the community.

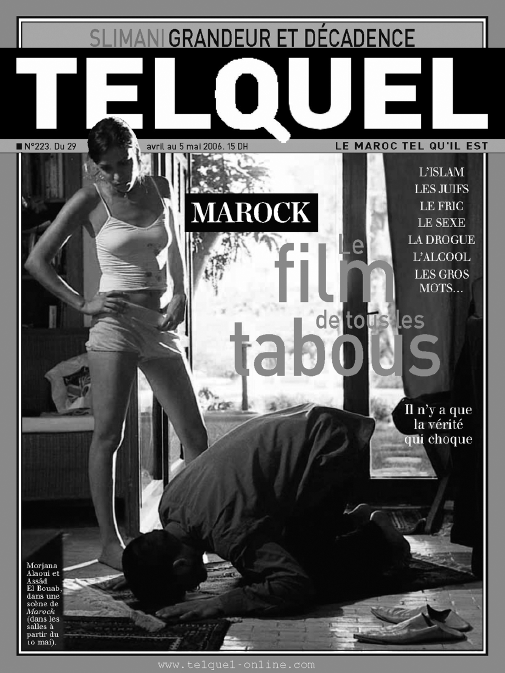

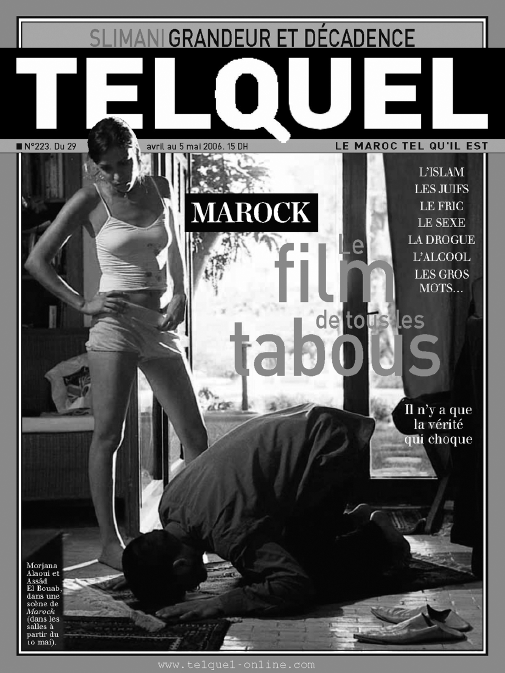

The most famous example of this juxtaposition appears in the film still that was circulated as part of the film’s publicity and featured on the cover of

TelQuel. In the still, Rita wears skin-tight shorts and a cotton camisole, hand on hip, navel exposed, and stands over her brother bowing in prayer. In the film’s scene, she provokes him: “Are you sick or what? What are you doing? Did you fall on your head?” Then, more aggressively: “Do you think you’re in Algeria? Are you going to become a fundamentalist [

barbu]?’” The pose, reproduced on the cover of

TelQuel next to the words “the film of all the taboos,” presents a vivid example of the changing look of young women in Casablanca not only in terms of clothing and brands but in terms of body size and type itself (

figure 4.3).

During the period in which

Marock is set, the late 1990s, sociologist Fatima Mernissi was writing columns in the Casablanca-based women’s magazine

Femmes du Maroc that remarked on the generational shift of young Moroccan women increasingly toward Western body types as models of beauty; Mernissi lamented this shift as she called for Moroccan women to resist the emaciated “waif” look of then prominent models such as Kate Moss.

32Mernissi’s comments on the ways in which Moroccan women’s body types could represent a form of cultural circulation and Susan Ossman’s subsequent ethnographic work that charted the transnational circulation of Western models of beauty and body type open up the ways in which we can discuss the Western look of Marock, both in terms of the individual actors, their bodies, and their clothing and in terms of the cinematic vernacular that Marrakchi mobilizes. It is, after all, the look thus conceived that is the most immediate presence of America in a film that only once invokes the United States as a geopolitical entity (and then quickly dispenses with it as a place where the characters know “no one”). Nevertheless, America plays a major, if imagined and silent, presence in the film. Marock thus presents itself to us not as a film that is postcolonial but rather as one that inhabits the era of circulation in an interrelated series of ways. Before we come back to the literal markers of this presence of global culture, we need to return to the more slippery question of what I have referred to as the film’s Hollywood “teen pic” vernacular.

