Edgeworth Female Seminary (Greensboro, North Carolina) in the mid-1850s, which Clay and May Dillard attended, and where William Lafayette Scott taught.

Clay Dillard Learns a Strange Language

I’m dreaming. O! I’m dreaming.

—Caroline Clay Dillard, 1855

Madaline Edwards loved in vain. Born in 1816 in Sumner County, Tennessee, she came from patriotic stock. Her paternal grandfather, a Virginian, had been an officer in the Revolution. She was educated for a short time at a female academy in Gallatin and had a clear gift for writing. But she never had a chance, having been pressured into marriage by her father when she was only fourteen. The marriage lasted six years and ended unhappily—as did the relationship between her parents. Her father moved to Mobile, Alabama, and remarried. Madaline did not lose contact with him, but neither did he foster emotional stability in her.

By her mid-twenties, she stood five foot seven, with large green eyes. By then she was residing in bustling New Orleans, as the mistress of businessman Charles Bradbury. She lived a few blocks outside the French Quarter, a short walk from the home of her paramour—“Charley,” she called him. When not sitting at home waiting for him to visit her, she was employed (like Eliza Champlain) as a painting teacher. Madaline had an admirer, an unmarried man, whose friendship she valued. But there was no substitution for Charley. For sustenance, she listened to the sermons of Theodore Clapp, a native New Englander who preached at the Congregational Church just off Canal Street.

Before her involvement with Charley began, Madaline was mixed up with one “F.G.” in Vicksburg, Mississippi, who, she wrote, “brought me to my ruin.” Charley would not improve Madaline’s social status either, though she refused to believe that he was stringing her along. And that is what makes her dreams in the sweltering months of 1844 so fraught with pathos.

Charley was heading to Ohio, with his wife, Mary Ann, to escape the heat. He would not return until fall, and Madaline would be unable to get him out of her head. From the diary: May 9, 1844: “The natal day of my beloved C. God grant that he may live to see many, very many more.” May 15: “Oh I have spent a melancholy day. I cannot shake off this feeling that so haunts me and the nearer the departure of C approaches, the worse it gets. I do not see how I can live under his absence. God knows my feelings and he alone. It is worse than death itself.” May 16: “Still unhappy while nature looks so lovely this spring morning. I have just got some work to do for C and will try to shake off my misery in work. Last night I dreamed I saw a lovely infant boy of his and it was his image. I kissed it and loved it, but it was not mine.”1

Her married lover had left town. She occupied herself by reading the likes of Milton’s Paradise Lost and by writing original poems and essays, some of which she was able to publish in respectable local papers. Creativity helped lift her spirits. On the Fourth of July, she listened to the booming guns and recorded her patriotic pride. “I glory in our free born republic, and I venerate the immortal Washington. . . . I had rather boast of being one of America’s humblest daughters than to be an empress or Queen of a Monarchy.”2

The longer Charley was gone, the more she saw him in her generally encouraging dreams. July 8: “Last night I dreamed twice of seeing my dear Charley. One time I thought he filled my lap with gold, which did not make me half so glad as the sight of him.” July 23: “Last night I dreamed such a singular dream of my dear Charley surely it portends a letter.” Justifying a belief that dreams were portents—whatever that “singular dream” was—she noted that the prior night’s had already come partly true when a shipment of “peaches, chickens and other things” arrived from her sister. But in the letter accompanying them, the sister condemned Madaline’s life style, saying flatly: “That man will throw you and your child both on a cold world.”

What child? All signs pointed to it: Madaline was pregnant. More and more dreams followed, reflective of her loneliness and growing desperation. July 24: “Dreamed last night again of dear Charley. Oh that it was reality and not a dream. When will he come.” July 25: “I could sit down and weep half the night but it must not be. Oh such nights are too holy to be spent alone. . . . Dear Charley forget me not. I dreamed again last night I saw him.” On the twenty-seventh, she dreamt of being together with him in his home: “Oh! What extacy was mine last night as I sat by Charley at his own table and when he spoke low to me and said he would be here at dark. How happy I was. His wife seemed much pleased with me and I did not feel unjust towards her but alas the morning dawn dispelled all this happiness and I awoke to sigh and long for the reality.”3

Madaline’s wish-fulfillment dream not only delivered Charley to her, but it also allowed her to replace Mary Ann Bradbury. There are signs throughout the diary that she struggled with jealousy, convinced that no one could love Charley as well as she. To spot the couple walking together, as she occasionally did, frustrated her to no end. Once, when Mary Ann was ill, Madaline gave her lover flowers to take home. The modern editor of her diary has concluded that the gesture was in fact insincere and manipulative.4

The next recorded dream was more chaotic than those preceding. Feeling “on the point of a miscarriage” after a “jolting” carriage ride, she wrote of her friend Buddington, a businessman, originally from New York, who had warned her about Charley’s true nature: “I dreamed last night B rode a horse up and handed me a letter from dear C. I tore it open and it was dated three o’clock night all asleep.” In the letter, Charley told her that he had heard a sermon preached by Mr. Clapp and had decided he would begin to take the sacrament. “I began to cry for I felt it was to Sever our connexion. . . . The letter contained two sheets but just as I read one I awoke, sadly disappointed. Oh will he not write to me? I am almost crazy and sick too.” Ten more days passed. Her feelings were mixed. Dreams remained positive, but reality let her down. August 14: “Last night I dreamed that Mr Clapp presented me with some of the most beautiful flowers I ever saw. . . . No letter [from Charley] yet. My heart is almost wild with despair. . . . He cannot feel for me or he would write.”5

Charley finally wrote to her at the end of August, but it only made things worse and justified the caution urged by her friends. “Recd a letter from C at last and I wish from my soul it had not come for it was as cold as marble and has put me in a state of mind that even his presence could not dissipate. . . . I have wept this day until I am not myself. I cannot get over Charleys coldness to me.” She tried to bring up ethereal thoughts: “I have sat to night with one eye on Venus and the other on Saturn prying into the mysteries of the starry Heavens.” Waiting grimly, impatiently, Madaline wrote an essay at this time, “Tale of Real Life,” which was nearly an autobiography. In it, she surmised: “True there are not so many broken hearts in every day life as fiction represents, but there are more that are every thing but broken, or as Byron truly says ‘though broken still live on.’” These were slightly misquoted lines from the canto of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage published in 1816, a stanza in which the poet describes forms of decay in the natural world to allegorically depict the ways of mourning, of surviving half intact: “The hull drives on, though mast and sail be torn . . . / And thus the heart will break, yet brokenly live on.”6

On October 8, shortly before Charley’s return to New Orleans, Madaline was moved when a male friend sat with her all evening and comforted her. “I wept from many emotions,” she recorded, before turning in for the night. And then, “I . . . dreamed I was dressed in white floating on a wide muddy river and Charley rode on a white horse meeting me on the water and talked with me.” As the anticipation of seeing him built, she had her most extravagant nocturnal vision: “I dreamed the firmament was all on fire and every thing and person in consternation for the day of judgment had arrived. I was with Charley. We clasped each other and fell on our knees. My final word was ‘Thank God we are thus blest in dying together’ and then both prayed but he could say little while eloquence was on my tongue and faith in my heart that all would be well.” Some dreams do not have to be analyzed.

