intrusive, intransigent, invisible

A round 845 CE, a chronicler named Ignatios confessed how he felt when viewing pictures of human pain: “Who seeing a man tortured to death . . . depicted in material colours . . . would not leave the scene beating his breast in the affliction of his heart? . . . Who would not be filled with apprehension and subdued by fear?”

1 The emotionalism spurred by such visions of distress (Ignatios was describing a mural in Constantinople) arose not from detached contemplation of a text, but from an artist’s conjuring of a parallel, immediate experience. The world of the flayed prophet or the disemboweled saint was impossibly distant from the Byzantine viewer’s here-and-now. And yet the breast-beating “afflicted heart” of the beholder was inflamed precisely because “material colors” individualized her experience from a faraway place and time. With gleaming tesserae Byzantine artists made pain—the most personal of phenomena—public. Illuminating Christian dogma, such art trafficked in glaring contradictions-martyr in agony yet blissful, Christ as all human yet divine, saint as living yet dead. Orthodoxy subsisted in paradox and held that truth dwelt only in the otherworldly. In a very different way, so did Soviet poster art. While retaining church art’s high-pitched didacticism, an art such as Viktor Koretsky’s exploded the Byzantine icon’s mystical impulses, its magic. For Russian posters, as one scholar has put it, “had to communicate under pressure”;

2 they were forced, in the Soviet Union, to assert themselves in urban realms that were unfocused, noisy, and in bewildering flux. Mystical and paradoxical elements risked an obfuscation of message. The Red Army soldier points at the viewer; tractors crawl in phalanxes past tanned, squinting peasants. These are easy and predictable images to map onto a narrative of the Russian icon “disenchanted” (Kazimir Malevich did as much).

