Although Simon and Garfunkel did not plan any more records together, they worked in concert whenever Garfunkel was available. Simon enjoyed performing. ‘There’s pleasure in doing a good show,’ he told Record Mirror in 1971. ‘If you do a good performance and everything is right and people like it, then you feel you’re part of the whole rhythm of the evening. You’re a part of the audience and the audience is a part of you and we’ve all entertained ourselves. That’s great. The drag of performing is when you do it too often.’

But performing was taking its toll and it was clear that they would soon stop appearing together. Simon told the New Musical Express in 1971, ‘I was not so much bored with performing as bored with what I was doing. We were singing the required Simon & Garfunkel hits which realistically we had to do. We couldn’t say, “We won’t sing ‘Bridge’ again” as people want to hear it and if we’re going out on stage, we’ve got to do it.’

Paul Simon discussed his problem with fellow artists. ‘I was talking to Dylan about going out on the road. It gets boring to me because they want to hear “The Sound of Silence”. He said, “Well, I’d like to see you and if I came to see you, I’d want you to see you sing ‘The Sound of Silence’ and ‘Scarborough Fair’.”’ As Dylan rarely played his hits as they had been recorded, there was some hypocrisy in what he was saying, but no doubt it was delivered with his knowing half-smile.

Possibly Art’s presence amounted to more than just turning up to sing the songs. Wally Whyton certainly thought so: ‘Art’s part of the set-up is much stronger than most people realise. Art is an arranger. He has an arranger’s mind and he knows how to get the best out of Paul’s material. Without Art’s influence, Simon might not be the star he is today.’ Interesting thoughts, but hardly backed up by the album credits.

Simon said that such thoughts were nonsense. ‘Anyone who knows anything would know that this was a fabrication,’ he told Rolling Stone in 1972. ‘How can one guy write the songs and another guy do the arranging. Musically, it was not a creative team. Art is a singer and I am a writer, musician and singer. We didn’t work together on a creative level and prepare the songs. I did that.’

Garfunkel had by far the more distinctive name. To be known by your surname implies a certain gravitas and status (Beethoven, Mozart, Gershwin, Lennon, Dylan, Springsteen) but that could never happen with Simon. Undoubtedly Garfunkel possessed the easier name for promoting new product, and the question was, would Paul Simon continue to be the star he was without Garfunkel? We had to wait for the answer as Paul pursued other interests.

Paul Simon’s friend, David Oppenheim, was now in charge of arts education at New York University and he posted a notice in January 1970: ‘Paul Simon of Simon & Garfunkel has offered to teach a course in how to write and record a popular song. Only those who are already writing and have music and lyrics to show Mr Simon should apply.’ The course would run on Tuesday evenings from February to May.

Sixty-nine students applied and Simon held auditions for his pupils. Ron Maxwell and Joe Turrin, who had written a rock opera, Barricades, auditioned and were surprised that Simon couldn’t read music. In turn, Simon thought they were too advanced for his class.

Eighteen-year-old Maggie Roche and her younger sister Terre were working clubs in Greenwich Village and knew Dave Van Ronk. His wife Terri told them of Simon’s classes. They attended an audition and saw Simon arriving on his own. He heard their songs and said that they could join and not even pay. He told them that they had enough talent to win local contests but that they were not ready professionally.

There were fifteen students in Simon’s class and he was always casually dressed in baseball cap and jeans. It was a two way street: one student told Simon of a new folk singer he had seen, James Taylor, who was sensational. Simon checked him out and agreed. He told one student, Melissa Manchester, that she had been listening to too much Laura Nyro and Joni Mitchell. He advised, ‘Say what you have to say as simply as possible and then leave before they have a chance to figure you out.’

Although Simon couldn’t read music, he explained the circle of fifths to them and told them about working in thirds for harmonies like the Everly Brothers. He said that nails had to be a certain length for fingerpicking.

He would tell the wannabe songwriters of the pitfalls in making records and how to correct them. He explained, ‘That’s what happened to most of the San Franciscan groups in the early days. Fine live groups but they didn’t know anything about the recording studio and they couldn’t figure out why their records were bad. They had to learn the whole thing and they had to learn it while they were making their albums.’