They reunited, but it did not take long for her to figure out that they would not live or die together. When Charley came to visit, he blew hot and cold. At the end of October, as she entered her third trimester of pregnancy, he sat with her one night for four full hours. She wrote in her diary: “I forgot pain and was happy.” She read to him from her original compositions: “He was well pleased and that is all the recompense I ask. We talked of what should be done with my child if it should live and I die.” “My” child, she wrote, curiously enough, not “our” child.7

In a somewhat didactic essay penned for publication a few days later, Madaline found ways to rationalize Charley’s cruelty—by expressing resentment toward the unnamed Mary Ann Bradbury. “I say wives are more to blame for the neglect they and their home receives from the husband than he is,” wrote the mistress. “She has it in her power by a thousand nameless attentions, of winning him to all her wishes.” It was unfair that Mary Ann, who hardly appreciated what she had, had it all. Madaline denied the existence of sisterhood: “Men as husbands are unjustly called fickle.” Here and throughout the piece, she pretended to be a wife, disguising her identity as a kept woman. More to the point, she portrayed herself as a woman who was capable of tremendous love and caring; if she lacked a real hearth, it was no fault of hers.

Next on her schedule was to write out an informal will, in case she died in childbirth. She played it up for Charley: “The time is close at hand that brings me a period of suffering and it may be death also.” To her nameless, illegitimate child, in the same letter: “Oh what a crowd of reflections and agonizing emotions swell to my soul. . . . Oh! what have I not lost?” She feared that Charley would retain no feelings for the child once she was gone and forgotten, so she appealed to him with heightened pathos, asking that the child should be given precious keepsakes: “the little jewelry I wear . . . some of my pencillings and paintings . . . and a few, very few of my clothes.” If a son, she proposed, “I trust it will be like his father, but yet teach it warmer feelings.”8

But there was no child. The pregnancy was all in her mind. Though Madaline must have believed herself with child, her subconscious apparently devised a way to keep her lover attached to her and sustain her faith that they might one day be a real couple.

It was not until the spring of 1845 that Mary Ann Bradbury came to suspect the affair. On April 1, she confronted Madaline on the street, and Madaline maintained her composure. In her diary she wrote proudly: “April fool has not been made of me today.”

She held on as long as she could. Finally, she faced up to the truth. The second stanza of a poem she wrote in March 1846, “To C.,” tells all:

Two years ago, I did not deem

The bliss you had created

Should pass away, a bitter dream

And leave all hope prostrated.

She wrote a second poem that month, since lost, titled “Dream.” And a third, the same year, called “Lines on dreaming that I was again at my Uncles in Tenn[essee] with whom I lived many years and at whose house I was married.”9

Even after the dream ended, Madaline and Charley continued to see each other from time to time. In the first extant letter from him to her, in 1847, he addressed her familiarly as “Mad” and labeled her remarks as to his actions and motives “unkind, unjust, and altogether uncalled for.” Four days after this, apparently in reaction to her reply, he admitted that “it was the Animal that first prompted me to seek an interview with you.” But, he claimed condescendingly, his impulse immediately after was to “raise you up in the scale of human happiness as far as possible.”

In the year of the Gold Rush, 1849, Madaline Edwards left New Orleans for San Francisco, where in the early 1850s she kept a boardinghouse. There she died, possibly of cholera, in the summer of 1854. Charles Bradbury continued on in New Orleans until 1880, when he expired quietly at home at the age of sixty-five.10

Willie and Fannie were not a couple for long either, though under very different conditions. William George Scandlin arrived in Fannie’s hometown of Meadville, Pennsylvania, not far from Pittsburgh, in 1850. He had been born in England in 1828, the youngest of fifteen children, and joined the Royal Navy when he came of age. Then he deserted and came to settle in Boston. With the assistance of the Seaman’s Mission, he was sent to attend the Unitarian Meadville Theological School. There the increasingly devout student met Fannie, and after a short time, he proposed to her. They were married in December 1853. The marriage lasted only through the following April.

He recorded a conversation they had near the end.

Fannie: “My pains are not as severe now but there is nothing of me left. I feel as though I should like to die.”

Willie: “All will be well in time, my dear.”

Then they spoke of Heaven.

“When you go there,” he said, “you must be my Guardian Spirit.”

“O yes Willie—O yes Willie, I will be with & influence you all I can for good.”

His diary for April 28, 1854, the day of her death, reads thus: “O My God My God this is a severe blow. . . . O Dear dear Fannie. My Father forgive the deep agonizing trouble of my overburdened heart. . . . Thou dost all things well but Oh! how deep & mysterious are the workings of they providence. . . . I have been a Husband & am now a Widower all in Four Months & fourteen days!!!”

A week later, struggling with his emotions, he marked the number of days “since the remains of my beloved wife were laid in the cemetery . . . how lonely the spots once so dear and hallowed.” The day after this, he found the portion of her journal she had not destroyed. It was not much, but it would have to be enough. He rummaged around and tried to honor her memory as best he could. He wrote to a girlfriend of Fannie’s who lived elsewhere: “My Dear Friend,” the letter began, “Though I have never enjoyed the privilege & pleasure of an introduction, let me assure you that your name is familiar to my ear.” Its purpose was to tell Mary Hotchkiss what Fannie had requested he convey: “her dying entreaty to all her friends, ‘Meet me in Heaven.’”

On July 15, two and a half months after his young wife’s death, Scandlin beheld a vision of her, and it recharged him:

Last night for the first time I was permitted in my dream to visit my dear dear Fannie—not in her spiritual home but in our earthly home at Meadville. I went into the front parlour. I found her laying on the sofa with Aunt Letitia sitting beside her. Oh what an embrace, what a kiss. It seemed we were just met after a long separation. How cheering is such a dream. Yes I went to visit her. God only knows how soon I may go to visit her.

When it came to a longing for love, dream worlds were not gendered. Willie Scandlin’s visit with his departed wife on the parlor sofa is nearly identical to Louisa Park’s dreams fifty-four years earlier, when her husband was away at sea. In general, when desperate dreamers reaped the intimacy they yearned for, it came not as sudden sparks but as faint glimmers, momentary glances at a better condition than present reality held. Scandlin allowed himself to believe that he had just touched heaven.

Graduating from Meadville Theological School, the young widower returned to Boston, where he served a Unitarian congregation. Eleven months after he saw Fannie in his dream, and scarcely more than a year after her death, Scandlin remarried. Eliza Foster Sprague was herself a young widow. Together they had six children. When the Civil War broke out, he enlisted as a chaplain in the 15th Massachusetts and was captured at Gettysburg. He was released after three months as a prisoner at Libby Prison, in Richmond, surviving the war only to die a few years later at the age of forty-three.11

Caroline Clay Dillard was another who died too young. In her case, the enemy was consumption, the raging lung disease that destroyed untold thousands, if not millions, of lives in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Shortly before she started coughing, breaking out in night sweats, and slowly wasting away, Clay, as friends and family called her, related a dream. It concerned her little nephew Tommy, who had died five years earlier, barely a year old. In her dream, she encountered baby Tommy as a “sweet little cherub boy” who took her by the hand and guided her through a “bright dazzling” dream city.

Despite her early passing, what makes Clay Dillard’s life one worth knowing, and her dream especially poignant, is the dread of a loss of love that infuses the diary she kept in her late teens. After a childhood in Lynchburg, Virginia, she moved to eastern Tennessee with her parents and boarded at the Edgeworth Female Seminary in Greensboro, North Carolina, which she attended along with her older sister, May.

