One

MOUNTAINS, SAND, WIND,

AND WATER FORM DUNES

Gazing upon the huge piles of sand stacked up against the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, the obvious question for every visitor is: “Where did they come from?” After all, this is a mountain valley, not a desert or a seashore where one might expect dunes. To the west of the San Luis Valley, the San Juan Mountains are of volcanic origin. Erosion of those rocks creates sand particles, which are carried east by water to the San Luis Valley and are then blown by the prevailing southwesterly winds to pile up against the blockading Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Another source of sand is the erosive action of swift mountain streams, such as Sand Creek and Medano Creek, which bring sand westward from the Sangre de Cristos. Primarily quartzite in origin, this sand is deposited at the base of the dunes and blown back onto them by the southwesterly winds.

Thus, wind and water are the key elements in the formation of the dunes with the mountain ranges on the west and east providing source rock for the sand particles. Furthermore, the mountains on the east, the Sangre de Cristos, block the sand from being blown any farther east, and the dunes are formed where the southwesterly wind is funneled through three mountain passes: Music Pass, Medano Pass, and Mosca Pass (from north to south). Sometimes, there are northeasterly winds, which tend to blow the dunes back upon themselves, preventing further encroachment eastward.

Geologists estimate the dunes to be about 12,000 years old. They are part of a four-fold ecological system shown in the diagram on the following page—the watershed (the streams of the Sangre de Cristos, which bring sand westward), the dunefield (the highest dunes, reaching over 700 feet high), the sand sheet (an area of sand not fully gathered into dunes, held fairly stable by vegetation), and the sabkha (an area of shallow lakes that are formed from the fluctuating water table and which, when dried up, leave behind an alkaline, crusty soil). Geologists are constantly studying these ecosystems and how the various parts interact with each other.

ECOLOGICAL SYSTEM VIEWED EAST TO SANGRE DE CRISTO MOUNTAINS. Geologists are still studying how the four parts of the system affect each other. For example, if snowfall is meager in the mountain watershed one winter, how does that affect stream flow and the amount of sand deposition? If groundwater is excessively pumped out of the basin for crop irrigation or pumped east to Front Range cities, how does that affect the stability of the dunefield? If vegetation is lost from the sand sheet, will that mean more sand deposition and higher dunes on the dunefield? If the sabkha lakes are dried up by drought or excessive groundwater pumping, how will that affect the sand sheet and the dunefield? This is a very complex system, and scientists will continue to find answers to these and other questions as further studies are conducted. The purpose of the creation of Great Sand Dunes National Park & Preserve was to protect this entire ecosystem. (GRSA.)