Simon took the best of the students’ songs and then recorded them at Columbia’s studios. The course was very successful – well, the Roches and Melissa Manchester came from it. Simon enjoyed it very much, saying, ‘I like talking about songwriting.’

Simon brought in Isaac Stern and Al Kooper as guest speakers but not Art Garfunkel, who was on a long holiday with Linda Grossman. They went to Tangier, Gibraltar and London, often hitchhiking. They rented a house in Oban, Argyllshire. He posed with sheep for the Oban Times and said he loved stone walls, green hills, long rambling walks and chatting with strangers.

While Simon was teaching and Garfunkel was travelling, the album, Bridge Over Troubled Water, was released. What group today would be permitted to do that? Nevertheless, the album sold a million copies within a week. Some concert dates were planned including five European dates in London, Copenhagen, Paris, Amsterdam and another in London over a fortnight. Except for Larry Knechtel, there would be no other musicians, but it would be a semi-holiday as they would have Linda and Peggy, two girls from Tennessee, with them. Garfunkel insisted that they stayed at the Amsterdam Hilton like John and Yoko.

Simon and Garfunkel returned to the Royal Albert Hall in April 1970. The demand for tickets was enormous and some had been touted at fifty pounds. They sang their hits but Simon noticed a difference. ‘It wasn’t like the audience of old friends who had been at the Royal Albert Hall before. They just seemed to be people who wanted to see a chart-topping act.’

Reviewing the concert for The Times, Miles Kington wrote, ‘My one criticism on Saturday was that they badly mismanaged their encores; there is no sight more depressing than squads of dumpy girls half-heartedly invading a stage.’

The concerts went well: they even managed ‘Fakin’ It’ with just a guitar. At the Royal Albert Hall, they sang two songs from Songs Our Daddy Taught Us – ‘Lightning Express’ and ‘That Silver Haired Daddy of Mine’. Miles Kington wrote, ‘Some hate Simon and Garfunkel because their music has no guts, because it is a middle class look at life, because it slips too easily from idiom to idiom.’

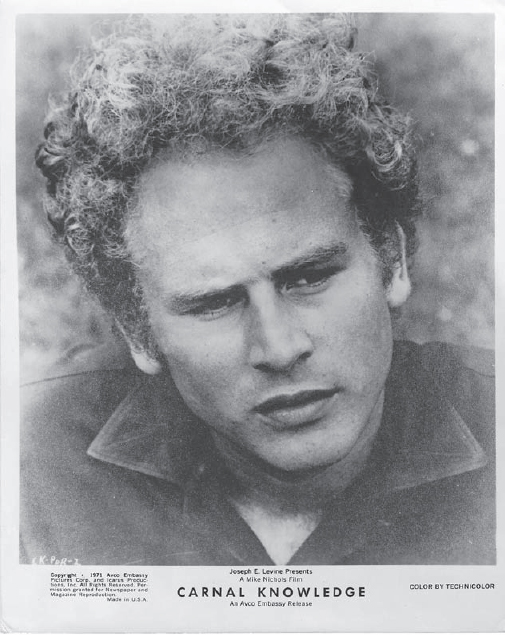

Miles Kingston considered their music gutless, but Garfunkel had made a film which broke social boundaries. With a title like Carnal Knowledge, the film had to be a send-up and it was. Mike Nichols was again directing and he worked from a brilliant funny/sad script from the cartoonist Jules Feiffer, the original title being True Confessions. Arthur (not ‘Art’, and he was similarly listed for the Bridge album) played someone with romantic ideals and he helped select the music for the film.

We start in the mid-1940s with two college students, the brash Jonathan (Jack Nicholson, and like Dustin Hoffman in The Graduate, looking too old) and the mild-mannered Sandy (Arthur Garfunkel) who are both determined to get laid. They make it with the same girl, Susan (Candice Bergen), and there is one splendid moment where Art introduces the condom to the big screen. Sandy marries Susan while Jonathan continues in his quest to find the Great Ball-buster of All Time. He finds her in the well-proportioned Bobbie (Ann-Margret) while Sandy has switched to Cindy (Cynthia O’Neal). As Cindy and Bobbie move away, Sandy and Jonathan become disillusioned and the film becomes serious. In a pitiful epilogue, Sandy grows long hair, acquires a hippy girlfriend and says, ‘I’ve found out who I am’, while Jonathan visits hookers for sexual excitement. Art had good notices, although John Weightman in Encounter, describing him as ‘ugly and sensitive’, was more hurtful than any criticism of his acting.