Edgeworth was a special community. It was the only female academy in North Carolina, its students drawn from across the tristate area. The school, founded in 1840, was named for the Irish author Maria Edgeworth. She is barely known anymore, but in the early American republic, “Miss Edgeworth” was far more popular than her English contemporary Jane Austen, the similarly inclined romantic novelist celebrated nowadays as a symbol of the age of gentility. Indeed, to judge by how many times her works were borrowed from the New York Society Library at mid-century, Edgeworth was every bit as popular as James Fenimore Cooper. She wrote morally accented novels about educated women and their emotional trials. She herself was a daddy’s girl when she rose to literary celebrity: it was Practical Education, the popular guide, that first made the Edgeworths, father and daughter, world-famous.

Maria Edgeworth chose to remain unmarried her whole life. She was seventy-three at the time the North Carolina academy was founded, and she died a few years before Clay Dillard’s time there. In 1836, Caroline Lee Hentz of Florence, Alabama, the girls’ school founder whom we met at the beginning of chapter 5, crooned in her diary as she was reading an Edgeworth novel: “Almost divine enchantress! who will ever wear thy mantle when thou art gone.”12

Edgeworth faculty covered writing, grammar, geography, botany, chemistry, and mathematics; piano and guitar lessons were optional. Pupils were obliged to walk around the carriage circle in the front of the sturdy main building twelve times every morning before classes. So wrote Minna Alcott of Albany, New York, who came to teach at Edgeworth because her “constitution” was fragile and her doctor urged her to go where the climate would put less strain on her. A few years before Clay enrolled, Minna wrote home and described the campus, which lay within an oak grove, “luxuriantly planted” with flowering shrubs. She found herself mesmerized by the summer tanager: “its brilliant scarlet plumage makes an exclamation point when glimpsed against the sky.” The “soft, mushy dialect” of Southerners was barely comprehensible to her, as was the constant presence of “Mammies,” who served (and prettied up) the girls. One of her fellow teachers saw prospects differently, protesting the lack of political equality that held women back: “We should impress on our girls what an articulate and modern woman was Maria Edgeworth, and how we, as educated women, must try to improve the lot of women in the world today.”13

That, in brief, was the environment in which Clay Dillard and her older sister May spent the middle years of the 1850s. Minna was still there as a singing teacher and harp instructor when the Dillards attended. May graduated first, so Clay spent her final year at Edgeworth feeling her sister’s absence. Clay wrote of missing her parents and longing to rejoin May.

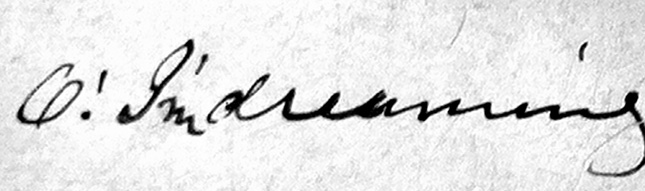

Glued to one of the first few pages of her intact diary is a card, two inches by four inches, on which is penned the signature “W. Lafayette Scott.” Concealed on the reverse of the calling card, pressed against the page, and in Clay’s hand, are the words “I’m dreaming. O! I’m dreaming.” This is where the story of Clay Dillard really begins.14

William Lafayette Scott was her teacher. He had recently graduated from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and came to Edgeworth that year to teach classical studies and mathematics. He was given his middle name, of course, in honor of the Marquis de Lafayette, who, as the last living general of the American Revolution, stole headlines throughout his tour of the twenty-four United States in 1824–1825.

In Clay’s diary, below the calling card that she preserved, are these words:

Here is Mr Scotts card, just as he sent it. . . . I know he thinks me so impolite, but I am afraid some of the girls will find it out and tease me. They are all the time at it now. They say he loves me, but I don’t believe one word of it; though he does look at me so strangely often. What beautiful eyes he has—such a clear, liquid blue. . . . I often hate to move about the school room when Mr Scott is in it for I can feel his eyes on me.

The next day, Clay scratched out a sentiment she would live to regret: “I received the sweetest little card today from Hon’ Thomas Rivers. I never saw him, but I love him dearly. He has completely won my heart. He is in N.C. from Tennessee, and is a beau of Sis May’s so they say. I should feel sad to think Sis May was going to marry any one, but I know Genl Rivers is a noble line [i.e., lion] hearted man and we could entrust to his keeping the happiness of our darling Sister.”

Brigadier General Thomas Rivers, in his late thirties, was an important figure in Tennessee. At that very moment, he was an attorney, a plantation owner, and a U.S. congressman representing the southwestern portion of the state.

Clay’s entry for February 14, Valentine’s Day, is even more emotional: “I received a letter from Sis May telling me she was to be married to Genl Rivers next month. I have cried until my head aches. How can I give her up! And I cannot be there either. I think they might wait until I come home.”

But something else caught her attention on Valentine’s Day: “Prof. Scott told me I was the most mischievous creature he ever saw. He tried to get my consent for him to show one of my compositions.” She received an anonymous valentine. It was a picture of a pair of lovers and was signed, mysteriously, “Japonica.” Though she doubted that her professor wrote it, she allowed herself to half imagine the possibility. “I think Prof. Scott talks like he knows something about the Valentine,” she decoded, “but he could not have sent it.”

Clay, at sixteen, was entirely smitten. Her teacher, twenty-seven, had singled her out—that much she knew. The Annual Catalogue of Edgeworth Female Academy for 1856 says that William L. Scott, A.B., graduated from the University of North Carolina “with the highest honors of that Institution” and was “well known as an accomplished Classical and Mathematical Scholar.” He was in his first year at the school. How careful he and his student had to be in expressing their feelings for each other (though she was of marriageable age and he, at least on paper, a perfectly plausible match) is reflected in the coy glances that, for some time, had to suffice. Edgeworth’s Annual Catalogue for 1854 hints at the ambiguity, with “General Remarks” that read, in part: “Pupils are not watched, but sufficiently guarded for the detection of errors in conduct.”15

During her final semester at Edgeworth, Clay and her teacher were kept apart by one continually disapproving faculty member. At graduation, Clay received an “affectionate grasp of the hand” from her restrained beau, but nothing more demonstrative than that. Will Scott stood at the door of the school building as Clay’s carriage pulled away—their eyes remained fixed on each other, she tells her diary.

Finally, the young graduate arrived at her married sister’s place and met the imposing General Rivers. “I dont know exactly what to think of him,” Clay wrote with some foreboding. A package from Will Scott came in the mail: it was a leather-bound book called Knickerbocker Gallery. Tucked inside it was “a beautiful, tremulous little poem.” Clay’s expectations rose—she said she “dreamed over” the book. But it became apparent that her brother-in-law did not want her to marry a poor schoolteacher.

Will rode up in a carriage and met the family. He stayed an entire day. Clay was fixed on the delicate scent of jasmine and honeysuckle in the night air, as she wrote of the hours just past; otherwise she felt nought but her waning courage. “I was indeed loved by that noble, gifted man by my side,” she scratched out, “and yet—how could it be?” All day long, she had wanted to tell Will she loved him, but she dared not. “We sat and talked for hours. I know not what was said—I answered like one in a dream.”

Was it all a dream? After Will left, she was certain that her “abstracted” manner had left him wondering whether her feelings matched his. When she felt sad, she took out the lock of his “soft, silky, brown hair” that she had kept safe ever since a classmate had surreptitiously clipped it while Prof. Scott was helping someone else with an algebra problem. “He does not dream that I have a piece of his hair.” Days and weeks passed, and she received a hopeful letter from Will. “My dreams tonight must be sweet,” she wrote, “all soft and golden.”

