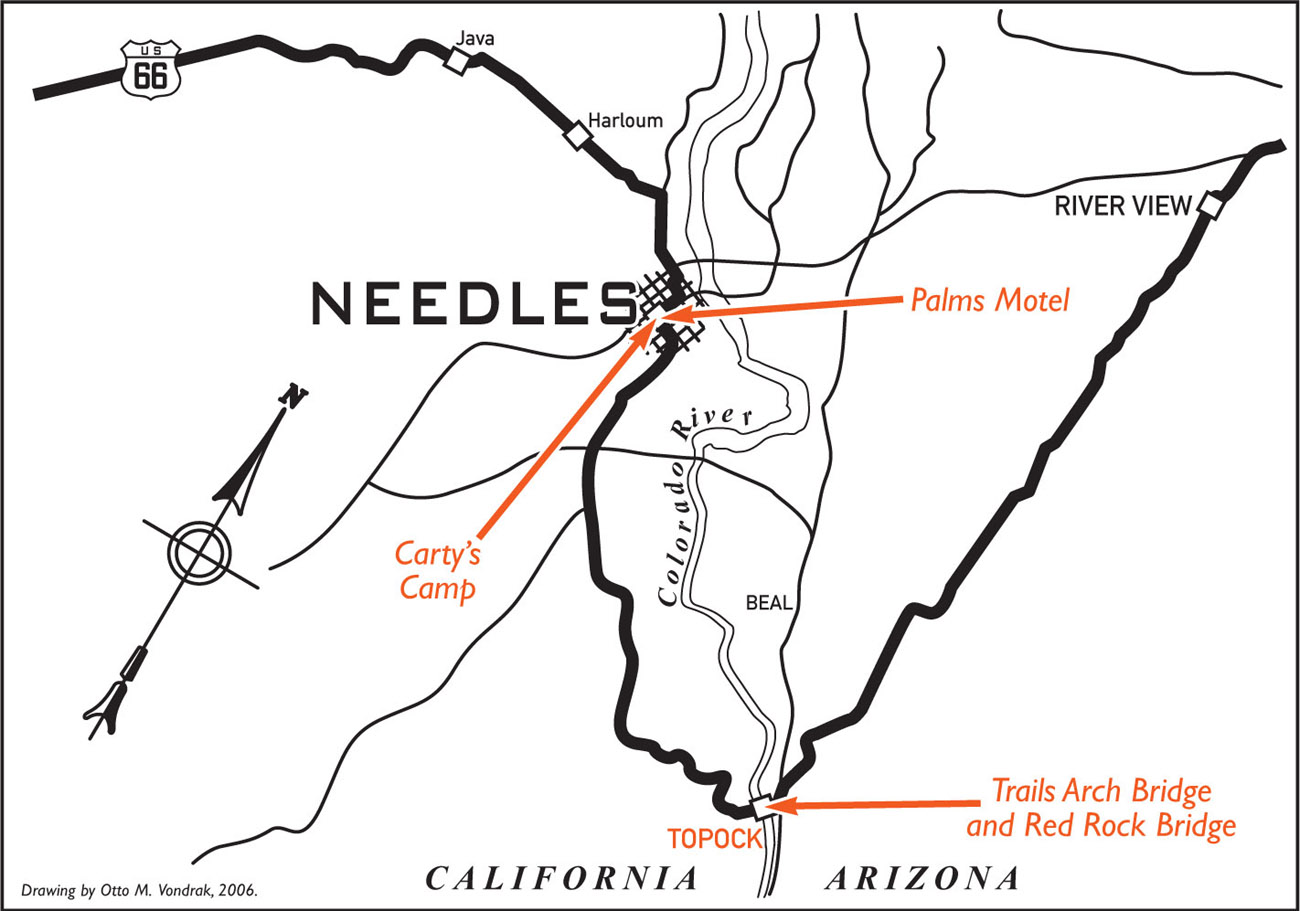

TRAILS ARCH BRIDGE AND RED ROCK BRIDGE

c. 1933

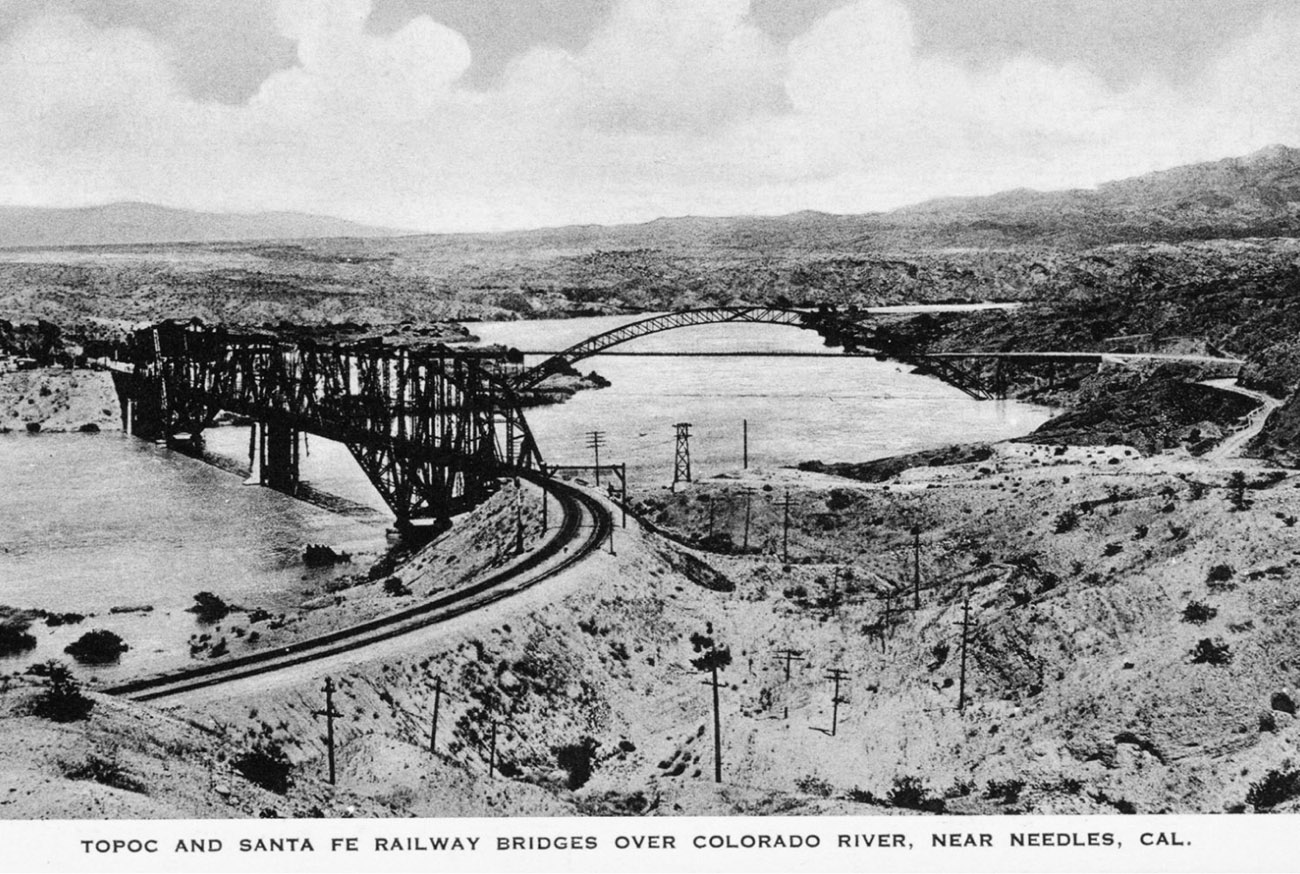

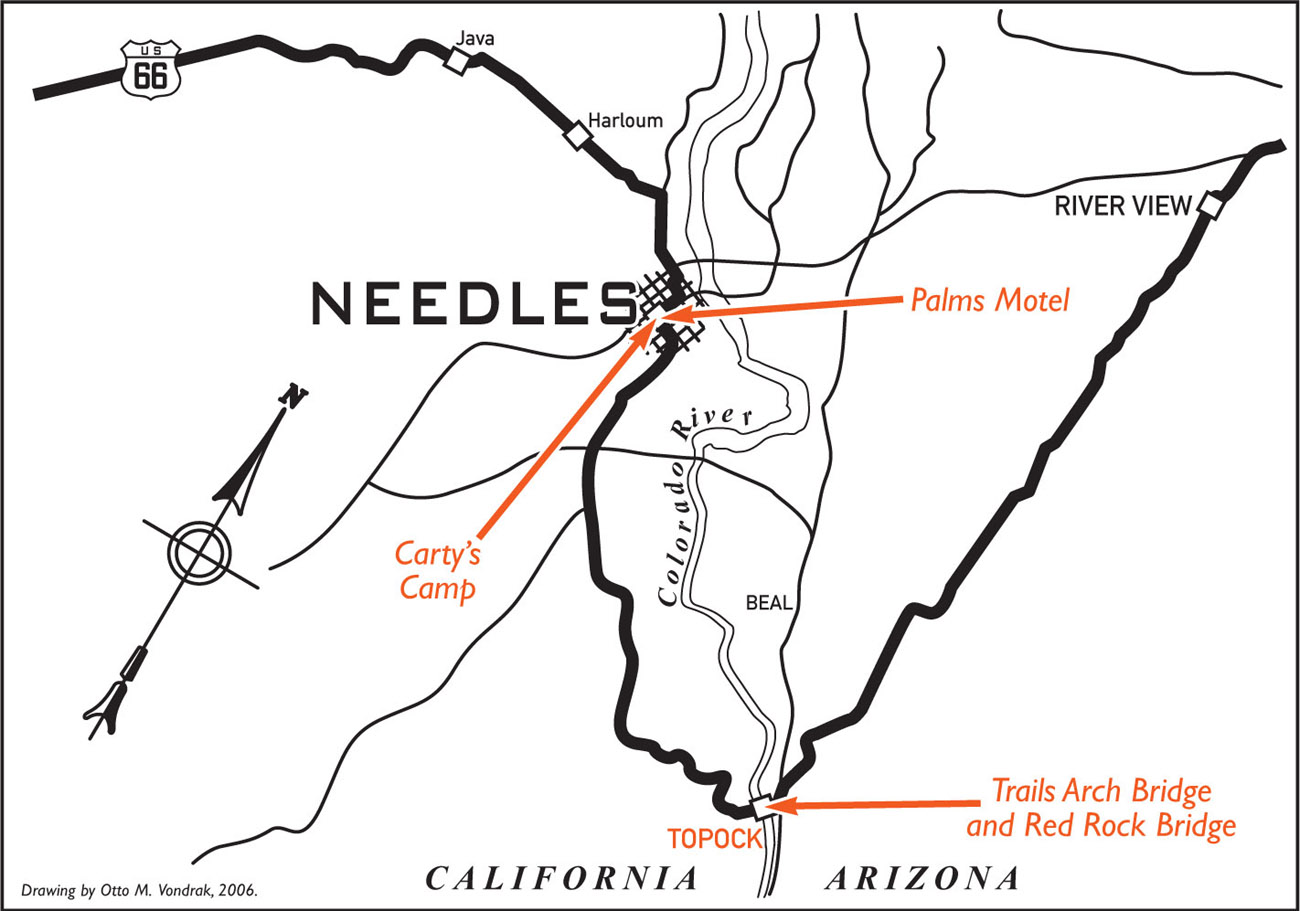

The first bridge to cross the Colorado River at Topock was a wooden structure built by the railroad in 1883. In 1890 the Phoenix Bridge Company built one of the first steel bridges in the country, the Red Rock Bridge, to replace the outdated wooden bridge for the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad. With a construction cost of almost a half million dollars, the Red Rock Bridge was thought to be excessive and very expensive at the time. Trains quickly became heavier and stressed the limits of the new steel bridge. Modifications were needed to strengthen the structure, first in 1901, then again in 1911.

If you were not traveling by train, crossing the Colorado was a different story. Prior to the automobile, the Needles Ferry carried horse and foot traffic across the Colorado beginning in 1890. When the automobile appeared on the scene, this ferry served motor traffic traveling the Old National Trails Highway. In 1914 a massive flood took out the ferry service, leaving travelers stranded on both sides of the river. Wooden planks were laid over the railroad ties of the bridge. Motorists were allowed to cross between trains, as railroad employees with train schedules in hand coordinated the crossings.