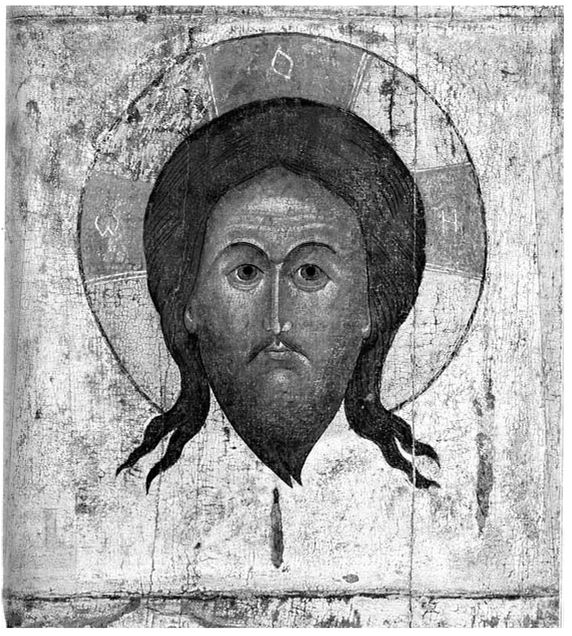

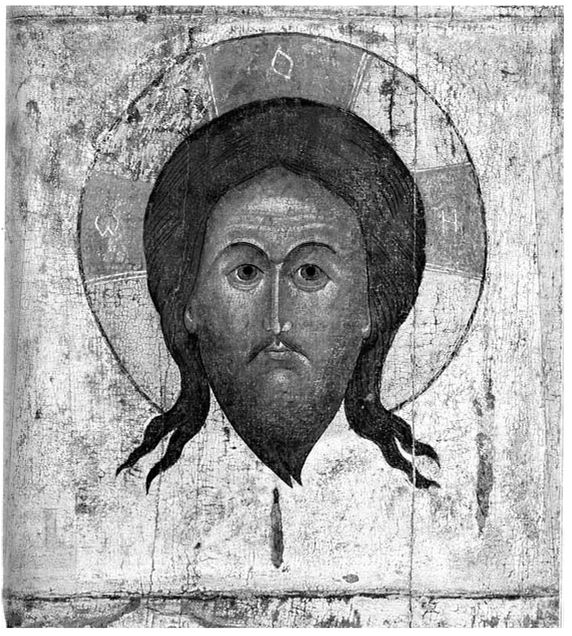

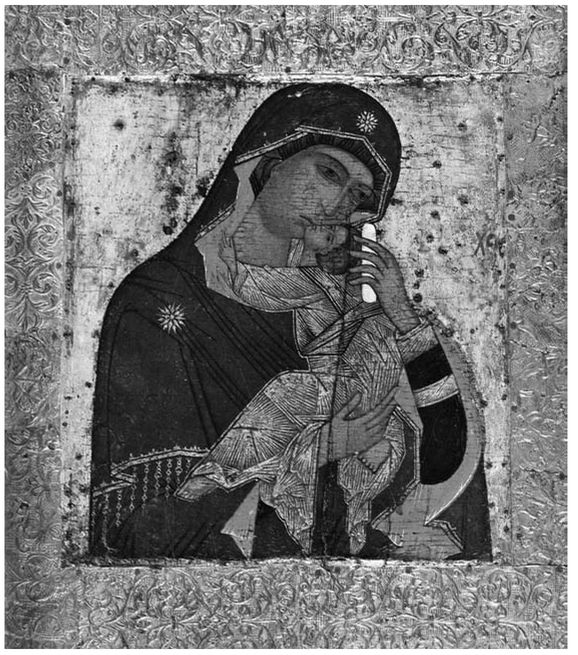

Figure 1. Moscow, Mandylion, late fifteenth century, egg tempera on panel. [Wijenburgh Foundation, Netherlands]

Figure 2. Viktor Koretsky, Capitalism Is War, the People’s Suffering, and Tears (Kapitalizm—Eto voina, narodnoe gore, i slezy), 1960s, original maquette. [Ne boltai! Collection]

And yet the “suffering” image of the late Soviet posters is a different chapter of this story. Like the icon, it asked the viewer to look beyond logic. And like the icon, it asked the viewer to incessantly place her immediate needs in the context of a philosophical totality. The Byzantine viewer would presumably never know what it was like to be burned alive, to be beaten or lynched. Yet the massive and opulent images of martyrdom overwhelmed the senses, seeking to evoke a sensation that suggested these feelings. Similarly, these posters wielded the vividness of the large-scale picture to educe an approximation of conditions that could not in essence be logically explained or even really seen—agony, fear, conviction, loss. Like a Byzantine painting, the effective Soviet poster was meant to instruct. Yet it was also meant to agitate, to spur an empathetic pang. And it was meant, as this essay will examine, to do so again, and again, and again.

i.

The earliest wall posters were produced in Rome; in Pompeii paintings survive from the first century BCE, advertising festivals, election candidates, circuses, or entertainment. Some of the earliest Russian broadsheets, printed in woodcut, deal with the same subjects. Scrawled advertisements for wares or professions were hung outside tavern doors or public houses throughout the Middle Ages in Muscovy. When print technology belatedly arrived in tsarist Russia in the 1590s, sheets were often used as coverings for walls and interior rooms. The woodcuts, aside from brandishing information, rendered momentarily new the surface of any siding, railcar, or hut.

In fact the Russian word for poster,

Π a

a a

a

derives from the German

Plakat, literally meaning to post up, which itself comes from the old Dutch verb

aanplakken (to stick or place over). And it was from German and Dutch middle-class broadsheet culture of earlier centuries that Russian notions of mass-produced postings seem to have arisen.

Figure 3. Germany, Spiritual Brawling (Geistlicher Rauffhandel), ca. 1590, woodcut. [Sammlung der Staatlichen Galerie Moritzburg, Halle]

In Reformation Germany, satirical Flugblätter—broadsheets, or handbills—proved speedy forums for publicizing news, edicts, or theological debates. More commonly, however, they emerged as a means of public announcement (and, for the first time, visual illustration) of the extraordinary or exotic. Monstrous births, heraldic comets, meteorological oddities, new-world discoveries—all could be seen, posted in print at inns or town halls, in a manner that was easy to suture into larger campaigns of confessional parody or caricature. Some of the earliest prints were those showing martyr-doms—gruesome, bloody, and hallucinatory episodes from Christian history. Prints became staples of life, not just in their ability to disseminate information, but as a new means of artist employment: in South Germany painters who had been left jobless by Protestant bans on images turned to broadsheets as a means of making a living. Posters emerged as places for artists to essay the propagandistic, the miraculous, the disorienting. The idea of the poster that was carried over to Russia in the late eighteenth century was, on the one hand, as a devotional vehicle, and on the other as a site of the spectacular, the painful, and the monstrous.

