INTRODUCTION

At some point in the life of every sports fan there comes a moment of reckoning. It may happen when your team wins on a last-second field goal or three-point basket and you suddenly find yourself clenched in a loving embrace with a large hairy man you’ve never met and with whom you have nothing in common except allegiance to the same team. Or it may come in the long, hormonally depleted days after a loss, when you’re felled by a sensation oddly similar to the one you felt when you first experienced the death of a pet. In such moments, even the fan who rigorously avoids anything approaching self-awareness is sometimes forced to confront a version of the question others—spouses, friends, children, and colleagues—have asked for years: “Why do I care?” In very general terms that’s what this book is about—the human obsession with contests.

I grew up in Alabama—possibly the worst place on earth to acquire a healthy perspective on the importance of spectator sports. If you were a scientist hoping to isolate the fan gene, Alabama would make the perfect laboratory. People in Alabama have a general interest in almost all sports—the state is second only to Nevada in the amount of money that its citizens bet on sports, despite the fact that in Alabama, unlike Nevada, sports gambling is illegal. But the sport that inspires true fervor—the one that compels people there to name their children after a popular coach and to heave bricks through the windows of an unpopular one—is college football. A recent poll by the Mobile Register found that 90 percent of the state’s citizens describe themselves as college football fans. Eighty-six percent of them pull for one of the two major football powers there, Alabama or Auburn, and 4 percent pull for other teams—Florida, Notre Dame, Georgia, Tennessee, and Michigan, or smaller schools like Alabama A&M or Alabama State. To understand what an absolute minority nonfans are in Alabama, consider this: they are outnumbered there by atheists.

My team is the Alabama Crimson Tide. Growing up a Tide fan in the 1970s gave me an unrealistic sense of what it means to be a fan, for the simple reason that in the 1970s Alabama won, and being a sports fan is largely about learning to cope with losing. In most sports there is just one champion per year—every four years if you’re into a sport like World Cup soccer—so for the overwhelming majority of fans, losing at least once a season is a near certainty. In my childhood, this small kink in the works of the fan’s life went more or less unexposed.

The primary agent of this obfuscation was a man named Paul “Bear” Bryant, the gravelly voiced football coach with an old-growth frame who coached Alabama to six national championships and who, when I was eleven, set the record for the most wins of any college football coach in history. Along the way, the Bear, as he was called for taking up a childhood dare to wrestle a bear at a local fair, became a populist hero who hovered over the consciousness not just of every little kid in the state but of nearly every adult as well; his photograph, usually in his houndstooth fedora, hung on the wall of every barbecue and burger joint from Mobile to Muscle Shoals. His exalted status was proclaimed on thousands of bumper stickers, T-shirts, and homemade shrines. Socially and historically, the Bear was a complicated figure; he waited until 1970 to integrate the Alabama football team, and on matters of race Bryant was more or less silent. Given his stature in Alabama at the time of the civil rights struggle, that silence could only be interpreted as a tacit, if not wholehearted, endorsement of the status quo. But to a kid who didn’t yet understand the connection of sports to culture and politics, these were incomprehensible complexities at the time. To me back then, the Bear was just a football coach.

Early in the morning of October 17, 1982, a Sunday and my thirteenth birthday, my father woke me and told me to put on a sweater and some khakis, to tuck my shirt in, and to get a move on. He had a friend who owned a local lawnmower dealership that sponsored The Bear Bryant Show, the Sunday morning postgame recap that enthralled Tide fans the way televised papal sermons seize the attention of devout Catholics, and the friend had managed to get me invited on the set. I didn’t know this at the time, but I had an inkling where we might be headed—besides church, little else of importance happened early on Sunday mornings in Birmingham, and I was fairly sure that my birthday present wasn’t going to consist of a morning of hymn singing at Independent Presbyterian. But the other possibility—that I was going to stand face to face with the most revered man in the state of Alabama and the architect of more joyful Saturdays in my young life than I could count—was too terrifying to contemplate. I had an exaggerated view of the man; once in grade school I looked at a picture of Mt. Rushmore and noted what a poor job the sculptor had done of capturing the Bear’s likeness, and that he’d forgotten the hat.

