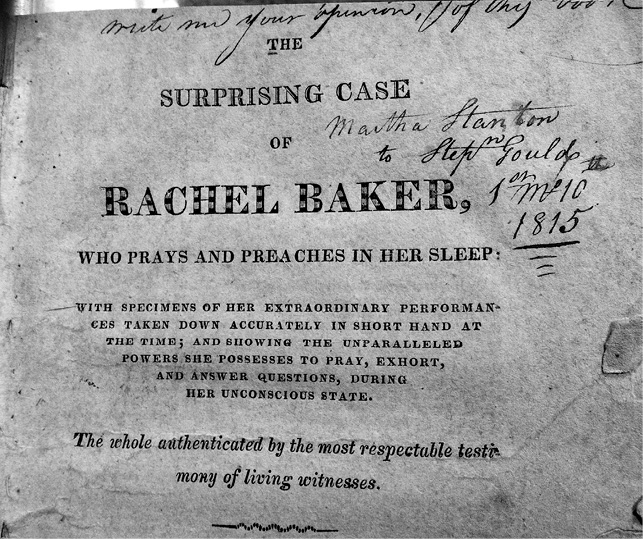

One of the pamphlets of 1814 featuring Rachel Baker, “who prays and preaches in her sleep.”

Eliza Champlain Sees Angels Over Connecticut

A sympathy seemed to arise between the waking and the dreaming states of the brain at one point—that whatsoever I happened to call up and to trace by a voluntary act upon the darkness was very apt to transfer itself to my dreams.

—Thomas De Quincey, Confessions of an English Opium-Eater

After leaving the presidency in 1809, Thomas Jefferson retired to Monticello, his mountaintop estate in central Virginia. He stayed as far as he possibly could from the corridors of government. But he still received inquisitive letters from people he knew and just as many from citizens he had never met before. One in particular—among the longest ever addressed to him—came from the hand of one Miles King, who lived on the Chesapeake Bay.

“Dear Sir,” it began. “It is not without a considerable struggle in my mind arising from the conflict between a conceived duty, and many weighty and powerful objections, that I have ventured at some length to address you on the all-important subject of vital religion.” They had been introduced once, in 1806. The writer, an obscure former navy lieutenant and ship owner, had been won over, he said, by the president’s “politeness” and “urbanity.” This seemed to qualify him to take extra-special care of his fellow Virginian’s soul.

When he finally got around to explaining the impetus for his long letter, King stated that he had awakened at midnight after a dream—“something about you” was all he said about it—and it prompted him to concentrate his thoughts on the great man’s “spiritual estate.” A good many pages later, as he attempted to wind down his letter, he assured Jefferson that there was “no neuter ground” in religion and urged him to “give Christianity your firm support.” In praying for Thomas Jefferson’s soul, Miles King took solace in something he had supposedly heard spoken in the light of day, to the effect that Jefferson was immersed in studying the Book of Isaiah, with its multiple dramatic prophecies.1

Embracing freedom of conscience, his only certain gospel, Jefferson strenuously sought to keep his ideas about truth and religion to himself. He tended to his farms and to his family, and for a dozen years after King’s sprawling letter, he read voraciously. As a young man, he had jotted down bold words of Cicero: “The man who is afraid of the inevitable cannot live with a soul at peace”; as an old man, he wrote conventionally to his peers in the expectation of an end to life that led to an “ecstatic meeting with the friends we have loved and lost.” Then, in the first days of summer, 1826, worn down by debts and intestinal troubles, the eighty-three-year-old former president lay on his deathbed. Something was about to happen that the late Dr. Rush had eerily foreseen and that his fellow Americans, always eager for sensational news items, were to find irresistible.2

Whenever early newspapers announced the deaths of famous citizens, they enclosed their columns within black borders. But this singular (or dual) event went beyond what Americans had ever encountered in their first half century as an independent republic. The perfectly timed departures of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson on July 4, the day they helped make famous, left the nation dumbstruck. It prompted eulogists far and wide to wonder—quoting one representative newspaper—at “a coincidence marvelous and enviable. . . . It cannot be all chance.”

Skilled orators knew how to exploit the founders’ deaths. In Fayetteville, North Carolina, Henry Potter, whom Jefferson, as president, had appointed to the federal bench, spoke to a crowd in words that remind us of Dr. Rush’s dream of the Last Judgment: “And on the memorable 4th of July, the Jubilee of American Freedom, while the cannon’s peal was roaring, the trump of jubilee sounding, the acclamations of joy floating in the heavens. . . .” It was repeated by a eulogist in Newark, New Jersey: “The sound of the Trumpet of Jubilee is reverberated in strange and mysterious echoes.” Invariably insisting, in prefatory remarks, that they were immune to all superstition, editorialists in various cities and towns nonetheless evoked the collective belief, generated by a seemingly impossible conjunction, that “the Ruler of Events has chosen to manifest by a signal act of his Providence” the principles laid down by America’s founders.3

Though Jefferson wrote nothing about the substance of his dreams, he did dwell on the nature of memory and the mind. He was often captive to those “fugitive” moments when sentimental “reveries” took over. Away from his daughter, he wrote her that nothing was so “soothing to my mind” as these indulgences, which involved their past travels together and served to “alleviate the toils and inquietudes” of political life. In 1819, long past active politicking, he wrote of the confidence that he lodged in his two immediate successors as president, James Madison and James Monroe: “I willingly put both soul & body into their pockets. . . . I slumber without fear, and review in my dreams the visions of antiquity.” He was being literal, though perhaps less in the content of his dreams than in his reference to the reading matter that he most favored in retirement: ancient Greek and Roman thinkers. Their “visions,” as classicists who have studied Jefferson show, put him in loving touch with lyric poets and keen philosophers. His imagination flew to “the heroes of Troy” and to Epicurus, wherein he found, in the words of Karl Lehmann, “that there was no dualistic contrast between ideas and reality, spirit and flesh.” This also meant that, despite the “ecstatic meeting” with friends of whom he sometimes fantasized, he had serious doubts about the likelihood of a soul existing separate from the body after death.4

His own political history was never far from Jefferson’s thoughts, and on the day before his death, given the opiate laudanum to ease bodily pain, he dreamt of the Revolution. It was war again in his still fertile mind. As his grandson looked on, Jefferson went through the motions of writing out urgent letters. He spoke deliriously about the Committee of Safety, which in 1775–1776 had stood guard against the British invaders. “Warn the Committee to be on the alert!” the dying man called to the people his imagination were producing at that moment.5

One year before, Jefferson’s favorite granddaughter, Ellen, had married Joseph Coolidge, an international trader from New England. Consequently, she did not arrive back in Virginia in time for a last audience with the dying patriarch. Two years later, however, she wrote from Boston to one of her sisters that her memories of life at Monticello kept returning to her when she went to sleep. Though the walls of the historic home were now bare, and the family obliged to sell everything to pay off Jefferson’s debts, Ellen was comforted in her dreams, where the best in nature crept into her mind. Of the senses activated, it was hearing that most affected her:

In my dreams I sometime revisit my home, but it is strange that I never find myself within the house. I am always wandering through the grounds or walking on the terrace, & the weather is always delightful. I hear the gentle breathing of the wind through the long branches of the willows, & see them wave slowly, whilst on the other side the aspen leaves quiver & tremble with a justling as distinct as ever delighted my waking ear.

Quivering, trembling, breathing—she heard as much as she saw in her dream.

