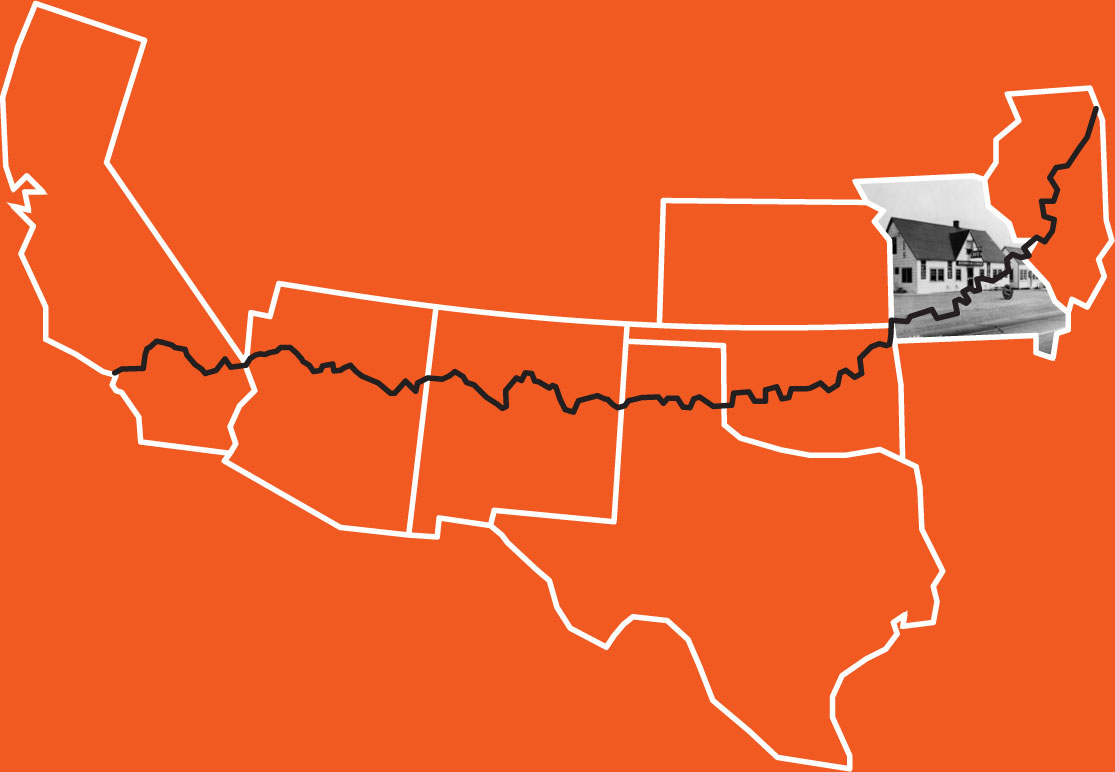

c. 1942

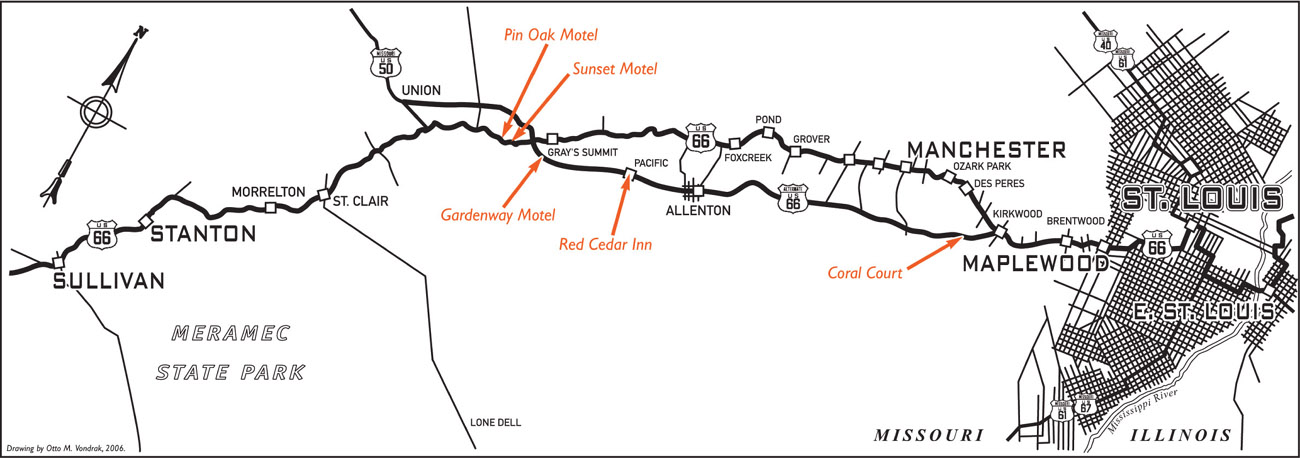

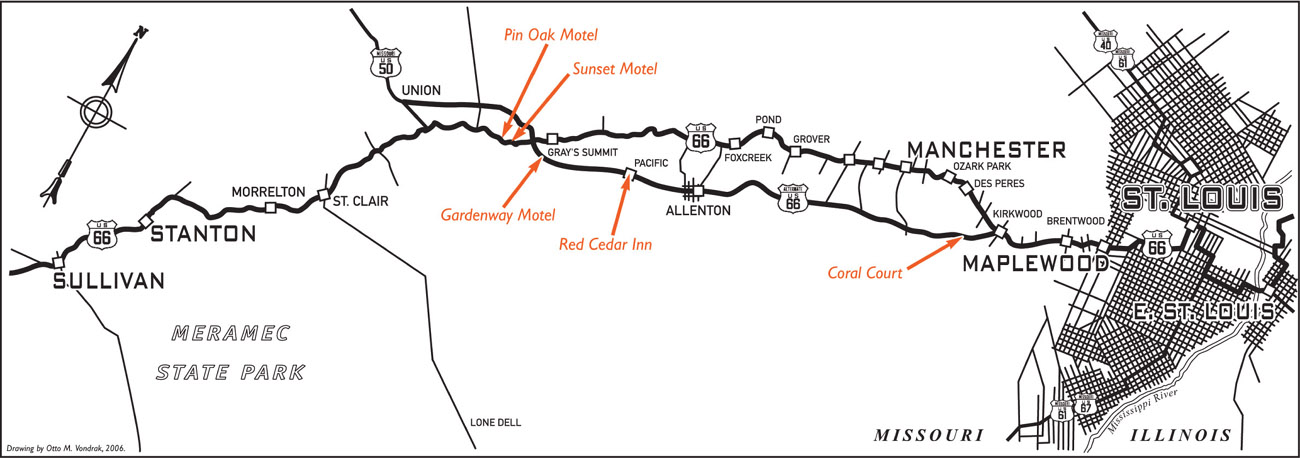

John Carr built the fabled Coral Court just outside the city limits of St. Louis. The motel was painstakingly designed by architect Adolph L. Struebig, and construction began in summer 1941. By early 1942 the Coral Court greeted its first guest. Ten single-story units, with two rooms and two garages per unit, and an office structure were included. Almost immediately the Coral Court became a standout. The Streamline Moderne style, the elegant veneer of ceramic-glazed brick, and artful glass-block windows made it one-of-a-kind.

In 1946, 23 additional units designed by architect Harold T. Tyre were built using the same materials and varying only slightly from the original ten units. The new units featured triangular glass-block windows, but the overall look of the Coral Court remained. Another expansion took place in 1953 with the addition of three more ordinary-looking two-story units, also designed by Tyre, at the rear of the property. A swimming pool was added in the early 1960s.

Carr died in 1984, leaving the Coral Court to his wife, Jessie, and head housekeeper, Martha Shutt. Jessie and her second husband, Robert Williams, operated the business until August 20, 1993. Over time a lack of maintenance took its toll. During its later years the Coral Court began a swift decline, even garnering quite a racy reputation. The fact that you could park in a garage, close the garage door, and enter the unit from inside the garage made the Coral Court a perfect rendezvous for star-crossed lovers. No guest vehicles were visible to jealous spouses driving through the grounds. As if that weren’t enough, rooms could be rented in three-hour blocks.

Beginning in 1987 preservation groups fought to save the Coral Court from an untimely demise. The Coral Court was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on April 25, 1989. Sadly, the motel, except for one unit, was demolished in June 1995, and the new owners, Conrad Properties, began construction of the Oak Knoll Manor on the old Coral Court grounds.

Jessie (Carr) Williams passed away on October 15, 1996, a year after the razing of the Coral Court (Robert Williams had died on May 18, 1994).