The Red Rock Bridge continued to carry automobile traffic until the Old Trails Arch Bridge was completed on February 20, 1916. The first alignment of Route 66 crossed the Colorado River from Topock, Arizona, to Needles, California (14 miles to the west) via this bridge, seen in the background of the postcard and photograph. The Old Trails Arch Bridge carried the dirt path of the National Old Trails Highway for more than 10 years prior to the designation of U.S. Highway 66 in 1926. Located about 800 feet downstream of the Red Rock Bridge, the Old Trails Arch Bridge was a marvel in its own right. For 12 years it stood as the longest three-hinged arch bridge in the country.

Although it was quite the engineering accomplishment at the time, the bridge had its limitations. The load limit was only 11 tons, and the roadbed was so narrow that bus and truck traffic were able to cross only one way at a time. A warning sign was posted at both ends of the bridge to help avoid head-on collisions: “One Way for Trucks and Buses.” This restriction proved quite annoying to motorists from time to time, but for the most part traffic was light enough and did not pose serious problems until later years.

With the coming of World War II, truck traffic on all of America’s highways increased dramatically. This increase, along with the growing size of vehicles, spelled the beginning of the end for the Old Trails Arch Bridge. Automobile travel and truck traffic continued to grow by leaps and bounds, especially in the years immediately following World War II. The graceful old bridge was no longer able to handle the heavy traffic load that Highway 66 now supported. A new automobile crossing over the Colorado was desperately needed.

In 1945 the Santa Fe Railway established a new river crossing, opening the possibility for auto traffic to once again flow over the Red Rock Bridge. It was determined that an adequate crossing was already in place and a new bridge did not need to be built. The rails and ties were removed from the Red Rock Bridge and concrete was poured for the roadbed. On May 21, 1947, the Red Rock Railroad Bridge conversion was complete, and automobile traffic once again flowed over the venerable bridge. When the new four-lane steel bridge carrying Interstate 40 was completed in 1966, the Red Rock Bridge was unceremoniously closed and remained abandoned until it was completely dismantled in 1976. Only the concrete pilings remain.

The Old Trails Arch Bridge, once in danger of the same fate, was again put to use and today carries a natural gas pipeline from Texas for the Pacific Gas and Electric Company. For a nice look at the Old Trails Arch Bridge in its heyday, watch the Joads cross it in the movie version of John Steinbeck’s novel The Grapes of Wrath.

c. 1931

While visiting the Grand Canyon, Santa Fe Railway employee Bill Carty stayed in a cabin that was something of a tent/cabin hybrid. Upon his return to Needles, he enthusiastically brought up the idea of starting a tourist camp and auto court to a friend and coworker, one Mr. Manskar. Manskar thought it was a great idea to open an auto camp in Needles, and in 1925 Carty’s Camp became a reality. Both the Carty and Manskar families were involved in operating the facility, and both lived on the premises for a time. Manskar grew weary of the business, though, and Carty eventually bought out his interest. Carty quit his position at the railroad to manage the business full time.

The facility eventually expanded to include a gas station, garage, cottages, campground, and a motel, which Carty dubbed Havasu Court. Havasu Court consisted of 12 cabins, each with an attached garage, in two back-to-back rows. Shade in Needles is gold, especially in the summer months when temperatures can climb into the high 120s, and a small, shaded picnic area located directly across from the camp was a favorite among customers. Carty’s Camp flourished and became the place to stay in Needles.

Carty retired from the business in 1948 and sold the camp to Charles Canterbury and Loren Armes. Both the Canterbury and Armes families shared the day-to-day operations, and, like their predecessors, both families lived on-site. Mildred Armes remembers Route 66 as a gold mine that provided customers from 6 a.m. to 10 p.m. every day. “We worked our tails off,” she was quoted as saying. The two families also built and operated a gas station in Needles called the C&A Chevron Gas Station, which included a lunchroom and store. Eventually the families retired from the business, and the camp closed shortly thereafter. Not much is left of the remaining structures, on which the desert climate has taken its toll. Today a few of the cabins are used for storage.

Carty’s Camp was a true reflection of what auto travel on early Highway 66 was all about. The Joad family passed in front of Carty’s in the screen version of The Grapes of Wrath. That appearance in itself makes the site of Carty’s Camp hallowed grounds. Just standing on the property, one hearkens back to the days of early auto travel when excitement, adventure, and even danger were part of an automobile trip. That real sense of adventure is captured on a note written on the back of a postcard dated June 24, 1931: “Dear Daddie, It is now 11:55 p.m. We are going on across the desert tonight. It is very hot and dry. We will write when we get on the other side. Love Florence.”