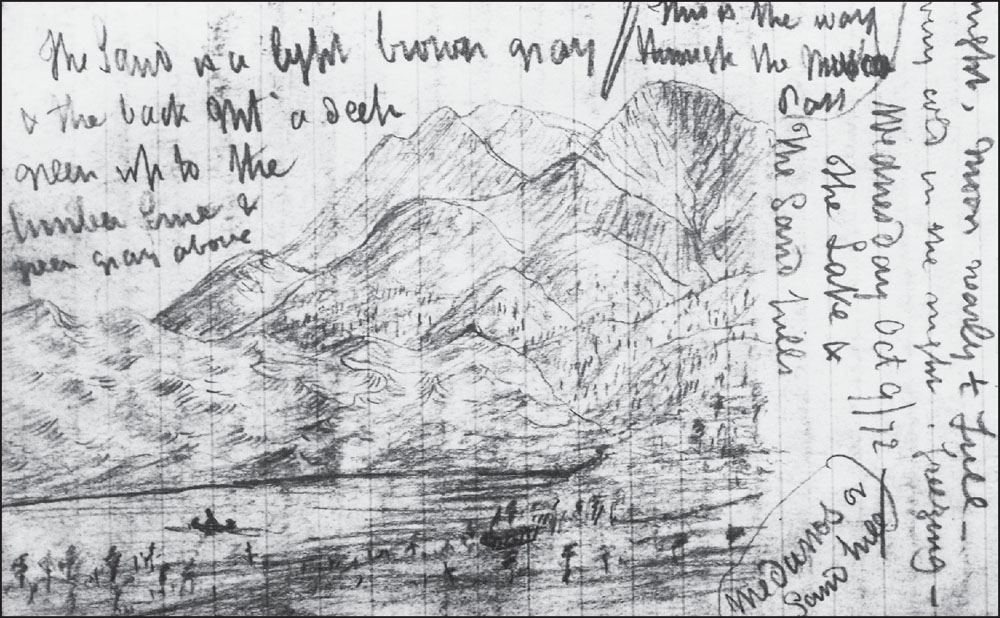

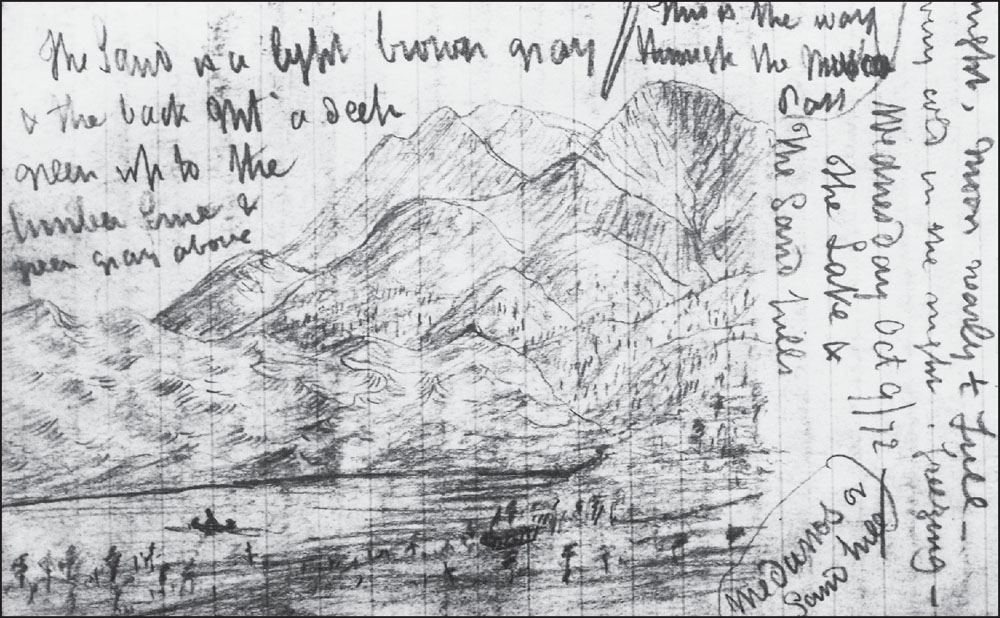

“THE LAKE AND THE SAND HILLS.” This sketch, done by Samuel Richardson on Wednesday, October 9, 1872, is one of the first recorded drawings of the Great Sand Dunes. The dunes appear left of center, below the peaks, with water (noted as “the lake”) below the dunes. At the top is written, “This is the way through the Mosca Pass.” (GRSA.)