The Coral Court’s history is full of wonderful stories and anecdotes, which are covered in detail in Tales from the Coral Court by Shellee Graham. Luckily for fans of the Coral Court, the Missouri Museum of Transportation, with help from many volunteers, worked for weeks to disassemble a complete Coral Court building prior to the rest of the motel’s demolition. The building was stored at the museum and rebuilt in all its glory, so that future generations will be able to view this work of art that just also happened to be a motel.

c. 1941

Brothers Bill and James Smith built the Red Cedar Inn in 1934 out of red cedar logs, which were cut from the family farm in nearby Villa Ridge and hauled to the construction site on a Ford Model AA truck. The structure’s logs were all hewn with an ax, while the foundation was dug using mule power.

Soon after the inn’s opening, sometime in 1935, a barroom was added to the facility. During the early years the inn offered gasoline service from two pumps out front. The sale of gasoline was eventually halted, and all efforts were focused on the restaurant business. In 1935, acting as manager of operations, James Smith II hired 19-year-old Katherine Brinkman to wait tables. It was the hiring of his life—the two soon fell in love and were married in 1940. Katherine and James II eventually purchased the business from his father in 1944. Alongside son James III and daughter Ginger, the couple ran the business until James II retired in 1972. In 1987 Ginger and her father reopened the Red Cedar Inn with a little help from Katherine, who continued to bake the restaurant’s delicious brownies.

The Red Cedar Inn was a classic example of the family-run businesses that proliferated on the highway during the glory days of Route 66. These businesses were slapped together with guts and hard work. Some continue to operate today, requiring even harder work to survive. Like the Red Cedar Inn, many have been handed down from generation to generation. Officially listed on the National Register of Historic Places on June 22, 2003, the Red Cedar Inn unfortunately ceased operation in 2005 and was up for sale at the time of this book’s publication.