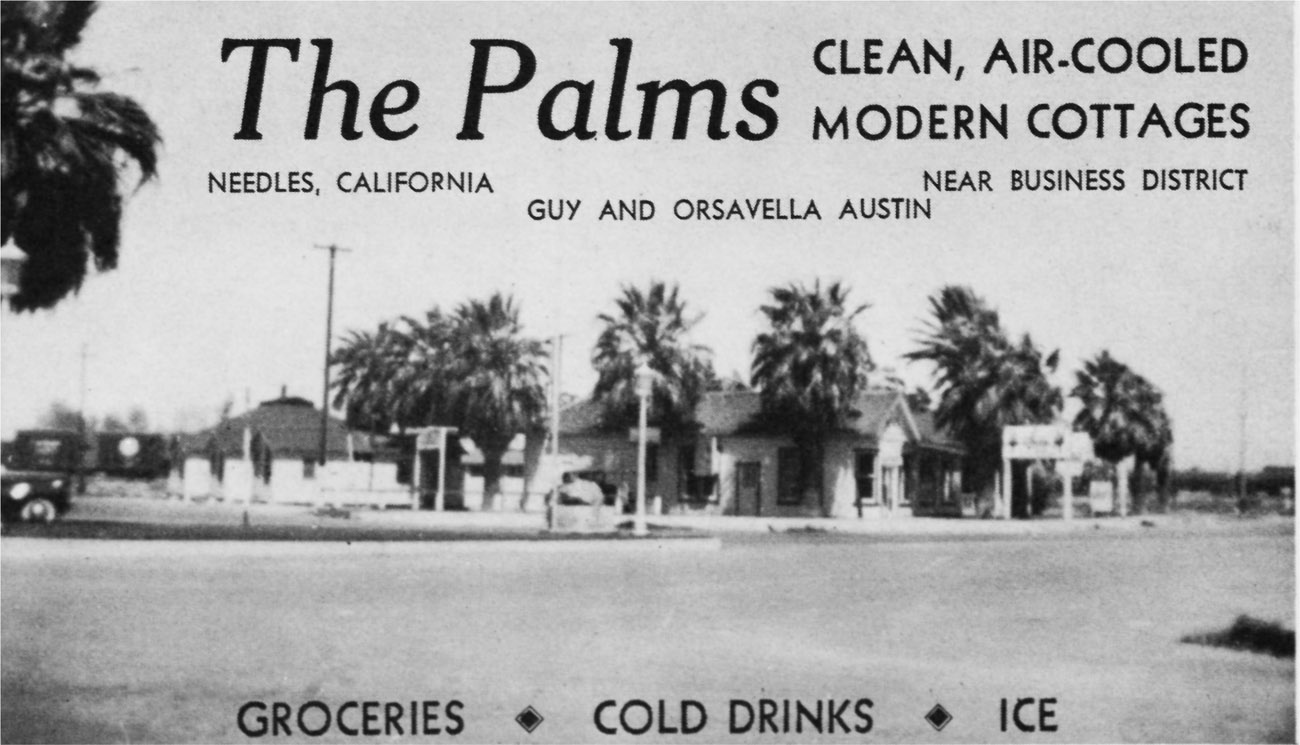

c. 1946

Needles was always an important stop along Highway 66. For westbound travelers, it was the jumping-off point for crossing the treacherous Mojave. Those headed east and emerging from the Mojave took a deep breath, gave a sigh of relief, and thanked their lucky stars to have made it without incident.

The Palms Motel is located on the eastern edge of town where Broadway and Front Street split. The motel’s origins date to the 1920s, when it was located on the west edge of town. In the motel business they say location is everything, and the cabins were eventually moved to their current location in the late 1930s. Prior to the move, the eastern location was the site of a tent camp for the railroad, and the Palms soon became a favorite sleepover for railroad employees.

Along with Carty’s Camp, the Palms Motel was one of the first tourist facilities that weary westbound travelers saw when approaching Needles. Operated by Guy and Orsavella Austin in its early days, it consisted of 14 units, 8 of which had kitchen facilities.

The Palms has gone through a succession of owners. In 1991 Hank and Edna Wilde purchased the property from Luis Bravo and transformed the motel into a bed and breakfast renamed the Old Trails Inn. The B&B never really took off, and it closed in 1997. Bravo reacquired the property and proceeded to fully renovate each unit. The walls were stripped bare, and new plumbing and wiring were installed throughout the property. The Palms currently has 16 units, all of which are rented monthly.

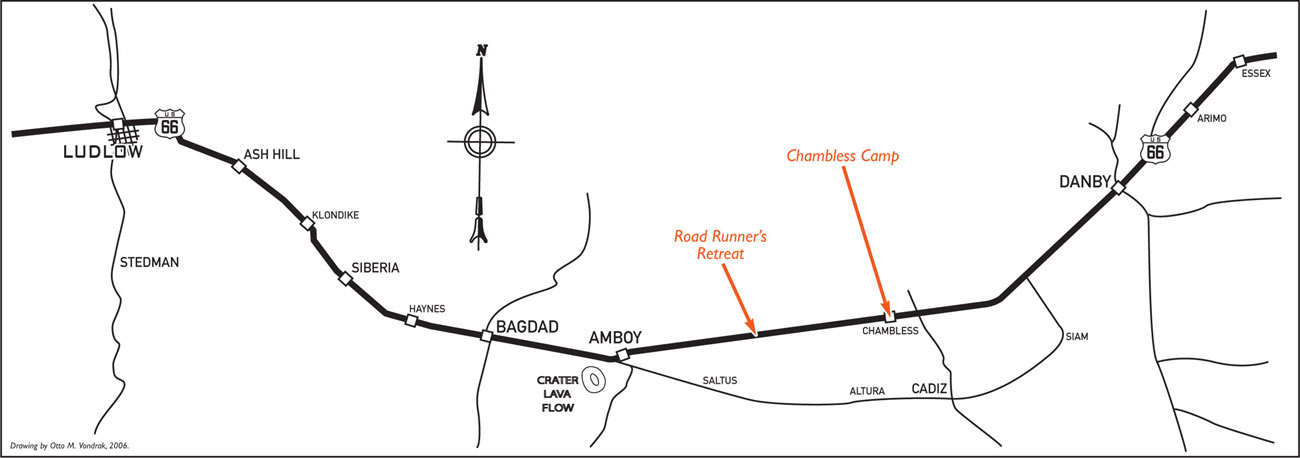

c. 1932

In the 1920s a widower named James A. Chambless, along with his two children, relocated from Arkansas to the Amboy, California, area. In 1932 he built the small Chambless Camp out of handmade blocks, hoping to cash in on the burgeoning auto-tourist trade. He quickly expanded the business into a full-service stop that included a service station, café, grocery, and cabins. The main building, housing the grocery and service station, featured a large canopy over the pumps to provide shade to customers while they were filling up. Jack D. Rittenhouse, in his 1946 book, A Guidebook to Highway 66, describes the Chambless Camp as “one of the few shady spots in the entire desert route.”

Much of the business relied on first-time desert travelers who unknowingly attempted to cross the desert during the heat of the day. Wreckers were at the ready, mechanics were on duty, the café was open to feed stranded travelers, and cabins were available for overnight stays if repairs were extensive. Sometime in the late 1930s, Chambless was remarried to a woman named Fannie Gould. She took over the reins of the business and turned the Chambless Camp into a virtual desert oasis, adding, among other things, a fishpond and a sprawling rose garden, both very unusual sights in this region of the Mojave Desert. In addition, a picnic area lined with acacia trees provided shade and added the oasis-like feel of the grounds.