Jonathan and Sandy are two friends who are tough on each other, so shades of Simon & Garfunkel there. In reality, Garfunkel got on well with Jack Nicholson and they hosted a stoned viewing of Lawrence of Arabia in Vancouver. Art took the cast to a show featuring Joni Mitchell, Phil Ochs and James Taylor.

Carnal Knowledge was a far cry from anything Art had done before and it wasn’t long before a reporter – Lon Goddard of Record Mirror – wanted to know if Simon had seen Garfunkel’s movies. He replied, ‘Sure, I went with Artie. Catch-22 was a big disappointment for me but he was fine in his role. Carnal Knowledge is a good film – not a great one, but a good one and again Artie did very well.’

Writers looking back on the early 70s sometimes wonder why the Beatles split up: why couldn’t they have done their own things for a couple of years and then met up again? The answer is that no one had thought of a temporary break at that time, but that is what Simon and Garfunkel did. They had not ruled out working together, and Simon said, ‘We’re still good friends. We just have different interests, that’s all. There was never anything legal binding us… I don’t think that Artie wants a full-time career in acting. I think he’ll take parts that come along if they’re good, but he’ll keep singing.’

Although Art was a good actor, there were plenty of actors around and yet there were few singers with a voice as distinctive as his. There was no reason why he shouldn’t operate in both fields – after all, Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin and Elvis Presley had done that for years, and Kris Kristofferson was writing songs, recording albums and making films as though he had accepted some frenzied deadline.

In July they recorded a couple of other songs from that Everlys’ album, ‘Barbara Allen’ and ‘Roving Gambler’, in New York. Simon sang lead on a Scottish ballad, ‘Rose of Aberdeen’. It’s lovely, but this was made for their own entertainment rather than some specific purpose. As Simon once said, ‘I could sing these songs forever.’

But maybe not with Garfunkel. On 17 July 1970 Simon and Garfunkel played two shows at Forest Hills open-air stadium for a total audience of 28,000. They were paid $50,000 for their day’s work. They included the Bronx doo-wop hit ‘A Teenager in Love’, made famous by Dion and the Belmonts, and they combined ‘Cecilia’ with ‘Bye Bye Love’. They closed with ‘Old Friends’ and they agreed that this would be their final show, although they didn’t tell the audience or Mort Lewis. Just a few miles away at Downing Stadium on Randall’s Island, there was a huge New York Pop festival with Jimi Hendrix, Grand Funk Railroad, Steppenwolf, John Sebastian and Jethro Tull.

On 6 August 1970, Peter Yarrow of the then-splintering Peter, Paul & Mary had organised a show to raise money for the anti-war movement. The Summer Festival for Peace was at Shea Stadium with Creedence Clearwater Revival, Miles Davis, Big Brother and the Holding Company, and Paul Simon solo. It was the first time that music stars had got together for a large-scale political event. Garfunkel didn’t want to do it and Simon did it solo without consulting Lewis. Only 15,000 turned up, a huge audience but less than 30% capacity.

Their TV special notwithstanding, Simon was viewed as safe and old-fashioned. They started booing when Simon sang ‘Scarborough Fair’. Ellen Willis said in The New Yorker, ‘I hate most of his lyrics; his alienation, like the word itself, is an old-fashioned sentimental liberal bore.’

Simon judged a song contest in Rio de Janeiro and he came to the UK to resolve his publishing. The company that administered his catalogue had been taken over by Granada, who sold him their interest so that he would have complete control of his work. He said, ‘There’s nothing wrong; just that they’re my songs and I have a personal attachment to them.’

Roy Halee’s talents were appreciated by Columbia and in December 1970 he was asked to run their new studio in San Francisco. Meanwhile, Garfunkel had started teaching mathematics at Litchfield Prep School in Connecticut and was learning harpsichord. He and Simon met up with the Carpenters, Paul McCartney and Marvin Gaye at the Grammys in March 1971 but the duo hardly looked at each other. For a TV performance, Art Garfunkel found a new duet partner, the weather-beaten Harry Dean Stanton and they sang ‘All I Have to Do Is Dream’. Art appeared in a TV play, with Gene Wilder, Acts of Love and Other Comedies.