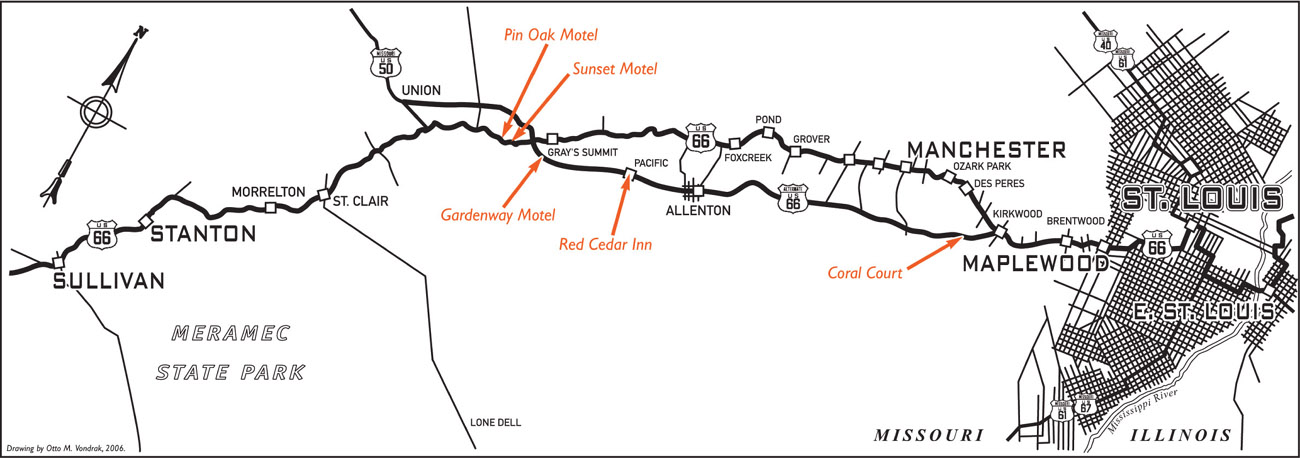

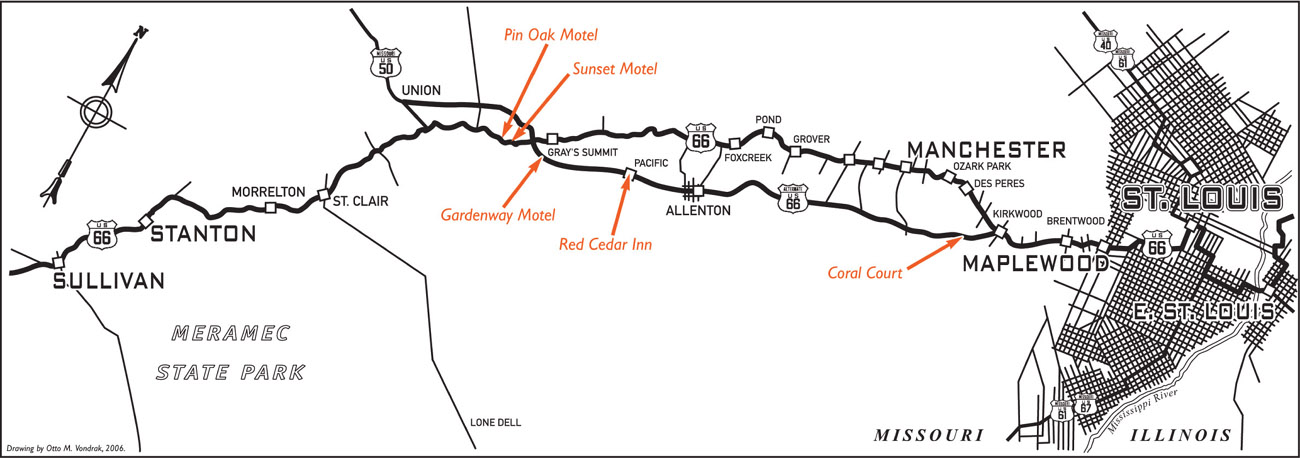

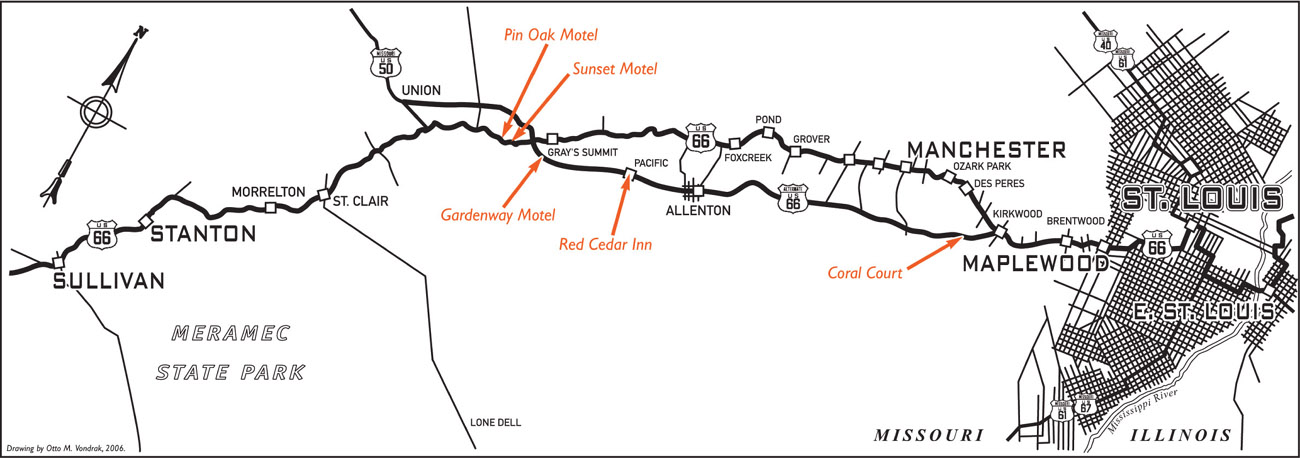

c. 1950

On the 30-mile stretch of Highway 66 between St. Louis and the Missouri Botanical Garden Arboretum at Gray Summit, the roadside was once lined with thousands of decorative shrubs, lush trees, and native flowers. The National Park Service and the Missouri State Highway Commission, in conjunction with the Missouri Botanical Garden, combined forces to create this remarkable landscaping and preserve the natural indigenous plant life of Missouri for future generations. Billed as the Henry Shaw Gardenway, in honor of the man who founded the Missouri Botanical Garden back in 1858, the project was completed in 1937.

In 1945 Louis B. Eckelkamp built his Colonial-style motel at the western edge of the Gardenway, near his home and adjacent to the Missouri Botanical Garden Arboretum. By 1954 the Gardenway Motel featured “Twenty-five Modern Cabins with Tile Baths.” The motel eventually grew to also include 41 guest rooms.

The beautiful Streamline Moderne Gardenway sign beckoning motorists near the edge of the road sits in stark contrast to the motel’s sprawling American Colonial architecture. When lit up, this sign stands out as the ultimate in classic Route 66 motel signage. Today the motel still waits patiently to serve vacationers and business travelers. The neon sign, on the other hand, waits to be brought back to life, longing for the flick of the switch that will once again breathe life into its colorful neon glass.

c. 1942

Built in the early 1940s, the 12-unit Sunset Motel stands out as one of the more distinctive motels of the era. Located 38 miles west of St. Louis, the Sunset was built of beige brick and laid out in a V shape in which the exterior center of the V served as a community area equipped with ice and soda