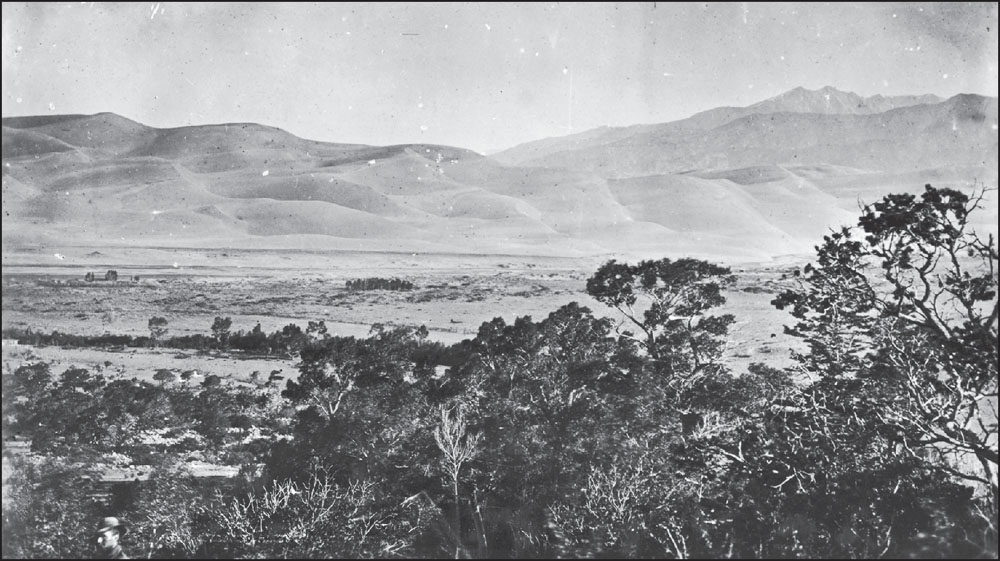

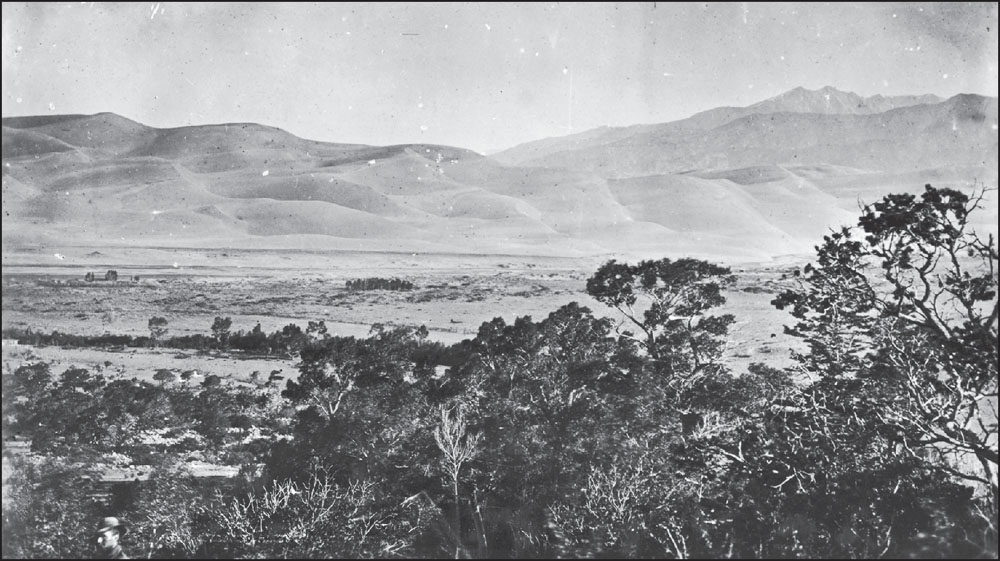

GREAT SAND DUNES, 1874. This image by frontier photographer William Henry Jackson is the first known photograph of the dunes. Medano Creek appears to be dry at the base of the dunes, indicating a late-summer or fall time frame. The twin-peak mountain at the upper right is Cleveland Peak with an elevation of 13,414 feet. (GRSA.)

ENLARGEMENT OF WILLIAM HENRY JACKSON’S 1874 PHOTOGRAPH. An amazing similarity in the general shape of the Great Sand Dunes is shown in these two photographs, taken 137 years apart. The same three hills are shown in each photograph with Cleveland Peak to the right. (GRSA.) 15

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE PHOTOGRAPH, 2011. The similarity of the three hills reflects the overall stability of the dunefield over a long period of time. Opposing wind directions (southwest/northeast) along the mountain front are the main reason for the dunes stability. Lower down their slope, the dunes show more diversity in wave patterns. (GRSA.)