Figure 4. Advertisement for an Olympic Circus, St. Petersburg, 1825, woodcut. [Location unknown]

The Russian lubok (on which more shortly), like the broadsheets of Reformation Germany, became a frame for unfamiliar sights, astronomical oddities—quite literally, visions. These were markedly different from the seductive, empty spectacles offered by an inchoate advertising culture at the same time. What the lubok publicized to its public in Russia was not a product or experience to consume but a marvel, a situation.

ii.

Lithography was invented in France in 1796, and chromolithography in 1837; “offset” color posters became the dominant kind of public printed image, first in Europe and later in Russia. Large-scale paper production and faster drying inks (with xylene and benzene) appeared in the 1870s. In tandem with innovations in photographic technology, these allowed unprecedented print runs, at the same time that railroads permitted posters to girdle entire continents. Bolshevism, drenched in metaphors of technology, speed, and transformation, embraced the poster’s power and mercantilist means. It wielded the poster both as a vehicle for and as a symbol of proletarian dynamism. As Lissitzky put it: “the poster is the traditional book ... flung in all directions.”

3

Figure 5. Manifestation Above the City of Cartagena, 28 December 1743, 1744, colored engraving. [Pushkin Museum, Moscow]

And it was the “flinging”—as much as what those dismembered books showed—that mattered for Bolshevism’s spread. During the Russian Civil War some posters were issued in runs of up to five thousand. By the time of the Second Five-Year Plan (the economic program of the Soviet Union), placards were printed in editions of two hundred thousand and distributed by railway from Baku to Vilnius to Tashkent. The “agit-trains” of the Civil War actually housed, along with radio stations and bookshops, printing presses that issued posters that could be (quite literally) flung into villages. Implicit in these operations was, as Lenin himself noted, a nod to industrialization’s might.

4 And nestled within the poster’s medium, too, was a critique of the “fine” art object. Russian posters were fashioned of cheap and low-durability materials.

5 Aimed at a largely illiterate population, the posters trafficked in the crudest of stereotypes, cartoon-like caricature, simple jumpings of cause to effect.

Figure 6. El Lissitzky, Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge, 1919, poster. [Eindhoven, Van Abbe Museum]

A 1931 Central Committee resolution called for specific study of how the posters were received, hypothesizing that city dwellers could be effectively addressed only with arresting, immediate poster imagery. Peasants, paradoxically, necessitated more complex designs because they could be expected to stop and devotionally contemplate images in slow detail.

Figure 7. Vladimir Mayakovsky, ROSTA Window No. 858, 1921, onepage offprint. [Location unknown]

They had time. Across both country and city, the poster was a cipher for completely modern scales of mass politics; a staging of visual confrontation targeting the individual within the indistinct mass, whether it was the peasant or the urbanite. Russian posters provided information about politics, economics, culture, hygiene, and morality. They harangued and declared—they were never an invitation to engage in dialogue.

iii.

Posters work specifically through the negotiation of self and other. In the case of late Soviet posters, they dealt with crude types that could not—and likely would not—be viewed in one’s lifetime. Like icons—the hypercharged antecedents for some of Viktor Koretsky’s specific designs—posters might be said to operate through a visual rhetoric of intrusion. Icons did not seek to pictorially extend the viewer’s space, to create the illusion of a stage, as did Western perspective, which sought to evoke an everyday experience simulated through a window.

Figure 8. Moscow, Mother of God, sixteenth century, tempera on panel. [Tretiakov Gallery, Moscow]

Figure 9. Viktor Koretsky, Save Us! (Spasi!), 1942, original maquette. [Ne boltai! Collection]

Figure 10. Viktor Koretsky, Freedom for All African Nations! (Svobodu vsem narodam Afriki!), ca. 1970s, black-and-white photograph. [Ne boltai! Collection]

Rather, icons—like the early posters and, differently, Koretsky’s maquettes—sought to block off the expected worldview and instead to project the unfamiliar into it, to impinge upon the quotidian by representing an arena of dazzling otherness. In the 1920s a Russian theologian asserted that a pictorial structure’s task was not duplication of the world, but rather “a certain spiritual arousal (

npo y

y ∂e

∂e ue

ue), a jolt that rouses one’s attention to reality itself.”