machines. One of the more unusual aspects of this motel is the fact that it was built with two entrances per unit: one entrance in front of each unit overlooking a sprawling, beautifully landscaped lawn area, and the other providing entrance from the parking lot and driveway behind the structure.

Today the motel stands much as it did when it was built over 60 years ago. The original eye-catching signage also remains intact and over the years has evolved into a Route 66 must-see photo op. “Twelve Units, Twelve Baths, Panel Ray Heat, Beautyrest Mattresses and Quiet” was the advertising copy that attracted weary motorists to the Sunset. The interstate bypass in 1967 added an exclamation point to the word “Quiet,” and the Sunset Motel now sits empty and silent, fading in the golden twilight.

c. 1953

The Pin Oak Motel was built around 1940 some 40 miles west of St. Louis and was named for the beautiful pin oak trees that dominate the local landscape. The Pin Oak was originally laid out with two sets of two buildings. The buildings were joined by common carports and faced each other across a courtyard. Originally just eight units were available, but by the early 1950s more units had been added and the carports were enclosed. Eventually the room count grew to 28.

A member of the American Motor Hotel Association, the Pin Oak was billed as “a better court for better people” and was advertised as having “clean, ultra-modern units.” In the early 1960s, free air conditioning, free TV, and new carpets were added to the list of amenities. In 1967, however, Interstate 44 bypassed the area and, like so many other motels, the Pin Oak fell on hard times. Eventually converted into a self-storage facility, the old Pin Oak Motel stands as a relic to the glory days of Route 66, safely storing memories of its past alongside family treasures within its aging walls.

