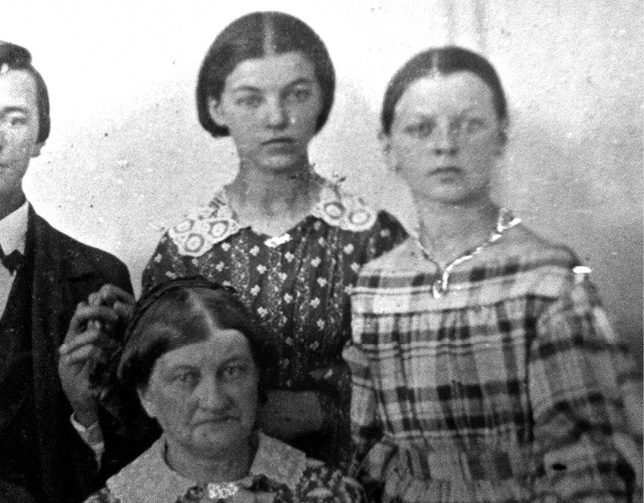

Adelaide Case and family. Addie is on the far right. Courtesy of the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

Lincoln Dreams He’s Died

Dreamed of home last night. O Dreams! Visions! Shadows of the brain! What are you? My whole consciousness, since I heard of President Lincoln’s assassination, seems nothing but a horrid dream.

—Alexander H. Stephens, vice president of the Confederate States of America, June 1865. He penned these words from prison, three weeks after his arrest.

John C. Calhoun was twice an unhappy vice president, and for years afterward a magisterial, if, to many, a chilly presence in the U.S. Senate. In the 1820s, the Yale-educated South Carolinian defected from John Quincy Adams’s administration to support Andrew Jackson, only to fall out of favor with Jackson. As a senator, he gave early voice to a theory of disunion, and his sturdy defense of slavery added to his luster in the South as war loomed.

A couple of months before he died, Calhoun had a “singular dream,” if one is to accept the inventive George Lippard. In January 1850, the story went, the senator sat down to breakfast with Congressman Robert Toombs of Georgia and exhibited tremendous agitation. Toombs noticed that Calhoun was looking down at his right hand. He asked whether the senator was in any pain. “It is nothing!” Calhoun exclaimed. “Only a dream I had last night.”

In the hours since dawn, he had continued to see a black spot (“like an ink blotch”) on the back of his hand. George Washington had come to him, dressed in Revolutionary garb, and pressed him about his intention of signing a “Declaration of Disunion.” It was as Washington was speaking that the black first appeared on Calhoun’s hand. Said Washington gravely: “That is the mark by which Benedict Arnold is known in the next world.”1

In March of that year, as Calhoun lay dying in Washington, D.C., word began to get around. The Wisconsin Democrat prefaced “Calhoun’s Dream—The Union” with an editorial tease: “The Washington correspondent of Lippard’s paper the Quaker City, communicates the following curious account of a recent remarkable dream of Mr. Calhoun’s. The allegory is certainly well carried out.”

Even when presented as an allegory, however, some were persuaded that Calhoun did actually have some sort of prophetic dream. The senator’s daughter-in-law, Margaret Green Calhoun, was credulous enough to write from Alabama’s cotton-rich Black Belt to her sister, then in Washington, asking about its authenticity. “The dream you speak of in your letter I had never heard of,” replied Eliza Green Reid. “I have inquired however & learn that most persons think he never had such a dream as the one in the papers[;] he had a dream but I cannot get the correct account of it. I have heard several, all different, as soon as he is well enough I will see him and get his own version of it.” But of course, Senator Calhoun never recovered, so whatever dream he did have eludes the historian.2

Before inventing Calhoun’s dream, George Lippard had earned renown as the author of a nightmarish book about urban vice and violence. Though a devoted fan of Edgar Allan Poe, Lippard chose to dedicate his novel The Quaker City (the same title he later gave to his weekly) to their long-dead predecessor in the gothic arts, Charles Brockden Brown. Lippard’s sadistic character Abijah K. Jones, better known as “Devil-Bug,” is so warped that he longs to live among the phantoms of those he has murdered. As his story unfolds, Abijah has a dream in which his victims rise before him. Blood drips and confusion reigns amid groans and whispers and grotesque laughter. Coffins float by the dreamer’s inward eyes. The sun assumes the shape of “a grinning skeleton-head,” dancing stars gleam “through the orbless socket of a skull” (recall the dream in Richard III), and a blood-red crescent moon rises. The haunted heavens disappear at once into a “thick and impenetrable darkness,” and Devil-Bug is treated to the shrieking sounds of “the Orchestra of Hell.”

Lippard wrote the sequence of sudden movements in a way that reproduces the emotional battlefield of a literal dream, capturing the cool, cruel concoction of a nightmare. But if Devil-Bug got what was coming to him, so did Lippard: the prolific young author turned out to be another heartbreak kid, dying of tuberculosis at thirty-one, in 1854. His work and his abbreviated life serve to remind us again that even before the photographed bloodshed of the Civil War, Americans were witness to disturbing images and inescapable personal tragedy.3

Whether or not the dying John C. Calhoun had a dream worth telling, he no longer believed in 1850 that North and South could coexist as one nation. In words he dictated to his private secretary, a New York City journalist, he said ominously that “the time had come” for the two sections to settle the slavery question “fully & forever.” Planting seeds of discontent, the South Carolinian made many of his peers nervous. “Mr. Calhoun’s death has deified his opinions,” one northern judge noted, “and he is therefore more dangerous dead than living.” And perhaps he was. South Carolina, the first state to secede, went its own way in December 1860; within three months, the rest of the Deep South had joined in rebellion, awaiting only Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee to make the Confederacy complete.4

Only the South’s final defection enabled the northern states to find common cause. In 1860, even the dreamy Transcendentalists of the 1840s were disoriented and divided. Nathaniel Hawthorne returned from seven years abroad as a diplomat to find his old comrades Emerson, Thoreau, and Alcott viewing the coming war as the culmination of a moral crusade to open minds and save souls. Hawthorne bristled.

An event of October 1859 had put the final nail in the coffin. John Brown’s bloody, badly organized raid on the national armory in Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, had been designed to spark a race war. In its wake, an unrestrained Emerson called the violent abolitionist a “saint”; Thoreau uttered a plea on behalf of the convicted terrorist on the eve of his hanging (and martyrdom). Months later, Concord’s schoolmaster brought two of John Brown’s children to the town; they stayed with the Emersons and went to school with Hawthorne’s son Julian.

When war broke out, Concord sent a company of volunteers to the Army of the Potomac. Gloomy Nathaniel Hawthorne did not join in the celebration. The bestselling author of The Scarlet Letter, a story of dark secrets, took solace in the fact that Julian, though old enough to have his eye on Harvard, was too young for soldiering.5

On the other side of the Mason-Dixon Line, a dreamer with dark secrets wrote in her diary on the day after Fort Sumter surrendered to the Confederacy: “O Lord let the N. & S. compromise & shed no more blood. . . . I never believed I should live to see my Country severed.” She was Keziah Hopkins Brevard, a fifty-seven-year-old widow living alone with her numerous slaves on a six-thousand-acre plantation outside Columbia, South Carolina. Her late husband had been a state legislator during the first year of their marriage, but he was also a heavy drinker. He became so obsessed with his wife’s fidelity that he went around monomaniacally hunting for her paramour, until he was finally hospitalized and then, after a few short weeks, pronounced cured.

Keziah, or “Kizzie,” as she was known, recorded a series of dreams in the second half of 1860. The coming of war deeply affected her, and its disruptive prospect fed her dreams. July 31, 1860: “Last night I dreamed there was to be a commotion of some kind in Columbia. . . . I do hope there will be nothing to correspond with this dream—I don’t wish to be superstitious.” Five days later, she dreamt that James Hopkins Adams, the only son of her half sister, had returned home. He was a Yale graduate and a recent governor of South Carolina, and he would shortly sign the articles of secession. “I thought I was up a stair—I know not where,” Kizzie wrote. “I saw J.H. comeing up slowly & looking wearied with a complexion of death—I thought I clasped his hands in mine & exclaimed My God! My God! I thought he said to his wife ‘Oh you don’t know how you cheer me.’” Adams, father of eleven, died the next year.6

The final day of December 1860 yielded to a particularly dreary night of rain and wind, and Kizzie was roused from sleep several times. “I woke dreaming an alarming dream—thought singular clouds were flitting over my head while I stood near an old brick oven of my mother’s—while these clouds were fearful over my head—I saw in the S.E. corner of the yard two raging, smoking fires, the flames bursting high at intervals.” (Recall the conflagration dreams of Washington Irving and Ichabod Cook, the latter of whom also denoted the direction of the fire.) Under threat, Kizzie imagined that she was urgently calling to her slaves and ordering the fires to be extinguished. “Lord save me from trouble,” she wrote next. But it wasn’t war she was concerned about: “This is the last day of 1860—am I nearer my God than I was one year ago?”