6 Soviet images rendered this arousal revolutionary. One need only think of how the earliest posters mounted in Moscow by the Bolsheviks during the Civil War were themselves “windows” (

okna ROSTA [Russian Telegraph Agency]), large stenciled posters illustrating party policy or economic news placed over abandoned shop fronts beginning in 1919. Intended to supplant the barren, tawdry (and, at the time, empty) “spaces” of consumption with flat, brilliant, unrelenting walls of pedagogy, the ROSTA windows instructed readers, with rhyming couplets and schematic illustrations, how to sort potatoes, where to pay their taxes, why they should obtain a smallpox inoculation. The messages changed from day to day. In Moscow lithography was used, but in Odessa paper was so scarce that the designs were transferred to plywood, displayed for a day, and then painted over with the most current news. Compositionally these images aimed to turn the “lie of bourgeois perspectivism”—the “sated gaze”—in on itself. The

okna were the silent, Orthodox iconostasis transformed into a working rostrum—a fitting metaphor for the Revolution itself.

And likewise, these illustrations depicted the unexpected intrusion of unseeable, even dangerous, worlds into the realm of the viewer. As threat, utopia, or dream, it was the Unseen—as explored elsewhere in this book—that held the most power in late Soviet modernity. The laughable generality of later Socialist Realist communist images—their deliberate obviousness—was, in fact, a revolutionary move: it refused the rhetoric of savvy consumption that saturated the ocularcentrism of Western advertising culture. Nothing was laid out for the eye. It had to be grasped by association. By the very end of the USSR, the Soviet poster, like its Reformation forebears, had gone full circle, retooling the sexy and idolatrous with the utterly banal.

iv.

Russian posters were bluntly instrumental in use, non-site specific, ephemeral. Artist Vladimir Mayakovsky spoke of them as “telegraphic bulletins.” Even the more avant-gardist posters were nominally proletarian in theme and were intended to take any number of forms and sizes, to be rescaled, repurposed, and printed in dif ferent formats; in the 1930s journals appeared dedicated solely to reviews, reproduction, and analysis of posters:

Produktsiia izobrazitel’nykh iskusstv [Art Production] (begun in 1932) and

Plakat i khudozhestvennaia re-

produktsiia [Poster and Artistic Reproduction] (1934-1935), for example. (Koretsky’s more famous designs were shrunk for magazine inserts and blown up for building placards.) Far more than other forms of art, the poster engaged the everyday. It assumed no literal or institutional frame. Rather, it had to stake out its own place on walls and streets, advancing on surfaces and spaces to render itself ubiquitous. In 1918

Pravda called the poster simply a “weapon.”

7

Figure 11. Anonymous, Untitled, 1940s—1950s, black-and-white photograph. [Ne boltai! Collection]

Figure 12. Viktor Koretsky, Untitled, 1940s-1950s, black-and-white photograph. [Ne boltai! Collection]

Figure 13. Moscow street, 1945. [Location unknown]

For posters were, as a medium, reproductive: not only replicative, but fertile. The constructivist Nikolai Tarabukin likened them to “condensed energy.”

8 They worked via proliferation—proliferation of form as well as of uses toward the creation of other, reworked images. Leon Trotsky urged that posters “be hanging in every workshop, every department, every office.”

9 Posters could be cut, resized, sectioned, juxtaposed with other flyers when displayed, criticized, and reproduced. Posters multiplied, covered, and were covered by other advertisements, notices, announcements. They were taken down and then rapidly replaced. They moved from place to place, shop front to factory to battlefield. Posters were lost, stolen, traded, and sold. They were exposed to wind, rain, graffiti, snow, paint, water, bullets, and fire. Posters, as objects, were witness to the pains, hardships, and dangers of life. They begat other versions of themselves. They disappeared. And were stuck up again. Posters were

in the world.

Figure 14. Music brigade on the Western Front, 1943. [Location unknown]

And yet unlike in the West, the energetic dispersal of Soviet posters arose not from phantasmagoric advertising impulses, but from duress. The repurposing that so many designs had to undergo, the hasty movement of sheets from place to place, the recombination and quotation of images old and new, did not enact the model of happy capitalist collage and its finicky exercises of choice. Rather, the creativity of the posters emerged (like everything else in the Soviet Union) from a daily struggle with the mundane. All constrained cut-and-paste, a dark bricolage shaped these designs, a process that did not render the image emancipated, multivalent, and playful, but rather put it to work—now—for the revolution. Visually stunning as they are, the power of Koretsky’s posters resides in something like a suspension of disbelief mandated by the mismatch between their relatively simple facture (wood and paint and paper) and the technological now-ness of their subjects (intercontinental missiles, fighter jets). The intensity of such posters does not derive from their capacity to prompt multiple “subjective” interpretations, but from their ability to shut down subjective interpretation itself.