c. 1940

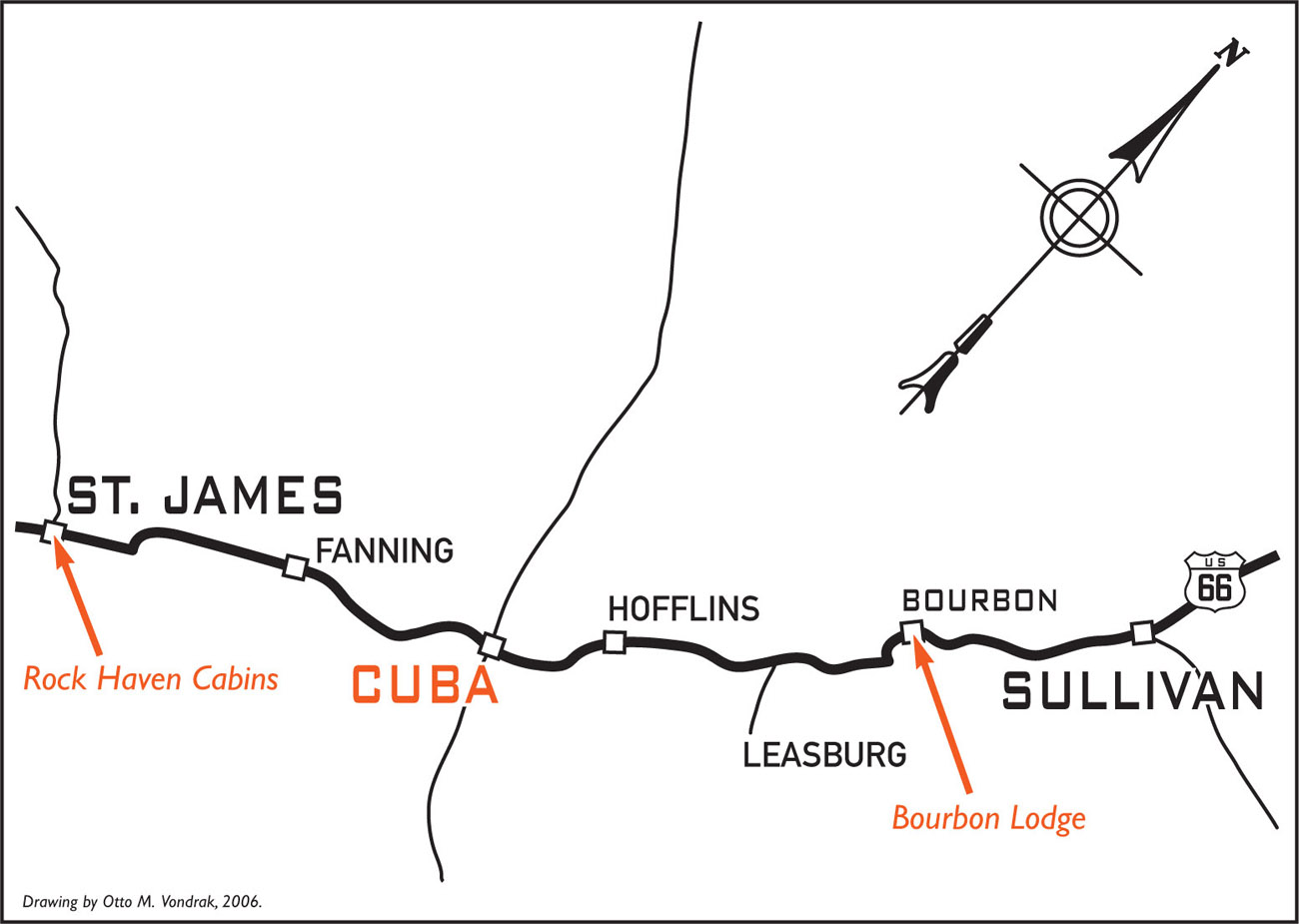

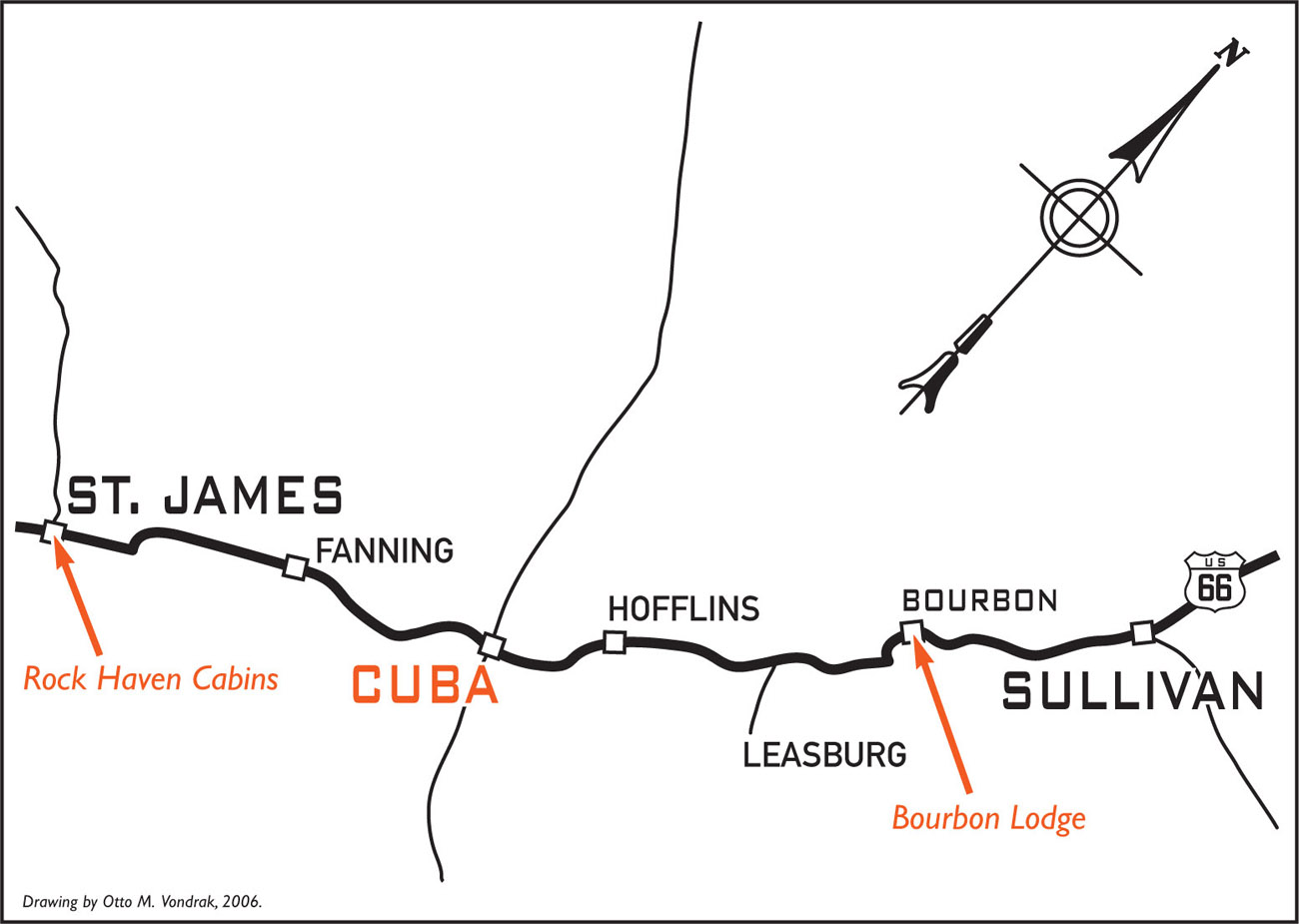

Sometime during the 1850s, a store owner by the name of Richard Turner began selling a popular “new” type of whiskey called bourbon to settlers and Irish railroad workers. It was served from barrels that sat on the front porch of his store, which soon became known as the Bourbon Store. It did not take long before railroad workers began to identify the entire area as Bourbon, and the name stuck. In September 1853 a post office was established, and the town became known as Bourbon in the Village of St. Cloud. St. Cloud was the name of a proposed town that was to be located 1 1/2 miles to the east, but which never came to fruition.

With the coming of Highway 66 in 1926, auto courts, cafés, and service stations popped up all along the highway in this region. In 1932, six years following the designation of Highway 66, Alex and Edith Mortenson opened the Bourbon Lodge. The small, fledgling operation included a café and three overnight cabins. The café featured a 25-cent breakfast that included bacon, eggs, toast, and coffee, while a cabin, sans indoor plumbing, rented for a whopping 50 cents per night. A Phillips 66 station was later added, as was a fourth cabin. By 1939 the Mortensons were charging $1 to $1.50 per night for the cabins, which now included indoor toilets and showers. The Mortensons eventually sold the Bourbon Lodge in the early 1940s and moved a half mile west on Route 66, where they owned and operated the Hi Hill Cabins and Station until 1947.

Many of the Bourbon Lodge structures still stand today, including the lodge/café building that now serves as a private residence. The service station and a couple of cabins remain in varying states of disrepair. The people of Bourbon are proud of their small, friendly town and have no aspirations to become hurry-up, cold-hearted, “big city” people. They prefer instead to be known as plain folks who like to make you feel at home.

c. 1936

Cuba had its beginnings in 1857 when two men, M. W. Trask and W. H. Ferguson, surveyed the town site in anticipation of the St. Louis & San Francisco Railway coming through the area. Responsibility for naming the town is said to have belonged to George Jamison and Wesley Smith. Smith suggested the name as a show of support for Cuban citizens, who were then under Spain’s oppressive hold. Jamison wanted to name the town for his wife, Amanda, who had a post office already named for her just 1 1/2 miles west of the new proposed town site. Legend has it that the issue was resolved by standing a stick on end and letting it fall. How the stick landed determined the town’s name.

The railroad played a vital role in the community’s growth, and Cuba served as a major shipping point. Apples were another major factor in Cuba’s developing economy until the early 1930s. When Highway 66 came through in 1926, things really began to explode, and by the 1930s the original town site was abandoned. Cuba moved away from the railroad tracks and closer to the new highway. It became a true highway town and much of its economy was based on the seemingly never-ending parade of tourist traffic. Motels, cafés, and service stations seemed to pop up overnight.

The interstate bypassed Cuba in the late 1960s, but the townspeople banded together to build a model community that is admired and emulated by many of Missouri’s rural towns. The citizens of Cuba are proud of their Route 66 heritage. Large banners hanging from light poles and murals decorating Cuba’s buildings celebrate the town’s link to Route 66. Known as the “Gateway to the Ozarks” and the “Mural City,” Cuba stands as a true Route 66 renaissance town and is a must-see when exploring the old road.

c. 1940

The Rock Haven is a classic example of a 1920s and early- 1930s motor court. These overnight rest stops provided simple, modest accommodations for tourists as well as traveling businessmen. Opened shortly after Highway 66 was designated a U.S. highway, the Rock Haven offered six small “modern” cabins built of native sandstone slabs known as giraffe rock. This rock was a common sight in the region and was used to build everything from homes and motels to filling stations and restaurants. Indoor plumbing was not typical of early motor courts and was, in fact, considered a luxury. The Rock Haven, like many original auto courts of the day, provided a community washhouse with hot and cold running water for showers.