By late 1971, Simon had got round to a new album, his first solo recordings since The Paul Simon Songbook. He gave interviews while he was in the UK and he said that the album would simply be called Paul Simon. It had already been nine months in the making and he warned us against expecting too much: ‘I can’t follow Bridge and I don’t want to have to follow it. I hope I won’t get a feeling of disappointment for inevitably, what I do is going to be compared against that.’ At the moment, he was very happy with what he was doing.

The solo album was becoming a new marketing concept with bands breaking up and solo projects being initiated – Simon & Garfunkel, the Beatles, the Mamas & the Papas, Diana Ross & the Supremes, Crosby Stills Nash & Young, and the Monkees. John Sebastian of the Lovin’ Spoonful had been the unexpected hit at Woodstock, and all four Beatles had gone solo. Paul McCartney said of John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band, ‘The album knocked me out. It’s the first time I’ve heard his pain.’

But Simon preferred the throaty voice and brilliant slide guitar of Ry Cooder, who had just released his first album, Ry Cooder, in December 1970. ‘Nothing killed me as much as the Ry Cooder album. The Lennon LP is all right but Cooder is funkier.’

For all that, the John Lennon album is one of Paul Simon’s points of reference. Lennon was pioneering introspective, highly personal rock music. In their different ways, Marvin Gaye, Barbra Streisand and Don Everly had followed his example and looked inside themselves for their own albums. Paul Simon was going this way but without Lennon’s rants or self-indulgence. Perhaps to make his point, this new album had none of the lushness of Bridge Over Troubled Water.

Although Dylan’s sales were nothing like as substantial as Simon and Garfunkel’s, Simon knew that Dylan gathered more respect, and his appearance at Shea had brought that home. He wanted to make a solo album where he would not have to defer to a musical partner. Clive Davis supported him but felt that he was unlikely to sell as many records as just Paul Simon.

The success of Bridge had worked in Simon’s favour. Having had such a major success, he could record individual tracks wherever he thought fit. Since then there have been many globetrotting albums but Paul Simon was the first. He told Sounds, ‘I wrote the songs and I thought I’d like to do this with Los Incas or with Stéphane Grappelli and so I’ll go over to Paris.’ As a result, tracks were recorded in France and Jamaica as well as New York and San Francisco. Columbia used the diversity as a sales pitch:

Simon and… Stéphane Grappelli

Guitarist Jerry Hahn

Pianist Larry Knechtel

A reggae band from Kingston, Jamaica

A couple of Brazilian guys (!)

A few Puerto-Rican percussionists

(But not Art Garfunkel)

And he’s got into a whole lot of new things –

without losing any of the brilliance

of ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’.

This is a strange ad for several reasons. Firstly, it treats the whole thing as a novelty. Secondly, the exclamation mark is theirs, not mine. Thirdly, they are pushing the record by drawing attention to the very ingredient that is missing – Art Garfunkel. Fourthly, they’re inviting comparisons to ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’ even though they know this is something very different.

It’s worth commenting on the lack of Garfunkel: was he needed? At first, Simon said, ‘I don’t know. They’re different songs, a little funkier and harder.’ By the time the album was released, Simon said, ‘Artie could have sung any of the songs on the album.’ He described the change in recording practices, telling Sounds, ‘I did find it a little strange at first, not asking for an opinion and having his presence there, but after that initial feeling, I found it perfectly comfortable. Easier in a way because there were no conflicting opinions.’

Simon told Rolling Stone, ‘Since I don’t write well enough to orchestrate for strings, it means that I have to use an arranger and that moves it one step away. Consequently I have no interest in strings because they are not me – they have nothing to do with me. If it’s a great string part, then somebody else wrote a great string part. Here, I’m playing on almost all the cuts or else I know the people who are playing on them.’

Simon & Garfunkel never went for lavish cover art and indeed, their covers are amongst the dullest of the 60s. Simon’s new solo album was a close-up of his face with the hood up on his parka, but nevertheless, it has become a familiar image.