Figure 15. Moscow street, 1941. [Location unknown]

V.

A source that is often invoked to explain the visual rhetoric of the Russian poster form is the lubok, a kind of illustrated broadside. The lubok was a kind of moralizing or didactic print dating to the seventeenth century. Based on folkloric drawings, it worked through hyperbolic caricature and antithesis. “Then/Now,” “Productive/Unproductive,” “Here/There,” and, most often: “We/They.” The structuring was simple—one potential condition was placed against another. The images taught by showing outcomes of good and bad, right and wrong, behavior. When Walter Benjamin saw such images posted in a Moscow factory in 1926, he likened them to comic strips. The bloated capitalists and heroic smelters everyone knows from typical communist imagery are indebted to the lubok form and its dichotomies.

Figure 16. Vladimir Mayakovsky, The Rough, Red-Haired German, 1914, colored woodblock print. [Location unknown]

Legitimizing the fledgling Soviet Union by detailing collective foes and imperialist follies, such posters created visual codes for sections of the population who previously had none: the Menshevik, the shirker, the warmonger. The encodings, in turn, supplied real-life means for those otherwise invisible sections of the population to be identified. As Stalin urged in 1933: “Look for the

kulak [prosperous peasant] we would recognize from the poster!”

10 Under Stalin, enemies were caricatured in posters using the “us/them”

lubok format. Foes were largely internal vices: wastefulness, drunkenness, intellectualism, and so on. Posters, accordingly, placed protagonist and antagonist in the same visual space. After World War II there were changes in design. Here the dual-panel, “diptych,” rose in prominence, with attention toward external situations and enemies—real and imagined—emerging as an intense preoccupation. Capitalism was visualized as being far more insidious than fascism or Menshevism ever had been.

Figure 17. Mikhail Cheremnykh, Two Worlds—Two Plans, 1949, color lithograph. [Location unknown]

Figure 18. Ukraine, 1942. [Location unknown]

Capitalism was not simply an opposing force but an alternative cosmos, characterized by degradation, warmongering, and indifference. The capitalist system was frequently pictured as a site of age, idleness, and stasis; the Soviet ambit one of youth, pedagogy, and motion. In the 1940s, for example, Koretsky began a remarkable series of posters for the Central Committee themed as

ac

ac,

ux

ux (

For us—for them). In a 1950 sheet, Soviet and Western employment conditions are contrasted via panels. At left a young male, recently hired, is shown quietly taking instruction in machine operation. An older worker and the same youth stand afront a wall plastered with postings for jobs. On the right side of the poster, meanwhile, the “American” panel: A similar worker, his hands idle, his face sullen, stares out from a nighttime scene. Capitalists (the same corpulent, top-hatted figures from the early

luboks) stride through a braying landscape of marquees, slick streets, and advertisements. Left and right here are total environments, total worlds, total plans crashed up against each other—opportunity and inequality. One might even see distinctions in clashing ideas of space: the Soviet wall of job ads at left (in a slightly larger panel) bespeaks the flat icon space of Russian art, while the perspectival city view at right is a familiar emblem for bourgeois Western consumption—not a presence, but a shallow container for vapid urban pleasures. Like the unturned fingers of Koretsky’s job seeker at right, capitalism’s injustice here intrudes into the world of language.

Figure 19. Viktor Koretsky, Untitled, 1950, poster. [Ne boltai! Collection]

In Koretsky’s poster the rustic allegorization of the lubok is individualized; lived life (equally hyperbolic) becomes the medium for the two systems’ differentiation. Such designs recall the “upside-down world” prints of sixteenth-century Germany, where popes clash with Lutheran preachers, while also stressing the urgent proximity of the “backwards” realm to a program of Soviet present-day progress.

The ostensible creed of Soviet philosophy was dialectical materialism. This mandated that one think in language, with all its paradoxes and contradictions; for language, in comparison to economics, encompassed all—it was the medium of equality. The Soviet system thus demanded that one always be concerned equally with communism and with those forces outside and hostile to it. This total dialecticism is what made Soviet philosophy far superior to “capitalist” logic, which would always be limited, and one-sided, by its telos of validity and coherence. Boris Groys has summarized the situation lucidly: “The principal demand placed on the Soviet person in the Soviet system was ... not that of Soviet thinking, but rather that of simultaneous Soviet and anti-Soviet thinking—thus that of total thought.”