Though she blamed herself for holding back, the uncertainty about her future was not of her making. The unimpeachable General Thomas Rivers opposed a marital alliance with W. Lafayette Scott. He may have persuaded his absent in-laws, too. As Will Scott was writing “dearest” and “darling” to Clay, their engagement, which had lasted nearly a year, came to an abrupt end. So did all her happy dreams. Rivers—“Bro’ Tom”—argued vociferously that Will did not really love her. “He does love me. I know he does,” she told herself. The battle between Clay and her brother-in-law escalated when Rivers commanded her to write a letter releasing Will Scott from any and all obligation. “There is no such thing as resisting him,” she wrote, unnerved. After “Bro’ Tom” read and approved it, she hid the letter in the “secret corner” of a private drawer and only pretended to mail it. Clay thought she had won. But Rivers was sneaky. He rummaged through her drawers, found the letter, and carried it to the post office himself.

On her eighteenth birthday, July 26, 1857, a consequential piece of mail arrived. Clay delayed opening Will’s letter, and her sister May and “Bro’ Tom” took charge, stealing it from her “unresisting hand,” reading it aloud. “I laughed wildly,” wrote Clay. “I was upon the verge of madness, my brain was in a whirl—my heart like marble. They read on. He had loved me fondly—but the dream was over.”

When she regained her composure, she returned his ring and all the love letters he had previously sent—standard procedure in any abortive romance. Tom Rivers insisted he would find her a wealthier, more suitable mate. Such words rang hollow. She went for long horseback rides, but neither this nor any other diversion worked. She simply could not forget Will Scott.

All she had left were her few tactile reminders of him. In addition to his calling card with her own “I’m dreaming!” on the reverse, she had his final expression of sadness and remorse: the note acknowledging receipt of the returned items. This note consisted of a single line: “Miss Clay:—Adieu, sweet lady, adieu!!! Will.”

“Ah why cannot I forget, since I know I am forgotten,” her diary reads. In September, darkness found her “committing to memory Young’s Night Thoughts,” the eighteenth-century epic verse we know for its constant drumbeat of mortal expectancy. Though in the light of day she practiced piano and guitar for hours at a stretch, she did not pick herself up and circulate in society.

Later, at her parents’ new house, in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, the dutiful daughter was surrounded by people who cared. Her mother perceived sadness beneath the gay exterior, half knowing the source of it: “She had reasons to think Genl Rivers was instrumental,” Clay writes. “I did not wish to tell her, even my Mother.” She did all she could to keep silent about the pain. “How could I hide my feelings from her who bore me—and such a dear, blessed Mother. She has but to look in my eyes, and she reads the workings of my heart.”

The other parent was even more protective of her:

Sometimes when I am sitting on the ottoman by the side of Pa, with his arm resting caressingly around my shoulder, as I always do at night, I feel I am not a woman grown, with a hidden heart sorrow, but only a child. The past seems to me as some beautiful dream. Every one treats me so much as a child, I cannot feel otherwise. Pa’s pet name for me is “Lap in Lay,” and he so often knuckles me under the chin and says “If any of the boys come after my baby, we will shoot them with a pop-gun, wont we ‘Lap in Lay.’” Then I hide my face in his bosom and tell him yes.

She had all but surrendered to a life of disappointment. Her plaint seems to be more than the gloominess after a breakup. The darkness inside had become so intoxicating that loneliness, resignation, and death whisper through the remainder of her diary:

January 1858: “Mortals are strangely constituted. They must have sorrow to make them feel the full value of happiness.”

February 1858: “Those words from [Byron’s] Childe Harold often come to me ‘There is a pleasure in the pathless wood,’ etc. Yes, ‘there is society where none intrudes.’”

March 1858: “Thoughts of one, loved and lost, whose name dwells ever in my heart, but passes not these lips. . . . He once said, ‘Tis better to have loved and lost than never to have loved atal.’ My hopes are blighted. Thus it is with life’s golden hopes.”

Her mother, bedridden for months, was by this time on the verge of death. To arrest the process of decay that the house reeked of, Clay attempted to restore to mind a better time, her “innocent and mirthful” childhood. “Memory will bring back the ‘olden time,’ with its wealth of smiles and hopes,” she writes. But even this sentiment redirected her to the loss of Will Scott’s love: “Yes there are times when Memory strikes cords too wildly mournful ever to be forgotten. In dreams comes back all the past—in dreams I see his face, and hear his voice Caress in a dream—’tis sweet to be bless’d. There is a void in my heart nothing else can fill. nothing.”

Habituated to seeing in dreams the still-promising face of the man she loved, she turned her disappointment into something less costly, less immediate. But then, on May 7, 1858, Thomas Rivers, Jr., sister May’s baby, barely a year old, breathed his last. “Little Tommy dead! Can it, Can it be?” This was the way of the nineteenth-century world. Christmas that year was quiet at the Dillard home, and Clay saw no better prospects. “I am in my room alone. No stockings hanging by the fire ‘in hopes that St. Nicholas will soon be there’—nor mysterious parcels such as have often excited my curiosity when a child. Bright dreams, and happy illusions come not again.”

All across the pages of her diary is the word “dream.” Representative of many privileged girls in the mid-nineteenth century, the uninhibited Clay Dillard was raised with the expectation that if she studied hard and obeyed those who watched over her, she would find a worthy mate. In some ways pampered, in other ways restricted in what she could aspire to, she pursued a life that was modeled on Maria Edgeworth’s upright women. The young were expected to dream now—that is, to consciously fantasize companionate love along with deep and devoted friendships.

It was in this manner that “dream” became a common noun and verb and exemplified the nineteenth century’s retranslation of the Declaration’s “pursuit of happiness.” In Jefferson’s day, “dream” most often described a “fallacious” or inconsequential thought, and the literal dream could be explained away as literally nonsense. The “pursuit” Jefferson had in mind in 1776 meant as much to society as to the individual. It meant working to build and defend a moral community. No dream of happiness could be realized except in the context of community. By the time Clay Dillard became socially aware, the pursuit of happiness more concretely embraced an individual’s path to the future. The way to happiness was available to any person who was ambitious for love and social position.

Individual dreams were expressed without being thought a “somnium”; dreams of personal happiness were no longer automatically part of a cautionary tale associated with unlikely aims or unrealizable ambition. In Clay’s diary, dreams refer to both her literal, nocturnal dreams and the larger dreams for life that she had been encouraged to cultivate. But all her hopes for a life in pursuit of happiness, a life that contained the love young women were now entitled to dream about, had dissolved into melancholy. All the education and all the literature—the power of awareness and discernment she was supposed to have acquired at the Edgeworth school—had not protected her. All that protected her was the infantilizing mirage created by a father who had formerly promised her a life as his “Lap in Lay.”

We do not know what happened to her over the next few years, because the diary contains no more entries by her. But we do know how Clay Dillard’s pursuit ended, and it was predictably tragic. In 1863, the one Clay called “Sis May” took over the diary and supplied a voice, because Clay’s had gone silent. May’s page was titled simply “A Dream,” and it told the dream Clay had related to her a short time before her final illness took hold. It turns out to be a reprocessing of the old, familiar vision of a journey to heaven and back, punctuated by music.

I had a deep dark abyss to cross on a narrow footway. After proceeding cautiously a few paces I was met by a sweet little cherub boy, who took me by the hand and conducted me safely over; when I stooped down and took him up in my arms to caress him, I found to my astonishment and delight “Little Tommy” whom I had loved so passionately, before he went with the angels. Soon a number of dear ones of other days met and welcomed me. I now heard strains of music and looking ahead saw a bright dazzling glorious City whence they proceeded. I listened as I approached and it proved to be Rock of Ages sung more exquisitely, more enrapturingly than any thing I had ever imagined or conceived. My friends said the inhabitants of the city spoke a strange language which I would not understand at first—I replied, you are mistaken, I have already learned it—and I awoke.