The early 1970s saw the opening of Interstate 40, and most businesses along this stretch of Highway 66 soon closed. Sometime in the early 1990s, the canopy over the gasoline pumps at the Chambless Camp was destroyed in a violent windstorm, and more recently the pumps were removed. Gus Lizalde bought the property in the early 1990s and planned to renovate the camp to include a Mexican restaurant, a remodeled service station, and RV hookups. The restaurant was open for a time, but the rest of the renovations never really got off the ground. The old cabins still stand and are rented to workers who farm the vineyards in nearby Cadiz. The majority of the property remains abandoned and is, inch by inch, being slowly reclaimed by the harsh desert elements.

ROAD RUNNER’S RETREAT, EAST AMBOY

c. 1960

Located 9 miles east of Amboy and a short half mile west of the Chambless Camp, the Road Runner’s Retreat was a relative latecomer along Route 66 in this part of the Mojave, opening sometime in the mid- to late 1950s. The restaurant served classic road food and was an extremely popular stop for truckers. The interstate bypassed this section of Highway 66 in the early 1970s, leaving most of the businesses from Essex to Ludlow, including the Road Runner’s Retreat, high and dry.

In 1988 the Road Runner’s Retreat received a face-lift when Dodge decided to film a television commercial on the site. For a couple of days the gas station and restaurant once again jumped with the hustle and bustle of people coming and going. The clamor of cars pulling in and out of the gas station and restaurant must have truly been a strange sight for the local wildlife. Then, just as suddenly as the silence was broken, order was restored, and the wild creatures and birds reinhabited the empty structures. It is stunning how loud the quiet is here and how much of an outsider humans truly are. As a light breeze breaks the silence and makes its way through the hollow buildings, perhaps a faint sound, barely audible, can be heard—maybe it’s a friendly “Beep beep.”

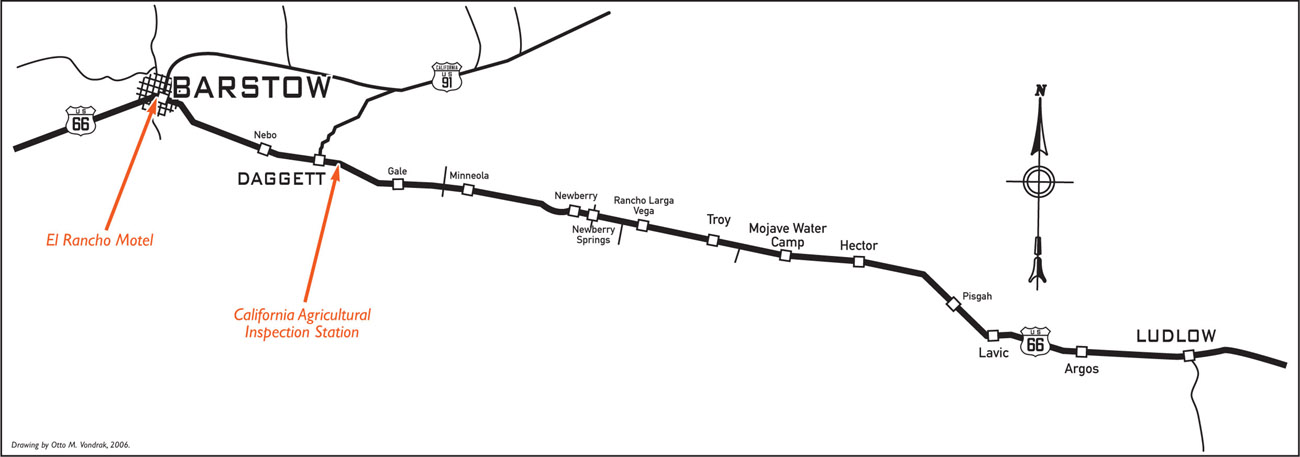

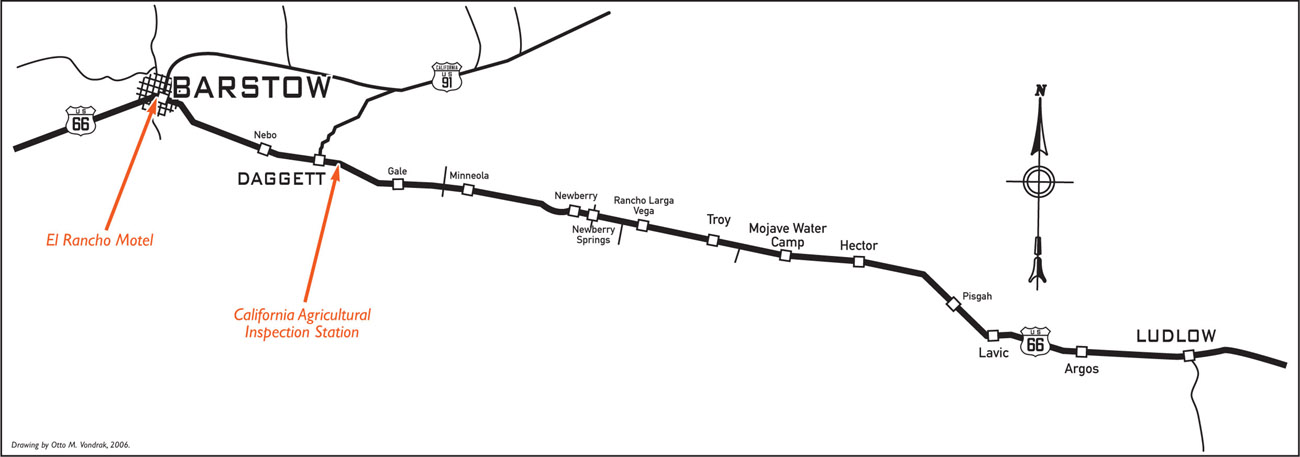

CALIFORNIA AGRICULTURAL INSPECTION STATION, DAGGETT

c. 1953

This California Agricultural Inspection Station was built in 1953 and was the third of three such stations built in Daggett. Agricultural inspection stations were set up all around California in an effort to prevent the import and transport of diseased fruits and plants and harmful parasites. These searches prevented fast-moving diseases and parasites from devastating entire crops and so protected the state’s large, important citrus and vegetable industries. All westbound traffic was stopped, and each car was given a complete and thorough search. Plants, fruits, and vegetables were quickly confiscated, and incoming motorists were then given an inspection and admission certificate allowing them to pass.

