IT is only half-past four o’clock: there is the faintest blue light of beginning day,—and little Victoire already stands at the bedside with my wakening cup of hot black fragrant coffee. What! so early? . . . Then with a sudden heart-start I remember this is my last West Indian morning. And the child—her large timid eyes all gently luminous—is pressing something into my hand.

Two vanilla beans wrapped in a morsel of banana-leaf,—her poor little farewell gift! . . .

Other trifling souvenirs are already packed away. Almost everybody that knows me has given me something. Manm-Robert brought me a tiny packet of orange-seeds,—seeds of a “gift-orange”: so long as I can keep these in my vest-pocket I will never be without money. Cyrillia brought me a package of bouts, and a pretty box of French matches, warranted inextinguishable by wind. Azaline, the blanchisseuse, sent me a little pocket looking-glass. Cerbonnie, the màchanne, left a little cup of guava jelly for me last night. Mimi—dear child!—brought me a little paper dog! It is her best toy; but those gentle black eyes would stream with tears if I dared to refuse it. . . . Oh, Mimi! what am I to do with a little paper dog? And what am I to do with the chocolate-sticks and the cocoanuts and all the sugar-cane and all the cinnamon-apples? . . .

. . . TWENTY minutes past five by the clock of the Bourse. The hill shadows are shrinking back from the shore;—the long wharves reach out yellow into the sun;—the tamarinds of the Place Bertin, and the pharos for half its height, and the red-tiled roofs along the bay are catching the glow. Then, over the light-house—on the outermost line depending from the southern yardarm of the semaphore—a big black ball suddenly runs up like a spider climbing its own thread. . . . Steamer from the South! The packet has been sighted. And I have not yet been able to pack away into a specially purchased wooden box all the fruits and vegetable curiosities and odd little presents sent to me. If Radice the boatman had not come to help me, I should never be able to get ready; for the work of packing is being continually interrupted by friends and acquaintances coming to say good-bye. Manm-Robert brings to see me a pretty young girl—very fair, with a violet foulard twisted about her blonde head. It is little Basilique, who is going to make her pouémiè communion. So I kiss her, according to the old colonial custom, once on each downy cheek;—and she is to pray to Notre Dame du Bon Port that the ship shall bear me safely to far-away New York.

And even then the steamer’s cannon-call shakes over the town and into the hills behind us, which answer with all the thunder of their phantom artillery.

. . . THERE is a young white lady, accompanied by an aged negress, already waiting on the south wharf for the boat;—evidently she is to be one of my fellow-passengers. Quite a pleasing presence: slight graceful figure,—a face not precisely pretty, but delicate and sensitive, with the odd charm of violet eyes under black eyebrows. . . .

A friend who comes to see me off tells me all about her. Mademoiselle Lys is going to New York to be a governess,—to leave her native island forever. A story sad enough, though not more so than that of many a gentle creole girl. And she is going all alone; for I see her bidding good-bye to old Titine,—kissing her. “Adié encò, chè;—Bon-Dié ké béni ou!” sobs the poor servant, with tears streaming down her kind black face. She takes off her blue shoulder-kerchief, and waves it as the boat recedes from the wooden steps.

. . . Fifteen minutes later, Mademoiselle and I find ourselves under the awnings shading the saloon-deck of the Guadeloupe. There are at least fifty passengers,—many resting in chairs, lazy-looking Demerara chairs with arm-supports immensely lengthened so as to form rests for the lower limbs. Overhead, suspended from the awning frames, are two tin cages containing parrots;—and I see two little greenish monkeys, no bigger than squirrels, tied to the wheel-hatch,—two sakiwinkis. These are from the forests of British Guiana. They keep up a continual thin sharp twittering, like birds,—all the while circling, ascending, descending, retreating or advancing to the limit of the little ropes attaching them to the hatch.

The Guadeloupe has seven hundred packages to deliver at St. Pierre: we have ample time,—Mademoiselle Violet-Eyes and I,—to take one last look at the “Pays des Revenants.”

I wonder what her thoughts are, feeling a singular sympathy for her,—for I am in that sympathetic mood which the natural emotion of leaving places and persons one has become fond of, is apt to inspire. And now at the moment of my going,—when I seem to understand as never before the beauty of that tropic Nature, and the simple charm of the life to which I am bidding farewell,—the question comes to me: “Does she not love it all as I do,—nay, even much more, because of that in her own existence which belongs to it?” But as a child of the land, she has seen no other skies,—fancies, perhaps, there may be brighter ones. . . .