Ellen Coolidge was thirty-one, a mother; but in her dreams of Monticello, she told her sister, she felt sixteen again. Her young children were absent from her thoughts, as she regressed and regained a life she once knew. It was invariably the same paradisal vista, and it existed under a sunny sky. And so she concluded:

Nothing is a surer proof to me that climate enters very much into our pleasures of association & recollection & exercises a decided influence over our imagination, than the effects produced on my feelings by a bright southern day, whether it comes to me in a dream, or, more rarely still, when a few of the most adventurous of these birds of passage straggles so far north as Boston.6

Her grandfather, who had described dreams as mere “incoherencies” and had shunned the Christian concept of miracles in any form, famously devoted his nights to quiet reading and denoted the sun as “my almighty physician.” The granddaughter who most took after him—whose style of writing most resembled his—belonged to a generation that partook more of mystery and spirit in religious life, and for whom moonlight mended the mind as well as sunshine did.

Ellen’s was the generation we classify as American Romantics. It has been said that classical and romantic are the systolic and diastolic of time—not mutually exclusive, but complementary. The chambers of the heart need each other, of course; and if we recur to the designation of the classicist’s sun and the romantic’s moon, one rarely eclipses the other completely, and when an eclipse occurs, it does not last.

Let us be clear: the generations were not at odds. Though denied any official connection to the political world her grandfather helped create, Ellen was valued by senior statesmen for her poise and judgment. In that way, she was similar to one of her elder acquaintances, former First Lady Dolley Madison, a Virginia-born Philadelphian who for many years captivated Washingtonians. One of Dolley’s oldest male friends recalled her debut in society: “I well remember it, in all its freshness & beauty, just as we do the delightful dreams which sometimes visit our slumbers, as if to remind us, that there is some thing, in some region better & brighter than any of the scenes in this world of mix’d pleasure and pain.” Dolley had that effect on people, but what a curious comparison he had drawn: the verifiable memory of a teenaged Dolley and the charmed memory that adhered to pleasant dreams.

In 1793, Dolley lost her first husband to the yellow fever epidemic. The following spring she met “the Great Little Madison,” and they married that fall. During their courtship, the wife of a Virginia congressman (who ostensibly heard Madison through boardinghouse walls) girlishly informed Dolley: “At night he Dreams of you and Starts in his Sleep a Calling on you to relieve his Flame.”

Even if the congressman’s wife was toying with Dolley, the Madisons’ forty-two-year marriage was marked by as much passion as fortitude. In October 1805, when her husband was serving as secretary of state under Jefferson and they were temporarily separated, she fretted for him. Trusted messengers carried their letters, and it was by this means that she wrote confidentially: “In my dreams of last night, I saw you in your chamber, unable to move, from riding so far and so fast—I pray that an early letter from you may chase away the painful impression of this vision.” She closed the letter with: “Think of thy wife! who thinks and dreams of thee!” Years later, when, at eighty-five, the fourth president collapsed and died at breakfast, his ever-affectionate widow would respond to a letter of condolence: “I have been as one in a troubled dream since my irreparable loss of him.”7

In 1807, one member of the Jeffersonian circle, the keen-witted troublemaker Thomas Paine, wrote “An Essay on Dream.” It was the last original work that the Revolutionary published in his lifetime, a prefatory piece in advance of a scathing critique of religious dogma. In early 1776, urged on by none other than Dr. Benjamin Rush, he had authored the momentous pamphlet Common Sense, which turned up the heat on an already percolating spirit of rebelliousness. Capitalizing on his fame, Paine went public in the 1790s with his freethinking ideology. The Age of Reason shocked a sizable number of Paine’s former supporters. From then until his death in 1809, he fought off attacks from all who detested his unexpurgated irreligion—which, in reality, fell short of atheism.

His thesis was a recapitulation of the Enlightenment’s optimistic, deistic belief in a godly nature. For many intellectuals, the prophetic books of the Bible belonged to ancient poetry, and natural causes and natural laws made far more sense than inherited understandings of Christian revelations. Reasoning men elevated Isaac Newton above the New Testament. Yet even Unitarians like Rush, whose liberal humanism was much closer to Paine than to conservative Christianity, rejected Paine’s authority to speak on the subject. Once tarred as an atheist, a person was unlikely to lose that label.

Paine’s 1807 essay separated dream narratives from Christian allegory. “In order to understand the nature of dream,” he said, “it is first necessary to understand the composition and decomposition of the human mind.” Relying on an Enlightenment vocabulary, he proposed that in the waking state, the three main faculties of mind—imagination, judgment, and memory—were equally active. But in sleep, he explained, regularity and rationality could not be relied upon.

What he found most curious about the dreaming mind was its ventriloquizing power “to become the agent of every person, character, and thing of which it dreams. It carries on a conversation with several, asks questions, hears answers, gives and receives information, and it acts all these parts itself.” As an unstoppable force in sleep, the faculty of the imagination indulged its wild side, “counterfeiting memory” to the point of confusion: “It dreams of persons it never knew, and talks with them as if it remembered them as old acquaintances. It relates circumstances that never happened, and tells them as if they had happened. It goes to places that never existed, and knows where all the streets and houses are as if it had been there before.” For Paine, the matter was one he could cast in the vocabulary of political systems: sovereignty. In the light of day, dreams obligingly yielded their sovereignty over the mind back to memory.

The oft-spoken comparison to insanity impressed him as it did other thinkers: “It may rationally be said that every person is mad once in twenty-four hours, for were he to act in the day as he dreams in the night he would be confined for a lunatic.” It was, Paine concluded, “absurd” to ponder too closely the meaning of a dream and just as illogical to center one’s religious faith on this odd species of thought.8

Ezra Stiles Ely was pastor of the Third Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia and namesake of the Yale College president and dreamer whom we met a bit earlier. Prominent in his own right, Ely authored Conversations on the Science of the Human Mind a few years after Paine’s death. It was a book on human appetites, organized as a dialogue between a professor and student, and included the following:

Pupil: What is insanity?

Prof: It is a state of mind in which the mental faculties do not operate in a natural manner.

Pupil: What are the most common mental causes of insanity?

Prof: An excessive indulgence of some affection or passion is the most common cause of permanent madness.

This exchange led almost immediately to a teaching moment about dreaming. Not only is the correlation, which we have already seen, worth noting, but the logic is equally fascinating, insofar as it is the one area in which modern science and early American medico-religious thinking are pretty much aligned:

Pupil: Well, Sir, is not dreaming a species of insanity?

Prof: Any mental operation performed while one is asleep is called dreaming. There is some resemblance between the state of an insane person and that of a sleeping person who dreams: still, dreaming is not raving. When one dreams, he does not generally think himself asleep; and when one is insane, he is very prone to think all other men are more mad than himself. In a state of insanity, some of the faculties seem to be dormant, while others perform strange operations: and in sleep the faculties of the dreamer are not all equally active, nor equally consistent in their activity.

Pupil: Do we always dream, when asleep?

Prof: We not always remember what our minds have been doing, when we were asleep; nor can we recollect any considerable portion of our mental actions done while we are awake. That we do not remember to have been at all times conscious of thinking, feeling, willing, and mentally exerting ourselves, when asleep, is therefore no proof that we have not been. . . .9

Reverend Ely would not have wished to align himself with the radical Tom Paine, but in this one respect—the analogous features of dreaming and raving—they are close.

The difference, of course, is that in segueing from dreams into his larger project, Paine insisted that “the belief that Jesus Christ is the son of God, begotten by the holy ghost, a being never heard of before, stands as the story of an old man’s dream.” In making the assertion, he repeated the passage from Matthew in which an angel appeared to Joseph in a dream, instructing him with regard to his wife Mary, “for that which is conceived in her is of the holy ghost.”