We rode in silence through the empty streets, past the Tudor and clapboard houses with lawns like swatches of green felt, past the red clay outcroppings near Birmingham’s iron ore seam, and up the winding road to the television studios, where Bryant taped his show for broadcast that afternoon. The parking lot, which overlooked downtown Birmingham, was empty save a few cars and some smashed soda cans. As soon as I got out of the car, I spotted Bryant’s bodyguard, a black university policeman named Billy Varner, who was sitting at the door in front of the studio, a wide-brimmed trooper’s hat low over his eyes. I’d seen him standing on the sideline of every Alabama game I’d been to, and in almost every television shot or photograph I’d ever seen of Bryant. The Bear couldn’t be more than a few feet away.

“How’s the Coach?” my father asked as we walked by, using the man’s proper title, as all Tide fans knew to do.

“Not too good,” Varner replied.

The day before, Alabama had lost to Tennessee, something that hadn’t happened since my first birthday, in 1970. Varner had the Sunday morning Birmingham News at his feet; the outcome of the game was front-page news. Bryant was sixty-nine, and even as a kid, I sensed something ominous about the loss. It broached the unspeakable possibility that perhaps the old coach was losing his stuff. I walked through two sets of large steel doors, and there he was: a glowering hulk of a man with a voice so deep it seemed to vibrate the floor. He was sitting behind a desk like a news anchor, on a sky blue soundstage hung with signs advertising Coca-Cola and Golden Flake potato chips. His gray hair was slicked back, his cheeks were still red from the game-day sun. But his face was fixed in a steely grimace, and his eyes were bloodshot and wet, as though he hadn’t slept. The Bear looked like he was grieving. I felt a pang of resignation: my one chance to meet the Bear and his mood was positively black.

I sat on a stool behind the cameraman as Bryant mumbled gravely through the show and took the blame for each fumble, each missed tackle, and each dropped ball. This was the Bear’s way, and it bothered me tremendously. I knew exactly who had fumbled, and it hadn’t been Bear Bryant. The captain was trying to go down with the ship, but at least one passenger wouldn’t let him.

After the taping, Bryant got up slowly from his chair and stood on the set looking dour and preoccupied. He turned around and noticed me, then approached and stuck out his hand in a distracted, obligatory way. We shook, and his pillowy palm seemed to engulf my arm.

“I wanna play football,” was all I could think to say.

“I’m sure you’ll do fine at it, son,” he said, and that was all. This wasn’t going to be the day to get motivational platitudes from the Bear. I wasn’t even disappointed; at the age of thirteen I knew enough about football and human emotions to feel badly for the old man. Losing to Tennessee, I figured, was hell on all of us.

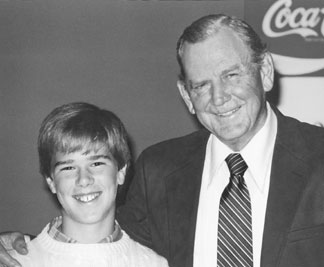

My father asked Bryant if he wouldn’t mind posing with me for a picture. Without so much as a word, the Bear put his arm around my shoulder and forced an unconvincing smile. We stood there in front of the Coca-Cola sign in this uncomfortable pose as my father fiddled with his camera, stalling in the hope that Bryant might loosen up. After forty-five nerve-fraying seconds, the Bear leaned over to me and thundered, “Son, I don’t think your father knows what the hell he’s doing.” We both laughed and in the photo that now hangs on my office wall we look like old cronies sharing an inside joke.

Two months later, Bryant retired, and fulfilling his prophecy that he’d die without football, he succumbed to a heart attack a month later. I skipped school the day of his funeral and made my mother drive me to Elmwood Cemetery for the burial. Thousands of Alabamians lined the forty-five-mile stretch of interstate between the university campus in Tuscaloosa and the cemetery in Birmingham. Bryant’s hearse and the three-mile procession of cars and buses behind took farewell laps around Bryant-Denny Stadium on campus in Tuscaloosa and Legion Field in Birmingham before heading to the cemetery, where I stood with ten thousand other mourners. Each Alabama win had served as a kind of temporal hash mark on the green turf of my youth, and after Bryant died I felt that field had turned brown.

It took getting away from Alabama to develop a little perspective on being a fan, and perspective came quickly when I arrived at Columbia University in New York in 1987, coincidentally during what would become, by my sophomore year, the longest losing streak in the history of college football. The Lions lost an astonishing forty-four games in a row, beating Northwestern’s previous record by ten games; an entire class of players graduated without achieving so much as a tie. It was quite an adjustment to go from counting up a record number of wins under the Bear to the inexorable accumulation of a record number of losses at Columbia. And just as disconcerting: no one at Columbia seemed to mind. Columbia was a kind of inverse Alabama; where 90 percent of Alabamians had a favorite team, a similar percentage at Columbia seemed not to know the rules. In Alabama, life more or less came to a halt on football Saturdays; in New York, almost no one went to Columbia games except for their comedic value, or else to witness some sort of losing milestone. Throngs of Columbia students crammed onto a New Jersey Transit local for the 1987 Princeton-Columbia game, just to see what they hoped would be the loss that propelled Columbia past Northwestern’s miserable streak. The Columbia fans, if you can call them that, wore Princeton orange and black and cheered wildly when Princeton scored. Some students unfurled a huge banner that read GO COLUMBIA—BEAT NORTHWESTERN! When Princeton won—as we knew they would—the Columbia students toasted the loss with champagne, celebrating the fact that we were, indisputably, the worst team ever. I can trace my first feelings of self-consciousness about being a sports fan to that cool October Saturday in New Jersey, because here’s the thing: I wanted Columbia to win. Try as I might, I couldn’t hope to lose. I couldn’t mock football. I was not a sports dadaist.

There were other revelations, and usually they came care of some form of public ridicule. I was ribbed for hanging the photograph of the Bear and me on my dorm-room wall. Actually, at first, I wasn’t ribbed at all; no one knew who the old man was—they assumed he was my grandfather. When his identity was discovered, the ridicule began. I don’t remember what was more unsettling, taking endless flak for having a picture of a football coach on my wall or the realization that there were people roaming the world who at close range could not recognize Bear Bryant.

Once I spent three hours listening to an Alabama-Auburn game on the telephone; there was no broadcast of the game in New York, so I called my parents in Alabama and had them lay the receiver next to a radio. When my friends realized what I was doing with a telephone next to my ear for three hours—well, suffice it to say there was more ridicule. And when an undefeated Alabama team lost to Auburn my junior year, I anesthetized myself with a steady drip of keg Budweiser. The next morning I woke up on my dorm-room bed, fully clothed and in the fetal position. My roommates reported that I’d taken refuge there at some point in the fourth quarter and had wept myself to sleep. I wasn’t in any shape to dispute this version of events, but again, was it so strange?

At some point, I began to get the clear impression that it was strange. The problem wasn’t that others thought my behavior was pathological, it was that I myself began to think something was a little . . . off. I’d gone to Columbia to study humanism and the great books—to become a rational being. Crying one’s self to sleep over the failure of a group of people you’ve never met to defeat another group of people against whom you have no legitimate quarrel—in a game you don’t play, no less—is not rational. It didn’t make me feel any better about myself that while I was obsessed over college football, others were obsessed with pro football, baseball, basketball, and soccer. At the time, I failed to grasp how much we had in common.

One of the most comforting experiences for anyone who considers himself weird in some way is to find other people in the world who are, in the same way, weirder. For me, this experience took place, plainly enough, care of the local TV news in Birmingham. Just about the time I was beginning to wonder if I should enroll in some sort of twelve-step sports fan recovery program, I went home from college to visit my family for Thanksgiving—no coincidence, the very week of that year’s Alabama-Auburn game. A few days before kickoff, I was flipping through the channels when I landed on a live broadcast from the parking lot of Legion Field, where the big game was to be played. As part of the week-long coverage that typically precedes that game, a local station was doing a lifestyle piece on people who drive motor homes to Alabama football games. That’s when I saw a scene that would define fan devotion for me for years to come.

A little background: In the early 70s, some mad football fan someplace—a lot of people contend that place was Birmingham—got it in his head to drive a motor home right up to the stadium on game day, probably for the simple reason that motor homes have bathrooms and therefore provided this fan and his beer-drinking buddies the luxury of a place to take a leak during their pregame tailgate party. Whatever the original motivation, the idea caught on; other people got it in their heads to drive their motorized bathrooms right up to the stadium on game day. The more people who did this, the harder it became to get a good parking place, so a few enterprising fans decided to show up not on game day, but a day or two before game day. After all, in addition to bathrooms, motor homes have beds, and kitchens and televisions—in fact, everything you need to squat someplace until the authorities run you off. More and more people came earlier and earlier, forming, over time, a large diesel-powered movable feast, the main course of which was a Saturday football game.

RVs completely changed the fan experience. Before, football games were circumscribed events. They took place inside a stadium on Saturdays and lasted about three hours, after which everyone went home. Logistical problems like traffic, the need for tickets, the need for those bathrooms—set games off from the rest of life. RVs blew open the experience. The event was no longer confined to three hours—it could last three days. In the South, the Midwest, and other pockets of fan mania throughout America, it’s not unheard of these days for fans to arrive in their motor homes a full week before kickoff—to drive directly from one game to the next. Futhermore, games no longer took place simply in a stadium, but in the neighborhoods around the stadium and on the open highways that brought fans together. The people who sought out the scene were necessarily among the most devoted. While there are plenty of obsessive football fans out there who’ve never set foot in an RV, for those whose passion for football was unchecked, the RV offered the possibility of total immersion.

Of all these convoys, Alabama’s is among the largest. This is so for a number of reasons: for starters, because so many Alabamians are football addicts, and because the state’s geographical position—within a half day’s drive of the campuses of most of Alabama’s Southeastern Conference foes—makes RV-ing practical. The weather is a factor too; in the South, it doesn’t get particularly cold until December, so fans cans tailgate comfortably for most of football season. At a typical Alabama game, between 250 and 800 motor homes show up, depending on the opponent and the venue. If you have never seen 800 motor homes in a single place, let me tell you, it is a strangely impressive sight. Consider that a motor home is exactly as big as its name suggests—it’s as though someone put four wheels and a transmission on a standard American two-bedroom ranch dwelling and drove it off the lot. Eight hundred of these things amount to a modest-sized American neighborhood; and here’s the thing—most of the time, these modest-sized neighborhoods are being driven into towns that already have neighborhoods, towns like Oxford, Mississippi; Gainesville, Florida; and Athens, Georgia. When hundreds of motor homes appear in one of these idyllic college towns, well, invasion is just too measured a word. The vehicles cram together in tight little perpendicular clusters, like bacilli in a petri dish, and fill every available empty space. It’s not unheard of for a visiting team’s motor home convoy to shut down an opposing team’s town with a weekend-long traffic jam—totally overwhelming the place, confounding the local police, and causing university officials to abandon their well-conceived parking schemes. (To members of the convoy, this is considered the height of accomplishment.) At big games, motor homes are so tightly packed that a person could nearly circle the entire stadium by walking along their rooftops, although as I learned firsthand, you should never walk along the rooftop of a stranger’s motor home because there’s a decent chance he will shoot you.

At any rate, a local news crew is broadcasting from Legion Field. The camera pans across a parking lot and finally comes to rest on a massive contraption that has a name painted on its side like a ship: the Crimson Express. Motor homes come in three basic categories: the plastic ones that look like children’s toys, the large boxy ones that look like a country-and-western star’s tour bus, and the sleek aluminum ones that resemble a 737 with the wings lopped off. The Crimson Express is of the 737 variety. The reporter boards the craft and finds the owners, a middle-aged couple who seem entirely too subdued to own something as outrageous as the Express. The husband is thin and tan, with a perfectly maintained plank of hair on his head. He bears a striking resemblance to the country singer George Jones. His wife too is thin and tan, and oddly, she looks a bit like Tammy Wynette, who was once married to George Jones. The reporter probes the couple’s devotion to Alabama football, and they say they haven’t missed a game in about fifteen years. So the reporter idly asks what sort of things they’ve given up in pursuit of the Tide.

Let’s see, the man says in a soft Southern drawl. We missed our daughter’s wedding.

You what?

We told her, just don’t get married on a game day and we’ll be there, hundred percent, and she went off and picked the third Saturday in October which everybody knows is when Alabama plays Tennessee, so we told her, hey, we got a ball game to go to. We made the reception—went there soon as the game was over.

I’d wandered through the motor home encampment at Alabama football games since I was a kid, but until I saw the local news that night, I’d never thought much about what was really going on. People were taking their houses to football games—packing up their lives in big rectangular canisters, driving for hours or days at a time in order to live as close to games as possible. And not just that, but if the owners of the Crimson Express were to be believed, they were also taking their homes to football games, in the sense that that word suggests the locus of one’s emotional comfort and well-being. I couldn’t help comparing my own devotion to Alabama to that of the owners of the Crimson Express; I felt suddenly inadequate. I didn’t remotely measure up. But it was clear that the same mysterious fascination that compelled me to listen to football games on the telephone moved others to totally rearrange their lives, to uproot themselves, and to shelve their familial obligations. But where did that fascination come from?

* * *

It would be easy, perhaps, to dismiss such hardcore fans as freaks, except for the fact that the world is practically brimming over with them. Open your daily paper’s sports pages to the box scores. You might want to pause and ask yourself why your hometown paper devotes an entire section to sports. The implication is that the readers’ need to know the outcome of sporting contests ranks up there in importance with their need to know about global politics, business and the arts. Compare that with the amount of column inches per week on religion; it’s not even close.

For each box score, consider how many moods hung in the balance over the game’s outcome. Maybe tens of thousands attended in person. They may have “gone wild,” or “gone crazy,” in the telling clichés we use to describe the behavior of fans. Thousands more—millions more if we’re talking about a big play-off game in some sports—watched at home or listened on their car radios. If it was a close game, it’s possible that some of these people had the most intense emotional experiences of their lives, more acute than anything they’d felt at home with their spouses or kids. If this sounds like hyperbole, think of the most emotionally intense moments in your own life—when you realized you were in love, when your child was born, or when someone you cared for accomplished something important, like graduating from college. You were profoundly happy, but you probably didn’t hug the stranger sitting next to you. Most likely, you didn’t “go wild.” You probably didn’t tear down a goalpost.

Now look at all the other box scores in sports pages and consider how many hundreds of thousands of Americans were on similar trips last night. Think about all the newspapers published in the world today, all their sports pages and box scores. Now think, if you can grasp it, of all the people in the world last night who watched sports. America has football, baseball, and men’s and women’s basketball. Europe, South America, Africa, and parts of the Middle East have soccer. Canada and Russia have hockey. The Japanese like baseball too, and also Sumo wrestling; Pakastanis, squash and cricket. Car racing is popular the world over. In Afghanistan there is a traditional game that involves two teams fighting on horseback for control of a ram’s carcass. There’s probably some kind of box score for that. (Cowboys 10, Rams nothing?) It’s dizzying, especially when you realize that what you just got your head around was one day’s worth of sports in the world, and that the cycle will repeat itself this evening. Millions more moods will hang in the balance, and the papers tomorrow will be full of another round of box scores. And so on, like the tides.

Given the torrential emotional outlay contests inspire on a daily basis, it’s amazing that human beings find time even to govern themselves. And yet—what is at the heart of every democracy but yet another contest—elections. We’ve even adopted the lingo of sports to describe our politics—the campaign is a “race”; and debates are scored like boxing matches. Constant polls amount to a sort of real-time scoreboard; election day is the buzzer. Perhaps this is the secret enduring quality of democracy: whichever way the ideological winds may be blowing, the public is always hungry for a good race. Even our judicial system is powered by contests—what is a trial but an intellectual sporting match? Everywhere you look, it seems, humans are compulsively gathering around to watch two sides battle it out. In this context, it was hard to see the couple aboard the Crimson Express as doing anything but steadfastly pursuing a universal human urge, third perhaps only to hunger and sex in its power over humankind.

For over a decade, whenever the subject of fans came up, I deployed the story of the wedding skippers as a kind of archetypal example of how far people would go. There was something interesting about the way people reacted. Most seemed to think the couple aboard the Crimson Express were nut jobs, or worse. Some used terms like “child abuse,” or compared the couple’s passion for football to alcoholism. Skipping a child’s wedding for a football game for these people was simply beyond. To people in this camp the most disturbing detail of the story was that the couple had made the reception. They weren’t not talking to their daughter; the family hadn’t experienced some irreparable rift. They just weren’t missing football games for her.

A not insignificant few, however—an unscientific estimate would be 25 percent or so—had a different view: they blamed the daughter. These people wanted to know what kind of person would force someone they loved to make such a choice. Those who blamed the daughter usually shared something in common: they were fans too. If they knew anything about Alabama football, they were likely to condemn the daughter even more harshly for the simple reason that she had scheduled her wedding for the day of the Tennessee game. Tennessee is a huge Alabama rival. You don’t devote your life to Alabama football and miss the Tennessee game. Interesting too was that while those who thought the parents were bonkers usually reacted with a chuckle and a shrug, those who blamed the daughter were more likely to get angry over the story. When I told the tale to one hardcore fan I met in Florida, he shook his head woefully and said simply: “Bitch.”

Whatever someone’s reaction to the tale of the wedding skippers, other questions always seemed to follow: What exactly were the mechanics of devoting your life to college football? What did these people do for a living? You don’t have endless amounts of free time and $300,000 to spend on a motor home by doing just anything; and yet, people who have come into such bountiful trappings of leisure aren’t necessarily the kind of people you picture in motor homes at football games. And what about all those people in those other motor homes—what did they do? What familial sacrifices were they making? Was it possible to find someone out there whose attachment to a football team was more intense than his attachment to life itself? And the overwhelming question was, Why?

In the late spring of 1999, another team I’d foolishly adopted, the New York Knicks, lost in the play-offs. I should’ve been prepared—the Knicks always lost in the play-offs—but there I was again at the threshold of despair. I had a familiar internal dialogue: I blamed the players, then the coach, then the management, and of course the referees, and then I scolded myself for even bothering to care. Why was I letting something as far removed and trivial as a basketball game plunge me into a funk? It was a familiar, nagging question that still seemed to me as mysterious as it did years before when I’d first become aware of my susceptibility to sports.

A month or so later, I was visiting my family in Alabama when the wedding skippers came up with friends in conversation. More than a decade had passed since I had seen them on local television proclaiming their devotion to the Tide, and in the intervening years, I’d begun to doubt that they actually existed. Perhaps I’d imagined them as a kind of defensive hallucination to justify my own obsession. At any rate, I had some time to kill, and I wondered if I might actually be able to track them down.

One of the wonderful things about life in a moderately populated state like Alabama is that if you spend years driving around in a wingless 737 with Crimson Express painted on the side, people more or less know where to find you. I made a few calls to some Alabama fans I knew, and in no time at all, I had a name and phone number for the owners of the Crimson Express—or at least, a Crimson Express. The couple’s name was Freeman and Betty Reese, and they lived in a suburb of Birmingham called Trussville, barely half an hour from where I grew up. I picked up the phone, dialed their number, and after a single ring, a gentleman answered in a familiarly soft voice and with an air of puzzlement, as if he were surprised anyone had called at all. I introduced myself as a reporter working on a piece about motor homes and football, and asked if I had the owners of the Crimson Express. Indeed I had, Mr. Reese said. A few minutes later, I was in a car on my way to meet them.

The Reeses live in a new subdivision next to a golf course, and their house is easily located, thanks to the big 737 without wings parked in the driveway, facing out and ever ready, like a fire truck. When I pulled in, the Reeses emerged from behind a glass storm door at the front of their house and introduced themselves. They were both older than I’d imagined, white haired with thin, tan legs emerging from matching red shorts. Mr. Reese wore a golf shirt and Mrs. Reese wore an Alabama football T-shirt. Mrs. Reese apologized for the state of the yard; the house was new, she said, and they were just now settling in, having recently moved here from a larger house a few miles away. The move had gone smoothly, she said, but for one hitch: there wasn’t space enough in their new home for all their Alabama memorabilia; they’d had to put their entire “ ‘Bear’ Bryant room” into storage.

“Sometimes you just have to move on,” Mr. Reese said.

Mr. Reese gave me a tour of the interior of the Express—through the kitchen (larger than the kitchen in my New York apartment), the bathroom, and to the master bedroom in the rear with a queen-sized bed, all of it decorated in a faded red and cream color scheme, like that of a 70s disco. The driver’s seat of the Express sat in a kind of well, with a steering wheel the size of a hula hoop and nearly as many switches, levers, and gauges as an airplane cockpit. Mr. Reese pointed to a button and raised his eyebrows with an impish look.

“Push it,” he said.

I did: the Alabama fight song blared from the roof-mounted air horns at roughly the decibel level of a civil defense siren. As the tune played—and played—Mr. Reese gazed dreamily through the windshield, as though he’d been transported to . . . well, who knew? I had the distinct feeling it was a stadium someplace.

I sat on one of the banquettes facing Reese. We talked for a moment about the Crimson Tide’s chances next season. “I’m optimistic, Lord knows,” he said. It occurred to me that spending $300,000 on a motor home to follow your team in was nothing if not an act of optimism. Eventually, I got around to what I thought might be a sensitive question: Are you the couple, I asked Mr. Reese, who skipped their daughter’s wedding to go to the Tennessee game?

“Oh that,” Reese said, nodding, a little guiltily, it seemed. “ ‘Fraid so, yes sir. That’d be us. You know we made the reception—drove to it straight from the ball game.” He paused for a moment. “I’m still paying for it.”

“So why’d you do it?” I asked.

Reese collapsed his brow, pursed his lips, and nodded pensively, a look that suggested I’d asked a very good question, but not one he had ever pondered before in his life. We sat silently, except for the roar of the air conditioner, and after a long minute Mr. Reese shrugged and shook his head.

“I just love Alabama football, is all I can think of,” he said.

* * *

My meeting with the Reeses inspired me to look further into the mysteries of being a fan. I wanted to understand how and why something so removed from our lives—something that doesn’t affect our jobs, our relationships, or our health (hangovers notwithstanding)—affects us so much emotionally. It seemed to me at the time that whatever the answers, they would be writ large in a subculture that was built around fandom—the Alabama RV scene. My interest was not in the RV scene as an example of some eccentric, marginal freak show but as a tinctured version of whatever it was that motivated me to listen to football games on a telephone, and whatever it is that drives interest in all the box scores in today’s newspapers—the almost universal fascination with sports. I went back to New York, took a leave from my magazine job, and soon after set out to attempt to join the RV-ers, to see what came of it. This book is the result.

Finally, a disclaimer. More than once in the course of my research, I looked up from my notebook into the face of a fan who was curious—sometimes, malevolently so—about what I was writing. This exercise produced a number of friendships, several threats of violence, and on my very first weekend out—in Nashville at the Alabama-Vanderbilt game—an exchange that occurred in various forms perhaps a dozen times during the fall.

A fan in cut-off blue-jean shorts, an Alabama T-shirt, a mustache, and a cheek full of tobacco asked, “Whachu writin’?”

I’m researching a book about fans, I said.

So you just picked Alabama out of a hat, the man asked declaratively. You’re not like an actual Bama fan, right?

I’ve liked Alabama since I was a kid, I said.

A knowing smile crept across my interrogator’s face.

Ho. Ly. Shit, he said. You get paid to go to Bama games . . .

Not exactly, I said. I go to games as research and—

Don’t bullshit the bullshitter, good buddy. He was now vigorously patting me on the back. You get PAID to go to Bama games! Sunuvabitch. Hey boys! Y’all get over here. This fella gets paid to follow the Tide!

I then found myself surrounded by a group of people who treated me as though I had just unlocked the riddle of the meaning of life, and who wanted to know every last detail of the publishing business—that beneficent industry that funds people to follow the team of their choice so long as they agree to carry a notebook and pencil with them for the journey. At any rate, the disclaimer is this: I have every reason to believe the world will soon be flooded with works of a genre that might be called the Alabama fan travel memoir.

I accept blame only for this one.