. . . Nowhere on this earth, Violet-Eyes!—nowhere beneath this sun! . . . Oh! the dawnless glory of tropic morning!—the single sudden leap of the giant light over the purpling of a hundred peaks,—over the surging of the mornes! And the early breezes from the hills,—all cool out of the sleep of the forests, and heavy with vegetal odors thick, sappy, savage-sweet!—and the wild high winds that run ruffling and crumpling through the cane of the mountain slopes in storms of papery sound!—

And the mighty dreaming of the woods,—green-drenched with silent pouring of creepers,—dashed with the lilac and yellow and rosy foam of liana flowers!—

And the eternal azure apparition of the all-circling sea,—that as you mount the heights ever appears to rise perpendicularly behind you,—that seems, as you descend, to sink and flatten before you!—

And the violet velvet distances of evening;—and the swaying of palms against the orange-burning,—when all the heaven seems filled with vapors of a molten sun! . . .

HOW beautiful the mornes and azure-shadowed hollows in the jewel clearness of this perfect morning! Even Pelée wears only her very lightest head-dress of gauze; and all the wrinklings of her green robe take unfamiliar tenderness of tint from the early sun. All the quaint peaking of the colored town—sprinkling the sweep of blue bay with red and yellow and white-of-cream—takes a sharpness in this limpid light as if seen through a diamond lens; and there above the living green of the familiar hills I can see even the faces of the statues—the black Christ on his white cross, and the White Lady of the Morne d’Orange—among upcurving palms. . . . It is all as though the island were donning its utmost possible loveliness, exerting all its witchery,—seeking by supremest charm to win back and hold its wandering child,—Violet-Eyes over there! . . . She is looking too.

I wonder if she sees the great palms of the Voie du Parnasse,—curving far away as to bid us adieu, like beautiful bending women. I wonder if they are not trying to say something to her; and I try myself to fancy what that something is:—

—“Child, wilt thou indeed abandon all who love thee! . . . Listen!—’tis a dim grey land thou goest unto,—a land of bitter winds,—a land of strange gods,—a land of hardness and barrenness, where even Nature may not live through half the cycling of the year! Thou wilt never see us there. . . . And there, when thou shalt sleep thy long sleep, child, that land will have no power to lift thee up;—vast weight of stone will press thee down forever;—until the heavens be no more thou shalt not awake! . . . But here, darling, our loving roots would seek for thee, would find thee: thou shouldst live again!—we lift, like Aztec priests, the blood of hearts to the Sun!” . . .

. . . IT is very hot. . . . I hold in my hand a Japanese paper-fan with a design upon it of the simplest sort: one jointed green bamboo, with a single spurt of sharp leaves, cutting across a pale blue murky double streak that means the horizon above a sea. That is all. Trivial to my Northern friends this design might seem; but to me it causes a pleasure bordering on pain. . . . I know so well what the artist means; and they could not know, unless they had seen bamboos,—and bamboos peculiarly situated. As I look at this fan I know myself descending the Morne Parnasse by the steep winding road; I have the sense of windy heights behind me, and forest on either hand, and before me the blended azure of sky and sea with one bamboo-spray swaying across it at the level of my eyes. Nor is this all;—I have the every sensation of the very moment,—the vegetal odors, the mighty tropic light, the warmth, the intensity of irreproducible color. . . . Beyond a doubt, the artist who dashed the design on this fan with his miraculous brush must have had a nearly similar experience to that of which the memory is thus aroused in me, but which I cannot communicate to others.

. . . And it seems to me now that all which I have tried to write about the Pays des Revenants can only be for others, who have never beheld it,—vague like the design upon this fan.

Brrrrrrrrrrr! . . . The steam-winch is lifting the anchor; and the Guadeloupe trembles through every plank as the iron torrent of her chain-cable rumbles through the hawse-holes. . . . At last the quivering ceases;—there is a moment’s silence; and Violet-Eyes seems trying to catch a last glimpse of her faithful bonne among the ever-thickening crowd upon the quay. . . . Ah! there she is—waving her foulard. Mademoiselle Lys is waving a handkerchief in reply. . . .

Suddenly the shock of the farewell gun shakes heavily through our hearts, and over the bay,—where the tall mornes catch the flapping thunder, and buffet it through all their circle in tremendous mockery. Then there is a great whirling and whispering of whitened water behind the steamer—another,—another; and the whirl becomes a foaming stream: the mighty propeller is playing! . . . All the blue harbor swings slowly round;—and the green limbs of the land are pushed out further on the left, shrink back upon the right;—and the mountains are moving their shoulders. And then the many-tinted façades,—and the tamarinds of the Place Bertin,—and the light-house,—and the long wharves with their throng of turbaned women,—and the cathedral towers,—and the fair palms,—and the statues of the hills,—all veer, change place, and begin to float away . . . steadily, very swiftly.