Delineating several dreams from holy scripture, Paine lumped all together and lamented that such a system of belief had undone civilization: “This story of dreams has thrown Europe into a dream for more than one thousand years,” he charged. “All the efforts nature, reason, and conscience have made to awaken man from it have been ascribed by priestcraft and superstition to the workings of the devil.” Living through an era of massive change, he admitted having hoped for more; that in unleashing a new spirit of inquiry, the American Revolution would have done away with “this religion of dreams” and moved ahead. But he recognized that more time was needed, because preachers, though educated to know better, “still believed the delusion necessary.” Paine challenged America’s religious leaders, whose hypocrisy was a two-sided coin: “not bold enough to be honest, nor honest enough to be bold.”10

Paine’s posthumous fame remains secure, but his refusal to mince words on the subject of faith marred his reputation in the immediate period after his death. Though a logical extension of Enlightenment thought, his interpretation made many uncomfortable. Indeed, as the century took wing, the thinkers who spoke on behalf of “rational religion,” having been so long in the spotlight, were gradually overtaken by a cohort for whom wonderment over the god in nature led to mysticism and new bursts of evangelical enthusiasm. Paine, like Jefferson, saw in unquestioning religion an enslavement of the mind. That was their issue. In the nineteenth century, it became less of one.

As the generation born after Revolutionary times began to make its mark, it revitalized organized religion. The average person was not prepared to jettison physicians’ thinking that food consumption and physiology explained what was happening in nightly visions. But prophetic possibilities became increasingly attractive.

Reports of extraordinary dreams circulated widely. Ann Lee, British born and with little education, founded the Shaker sect after an angel apprised her of Christ’s second coming. Shakers, like Quakers, were a pacifist sect. Believing sex the root of all evil, their charismatic leader commanded celibacy from her followers in upstate New York and New England. Though Mother Ann Lee died in 1780, by the early decades of the nineteenth century, the group had expanded into the Midwest. An 1816 account of her life and visions emphasized her ability to commune with the dead, identifying them as they swirled around the living.11

Around this time, a thirteen-year-old farmhand in western Massachusetts, the “mulatto boy” Frederick Swan, was studying the Bible when he took sick. He experienced a series of dreams over a period of months—seventeen dreams judged remarkable enough that someone wrote them all down. In one of these, Frederick was led to understand “that if he read the Bible three months, he should be well.” Well with God, that is.

The “mulatto boy” dreams contain raw elements unrelated to their visionary content: “I dreamt I set out to travel with something to sell, and on the road I saw a large white building”; “I set out to go to my mother in a thunderstorm”; “I dreamt I went to the brook, and saw a boat coming towards me with white sails hoisted—I called to my mother to come see it”; “I dreamt of standing at the foot of my bed on crutches”; “I dreamed of being on the road south of our house.”

“South of our house” offers a clear sense of direction, which would not be necessary if the dreams were wholly contrived. The color white, repeated in six of the dreams, was a widely known symbol of purity and part and parcel of religious narrative. (According to the Columbian Magazine, the national colors of red, white, and blue denoted “hardiness and valor,” “purity and innocence,” and “vigilance, perseverance, and justice,” respectively.) The devil, “a man all covered with bells,” made more than one appearance in the “mulatto boy” collection. And in six of the dreams, Frederick mentioned seeing angels. Consider the likelihood that the mass culture Frederick responded to had designated dreams as supernatural phenomena, whose purpose was to bring people to religion. Thus, the young dreamer lumped all unknown sleep figures into the two extreme categories of devils and angels.12

In the more freewheeling environment coming into existence in early nineteenth-century America, the religious and the medical combined in new ways. Samuel L. Mitchill, M.D., was both a professor of medicine at Columbia and a member of Congress from New York. He served in the House of Representatives from 1801 to 1804 and in the U.S. Senate from 1805 to 1809. This overachiever had a well-deserved reputation for pedantry, but his authority was rarely called into question.13

In 1814–1815, retired from politics, Dr. Mitchill took extensive notes on the startling case of one Rachel Baker, a devout Presbyterian until age sixteen, and now, at twenty, a Baptist. Though “little prone to talk,” she had been praying and preaching in her sleep for years. According to Mitchill, she made a habit of turning in around 9:00 p.m. Not long after falling asleep, she experienced a “fit” and spoke audibly (sometimes in a “forcible” tone). Occasionally, she recited verses from the hymns of Isaac Watts.

Clergymen were the first to sit with her in the dark. They posed questions, and she responded from her stupefied state:

Question: “Are you thirsty?”

Answer: “Yes, but not for the water than man drinketh. . . . I long to draw water out of the well of salvation.”

Question: “What is your greatest grief?”

Answer: “That the hand of the Lord is lying heavy upon me, and that he has made me to differ from my brethren and sisters in a strange and unaccountable manner.”

And so forth.

“Her words are poured forth in a fluent, rapid stream,” wrote Mitchill, after observing the patient. “At times she is remarkably animated, and gives point to her sentences by the most expressive emphasis.” As a physician, he studied her pulse and found it “full, equable, and flowing, without tremor, flutter, or intermission.” Nothing that was tried put an end to her unconscious nightly performances. Even bloodletting, “though practised to a degree considerably debilitating, did not break the paroxysm.”

Dr. Mitchill was right about one thing. Rachel Baker was a fit subject for medical study, but not as an example of supernatural communication. People were known to talk in their sleep; the difference with Rachel was that she did so regularly and for several minutes at a spell. “In some of its forms,” the doctor wrote of her condition, “it manifests its nearness to hysteria and catalepsy. It resembles reverie.” He also saw a relationship to somnambulism, or sleepwalking: Dancing around known neurological states, he settled on a mixture of “reverie, somnambulism and dreaming” for his definition for the Rachel Baker phenomenon: “Strictly its name is Somniloquism; at least as far as speaking goes.” His logic was supported by the general belief that memorization of religious teachings came most easily at puberty, “when the female frame acquires additional sensibilities, and undergoes a peculiar revolution.”14

A second treatment of the Rachel Baker case, which again drew upon Dr. Mitchill, included a feature the earlier edition did not: the doctor’s categorization of sleep pathology, or “somnium.”15 Each subcategory within “somnium” had a corresponding Latin classification, amounting to the most developed taxonomy of dreams and sleep disorders known to the early American republic. Under the broad category of “Symptomatic Somnium,” Mitchill listed indigestion, with troublesome dreams; classic nightmares; and “debility” (somnium cum debilitate), in which “desultory traces of memory and imagination” were “presented in a confused and irregular manner” and attended by a “muttering delirium.”

He designated as the “common dream” a “somnium from fresh and vivid occurrences . . . traced to some conversation or occurrence of the day or evening, or to some actual condition of the body.” Calling it a “somnium,” though, classified any dream as a pathological event. The only difference between “common dream” and the rest on his list was that the former could be explained away as a reaction to recent experience, whereas each of the latter exhibited an obvious disordered character.

There was “Somnium from old and forgotten occurrences” (somnium ab obsoletis), which arose “when long lost images are renewed to the memory, and dead friends are brought before us.” (This would be Rush’s notable graveyard dream.) Next, “Somnium of a prospective character,” which occurred “when the dreamer is engaged in seeing funeral processions, and foretelling lugubrious events by a sort of SECOND SIGHT, as it is called.” This was, by another name, the precognitive, or prophetic, dream, which Mitchill latinized as “somnium a prophetia.” He was especially bold in assigning it a hereditary nature: “This disease is symptomatic of a peculiar state of body, running in families, like gout, consumption, and insanity.”

His “somnium a toxico” was the dream produced by opium administered for pain, known for “disturbing the will and exciting strange fancies.” (This would be the dream that a medicated Thomas Jefferson experienced just before he died.) With similar fearlessness, the doctor explained what it meant to be an oracle or seer. “They see so much,” he said with a certain redundancy, that “their sights are termed VISIONS, inasmuch as the eyes are so peculiarly concerned.” The pathology of clairvoyance was in eliciting impressions so strong and vivid as to appear (though they were emphatically not) supernaturally derived.