As the political times worsened, the widow Brevard continued to note down her troubled dreams. On April 2, days from the fall of Fort Sumter, she dreamt she was in the Presbyterian church in Columbia, sitting “either in or near” the pew of another planter’s wife. “I thought Old Mrs. Bell sat at my right & young ladies at my left—I soon missed Mrs. Bell—I turned to my left & saw Mrs. B. M. Palmer [the former pastor’s wife] going from the pulpit up the aisle to the door—she was dressed in deep black with a bonnet trimmed very much. Some one told me she had been up to the pulpit taking some bandages from Mr. P’s face—his health was feeble & he had to use them.” The odd thing about this picture is that Benjamin M. Palmer had not been the pastor at her church for five years, having relocated to New Orleans.

“I thought Mr. P looked sunken near the eyes,” Kizzie continued. “Then immediately I found myself alone—looking around, every one had left the church & gone out doors to hear the preaching.” So she followed and on the way out spotted an “old neighbour” of her mother’s, long since dead. The neighbor was “sitting on a chair looking very cheerful & happy.” So she proposed accompanying her, and the woman said: “Not while Mr. P was there.” And that was as much as the dreamer remembered. Nothing made sense to her. “Is there any thing in dreams?” she posed. Later in the day, one of the slaves ran up to her and told her that one of her fields was ablaze.

Keziah Brevard repeated the cheerless refrain of so many: that she lived in a world of uncertainty. The day after her church dream, she said she was willing to give up her wealth if only North and South would reconcile. Referring to her home state of South Carolina, she wrote bleakly: “I do not love her disposition to cavil at every move—My heart has never been in the breaking up of the Union.”7

Freud’s theory that dreams often involve unacceptable desires and preoccupations seems entirely apropos at this turning point in history. As the abolitionist press was calling for across-the-board emancipation of the slaves, future secessionists printed anti-miscegenation engravings, hard-nosed editorials, and fanciful novels celebrating—we might call it daydreaming—the happy extended southern family. From The Partisan Leader (1836) to Wild Southern Scenes (1859), dreamy novels of southern independence, obtained bloodlessly, painted the North as overbearing and dictatorial. When the South finally went its own way, taking its chivalric dreams to the battlefield, it was persisting in a long-cultivated style of wishful thinking, hoping it would never have to wake up.8

In the North, too, the general feeling was that the Civil War would not last half as long as it did. But not everyone held this view. Calling the war “unsurpassed in the history of Christendom,” Henry Boynton Smith of Maine predicted a long and bloody conflict: “I apprehend that few yet realize the sacrifice it may, must cost.” Smith was the founder of a short-lived magazine, The American Theological Review, which published its first number in 1859 and its last in 1863. He proclaimed his periodical to be nondenominational, with theological, not ecclesiastical, objectives. “God’s good providence,” he said, would decide whether slavery outlived the war. Smith had become acquainted with New England Transcendentalists in the 1840s: “A strange set they are, full of what they call inspiration . . . but their belief yet shrouded in dreams and phantasmagorical shapes.” He heard Emerson lecture and adjudged his theories “partial truth and total error.” Beyond Henry Boynton Smith’s religiosity, he was a fervent patriot who attended the inauguration of Abraham Lincoln in Washington.9

Tayler Lewis was for several decades a professor of Greek at Union College in Schenectady, New York; and he was the author of The Divine Human in the Scriptures. In January 1862, he offered up a deeply humanistic meditation on the soul’s affections for the American Theological Review, building on the themes of his book. He told of an old gypsy, an unschooled centenarian, who asked an English-speaking friend whether he had ever thought that the “outer world”—what we take for reality—existed only in our minds, “and that each man, in fact, made his own world.” His solipsistic dream had haunted the gypsy throughout his life. Buddhist doctrine held that “All is a Phantom,” noted Lewis. Maybe, just maybe, our musing was as real as the rest of existence.

After weighing the gypsy’s notion, Lewis pondered whether “the senses that God has given us” could deceive. Humans appeared to him to dream in a “hard material world,” doing so purposefully. Yet the professor would not dismiss the possibility that an intense reality without materiality was also possible. A nonmaterial sensory reality.

He was defining dream as feeling. External and internal forces operated upon every person differently—“such has ever been the language of the musing mind.” The science of invisible effects was still very young, and Professor Lewis would only say that he believed there was common ground between science and faith, between their two perspectives on the nature of the mind.

Narrowing his focus, Lewis addressed what dreamers since Dr. Rush had known as a register of inner life: the faculty of hearing. “The rational soul alone perceives music,” he philosophized. “The sense only feels, and what it feels is only noise, a roaring in the ears, until the intelligence sees (we were going to say hears) its own ideas, its own harmonies.” The rational soul, that which separated men from animals, had a nice ring to it. Music helped one understand spirit. The strings and vibrations of what Lewis called “musical science” needed no external confirmation to register the emotion of joy, any more than an inward vision needed external confirmation to create a comparable effect. Spiritual perception arose from some nonmaterial place, and that was that.10

In 1860, putting his own twist on the mystery of dream life, the opiated French poet Charles Baudelaire published Les paradis artificiels, in which he wrote:

Man’s dreams are of two classes. The first kind, filled with the details of his ordinary life, his preoccupations, his desires, and his vices, combine more or less bizarrely with objects seen in the daytime. . . . But as for the other kind of dream! the absurd, unexpected dream, unrelated and unconnected to the sleeper’s character, life, and passions! This dream . . . represents the supernatural side of man, and it is precisely because it is absurd that the Ancients thought it divine.

Abraham Lincoln, who steered America through its national nightmare, was a very active, suggestible—even superstitious—dreamer. As president, he repeated his dreams to those close to him: an entire chapter in the memoir of Ward Hill Lamon, Lincoln’s personal bodyguard and confidant during the war, is devoted to “Dreams and Presentiments.” Born in Virginia, Lamon arrived in Illinois at the age of nineteen, in 1847, and passed the bar four years later. He was six feet two inches tall, nearly as tall as Lincoln. As a trusted friend of the president-elect, he accompanied Lincoln by train from Springfield to Washington, organized and commanded a regiment of volunteer infantry in 1861, and for the balance of the war served as marshal of the District of Columbia as well as Lincoln’s personal assistant in several capacities—most particularly in guarding the president from physical danger.

Colonel Lamon explains in his memoir that Lincoln, an avid, gifted storyteller, found various ways to communicate a sense of foreboding. For example, he told Lamon of the night he broke free from imprisonment in the White House and went for a ride, alone, on “Old Abe,” a favorite horse. “Immersed in deep thought,” the president was shocked into a hypervigilant state by a rifle shot, courtesy of a “disloyal bushwhacker” who stood not fifty yards from him. In Lamon’s retelling, the president narrowly escaped a sniper’s bullet, lost his hat in the confusion, and chose to convey the nearly deadly story in a light, informal way. That was how Lincoln operated. Years before, he had informed his law partner, Billy Herndon, that he expected his life to come to an unfortunate end. But even these words were not spoken with sullenness or the least irritability. Lincoln lacked the capacity for self-pity. He was simply a superstitious man who tested the fate he prophesied for himself.11

In an antiwar speech Lincoln gave before Congress during the Mexican-American War in 1848, he compared one of President Polk’s bellicose messages to “the half-insane mumbling of a fever dream.” Obviously, scoffing at one species of dream did not mean the future president was a scoffer of dreams in general. In the 1850s, friends sometimes saw him enter a trancelike state, unmistakably lost in reverie. And before that, as a young lawyer in the 1830s, he had a distinct fondness for the faraway poetry of Lord Byron. One of his favorites was the one that opened: “I had a dream that was not all a dream.” Lamon often heard the president repeat lines from that poem of Byron’s titled “The Dream”:

Sleep hath its own world

A boundary between the things misnamed

Death and existence. Sleep hath its own world

And a wide realm of wild reality.