In several essays, the late Miriam Hansen presented a powerful argument that broadens our understanding of what she calls the “vexed issue of Americanism” for transnational cinema studies—namely, the ways in which “an aesthetic idiom developed in one country could achieve transnational and global currency.”

33 Her focus was on the circulation of the classical style of Hollywood cinema produced during the dominance of the studio system, roughly from 1917 to 1960), and on the ways in which that style has been translated and differently understood in a variety of other national cinemas—most notably Shanghai cinema. There are at least two lessons from Hansen’s rich work that I want to apply here. First is her analysis of the way in which classical narrative Hollywood cinema masks the “anachronistic tension” of its “combination of neoclassicist style and Fordist mass culture” (66). The anachronism of classical cinema is that it took on neoclassicist aesthetics (it is readerly and transparent and has linear narratives, coherent subjects, and so on) even while it was an art associated with the new and the modern, both as a new technology and with respect to the Fordist mass (cultural) production perfected by the studio system. By naturalizing its own form of narrative, Hansen argues, classical Hollywood cinema developed a rhetoric that could in fact articulate “something radically new and different under the guise of a continuity with tradition” (67). Part of what is articulated is the very messiness of Fordism and modernity itself, with its various forms of structural and literal violence and how (certain) individuals could find a place in that system. Hansen’s second lesson, then, follows from the first and is related to my discussion of circulation: that Hollywood cinema traveled so well and so much better than other national cinemas because of the way it “forg[ed] a mass market out of an ethnically and culturally heterogeneous society, if often at the expense of racial others” (68). This “first global vernacular” worked because classical Hollywood cinema mobilized “biologically hardwired structures and universal narrative templates”; mediated competing discourses on modernity and modernization; and “articulated, multiplied, and globalized a particular historical experience” (68). Hollywood cinema found its way influentially into other national cinemas not because classical cinema universalized the American experience but rather because it was translatable. “It meant different things to different publics, both at home and abroad,” Hansen writes (68). On the level of reception, the Hollywood films and that which might be taken from them (their rhetoric) could be changed, localized, and adapted.

FIGURE 4.3 The provocative cover of TelQuel, April 29–May 5, 2006.(Reproduced with permission of TelQuel Media)

What I want borrow from Hansen’s work is her discussion of the contradictions that the classical style masks and allows as well as her sense of how that particular conjunction itself is particularly well suited for global circulation. With these notions, we can revisit the discussion of “cultures of circulation” that Benjamin Lee and Edward LiPuma advance and balance the temptation to read for meaning with attention to what Dilip Parameshwar Gaonkar and Elizabeth Povinelli call the “circulatory matrix.”

34 Marock’s engagement with a Hollywood vernacular—no longer the classical vernacular, pure and simple, though at most times borrowing from it—allows it to smooth over some of the more troubling aspects of economic globalization that affect the world behind that which is represented in the film. The film does repeatedly attend to class and economic differences, even while too comfortably keeping them at the margins. But this smoothing over of the crises of economic globalization happens naturally, as it were, in the fluid way in which

Marock adopts the cultural style or look of the Hollywood teen pic. In other words, the ways in which the film may be seen in terms of “globalization” are multiple and reinforce one another: the circulation of the Hollywood vernacular and the fascination with American cultural products and commodities serve both to double the elite characters’ ability to circulate across national borders and to efface the ways in which the Moroccan underclass may not. When Rita’s friend Asmaa (Razika Simozrag) tells Mao that she will not be relocating to Europe after the bac because her parents don’t have the means, he does not know what to say. Mao’s surprise—“je [ne] savais pas,” he mutters and looks down—is echoed, as it were, by the film’s inability to dwell on those who do not circulate. Though the film notes these individuals who represent dead ends, it cannot itself resist always remaining in motion.

