GRAND ISLE, 1884

DEAR PAGE,—I wish you were here; for I am sure that the enjoyment would do you a great deal of good. I had not been in sea-water for fifteen years, and you can scarcely imagine how I rejoice in it,—in fact I don’t like to get out of it at all. I suppose you have not been at Grande Isle—or at least not been here for so long that you have forgotten what it looks like. It makes a curious impression on me: the old plantation cabins, standing in rows like village-streets, and neatly remodelled for more cultivated inhabitants, have a delightfully rural aspect under their shadowing trees; and there is a veritable country calm by day and night. Grande Isle has suggestions in it of several old country fishing villages I remember, but it is even still more charmingly provincial. The hotel proper, where the tables are laid,—formerly, I fancy, a sugar-house or something of that sort,—reminds one of nothing so much as one of those big English or Western barn-buildings prepared for a holiday festival or a wedding-party feast. The only distinctively American feature is the inevitable Southern gallery with white wooden pillars. An absolutely ancient purity of morals appears to prevail here:—no one thinks of bolts or locks or keys, everything is left open and nothing is ever touched. Nobody has ever been robbed on the island. There is no iniquity. It is like a resurrection of the days of good King Alfred, when, if a man were to drop his purse on the highway, he might return six months later to find it untouched. At least that is what I am told. Still I would not like to leave one thousand golden dinars on the beach or in the middle of the village. I am still a little suspicious—having been so long a dweller in wicked cities.

I was in hopes that I had made a very important discovery; viz.—a flock of really tame and innocuous cows; but the innocent appearance of the beasts is, I have just learned, a disguise for the most fearful ferocity. So far I have escaped unharmed; and Marion has offered to lend me his large stick, which will, I have no doubt, considerably aid me in preserving my life.

Could n’t you manage to let me stay down here until after the Exposition is over, doing no work and nevertheless drawing my salary regularly? . . . By the way, one could save money by a residence at Grande Isle. There are no temptations—except the perpetual and delicious temptation of the sea.

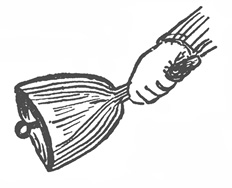

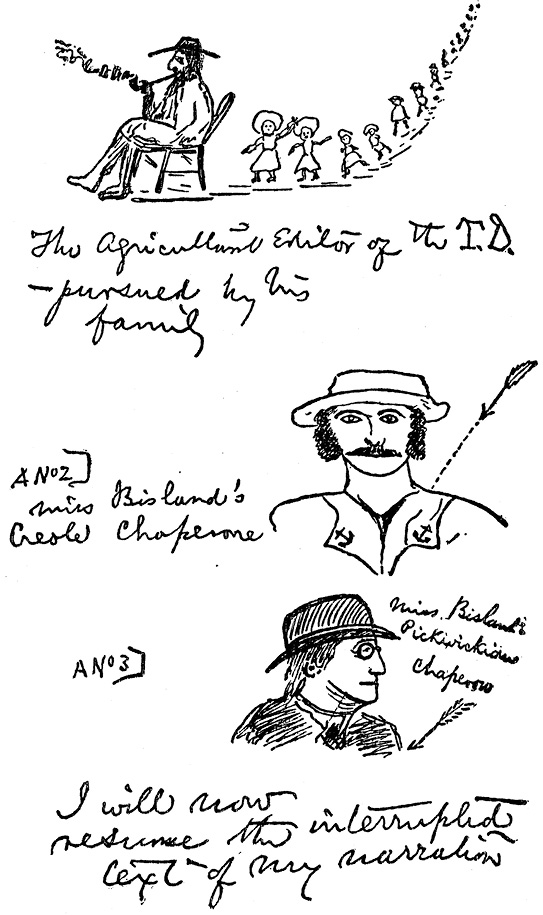

The insects here are many; but I have seen no frogs,—they have probably found that the sea can outroar them and have gone away jealous. But in Marion’s room there is a beam, and against that beam there is the nest of a “mud-dauber.” Did you ever see a mud-dauber? It is something like this when flying;—but when it is n’t flying I can’t tell you what it looks like, and it has the peculiar power of flying without noise. I think it is of the wasp-kind, and plasters its mud nest in all sorts of places. It is afraid of nothing—likes to look at itself in the glass, and leaves its young in our charge. There is another sociable creature—hope it is n’t a wasp—which has built two nests under the edge of this table on which I write to you. There are no specimens here of the cimex lectularius; and the mosquitoes are not at all annoying. They buzz a little, but seldom give evidence of hunger. Creatures also abound which have the capacity of making noises of the most singular sort. Up in the tree on my right there is a thing which keeps saying all day long, quite plainly, “Kiss, Kiss, Kiss!”—referring perhaps to the good young married folks across the way; and on the road to the bath-house, which we travelled late last evening in order to gaze at the phosphorescent sea, there dwells something which exactly imitates the pleasant sound of ice jingling in a cut-glass tumbler.

As for the grub, it is superb—solid, nutritious, and without stint. When I first tasted the butter I was enthusiastic, imagining that those mild-eyed cows had been instrumental in its production; but I have since discovered they were not—and the fact astonishes me not at all now that I have learned more concerning the character of those cows.