Despite the fact that several tracks were recorded around the world, this is still a New York album with Paul Simon writing about himself and his neighbourhood. The comparison would be with Woody Allen, who makes New York films no matter where he is working.

The album itself opens energetically with ‘Mother and Child Reunion’, a song he recorded at the Dynamic Sounds Studios in Kingston, Jamaica. He had wanted to go where Jimmy Cliff had recorded ‘Vietnam’. He told Melody Maker, ‘I like reggae. I listen to Jimmy Cliff, Desmond Dekker, Byron Lee – I send over to England for all those Chartbusters albums. I like ’em! I get off on it. So I say to myself, “I love it so much, I’m gonna go to Kingston, Jamaica.” I’m happy because I am playing with some different musicians and it turns me on.’

The rhythm is so catchy that you almost forget the lyric. The title comes from a dish of chicken and eggs that was on the menu at a Chinese restaurant. However, Simon is singing about a death in the family. Despite his sadness, he looks forward to the reunion, even contemplating suicide. He told Robert Christgau for Cheetah, ‘Last summer we had a dog that was run over and killed. I felt this loss – one minute there, next minute gone – and my first thought was, “Oh man, what if that was Peggy? What if somebody like that died?”’

The song is carried along by a pulsating rhythm and was an obvious single. It became an international hit, though not on the scale of ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’ (US 4, UK 5, Ireland 15, Germany 23) and a few months later the musicians he used were in the UK, this time backing Johnny Nash under the name Sons of the Jungle. In 2000, the song was used to good effect in The Sopranos (Series 2, Episode 2) to highlight the differences between Tony and his mother.

The next track is ‘Duncan’ and as soon we hear the first line, we know we are into something good. Lincoln Duncan is brooding in his motel room and he recalls various incidents in his life. The goings-on next door remind him of his first sexual encounter and he talks of making it with a female preacher. The Latin American sound comes from Los Incas, and overall, it is reminiscent of ‘The Boxer’. If it had had something similar to the ‘lie-lie-lie’ chant, it could have been a big single.

At least two critics (Jon Landau in Rolling Stone and Tony Palmer in the Observer) used the title of the third song, the bluesy ‘Everything Put Together Falls Apart’, to summarise the album but it was good work. This particular track is decent enough but the song is unexceptional by Simon’s standards. Its message is that you should control the drugs you take or they will be controlling you.

We retain that mood for ‘Run That Body Down’ but here the lyric, melody and presentation are better. Simon’s doctor has warned him not to do too much and he passes this message on, first to his wife and then to all of us. There’s some gentle humour in his asides and some lovely crooning in the ‘What’s wrong, sweet boy?’ section. This track is a tour de force and part of its strength could be attributed to Simon following medical advice and giving up smoking. He said, ‘It’s easier to sing. My range went up; it’s easier to hold a note.’ Even so, Simon can sound strained in the higher register, something Garfunkel could have done with ease.

Continuing with the blues, there is the melancholic ‘Armistice Day’, which completes the first side. The concept of contrasting love and war is hardly new, but it is a good song. Simon considered it the weakest song on the album. He had written it in 1968, preferring to use the former name Armistice Day instead of the current Veterans Day.

The second side opens joyously with ‘Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard’, which updates ‘Wake Up Little Susie’. There’s a section in that song about what Susie’s mother would do if she finds they’ve been out all night. Here she has and this time, the couple hasn’t just slept through a dull movie.

There is a powerful backing from guitar and drums, beautifully engineered to cover the changes in tempo and volume. The words gush out and Simon tells an elaborate story with economy and humour. The girl’s parents are instrumental in having him arrested, but a ‘radical priest’ secures his release. The saga makes the newspapers and the protagonist cannot return home. It sounds more like a film pitch than a song and it is remarkable how much is crammed into three minutes. What’s more, there are excellent thumbnail caricatures along the way.

For the enhanced version of the album, Paul Simon’s original voice and guitar demo for ‘Me and Julio’ has been added. It includes some wordless vocals as he hadn’t completed the lyric. There is an early take of ‘Duncan’ with a slightly different melody and a different story, this time about a man who lost his job, more akin to Gordon Lightfoot’s style than his own.