Finally, Dr. Mitchill provided a timely interpretation of the ill-defined word “reverie.” At the opening of the era of Romantic poetry, it only seems right that someone should have laid claim to a definition. But unlike his delimitation of the above dream types, Mitchill found reverie to be “idiopathic,” of no obvious cause: “the internal senses are so engaged that there is no knowledge, or but an imperfect one, of the passing external events, constituting what is termed REVERIE; where fanciful traces of thought are indulged at considerable length.” The word means pretty much the same thing to us: a self-directed indulgence.16

We perceive reverie today as a brief respite from our customary focus on ever-present reality, momentary suspension of the will to notice our immediate surroundings. It is an act of summoning memory for no greater end than to find a fleeting harmony. Not every thought has to be concentrated. In the shadows of awareness lies unknown pleasure, even insight.

The modern understanding of “reverie” was about to take hold, and it marked a subtle but important difference between Mitchill’s and the rising generation. Where intellectual powers were suspended, the early American medical professor saw a lapse, a decline in condition. He could never luxuriate in reverie. For budding Romantics, though, it was effectively a new human endowment being discovered. Over the next several decades, Americans would open themselves to internal experiences their parents had shied from. They did not abandon the duty to uphold self-control; they transformed the emotional environment by privileging the role of imagination. A literary revolution was under way. In terms of the culture of the dream, it meant enriching the meaning of everyday life, embracing as positive certain of the phenomena Dr. Mitchill labeled “somnia,” or disorders.

Every generation has its eccentrics. In the post-Revolutionary period, one of these was named Jonathan Plummer. He was an itinerant peddler and a man of little consequence except in his own mind. Before he died, he claimed in an autobiographical publication that God spoke to him in his dreams. He wrote to inform others that it was possible to train oneself to access the divine in this manner. The night preceding his acquisition of a copyright certificate, Plummer said, he had “a very remarkable dream” and heard the words, “Your noble fame, shall reach the sky!!!” Another dream instructed him to drink chamomile tea; yet another directed him to consume a red liquid (he naturally determined that the Lord meant it to be wine). Poet as well as prophet, Plummer could not understand his inability to find love and, just to set the record straight, pronounced himself “no hermaphrodite”—meaning that he was not incapable of pleasing a woman. After unsuccessfully warning others of the approaching Final Judgment, the unrequited, self-described “old bachelor” officially ended his literary career by starving himself to death in the fall of 1819.17

Now meet Eliza Way Champlain of New London, Connecticut, and New York City, a watercolor painter and the daughter and niece of accomplished painters. She was born in 1797 and lived to the ripe age of eighty-nine. When Eliza arrived, her mother, Betsy, was twenty-three and already caring for one baby. Eliza was the second of four children, then, the rest boys. But because the eldest, George, turned out to be reckless, Eliza was the family’s model citizen as she embarked upon adulthood. Her mother’s older sister, the never-married Mary Way, moved to the big city when Eliza was fourteen, establishing herself as a drawing instructor as well as portraitist. In 1820, the year Eliza’s father, a shipping merchant, died, Mary went blind and was forced to return to New London to live with the family. Two years later, at twenty-five and still single, Eliza followed in Aunt Mary’s footsteps and found herself a place to rent in lower Manhattan.

Eliza’s watercolors are inspired and delicate and her familiar letters clearly the product of a high-spirited imagination. One that preceded her move to New York so delighted friends of the family that it prompted the following commentary: “Letters from Eliza, full of fun and nonsense, . . . are in high demand and much approved if laughing is a mark of approbation.” Not long after Aunt Mary returned to the family and exchanged places with Eliza, she and her niece were writing self-revealingly and arguing affectionately. On the subject of Eliza’s ostensibly plain features, preference for simplicity of dress, and stubborn individuality, Mary charged: “Indeed it appears pretty evident, there is no Doublet and Hose [i.e., opulent Shakespearean garb] in your disposition and more is the pity. You say Fortune has kindly spread a strengthening plaster for your Pericranium to supply the deficiencies of Nature. I say success to the application, but. . . .” The two women, one an old maid, the other, apparently, an old maid in waiting, did not always agree, but they were alike in spirit.

In the same letter, Aunt Mary shared a dream. “I have past many a sleepless night in anticipated pleasure, and when I slept, my dreams were all about it. The other night I heard the voice of Mrs. Fitch [her absent, not deceased, friend] as plain as I ever heard it in my life, I heard her say, ‘If I was a Widow, and had no Family, I would go too.’ I thought much of her and of my dream, if it was a dream, but to me it appeared reality.”

It is not so much the substance of the dream, which made complete sense only to the correspondents, but the dreamer’s attitude that tells us something important. The blind Aunt Mary placed emotional value on the words of Mrs. Fitch as they came through her sleeping mind. The mere appearance of Mrs. Fitch was not something worth her comment, because known individuals appear to us in dreams, and we accept this as a common feature, if not function, of the dream. Anna Fitch lived in lower Manhattan—she was formerly Mary’s neighbor and now Eliza’s. What Mary needed to do, for her own comfort, was to rationalize what her dream said to her about the death(s) she had conjured.

“Now you must know,” she went on, “we are great dreamers, here in Yankee town, and we have great faith in dreams also, and in the interpretation thereof. So I determined to interpret my dream in the manner most agreeable to myself, which is in the words of Brutus ‘Not that I loved Caesar less, but that I loved Rome more.’”

It sounds like in dreaming Mary wasn’t fantasizing the death of Mrs. Fitch’s attorney husband, or projecting a fateful decision onto Mrs. Fitch herself, but only expressing the desire to have the flesh-and-blood Mrs. Fitch come and keep her company in New London. Eliza’s aunt goes on to say, in fact, that, in interpreting her dreams, “I prefer a more plain and simple exposition. . . . I would then enjoy the company of those I most love and value.”18

The salutation Eliza used most often in her letters to the painter sisters was “Dear Mother & Co.” On at least one occasion, though, it was the especially charming “Dear Sisters of the brush.” In October 1822, still building her career in the city and concerned in not having heard from home in two months, she wrote nervously:

Although I am not at all superstitious, a dream that I had last night may perhaps be the cause of my writing to day. I fancied myself in a house opposite to the one in which you live, and that I saw a coffin brought out from your house and placed in a hearse that stood waiting at the door. It moved slowly round the corner and proceeded to the grave yard followed by more people than I thought New London contained. As the last of the train disappeared from my view I beheld the air filled with angels each having a golden trumpet in their hand and their perfectly “symmetrical” forms enveloped in a robe of the most transparent texture. I can give you no idea of the grandure and sublimity of the scene, or of my sensations while gazing on it.

This was one of those dreams Dr. Mitchill classified as “Somnium of a prospective character,” complete with the funeral procession he had outlined; it was not one of those didactic angel dreams that found their way into religious publications, because this dream bore no meaning for the larger world. Indeed, Eliza said about her vision that she felt “loath” to return with the trumpet-bearing beings to the “celestial regions” where they resided. The troubled dreamer just wanted to be reassured, as she awaited a letter, that no loved one in New London was then being mourned.19

Her mother wrote back confirming that everyone was fine. A commentary on Eliza’s dreaming habit followed, showing that, like her sister Mary, Betsy Way Champlain took an interest in the active life of the nocturnal mind:

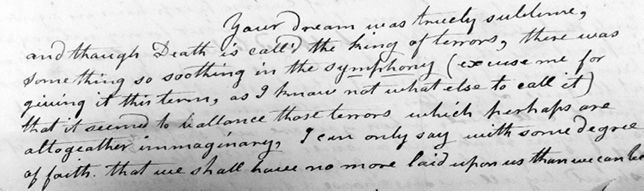

Your dream was truely sublime, and though Death is call’d the king of terrors, there was something so soothing in the symphony (excuse me for giving it this term, as I know not what else to call it) that it seemed to ballance those terrors which perhaps are altogeather immaginary. I can only say with some degree of faith that we shall have no more laid upon us than we can bear.