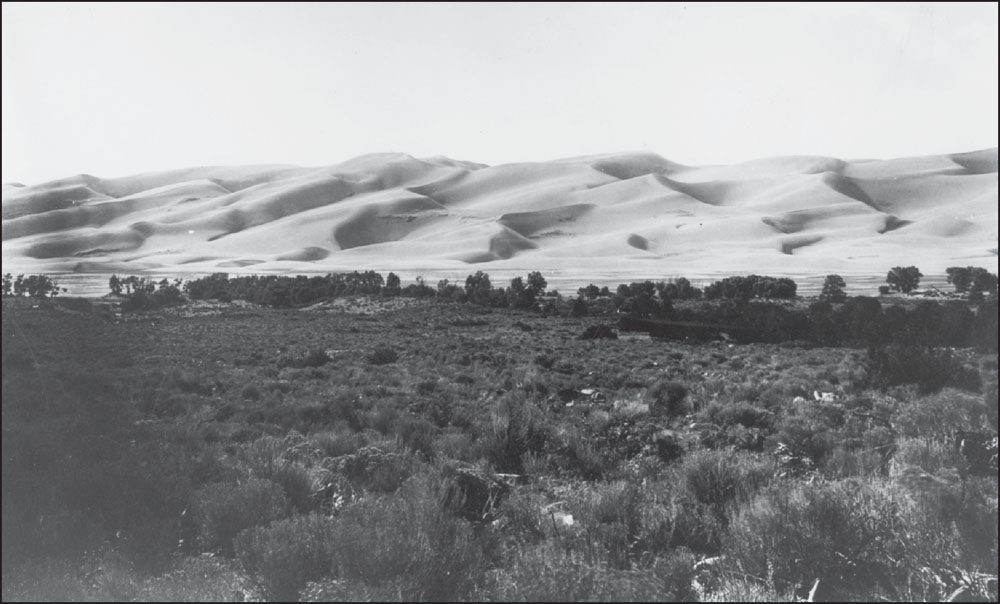

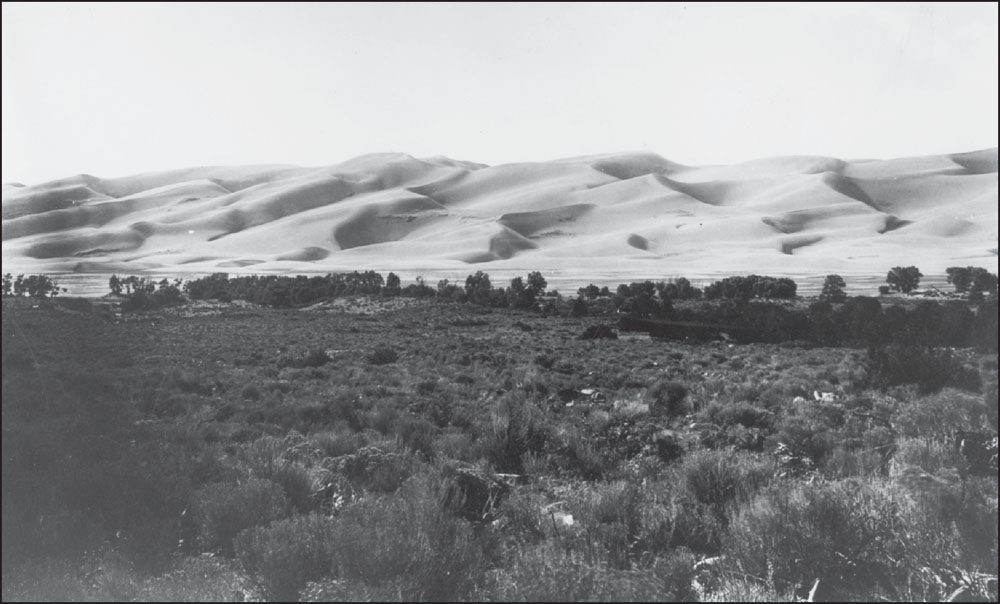

“SAND HILLS WEST END, 1919.” Photographer Ory T. (O.T.) Davis took some of the first known photographs of the Great Sand Dunes after William Henry Jackson. Davis, from Iowa, originally tried copper mining on Pass Creek, east of the Sangre de Cristos. When the mines played out, he moved to Walsenburg and started a commercial photography business. (MVHS.)

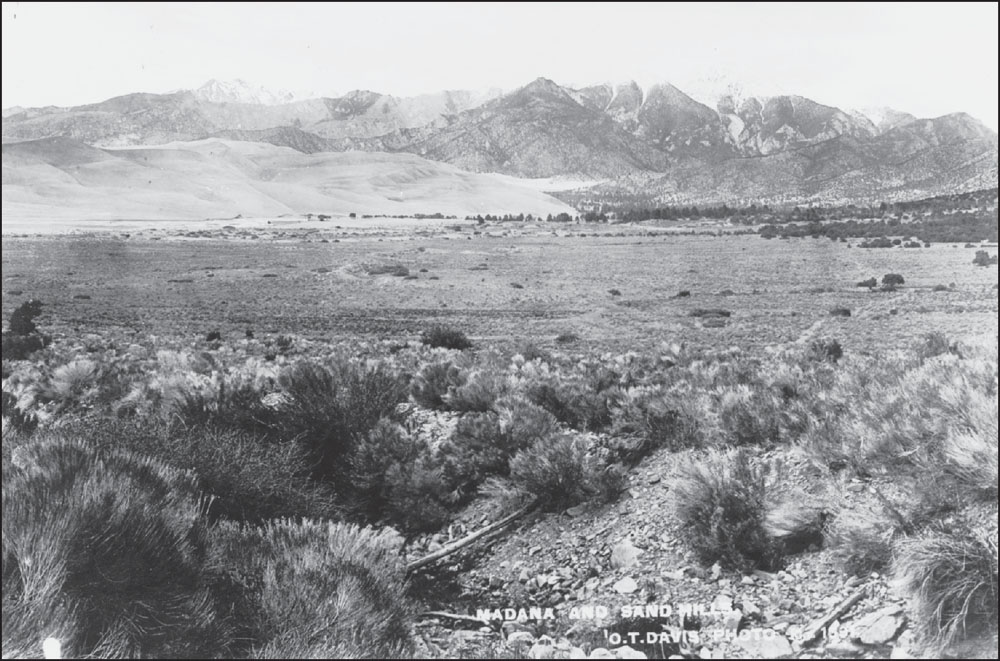

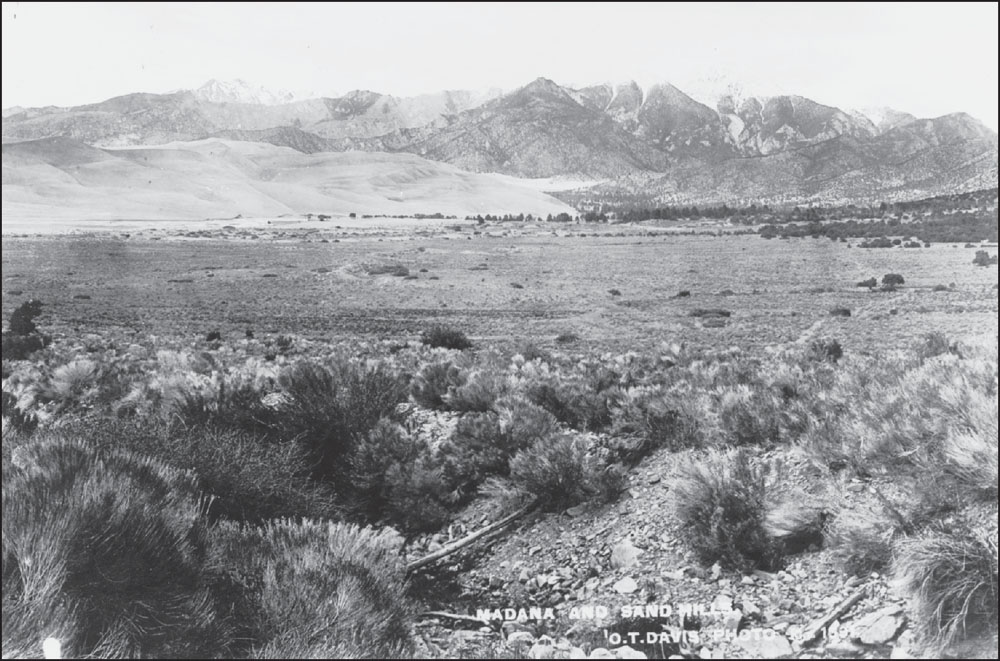

“MADANA AND SAND HILL, 1919.” This O.T. Davis photograph captures the view farther east from the one above. Davis labeled Medano Creek “Madana” based upon local pronunciation. He had, by this time, moved his photography business west from the Walsenburg/La Veta area to Alamosa, which is the nearest large town to the Great Sand Dunes. (MVHS.)