The finished take of ‘Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard’ shows how the Everly Brothers could have updated their sound for the 70s. Indeed, the toughest competition that Simon & Garfunkel could have had in the late 60s would have been the Everly Brothers if they had been on top of their game and hadn’t let it slide.

The Everlys’ influence on Simon and Garfunkel and indeed the whole of popular music is enormous. Bob Dylan has said, ‘We owe these guys everything. They started it all’, and that is hardly overstatement. Dylan paid homage by recording ‘Let It Be Me’ and ‘Take a Message to Mary’, while Simon and Garfunkel cut ‘Bye Bye Love’ around the same time.

The Everly Brothers fell from grace largely through brotherly bickering which led to them going through the motions and recording mediocre material indifferently. Eventually, they saw what was going wrong and made Roots (1968), and two superb singles in the same year, ‘Lord of the Manor’, the quirkiest of quirky songs, and ‘Empty Boxes’, which sounds like Simon & Garfunkel. By then it was too late and although they made two fine albums for RCA, Stories We Could Tell (1972) and Pass the Chicken & Listen (1973), not many people were listening.

When Simon was working with Puerto Rican musicians, he wanted them to play on ‘Me and Julio’. That didn’t work out but he asked them to play something of their own. He enjoyed how the conga player, Victor Montanez, was playing dunk dunka dokka dunk dunka dokka dunk. He made a tape loop and wrote ‘Peace Like a River’. It has similar intentions to Ed McCurdy’s folk song ‘Last Night I Had the Strangest Dream’ but is not as obvious. It is an underrated Simon composition, but it was on the soundtrack of the Maggie Smith film, My Old Lady, and in 2015 it was revived beautifully by the former lead singer of the Persuasions, Jerry Lawson, for the opening track of his album, Just a Mortal Man.

We’re back to bluesy sounds for ‘Papa Hobo’, which features unusual harmonium effects from Larry Knechtel. Simon plays a hobo in Detroit who is determined to make something of his life. It begins with a good joke and continues with Simon justifying his intentions. Detroit is famous for manufacturing cars but the singer does not want to work on an assembly line. Ironically, he needs a car to make his getaway and he performs the song as he is thumbing a ride.

To help him on his way, ‘Hobo’s Blues’ is travelling music, a much-publicised collaboration between Paul Simon and Stéphane Grappelli. It’s very short (just eighty seconds) but wholly delightful. Lesser performers would have turned this into a ten-minute jam, but Simon knows that less is more. He knows when to take a back seat: the violinist is in front while he stands in for Django Reinhardt.

‘Paranoia Blues’ is a collaboration with Stefan Grossman, the singer/ songwriter who established a following through such albums as The Ragtime Cowboy Jew. Simon wanted to feature his bottleneck guitar playing and the result, ‘Paranoia Blues’, is another song about honesty and we move from the difficulties of living in Detroit to the difficulties of living in New York. The city is full of greed and Simon even has his meal stolen in a restaurant. Hal Blaine plays drums and Simon adds further percussion. Stefan watched Simon at work with his engineer, Roy Halee: ‘When these two have a song, they get it done well. When Dylan is in the studio, he gets three takes done and that’s it, but Paul keeps at it and takes a lot of trouble.’

Donald ‘Duck’ Dunn of Booker T. & the MG’s would agree. He helped Paul record ‘Congratulations’, the final track on the album, which involved many takes. Paul scrapped them all and redid it with Larry Knechtel. It was worth Simon’s perseverance as it is neatly concludes the album.

On this side of the album, Paul had been travelling. The singer is shown as dissatisfied with life in Detroit and New York and even when he is content, as in ‘Me and Julio’, he is forced out of town by circumstance. This time he is a little more positive in his search for America.

In ‘Overs’ on Bookends, a man didn’t have the guts to leave his wife. On this album, in ‘Congratulations’, he leaves, and it’s a wonderfully ironic title. Simon is melancholic about his society spawning so many divorces and his voice breaks with sadness for the final question, asking whether peaceful co-existence is possible. Simon wasn’t perturbed about the pessimism of so many of his songs. ‘I love my own music,’ he admitted to Time. ‘I can sit and play the guitar all night and I love it because it’s me and I’m making it all up.’

Paul Simon was a No. l album in the UK (replacing Neil Young’s Harvest) and No. 4 in the US. Columbia released a story which I like to think is accurate. ‘This is one of the albums that President Nixon took with him on a trip to China. Chairman Mao (who is the most important poet in the eastern world) was reportedly knocked out.’

As Simon did not share Nixon’s Republican views, he appeared at fundraising concerts for Senator George McGovern. One was at Shea Stadium in August 1971. ‘It embarrassed me to be at Shea Stadium,’ he told Sounds. ‘I felt stupid. The sound system was bad. The artistic side becomes unimportant: you’re just somebody who can raise money. We went to the biggest of venues and people were charged the highest of prices.’

Nevertheless, he was back there in April 1972 for a concert also featuring Joni Mitchell, Phil Ochs and James Taylor. This extract from The Cleveland Scene indicates that the sound was probably worse: ‘Paul Simon started with “Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard” followed by “Congratulations”. He made a few short pleas for silence, had a few choice words for the police and the ushers, and, finally realising the hopelessness of the situation, he gave up. No more unfamiliar songs, no more fancy guitar work. He half-heartedly strummed half a dozen of his hits and walked off. It was sad. It was Paul Simon doing a mediocre imitation of Paul Simon.’

Paul was, nevertheless, fundraising at Madison Square Garden on 14 June 1972, this time reunited with Art Garfunkel. Rolling Stone reported, ‘When Simon and Garfunkel came out, they looked as if they hadn’t spoken in 12 years. Dressed in jeans and baggy sweaters, they stood at their mikes looking straight ahead like two commuters clutching adjacent straps on the morning train.’

Such reports hardly sounded encouraging but Simon and Garfunkel did consider touring again. As Paul told Roy Carr in New Musical Express, ‘Certainly I’ll do solo concerts, but I wouldn’t rule out singing with Artie again. There’s no animosity there and no rigidity either. The difficulty was structuring everything into Simon & Garfunkel. That was impossible.’

Columbia must have been sorry that the group split up and would have welcomed another album from the duo. In its place they put out Simon and Garfunkel’s Greatest Hits, which was partly issued to combat bootleggers who were releasing their own compilations.

The album is unusual in that Columbia chose some of the songs in concert performances. They were the first official live recordings of Simon & Garfunkel’s hits to be released. They chose ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’, ‘For Emily, Whenever I May Find Her’, ‘Homeward Bound’, ‘Kathy’s Song’ and ‘The 59th Street Bridge Song (Feelin’ Groovy)’, though it’s hard to tell as both ‘Bridge’ and ‘Kathy’s Song’ open with applause and end with none. I suspect that Simon himself had some hand in the compilation as some of the songs that he had second thoughts about (‘A Hazy Shade of Winter’, ‘The Dangling Conversation’) are omitted in favour of ‘Kathy’s Song’ and ‘America’.

With a bizarre flourish, ‘America’ was released as the group’s next single although it had been available on Bookends for four years. It only made No. 97 on the US Hot 100 but it climbed to No. 25 in the UK, thereby justifying its release. It was primarily a platform for the album. Maybe some were not aware that it was an old track as Ed Stewart heralded it as their great comeback single on the BBC’s Junior Choice. The album itself made No. 5 on the US album chart and hung around for five months, but it went to No. 2 in the UK and remained on the listings for over five years, thus keeping the Simon & Garfunkel flame alive.

Although Art Garfunkel had no new film commitments, the projected plan for a Simon & Garfunkel tour evaporated. Sharing backing vocals on a few of Simon’s solo gigs was Carly Simon (no relation) who had been friendly with them for some time. When she released her sardonic masterpiece ‘You’re So Vain’ there was much speculation as to whom the song was addressed: Warren Beatty, Mick Jagger, Kris Kristofferson and record mogul David Geffen were all contenders. In 2015, Carly Simon admitted that the first verse was about Warren Beatty, but she didn’t say anything about the rest.

Simon could have been a contender himself when he came out with such choice quotes as this, said to Rolling Stone in July 1972: ‘Many times on stage, though, when I’d be sitting off to the side and Larry Knechtel would be playing the piano and Artie would be singing “Bridge”, people would stomp and cheer when it was over and I would think, “That’s my song, man. Thank you very much. I wrote that song.”’