In 1950 Frank and Ruth Waring purchased the Rock Haven and that summer added a wooden double cabin, a restaurant, and a new filling station that sold Standard Oil gasoline. In 1954 the Warings sold the business to Rudy Gilder, who operated the Rock Haven until the interstate bypassed it in the late 1960s. Converted to a nightclub and tavern in the 1970s, the restaurant building, although somewhat altered, is today a private residence. In 1988 all but one of the cabins were razed, leaving a small but tantalizing glimpse into the past of American auto travel and the halcyon days of Highway 66.

c. 1939

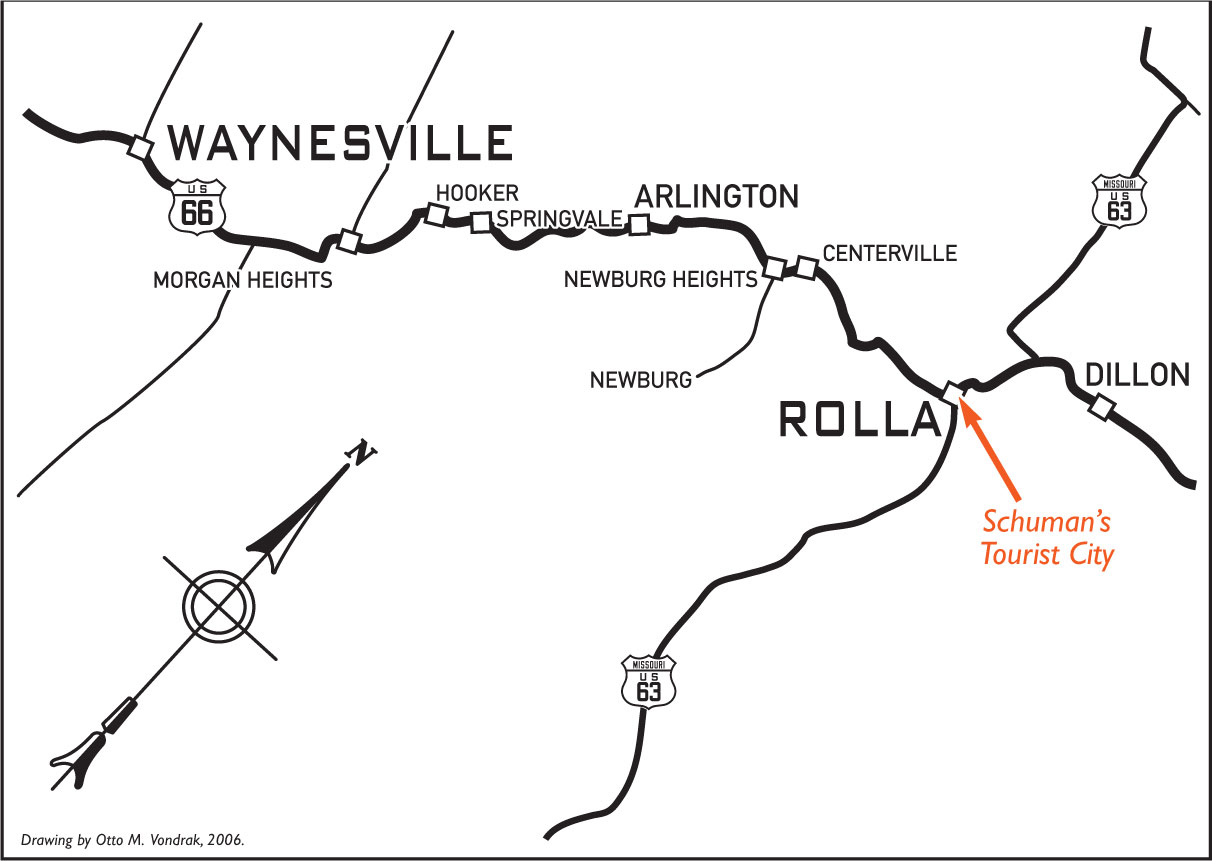

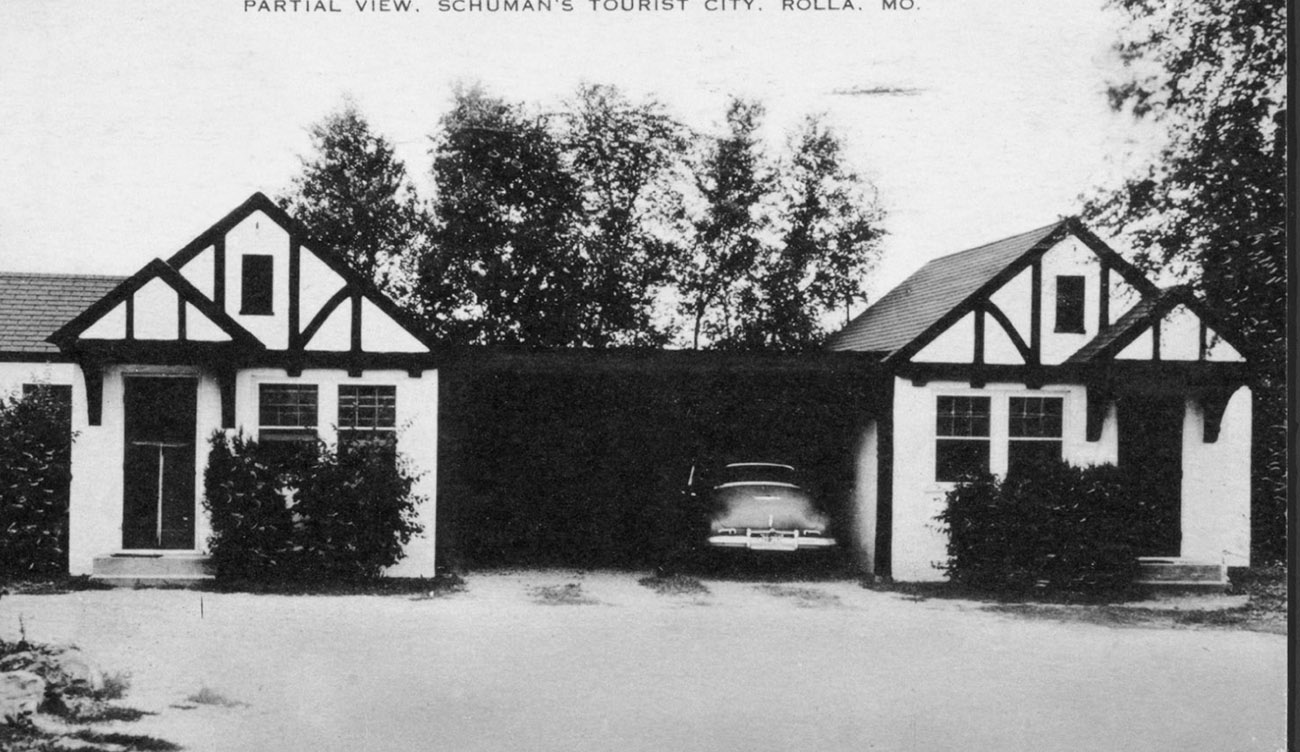

R. E. Schuman opened his “tourist city” in 1928, hoping to capitalize on the newly designated Highway 66 that ran through town. According to a quote from the Rolla Herald on June 27, 1929, “Seventeen clean comfortable cottages, ideally suited at the north city limits of Rolla, will cause thousands of tourists to stop in our city each season. It is a general comment of tourists that the Schuman Cottages are the nicest and cleanest along the highways.”

Originally known as Schuman’s Cottage City, then as Schuman’s Tourist City, the business was known as Schuman’s Motor Inn in the 1950s and 1960s. From the day the first cottages were completed in 1928, Schuman constantly made improvements to the guest units and to the grounds, adding conveniences such as covered parking, steam heat, radios, and telephones. By the late 1930s, Schuman’s Tourist City also included a service station, café, and a two-story hotel with accommodations for 100 guests. The hotel was billed as offering “all the facilities of a fine city hotel combined with the conveniences of an ultra modern motor court.”

In 1931 an armed gunman held up Schuman’s, leading the owners to hire a watchman to patrol the grounds at night. The patrolman carried a watch clock that he punched at designated stations throughout the grounds, covering “all parts of the court and all floors of the hotel,” as the back of a period postcard states.

Schuman became a prominent businessman in the Rolla area and owned several other businesses, including the Central Missouri Hatchery that turned out thousands of baby chicks a week, and a commercial flower garden located adjacent to the motel. Surviving well into the 1960s as Schuman’s Motor Inn, the former Tourist City eventually closed. Today its past is a distant, fading memory for thousands of tourists who made Schuman’s a unique “city” unto itself as they made their way to untold destinations along Route 66.