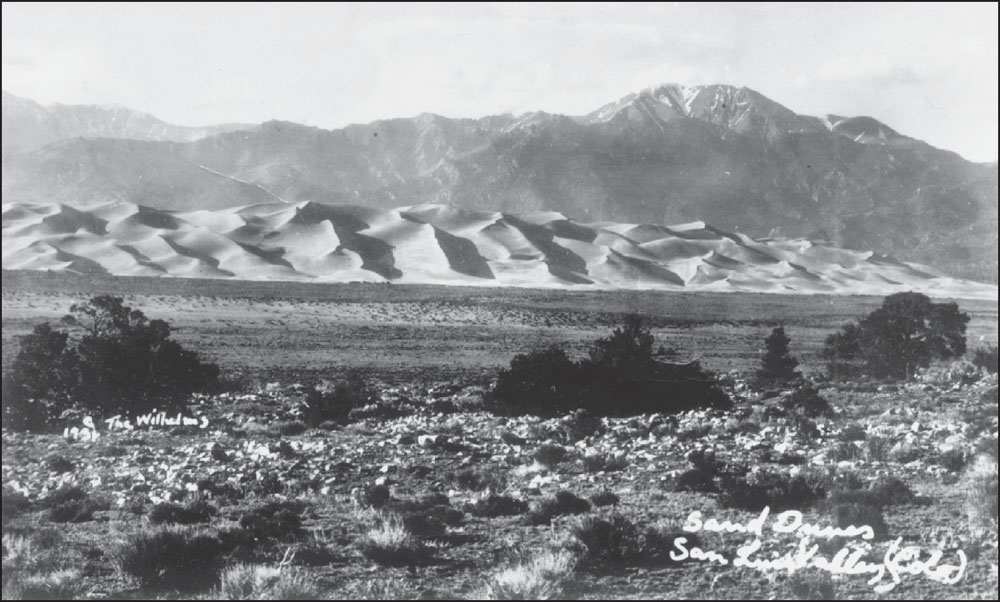

ROAD TO GREAT SAND DUNES, 1927. The primitive, two-track road seen in the mid-foreground of this Wilhelm family photograph shows how difficult it was to drive a vehicle to the dunes in 1927. This northward view shows the jagged Crestone Peaks to the left, Cleveland Peak in the center, and Mount Herard to the right, all rising high above the dunes. (GRSA-5594.)

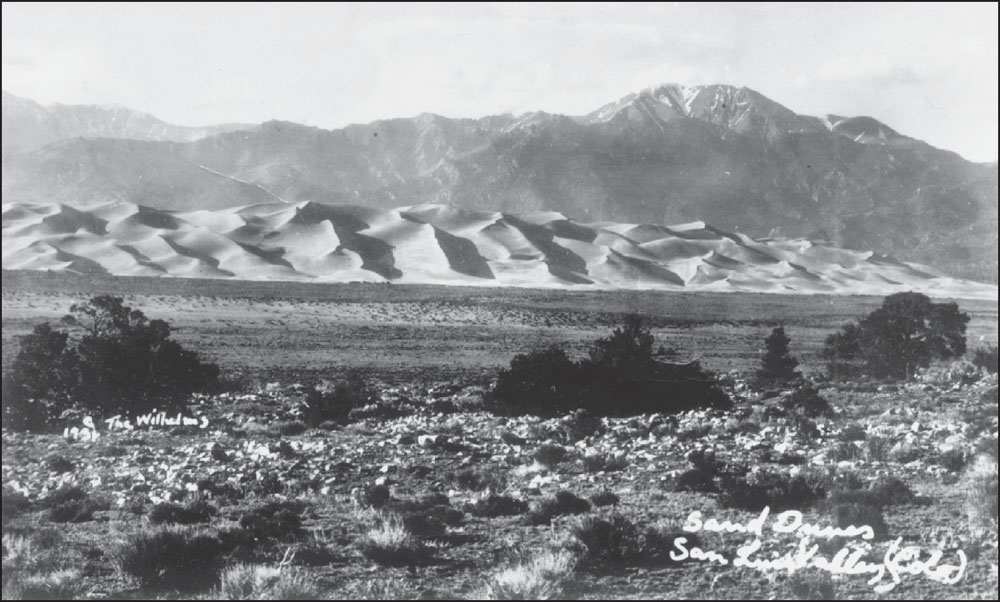

MOUNT SEVEN AND THE DUNES, 1931. This Wilhelm photograph shows the Great Sand Dunes one year before they became a national monument in 1932. Mount Seven towers above the dunes at an elevation of 13,297 feet. In 1984, it was renamed Mount Herard in honor of the pioneering Herard family of Medano Canyon. (GRSA-747.)