When her father died in 1859, Clay wrote that he had grieved over not seeing his little “Lap in Lay” in his last days: “Clay, God bless her, tell her to meet me in heaven.” Now that Clay was gone, the surviving sister characterized the tender heart she knew by invoking one of Washington Irving’s pathos-driven stories, one of the many that reminded their generation how hard it was for a broken heart to mend: “Like Irving’s dove in the Broken Heart,” May wrote of Clay, “she strove to hide from all the arrow that was preying on her vitals. I believe with that writer in broken hearts and that thus many lovely forms fade away into the tomb and none can tell the cause that blighted their loveliness.” She had not been the same since Will Scott was taken from her.

In reviewing Clay’s life of the mind, we see repeated the well-established literary symbols from which so many of the dreamers featured in these pages derived their inspiration: Edward Young’s Night Thoughts, Lord Byron’s Childe Harold, and Washington Irving’s “Broken Heart.” Interlocking themes of dream/death/memory persisted among those—especially educated women—who came of age in the nineteenth century.

Awake, we of the twenty-first century tell ourselves there is no reason to fear our dreams. We deny, disdain, and forestall the end of personhood with all the tools the modern world makes available. Actuarial evidence instructs us that we will experience only a very gradual physical decline. How much more “present” that feeling was in an age when the average individual died before fifty is difficult to qualify with any precision. But we know it was there.

That is what emotional history attempts to explain: qualitative differences between then and now. It is all meant to be presented in a detached, dispassionate manner. But when stories like that of Caroline Clay Dillard are placed before our eyes, and we imagine a time-bending communion, the emotionalism of those who came before is not so foreign seeming, so dead and buried. Their pathos reaches us. Still, we ask the question, first posed with cool objectivity: to what extent were they like us?

What we are able to grasp at this point in the narrative, with scarcely a doubt, is that their night thoughts contained strong passions, and their broken hearts were not just real, but like blinding sandstorms to them. They knew when they had agency in encountering life’s end, which was certainly not often. They knew (as we do) that the imagination is much more than a limpid pool inside the brain, waiting to be stirred and stimulated—it actively creates events, good and bad.

In 1863, the same year Clay Dillard took sick and died, Brigadier General Thomas Rivers also died of natural causes. This must be some kind of poetic justice. William Lafayette Scott enlisted in the 21st North Carolina infantry when war broke out and was elected captain of Company M, the “Guilford Dixie Boys.” He survived the war, only to die in 1872. To do the math, he outlasted by only nine years the heartbroken young woman who would have been delighted to marry him.16

Missourian Spencer Brown would serve as a spy for the Union Army during the Civil War and forfeit his life because of it. But in 1858, he was a sixteen-year-old cowhand on a farm, and his diary had nothing more dramatic to report than the weight of a catfish someone caught. But on a couple of occasions that spring and summer, he dreamt of love. He did not give his fantasy a name. It was just a feeling: “I had a dream last night—truly a dream. I dreamed that I loved and was loved again.” Gloom descended after he woke to a humdrum world. But at night, when he sat down to write, his mood changed: “I am cheered with hope.” A few months later, a similar good feeling arose in his sleeping mind: “I have worked very hard to-day,” he noted, and then explained why: “I had such a nice dream last night—I dreamed that I was loved. It made me work harder all day!” “Still,” the teenager added glumly, “I wake to a sad reality.”17

Francis Terry Leak was an attorney and plantation owner in North Carolina, born in 1803 and admitted to the bar at the age of twenty-one. In the late 1830s, he established himself in northern Mississippi. Much later, his diary would come to the attention of the author William Faulkner, who drew directly from it in some of his fiction.18

In the autumn of 1854, Leak wrote in his diary that he had dreamt of a Rockingham, North Carolina, friend, R. J. Steele. So he decided to write to him. Enclosing some “Java peas” from his plantation, he spelled it all out, telling Steele that “after looking at his daguerreotype a few evenings ago, I dreamed of him.” In the dream, Steele had come down for a visit, “and very soon after walking in the house, he enjoined me not to forget to show him, before he left, the branch [of a river] I had been speaking to him about, when in North Carolina, in reference to its capacity for milling purposes. I promised, of course, to attend to the matter, being much gratified at the opportunity of getting his opinion upon the subject.”

Here was a dream about forgetting and regretting, a familiar theme to any who have had the classic dream of arriving for a test unaware and unprepared. “Somehow or other,” Leak went on, “I did let him slip off without showing him the branch. I regretted this very much upon awaking, & still regretted it, because I then thought, & still think, that had I taken him over to the stream I should probably have obtained some of his ideas upon the subject.” So, in writing the letter to Steele, he made certain to ask for an opinion—precisely what he had neglected to ask in the dream. He explained, both to his correspondent and in his diary, “that I had often had ideas put into my mind in a dream which I could not account for by tracing them to any previous observations or reflections of my own.” He was convinced that one function of dreaming was to hatch original, constructive thoughts.19

Mrs. George Thurston was the wife of a Mississippi riverboat captain and mother of a small boy named Webster. She lived in the Deep South. Her New York–designed “Pocket Diary for 1858” is only unusual in that, for a period of several months, she jotted a brief, almost daily summary of her dreams. Only Ichabod Cook devoted more time in a single bound journal to regular notations of raw dream content.

June 28: “Dreamed was in the Catholic Church. Seen Some Girls dressed in white, knitting—awoke feeling bad.”

July 6: “Dreamed Riding on horseback and dancing.”

July 7: “Dreamed I seen [her deceased] Father. Seen some wonderful manifestation in Spiritualism.”

(Across the United States, the 1840s and 1850s saw a flowering of interest in Spiritualism, an offshoot of Christianity readily identified with séances, mesmeric trances, and especially the teachings of Emanuel Swedenborg [1688–1772]. Biographies of Swedenborg rolled from American presses. In the words of one, the Stockholm-born philosopher considered “the brain and nerves, or spirit vessels” as “channels of a transcendent or spirituous circulation.” Questioning traditional assumptions about heaven and hell, Swedenborg treated Judgment Day as a decision about the quality of a person’s spirit, unrelated to his or her adherence to sectarian principles. In Swedenborgian terms, all who yearned to communicate with the dead, all who thought that ways could be found to contact spirits, accepted dreams as a possible source of extraordinary knowledge.20)

Back to Mrs. Thurston:

July 10: “Dreamed of having something to do with chickens.”

July 11: “Slept Sound last night. Got up with the headach.”

(“Slept sound” meant that she did not dream. Periodicals of the 1850s upheld the dictum “perfect health insures dreamless sleep.” Personal dream records had heightened in complexity and deepened in self-discovery, but the public discourse had hardly budged: dreaming still indicated the existence of an internal problem—either a person had not been eating right or was suffering from an identifiable medical condition, as doctors since Benjamin Rush’s day had claimed. For Mrs. Thurston, though, sound sleep did not prevent a morning headache.)

July 14: “Dreamed Something about talking with B. about buying a woman” (a slave to do household chores).

July 15: “Had bad dreams about sick Babys. Webster is very sick, sent for the Dr.”

July 16: “Dreamed about putting out fire, killing a bird.”

July 17: “Dreamed about Dr. Davis thought he had grown so ugly.”

July 19: “Dreamed something about a letter.”

July 21: “Dreamed of having 4 different kinds of Birds in one Cage + caught another large one. Had some notion of giving lessons in painting.”