“Some degree of faith” gives us a fair idea of the muted religiosity Eliza had likely experienced growing up—this was not a strictly pious family. Betsy’s choice of the word “symphony” in the context of discussing her daughter’s troubled dream is also faintly suggestive, even though the trumpets were not sounding for Eliza, and her dream, as laid out, was visual and not auditory in character. From the same source, after a few months had passed, came this maternal piece of advice:

I am of the opinion that your Dreams proceed only from your Dissipation as you term it. Late sitting up has a tendency to weaken the system [and] often causes unpleasant dreams, this I know from experience, and perhaps there is nothing will make a person grow old faster. Mary bid me say to you that there is no meaning in any dream . . . and you may throw all your Devil ones to the wind.20

The combined resolve of Betsy and Mary seems hardly different from what Dr. Rush might have prescribed: a peaceful evening without undue exertion so as to yield pleasant dreams. We do not know what “dissipation” Eliza had referred to, because her letter is missing. But it is clear from the tenor of her earlier ones that “dissipation” was a relative term, an exaggeration for effect. She read a good bit of fiction and had a healthy fantasy life. She invested considerable energy in her painting. She wrote with fervor. But that appears to be the extent of her dissipation. At worst, she may have participated in social activities that kept her out late. Whatever it was, it was bringing on the occasional nightmare.

At a dinner party in the city, Miss Champlain, the young, sociable painting teacher, had occasion to meet the former governor of Ohio, Ethan Allen Brown. A New York–educated lawyer who had migrated west, Brown was an attractive man, an eligible bachelor. Blessed with both looks and intellect, he had, in addition, the distinct honor of being born on the same day as the nation he served: July 4, 1776. In May 1825, when he and twenty-eight-year-old Eliza met in Manhattan, Brown was fourteen months shy of fifty.

“Since my residence in New York,” she wrote “Mother & Company,” “I have not been so charmed with the conversation of any gentleman as his. . . . His person is tall and commanding, his face tho’ not strikingly beautiful is nevertheless of the first order of fine faces and there is a fire in the quick fascinating rays of his fine eyes.” After continuing on at length about the governor’s attributes, she dissected his conversation, which came to encompass the subject of males and females and their respective places in the social order: “He insinuated that woman, lovely woman was an enigma after all.”

This was treated as a taunt by one female of their party, none other than the irrepressible Anna Fitch of Aunt Mary’s dream, who advocated with intensity for the political rights of women. Interpreting the moment for Betsy and Mary, Eliza noted of Ethan Brown “an ill suppressed smile on his expressive countenance at the soreness she exhibited on the subject on which she feels most sore.” Betraying her own comfort with the norms of the day, Eliza wrote critically of her neighbor: “I assure you she fought like an Amazon—she fought with a zeal worthy of a greater cause at least.”

Eliza did not understand why some women became “almost wretched because Dame Nature chose to call them the weaker vessel.” For her part, “Nature in making me woman has offended me less than in anything else she did when mixing up my composition, for in truth tis a queer medley—she intended me to get along through life by my own exertions.” Personable and at no loss for friends in the big city, she was able to support herself as a single woman and did not feel oppressed. Governor Brown, meanwhile, fulfilled Eliza’s expectations of masculine self-confidence. Unprovoked by the feminist Fitch, he was “all humility and submission while the storm was venting its rage.” It is important to note, however, that even as she bowed to woman’s designated social role, Eliza rejected the medicalized assumption about a female imagination naturally inclined to emotional extremes.

In her late twenties, she was already an unusual statistic among eligible women. She was considered too old not to have found a proper husband. Perhaps it was that her favorite aunt, self-sufficient until she lost her sight, had led a fulfilling life without a husband, which altered the timetable for Eliza. It was more than all right for Ethan Allen Brown to remain unmarried—it certainly did no harm to his public image. A friend and fellow governor joked with him: “Have you not violated the great command increase and multiply? Have you not bedewed the pillows of love-sick damsels with tears. . . !” And he joked back that he would rather “scatter” than “concentrate” his manly seed.21

It becomes clear in her letters that Eliza Champlain was hoping to find a mate. On some level, the elusive bachelor Brown charmed her. But instead of an older man, she ended up with someone two years her junior. It was right around this time, in fact, that she met Edward Riley, a musical instrument craftsman. In dreaming of an easy camaraderie, though, she was about to find life complicated. Her mother suddenly died, and Eliza was obliged to return to New London to help care for Mary. This made for a prolonged courtship.

The first extant letter from Eliza, in New London, to her fiancé in Manhattan was penned in February 1826 and bore the salutation “my dear Edward.” He had thought, on the basis of something she had said, that this woman of poise and maturity might have been belittling him for his “timidity,” or unmanly bearing. So she wrote back to reassure him that her uncensored thoughts did not indicate disappointment in him, let alone a desire on her part to take charge: “I could no more love an effeminate man than you could love a masculine girl. They are both out of Character—and of course disgusting.”

Eliza painted a miniature of Edward, to have and gaze at while they were apart. Despite the loss of her mother, much of the courtship correspondence reveals her to be as winsome as she had been in years past, resorting to light banter and exhibiting good humor. He wanted her to learn a musical instrument, convinced that one species of art promised good results in every other. But she demurred: “You know I told you I certainly never could learn any thing by rule—I was not born by rule and I know I never should have Painted decently if the rules of Painting had been stuffed into my skull.” And then she bade him bring his “pretty face” to New London. Threatening to box his ears—a thinly disguised sexual come-on—she admitted: “I dream of you often—sometimes my dreams are very laughable—at others more grave—tho’ never at all gloomy.” And then she concluded her mostly playful letter with an earnest “Adieu love I am yours Eliza.”22

That spring, the couple wrote constantly on subjects far and wide. Eliza said she objected to the British tendency to “mask strong feelings under appearance of coldness.” She understood what was expected of a woman of her generation: a delicate blend of liveliness and reserve. “I know if I should attempt to conceal any feelings on some occasions I could not succeed,” she wrote. “I am not English and have not yet learnt [i.e., taught] my looks to contradict my feelings.” Honest and unafraid, she prized openness in a way we would not have seen in the preceding generation. To take the exceptionally forthcoming Benjamin’s Rush’s courtship letters as a counterpoint, we find the following: “I am now standing on an eminence. The married life stands before, and the single life behind me. My dearest Julia is the principal figure in the groupe of objects which surround me.”

The remainder of his courtship letters adopt a similarly restrained tone. In the Revolutionary of 1775, we encounter hardly any self-reflection. “I admire you for your accomplishments—but I love you chiefly for your virtues” is an axiom, not a revelation. He mentions “the flame of love in my breast,” but he does not describe it emotionally. Even a warm sign-off of “Adieu my dearest girl. My whole soul consents when I add that I am your wholly” does not escape convention. We find a good deal more of the inner man in Rush’s dreams than in his love letters.23

In the writings of young couples in 1826, the imagination is readily engaged. We find Eliza continuing to indulge in dream lore. After Aunt Mary and her brother—Eliza’s uncle—attend a New London wedding in April of that year, she writes again to Edward:

Uncle sent me up some of the cake (as I had retired) with a charge to put it under my pillow in order to dream of you___ Accordingly I placed it there–and instead of your pretty face presenting itself in my dreams I was annoy’d all night by no less a personage than our beautiful Cat Malt. The next morning when I went down I was obliged to give an account of my dreams—Uncle Way laughed hartily at my beau—but I did not care–and determined to dream on the cake again—and again—as the rule is three nights—the next night (which was last night) I made a second attempt to get sight of you—and was prevented exactly as the first by that rascally Cat presenting herself, and no one else—to night is the last and if I dream of her again I will shoot her tomorrow.24

Nothing so perfectly captures Eliza’s irrepressible humor as her offhanded engagement with rank superstition. She knows better than to indulge the fantasy, but a penchant for clowning around makes her go through with the exercise. It provides her with a great visual punch line, too: her comic resolution to shoot the cat.

We have already seen how dreaming of a coffin, mourners, and an angel once caused Eliza a slight twinge, if not quite credible alarm. Shortly after this lighter engagement with dreams, Eliza and Aunt Mary found themselves ruminating about the subject once again—this time while under the same roof. We can read about it because they brought Edward Riley into the conversation.

The dreams, in this instance, were not their own. They were the drug-induced dreams of Thomas De Quincey (1785–1859), who, in 1822, shocked and titillated readers in England and America with his Confessions of an English Opium-Eater. Eliza read the book aloud to Mary, and Edward read it independently. “The Opium Eater is certainly very interesting,” Eliza wrote to her betrothed, “but I think I never felt more melancholy than when I had finished it—and as I do not fancy melancholy—the book is not altogether to my taste. Aunt Mary was delighted with it.” As was Mrs. Fitch, for that matter.25

De Quincey’s Confessions, a testament to the enticements and torments of addiction, stands as the most dream-intensive piece of literature in this era. At a very young age, the author lost his father to consumption (tuberculosis) and eventually came to believe that regular use of laudanum—taking a liquid concoction of opium and alcohol—staved off an inherited tendency to the generally fatal disease. Barely five feet tall and sickly, De Quincey was haunted, too, by the early death of a favorite sister. He was defiant toward his devout, emotionally unavailable mother and the guardians appointed to oversee his inheritance.

The books that appealed to his budding imagination were Samuel Johnson’s Rasselas (1759) and Mungo Park’s Travels in the Interior of Africa (1799), both of which involved elusive quests and mysteries of the mind. Despite having been tapped as a promising scholar of Greek and Latin, De Quincey quit school to test his mettle, and with little to support his chosen lifestyle, he formed a particular attachment to a teenage prostitute named Ann with whom he lived for a time in an unfurnished house in London. His impulsiveness, despondency, passion for poetry and literature, and the tumultuous dreams that he experienced even before his addiction began made De Quincey an ideal carrier of the Romantic word.26

In the Confessions, writing as a rehabilitated addict (in fact, though, De Quincey never completely kicked the habit), he dates his earliest acquaintance with the drug to the year 1804 and an incapacitating toothache. During his initial courtship with the medicinal extract, he found that it composed him while encouraging “the great light of the majestic intellect.” He would go to the opera house and revel in all that his ears took in: “Opium, by greatly increasing the activity of the mind generally, increases, of necessity, that particular mode of its activity by which we are able to construct out of the raw material of organic sound an elaborate intellectual pleasure.”27

When, in 1813, he began using opium daily, his nights became increasingly anguished; his happiness yielded to “an Iliad of woes.” A turbaned Malay with “small, fierce, restless eyes” who had come to his door one day became, in his dreams, a symbol of all he feared in the Asiatic psyche. For whatever reason, the Malay had caught hold of his passive mind, taking him to a part of the world where humanity was “a weed.” Again and again made captive in this cruel, foreign place, De Quincey was forced to live among snakes and crocodiles. He hated the Asiatic with all the patrician intolerance and Tory xenophobia he could muster. By now married and the father of two, he often found that he could be liberated from the “hideous reptile” living in his mind only when his young children woke him at noon with their happy, innocent voices. His frightened wife implored him to stop taking the drug, and he tried to temper his dreams by conversing with her and the little ones just before bed, “hoping thus to derive an influence from what affected me externally into my internal world of shadows.”

In 1819, still unable to resist opium but apparently able to sleep securely again, he had a powerful dream in which he reencountered the prostitute Ann, whom he had long since despaired of ever finding alive. In the dream, he believed it was Easter Sunday, and he was standing before the cottage where he now lived with his family, but in the distance loomed a mountain range of Alpine heights. Then, turning back to his garden gate, he beheld the domes of a Jerusalem-like city, and there sat Ann. “So then I have found you at last,” he said. She would not answer. She looked the same age as before and even more beautiful. The scene dissolved, and they were back on the lamp-lit streets in Oxford where they had walked side by side. He was young again.

To demonstrate the immoderate power of the dream, De Quincey relates one more, which took place in 1820, a short time before he penned his Confessions. It is a dream filled with sound, and louder than all the trumpets we have encountered before. Here is what De Quincey says of it: “The dream commenced with a music which now I often heard in dreams—a music of preparation and of awakening suspense; a music like the opening of the Coronation Anthem [composed by George Friedrich Handel for King George II, in 1727], and which, like that, gave the feeling of a vast march—of infinite cavalcades filing off—and the tread of innumerable armies.” This was not a martial moment, but “a day of crisis and of final hope for human nature, then suffering some mysterious eclipse, and labouring in some dread extremity.” Great drama was under way, another Last Judgment fantasy, and it came with an overpowering sound track.

De Quincey had no firm idea what was at stake. “I, as is usual in dreams (where, of necessity, we make ourselves central to every movement), had the power, and yet had not the power, to decide it.” In the theater where our dreams are staged, whether or not an orchestra plays, the director—who is also the main actor—never knows how the scene will play out.

After this dream, De Quincey cannot carry on as before: “And I awoke in struggles, and cried aloud—‘I will sleep no more!’” Now, as he finally begins to wean himself off his opium habit, the reader is given the moral of the story: do not do as I have done. As obvious as the moral is, the author confides that such scenes, once ingrained, never disappear entirely: “One memorial of my former condition still remains: my dreams are not yet perfectly calm: the dread swell and agitation of the storm have not wholly subsided.”28

When Eliza Champlain wrote to her fiancé Edward about De Quincy’s book, though its melancholy strains failed to impress her, she called the author “a true philosopher.” Aware that Edward was predisposed to like the book, she lightly praised De Quincey for his originality of style—“this I don’t dislike”—while insisting that she could not bear to read it a second time. Separately to Mrs. Fitch, she tried humor: “Aunt Mary is quite delighted with the Opium Eater (what a horrid title the book has). You would fancy her under the influence of Opium while she was listening.”29

Two Romantic poets directed De Quincey’s writing career: William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. As an Oxford student, De Quincey wrote a letter to the former, begging for his attention, and was rewarded, at twenty-two, by becoming a virtual member of the Wordsworth family. By then, he had successfully conspired to meet his other hero, Coleridge. According to De Quincey’s most recent biographer, knowing how much Coleridge needed opium (“and that he had written and spoken great things while on it”), De Quincey may have upped his own dosage, dragging him into worse nightmares. However, even without an opium habit, he was accustomed to brooding trances, in no small measure due to the intensity of his other habit—reading. The same might be said for dreamers at large before the electronic age, dramatically so in this age of expansive poets. Evening reading fed potent sleep visions.30

Educated Americans read Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Lord Byron with a passionate engagement most moderns can no longer appreciate. The Romantic poets spoke to the human condition as few could. Coleridge is especially pertinent to the discussion, because of his own admitted obsession with opiated dreams. Most famously (and questionably), he revealed publicly in 1816 that his masterpiece, “Kubla Khan,” had come to him in a dream. The poet was convinced of the prophetic potential of “visions of the night,” in which powers emerge that do not exist in any “day-dream of philosophy”; this was what Hamlet meant when he said to his closest comrade, “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, / Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

Artists, poets, and inventors have long insisted that some of their best productions came to them either in dreams or in some other form of “effortless thinking”; they take the imaginative segments and complete their plots. In Coleridge’s case, the poet was unable to let go of the subject of dreams at any time in his life. It continually perplexed him that the sleeping mind accepted every absurd distortion of waking life, such as the transformation of a known person into someone with impossible features or altered shape.