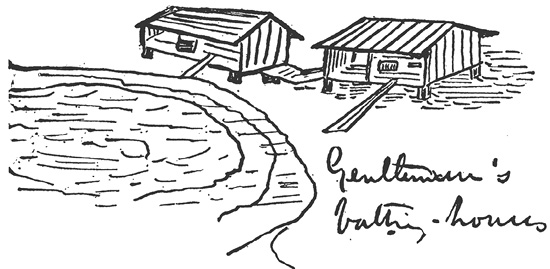

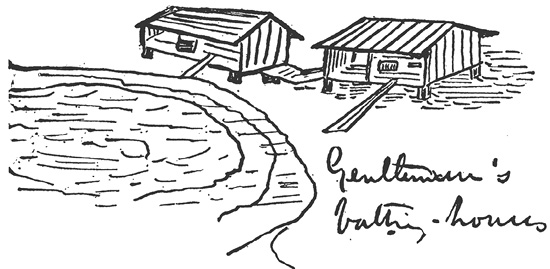

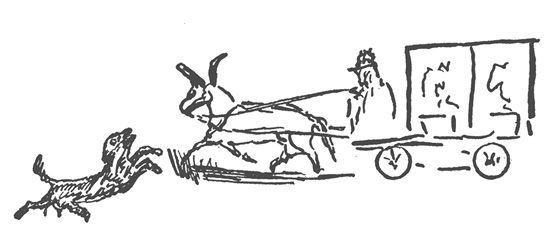

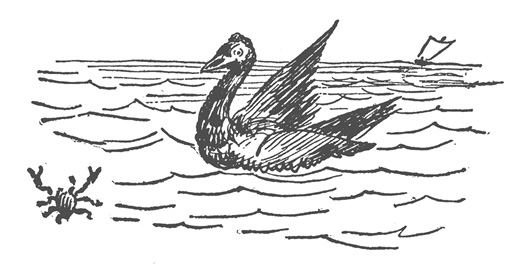

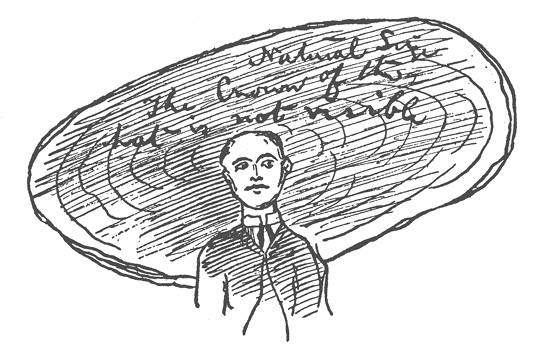

At some unearthly hour in the morning the camp-meeting quiet of the place is broken by the tolling of a bell. This means “Jump up, lazy-bones; and take a swim before the sun rises.” Then the railroad-car comes for the bathers, passing up the whole line of white cottages. The distance is short to the beach; Marion and I prefer to walk; but the car is a great convenience for the women and children and invalids. It is drawn by a single mule, and always accompanied by a dog which appears to be the intimate friend of the said mule, and who jumps up and barks all the grass-grown way. The ladies’ bathing-house is about five minutes’ plank-walking from the men’s,—where I am glad to say drawers and bathing-suits are unnecessary, so that one has the full benefit of sun-bathing as well as salt-water bathing. There is a man here called Margot or Margeaux—perhaps some distant relative of Château-Margeaux—who always goes bathing accompanied by a pet goose. The goose follows him just like a dog; but is a little afraid of getting into deep water. It remains in the surf presenting its stern-end to the breakers:—

The only trouble about the bathing is the ferocious sun. Few people bathe in the heat of the day, but yesterday we went in four times; and the sun nearly flayed us. This morning we held a council of war and decided upon greater moderation. There are three bars, between which the water is deep. The third bar is, I fear, too “risky” to reach, as it is nearly a mile from the other, and lies beyond a hundred-foot depth of water in which sharks are said to disport themselves. I am almost as afraid of sharks as I am of cows. . . . Marion made a dash for a drowning man yesterday, in answer to the cry, “Here, you fellows, help! help!” and I followed. We had instantaneous visions of a gold-medal from the Life-Saving Service, and glorious dreams of newspaper fame under the title “Journalistic Heroism,”—for my part, I must acknowledge I had also an unpleasant fancy that the drowning man might twine himself about me, and pull me to the bottom,—so I looked out carefully to see which way he was heading. But the beatific Gold-Medal fancies were brutally dissipated by the drowning man’s success in saving himself before we could reach him, and we remain as obscure as before.

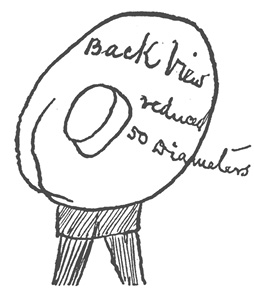

The proprietor has found what I have vainly been ransacking the world for—a civilized hat, showing the highest evolutional development of the hat as a practically useful article. I am going to make him an offer for it.

Alas! the time flies too fast. Soon all this will be a dream:—the white cottages shadowed with leafy green,—the languid rocking-chairs upon the old-fashioned gallery,—the cows that look into one’s window with the rising sun,—the dog and the mule trotting down the flower-edged road,—the goose of the ancient Margot,—the muttering surf upon the bar beyond which the sharks are,—the bath-bell and the bathing belles,—the air that makes one feel like a boy,—the pleasure of sleeping with doors and windows open to the sea and its everlasting song,—the exhilaration of rising with the rim of the sun. . . . And then we must return to the dust and the roar of New Orleans, to hear the rumble of wagons instead of the rumble of breakers, and to smell the smell of ancient gutters instead of the sharp sweet scent of pure sea wind. I believe I would rather be old Margot’s goose if I could. Blessed goose! thou knowest nothing about the literary side of the New Orleans Times-Democrat; but thou dost know that thou canst have a good tumble in the sea every day. If I could live down here I should certainly live to be a hundred years old. One lives here. In New Orleans one only exists. . . . And the boat comes—I must post this incongruous epistle.

Good-bye,—wish you were here, sincerely.

Very truly,

LAFCADIO HEARN.