c. 1939

Ray Coleman and Blackie Walters built the 4 Acre Court in 1939 in the hopes of cashing in on the ever-increasing flow of traffic heading down Highway 66. To attract vacationing families, they built individual cabins with a fireplace in each. The cabins were “rocked” using the giraffe-stone exterior that was so popular in this region of the Ozarks during the 1930s and 1940s. For the more adventurous travelers, a campground was located to the west of the main building. This campground was eventually turned into a children’s playground. A two-story building out front served as the owners’ residence and office and at one time also housed a gas station and convenience store.

Today the one- and two-room cottages comprise an apartment complex called Village Oaks. In 2003 one of the cottages was destroyed by fire, but luckily none of the other remaining units were damaged.

c. 1940s

Joplin holds the honor of being one of the 14 Route 66 cities forever immortalized in Bobby Troup’s legendary hit song “Route 66.” Located on the Ozark Plateau in the southwest corner of Missouri, just 200 miles from the geographical center of the country, Joplin was established in 1848 and was once known as the lead and zinc mining capital of the world. It was named for Reverend Harris G. Joplin, who founded the first Methodist Church in Jasper County in 1840. Because of its central location, Joplin became a major shipping point for many of the country’s largest trucking companies.

Excessive mining has created many problems for the city, including a number of street cave-ins caused by the numerous abandoned mine tunnels under the city. As a result, Route 66 saw many alignment changes in Joplin over the years, including a City 66, Alternate 66, and a Bypass 66.

From 1979 to the route’s demise in 1985, the Joplin area was designated the easternmost terminus of Route 66. During the glory days of the Mother Road, Main Street in downtown Joplin was a bustling and thriving entity lined with huge department stores, no less than 20 hotels, banks, eight movie houses, and every type of shop imaginable. Back during Joplin’s rowdy mining days, an establishment called the House of Lords on Main Street advertised “fine cuisine, gambling and ‘soiled doves.’ ” Today the site of the notorious House of Lords is a city park, and most of what was downtown Joplin long ago moved to outlying malls. A few cafés, taverns, and specialty shops still serve the downtown area, but most of these struggle to survive.