Depending on whose work one read, dreams were either a diagnostic tool or a disease; they meant something, or they meant nothing. Coleridge’s notebooks show that he read the history, the medical literature. He did not deny physiological explanations of the sort to which Drs. Rush and Mitchill and their British counterparts subscribed. He believed many if not most dreams to be connected to “motions of the blood and nerves” or “oppressive air” in the stomach and bowels—manifestations of pain somewhere within the physical body. The “fevered imagination” the physicians kept bringing up connected his dark creativity to organic morbidity.

He took an interest in the Rachel Baker case, unwilling to reject the possibility that the young woman did, in fact, communicate with a divine entity when she sermonized from an unconscious state. And like Eliza Champlain, whose coffin dream prompted an urgent letter home, Coleridge wrote about his concerns for the health of a Mrs. Barlow after repeatedly dreaming about her—it all seemed ominous to him.31

Poets were the movie stars of the nineteenth century. As with celebrities today, the lives of the Romantic poets were intertwined. Coleridge published “Kubla Khan,” with his prefatory explanation of its dream origin, at Lord Byron’s instigation. In July 1816, the same year “Kubla Khan” was published, Byron wrote his deeply expressive poem “The Dream,” from which this book’s epigraph is drawn. It begins, “Our life is two-fold: Sleep hath its own world,” and goes on at length to narrate a night’s tale of two whose promise of enduring love is diverted and finally crushed.

Byron’s dream may be an invention, but its structure resembles that of a raw dream. He chooses to begin six consecutive sections with the line “A change came over the spirit of my dream.” (As we shall learn, Abraham Lincoln, a believer in the power of dreams, counted this poem as one of his favorites.) Summering in Switzerland with his poet friend Percy Bysshe Shelley, Byron composed the gloomy “Darkness.” It opens with the line, “I had a dream, which was not all a dream,” and proceeds to envision the extinction of suns, with desperate men on an icy earth setting forests on fire in a last hope to save the light. It is a beautifully wrought poem for a people who lived with death and could not govern their dreams.32

After Shelley’s drowning death in July 1822, at the age of thirty, his disconsolate young widow told two female friends that she saw him in her dreams on a regular basis. A diary entry in February 1823 attests to her misery: “I was reading–-I heard a voice say ‘Mary’—‘It is Shelley’ I thought-–the revulsion was of agony—Never more shall I hear his beloved voice.” And a week later, this diary entry: “Visit me in my dreams tonight, my loved Shelley.” The next year, it was Byron who died, at thirty-six, succumbing to a fever in Greece, where he had offered his services to a band of revolutionaries.33

The rakish poet-adventurer Byron was not always treated kindly in the American press. Eliza Champlain would have read in the New-London Gazette a defense of candidate John Quincy Adams’s suitability for the presidency that distinguished his “restrained” nature from the “exceedingly alarming and dangerous” passions of “Byron and Buonaparte”—certainly an unflattering pairing. In 1825, advertising an ethereal Byron, the New-York Mirror printed a fantasy piece, “Literary Thermometer: A Dream.” In it, an angel guided a dreaming “son of the earth” through scenes that eventually led him to a funeral procession: “It was the remains of Lord Byron, attended only by the nine muses.” Americans found in Byron a larger-than-life dreamer, a veritable philosopher of dreaming. His open excesses—a profligate life made public—imitated the unrestrained, uncensored character of a dream world.34

As for the artist Eliza and the musical instrument manufacturer Edward, the couple married in 1826 and settled in Orange, New Jersey. She accepted painting commissions up to her wedding day, and he continued the family business. As a dream aficionado, she rendered her final decision on De Quincey’s opium dreams: chilling, indeed, but not as powerful as what Shakespeare was able to dramatize. “I think Clarence’s dream is ten thousand times more dreadful than any of his,” she said of Richard III. “That dream is too well painted—for I died in reading it.”35

She was referring to the suspenseful moment in Act I, Scene 4, as Clarence, brother to the murderous king, tells his jailer his dream of drowning:

O Lord! methought what pain it was to drown!

What dreadful noise of waters in mine ears!

What sights of ugly death within mine eyes!

At the bottom of the sea, jewels sat in skulls where eyes once were, “And mock’d the dead bones that lay scatt’red by.” Entering the “kingdom of perpetual night,” Shakespeare’s dreamer remains captive of his dark imagination:

A shadow like an angel, with bright hair

Dabbled in blood, and he shrieked aloud. . . .

With the Furies of his dream still howling in his ears, Clarence tells of the awful, clamorous vision foreshadowing his fate. Eliza was right: no matter the depth of De Quincey’s fear of Asiatics and crocodiles, it would be next to impossible for the opium-eater to shock the bard.

With his keen psychology and close attention to character, Shakespeare was a school unto himself. For his part, Byron dazzled in print. De Quincey constructed a long and successful writing career on the elevated reputation of his confessional book. Dreamers found support, and adopted the vitality they discovered, in the ardent imaginations of their literary models.

Charity Bryant loved women. At thirty, she met Sylvia Drake, eight years younger, and for the next forty-four years, they lived together—married in all but a legal sense. Until Charity’s death at mid-century, they were accepted as a couple by the Vermont community in which they lived, leading active lives in the church and co-owning a tailoring business. Charity’s affectionate nephew, the poet and newspaper editor William Cullen Bryant, went on to publish a story about their remarkable life together.

Before she met Sylvia, though, Charity was involved with a woman named Lydia Richards. After their physical relationship ended, they remained close friends. On two occasions, years apart, Lydia told Charity that she had appeared to her in a dream. In the first, she wrote: “I was seated in the west room at my Father’s, near the bed, when you approach’d me with a radiance and sweet expression in your eyes which made too deep an impression on my mind to be dispell’d or erased by the beams of the morning.” The second dream was more mysterious: “I was parting with you and after I had turn’d to leave you, thot of something further I wish’d to say and turn’d back, but seeing your face hid I again turn’d to leave you—but feeling unwilling to go without saying what I wished. . . .” The double take and indecision repeated, until at last Charity let her face be seen. Opening her eyes, she displayed tears, and then, in Lydia’s words, she “look’d upon me with a smile which I return’d.”36

A far less noble dream with sexual implications came to the attention of John Wurts, a prominent attorney in Philadelphia. He had served in the state legislature and was shortly to win election to Congress. In the early months of 1823, he received a confidential letter from an acquaintance, Roberts Vaux, a philanthropist who carried weight in the City of Brotherly Love. One of Vaux’s chief interests was providing support to schools that accepted students from poor families. He served as president of the Board of Controllers for Public Schools and was personally involved in shaping school curricula.

It is understandable, then, that he would take a personal interest in the case of a teacher named Seixas, charged with molesting the young teenage girls who sat in his classroom. Somehow, the allegations against him had been kept out of the newspapers. Vaux did not want to see the matter swept under the rug and figured if Wurts knew what was going on in private meetings he might be able to do something. Seixas had a capable attorney working for him, and though the client looked guilty based on the testimony of several individuals, it was the unusual means by which Seixas was first fingered that gave the defense confidence it would win at trial.

According to Vaux, “it appears that the suspicion of improper conduct first originated from the circumstance of the mother of Letitia Ford having been disturbed by a dream, which she interpreted to augur something unfortunate to her daughter who was at that time under the care of Mr. Seixas.” Based simply on her dream, Mrs. Ford presented her suspicions to a member of the school board, and “unknown to Mr. Seixas a private and strict examination into his conduct was instituted.” Without taking the teacher’s side, Vaux was incredulous: Who would believe that “any society of tolerably respectable individuals could play such a disgraceful farce before the community as that of instituting a solemn investigation on the ground of an old woman’s dream”?