Farewell, fair city,—sun-kissed city,—many-fountained city!—dear yellow-glimmering streets,—white pavements learned by heart,—and faces ever looked for,—and voices ever loved! Farewell, white towers with your golden-throated bells!—farewell, green steeps, bathed in the light of summer everlasting!—craters with your coronets of forest!—bright mountain paths upwinding ’neath pomp of fern and angelin and feathery bamboo!—and gracious palms that drowse above the dead! Farewell, soft-shadowing majesty of valleys unfolding to the sun,—green golden cane-fields ripening to the sea! . . .

. . . The town vanishes. The island slowly becomes a green silhouette. So might Columbus first have seen it from the deck of his caravel,—nearly four hundred years ago. At this distance there are no more signs of life upon it than when it first became visible to his eyes: yet there are cities there,—and toiling,—and suffering,—and gentle hearts that knew me. . . . Now it is turning blue,—the beautiful shape!—becoming a dream. . . .

AND Dominica draws nearer,—sharply massing her hills against the vast light in purple nodes and gibbosities and denticulations. Closer and closer it comes, until the green of its heights breaks through the purple here and there,—in flashings and ribbings of color. Then it remains as if motionless a while;—then the green lights go out again,—and all the shape begins to recede sideward towards the south.

. . . And what had appeared a pearl-grey cloud in the north slowly reveals itself as another island of mountains,—hunched and horned and mammiform: Guadeloupe begins to show her double profile. But Martinique is still visible;—Pelée still peers high over the rim of the south. . . . Day wanes;—the shadow of the ship lengthens over the flower-blue water. Pelée changes aspect at last,—turns pale as a ghost,—but will not fade away. . . .

. . . The sun begins to sink as he always sinks to his death in the tropics,—swiftly,—too swiftly!—and the glory of him makes golden all the hollow west,—and bronzes all the flickering wave-backs. But still the gracious phantom of the island will not go,—softly haunting us through the splendid haze. And always the tropic wind blows soft and warm;—there is an indescribable caress in it! Perhaps some such breeze, blowing from Indian waters, might have inspired that prophecy of Islam concerning the Wind of the Last Day,—that “Yellow Wind, softer than silk, balmier than musk,”—which is to sweep the spirits of the just to God in the great Winnowing of Souls. . . .

Then into the indigo night vanishes forever from my eyes the ghost of Pelée; and the moon swings up,—a young and lazy moon, drowsing upon her back, as in a hammock. . . . Yet a few nights more, and we shall see this slim young moon erect,—gliding upright on her way,—coldly beautiful like a fair Northern girl.

AND ever through tepid nights and azure days the Guadeloupe rushes on,—her wake a river of snow beneath the sun, a torrent of fire beneath the stars,—steaming straight for the North.

Under the peaking of Montserrat we steam,—beautiful Montserrat, all softly wrinkled like a robe of greenest velvet fallen from the waist!—breaking the pretty sleep of Plymouth town behind its screen of palms . . . young palms, slender and full of grace as creole children are;—

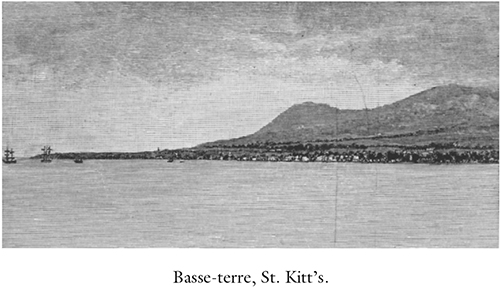

And by tall Nevis, with her trinity of dead craters purpling through ocean-haze;—by clouded St. Christopher’s mountain-giant;—past ghostly St. Martin’s, far-floating in fog of gold, like some dream of the Saint’s own Second Summer;—

Past low Antigua’s vast blue harbor,—shark-haunted, bounded about by huddling of little hills, blue and green;—

Past Santa Cruz, the “Island of the Holy Cross,”—all radiant with verdure though wellnigh woodless,—nakedly beautiful in the tropic light as a perfect statue;—

Past the long cerulean reaching and heaping of Porto Rico on the left, and past hopeless St. Thomas on the right,—old St. Thomas, watching the going and the coming of the commerce that long since abandoned her port,—watching the ships once humbly solicitous for patronage now turning away to the Spanish rival, like ingrates forsaking a ruined patrician;—

And the vapory Vision of St. John;—and the grey ghost of Tortola,—and further, fainter, still more weirdly dim, the aureate phantom of Virgin Gorda.

THEN only the enormous double-vision of sky and sea.

The sky: a cupola of blinding blue, shading down and paling into spectral green at the rim of the world,—and all fleckless, save at evening. Then, with sunset, comes a light gold-drift of little feathery cloudlets into the West,—stippling it as with a snow of fire.

The sea: no flower-tint may now make any comparison for the splendor of its lucent color. It has shifted its hue;—for we have entered into the Azure Stream: it has more than the magnificence of burning cyanogen. . . .

But, at night, the Cross of the South appears no more. And other changes come, as day succeeds to day,—a lengthening of the hours of light, a longer lingering of the after-glow,—a cooling of the wind. Each morning the air seems a little cooler, a little rarer;—each noon the sky looks a little paler, a little further away—always heightening, yet also more shadowy, as if its color, receding, were dimmed by distance,—were coming more faintly down from vaster altitudes.

. . . Mademoiselle is petted like a child by the lady passengers. And every man seems anxious to aid in making her voyage a pleasant one. For much of which, I think, she may thank her eyes!

A DIM morning and chill;—blank sky and sunless waters: the sombre heaven of the North with colorless horizon rounding in a blind grey sea. . . . What a sudden weight comes to the heart with the touch of the cold mist, with the spectral melancholy of the dawn!—and then what foolish though irrepressible yearning for the vanished azure left behind!

. . . The little monkeys twitter plaintively, trembling in the chilly air. The parrots have nothing to say: they look benumbed, and sit on their perches with eyes closed.

. . . A vagueness begins to shape itself along the verge of the sea, far to port: that long heavy clouding which indicates the approach of land. And from it now floats to us something ghostly and frigid which makes the light filmy and the sea shadowy as a flood of dreams,—the fog of the Jersey coast.

At once the engines slacken their respiration. The Guadeloupe begins to utter her steam-cry of warning,—regularly at intervals of two minutes,—for she is now in the track of all the ocean vessels. And from far away we can hear a heavy knelling,—the booming of some great fog-bell.

. . . All in a white twilight. The place of the horizon has vanished;—we seem ringed in by a wall of smoke. . . . Out of this vapory emptiness—very suddenly—an enormous steamer rushes, towering like a hill—passes so close that we can see faces, and disappears again, leaving the sea heaving and frothing behind her.

. . . As I lean over the rail to watch the swirling of the wake, I feel something pulling at my sleeve: a hand,—a tiny black hand,—the hand of a sakiwinki. One of the little monkeys, straining to the full length of his string, is making this dumb appeal for human sympathy;—the bird-black eyes of both are fixed upon me with the oddest look of pleading. Poor little tropical exiles! I stoop to caress them; but regret the impulse a moment later: they utter such beseeching cries when I find myself obliged to leave them again alone! . . .

. . . Hour after hour the Guadeloupe glides on through the white gloom,—cautiously, as if feeling her way; always sounding her whistle, ringing her bells, until at last some brown-winged bark comes flitting to us out of the mist, bearing a pilot. . . . How strange it must all seem to Mademoiselle who stands so silent there at the rail!—how weird this veiled world must appear to her, after the sapphire light of her own West Indian sky, and the great lazulite splendor of her own tropic sea!

But a wind comes!—it strengthens,—begins to blow very cold. The mists thin before its blowing; and the wan blank sky is all revealed again with livid horizon around the heaving of the iron-grey sea.

. . . Thou dim and lofty heaven of the North,—grey sky of Odin,—bitter thy winds and spectral all thy colors!—they that dwell beneath thee know not the glory of Eternal Summer’s green,—the azure splendor of southern day!—but thine are the lightnings of Thought illuminating for human eyes the interspaces between sun and sun. Thine the generations of might,—the strivers, the battlers,—the men who make Nature tame!—thine the domain of inspiration and achievement,—the larger heroisms, the vaster labors that endure, the higher knowledge, and all the witchcrafts of science! . . .

But in each one of us there lives a mysterious Something which is Self, yet also infinitely more than Self,—incomprehensibly multiple,—the complex total of sensations, impulses, timidities belonging to the unknown past. And the lips of the little stranger from the tropics have become all white, because that Something within her,—ghostly bequest from generations who loved the light and rest and wondrous color of a more radiant world,—now shrinks all back about her girl’s heart with fear of this pale grim North. . . . And lo!—opening mile-wide in dream-grey majesty before us,—reaching away, through measureless mazes of masting, into remotenesses all vapor-veiled,—the mighty perspective of New York harbor! . . .

Thou knowest it not, this gloom about us, little maiden;—’tis only a magical dusk we are entering,—only that mystic dimness in which miracles must be wrought! . . . See the marvellous shapes uprising,—the immensities, the astonishments! And other greater wonders thou wilt behold in a little while, when we shall have become lost to each other forever in the surging of the City’s million-hearted life! . . . ’Tis all shadow here, thou sayest?—Ay, ’tis twilight, verily, by contrast with that glory out of which thou camest, Lys—twilight only,—but the Twilight of the Gods! . . . Adié, chè!—Bon-Dié ké béni ou! . . .