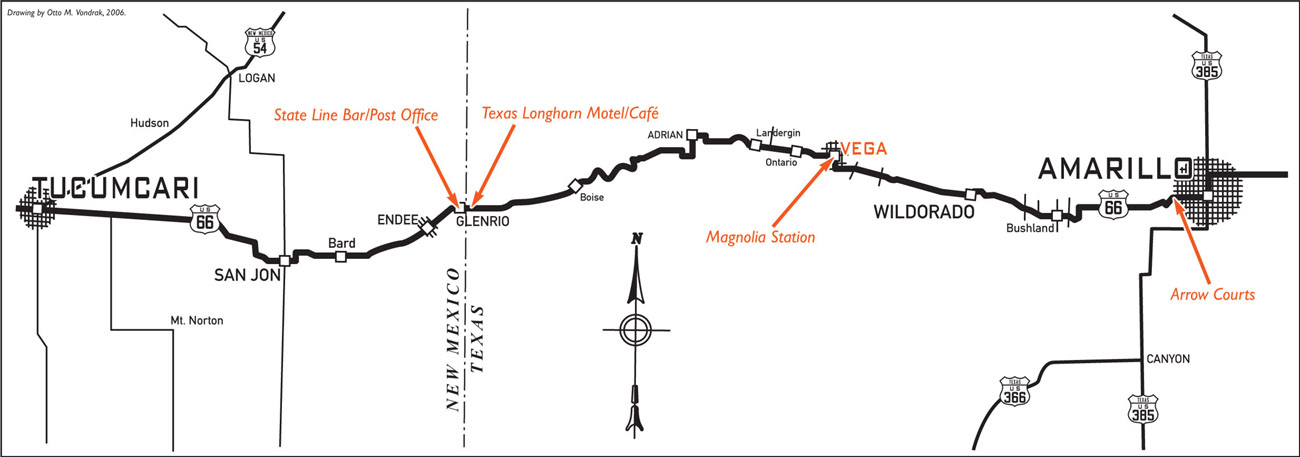

STATE LINE BAR/POST OFFICE, GLENRIO

c. 1943

Founded in 1903, two years after the Rock Island Railroad wound its way through the area, Glenrio quickly grew through the 1920s as an agricultural and farming community. The name Glenrio stems from the English word glen meaning “valley” and the Spanish word rio meaning “river,” though Glenrio is neither in a valley nor near a river. Glenrio straddles the Texas–New Mexico border, but the post office is in New Mexico. This caused confusion early on, because the mail was delivered to a depot on the Texas side of town. Connected to the post office was the State Line Bar, which was operated on the New Mexico side of town because Deaf Smith County on the Texas side was dry. The fact that the post office and bar are connected makes one wonder if the mail was ever delivered on time.

Highway 66 was still a dirt pathway through town when Homer Ehresman and his wife, Margaret, first arrived in Glenrio around 1934. The Ehresmans quickly went into business operating a service station, bar, and tourist court, while Margaret also ran the post office. By the fall of 1937 the dirt pathway running through Glenrio was finally paved. During the construction that ran from summer to fall, workers camped in tents alongside the road. By 1946 talk of a new interstate that would bypass Glenrio prompted the Ehresman family to pull up stakes (see the Texas chapter).