WINDMILL AT THE OUTPOST, 1974. Wind and water are the two main factors contributing to the formation of the Great Sand Dunes. Southwesterly winds blow sand across the San Luis Valley to the dunefield. This windmill used wind power to pump water up to the outpost, located just south of today’s Sand Dunes Oasis campground and store. (GRSA.)

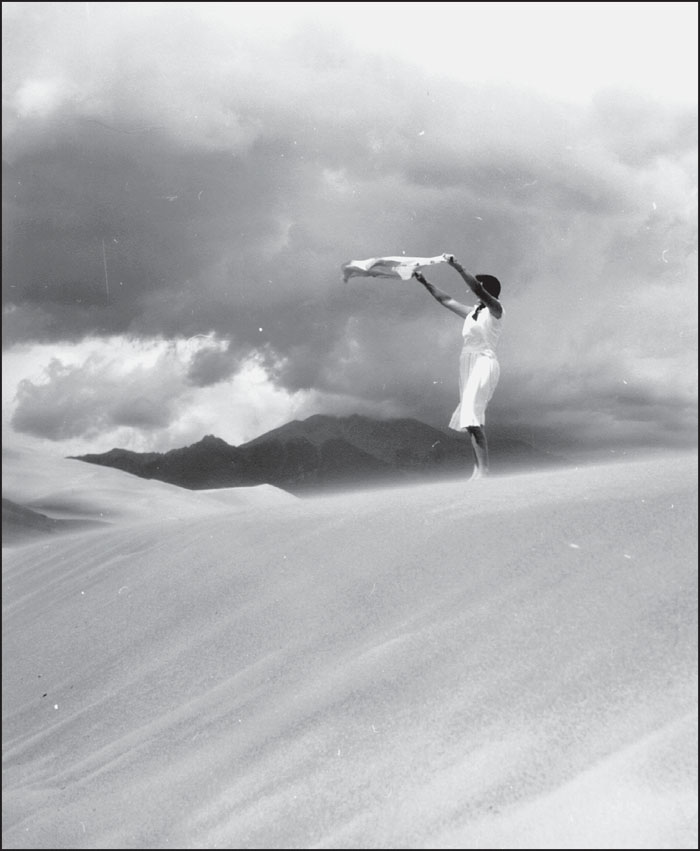

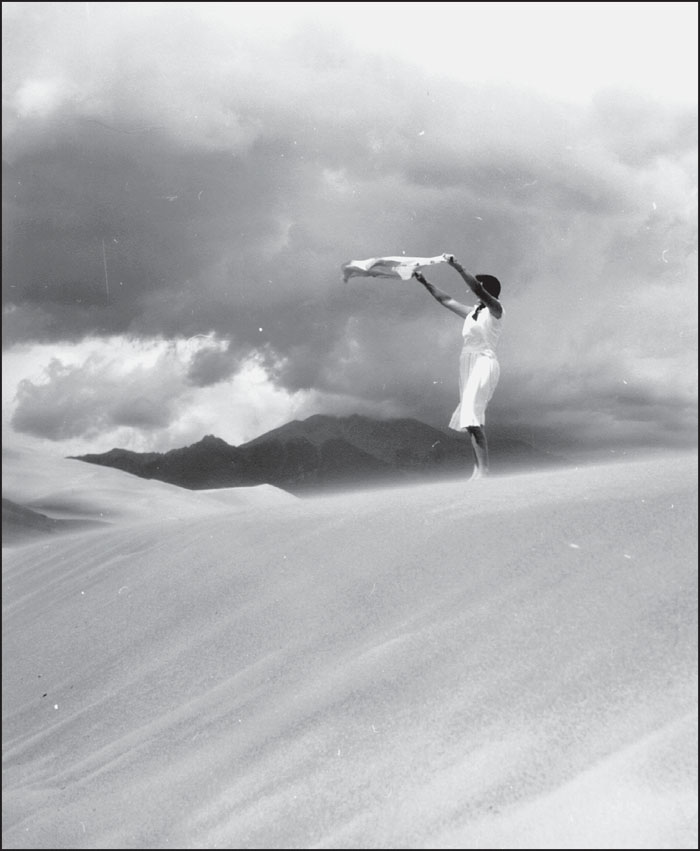

WIND ON THE DUNES, 1961. Robert Haugen took this dramatic photograph of the wind blowing a woman’s scarf on the dunes. Blowing sand is visible at her feet. While dune ridges are shifting all the time, the dunefield itself is stabilized by opposing primary wind directions. (GRSA-5602.)