As Lincoln scholar Douglas L. Wilson points out, Byron’s poem “underscores the importance of the submerged half of one’s being.” Indeed, Lincoln’s brooding side was no less a hallmark of his personality than his famous wit.12

He spent his younger years in Kentucky and Indiana, among plain people who, Lamon writes, “believed in the marvellous as revealed in presentiments and dreams.” Lincoln imbibed these notions. He could be encouraged or he could be undone by his dreams, convinced that there was much to be made of them. At the time of his renomination in 1864, he flashed back to “an ominous incident of mysterious character” that had taken place in the fall of 1860, upon his election as president. It was, Lamon says, “the double-image of himself in the looking-glass, which he saw while lying on a lounge in his own chamber in Springfield.” One image was full of life, the other reflecting a “ghostly paleness.” Lincoln could not exorcise the vision from his mind, and the meaning of it was plenty clear to him: “safe passage” through his first term, death before his second was completed. Of Lincoln’s concern with this presentiment, Lamon was insistent. He blasted Lincoln for his carelessness in exposing himself to unnecessary dangers. It seemed that the president could not hide from (nor would he take action to evade) the torments his mind was prone to.13

In 1861, as the sixteenth president was just getting accustomed to being the occupant of the White House, First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln received a curious letter from a woman in Rochester, New York. It began with an apology to “Mrs. President Lincoln” for the intrusion on her time. Then, lest her foreign surname cause confusion, the writer attested to her parents’ homely origins in Vermont and her own previous work at a New York City weekly newspaper, where she met her “sober honest industrious” German-born husband, who shared her admiration for the new chief executive. Then, Helen Rauschnabel got to her true purpose in writing, which was to relate “a remarkable dream I had last night about Mr. Lincoln which I think has a significant meaning.”

I dreamed it stormed & thunderd & lightned terribly, it seemed as tho the Heavens & Earth were coming together, but it soon ceased, still there seemed to be very dark clouds sailing thro the horison, I thought I stood pensively viewing the scene, when a man resembling Mr Lincoln appeard standing erect in the firmament with a book in his hand, he stood as near as I could calculate over the City of Washington, his head seemed reard above the lightnings flash and thunder bolt, the sun seemed to be just rising in the East. . . . I saw him walk thro all the Southern part of the horison with a book in one hand, & a pen in the other.

As the Lincoln of her dream turned west, he was “crowned with honors & coverd Laurels, and looked very smiling.” The dream ended, but not before Mrs. Rauschnabel thought she clapped her hands and sang a song that contained the lyric “Slavery is ended & Freedom is born.”14

The war began in earnest, and General George McClellan was put in charge of the Army of the Potomac. A broadside appeared in late 1861 or early 1862, titled “General M’Clellan’s Dream,” meant to describe “something supernatural almost” in the commander’s troop movements. As a dream narrative, it bore striking similarities to the invented dream of John C. Calhoun, once more featuring the superintending spirit of George Washington.

Here is how the mysterious, morale-boosting McClellan dream unfolds:

“‘I could not have been slumbering thus more than ten minutes,’ said the General to an intimate friend.”

Someone bursts through the door to his room.

“General McClellan, do you sleep at your post?” The voice addresses him in a “commanding and even terrible tone,” paralyzing the dreamer, and the voice repeats the question. The paralysis slowly lifts, and McClellan rises to find a map spread before him. He calls it “a living map,” which presents an “immense scene”: the whole of the United States, from the North Atlantic to the Gulf of Mexico.

The voice, now called “apparition,” approaches to within six feet of him. The dreaming McClellan strains to recognize him, but perceives no more than “a vapor, a cloud, having only the general outlines of a man.” Next, he receives his orders: “Look to the Southward!”

The “living map” reveals a blockading squadron “looming up” under a bright moon. The general follows with his eyes the harbors and forts, hills and valleys, “every sentinel, every earthwork.” In revealing all, the ghost is giving him a decisive advantage over the rebel forces. As he takes in the prospect and conceives a counterstrategy, McClellan hears: “Tarry not; your time is short.”

The “vapory mentor” at last reveals himself as “the glorified and refulgent spirit of Washington, the Father of his country, and now a second time its saviour.” McClellan, as the yet untested general, can hardly believe who it is he is seeing: “Like a weak, dazzled bird, I sat gazing at the heavenly vision.” General Washington, with his “saving arm,” had come to “raise up” his embattled country, anointing McClellan as the man to enact his will. Lest providential purposes be deprived of their full mystery, the broadside concludes: “The future is too vast for our comprehension; we are the children of the present.”15

One member of McClellan’s staff, twenty-two-year-old George Armstrong Custer, helped draw up maps and occasionally ascended in a reconnaissance balloon over the Virginia countryside. “I am not a believer in dreams,” he wrote to family in Monroe, Michigan, echoing the skepticism of so many others. “However I must tell you about my dream last night.” Someone had called him from his tent to view a balloon in flight. He took field glasses and focused them on a pair of ladies from Monroe, who were seated in the basket of the balloon. “I told the men who had charge of the balloon to ‘let me go up too.’ They consented. I reached the balloon in some manner unknown to me but my friends had gone, much to my disappointment.” Custer’s was that species of dream in which thought travels back in time to a lost familiar setting—compelled by desire for a happy reunion with loved ones, yet bound by the exigencies of the moment.16

George McClellan was all over the news for the first year of the war. It is not surprising, then, that an aging Bostonian, in no shape to serve in the army, spent a troubled sleep “carrying important despatches to McClellan, of which the bitterness in his mouth formed a part.” McClellan’s demands gave the man a headache that would not go away.17

The same was true for President Lincoln, who found himself verbally abused by the real George McClellan—an overconfident underperformer who did not live up to all the hype. Lincoln, who had hired him, now fired him. It could also be said, of course, that the saintly Washington had erred in choosing General McClellan, instead of Ulysses Grant, to visit in the night.

Like the unnamed Bostonian, nearby Concord’s number-one celebrity, Ralph Waldo Emerson, read and reacted to war news. In September 1861, after learning of an early Union success in North Carolina, he had what he called “a pictorial dream fit for Dante.” In it, he was delivering a talk somewhere. But for no particular reason, he had trouble staying awake during his own address, at which point he somehow found himself in a house he did not recognize. It was a new house, “the inside wall of which had many shelves let into the wall, on which great & costly Vases of Etruscan and other richly adorned pottery stood.” The wall was unfinished and seemed about to fall apart. “Then,” Emerson records, “I noticed in the center shelf or alcove of the wall a man asleep, whom I understood to be the architect of the house.” The dreamer called out to his brother and pointed to the sleeping architect. At this, the architect arose, “& muttered something about a plot to expose him.” When Emerson awoke, he compared the interlocking dreams and posed wryly: “What could I think of the purpose of Jove who sends the dream?”

This one was a highly individualized drama with plenty of bizarreness, the dreamer frustrated by the sapping of his energy. He is unhappy to discover that the unfinished house is not as solid as it appears on first inspection. One who might supply answers—the dozing architect—is in his sights. But having the man cornered (or shelved) doesn’t seem to get Emerson anywhere. He is diverted from his purposes, cannot ensure that the valuable art will be preserved, and is basically prevented from accomplishing anything of any meaning. Whether or not it is connected to news of the war, the dream has taken him to a battlefield in the mind, where he is unable to obtain tactical advantage. The Etruscans had a rich warrior tradition, as well as an aesthetic one, which Emerson had written of before.

Emerson’s next journal entry contained a further rumination about present danger: “War the searcher of character, the test of men, has tried so many reputations, has pricked so many bladders.” Generals came and went, were lifted up and measured, tested and tried. Emerson put them in the company of bankers, whose value to the economy was considered only in times of crises. They were really minor actors, pawns, and what they did bore little relation to the natural world. If dreams were absurd, temporally out of step, confused and unmanageable, then warrior chiefs were bred for nightmares; they were prisoners of broken time and manufactured not to last.18

It was hard for Emerson, despite his abolitionism, to make sense of this or any war. For him who wrote in the essay “Nature” that “a dream may let us deeper into the secret of nature than a hundred concerted experiments,” war brushed aside all abstraction. It required too much calculation—it did not tap inspiration.