Marock, to be clear, is most fascinated by upper-middle-class teenagers in Casablanca, a group whose own ability to circulate is strikingly more capacious than that of other Moroccans. This is a point the film does suggest, most vividly in a climactic scene when Rita denounces her parents for paying off the family of a young poor child whom Mao apparently struck with his car and killed at some time in the past. Although the film does offer sympathetic portraits of working-class Moroccans as minor figures (most often as servants, by which it offers an additional critique of upper-middleclass Moroccan family values), its portrait of Morocco is clearly delimited to a small portion of the population. That it did apparently speak to a much larger public than it represents, though, should not be doubted, in part perhaps because of its own subtle critique of class dynamics, but otherwise because of the apparent translatability of some of its characters’ aspirations to other social classes among Moroccan youth. Nevertheless, the visual pleasure the film takes in depicting the sumptuous residences, cars, parties, and bodies of Casablanca’s elite allies it with the Hollywood teen pic and not with class critique. To be sure,

Marock is not a critique of globalization, either economic or cultural.

The immediacy and power of the Moroccan debate around

Marock with which I began this discussion, then, can be seen as the resistance from Moroccans left behind by those very processes of globalization, both cultural and economic, that Marrakchi’s film represents and enacts. Hansen’s crucial point that the classical style was anachronistic because it was neoclassical and modern—which I would recast as “preposterous,” meaning simultaneously “before” and “after”

35—may be applied to Marrakchi’s translation of the Hollywood teen pic. In this sense,

Marock is a film that struck many Moroccan viewers as new (Zaazaa’s comments given earlier), and yet it is a film that is clearly nostalgic for a different form of looking at and being in the world, a world before the advent of digital technologies.

Marock offers the newness of a modern Morocco, engaging the putatively taboo topics of teen sexuality and interreligious relationships while playing a reassuringly retro soundtrack—some of the songs featured most prominently are “The Power” by Snap! (1990); “Rock’n’ Roll Suicide” by David Bowie (1972); “Shake Your Groove Thing” by Peaches and Herb (1978); “Sad Soul” by Ronnie Bird (1969); and “Junk Shop Clothes” by the Auteurs (1993). This retro soundtrack hints at the retrograde anachronism of Marrakchi’s resolution of her tale. The nostalgia for a world before digital technologies overwhelmed daily practice substitutes for or overlays smoothly, as I have suggested, an allegory of the Moroccan nation for the more complex situation of contemporary Morocco in the age of circulation. That is, the way in which

Marock proposes itself as something radically new on the Moroccan cultural scene and then delivers in multiple ways something more comfortably nostalgic is the way in which its look and soundtrack betray the trap that the film slips into: the idea that national allegory provides an adequate mode within which to comprehend twenty-first-century Moroccan reality.

In

Marock, the interplay of the new and the nostalgic is associated throughout with the Hollywood look. The camera savors the streets, the exteriors and interiors of the wealthy Anfa neighborhood of Casablanca, to a slow sensual rock-and-roll soundtrack. Even to those who have been to privileged neighborhoods of Casablanca and Rabat, the scenes depict an almost impossibly wealthy milieu.

Marock includes several scenes that do nothing to advance the plot but that are nonetheless crucial to comprehending its meaning: a car chase through the streets of Anfa; young people sitting around swimming pools, nightclubs, and outdoor cafés. They curse, they drink alcohol, the young men harass the female maids. The film’s global audience and its Moroccan audience alike are in a familiar world, but one not familiar from film images of Morocco in general or of Casablanca in particular. It is instead a world familiar from TV and Hollywood images of Beverly Hills. The language of the film is for the most part French (only the servants speak in Moroccan Arabic), a choice that Marrakchi defended on the grounds of realism.