July 22: “Dreamed I seen . . . a strange Bird gave away half a hog then helped cut it up.”

July 25: “Had disagreeable Dreams, got feeling low, got the headach.”

July 26: “Dreamed I slept on my scissors & broke them.”

July 27: “Dreamed I had a difficulty with Mrs. Weed about a Servant & beat her.”

July 28: “Dreamed a man gave me a piece of a Tarantula.”

August 3: “Dreamed of being in a hotell.”

August 5: “Dreamed of having Some very large Strawberries.”

August 6: “Dreamed of climing up a [?] verry high to fly, then let all holds[?] go to see if I could not fly but I would come down again.”

Her husband, George, returned home on the morning of the sixth, after a long absence plying the Mississippi. He had been ill. We have none of George’s dreams to compare, but if Robert Stuart, another American seafarer at virtually the same moment, can serve as a stand-in, it is easy to imagine what the long absences must have produced in George’s mind. Wrote Stuart to his wife: “How strange it is that I so constantly dream of home, either yourself or one of the little darlings invariably appearing to me.” With her husband once again sharing her bed, Mrs. Thurston stopped recording her dreams and did not start up again for weeks:

September 1: “Dreamed I was in a strange place, a hotell. Seen deep water, rode horse back. had a dispute with Mr. Thurston a bout going Somewhere after Money.”

September 2: “Dreamed of having trouble Seperating with Mr. T. Thought after it was all over I felt comfortable.”

September 3: “Dreamed of seeing large trees that had been taken up and replanted close to a house.”

September 4: “Had disagreeable Dream.”

September 5: “Dreamed of spending most of our Money.”

September 6: “Dreamed I had a new bonnet, was trying it on.”

September 8: “Dreamed of broken Eggs and haveing to work hard.”

September 9: “Dreamed of being nearly to the end of the world and Seeing Some large Osien [ocean].”

September 10: “Dreamed I was in a Hotell. Seen Some dead men’s bodies covered up with a dead dog’s carcase. Went in the wash house and in the Soap house.”

September 11: “Dreamed I was making a pair of Pantaloons for a Tailor. Sewed them with a Shuttle. . . . Had on a dirty Dress. Seen some ugly men and women.”

September 12: “Dreamed of being in a boarding house. Stole a glove. Seen a floor painted with many colors, verry bright. Had Something to do with a Baby.”

September 13: “Dreamed of seeing Father. and I fear Some of us is going to be Sick.”21

There is considerable variation in Mrs. Thurston’s dream symbols—birds, babies, ugly faces, broken things, household tasks, money spent, strange

hotels—but what they all have in common is an emotional reaction to disorganization or the reorganization of her environment. Most of the dreams contain negative features, and none appears to suggest anything enduringly positive. Of the two wherein she saw the image of her deceased father, the first was hopeful, as it was accompanied by “some wonderful manifestation” of Spiritualism; the second struck her as a bad omen, predicting illness in her household. With her husband away for long stretches, adaptation to two distinct routines must have presented significant challenges, making stress unavoidable.

Mrs. Thurston’s pocket diary is informative in its listing of the incongruous household items that appear in her sleeping mind and the impulses they relate to. We can say with some assurance that these dreams, consisting of odd conjunctions (birds and hogs; broken eggs and hard work) and odd disjunctions (dead men covered up with a dog’s carcass), brought more dismay than conscious clarity. In a society absent of professional therapists, shamans, or an Ichabod Cook in the neighborhood to explain and soothe, there was no reliable cure for troubling dreams.

Mollie Dorsey was unusual. She accepted her visions, unorthodox though they were, and held her head high wherever she went. She persisted in expressing her mind, projecting her thoughts.

Mollie was not a witch, though people called her that. She began her journal in March 1857, at age eighteen, as she left Indianapolis with her large family and trekked west. When her father, William, brought them into Nebraska Territory, the area had been open to white settlement for only a few short years. They were real log-cabin pioneers. Mollie, with a venturesome spirit and a vibrant pen, wrote every few evenings by candlelight. She liked the prairie, and she always looked forward to sleeping and dreaming.

The land on which the Dorsey family settled was remote. Mollie described the view along the Nemaha River, “where myriads of tiny fish sport, and whose banks are overhung with creeping vines and flowers.” Aside from the occasional rattlesnake, which the other young people lived in fear of (and she, less timorously, kept an eye out for), her surroundings were pristine.

On June 29, 1857, she met blue-eyed Byron Sanford, who was twelve years her senior. “It is refreshing to meet a fellow like him after seeing so many flattering fops,” she wrote, all too aware that the rarity of marriageable women in the territory meant that word of her arrival was spreading quickly. In other respects, she seemed to adapt easily to this new life.22

That August, William Dorsey had just set out on a trip, and “a queer experience” occurred that Mollie felt compelled to relate. “I had gone to bed one night, but could not sleep,” she began. “My father was constantly on my mind.” She sensed that he was coming home, though he had been gone only two days and was not expected back for weeks. She rose from bed in the middle of the night and lit a fire to keep warm. Her mother awakened and came out to see what was wrong. “I told her I was looking for Father,” writes Mollie. “She thought I was losing my senses.”

But the impression in her mind continued to grow. “Hardly aware of what I was doing, I ground up and made some coffee. Mother was about to get up and shake me, when we heard the dogs bark, the voices, and soon Father was at the door.” He was accompanied by his traveling companions, Byron Sanford and a Mr. Holden. “Mr. Holden is a spiritualist,” she records next, “and readily accounted for it by saying I was a ‘medium.’” It was hard for her to believe, though she knew something extraordinary had just occurred. “I hope if I am controlled by any spirit,” she concluded, “it will be for good.” The day before, her brother was bitten by a rattlesnake. Unfortunately for young Sam Dorsey, Mollie didn’t see that coming.23

“Guess I’m going to be a ‘mejium’ or spiritualist whether I want to be or not,” she wrote in September 1857. The girl from Indiana did not know what the Great Plains, or as she put it, “this wild life,” held for her, but she was remarkably unafraid. She sensed there was something special about her, and that her powers of mind obliged her to look out for those she loved.

It was at this time that dream life first directed her actions. Her father had given her a pair of shell puff combs to wear in her hair. One day, she went off on a “long tramp hunting plums” with several other girls and boys and realized only when she returned home that one of the combs was gone. “It worried me half the night,” she wrote. “But I dreamed that I saw my comb on the limb of a certain plum tree I remembered, because it was close to an old deserted cabin a mile from the house.” After she had the dream a second time, she resolved to test its power. “I went to the tree, and there sure enough! just as I had seen it in my dream, hung my comb! My hair seemed to rise upon my head and my knees knocked together, but I had my treasure, and had also demonstrated the fact that there was something in my dream.”

Family members starting calling her “prophet” and “witch.” Not long after came the most amazing of all her night visions: “I saw in a dream a closed carriage drive to the door, containing a man and a woman, the woman wearing glasses, and a green veil, and the man driving one white and one bay horse. The advent of a female occurs so seldom that we never look for them any more.” Mollie proceeded to inform her family that they were going to have company at their log cabin home, come breakfast. She described the woman. Only one of the Dorsey clan believed in what Mollie now called her “prognostical spasms,” and she was filled with anticipation, “perched by the window to watch the road.” Soon enough, “an excited exclamation brought us to see the identical carriage, the white and bay horse, the man, and stranger yet, the woman with the glasses and the green veil.” It was a couple who had come to visit relatives in the area.