11 If the Soviet system could not deliver abundance, the two-sided “dialectical” posters could at least repackage Western bounty as worthless, presenting socialism as a tolerable alternative vision to capitalism’s nightmare. By the 1960s, that nightmare, rendered grotesque, will often be the only thing left for Koretsky’s picture plane.

Figure 20. Viktor Koretsky, 4,000,000 Homeless in the USA, (4,000,000 Bezdomnikh V SSHA), 1980s, black-and-white photograph. [Ne boltai! Collection]

By then, the “evil” alternative to the Soviet utopia no longer forms one half of the poster: It is the poster. The vision of “their” duress emerges as a world unto itself. In this sense, the project of revolutionary thought, by contrast, subsists precisely in the abrogation of pluralism, in unfractured totality in the truest sense. The posters did not just lay Western evils bare; they thematized the dangers of thinking small, of not thinking only about the entire philosophical totality that was the world. In the Soviet system, one could say, what mattered was not only what posters represented but that posters were present at all, and that they kept on appearing. Posters supplied a panorama of opposites—peoples, situations, locales, at home and away—that nourished the dialectic that Soviet ideology relied upon to exist. Language, in Soviet posters, did not just speak about life, it sought to make discourse itself alive. The posters’ intensity derived from their ubiquity and their dynamic imbrication in the social, even more than what they allowed to be “seen.” During the Civil War posters were newly printed and hung in Kiev and Moscow at the rate of once a fortnight, and shipped as far as Vladivostok and Tallinn. The concurrent existence of the same image across vast expanses created a sprawling mass of viewers who could be far away from one another yet united by what they saw—a pre-“virtual” public.

vi.

Propaganda is hyperbole rendered urgent. Needing to work through caricature and visual extremism, poster artists often used types, or typecasting (tipazh), as the cultural historian Victoria Bonnell has shown. Picturing the ideal Soviet citizen and her pitiable Western counterparts mandated giving physiognomic form to dictates or caricatures. In this situation, avoiding naturalism was important; poster artists did not seek to show the world as it actually was, but selected (and exaggerated) certain features, thereby helping the viewer learn more about them. It is such tipichnost (typicality) that teaches; naturalism, undirected and unfocused, leads nowhere.

And yet portraying the Soviet model was not easy. It had little basis in contemporary life. Artists were forced to stage tomorrow’s (assumed) conditions as today’s hulking dams, soaring skyscrapers, shimmering wheatfields. The posters depicted the present in the language of an imagined future. In 1931, Anatoly Lunacharsky, Lenin’s Commissar for Enlightenment, put it like this: “Artists should not only describe what is, but should go further,

to show those forces which are not yet developed [emphasis added], in other words, from the interpretation of reality it is necessary to proceed to the disclosure of the inner essence of life, which comes out of proletarian goals and principles.”

12 The often-mocked hyperboles of Soviet realism were in no way meant to document real conditions, and viewers and artists alike knew it. They were, instead, rhetorical means to access an imminent and (for now) invisible future. Soviet posters dealt with the unpicturable—forces, sites, and industries not yet developed, “the inner essence of life.” Lunacharsky, who published on Aleksandr Pushkin and Marcel Proust, surely knew how literary “typing” offered a greater range of psychological access than “naturalism” (in the crudest sense) ever could. More than this, however, was the posters’ common reliance upon language that was almost information-free.

For Koretsky, this became a major concern in his nearly obsessive picturing of the recognizably “African victim.” To take advantage of types, he had to rely on crude, often nominally racist caricatures. For the chief aim of Koretsky’s posters was not to duplicate experience (real or imagined), but to thrust other worlds and other times before the eyes of the workaday viewer.

Figure 21. Nikolai G. Kotov, The Structure of Socialism, 1927, color lithograph. [Location unknown]

Figure 22. Viktor Koretsky, Chains Breaking—The Echo of Our Revolution! (Tsepi rvutsia—Eto otzvuk nashei revoliutsii!), 1968, poster. [Ne boltai! Collection]

Figure 23. Mozambique, Apartheid Is a Crime, 1982, three-color offset print. [UEM Graphic Division, Maputo]

The international torments described by Koretsky in this exhibition imagine the power of suffering to resonate in many different forms. These works rarely employed appropriated images of real horrors, such as photographs or newspaper excerpts from actual incidents, as did much propaganda produced in Africa.