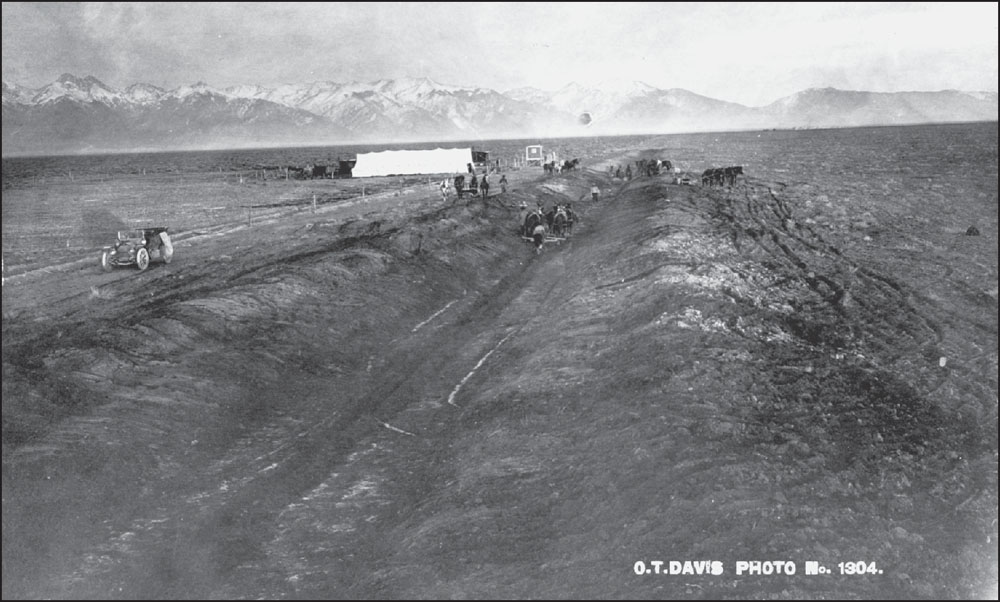

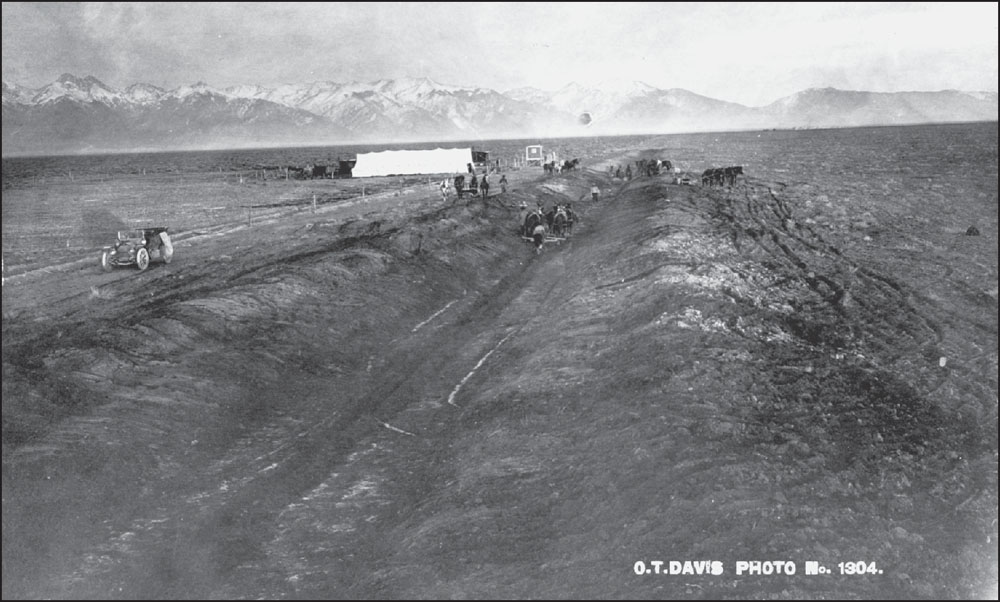

STEAM POWERED IRRIGATION DITCH DIGGER, 1912. O.T. Davis shot this photograph on the plains east of Hooper. Water (both groundwater and flowing streams) is another major factor in the formation of the Great Sand Dunes. Water is also essential to irrigation of farms in the San Luis Valley. Here, this ditch digger is hard at work as members of the Alamosa Boosters Club look on. (MVHS.)

IRRIGATION DITCH NEAR HOOPER, 1911. This O.T. Davis view looks east toward the Sangre de Cristo Mountains with the Great Sand Dunes visible as a light blur at the base of the mountains. Irrigated crops in the San Luis Valley include potatoes, sugar beets, and beans. (MVHS.)

IRRIGATION DITCH EAST OF MOSCA, C. 1912. This completed irrigation ditch in O.T. Davis’s photograph illustrates the dependence of crops in the dry San Luis Valley upon groundwater pumped to the canals. The view looks east toward the Blanca massif of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. (MVHS.)

IRRIGATION DITCH EAST OF MOSCA, 2012. A century later, the huge ditches still carry water across the San Luis Valley. This view is just south of San Luis Lake State Park, looking west toward the Great Sand Dunes and Mosca Pass (seen as the low point on the mountain ridge). Excessive groundwater pumping is now seen as a threat to the dunes.