Interstate 40 eventually replaced Route 66 in the area, and the Daggett station was permanently shut down in 1967. (The current inspection station sits on the super slab just outside of Needles.) The second of the three inspection stations was built in 1930 and is the one seen in the 1940 movie version of The Grapes of Wrath. Sadly, during the 1930s, these inspection stations and dozens of makeshift stations around the state were often used to weed out “undesirables” as thousands fled the choking, dust-ridden plains of the Midwest. Thousands of people were turned away when inspectors deemed them unfit to pass. It is said that many of these displaced Okies and Arkies, without the means to satisfy inspectors—and virtually stripped of all hope for a future—walked despondently into the desert, never to be seen again.

c. 1947

A man named Cliff Chase built the El Rancho Motel in 1947 entirely from old railroad ties salvaged from the Tonopah & Tidewater Railroad. During the heyday of Route 66, Barstow became an essential stop for travelers arriving from the tough Mojave portion of the road or preparing themselves for the dreaded desert journey. The El Rancho provided excellent facilities, and the motel was regularly filled to capacity. Originally the El Rancho contained 50 rooms, but at its peak it featured 101 rooms, 26 of them with kitchenettes. In 1947 room rates started at $4.50 a night for a single bed and went up from there. A 100-foot-tall neon sign later erected on the property became a beacon that could be seen for miles.

In 1979 the motel was closed to the public and rented exclusively by the Santa Fe Railway and its employees. When Interstates 15 and 40 were completed, newer and more convenient motels were built alongside the new highways, and the El Rancho slowly fell into disrepair. In 1987 Rick Byers bought the property and began the process of restoration. It was reopened only to close five years later, again deteriorating due to hard times and poor management. In 1994 Byers sank another $300,000 into a second restoration, which included a Route 66 Visitor’s Center adjacent to the motel office. Unfortunately, current traffic on Historic Route 66 did not generate sufficient business to justify keeping the motel well maintained, and once again the motel is headed on a downward slide. Surviving several subsequent ownership changes, the El Rancho continues to operate as a senior housing facility. Willing motorists can still spend the night at the vintage motel, as several rooms have been set aside to accommodate the courageous and weary tourist.

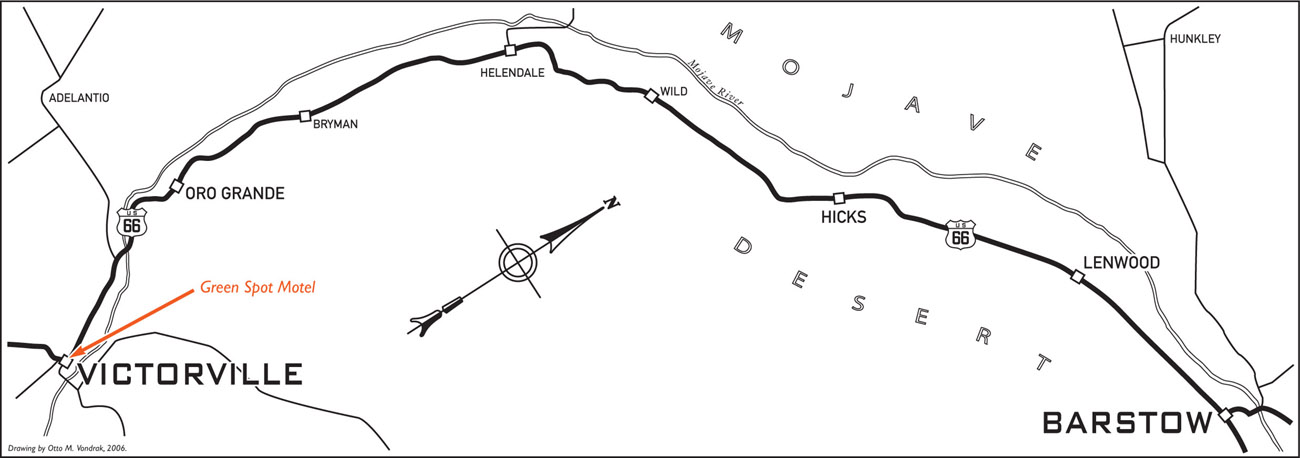

c. 1947

Heading west through Victorville, the path of Highway 66 ran down D Street until reaching Seventh Street, where the Mother Road took a rare 90-degree turn and continued on through town. One block after the turn, near the corner of Seventh and C Streets, sits the landmark Green Spot Motel. In its heyday Victorville served as backdrop for hundreds of Hollywood Westerns and as a getaway for the stars. The Green Spot Motel was the crème de la crème. The motel consisted of 20 gable-roofed buildings, each containing two guest units with flat-roofed carports connecting them. The buildings were arranged in a U shape with 10 across the rear and 5 along each side. In the center was a magnificently landscaped courtyard that later contained a swimming pool.

The Green Spot was at one time part of the United Auto Courts system and billed as “Truly De Luxe.” A café, also called the Green Spot, was located on the corner of C Street and Seventh. Very popular in its day, the café was frequented by many a celebrity. Orson Wells was rumored to have written much of his material in one of the booths. In 1953 the Green Spot Café burned to the ground.

After the interstate bypass was built in 1972, the motel began the typical decline and soon became home to drug dealing and prostitution. In 1982, the 1940s star Kay Aldridge, best known for her portrayal of Nyoka in the serial Perils of Nyoka, married Harry Nasland, who was then part owner of the Green Spot Motel. He died after a few months of marriage, and Aldridge inherited his interest in the motel. She vowed to clean up the place and restore it to its original splendor as a premier getaway and rest stop. It was more than she could handle. She eventually became disillusioned and moved to Maine. A plaque located on the front wall next to the entrance arch reads “Nyoka’s Hideaway,” bearing witness to her fondness for the Green Spot.