Mollie finished telling her tale. At nightfall, the travelers had stopped six miles away at a “bachelor’s cabin,” where the woman in the green veil was assailed by bedbugs and then refused to stay for breakfast with the unclean bachelor. So the party started out early and arrived at the Dorseys in time for breakfast. When told of Mollie’s dream, the woman in green said: “There’s no use talking—you are a medium.” Mollie accepted who and what she was, writing: “I cannot explain, nor do I try to.”24

The next spring, she moved to Nebraska City and took up work as a dressmaker. In the intervening months, given her eligibility, she had several suitors. She told herself she would not make a choice of husband until she turned twenty-one. There are no dream entries for the year 1858, though Mollie did continue to ruminate on her natural abilities: “I have many seasons of sublime and poetic thoughts, and often soar above the cares of life into a world of my own, into whose portals no one may invade. It is well perhaps that I have to battle with stern realities. I might become an idle dreamer, for I have not talent enough to make much of myself. I used to dream of being an author. . . .” She is slightly older, and sounds it. She has also resolved that “By,” as she called her new beau, Byron Sanford, was “a good match for me. He is so thoroughly matter-of-fact and practical that it will help equalize my romance and sentiment.” She declared to her diary that she loved him.25

At nineteen, with thoughts of marriage entering her mind, Mollie apparently considered her prophetic visions to belong to the past. She was no longer a “mejium,” no longer living through dreams. Except that on the last day of February 1859, while staying with a family an hour outside Nebraska City, she was again startled by a vision, and a deeply disturbing one. It came to her not long after she had learned that her cousin Mary, in Nebraska City, was unhappy with her new stepmother. Mary’s widowed father had married “suddenly,” and it seemed to unleash a season of ill fortune.

“I feel sad and depressed today from the effects of one of my dreams last night,” Mollie recorded. “All night long when I slept I could see Cousin Mary first a bride and then in a coffin, and waking, I seemed to hear her calling me. Mother says I am morbid and must have a change, but no! There’s something wrong and I fully expect before night to hear bad news.”

There was a hill where one always caught a first glimpse of teams of horses approaching the little town, and Mollie found herself looking anxiously in the direction of that hill. “I wish I were not this way,” she wrote, “and maybe after all I am morbid or something else. I do not dwell on imaginary or impending evils, and these impressions come unsolicited.”26

But just as she predicted, that very night her Uncle Frank rode up on horseback and delivered the news: “The moment I saw him my heart beat faster. I said, ‘Uncle, you bring bad tidings?’ He looked surprised and said, ‘Who told you?’ I said, ‘What is it?’ He said, ‘Your Cousin Mary has had a hemorrhage and cannot live, and is constantly calling you.’” There is nothing in the analytical character of her writing, at this or any other time, to suggest Mollie was lying or allowing an admittedly rich imagination to get the better of her. In fact, except for those occasional reflections on her gift of prophecy, her writing is marked by utter earnestness.

She returned to Nebraska City and cared for her cousin. This meant, too, that she had to tangle with the evil stepmother, who seemed to her strangely jealous of the dying girl: “She has a natural antipathy to Mary,” Mollie wrote.

The pathos of the deathbed scene, a staple of early American literature, was replicated in Mollie’s diary. “O! Mollie,” Mary cried out to her. “I shall be soon where flowers never die.” It was on May 4, 1859, after Mollie had begun a new job as a schoolteacher, that she recorded her personal loss: “I come with saddened heart and tearful eyes today, my Journal. This afternoon Mary was laid away. She called for me the eve before she passed away. Through the stepmother’s misrepresentations I did not get the message, and only heard of the event in time to reach the house for the funeral services.”27

She and By were married on St. Valentine’s Day, 1860. When the snows melted, the newlyweds moved farther west, to the rugged metropolis of Denver. Mollie’s portentous dreams stopped, or at least she stopped recording them in her journal. Other things were happening that took precedent. She delivered a baby who did not survive, and she and her husband got to know the Colorado governor and played cards with the Indian agent Albert Gallatin Boone, grandson of the trailblazing Daniel Boone. The Sanfords were upstanding citizens of the territory.

With the outbreak of war, Byron Sanford enlisted in the Union Army, assumed the rank of lieutenant, and in the spring of 1862 saw action at the Battle of Pigeon Ranch, New Mexico. Mollie waited nervously for word of the fighting and word from her husband. And then there was this journal entry: “Last night while brooding over my troubles I had one of my impressions that By was coming home . . . and sure enough! this morning the advance guard arrived, and as Col. Slough shook hands with me he said, ‘Let me congratulate you, Madam. You will soon see your husband.’ And so my dream came true.”28

The decade of the 1850s produced an astounding number of dream vignettes—those recoverable from personal diaries and those featured in the public papers. Children’s literature of this decade featured dream-based tales, often the sort in which an angel led the sleeper through “liquid realms” of heavenly firmament. The didactic Sunday School-Teacher’s Dream took its author to the world beyond, allowing him to watch a drama play out between a former colleague and the delinquent student he had failed to inspire—both, as a consequence, were troubled souls. On waking, the afflicted teacher resolved: “I have never met my class since that memorable night, without a vivid recollection of every circumstance of my dream.”29

Many deeply religious people would store up a dream so powerful that it became part of a devotional. Priscilla Munnikhuysen held fast to one in particular, which she felt protected her soul from degradation. The twenty-year-old daughter of a Dutch immigrant merchant, she lived outside Baltimore in the late 1850s and attended the Methodist Church, where she enjoyed a good sermon. “I once had a dream which has left a lasting impression on my mind,” she wrote in her diary. “I dreamed I was walking along a road leading from our house to one of the neighbors’, and I came to a run where I had to cross before I could reach the house I was going to, and when I looked I found there were no stepping stones or any other way of crossing that I could see.” The obstacle was great, but so was her faith. “On looking up very far I saw a log, as it were fastened up by bushes, and seeming to be almost entirely suspended in the air. But I thought I had to go, and although the way looked dangerous, I had to cross over. On looking up I beheld our Savior looking down at me with a halo around his head, more like the sun, and as I looked up He said, ‘have faith in God.’” It had been some years since she had had this dream, and yet, “it is as fresh in the halls of memory as when I dreamed it.”30

Then there was Martini Brandigee of Detroit, who spent the night at the home of a family friend and came to breakfast with a dream to report: “Oh, Mrs. S., I have a sweet Heavenly vision—I could not sleep for excitement.” She had found herself in the girlhood home of a friend they shared, who was now deceased. Their friend was not shrouded in mist, but appeared as her earthly self—yet “surrounded by a halo of light.” She whispered to the dreamer, “Martini, is it you?” Martini could not speak, which the deceased seemed to understand, and proceeded to sing a tune for her that they had formerly sung together.31

Mysteries of science were as popular as mysteries of faith. In 1859, Harper’s Weekly published “A Physician’s Dreams.” The author, English, had observed a patient whose brain was exposed as a result of an accident. Adopting a metaphor of modern communications, the doctor laid out what the naked brain had revealed to him: “In a waking state, the brain had intelligent . . . telegraphic motions, correspondent to the thoughts which it was printing off. . . . But in a state of sleep the patient’s brain worked and telegraphed no more. It became a mere pulse, like that at the wrist.” From this, he concluded, sleep was “quietude,” and someone unable to get a night’s rest could not but “drown the busy brain in a kind of artificial apoplexy.”

Good men have bad dreams. One was not to judge character on the basis of dream content. The doctor could only conclude, as his eighteenth-century predecessors had done, that external (physical) or internal (physiological) disruptions made dreams what they were. With epigrammatic force, he proclaimed: “Indigestion, both in its labor and its fatigue, is a prolific hag-mother of ugly dreams.”