Pubescent middle-class girls were meant to be protected from masculine vulgarity in whatever form it took. Yet misogyny was also alive and well in nineteenth-century America, evidenced in tavern culture and in the kind of humor newspapers regularly published. A Philadelphia magazine of this era featured an essay on dreams, with a moral directed at women: “Females are most apt to put faith in dreams,” it read. “Whether this be owing to a peculiar conformation of the brain [producing visionary thoughts]; or whether from the more secluded and domestic habits of women, they have more leisure to remember and reflect on the thoughts that intrude upon the sleeping hours, we shall not attempt to decide.” Deemed easily susceptible to outside forces, weaker in critical apprehension, and, as a rule, more easily impressed than men, females were reckoned “naturally” prone to superstitious suggestion: “The belief in dreams is often strengthened and confirmed by those catch-penny publications, entitled dream books. . . . The most absurd explanations are set down as undeniable truth.” This, apparently, is the tradition Roberts Vaux had in mind when he expressed incredulity that Mrs. Ford was actually being taken seriously.

The committee that evaluated the board’s report voted that “the Dream of Letitia Ford’s mother was utterly ridiculous,” and that the investigation would proceed without paying any mind to the alleged victim’s mother. By now, however, her claim of special sight was common knowledge, and the case could hardly be separated from the accusatory dream that fed it. Two key witnesses to the teacher’s behavior, Letitia Ford and her classmate Catharine Hartman, stated that Seixas had been in their bedroom at night, yet they did not charge him with having “hugged or kissed” either of them. Someone else said he was seen “taking hold of the legs” of both, and for Vaux that was serious enough. When the “Matron” of the dormitory was apprised of this, she put bolts and bars on the girls’ door to prevent further intrusion.

The statements of the girls were at this point “uncorroborated,” according to the report Vaux cited in his letter to Wurts. Yet Seixas had refocused the attention of those like Vaux when he put his foot in his mouth—or, rather, his hands where they did not belong. “Uncorroborated!” Vaux expostulated. “He said he felt the girls heads.” More students were coming forward, all commenting on the man’s active hands: “Some of the girls say he put his hands under the clothes & felt their bodies.” A teenage boy who did odd jobs around the school said he saw Seixas “taking gross liberties . . . , that when the girls were setting at their writing desks would put his arms over their shoulders and feels their bosoms & thighs.”

Letitia Ford’s mother had had a dream. Her sixth sense, or whatever it was, was right. But a dream only delegitimized what was otherwise a valid cause. Vaux made clear that he did not wish to get involved. Wurts may have felt the same, insofar as Seixas was known to have vocal supporters. In the end, given that no publicity ensued, the libidinous teacher appears to have escaped punishment.37

From the birth of the republic through the mid-1820s, the majority of recorded dreams were relatively uncomplicated and tended to focus on real-life concerns. Elizabeth Drinker, who saw a great deal of death and described it in her diaries, watched the houseguest in her dream choke on pork. Dolley Madison, who doted on her frail husband, saw him in an enclosed space, unable to move from “riding so far and so fast.” From modern science, we learn that whatever emotional issue the person is addressing, the dreaming brain searches for contextualizing metaphors.

Even when early Americans were not dreaming of death directly, mortality was never far from the surface of their communications. They dreamt of distant loved ones, imagining them present. Fear of death bridged the days and weeks between letters received. Of this species of dream, Louisa Park’s are probably the most pained and intimate, constituting a detailed record of the odd behavior and uncharacteristic conversation of her long-absent husband each time he visited her in the night.

Here is another of that ilk. Jane Bayard Kirkpatrick of New Brunswick, New Jersey, was fifty-three in 1825 when she had “a sweet vision” of her son Bayard, though he was in South America on business. “I saw him just as he looked in his picture,” she recorded. “I thought I was sitting on the sopha—and he came behind—and leaned his head on my shoulder—and with an expression of tenderness & sensibility uncommon in him said to me ‘dear mother, how happy I am in the persuasion of your love’—I laid my cheek by his—and waked.”

The dream, which she herself described as “vivid,” impelled her to reflect—but not on the science of dreaming. Instead, it was on the wonderful mystery dreams conveyed. She noted that she rarely dreamt of her son, and that the Bayard of her dream was a good deal more expressive of emotion than he was in life. This was especially satisfying to her. She had had less pleasant dreams about him a year and a half earlier, and in one of these pictured him in the middle of a war, “wounded—but not mortally.” So she knew to suspect dream-borne prophecies.

In insisting (or, at least, confiding to her journal) that it was not “weakness or folly” for a person to pay attention to her dreams, Kirkpatrick defied the medical consensus. “We know so little of the spiritual world,” she breathed. “But every one has observed striking coincidences in their feelings with those of absent friends—which could not be accounted for—which seemed some thing more than chance.” She is saying: do not discount spiritual communion, though it be little understood.38

As the nineteenth century advanced, a new pattern began to emerge. Bizarre content was finding its way into dream records that are more varied and unpredictable. The one element that does not disappear, however, is the presence of morbid imagery.

Benjamin Rush was anomalous among those of the Revolutionary generation in his willingness to confront the bizarre in dreams. Perhaps this was because, as a heralded medical expert, he was freer to experiment with his thoughts. Everyone else was convinced by the likes of Dr. Rush that dreams were only to be associated with dangerous thoughts and delusions, excessive sensibility, hypochondria, hysteria, and mental weakness. The many and varied classifications of insanity and the aggressiveness of doctors who thought they understood more than they really did about the human psyche must have weighed on dreamers’ minds and restrained their pens—after all, no one wanted to sound mad.

The bizarreness of dream content (skipping from place to place, people appearing and disappearing, an irrational conflation of images) is something science can explain fairly well now. Bert O. States, a literary theorist who has studied the science of dreams for decades, describes the phenomenon as a “warring process” taking place within the brain when “chaotic ‘bottom-up’ brain-stem activation” comes into contact with “‘top-down’ cortical attempts to make sense of the resulting disorder.” Bizarreness is “the natural consequence of dreams exercising the power of association while the body is ‘off-line.’” Associations collide.39

Citizens in the early years of the republic, rather than stigmatize themselves, limited themselves to acceptable scenarios in dreams that they narrated. They wrote down dreams that they could nearly understand. As the nineteenth century proceeded, the necessity of doing that diminished. Workaday people marveled as the poets captured the wild beauty of dreams and artfully imagined the outer limits of what a dream can say. If regular folks could not express themselves in the language of Byron, Shelley, and Coleridge, they still conveyed in dreams, whether plain or adorned, how they confronted their fears, tried to remain psychologically intact, or simply bore up. The dreamy poet, with his broad appeal, stole the show from the straitlaced medical theorist. Byron was more than a showman performing for a voyeuristic public; he could say what others were loath to say or incapable of reproducing.

It is not easy for us, who generally think of poetry as a less infectious, even obscure, form of literature, to appreciate just how deep an impression Lord Byron made on Americans. History commands us to recognize that selfhood has a history. For earlier generations, poetry was a key part of personal development. It stimulated an assertiveness of belief and a quality of mind that sustained faith in the forces of nature—a faith similar in impact to what words of ancient scripture do for the conventionally religious.

The dreams of the poets posed the central questions we continue to ask ourselves today: Do dreams transmit messages to and from the self? Do they fragment us or help make us whole? Do they pass time, freeze time, or exist outside time? Are they a form of entertainment for the imagination, instruction to the imagination, or both entertainment and instruction?

The faculty of imagination had become, in the 1820s, more than the acknowledged judge of shining beauty and the rival companion of shining reason. Imagination was now upright and affirmative, if still not completely trusted.

“Your dream was truely sublime,” writes Betsy Way Champlain to her daughter Eliza in 1822. Way-Champlain Papers, courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.