So he returned to the invisible, where he was more comfortable. Of the mystery of human memory, he wrote early in 1862, “drop one link” in a chain of thoughts, and there is no recovery of the ideas or pictures that preceded in the activity of the mind.

When newly awaked from lively dreams, we are so near them, still agitated by them, still in their sphere;—give us one syllable, one feature, one hint, & we should repossess the whole;—hours of this strange entertainment & conversation would come trooping back to us; but we cannot get our hand on the first link or fibre, and the whole is forever lost. There is a strange wilfulness [sic] in the speed with which it disperses, & baffles your grasp.

Today’s dream researcher would probably say that it was never the brain’s job to retain visible dreams in memory. But for Emerson, a desire to recover what he assumed were “hours” of dream narratives merely underscored his lifelong frustration with their disappearance from the relative certitude of forward consciousness. The more stories he had full access to, the closer he might approach a godlike knowledge of the extent of the mind. That, as much as anything, was Emerson’s pursuit of happiness in a nutshell.19

Unlike Lincoln, who dwelled on the suspicions his mind’s eye produced, Emerson wanted to design a path to knowledge. Implausibly, he hoped to find some way around the process of decay and disrepair. As it is for most of us today, the fragments of those dreams Emerson remembered invariably delivered more questions than answers.

In their letters and diaries, enlisted men, wives and sweethearts, families caught between the warring sides, and hapless prisoners enduring miserable conditions all contributed errant dreams to the emotion-packed literature of these years. To stack up dreams written down on rough paper, to read the passionate appeals of lovers and fragile words of remembrance, is to feel the weight of the war years in a different way.

Adelaide Case of Mecca, Ohio, east of Cleveland, had dreams any teenage girl might have. When she promised herself to a Union soldier, she hoped for a love that would endure. Her beau, twenty-year-old Charlie Tenney, had enlisted in the 7th Ohio in the first year of the war. At the time he went off, the two had not shared intimate thoughts. He had vowed to write, and she to write in turn. But neither had dared to suggest that they would ever be to each other more than a brother to a sister. The spark was lit through the mails in the early months of 1862, when the lonely soldier worked up the courage to take a chance.

“Dear Addie,” he addressed her on New Year’s Day, 1862, from camp in Romney, Virginia (soon to become part of the new state of West Virginia). His first letter was informational. He wanted her to know something about soldiering without vulgarizing the experience. “Some times it happens that inefficient men are placed on a dangerous post,” he explained after a watchful night. “A man was placed on a post near mine, and towards daylight he fancied he saw a man, preparing to make a hostile movement; frightened nearly to death he drew up his musket and fired.” It turned out to be a deer.

In the next letter, he focused on self-improvement. He wanted her to know what kind of man he was. “Over two months ago, I eschewed the use of tobacco,” he wrote. “While at Green Run [on the Virginia side of the Ohio River] I foreswore the practice of playing cards. This I did for my own benefit and character hereafter. Is Addie satisfied with this statement?” He wanted to impress upon her that he would not succumb to the temptations for which soldiers were known. He then ventured cautiously: “Have you passed a happy new-year’s day? and did your thoughts revert once to ‘Soldier boy’ Charlie?” He had shed tears thinking of home, he confessed, reassuring her one last time (in the third person) “that Charlie never was intoxicated in his life.”

“Darling Sister!” was his salutation a week later. “What emotions the writing of that word causes in my heart!” The occasion was his receipt of Addie’s first letter. Whatever it contained showed that she was in no way disappointed with his insinuating tone. She had deemed Charlie’s profession of moral rectitude credible. With her apparent consent, he had graduated from “dear Addie” to “darling sister,” hoping, with Heaven’s help, “that I may be worthy of your love as a brother ought.”

Four days later, he picked up his pen again, already pushing for something stronger than brother-sister. And with hardly a prefatory statement, he declared his love outright. “Do not think me presumptuous, Addie if I say I love you. Do not discard me from your thoughts.” The young soldier laid his heart bare: “With you now rests my happiness. Shall I be happy or the reverse? Do you ask me to wait until you become better acquainted with me? I do not ask or expect that on so short acquaintance you shall decide forever.” Later in the month, with no answer as yet received, he appealed a second time: “Allow me to love you.” And he signed the letter, “Your Charlie.”20

Most of this had transpired within the single month of January. By Valentine’s Day, she was his. He called her letters “angel visits,” and she did the same. In her tiny handwriting, he became “Charlie my darling.” He asked her to send a photograph. When too many days passed between letters, she, as much as he, grew despondent, until the “messenger of love” arrived at her front door in Mecca. Addie was still in school. It was a single classroom containing fifty “scholars,” as she called her classmates, who ranged in age from four to twenty. She had turned eighteen. When the teacher wasn’t paying attention, Addie stole time to write to her soldier boy. And when she counted on a letter and one did not come, she feared he had fallen ill.

Pretty soon, her imagination spiraled out of control. “Oh! I had such a strange dream last night,” she told him. “I shudder even more when I think of it. You were lying ill and delirious where I could both see and hear you. You were calling for me and yet I could not go to you. I struggled long earnestly and in vain but there seemed some great obstacle between us which I could not surmount.” The obstacle, we can assume, was the irregularity of mail delivery in a time of war; but in a dream the rational explanation is replaced by the fantastic—in Addie’s case, it was the presence of personal enemies:

There were all whom I had ever had the least feeling of anger toward mocking me. One thing makes it almost laughable. Col. Tyler [Charlie’s unpopular commander] was one of them. I awoke completely exhausted and—do not laugh, dearest—weeping. Be assured my darling, there was no more rest for me. Why bless you dearest. I have not recd a letter from you for two weeks, and it is no wonder that such dreams as the above come to disturb me, when you, before, have written so often. Why: I believe the tortures of the rack can be nothing to the imaginings of such dreams.21

Swearing love for each other had taken place in an instant and then escalated quickly, making Addie sensitive to the point of obsession. On March 1, she penned a panicky note: “Have I offended you the reason that you do not write?” Again, on March 23, “Do I not deserve—am I not worthy of a letter from my idol?” Her stationery was marred by a round, dark stain: “This is not a tear,” she assured him, adding: “I hope my tears are not quite so black as that ugly spot.” It turns out he had taken part in the Battle of Kernstown, in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, on the twenty-third, where he was wounded in the only action that saw Confederate General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson suffer defeat. Charlie recovered and went back to active duty.

On Independence Day, 1862, from Alexandria, he informed Addie that he had tried and failed to secure a leave of absence. He would not be able to return to Ohio to see her. It was not only his request that was denied—all furloughs were prohibited. He urged her to take heart. “I have a definite foreknowledge,” he said, “that your prayers shall be answered.” Though “the green earth in many places is saturated with the blood of the thousands who have fallen,” he would return to her.

They wrote at least one letter per week, generally more than that, for the balance of the year. “I am loved. Thou art my betrothed,” he gleamed that fall. In January 1863, having just heard from another Ohio soldier that Charlie had “suffered a relapse” under primitive camp conditions, Addie sent him one more dream, and as an interrogation of her emotions it was a predictable one:

In my dreams I was with you last night. I went to sleep wishing that I could fly to you. I had no sooner fallen into a gentle slumber, than I was lifted from my bed, and wafted far far away, over mountains, hills, rivers, cities and so on on on till at last I found myself in a dark comfortable room surrounded by men. Some were lying on rough beds others walking around as if tired of life and wished to walk into eternity.

She asked about, attempting to gain a better sense of her surroundings. A man explained to her that she had come to a military hospital. She was surrounded by badly wounded soldiers.

Mentally I asked if Charlie was there and began searching. Earnestly I gazed in each face hoping to see one familiar glance one loving one but vainly, until I looked in one corner and noticed a rude couch of straw occupied by my Charlie. It needed no second glance to convince me . . . his face animated and his blue eyes beeming with joy as he asked, “Have you come?” I flew to thee darling and awoke.

Letter after letter, they tried to sound confident. She told him that she trusted “a bright and happy future is before us.” He guaranteed his safe return, if she just trusted in God. But on June 14, 1863, as Robert E. Lee was clearing the Shenandoah Valley and heading north toward Pennsylvania, Private Charles Tenney of the 7th Ohio Infantry died at Harper’s Ferry. His comrades would move on to Gettysburg and perform poorly there. Back in Mecca, Ohio, barely nineteen, Adelaide Case became another of the heartbreak kids.22

Louisa May Alcott did not have to dream of visiting the wounded. Toward the end of 1862, she volunteered at the Union Hotel Hospital in Washington, D.C. On any given day, the unmarried thirty-year-old nurse was surrounded by hundreds of men, more of them made worse by the noxious air and circulating disease than by the gaping wounds they received on the battlefield. She sponged clean these maimed male bodies, wrote letters on behalf of some of the convalescents, and did whatever else was expected of her as a never-ending stream of groaning, mud-soaked patients arrived in horse-drawn ambulances.

After just a few weeks, the nurse herself took ill with what was later determined to be typhoid. In her delirium, she experienced “strange fancies,” as she called her dreams, the most peculiar of which Louisa May recorded in her journal. In one of these, she had married a “stout, handsome Spaniard” with “very soft hands” who urged her to “lie still” and was otherwise uncivil toward her. In another, she found herself visiting heaven, “a twilight place with people darting thro the air in a queer way. All very busy & dismal & ordinary.” In a third vision, she was “hung for a witch.” And least improbably of all, she saw herself “tending millions of sick men who never died or got well.”

It was while she was at the Union Hotel Hospital that Louisa May Alcott received word from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper that she had won a $100 prize for her short story about a strong-minded woman who aimed to avenge herself after the man she loved had withdrawn his affection. Publishing under the pseudonym of A. M. Barnard, the war nurse kept her authorship of this fantasy piece a secret from Bronson Alcott, her emotionally demanding (some have said emotionally abusive) father. In mid-1863, she published Hospital Sketches in the abolitionist press and earned high acclaim. After struggling for years, and acting the supplicant to editors, it had taken nightmares to establish her in publishing circles. The deeply committed author would then be catapulted to greater commercial success after the war with her breakout book, Little Women.23

As the rebel government was first assembling in Montgomery, Alabama, another committed individual, Thomas R. R. Cobb of Athens, Georgia, had a peaceful dream. The younger brother of President James Buchanan’s secretary of the Treasury (who was just then helping draft the Confederate Constitution), Cobb was one of the most ardent of fire-eaters in the lead-up to war and the author of a treatise on slavery law. Awaiting the inauguration of Jefferson Davis and ecstatic about the South’s prospects, he wrote home to his wife, Marion: “I dreamed a precious dream about you last night and you were so good, so kind, so sweet, but when were you otherwise?”

Cobb believed in southern values and in the southern family. He slept easily at night. But as a brigadier general in the Army of Northern Virginia, his gentle dream of a future of quiet domesticity faded fast. He saw plenty of death and destruction before his final engagement at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, where an exploding artillery shell tore up his leg. As Louisa May Alcott tended to Yankee soldiers wounded at Fredericksburg, Cobb bled to death, shy of his fortieth birthday.24

“A Singular Prophecy,” declared the Mobile Advertiser in the early spring of 1862. “Its truth is vouched for by a reliable officer in the army.” The story was pretty straightforward: in Pensacola, Florida, “a soldier in the Confederate service fell into a long and profound sleep, from which his comrades vainly essayed to arouse him. At last he woke up himself. He then stated that he should die the next afternoon at 4 o’clock, for it was revealed to him in his dream.” But the dreamer did not stop there, informing his hearers that a massive battle would take place in April of that year, and by May, miraculously, “peace would break upon the land.” His prophecy attracted the newspapers of the region when the soldier died on schedule, leading the Advertiser to ask whether the balance of the prophecy would soon be realized. The last line of the article was a simple suggestion: “Let believers in dreams wait and see.”25

The Confederate soldier’s “singular prophecy” turns out to be plural, because as the fighting intensified, newspapers on both sides regularly featured stories of soldiers dreaming of specific dates when the war would conclude. As though it had a legitimate news item on its hands, the Saturday Evening Gazette of Boston matter-of-factly stated on April 25, 1863, that “the dream which an artilleryman at Fort Warren [Boston] and a member of Hawkins’ Zouaves [a New York outfit] both had six weeks ago, fixing April 23 as the date of Peace has not been fulfilled.” The long-running Richmond Examiner, alluding to the “old women, old men, and young maidens telling their dreams and prophesying the close of the war,” added to the existing stock of rumor with the dream of a soldier in General George Pickett’s division: “He dreamed that he laid down and slept for twenty years—seven more than old Rip Van Winkle snoozed—and that when he woke up, he was lying near Hanovertown [Virginia], General Lee in front of him, with a corporal and four men, waving his sword and crying out, ‘Come on, men, let’s finish up this fight anyhow.’”26

We do not know the fate of the soldier who saw the war continuing another twenty years, but we do know that General Pickett himself wrote home to his wife about “a beautiful dream” he’d had, and apparently the missus was of a similar bent. It pained him to have to instruct her in bearing up to the reality each love-filled dream tried to deny. “While its glory still overshadows the waking and fills my soul with radiance,” he wrote of his own, “You know, my darling, we have no prophets in these days to tell us how near or how far is the end of this awful struggle.”27

Where were people in the Deep South getting their ideas about dream life? To judge by newspaper coverage, one regular reference work was The Anatomy of Sleep by Dr. Edward Binns, first published in 1842 and still considered a highly reputable source twenty years later. At the outset of his book, Binns described sleep as “the art of escaping reflection.” Under normal functioning, he said, imagination, memory, judgment, locomotion, and voice were all “suspended” in sleep. At other times, imagination, memory, and judgment remained active, while locomotion and voice expressed themselves in a sleep “agitated” by dreams.

Retreating ever so slightly from the traditional insistence that dreamless sleep was perfect sleep, he wrote: “Sound, or heavy, or dull sleep is not always an indication of health.” Having studied the dreams of historical figures, and the interpretive use to which they were put, he concluded that great men had great dreams (and knew what to make of their content). He counted on his readers to recognize familiar faces in their dreams: angels and devils, and past giants such as Julius Caesar. Binns allowed that certain dreams accurately predicted. In late 1860, the Baton Rouge Daily Gazette and Comet printed “A Strange Dream,” citing chapter and verse from one that ended in shipwreck—a dream extracted from Dr. Binns’s Anatomy of Sleep.28

Binns, like Professor Lewis, took an interest in thought that came to the dreaming mind in musical form. “Who has not dreamed of listening to beautiful and melodious music?” he posed. If dreams were “a sort of delirium,” he went on, defaulting to medical theorists of the prior century, nightmares were warning signs of danger, an automatic association triggered by the body to isolate an ill or defective organ.

Feeling most comfortable when he went over old territory, Dr. Binns reaffirmed the neurological alliance between dreaming and insanity. Only his descriptive vocabulary sounded different: “Maniacs are inundated with a flow of thoughts, a superabundance of ideas, and a catenation of impressions which invert order, escape arrangement, and defy control, exactly similar to images in dreams.” If the reading public was amenable to lively language, the medical establishment continued to behave conventionally through the Civil War era. When it came to dreaming, the issue that seemed to divide the early nineteenth century’s pious doctors from their mid-century successors was the extent to which they entertained their prophetic potential. Nearly all subscribed to prophecy when it pertained to biblical times, but the verdict had yet to be rendered on the supernatural in their present.

Dr. Binns ended his book where he began, defining sleep as the body’s way of “escaping reflection,” giving needed rest to the thought process. “Sleep,” he said, “is not a negative, but a positive state of existence; and differs from death which is a negative quality, in this: that death is the total absence of sensation, voluntary motion, assimilation, and all the vital phenomena.” Civil War soldiers spoke of angels and comforted themselves by believing that God was the author of a plan for all human experience; meanwhile, noncombatants across the country fought isolation and disillusionment with the tools at hand. In trying circumstances, pleasant dreams could be counted among the divine mercies.29

When the war began, sixteen-year-old Clara Solomon of New Orleans was a staunch supporter of the new Confederate government. Her father, Solomon Solomon—“the dearest and best of fathers”—was a merchant supplying clothing to the army. In June 1861, when he was away on business, Clara worried for his safety. One night, after their household slave, Lucy, “lowered the gas and bade me good night,” she lay in bed trying to lull herself to sleep. She heard her father’s voice, and she pictured her older sister and herself on board a steamboat, accompanying him to “some distant place.” Then, sitting on a sofa, Clara was accosted by some drunken men. She fled their presence, but in evading their clutches, she was, she said, “so exhausted that I fell down, and the shock awoke me.”

At four in the morning, she heard screams coming from Lucy’s room. Clara roused her mother and sisters, and they all went in to check on the servant, who protested that it was not a nightmare at all, but menstrual cramps that had prompted her outburst. “Ma administered the available remedies, which afforded some relief,” and they all enjoyed a long moment of laughter at Lucy’s expense.

The train of events is informative. An anxiety dream, remembered because a slave cried out in the depths of night, offers a glimpse of the moving images and voices in the diarist’s head. Clara invokes words of fear—“pursuit,” “evading,” and “accosted”—in her dream telling. In the same diary entry she repeats the words “scream” and “frighten.” A friend’s young daughter had recently died a shocking death from a “pernicious fever,” which led Clara to write of the “spotless little soul” having “winged its flight to another world.”

The lexicon of this young diarist is representative of the mid-nineteenth century, when the “winged flight” metaphor was repeated in multiple dream descriptions. Dreams were seen as a kind of flight that spirited the dreamer away and opened up another world. The associated realms of death and dreams were awe inspiring and remained beyond human comprehension—ill defined and unresolvable for assimilated Jews like the Solomons as much as for their Catholic neighbors.

The year 1862 brought the war to Clara’s doorstep. Of the relatively few dreams she recorded, one that summer was the bearer of unmitigated pleasure. In it, two “dear persons,” both male, “figured so conspicuously” that she refused to confide, even to her diary, what had transpired in her mind. “Oh! dreams are unpleasant in whatever aspect we near them,” she wrote, complaining that her hopeful fantasies caused almost as much sorrow and disappointment as her scarier dreams did. “How sad I was to wake & contrary to my thoughts find myself in my own bed!”

She turned to the approaching Fourth of July, which she hoped to celebrate—“but oh! how differently from former years.” The Confederate cause was sinking in the bayou, as Union forces under the iron hand of General Benjamin Franklin Butler occupied the South’s most vibrant commercial port. “The Beast,” as some called Butler, had just ordered the hanging of a Confederate patriot for hauling down a U.S. flag. Beyond this, he was hated for treating uncooperative southern women much as prostitutes were treated, decreeing a night’s imprisonment for any female who was so unladylike as to insult a Union officer.30

Bald and pudgy, Butler was a family man as well as a warrior, a husband who made fun of the dream-book genre and his wife’s credulity when he felt like needling her: “How do you do this fine morning?” he gaily taunted in a letter home. “You are not yet up, eh! Have you slept well? Did you dream of me? Or did you dream of snakes, having eaten salad over night?” Evidently, he knew how to strike a nerve, to judge from letters later in the war, when the “Beast’s” wife, Sarah, wrote to their daughter with inauspicious premonitions regarding the family: “I am worried every night for fear something should go wrong at home. One night I dream that Paul is drowned, another that Benny is dead. Nothing as yet, that is wrong with you. But tonight I may have some fearful dream of you.” And then, after a pause: “I have done eating their odious soups, and various other abominations. Coffee, bread, eggs and milk make up my diet. This will do away with dreams.” The old notion that indigestion caused nightmares remained standard thinking. Evidently, General Butler could not dissuade his wife.31

As Clara Solomon and the rebels of south Louisiana were dealing with the reverses of war, another young woman, Lucy Breckinridge of Grove Hill plantation, near Fincastle, Virginia, worried for the safety of her several brothers who were away fighting the Yankees. Johnny, the younger brother who was closest to her in age, died in June 1862, at the very bloody Battle of Seven Pines, outside Richmond. The image of him in life, and the pain of his untimely passing, returned to her mind often.

One winter’s night, early in 1863, after a week without caring to compose her thoughts, Lucy was lured to the blank page of her diary (“this dear, stupid old book,” she bemoaned) in order to debate a vision. “I dreamed of peaches last night,” she wrote, “and upon waking lay in bed thinking of Dolly’s mournful interpretation: ‘to dream of fruit out of season is trouble without reason,’ and in my own mind trying to establish the fallacy of it.” Dolly was her slave, and Lucy willed herself to resist superstition gleaned from dream-book notions, to which many of the slaves were drawn. A second brother, the aptly named Peachy Gilmer Breckinridge, rose to the rank of captain and not long after died in battle, his body never recovered.

Dreams fade in the daylight, and she never wrote in her diary but at night, so we cannot go deeper. As the war ended, and only a few months into her marriage to a Texan, Lucy Breckinridge, of an old and respected Virginia lineage, died of typhoid fever. Life was short and her Civil War a sad tale of peaches and dreams.32

Here’s what does come through, at least. When she told her peach dream to her slave Dolly, Lucy had gotten in return a simple formula for interpreting it. In a similar manner, an Arkansan, born a slave, told an interviewer later in life: “When you dream of the dead there’s sho’ gonna be falling weather.” To this day, among eastern North Carolina’s African American communities, belief has persisted (if in a less structured way than in West Africa) that ancestors communicated directly through dreams, especially at moments of emotional crisis. Said one black North Carolinian: “The night before I had a mild heart attack, I dreamed of my grandmother.” Her voice was loud and firm, and commanded, “Get control of yourself boy.” Ancestor dreams brought news of impending death and at other times served to allay fears and calm the nerves. The common denominator was the strong sense that no one is entirely self-made, that human beings are products of the past and cannot be detached from those who came before.33

As one might imagine, the dreams of the enslaved carry a special poignancy. Under the institution of slavery, families were routinely torn apart, fathers and mothers separated from their children, if not as punishment then simply owing to perceived economic necessity. Charles Ball, sold by his Maryland owner and brought south to Georgia, had a dream en route:

I thought I had, by some means, escaped from my master, and through infinite and unparalleled dangers and sufferings, had made my way back to Maryland; and was again in the cabin of my wife, with two of my little children on my lap; whilst their mother was busy in preparing for me a supper of fried fish, such as she often dressed, while I was at home. . . . Every object was so vividly impressed upon my imagination in this dream that, when I awoke, a firm conviction settled upon my mind, that by some means, at present incomprehensible to me, I should yet again embrace my wife and caress my children.34

While it may be that songs inspired by biblical lessons kept hope alive, literal dreams tended to keep slaves on edge. Francis Federic, held in bondage in both Virginia and Kentucky, had a dream shortly after his escape across the Ohio River to freedom in 1855. He could not accept that the nightmare was over: “Two or three nights in succession I dreamt that I was taken by my master, and all the details of the capture were so vividly depicted in my dreams, that I could scarcely, when awake, believe it was all a vision of the night.”35

Masters and slaves were often traveling companions, and every once in a while, a white man of privilege revealed just how intimate their conversation could be. “My faithful servant Juba is sick,” the irrepressible Virginia congressman John Randolph, a master of the Old South, wrote to a friend. “I heard him in his sleep cry out ‘I wish I and master were at home!’” Dream or delirium, the incident reminds us of what happens when we convert the clash of cultures into a simple story of good versus evil. The paternalism Randolph lived by fed arrogance, but it also required kindness. He and Juba slept within earshot of each other, and in his own way, he believed they had made common cause.36

The cult of the “good master” married to a sense of southern honor thrived because slavery could not otherwise be defended. In dream terms, one telling symbol of the underlying trauma appears in a book published in Philadelphia in the mid-1830s, as tensions between North and South were rising, but not yet full-blown. In A Concise View of Slavery, a chapter with the heading “The Slave Whipped to Death for Telling His Vision” related the shortened life of a slave named Ajax, living in Leesburg, Virginia. According to the author, Ajax had had “a very remarkable dream or vision, which of the two I cannot pretend to determine . . . , the substance of which was . . . he conceived himself transported into the midst of the infernal regions [and] saw his master and overseer . . . suspended by their tongues.” Ajax’s master “hated him for his dream” and reacted impulsively. Either unwilling or unable to distinguish between unsuppressed imagination and active subversion of power, the slave owner gave his slave the ultimate punishment.37

Just after President Lincoln delivered his immortal Gettysburg Address, one of his generals, James A. Garfield of Ohio, spoke in Baltimore about the fighting spirit of the men under his command, and he left no doubt why the war was being waged. “Slavery is dead,” he proclaimed, “and only remains to be buried.” He had read Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1852; three years later, while he was courting his wife, Lucretia, she wrote to him of the effect that Stowe’s “sad thrilling story” had on her spirit—it framed a passionate correspondence in which both parties recurred often to the language of dreams and reveries. He posed to her, for instance: “Did you ever dream in a winter night of the lovely summertime?”

Garfield was a man of action who devoured adventure stories and biographies and would later become himself an exemplar of self-made American manhood. Portraying the slave-owning generals of the South as pampered boys born with silver spoons, the brigadier general roused Baltimoreans with the boast that his “mudsills,” common farmers and shopkeepers of the New West, were crushing the fatuous “dream” of those “frantic men” of the effete South who had divided the nation. So, in romancing his future wife, he approved of literal dreams; and in firing up his men and their supporters back home, he applied the old, derisive epithet of dreamers as losers. A bit later in the war, as we shall see, Garfield was to have less success convincing his wife that her dream of him cavorting with other women was a mere figment of her sleeping imagination.38

“The Soldier’s Dream” was a poem that made the rounds often and from early in the war. Originally penned by the late eighteenth-century Scottish poet Thomas Campbell, it told of a war-wearied husband and father who transported himself home in a dream that repeated three times in one night. His loved ones were there to embrace and console him and to beg him to stay. All was well for the soldier until sorrow returned with the dawn, all his nostalgic feeling dissolving into the ground where he lay—as “the voice in my dreaming ear melted away.”

The old pastoral dream was a potent anthem for the romantic youth who put themselves in harm’s way in order to defend their ideals. Ohioan Charlie Tenney composed a love letter to his “dearest Addie” on stationery that reprinted Campbell’s poem. Above its title, the doomed private scrawled: “Is not this beautiful.”39

Soldiers’ dreams ranged from hot pursuit of a visible enemy to sweet fantasies of being back home with family. As often, they deplored not being able to dream at all, mired as they were (often literally) in the places where their flimsy tents were pitched. A Union lieutenant who was part of an amphibious landing on the northeast coast of Florida in 1862 spoke clearly in his sleep, and his comrade reported him “evidently chasing a rebel in his dream.” A Massachusetts man involved in the long siege of Vicksburg wrote in his diary on July 6, 1863, two days after the city fell to Union forces, that to “lie down to pleasant dreams” was too much to hope for, especially after an overnight thunderstorm, with no shelter but a rubber coat. Twenty-year-old Thomas Christie of the First Minnesota Light Artillery, stationed in the same Mississippi River town some months later, dreamt about his day job: “I ought to have been quietly sleeping last night,” he wrote home, “but according to my tent-mate this is what I was saying: ‘By detail, load; two, three, four! Sponge; two, three, four! Ram two, three! Ready, fire!’” And then, turning to a soldier he was in charge of, he continued issuing orders: “Bend that knee a little more; hold your shoulders square to the front.” He told his father: “Nothing is so exciting as working a gun in action. The sound of the discharge almost raises us off our feet with delight.”40

Post-traumatic stress disorder was not part of the Civil War vocabulary, but it is suggested in the account of a soldier who had been wounded in the foot and was recuperating in Philadelphia. As he was waiting for a furlough to visit his sick wife and children in Maine, he had two related dreams: in one, he lost an entire leg and his face was badly scarred; he feared his family would not be accepting of him, but as the changed, crippled man hobbled up to his front door, he was wildly embraced by his wife and welcoming neighbors. In the second dream, the war was over and he was coming home a hero, but when he arrived, his wife greeted him coldly, and even his children looked sad and disappointed. He asked his wife for an explanation, and she “looked me right in the face but wouldn’t say a word.” Somehow he figured out that she was perturbed because he had fallen in with some unprincipled men and had neglected to write to her. “While she was looking at me this way, and I was trying to hide my face,” he concluded nervously, “I all of a sudden waked up.”41

One of the most bizarre of violent dreams reported during the Civil War did not have anything to do with the fighting. In Medina, Ohio, around the time of Gettysburg, newspapers reported that “a boy in the village” dreamt of a nearby triple murder. At first, when he woke his parents in the middle of the night, his father laughed it off. By morning, as news of the actual slayings circulated in Medina, “the boy dreamer,” as he was known, supplied authorities with details not only of “the disposition of the contents of the room” where the victims were, but also the face of the killer, which he described “minutely.” A man who fit the description, twenty-three-year-old Frederick Streeter, originally from Vermont and a Union Army deserter, was arrested. But the story did not end there: after escaping from prison and eventually being recaptured, he was found guilty of the crime and swung from the gallows in early 1864.42

Women on the home front had their share of prophetic dreams. Georgia-born Sarah Wadley relocated to Vicksburg before the war and was living in Louisiana when, in the summer of 1863, she had a dream, “beautiful and as vivid as reality,” in which a brilliant star, “as large and round as the moon,” rose above the trees outside her home. It sparkled like a diamond and expanded to spell the word Nebraska, standing out clear and distinct against the dark blue. She thought that her visionary experience related somehow to the future of the country. Next the word “Massachusetts” was spelled out, and below, the French word “epouvantee,” which Sarah somehow found uplifting. As her visions dissolved, she felt it was near dawn, and “the whole yard was crowded with negroes gazing awestruck”; they began to disperse, and her grandmother’s pastor from Savannah, though already “three years in the silent land,” drove up to where she was. “Without speaking I put my arm in his and walking into the house . . . , I spoke to him of the marvellous sight which he had also witnessed.” Then she awoke, went to her bookshelf, and looked up the French word she had seen in her dream, the meaning of which—“terrified”—she had not known until that moment. She thought it might signify official French recognition of the independence of the Confederacy. Underscoring a proneness to wishful thinking, Sarah concluded: “This vision gives me new confidence, it seems to me that God has revealed to me that we will prevail through his mercy.”43

Of this species of dream, we can add that of seventy-eight-year-old Eleanor Meigs, a member of a pacifist Shaker community in southwestern Kentucky that was caught between the northern and southern armies and strove to maintain friendly relations with both. In April 1864, as General Grant was gearing up for his devastating campaign against Lee in Virginia, she woke from a dream around midnight: “I appeared to be traveling with my guide who took me to Washington City & into the White House. I saw a number of soldiers, my guide who was a brother [Shaker] spoke to them in a loud and commanding Voice—told them to be wide awake. He then told me that there were ten times as many soldiers around the City of Richmond as were here. . . . I marveled at this and began to look at how many there were.” She was predicting the fall of the Confederacy a year ahead of schedule.44

Not surprisingly, sweet dreams filled letters to and from the battlefront. At times, men hardened by army life found themselves amazed by the sense of transport as they slipped from a resolute, watchful consciousness into the blissful abstraction of the night’s memory probe. From Meridian, Mississippi, a twenty-three-year-old Confederate soldier wrote to his cousin and future wife, thanking God for a hopeful vision he received while asleep: “Oh! I had a dream last night,” he cried, “a dream of happiness without alloy, and its spirit breathings linger around me yet. My soul thanks the great Giver of all good that He has endowed us with the faculty of dreaming, that the overwrought, wearied soul may wander a season, through the mystic regions of the Dream-land . . . of another and happier world. I thought it was spring-time.”

Virginian Willie Brand wrote to Kate Armentrout, the woman he was courting, with understandable apprehension, given the extent of his deployment: “I had a very strange dream the other night[.] I drempt that me & you had fallen out & Rachel Crobarger was interseeding for me.” Below his signature, the insecure soldier, doubting how long his girlfriend’s patience would last, exhorted: “You will please never show this to anyone.” She must have replied in a thoroughly soothing way by deploying a dream of her own, because he wrote back to her: “My darling Kate you said your face could not ware a joyous smile, untill you could behold my face. . . . That dream of yours oh that it was a reality.”