He tried not to address his reader in absolutes. “I imagine that a dream of sound is caused by an actual sound . . . , perhaps nothing more musical than a London cry.” (Perhaps this is what he would have told Dr. Rush about his Final Judgment trumpet.) The sleeping mind was too “idle” to create elaborate theater by itself, and so if “some stray memory, some throb in the blood, makes us wish to hear a singer,” a fractured effort on the part of the brain, a “momentary volition,” might produce a facsimile of it, but a weak facsimile. And this, in a phrase, explained the bizarre imagery that dreamers experienced.

Undertaking a self-examination, the doctor found that a little too much wine with dinner could bring on a nightmare. “I imagined myself to be in some unknown country, arriving at a mysterious hotel. I was put to sleep in a mysterious room, which resembled the hall of an old castle. . . . I was lying in a dim, shadowy bed.” Standing imposingly in all four corners of the room were statues of men in armor, which before long came alive and began to move toward him. “The sense of the supernatural now became in me horrifying and intense. . . . I struggled to get up, but could only utter faint cries.” All at once, as the men in armor neared his bed, “a sudden change came over me. I felt loosed from my nightmare bonds, and by a prodigious effort leaped out of bed.”

Once awake, he gradually realized that there was no flesh-and-blood thief in the house, only a terrible dream in his head. With this reassurance, he returned to bed and fell asleep easily. The dream renewed, but instead of a nightmarish attack, it morphed into “a pleasant tour.” He was still traveling to unknown places, but the haunted inn was left behind, and a lighthearted feeling replaced fear. Having battled past the effects of wine midway through the night, he was able to pass several good hours: “I awoke with a feeling of mingled amusement and comfort.”

In the 1840s and 1850s, dream books and itinerant seers tapped into common anxieties more than ever before. Dream books held the key to instant salvation, promised an end to chaos, and offered a means of reversing the hopeless spiral into which the financially strapped were sinking. While better-educated people arranged séances or turned to Transcendentalism or Swedenborgian mysticism, more ordinary folks found themselves led into the “vernacular divination” provided by dream books, where supernatural messages were hidden in dream symbols. There was no clear winner in the competition between popular science and popular religion.32

This was also the era of Joseph Smith, the martyred visionary, and his successor, Brigham Young, who journeyed west to establish the Mormon Church in Utah. In Mormonism, dreams and visions carry great weight. Many are archetypal, involving a glimpse of heaven and loved ones who await the dreamer there. But while going west with Brigham Young in 1847, thirty-three-year-old pioneer William Clayton recorded a dream about his Mormon fellows that contains those raw elements, free of religious sentiment, that speak to the cultural project we are addressing.

Clayton dreamt that the traveling party had stopped beside a deep river. “Our horses and cattle were tied to stakes all around the camp to the distance of a quarter of a mile, some good timber thinly scattered around.” He thought he spotted Brigham Young and others moving away from them, heading up the river in a flatboat. “When they had been gone some time I thought a large herd of buffalo came on full gallop right amongst our horses and cattle, causing them to break their ropes and fly in every direction. The brethren seemed thunderstruck and did not know what to do.” This was when the dreamer found himself taking charge and arresting the panic: “Seeing a small skiff in the river, I sprang into it, and a paddle lying in it, I commenced rowing in pursuit of the President [Young]. It seemed as though I literally flew through the water.” He succeeded in overtaking the leadership, and as he brought the skiff to shore, he suddenly realized that it was full of cracks and incapable of having gone upriver without sinking. “The paddle,” moreover, “proved to be a very large feather.” In the end, the party he had chased after thought nothing of the incident back in camp; they “seemed no ways alarmed.” It was at this moment in his dream, with the impossible coming close to believable, that William Clayton awoke.33

One can only assume that as American families migrated west, crossing rivers and fording streams, many people experienced this same species of dream. Physical exertions in one’s daily life could translate easily into physical challenges within the dreaming mind.

“Dreams,” says a writer, “are the novels which we read when asleep.” This is one of the gems in an anthology of wisdom and verse relating to dreamscapes. The Poetry and Mystery of Dreams, published in 1856, declared itself to be a poetic refrain, not a prophetic guide. Dreams were no longer “sources of hope or fear,” according to the book’s compiler, “but they are still recorded as mysterious or pleasing fantasies, still narrated at the breakfast table, and still quoted by lovers as affording involuntary illustrations of a passion which dares not declare itself in more direct terms.”34

When literal dreams were voiced unreservedly at the breakfast table, something meaningful was going on. Mollie Dorsey was never thought afflicted, though her mind wandered into the occult. Where book reading was a rich pleasure within families, vivid, psychologically drawn characters translated into ever more demonstrative diaries. It was reaching the point where the animated individual exuded an energy that had physico-chemical properties. “Of physiology from tip to toe I sing,” penned Walt Whitman, who published Leaves of Grass in 1855 and assimilated the song of nation into the song of self. “Of Life immense in passion, pulse, and power,” he hummed, “Cheerful, for freest action form’d under the laws divine, The Modern Man I sing.”35

Science is now saying that we are wired in favor of optimism, no matter how much we police morality or dwell on our mortality. Recent studies show that narrative consciousness collects and distributes our visual stories in convenient ways in order to feed a built-in sense of our resilience. Humans are adaptive, meaning we take our traumas, our living nightmares, and try to construct scenarios around them so that they do not impede progress toward the future.36

That optimistic undercurrent may be what we are seeing as the nineteenth century moved along. Yes, nineteenth-century lives were strewn with death. In and out of dreams, they knew a more profound helplessness than we do. Among the individuals whose stories have been collected in these pages, morning consciousness seems most positive when dreams removed the dreamer to a childhood scene or to a place far away. Nostalgic or utopian visions were the easiest for them to express.

None of this meant that conformity had come to an end in America. We see, despite the increased appearance of odd objects and unique configurations, that dreams such as Clay Dillard’s were populated with angels and dead loved ones. What the record does show, at least, is that the middle decades of the nineteenth century witnessed an upsurge in dramatic encounters within dreams, without stuffy rationalizations.

For the heartbreak kids, if we might dub them that, dreams produced just enough of hope to offset the omnipresent prospect of devastating loss. In Madaline Edwards’s case, dreams of love were brief interruptions in a life of emotional betrayal. Clay Dillard, her father’s “Lap in Lay,” was never allowed to grow up. Her dreams symbolized what she was deprived of in reality and could not acknowledge to her family; they were her passage to freedom and independence, to an alternative life where she could live out the desire to know and enjoy love. In contrast to Madaline and Clay, the self-assured Mollie Dorsey dreamt and prophesied as a means of coping with ambiguity, thereby obtaining mastery over her emotions.

Their stories detract from the typical narrative requirement of charting progress over time. Aside from Mollie, whose “sixth sense” made her as much a seer as a dreamer, the other individuals we met in this chapter whose lives can be reconstructed with emotional complexity were fated to lose love and die before they had a real chance to make a mark on society. One would only expect that the Civil War, America’s first modern war, stood to intensify the tragic dimension in dream telling. But that is only partly true.

Edgeworth Female Seminary (Greensboro, North Carolina) in the mid-1850s, which Clay and May Dillard attended, and where William Lafayette Scott taught.

“O! I’m dreaming.” Reverse of Will Scott’s calling card. The secret words (in Clay Dillard’s hand) are hidden on the back of the card, which she pasted into her diary. Much as she loved Will, her overbearing brother-in-law prevented them from marrying. Courtesy of the Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill.