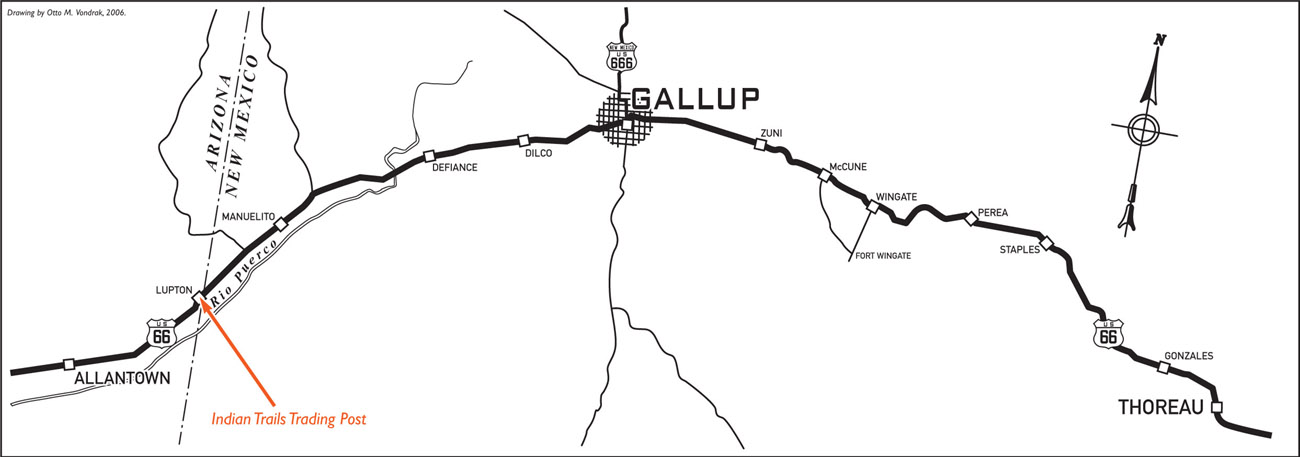

INDIAN TRAILS TRADING POST, LUPTON

c. 1947

During the heyday of Highway 66, service stations, curio shops, and trading posts dotted the western stretch of “America’s Main Street.” Among the most colorful were four establishments located along the state line between New Mexico and Arizona: the State Line Trading Post, Fort Chief Yellowhorse, the Box Canyon Trading Post, and, perhaps the most popular, the Indian Trails Trading Post.

Max and Amelia Ortega established the Indian Trails Trading Post in 1946. In the beginning, local Navajo business was the mainstay, but Max soon expanded the small trading post into a full-service travel stop. As the business grew, the Ortega name became synonymous with fine handcrafted Indian jewelry, and to this day son Armond continues to be one of the largest Indian jewelry dealers in the world. Armond also went on to purchase and revitalize the landmark El Rancho Motel in nearby Gallup, New Mexico.

Today a handful of the old trading posts, including Fort Chief Yellowhorse, remain open, but only memories of the Indian Trails Trading Post remain. In 1965 Interstate 40 was completed from the New Mexico border to a few miles west of Lupton. The land where Indian Trails once sat is now an access road to a rest stop.

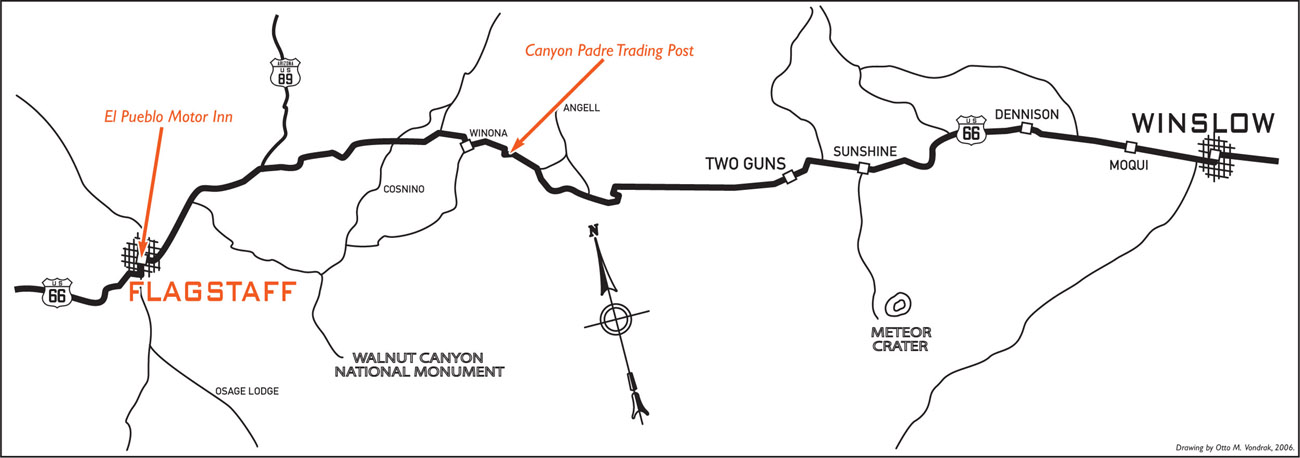

CANYON PADRE TRADING POST, TWIN ARROWS

c. 1949

If you were looking for the quintessential Route 66 tourist stop, the Canyon Padre Trading Post would have to be a front runner in the voting. The Canyon Padre Trading Post was built in the late 1940s and consisted of a store, gas station, and café. The café was a small, 10-stool diner designed by the Valentine Manufacturing Company. Such prefabricated diners were very popular during the 1940s and 1950s and can still be found throughout the United States.

Sometime during the 1950s the Canyon Padre Trading Post became the Twin Arrows Trading Post. To catch the eye of passing motorists, two brightly painted arrows, each 20 feet high, were placed alongside the main building. Made from old telephone poles, the arrows are one of the most frequently photographed sights along all of Highway 66 and are icons of roadside architecture. The Twin Arrows was even featured in a car commercial in the mid-1990s.

A wide variety of goods were available in the trading post, including Navajo rugs, moccasins, and jewelry. When the interstate came through in the late 1960s, an exit to the Twin Arrows saved it from certain demise. The trading post closed in the early 1990s, but in 1995 it was reborn with the help of Spence and Virginia Reidel. Advertised as “The BEST ‘Little’ Stop on I-40,” the post once again featured shelves stocked with souvenirs and pumps dispensing gasoline. Unfortunately, this rebirth did not last, and the business has remained closed since the late 1990s. The property has been severely neglected and is currently in an advanced state of disrepair. The twin arrows that once attracted camera-ready tourists from around the globe now stand beaten and worn, sadly marking the end of an era.

c. 1950

Settlers began arriving in what is now the Flagstaff area around 1876, and sheepherder Thomas Forsythe MacMillan is commonly credited as the area’s first permanent resident. Legend has it that on July 4, 1876, settlers stripped a giant Ponderosa pine and raised an American flag in honor of the nation’s centennial. Subsequently, they named the area “Flag Staff,” and upon the opening of the post office in 1881 the town became known as Flagstaff. A year later the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad rolled into town, securing the town’s future.

Fire destroyed the settlement in 1886 and 1888, but it was quickly rebuilt in both instances. In 1894 Dr. Percival Lowell was attracted to Flagstaff by its clear skies and established the world-famous Lowell Observatory, where in 1930 the planet Pluto was discovered.

Flagstaff sits on the Colorado Plateau at the foot of the San Francisco Peaks and has the honor of being the highest point on all of Route 66. Highway 66 through town is home to many historic structures, including the Museum Club, a well-known roadhouse built in 1931. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1994, the Museum Club continues to attract tourists with its vintage atmosphere.

West on Route 66 past the Museum Club is Flagstaff’s “Motel Row.” Many fine examples of 1930s and 1940s motels line this strip, albeit in varying states of repair. In 1968 Interstate 40 replaced Route 66 through Flagstaff, making it the first city in Arizona to be bypassed. In fact, it would be a full decade before another Arizona Route 66 town was bypassed.

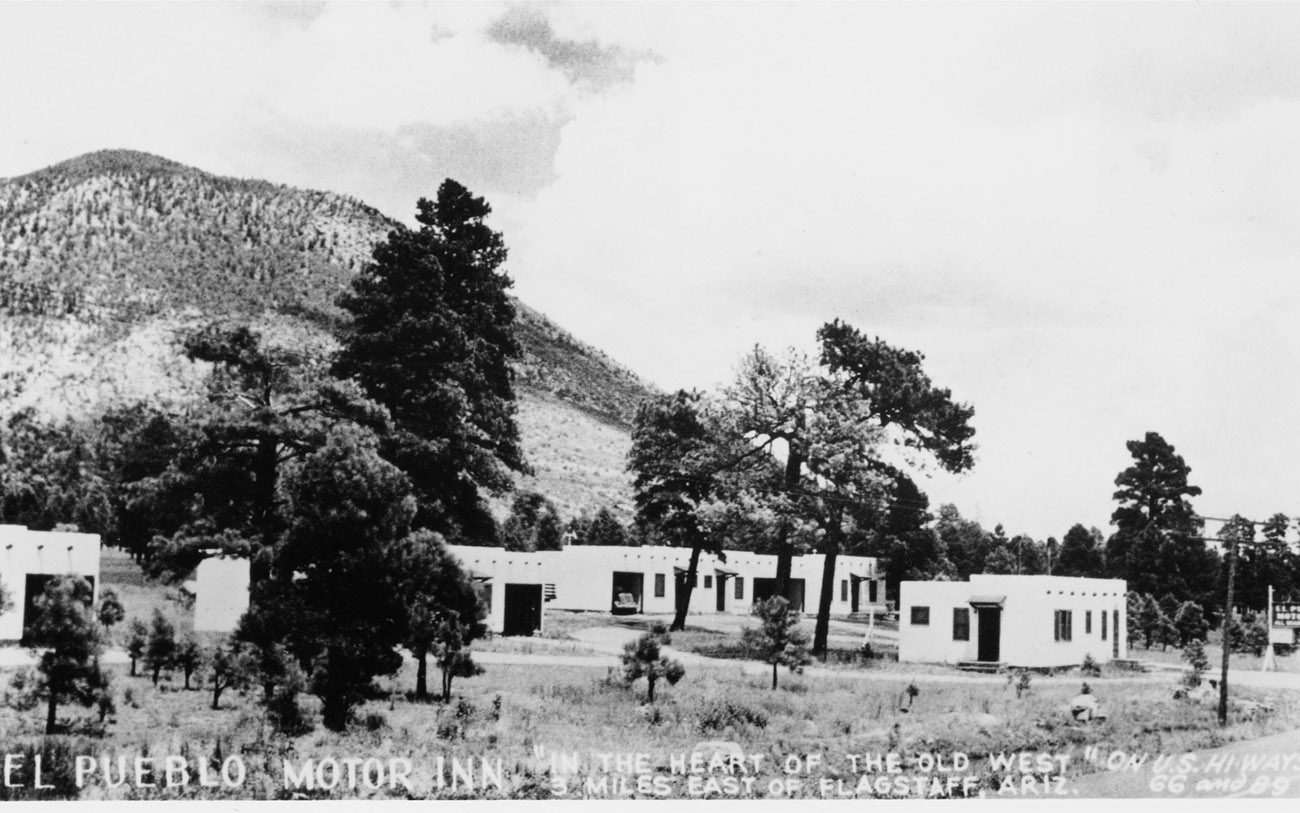

EL PUEBLO MOTOR INN, FLAGSTAFF

c. 1940

E. B. Goble, a local contractor, built the El Pueblo Motor Inn for Philip Johnston in 1936. Born in 1892, Johnston was the son of a Navajo missionary and is best known as the man responsible for developing the Navajo “Code Talkers” program during World War II. Growing up on the reservation as a child, he learned to speak fluent Navajo, and the complex code he developed based on this unwritten language stumped the Japanese throughout the war and saved countless American lives.

The El Pueblo Motor Inn is located 3 miles east of downtown Flagstaff “in the heart of the Old West,” as proclaimed on the back of an advertising postcard. The area was considered “out in the country” when the motel was built. The El Pueblo was quite successful in its day, due in no small part to the fact that it was one of the first auto courts travelers came across when approaching the city from the east. The rooms were set back from the road in a beautiful wooded area dense with pine trees. It didn’t hurt that picturesque mountains formed the backdrop. “Modern comfort in the pines” and “your home away from home” were a couple of the advertising catch phrases Johnston used to attract passing motorists.

Johnston died in 1978, but his El Pueblo Motor Inn still stands among the pines today. Granted, time, the elements, and a string of neglectful owners have taken a toll on the landmark motel. A couple of the rooms continue to be rented on a nightly basis, but most units are currently utilized as monthly rental apartments. Nevertheless, the El Pueblo Motor Inn remains a prime example of the classic 1930sera motor court.

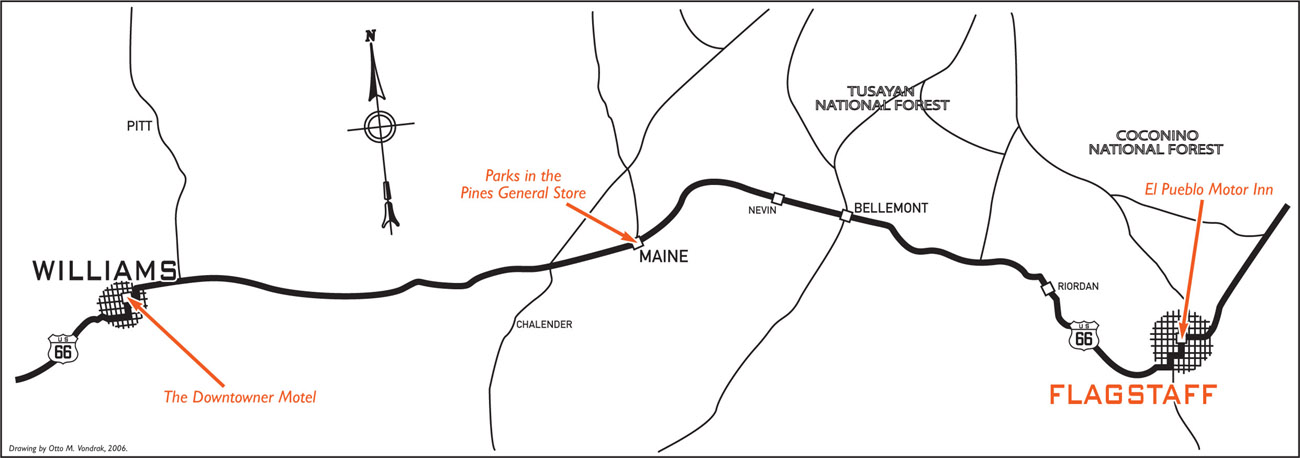

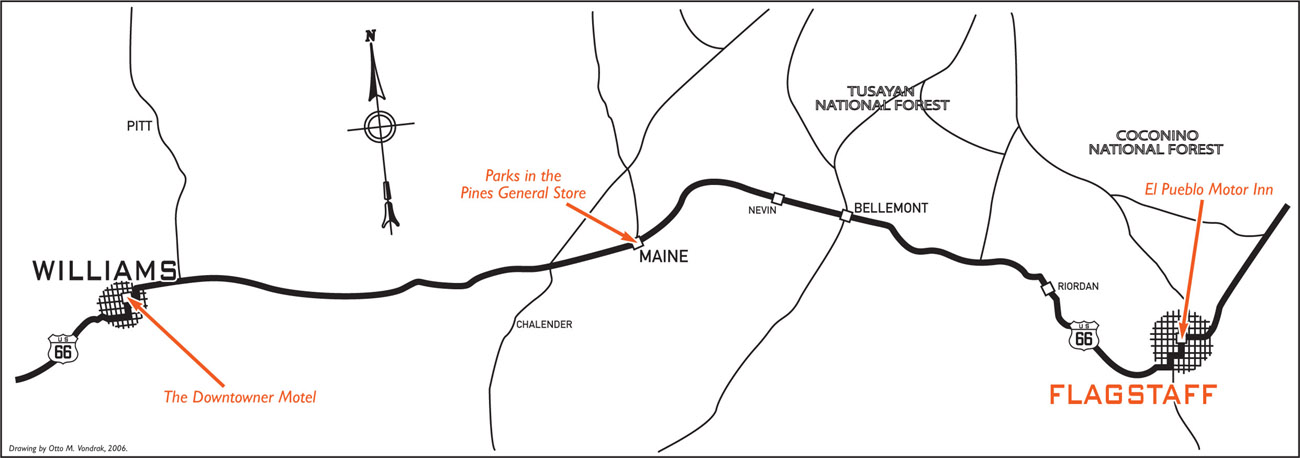

PARKS IN THE PINES GENERAL STORE, PARKS

c. 1929

The town of Parks was originally known as Rhodes, but its name was changed to Maine in 1898 in honor of the famous battleship sunk in Havana Harbor that year. Realizing there was another town in the territory called Maine, the U.S. Postal Service forced the town to find a new name. As it happened, a man by the name of Parks operated a general store and early post office in town, and it was agreed to change the name of the town to Parks in honor of this pioneer shopkeeper.

The original town site was located 2 miles east of its present location, but was moved when the first highway came through. By 1921 the Old Trails Highway was completed and quickly became well traveled as the numbers of automobile tourists grew. Soon there was a need for a good road to the Grand Canyon. Flagstaff and Williams fought over the right to have the new road begin in their town. It was deemed fair to split the difference, and the road was built from Parks. This new road was completed in June 1921.

In November of that same year, Art Anderson and Don McMillan, filling a growing need to serve these masses of tourists, built a general store and gas station at the intersection of the Old Trails Highway and the new road to the Grand Canyon. The original historic building still stands and houses a store and post office. The Flagstaff Chamber of Commerce built the stone columns and sign over the road around the same time as the opening of the store in 1921.

In 1926 the Old Trails Highway was designated Highway 66. In 1928 flamboyant promoter C. C. Pyle (also known as “Cash and Carry” Pyle) organized a footrace to promote the new highway. Billed as “C. C. Pyle’s 1st Annual International Trans-Continental Footrace,” the contest became more affectionately known as the Bunion Derby. The race began March 4 at Ascot Speedway in Los Angeles and followed Highway 66 to Chicago before continuing to Madison Square Garden in New York City. The athletes ran an average of 40 miles a day through municipalities Pyle could convince to pay a fee. Andy Payne, a farm boy from Oklahoma, won, reaching New York on March 26 and claiming the $25,000 prize. Payne (No. 43) is shown at right passing the Parks in the Pines General Store.

Very little has changed about the building since the store’s opening in 1921. The old wood floor strains and creaks with every step, the vintage furnishings hide tales of bygone eras, and the post office inside recalls an earlier time. In 2000 Ron and Millie Gillpatrick purchased the Parks store and continue its fine tradition of serving delicious homemade sandwiches to locals and travelers alike.

THE DOWNTOWNER MOTEL, WILLIAMS

c. 1952

Built during the tourist explosion of the early 1950s, the Downtowner Motel remains a fine example of the modern-styled tourist motels of the era and utilizes the classic U-shaped design. Unfortunately for the owners, the U shape of the motel was doomed from the start. With the massive increase in automobile travel, Williams was overloaded with traffic. Sometime in the mid-1950s, engineers decided to split east and west traffic through town into two one-way streets. Bill Williams Avenue would carry eastbound traffic, while Railroad Avenue would carry westbound travelers.

This split created a logistics problem for the motel and its owner: access to the Downtowner from the west was essentially eliminated. To solve the problem, a portion of the rear of the motel was removed. In its place a driveway was built to allow motel access for westbound traffic.

A part of the Best Western chain and an Automobile Association of America–recommended motel, the Downtowner was a popular stopover. In 1988, Sam Vaidya purchased the motel and initiated some much-needed maintenance. Vaidya vows to preserve the classic look and feel of his 18-unit motel. He understands the importance of Williams and its relationship to Highway 66. Williams has the distinction of being the last town along the entire route to be bypassed, a somber event that took place on October 13, 1984. That same year the Downtown District of Williams became a National Register Historic District, and in 1989 Route 66 through Williams was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

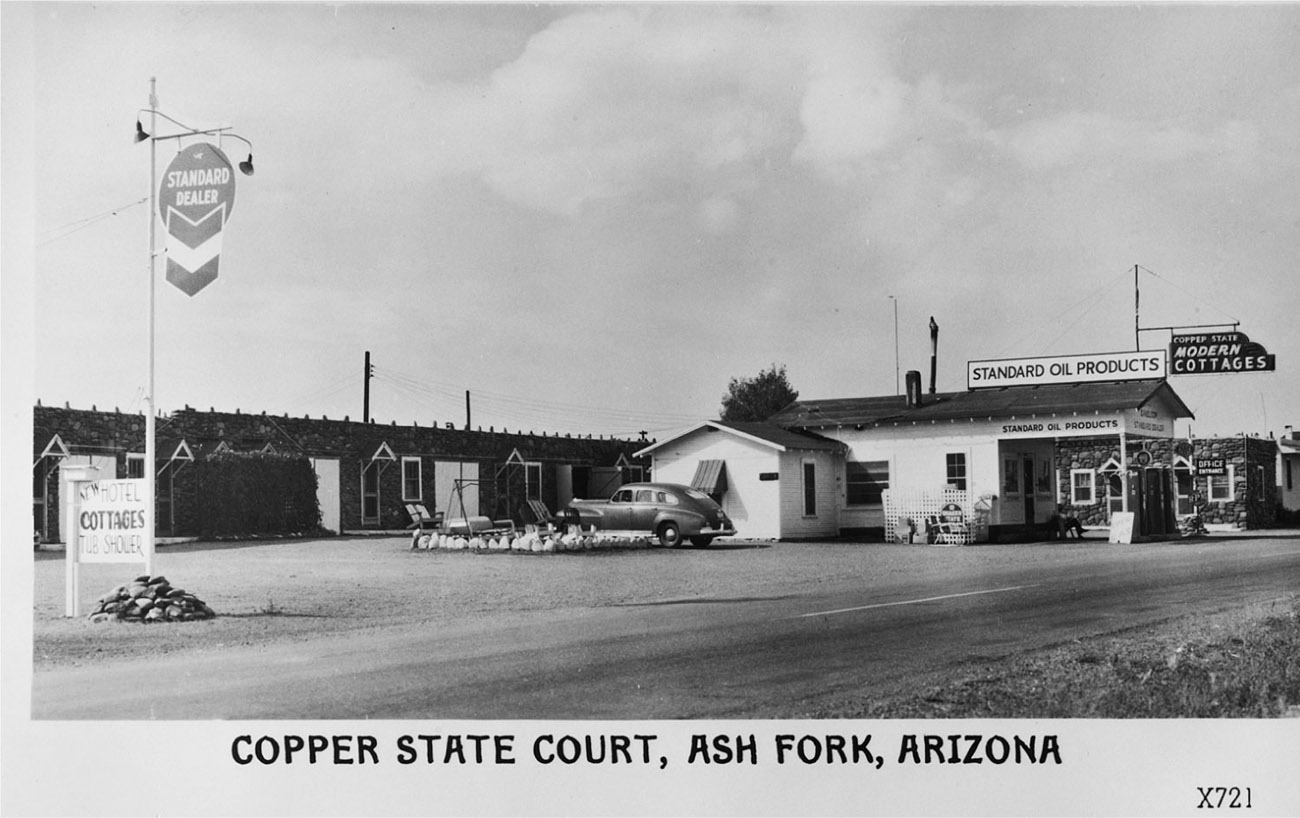

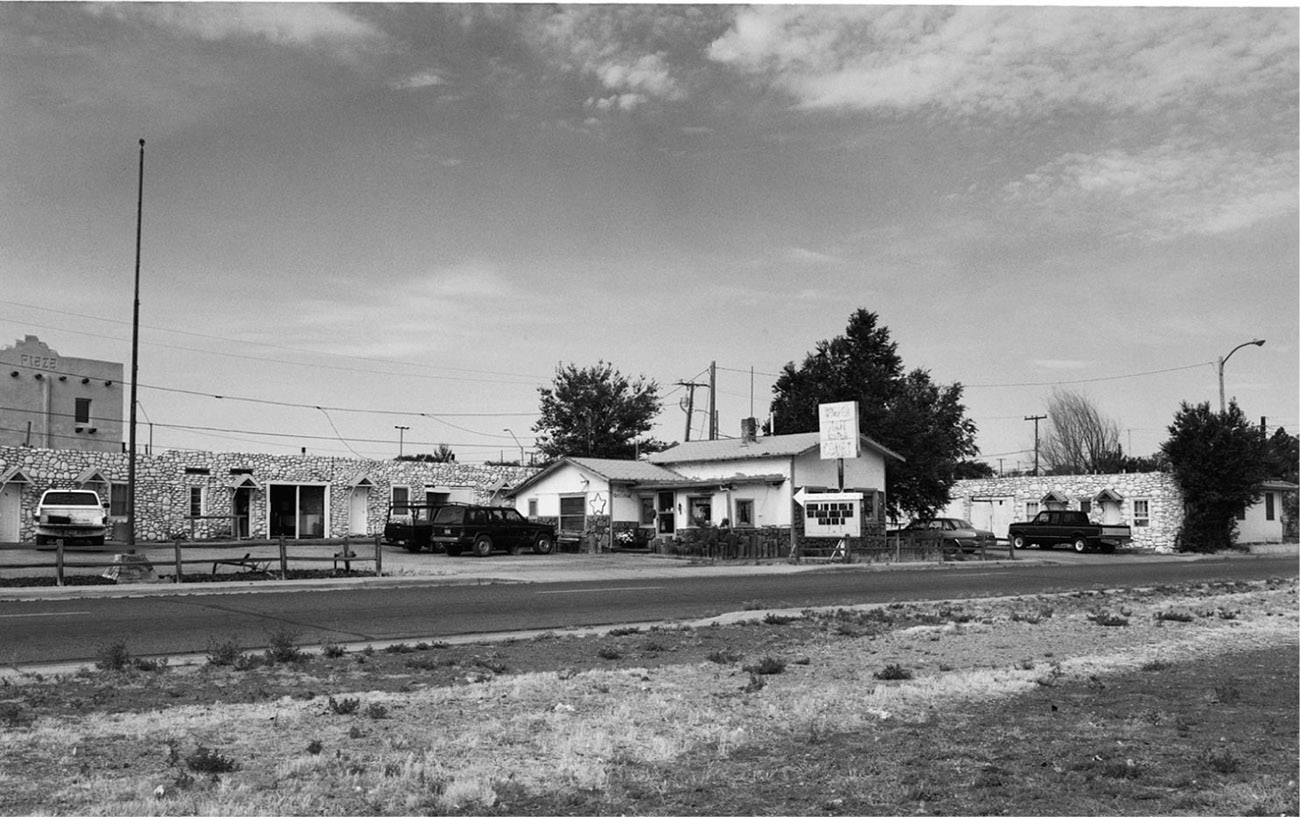

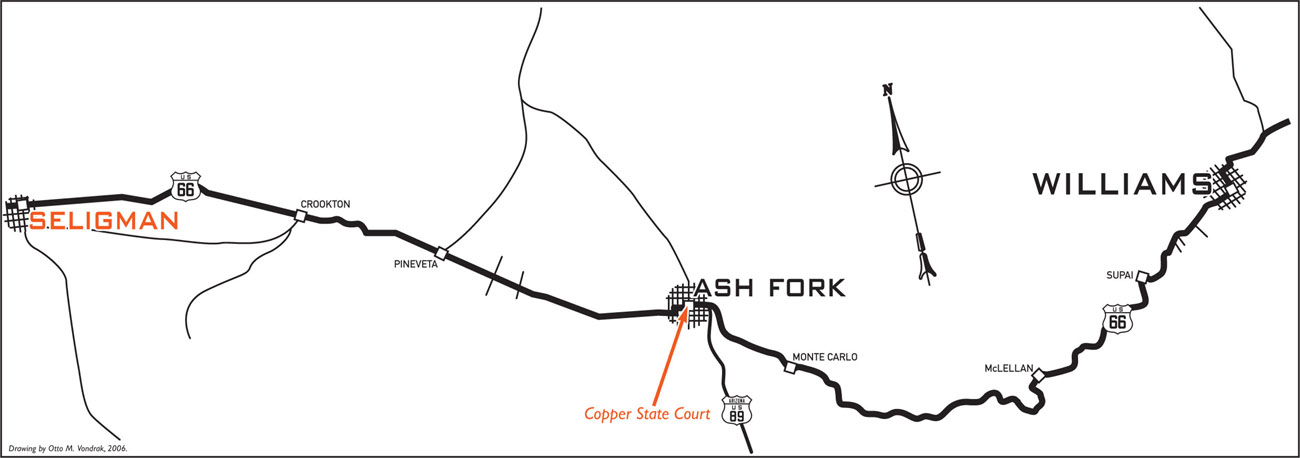

c. 1939

What today is known as the Copper State Court began as a Standard Oil station and general store in 1924, two years before the main street through Ash Fork became Highway 66. Situated on the east side of the once-bustling town, the Copper State Court was the creation of Ezell and Zelma Nelson. Prior to establishing the Copper State, the Nelsons were employed at the Harvey House in Kingman, Arizona. Seeking a better life for themselves, they set out to build a business of their own. The Nelsons realized their vision in 1928, when they finished adding a 12-cottage motel to the gas station and general store. The business became known as the Copper State Modern Cottages.

The cottages are set up in the classic L shape, with the office located on the west end. Each cottage was meticulously built using white river rock held together with black mortar. The natural stone survived until it was deemed necessary to do something to attract the attention of passing motorists, at which time the exteriors of the units were painted a stark white. Not only was this gambit successful, it also gave the impression of cleanliness, which of course remains a very important virtue to potential guests.

Hardwood floors were featured throughout each of the units. Eventually the hardwood was removed from the bathrooms and replaced with concrete. Other than that, all of the original hardwood remains intact. Room size varies from unit to unit but averages 12x14 feet.

Garages were situated alongside each unit, as was the norm during that era. In fact, one of the more interesting facts about this Highway 66 icon involves these garages. When the Copper State was originally built, horse travel was still a viable mode of transportation, especially in the West, and the original garages came equipped with horse railings along the inside walls. Whether used as stalls or garages, these covered spaces protected the chosen mode of transportation from the often-harsh elements. The garages have long been enclosed and now serve as storage sheds for long-term residents.

The name of the motel was eventually changed sometime during the early 1940s to the Copper State Court to keep up with the times. During the mid-1950s the gas station was remodeled to include a living space and office. Sometime during the 1960s the station closed, the gas pumps and tanks were removed, and the canopy was razed.

Both the Copper State Court and Ash Fork have had their ups and downs. During World War II, regular stops by troop trains brought thousands of servicemen and -women through town, many of whom left a portion of their hard-earned pay in one of the local cafés or bars. The 1940s and the following years brought a deluge of vacation travelers, and the Copper State and Ash Fork hit their peak. Thousands of cars per day traveled Route 66 through town, heading west to California. Ash Fork was a beehive of activity. Sometime during the 1950s, however, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway moved its main line 10 miles north of town, a move that had a profoundly negative impact on the local economy. Then, in the early 1970s, a ferocious fire destroyed many of the main-street businesses. The final insult occurred in 1979 when the interstate bypassed Ash Fork, leaving many businesses, including the Copper State Court, in the proverbial dust.

Current owners George and Brenda Bannister purchased the Copper State Court in October 1989 and have kept intact much of the original charm of this classic vintage motor court. The only major overhaul, according to George, was the modernization of the ancient plumbing and fixtures. He is quick to point out that the Copper State was one of the first motels in the entire region to have indoor restrooms, a feature that made the motel an extremely attractive destination for business travelers and honeymooners. He fondly remembers one morning watching a gentleman drive past the motel over a dozen times. Every time the man got close he slowed down the car but never stopped. Finally, after about a half hour or so, he stopped, got out of his car, and closely examined the grounds and the doors to every room. It turned out the man and his wife spent their honeymoon night at the Copper State Court more than 65 years earlier. “This happens on a regular basis,” says George.

George is proud to report that Route 66 travelers from all over the world have stayed at the Copper State. Seven of the 12 rooms are currently rented out on a weekly or monthly basis. Room No. 4 is the only unit equipped with a kitchenette and the only room that features a separate bedroom. The remaining five units are available for overnight stays.

c. 1951

In the mid-1800s the area around what is today Seligman was known as Mint Valley. Settlers and pioneers traversed through the region via the Beale Wagon Road. In 1886 residents of nearby Prescott were convinced to finance a rail line called the Prescott & Arizona Central Railroad, which would connect Prescott with the Atlantic & Pacific main line via Mint Valley. With that connection, Mint Valley became known as Prescott Junction. The Prescott & Arizona Central soon went out of business, the line from Prescott Junction to Prescott was torn up, and Prescott Junction’s name was changed to Seligman. It was named for two brothers who owned stock in the Atlantic & Pacific and were partners in the Aztec Land and Cattle Company.

The Atlantic & Pacific became the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad, or, more simply, the Santa Fe, in the late 1890s. In 1897 the Santa Fe moved its western terminus and roundhouse from Williams to Seligman, giving a huge boost to Seligman’s economy. In 1905 the Santa Fe built a Harvey House dubbed El Havasu. When Highway 66 was designated in 1926, Seligman became an important stop for travelers, and once again the town reaped the benefits. Auto travel was on the rise and rail travel suffered for it. In 1954 a lack of passenger rail travel forced the Santa Fe to close the El Havasu. The building still stands and is used as office space by the BNSF Railway.

On June 29, 1956, President Dwight Eisenhower signed the Federal Highway Act, marking the beginning of the Interstate Highway System and the beginning of the end for Highway 66. On September 22, 1978, Interstate 40 bypassed Seligman. Route 66, the main street through town, suddenly fell quiet, and businesses quickly felt the effects.

Down, but not defeated, the town rallied around brothers Angel and Juan Delgadillo, who, beginning in 1985, led the current Route 66 revival and sparked new interest in the historic highway. Preaching the significance of the fabled highway to anyone who would listen, the Delgadillos were instrumental in getting the road redesignated as Historic U.S. 66. They are credited with the resurgence and increased popularity that the old road currently enjoys. Today Seligman reaps the rewards of their hard work and dedication as one of the more popular stops among tourists traveling Historic 66. A visit to the Snow Cap Drive-In, built by Juan and owned by the Delgadillo family, is a must. The drive-in is one of the most photographed and talked-about spots on all of Route 66.

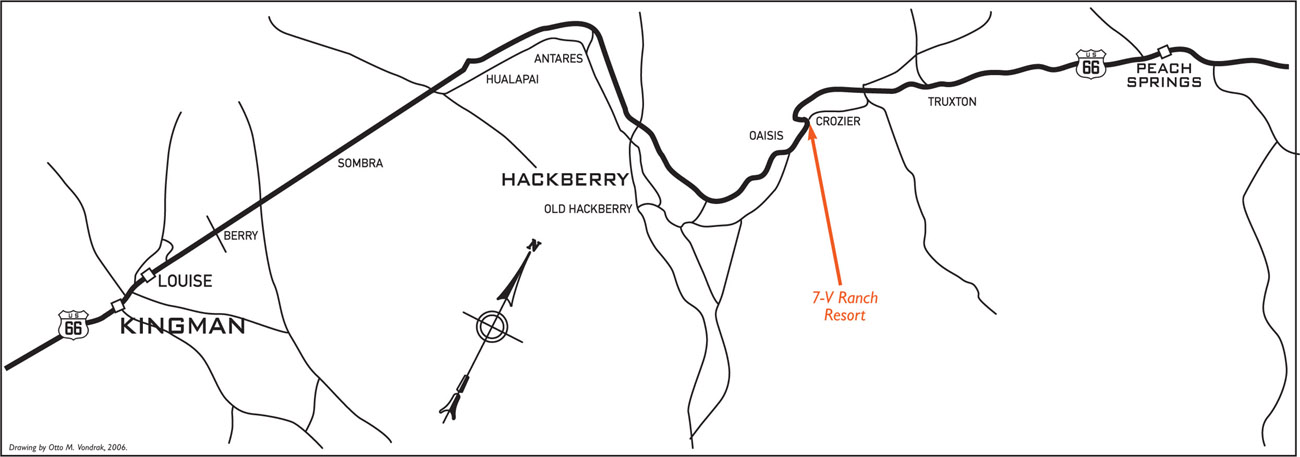

c. 1935

Ed Carrow began building his multipurpose ranch well before the designation of Highway 66 in 1926. Along with his six brothers, Carrow built up the business that originally consisted of a slaughterhouse and dairy to eventually include a restaurant, garage, gas station, and auto court. The 1924 restaurant on the Old Beale Road was completed from stones that he salvaged from nearby abandoned railroad bridges. The restaurant was a great success, and bus lines made the 7-V Ranch a regular meal stop. A swimming pool was later added, much to the delight of scorched bus passengers, who cooled off with a quick dip before resuming their trips.

Tourist traffic picked up after the designation of Highway 66, and Carrow built a row of eight small cabins to accommodate overnight guests. The cabins were built with two guest units in each building and sat alongside Crozier Creek, which ran through the property. Heavy rains caused the creek to flood in 1939, destroying the garage and gas station. The flood also damaged a portion of the restaurant and some of the cabins. Route 66 was soon rerouted to higher ground to avoid another disaster, thus bypassing the ranch. A few remnants of the 7-V Ranch Resort remain, including the row of cabins alongside Crozier Creek.

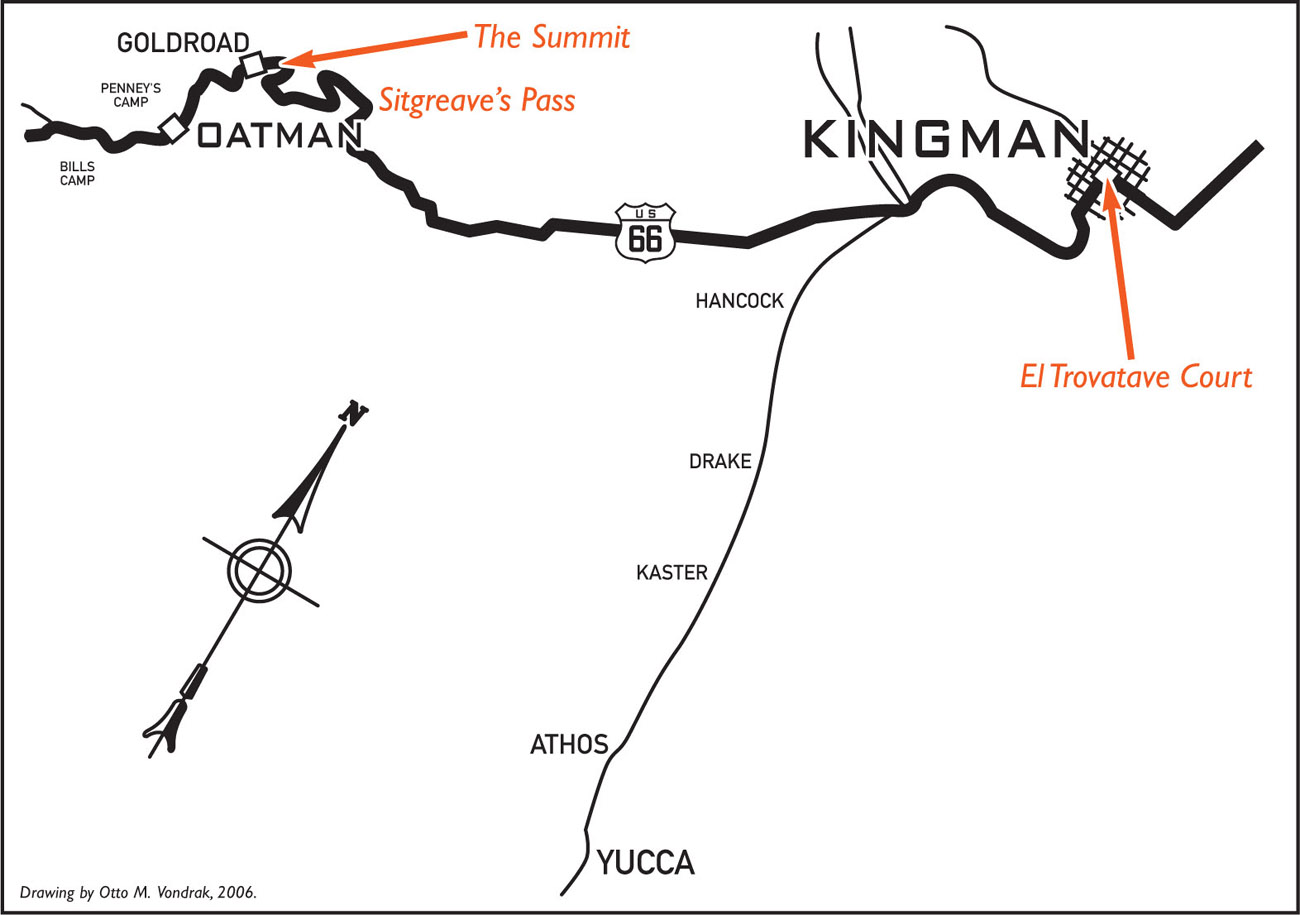

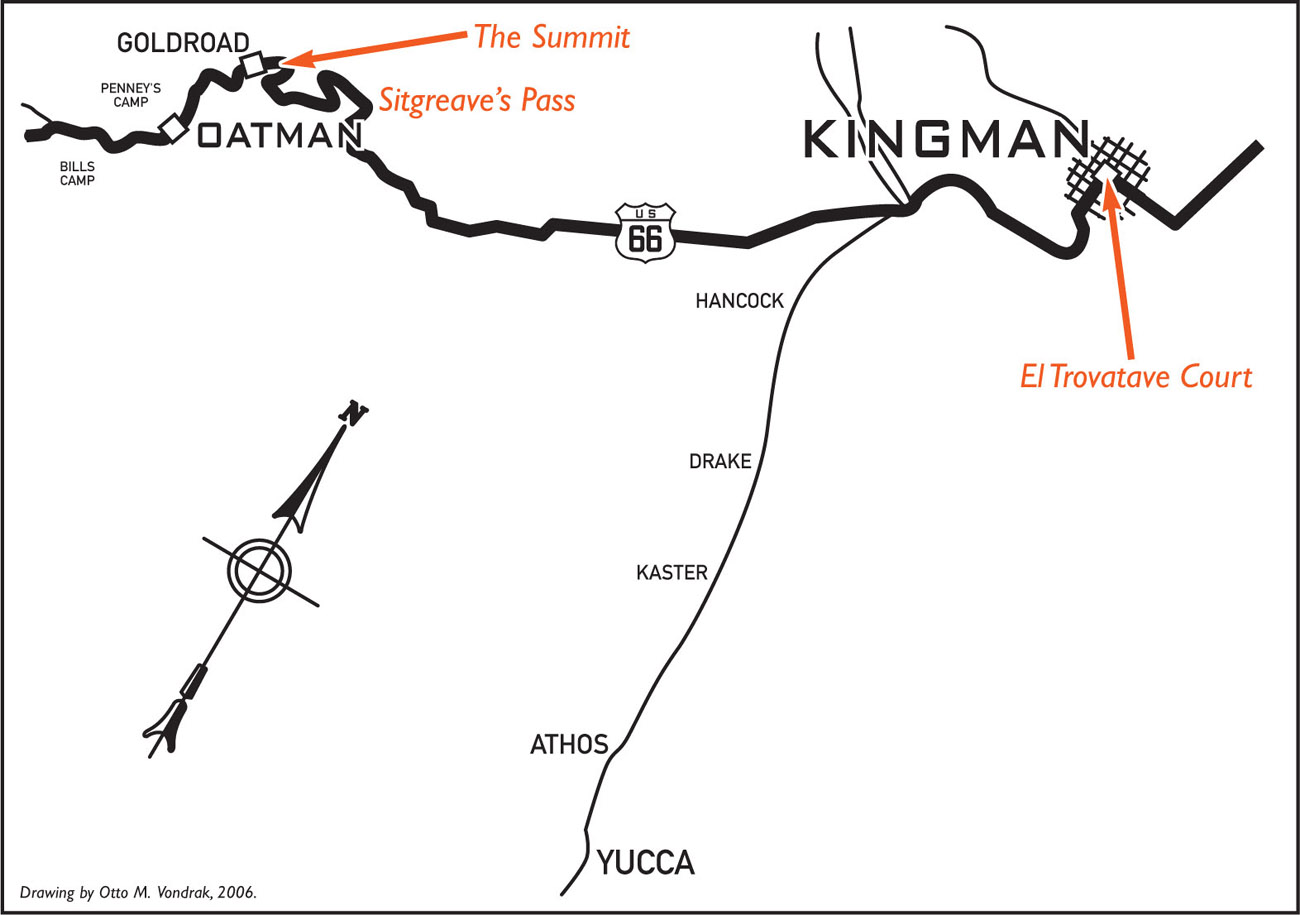

c. 1960

Since the early 1900s Kingman has served and flourished as an important transportation hub for the western United States. But when Kingman was chosen as a Highway 66 city, the tourist industry began to blossom in earnest, and dozens of auto courts sprang up along Kingman’s roadside.

In the late 1930s John F. Miller purchased the future site of the El Trovatore. Miller was no stranger to the hotel business. He built his first in Las Vegas on the corner of Main and Freemont—a two-story structure later known as the Golden Gate Casino—and in December 1939 the El Trovatore received its first guests. The motel consisted of 30 units back in 1939, and overnight rates started at $3 a night. The El Trovatore became a very popular stop in Kingman, and to keep up with demand Miller added another 24 rooms. The bathrooms used hand-cut tiles in a variety of colors to add a very elegant look to each room. A cocktail lounge and dining room were also part of the facility. The interiors of both were quite unusual, featuring walls lined with large rocks to give the impression of being inside a stone structure.

The interstate bypassed Kingman in 1953, and the El Trovatore subsequently went through a succession of ownership changes. The motel began to slowly deteriorate both in appearance and reputation. In May 2005 Karen M. Kreiger purchased the El Trovatore with plans to revitalize the motel and repair its somewhat seedy reputation. The motel is currently going through a complete renovation; the first phase was completed in 2005 and the second phase, mainly interior renovation, should be completed by April 2006. All rooms will be completely redone by then with new furniture and carpet. Although Kreiger contemplated whether to reopen the El Trovatore as an apartment complex, a motel, or a combination of both, she is leaning toward apartments because of the constant upkeep required for a motel of this size. The rear building is currently in use as monthly rentals.

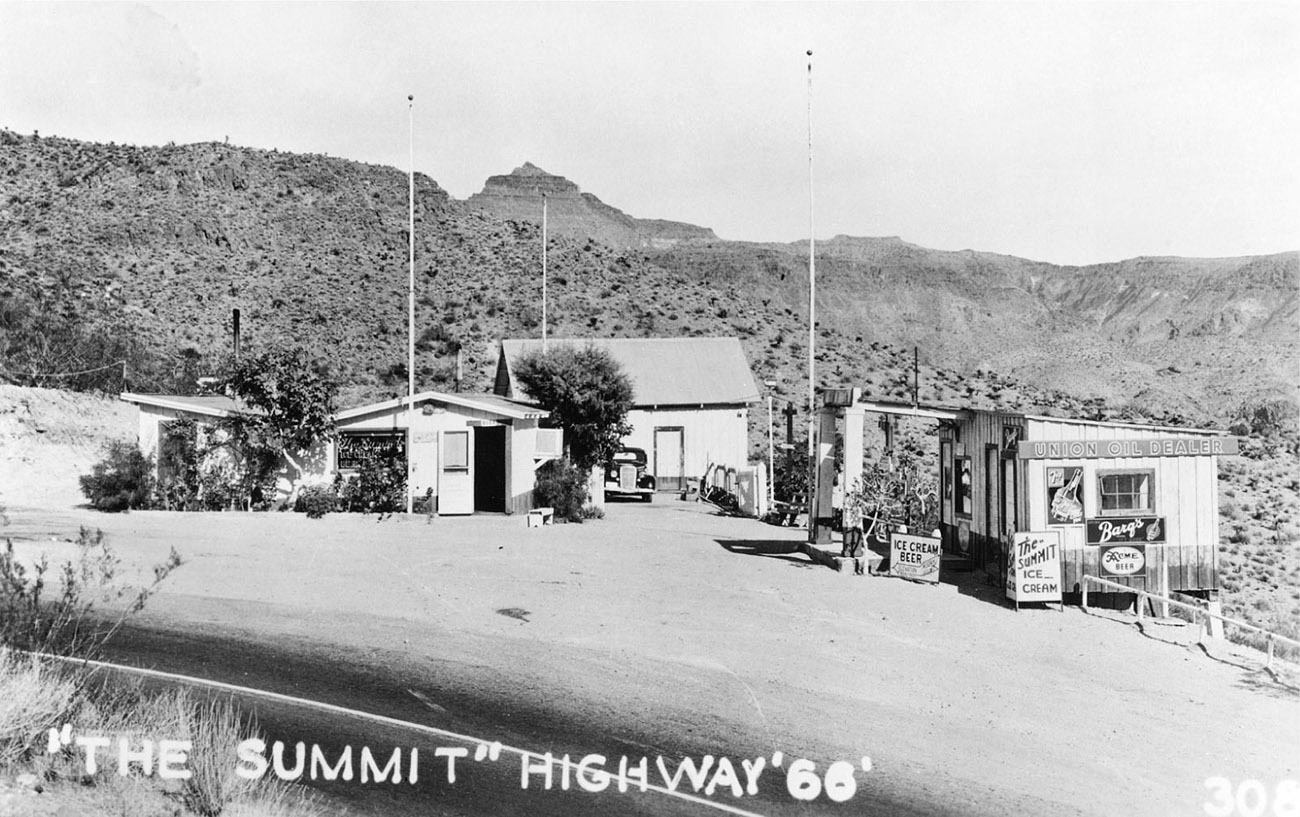

c. 1940

As it scales the foreboding Black Mountains, Highway 66 rises to a peak of 3,550 feet above sea level between Kingman and Oatman. The pass through this mountain range was named for Captain Lorenzo Sitgreaves, who in 1851was sent on a mission to assess the navigability of the Zuni and Colorado rivers for use in a possible confrontation with the Mormon settlement in Utah. Around 1861 Sitgreaves Pass was the site of an immigrant massacre by the Hualapi and Mohave Indians.

The Summit filling station and ice cream parlor was located 24 miles west of Kingman, on the first routing of Route 66 through the Black Mountains at the summit of Sitgreaves Pass. Imagine inching up the pass in your automobile. The car has no air conditioning, and as hot as it is outside, it is hotter in the car. The gas gauge is reading low. You should have listened to your wife and filled up earlier. The kids are complaining every step of the way. Your throats are parched. As the car struggles on, beads of sweat fall from your forehead, clouding your vision. As you reach the summit, you are just able to make out a sign ahead on the right. Does that sign say “Ice Cream”? No, it couldn’t be. Ice cream and beer!? The kids see the ice cream sign and demand you pull over. Of course you were going to anyway. This scene probably occurred several times a day on this section of Route 66. The Summit must have been a strange and wonderful sight after taking on the perils of the pass.

Today memories of relieved parents and children’s faces dripping with ice cream, as well as a few crumbling foundations, are all that are left of the Summit, which burned to the ground in 1967.

c. 1941

Topock began in 1883 as a small settlement populated by bridge builders and railroad employees who were constructing the first bridge across this section of the Colorado River. The area was chosen for the crossing because of the narrow width of the river at this point. When a post office was established in 1906, the settlement was originally called Acme, but was later changed to Topock, a Native American word for “water crossing.”

There is no real town of Topock, and to give you an idea of how little there is here, the Topock post office is actually located in the nearby community of Golden Shores. The Needles Ferry was established here in 1890 and was the only way to cross the river if you were not traveling by rail. The ferry continued to carry travelers across the Colorado until a flood destroyed the facility in 1914. A Guidebook to Highway 66 (1946) states that Topock’s facilities at that time included “gas, grocery, a few cabins and a garage for light repairs; limited facilities.” Nothing remains of these “limited facilities,” although there is a marina on the shores of the Colorado River.