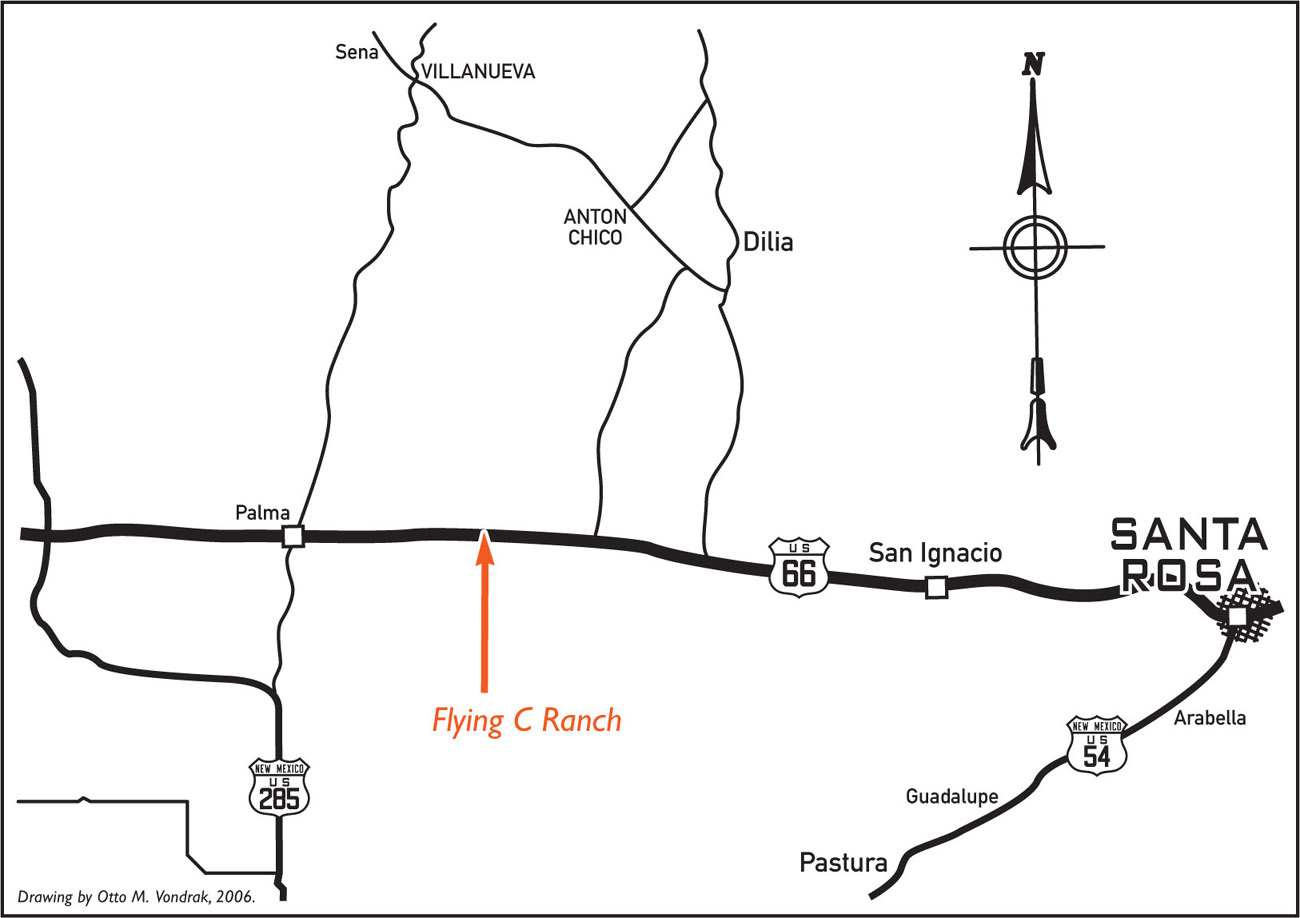

c. 1945

Located 77 miles east of Albuquerque, near a speck of a town called Palma, the Flying C Ranch was built in 1945 by Roy Cline, who is more widely known for establishing Cline’s Corners in 1933. In 1939 Cline sold the very successful Cline’s Corners and moved on to Kingman, Arizona. After a few additional pit stops, he returned once again to eastern New Mexico, where he built the Flying C Ranch.

The Flying C Ranch featured a garage complete with wrecker, a filling station selling Texaco gas, and a small café. Much of the Flying C Ranch’s business came from stranded motorists unaccustomed to traveling the Southwest’s desert during the hot summer months. After completing a few stucco repairs, Cline’s son painted one of the buildings stark white. The color attracted customers, and soon all the buildings were painted white. The Flying C developed into an all-purpose travel center when it became a regular stop for the Greyhound bus line.

Cline owned and operated the Flying C Ranch until 1963. Both Cline’s Corners and the Flying C Ranch remain in business today without the involvement of any Cline family members. The Flying C is currently owned and operated by Bowlin Travel Centers Incorporated. The Bowlins have been meeting the needs of the traveling public since 1912, when Claude M. Bowlin began trading with Native Americans of New Mexico. The Bowlins currently own and operate 12 travel centers, all located in the Southwest, three of them on Historic Route 66. Each full-service travel center offers gifts, souvenirs, exclusive handmade Indian jewelry, and gasoline. Many also feature Dairy Queen restaurants. In 1972 Bowlin’s youngest son, Michael L. Bowlin, became president and CEO of the operation and remains in charge to this day. Claude M. Bowlin died in 1974.

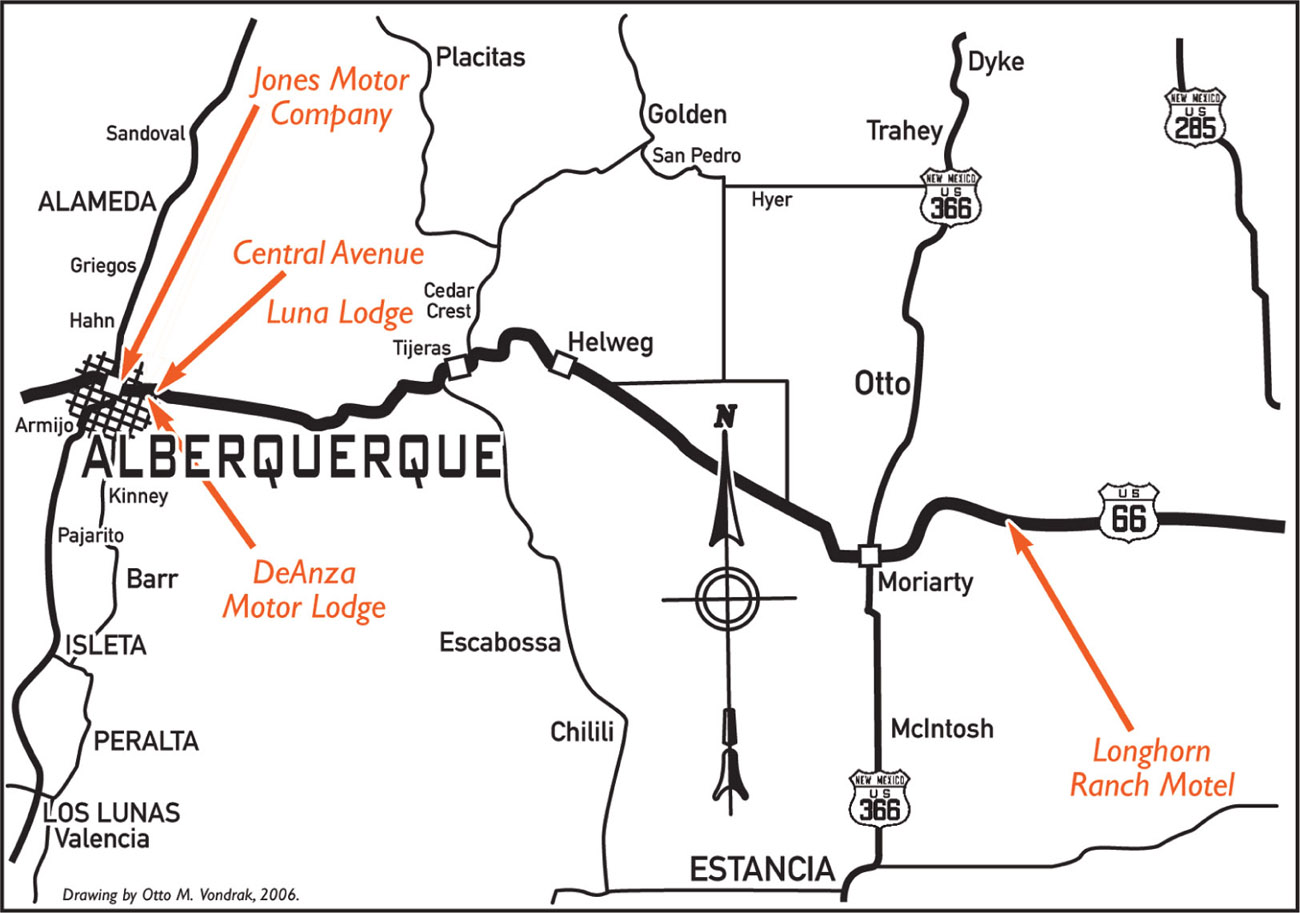

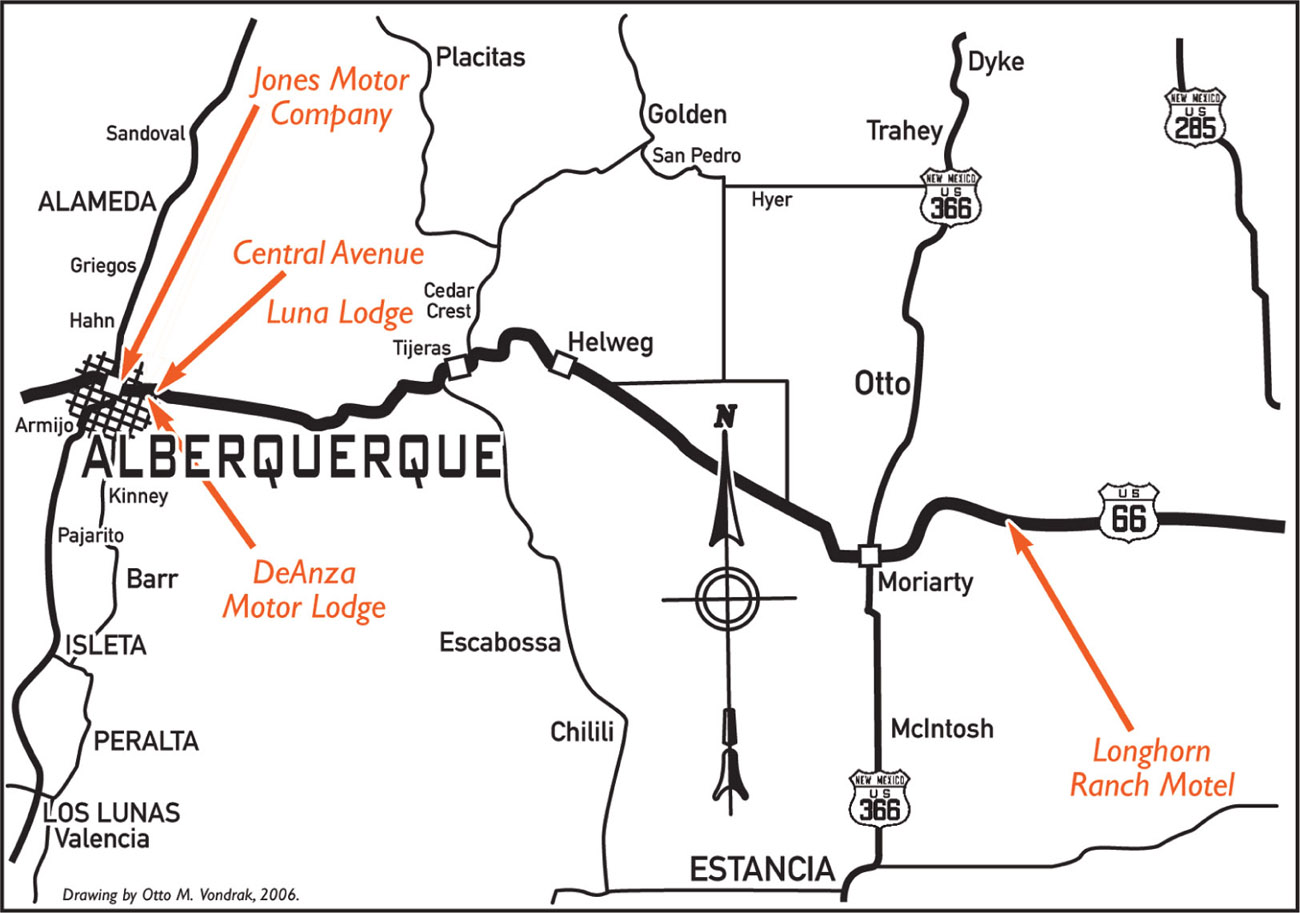

LONGHORN RANCH MOTEL, MORIARTY

c. 1950

Located 70 miles west of Santa Rosa, the Longhorn Ranch Motel was a later addition to the landmark Longhorn Ranch complex. The Longhorn Ranch was built by one-time police officer Captain Eric Erickson, who began his business as a café with a few stools and a single counter. The wide-open desert between Santa Rosa and Albuquerque was barren and often harsh, with few tourist facilities along the way—the perfect scenario for the successes of tourist meccas like Cline’s Corners, the Flying C Ranch, and the Longhorn Ranch. After World War II these outpost businesses expanded like wildfire. The Longhorn Ranch soon became an institution on Route 66, and travelers made it a point to stop there year after year.

At its peak the Longhorn Ranch included a café, garage, service station, curio shop, museum, cocktail lounge, restaurant, and motel. The motel was built on the north side of Highway 66, directly across from the main complex. It featured 15 ranch-style units and an office built to resemble a Western ranch house. The ranch-type setting was the perfect complement to the Old West theme that permeated the main complex across the highway. According to the period postcard, a night’s rest at the Longhorn Ranch Motel was “air cooled by Nature” and offered rubber-foam mattresses and a café just “across the highway with one of the finest Dining Rooms and Cocktail Lounges on Highway 66.”

Nothing but memories remain of the main Longhorn Ranch complex. So thorough was the demolition that one would be hard-pressed to even prove that the landmark roadside stop ever existed. The motel units survive, however, and provide a small taste of what a visit to one of the largest and most glamorous tourist facilities on Route 66 was like. If you decide to stop at the motel, take some time and walk across the old highway to the one-time site of the main Longhorn Ranch complex. If you stand very still, you might hear the sound of the ranch’s famous Concord stagecoach whizzing by as Hondo the driver barks out orders to his team of horses.

c. 1950

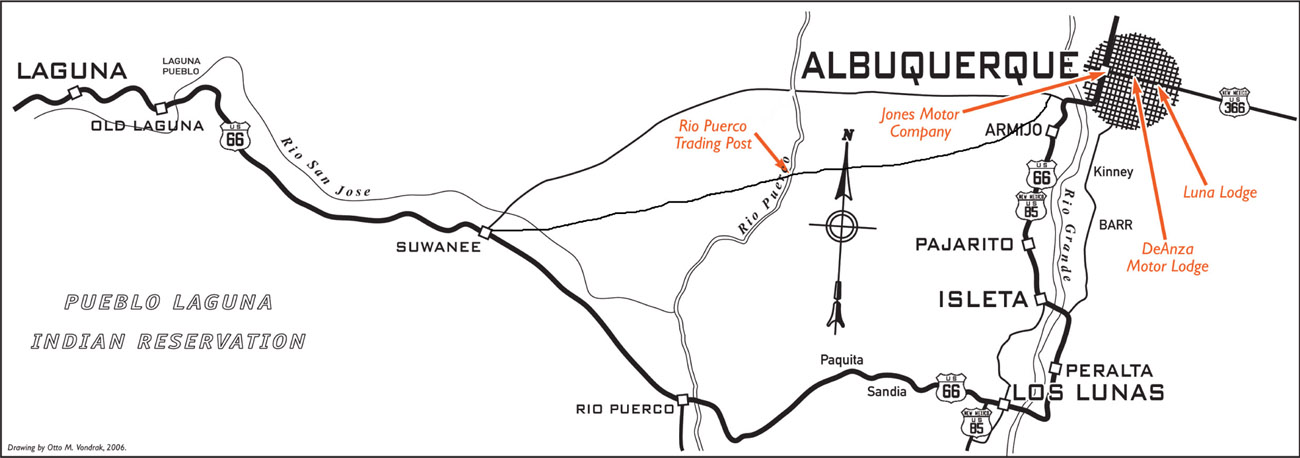

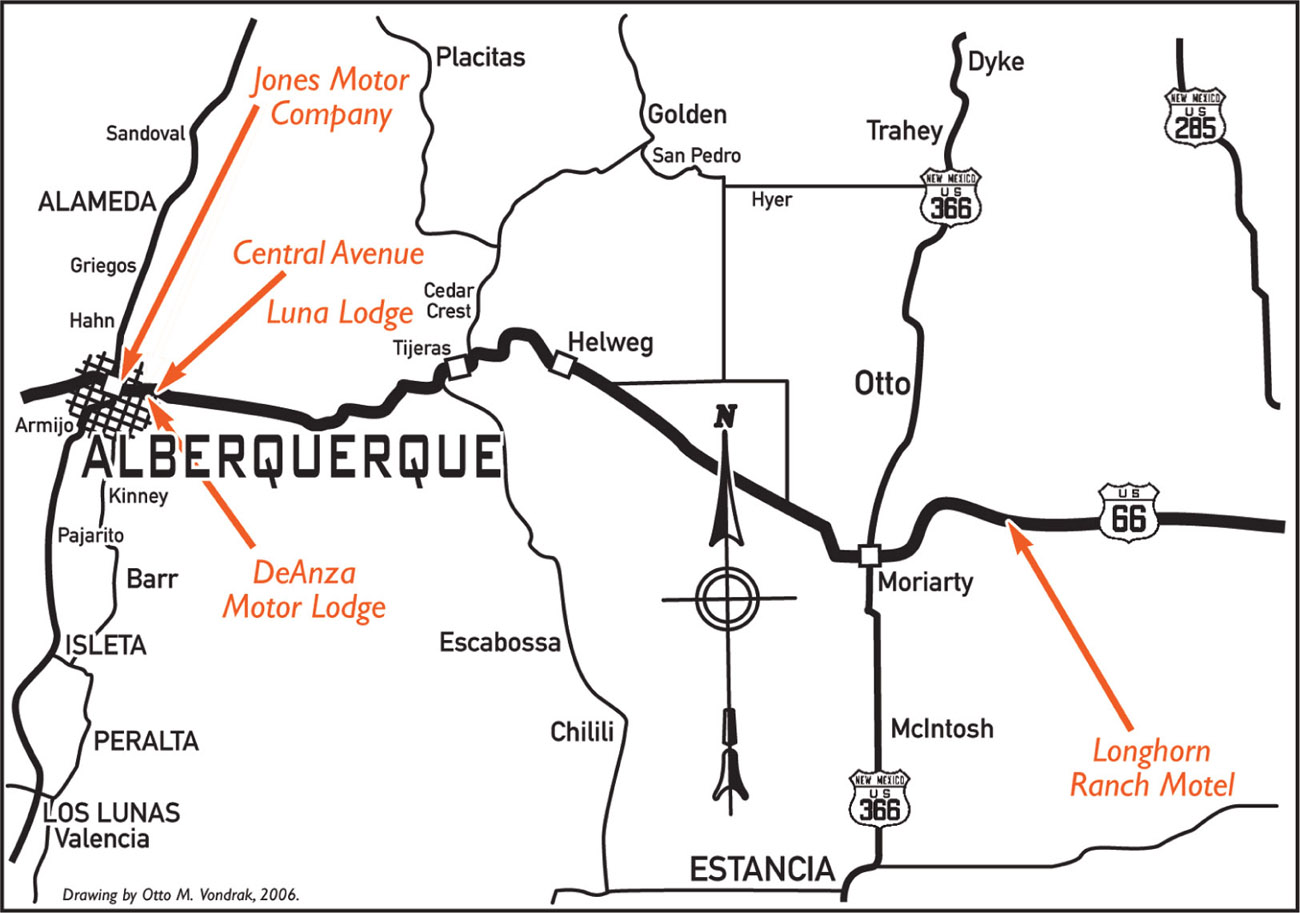

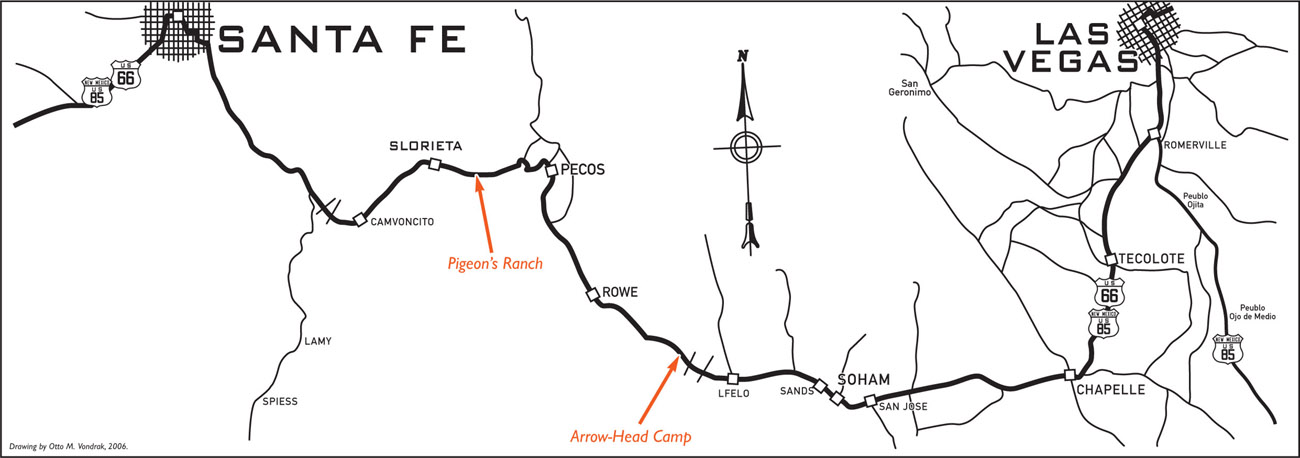

The Spanish villa of Albuquerque was founded in 1706 on the banks of the Rio Grande by Don Francisco y Valdes, the governor of New Mexico. The villa was named for the Duke of Alburquerque, the viceroy of New Spain, and as a result is sometimes referred to as the “Duke City.” (The first r in Alburquerque was eventually dropped.) A vital stop on the El Camino Real or “King’s Highway” connecting Mexico City to Santa Fe, the settlement grew quickly. In 1879 the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway steamed into the area and established New Albuquerque about 1 1/2 miles east of what is now called Old Town. The following year, on April 22, the first rail passengers pulled into the new boomtown.

When Highway 66 was designated in 1926, the road passed through town via Fourth Street, crossed the Barelas Bridge, and continued down Isleta Boulevard. In 1937 the Santa Fe Loop was bypassed, and Route 66 traveled into town via Central Avenue. Prior to realignment in 1935, only 3 tourist camps were located on Central Avenue, while 16 were in operation on Fourth Street. Four years after the realignment, Central Avenue became the focus of tourist facilities. Roadside development flourished, and the number of motels increased to 37.

After World War II and the end of gasoline rationing, the country once again looked to the automobile for vacation travel. By 1955, 98 motels were located on Route 66 within the city limits of Albuquerque. The vintage buildings and motels along the older Fourth Street alignment and the newer Central Avenue alignment represent a virtual museum of popular architectural styles utilized during Route 66’s heyday out West, from Pueblo Revival to Southwest Vernacular to Streamline Moderne. Of the 98 motels operating along Central Avenue during Route 66’s peak years, about 40 that date prior to 1955 still exist today. In 1970 Albuquerque was entirely bypassed by Interstate 40.

c. 1949

In 1949 Route 66 through Albuquerque was called East Central Avenue, and one of the easternmost motels along this stretch was the Luna Lodge. Built in the Southwestern Vernacular style, the Luna Lodge originally consisted of three one-story white stucco buildings arranged in a broken U shape. The office and manager’s residence were located at the front of the westernmost building. Deluxe rooms, which featured carports, were located in the west wing.

The Luna Lodge began operation by offering 18 rooms. By the late 1950s that number grew to 32, when the carports were converted to rooms and a second story was added to the west wing. The manager’s apartment was moved to the front of the new second-story addition, and a porch that was once over the office was filled in to expand the residence. A café called the La Nortenita was also added as a separate structure to the front of the east wing during the 1950s.

Current owner Suresh Patel has owned the property since 1981. He leased the property to another operator from 1992 to 1997, but canceled the lease when that person did not maintain the property to his liking. In 1998 the Luna Lodge was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In 1979 Patel was employed at the New York State Department of Health. During an employee strike he was asked to take a job at a nearby nursing home. It was during this time that he realized how much he enjoyed helping people. Today many of Patel’s guests at the Luna are older military veterans, whom he assists with doctor appointments and transportation to the nearby veterans’ hospital. The monthly rent includes two meals a day at the motel’s café. Buildings’ facades may change and their original uses may become varied and confused, but the giving spirit of the road is alive and well at the Luna Lodge.

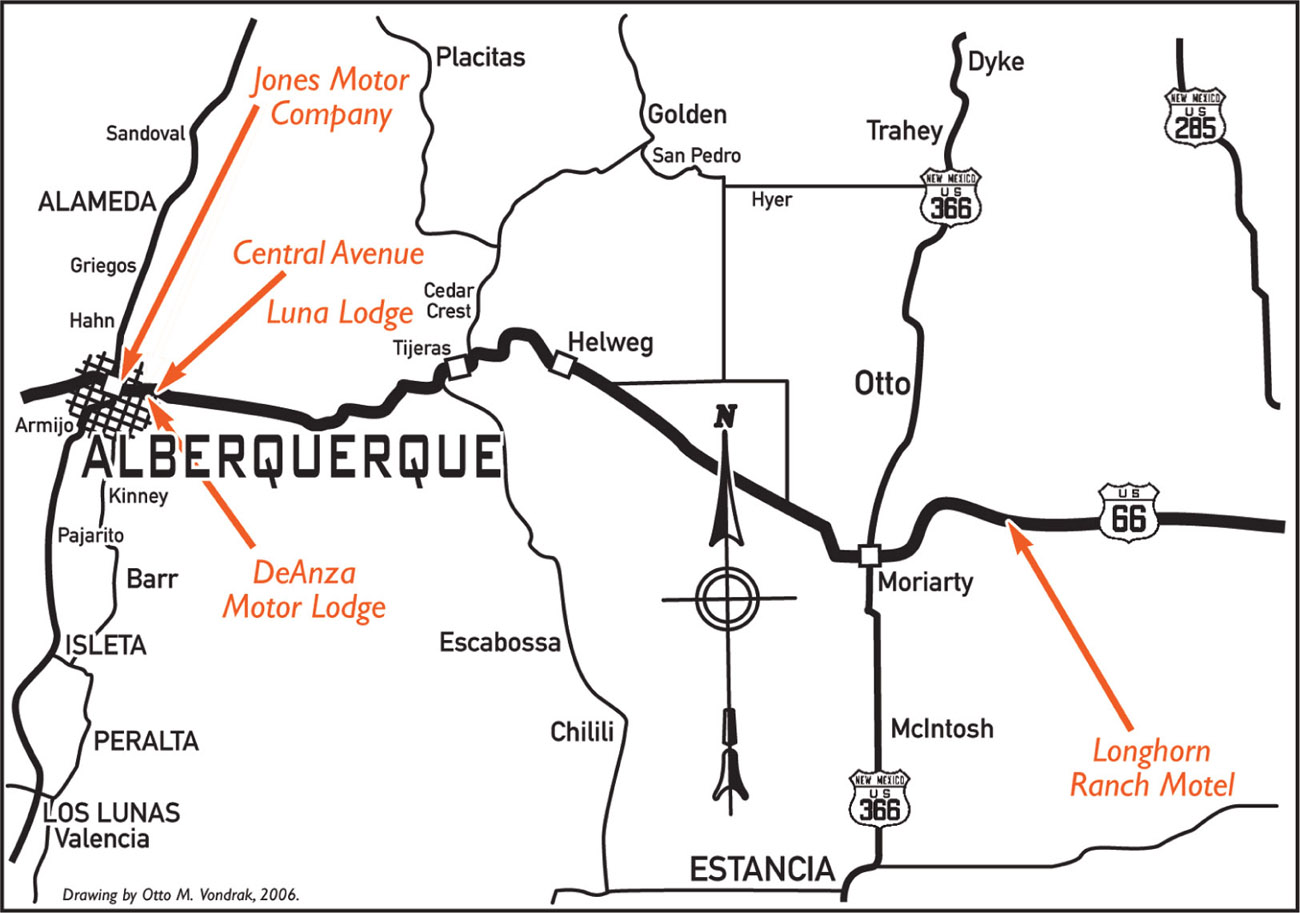

DE ANZA MOTOR LODGE, ALBUQUERQUE

c. 1939

C. G. Wallace and partner S. D. Hambaugh built the 30-unit De Anza Motor Lodge in 1939 in response to the growing number of motorists traveling the 1937 Highway 66 alignment through Albuquerque. The De Anza was named for Spanish Lieutenant Juan Batista de Anza, who rescued the Hopi pueblo from certain starvation and went on to serve as territorial governor of New Mexico from 1778 to 1788.

Unlike the smaller auto courts of the day, the De Anza sits on a full city block (2.5 acres) in the famous Nob Hill–Highland area along East Central Avenue. In 1939 the motel was the largest to date along that section of Central Avenue. The motor lodge was constructed in the popular Spanish–Pueblo Revival style and originally consisted of eight separate stucco buildings. Six one-story buildings formed the classic U-shaped motel of the period. Two two-story buildings, situated one behind the other, formed an island in the middle of the courtyard and served as the office and manager’s residence. Each guest unit had a carport, all of which were eventually converted to more guest units.

In the decade following World War II, Wallace expanded the facility first to 55 units and then to 67 units. By 1957 a coffee shop and pool were added to meet the growing demands of the motoring public. The De Anza was such a popular stopover during its heyday that Wallace would regularly pick up and drop off VIPs at the airport in a shiny pink Cadillac. The De Anza remained listed as an American Automobile Association–approved accommodation until the early 1990s, and Wallace owned the motel until his death in 1993. It was subsequently sold and resold, eventually falling into a mild state of disrepair. Current owner Amir Naggi closed the doors in 2003.

The De Anza Motor Lodge was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on April 30, 2004. A local community redevelopment group is currently working with the City of Albuquerque to preserve and rehabilitate the property. They hope to maintain the integrity of this site, which is closely related to the history of tourism and Indian trade along the once-bustling highway.

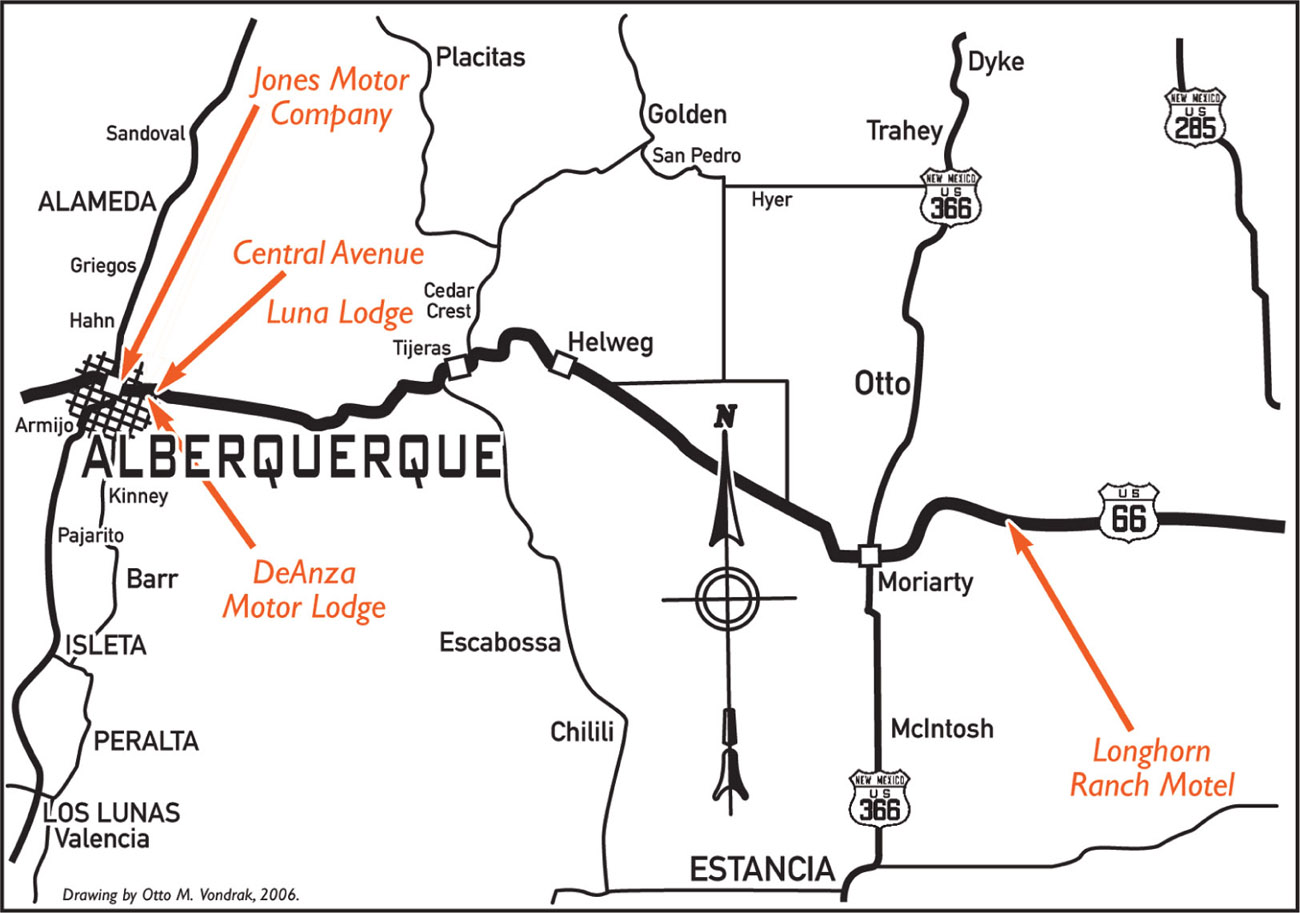

JONES MOTOR COMPANY, ALBUQUERQUE

c. 1943

In 1939 Ralph Jones built the Tom Danahy–designed structure that housed the Jones Motor Company. Hoping to meet the needs of the modern auto owner and traveler, Jones later incorporated a Texaco gas station, creating a Ford dealership and repair center all under one roof. Sitting on a prime location on the east side of town, the auto-repair station was one of the first encountered by westbound travelers on Highway 66.

One of the most notable characteristics of the Streamline Moderne–style building is the stepped tower, which is adorned with ornamental molding that underscores the tower’s shape. The tower was centrally located over the main portion of the building and housed the service station’s restrooms. In 1946 an additional showroom was added to the west side of the building to mirror the original showroom. During the 1950s, a paint and body shop was added in a separate structure to the south of the gas station.

During the Jones Motor Company’s early years, many of the repairs done were on vehicles being driven out West by people fleeing the Dust Bowl. These vehicles were so loaded down with family possessions that access to broken parts was difficult at best. Jones built a long carport along the southern wall of the garage so that cars and trucks could be unloaded in the shade, thus making the vehicles more accessible for repair.

Jones was born on a cattle ranch in Wyoming, where he spent most of his early years. At the end of World War I cattle prices began to plummet, and, desperately needing to supplement his income, Jones took a job selling Model T Fords in Cheyenne. In 1928 he opened his first Ford dealership in Springer, New Mexico. That dealership was eventually moved to the Central Avenue location in Albuquerque and reopened as the Jones Motor Company.

Jones was a huge advocate of Highway 66 and was onetime president of the Route 66 Association, as well as president of the Albuquerque Chamber of Commerce and chairman of the New Mexico State Highway Department during the mid- and late 1940s. The business moved in 1957, and in the subsequent decades the building changed hands several times. The structure housed several businesses, including an army surplus store, a paint and body shop, and a moped dealership. In 1993 the Jones Motor Company building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In 1999 it was purchased by Dennis and Janice Bonfantine and lovingly brought back to life as a brewpub and restaurant called Kelley’s Brewery. Great efforts were made to return the structure to its original design, including the preservation of the vintage garage doors and the addition of two classic Texaco gas pumps out front.

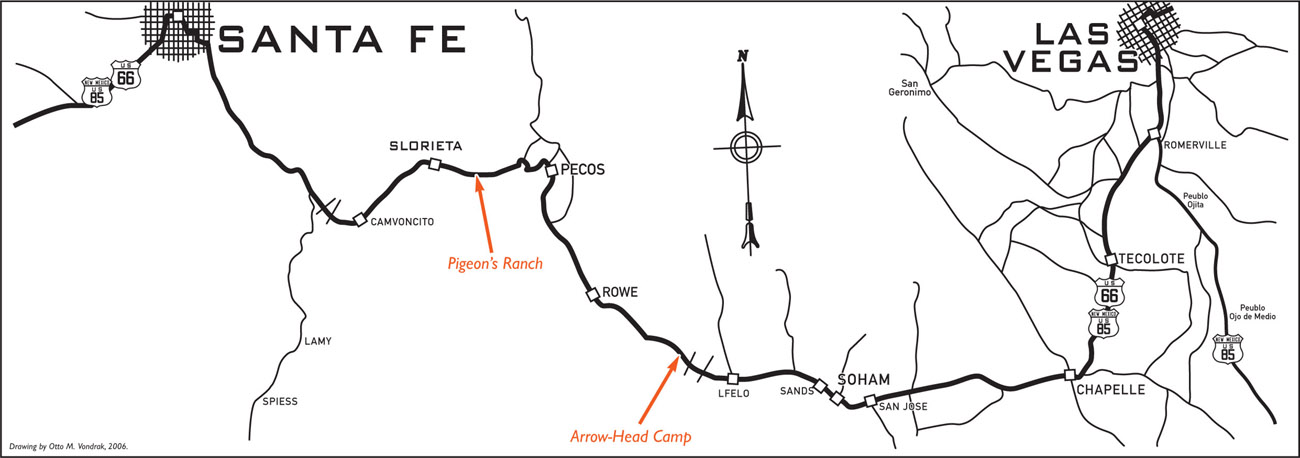

c. 1926

The Arrow-Head Camp was located 22 miles east of Santa Fe on the original alignment of old Highway 66. The road through this area follows the path of the old Santa Fe Trail and is rich with wonderfully historic tales of the Old West. Here the Santa Fe Trail eventually developed into the National Old Trails Highway, Highway 66, and, presently, New Mexico Highway 50. The ancient road in front of the Arrow-Head Camp has seen the gamut of transportation over the last 150 years or so, from horse and wagon to big rigs.

The Arrow-Head Camp was quite a large facility for its time and included a store, cabins, campground, and gas station. During the 1930s the cost for an overnight stay in one of the cabins was 50 cents. Later in the 1940s, the Arrow-Head Camp became known as Arrowhead Lodge and was a popular spot among locals for dinner and dancing. The camp, which comprised mostly log cabin structures, was also a favorite among tourists and sportsmen, situated as it was in a highly wooded, picturesque area.

Route 66’s Santa Fe Loop through Glorieta saw service from November 11, 1926, until January 1937, when a new routing of the road straight from Santa Rosa to Albuquerque shaved off about 90 miles of New Mexico Route 66 roadway. Today the wooded setting that made the camp so scenic is slowly overtaking the log structures. Long ago the Arrow-Head Camp began the process of blending in with the neighboring trees and brush. One day, the camp will complete its journey and totally succumb to its surroundings.

c. 1929

Frenchman Alexander Valle built Pigeon’s Ranch in the early 1820s, around the time that the Santa Fe Trail was being blazed. The name came from the fact that Valle spoke “pigeon English,” or broken English, with a heavy French accent. The ranch became a very important site along the Santa Fe Trail, serving as a stagecoach stop, U.S. post office, and trading post.

On March 28, 1862, Pigeon’s Ranch and the surrounding area, known as Glorieta Pass, was the site of the biggest and bloodiest battle of the Civil War in the Southwest. The adobe building shown here is said to have been used as a field hospital during that battle.

In 1924 Thomas “Tommie” Greer acquired the ranch and turned it into a roadside tourist attraction. Greer was a controversial figure, said to always be looking for a way to turn a buck. The stories go that he lured tourists to stop by offering to fill their jugs with free cold, pure mountain water. That gave him an opportunity to convince them to tour the historic battlefield—for a small fee, of course. Greer also claimed that the well on Pigeon’s Ranch was the oldest in the United States. This claim was unfounded, but it made for good publicity. Bears were also part of this historic roadside attraction’s allure; one particularly ornery black bear constantly harassed tourists and gave Greer trouble.

The bears were gone by the mid-1940s, and in 1966 Glorieta Pass Battlefield, upon which Pigeon’s Ranch sits, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Today, the one remaining historically significant building on Pigeon’s Ranch sits precariously close to NM 50—one wayward vehicle and the irreplaceable structure would be, shall we say, history. NM 50 also slices through the Glorieta Battlefield, making public access to the Civil War site difficult and dangerous. Strong efforts are being made to reroute NM 50 around the battlefield and to restore the area to its Santa Fe Trail and Civil War–era appearance.

c. 1926

The origins of this infamous hill go back more than 400 years, when it was known as the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro and used as a footpath and wagon trail. The U.S. military began to regularly use La Bajada Hill (“the descent” in Spanish) after the Civil War. Soon the wagon road became the main route from Santa Fe to Albuquerque and was used by all types of traffic, including commercial stagecoach lines.

By 1910 adventurous automobile drivers were navigating the old wagon ruts, and in the early 1910s the state highway engineer ordered improvements to the road. Rock retaining walls and a new gravel surface improved the road somewhat. In the 1920s the road, by then known as National Old Trails Highway, was rerouted at the top end of the climb to make travel safer. On November 11, 1926, this portion of the road officially became U.S. Highway 66. From 1926 to 1932 the mere mention of La Bajada Hill struck terror in the hearts and minds of Route 66 motorists. The descent snaked 1.4 miles down the hill at a 6 percent grade and an elevation drop of over 500 feet. This, coupled with hazardous switchbacks, rattled the composure of many motorists. Ascending the hill, you had other worries. In the early days of the automobile fuel tanks were mounted above the carburetors. The ascent was so steep that many automobiles had to travel up the hill in reverse to allow fuel to feed the carburetor.

In 1932 Highway 66 was routed 3 miles east to the same route currently used by Interstate 25. Today, after 50-plus years of erosion and neglect, La Bajada is only traversable with high-clearance four-wheel-drive vehicles.

RIO PUERCO TRADING POST, RIO PUERCO

c. 1940

The Rio Puerco Trading Post was first built in the early 1940s by George Thomas Hill Jr. and his wife, Morene, 19 miles west of Albuquerque, on the south side of the post-1937 realignment of Highway 66. A fire destroyed the original trading post, and the process of rebuilding began in 1946. The updated trading post burned in the 1960s and was replaced by a new enterprise owned by the Bowlin Corporation, the same company that owns the Flying C Ranch site and many other roadside facilities in the Southwest.

Every trading post needed a gimmick, and the Rio Puerco was no exception. A full-sized stuffed polar bear standing in a glass case greeted visitors as they entered the building. One night someone broke into the trading post, broke the glass case, and made off with the bear. It was later found ripped to shreds in the Sandi Mountains outside of Albuquerque.

The Rio Puerco is home to a historically significant bridge that was preserved by the New Mexico State Highway Department. The Parker Bridge, a through truss that spanned 250 feet over the often-treacherous Rio Puerco, was fabricated by the Kansas City Structural Steel Company and completed in 1933. The bridge helped to further the cause for the much-sought-after 1937 realignment of Highway 66 that bypassed Isleta and Los Lunas. The bridge no longer handles vehicle traffic, but can be crossed and explored on foot.