From east Tennessee, Lieutenant Colonel William McKnight, a cavalryman who hailed from Ohio, wrote to Samaria, his wife of eight years, of the world that stared him in the face in the light of day: “The Rebs are about ten thousand strong in front of us . . . , creeping up on our pickets & fireing.” But all this disappeared from his mind when he fell asleep: “I dreamed a sweet dream about you,” he purred. For that short time he saw her and their children sitting before him “on bended knee,” only to wake to the realization that it was all a “Delusion,” and he could do no more than bid her kiss their little ones and pray that he would make it back. “Let the memory of the past and hopes of the future sustain you,” he wrote in more than one letter home. McKnight was killed in action in Kentucky only months later, age thirty-two.45

Such pathos was not missed by the columnists of the day. Under the heading “A Beautiful Picture,” the Cleveland Plain Dealer offered a painfully simple, and very visual, example of the true cost of war to thousands of families. The story centered on an ambrotype—a photograph, related to the daguerreotype, in which the image is exposed on a glass sheet and encased in a protective folder. There were “three charming little children” in the picture. They were nameless, and all efforts to locate them came up empty. What mattered, though, was where the ambrotype was found: “Amidst the awful debris of the Battle of Gettysburg, a soldier was discovered, in a half sitting posture, stricken with death, grasping in one hand the ambrotype. . . . It was probably taken out by the dying soldier after the fatal bullet had struck him down.” As an antiwar symbol, this one hardly needed a caption.46

Americans received no real respite from the carnage, as the frozen, faded images produced by the likes of Matthew Brady attest. But a different death stared prisoners of war in their gaunt faces. The notorious Andersonville camp in southwestern Georgia was not constructed until after the tide had turned against the Confederacy. But conditions fast deteriorated, and nearly 30 percent of the thousands of Union men interned there died of starvation or disease before war’s end.

Two imprisoned diarists, who lived to tell their tales, give some hint of the nature of their dreams while in confinement. John Northrup related a gruesome chronicle of mass deprivation, of hungry men exhibiting symptoms of scurvy (“the flesh of their limbs has become lifeless”). He detailed the “strange dream” of one of his fellow sufferers, who first glimpsed a hellish foreground and then a better beyond. In the diarist’s words, he “beheld immediate conditions, and the blackness and terror of the supposed ‘river of death’ which soon brightened into a bordering stream, before which all misery, terror and darkness vanished, and he beheld the mystic world. He regarded this as a prophecy of change soon to come to him and said he had no terror of what might come; it had given him strength ineffable.” Theirs was a cheerless (if not friendless) death camp, and the dream was this prisoner’s saving grace.

In December 1863, Andersonville prisoner John Ransom, a Michigander captured in east Tennessee, wrote: “Dream continually nights about something good to eat. . . . A man froze to death last night where I slept.” The counter positioning of ideas proves that the absurd in life will come into dreams just as easily when life is barely life at all. Still at Andersonville six months later, Ransom pursued a deeper understanding of the absurd. It was “funny” to him that men were attempting to escape by pretending to be dead so that they would be carried beyond the prison walls with the other dead, only to “jump up and run” as night fell. It had worked for some, because “dead men are so plenty that not much attention is paid.” The next day, he found something else “funny” that might not have been under other circumstances: “Had a funny dream last night. Thought the rebels were so hard up for mules that they hitched up a couple of gray-back lice to draw in the bread.” Surprised by how robust he was after a half year of incarceration in sandy soil “alive with vermin,” the diarist thought ahead to the hottest months and simply shrugged: “Every man will die, in my estimation.”47

When General Ambrose E. Burnside disobeyed President Lincoln’s instructions in September 1863, the president replied incredulously, “Yours of the 23rd is just received, and it makes me doubt whether I am awake or dreaming.” The war had acquired such surreal ugliness that the commander-in-chief vied as often with his own contradictory emotions as with the actions of his general officers.

He found he had to. Lincoln, so often referred to as “brooding,” was a realist who turned to books and educated himself on military strategy. He presided over the deaths of hundreds of thousands he did not know; and in the midst of it all, his outgoing eleven-year-old son, Willie, wasted away and died of an illness related to poor sanitation. The end of the war did not come until Grant threw his troops against Lee’s for weeks on end, whittling down the rebel army. Lincoln saw a sample of this effort when he crossed into Virginia to view a Union bombardment of the Confederate position toward the end of March 1865.

His secretary of the navy, Gideon Welles, kept a comprehensive diary. On April 3, while all were awaiting the Confederate surrender, Welles recorded what Secretary of War Edwin Stanton said in a cabinet meeting about the behavior of Lincoln’s predecessor, James Buchanan. As a lame duck president in early 1861, waiting for Lincoln’s arrival in Washington, Buchanan (Stanton could not resist calling him “a miserable coward”) believed that the tall, unmistakable Illinoisan was a walking target who would not live to take the oath of office.

On April 10, Welles noted, guns fired a salute to announce the final capture of Lee’s army. On the evening of the thirteenth, fireworks filled the skies of Washington as celebration continued. The next day, the president’s last, General Grant attended a meeting of the cabinet, and Stanton put forward his plan for Reconstruction. Welles noted that Lincoln now expected to hear more good news from General Sherman, still in the field, “for he [Lincoln] had last night the usual dream which he had preceding nearly every great and important event in the War. Generally the news had been favorable which succeeded this dream, and the dream itself was always the same.” Welles asked what the dream consisted of, and Lincoln explained that it related to the element water. As Welles put it: “He seemed to be in some singular, indescribable vessel, and that he was moving with great rapidity towards an indefinite shore.” He had had the same dream before the firing on Fort Sumter and the Battles of Bull Run, Antietam, Gettysburg, and Vicksburg, as well as Stone River (in Tennessee), which, Grant reminded him, was not a victory. Lincoln’s response was to shrug and suggest that Stone River might be an exception, but the fact was, on April 12, he had had the same dream then that ordinarily presaged positive war news.48

According to the president’s great friend Ward Hill Lamon, a few days before this, Lincoln had said, “in slow and measured tones,” and in the company of Lamon and Mary Todd Lincoln: “It seems strange how much there is in the Bible about dreams.” He had counted “some sixteen chapters” in the Old Testament, and “four or five” in the New, that contained dreams. “If we believe the Bible,” Lincoln said, “we must accept the fact that in the good old days God and His angels came to men in their sleep and made themselves known in dreams.” This more or less coincided with Benjamin Rush’s rationale that dreams were once, but no longer, messages from the divine. “Nowadays,” Lincoln reputedly added, “dreams are regarded as very foolish, and are seldom told, except by old women and by young men and maidens in love.”

In Lamon’s telling, “Mrs. Lincoln here remarked: ‘Why you look dreadfully solemn; do you believe in dreams?’”

“I can’t say that I do,” Lincoln is meant to have answered her. “But I had one the other night which has haunted me ever since.”

As he began to explain the dream, his wife grew more concerned, and he regretted having broached the subject. While outwardly denying the significance of dreams and visions, she forced him to provide as much of the detail as he could recollect. He dreamt, he thought, very soon after falling asleep. He was passing from room to room in the White House, trying to track down a disturbing sound he was hearing—the “pitiful sobbing” of invisible mourners. Arriving at the East Room, Lincoln narrated, “I was met with a sickening surprise.” There lay a fully decorated coffin on a raised platform, surrounded by a military guard. “Who is dead in the White House?” the dreamer asked one of the soldiers. “The President,” came the reply. “He was killed by an assassin.” The mourners again cried out, and this awoke the president from his dream. Or so Lamon assures us.

Lincoln was convinced of the prophetic nature of dreams, but only some dreams. This one, in describing his impending death, may be an embellished version of what actually took place, given the unlikelihood that Mary Todd Lincoln would have to ask her husband at this stage in their marriage, “Do you believe in dreams?” The reader must decide whether the entire vignette should be dismissed on the basis of one tiny clue to its inauthenticity. After relating the assassination dream, Lamon says that Lincoln recited for him Shakespeare’s famous line from Hamlet’s soliloquy: “To sleep, perchance to dream: ay, there’s the rub!”

Regardless of how true to life these sketches are, they make Lamon’s final apologia all the more dramatic. He insists that he specifically warned his old friend not to attend the theater on the evening of the fourteenth. Lamon was leaving Washington for Richmond and obliged Secretary of the Interior John P. Usher of Indiana, another old acquaintance of the president’s, to join him in urging Lincoln not to leave the White House while Lamon was away. They had their audience with Lincoln, who turned to Usher and said of Lamon: “This boy is a monomaniac on the subject of my safety. . . . He thinks I shall be killed.”

If Lincoln truly experienced the disturbing dream of his own corpse lying in the East Room, and not long after jokingly complained to Usher about Lamon’s concerns, some crucial connection has to be missing in Lamon’s narrative. The author frustrates the modern historian by repeating conversations at length, yet failing to provide a proper explanation for the president’s different faces and irreconcilable attitudes. It seems only fitting that we should be left with a mystery.