Aldridge sold the motel to Benjamin Wu and Nancy Wei, who operated it until 1995. Aldridge died of a heart attack on January 12, 1995, and two months later Wei was sentenced to 13 years in prison for shooting and killing her husband. Aldridge’s estate foreclosed on the property, and the Green Spot sat dormant. It was eventually sold to Hemant Patel in 2001. The Green Spot Motel currently rents to weekly and monthly tenants and is showing signs of a slight recovery.

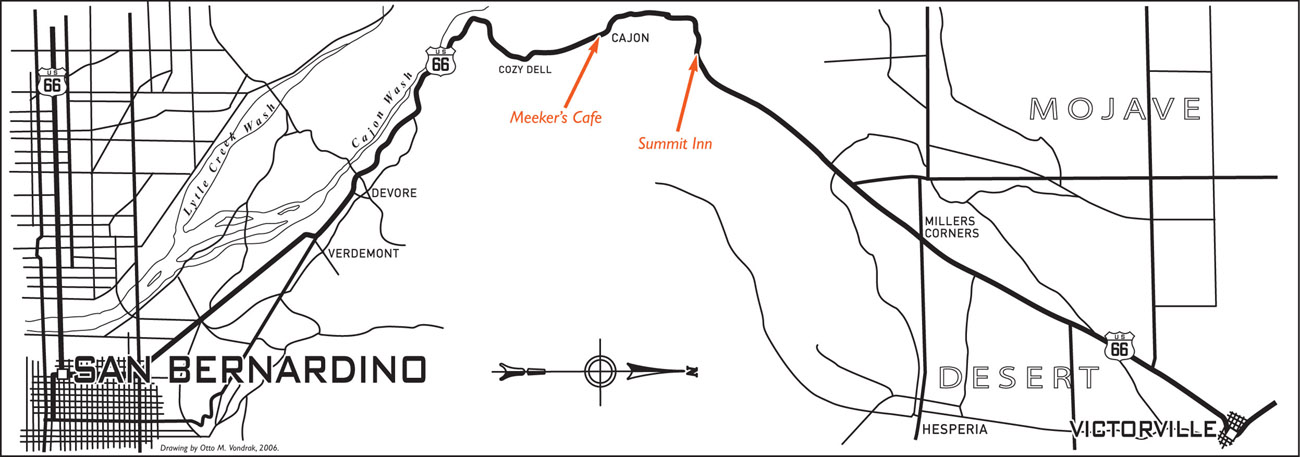

c. 1957

The Summit Inn was built in 1952 by Burton and Dorothy Riley on what was then two-lane Route 66. The roadbed sat on the east side of the restaurant at the time of the hotel’s construction, but was moved in 1955 to its current location on the west side when it was upgraded to four-lane status. The restaurant sat on the west side of the road when C. A. Stevens purchased the business from the Rileys on October 13, 1966. Stevens has owned and operated it ever since.

In 1969 and 1970, Interstate 15 obliterated the Mother Road in this area, but the Summit Inn survived the changes and continues to serve good road fare. In 1969 Stevens moved the service station end of the business closer to the off-ramp that was being built as part of the new interstate upgrade. As late as 1972, water had to be hauled to the Summit Inn by truck and was pumped into the restaurant from a storage tank located alongside the restaurant.

When Stevens bought the business, he also acquired a waitress by the name of Hilda Fish, who continued working at the Summit Inn until retirement in 2002. During the late 1980s, representatives of the Denny’s Corporation approached Stevens with an offer to convert the restaurant. When Stevens asked Fish what she thought of the idea, she responded, “You put a Denny’s here and I quit.” The Denny’s was never built, and Fish stayed.

The Summit Inn continues to be a popular stop on the Cajon Pass—so popular that even the King himself, Elvis Presley, was reported to have paid a visit. According to Fish, Elvis stopped at the Summit Inn one night, but left hurriedly when he saw that none of his records were in the jukebox. It’s true—Elvis has left the building.

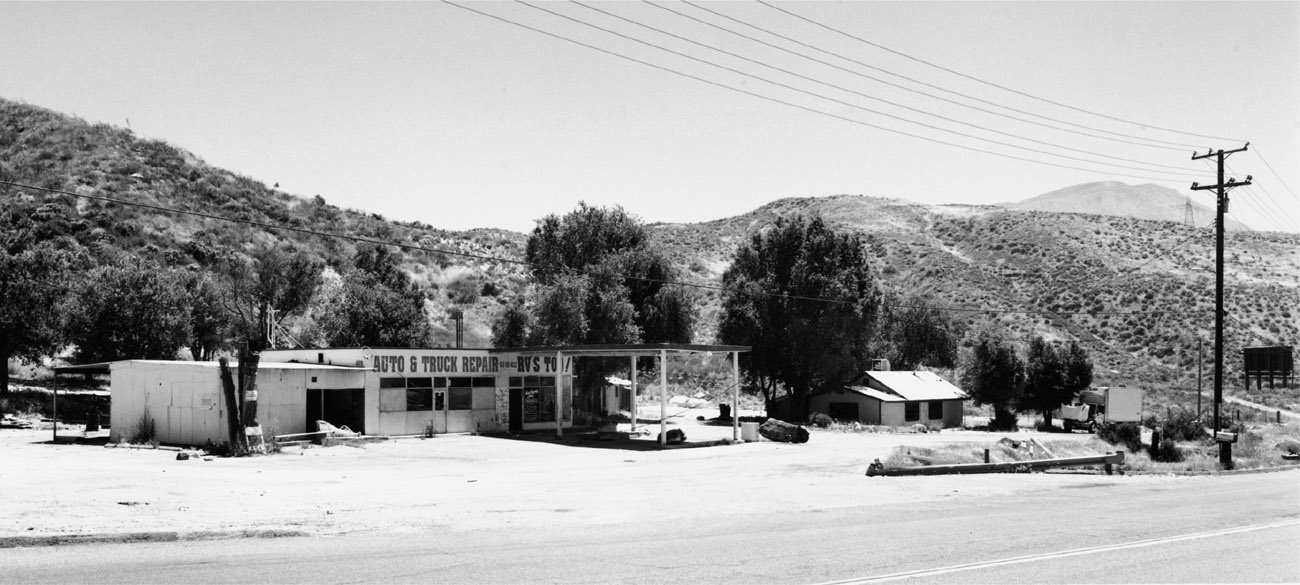

c. 1932

The path over and through the Cajon Pass has gone through several forms and variations. Early on it was a narrow, difficult-to-navigate pack trail known as the Spanish Trail. By 1855 the trail was moved farther east, and although improved, it added several miles to the trip. In 1861, with financial backing from Henry M. Willis and George L. Tucker, John Brown built a new road for which he would charge a toll of 25 cents for a man and his horse and $1 for a horse-driven wagon. As time went on, the path through the pass evolved and has been known as Old Trails Highway, Highway 66, and, currently, Interstate 15.

In 1919 Marion Meeker built a small gas station and café on leased land next to Camp Cajon on what was then Old Trails Highway. Built by William Marion Bristol, Camp Cajon was a rest stop and picnic area that acted as a welcome station at the “Gateway to Southern California.” Meeker’s brother, Ezra, soon arrived to lend a hand. By 1929 the brothers had saved enough money to buy their own land, and they built a new place just down the road. They soon had their gas station, café, and store up and running, along with an auto court called Meeker’s Sunrise Cabins.

The year 1946 saw the complete destruction of the café and garage by a runaway truck that luckily missed the gasoline pumps. In the mid-1950s the whole complex was torn down to make room for the new four-lane Route 66. Only two cabins survived, and they were relocated, combined, and converted into a small house. A new garage, café, and gas station were built on the remaining property. Ezra ran the place until his death in 1966. His second wife, Mabel, who was also known as the “Angel of Cajon Pass,” lived in the converted house until 2002, when she moved to a senior-care facility.

The Cajon Pass has a wonderfully rich history that can be traced back well over 150 years. Although little remains of Camp Cajon and Meeker’s Café, the pathway through the pass continues to be a vital transportation corridor to this day.

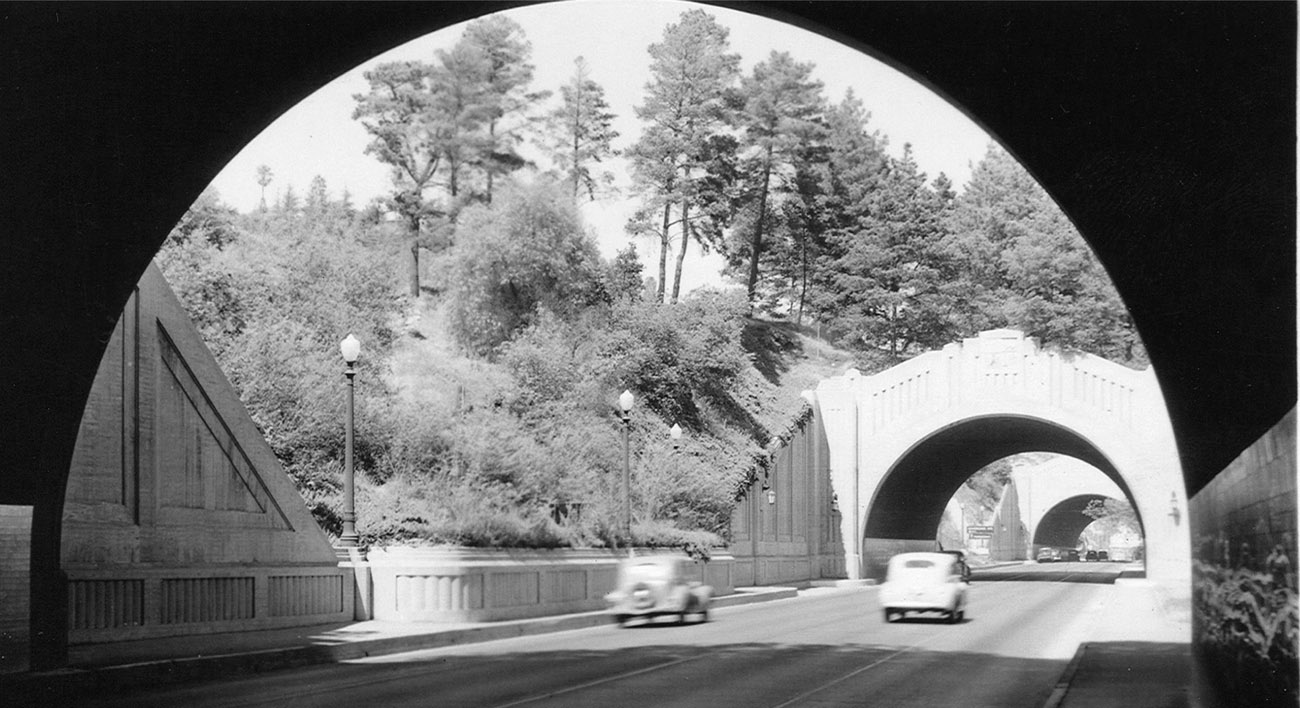

FIGUEROA STREET TUNNELS/ARROYO SECO PARKWAY, LOS ANGELES

c. 1943

Construction of three of the four Figueroa Street Tunnels was completed in 1931, and the fourth and final tunnel was completed in 1936. That same year saw Route 66 rerouted through the tunnels. The downtown Los Angeles terminus at Broadway and Seventh changed to Olympic and Lincoln Boulevard in Santa Monica and was reached via Sunset Boulevard and Santa Monica Boulevard.

Construction of the Arroyo Seco Parkway, extending from Pasadena en route to Los Angeles, began in 1938. December 30, 1940, saw the completion and opening of the beautiful, groundbreaking parkway. This Highway 66 bypass alignment was considered to be the first freeway west of the Mississippi. In 1942 two-way traffic through the Figueroa Tunnels was altered to handle one-way, northbound traffic, and the Arroyo Seco Parkway/Route 66 was extended toward downtown Los Angeles to include the Figueroa Street Tunnels.

Today, although Arroyo Seco Parkway is a beautiful drive, safety is a big concern. When dedicated, parkway speeds were set at a maximum of 45 miles per hour. With tight curves, narrow lanes, lack of shoulder space, and very little room for entering and exiting, traveling at today’s speeds makes navigating the parkway somewhat challenging. It is now listed as a National Scenic Byway and is well worth the effort to explore its historic path.