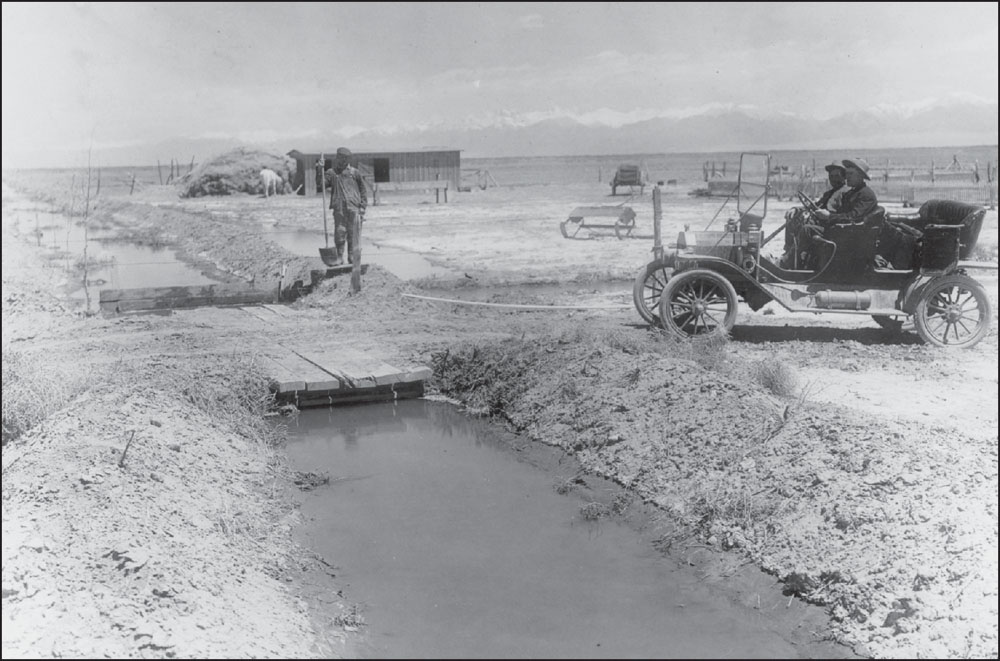

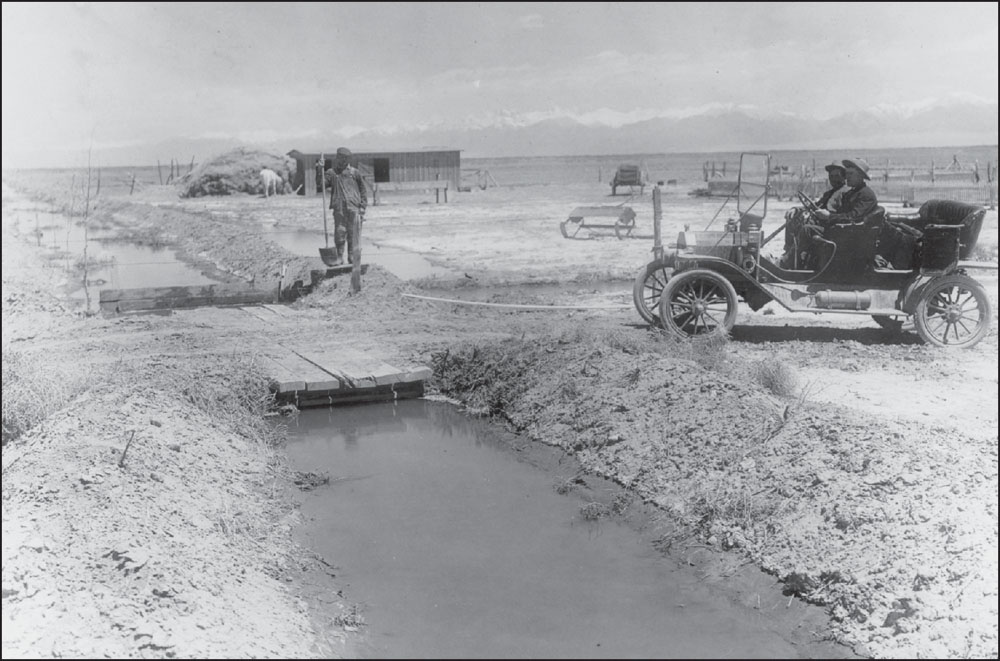

WILLIAM GEORGE RANCH NEAR ALAMOSA, 1912. Photographer O.T. Davis was on hand to capture this scene of an automobile about to cross a bridge over an irrigation ditch in the San Luis Valley. The Sangre de Cristo Mountains can be seen in the background. (MVHS.)

“PRARIE DITCH” NEAR MOSCA, 1912. Automobile passengers cooled their heels at the irrigation ditch as O.T. Davis took their photograph. Mosca is the nearest town to the Great Sand Dunes and is the official mailing address for the national park. (MVHS.)

WATER REFLECTION, C. 1962. Water is the lifeblood of the Great Sand Dunes and the San Luis Valley. Mount Herard and the dunes are captured here in the reflection of this temporary pool of water.

MEDANO CREEK BED, OCTOBER 1951. When Medano Creek dries up, it is easy to see the massive quantities of sand it has brought down from the Sangre de Cristos. This sand is then blown back onto the dune piles by the prevailing southwesterly winds. Mountains, sand, wind, and water are the natural elements in dune creation. (GRSA-2300.)