13 Instead Koretsky relied upon blunt, often disturbing

tipazh-based models who were posed specifically for his maquettes. That the suffering they indexed could not be pinned down to a specific time or place made them all the more compelling; unmoored from a real event, their depicted struggles became the struggles of an entire communist world in the making.

Yet this was not just simple psychology, a simple response. The “image of suffering” in the late USSR disavowed purely personal visual experience, to demand quiet involvement in a larger world of shared sacrifice that was beyond the reach of simple sight. In its publicness and its virtually limitless replicative potential, the poster implied that this struggle for the as-yet-unseen was constantly being renewed. It saturated Soviet life with the invisible, using the language of the crassly commercial. Pavel Florensky put it like this: “Life in the visible world alternates with life in the invisible, and thus we experience moments . . . when the two worlds grow so very near in us that we can see their intimate touching . . . we can sense that the invisible world (still unearthly, still invisible) is

breathing.”

14 Koretsky—whose art, too, always spoke as a “we”—imagined what were for most Soviet viewers unseen conditions, and that is what made them legitimate and unique within the late Soviet lifeworld.

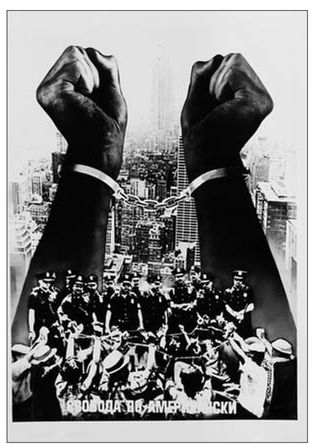

Figure 24. Viktor Koretsky, Freedom American-Style (Svoboda po-Amerikanski), ca. 1980s, black-and-white photograph. [Ne boltai! Collection]

As Soviet visual culture mobilized feeling for others as an obviation of the self, it asked not just for identification, but for a kind of socialized empathy. This was an empathy based on paradox. The immediate, bored, hungry, and freezing reality of a poster viewer was made to be nothing nearly as urgent as the dangers facing far-off others. Images, as they always had, personalized spectacular strife; Koretsky’s vision made that old rhetoric new, domesticating distant struggles as a moment in all of our lives. “For who would see a man represented in colors and struggling for truth, disdaining fire,” wrote the Byzantine Ignatios, “and would not be drenched in warm tears and groan?”

15

Figure 25. Viktor Koretsky, Africa Fights, Africa Will Win! (Afrika boretsia, Afrika pobedit!), 1968, poster. [Ne boltai! Collection]

sources

Walter Benjamin’s comments on Russian posters (1926-1927) are in “Moscow Diary,” October 35 (1986): 56, 78. H.G. Wells describes similar postings (and his own audience with Lenin) in his Russia in the Shadows (London, 1920).

Malevich’s words on Russian avant-garde painting and Byzantine icons are transcribed in John Milner, Vladimir Tatlin and the Russian Avant-Garde (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1983), 240. Mayakovsky’s words on posters as “bulletins” appear in Renate Kummer, Nicht mit Gewehren, sondern mit Plakaten wurde der Feind geschlagen! Eine semiotisch-linguistische Analyse der Agitationsplakate der russischen Telegrafenagentur ROSTA (Bern and New York: Peter Lang, 2006), 12.

On the general history of posters, see Max Gallo, The Poster in History (NewYork,1979); Alain Weill, The Poster (Boston, 1985). On early printed propaganda in central Europe, particularly in the Holy Roman Empire: Hermann Wascher, Das deutsche illustrierte Flugblatt, 2 vols., (Dresden, 1955); R. Schenda, “Die deutschen Prodigensammlungen des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts,” Archiv für Geschichte des Buchwesens 4 (1963): 638-710; and Wolfgang Harms and Michael Schilling, eds., Das illustrierte Flugblatt der frühen Neuzeit (Stuttgart, 2008), esp. 85-122. Of the colossal literature on Russian posters, crucial to this essay has been Klaus Waschik and Nina Baburina, Werben für die Utopie: Russische Plakatkunst des 20. Jahrhunderts (Bietigheim, 2003); Frank Kämpfer, “Der Rote Keil”: Das politische Plakat, Theorie und Geschichte (Berlin, 1985); and Victoria Bonnell, The Iconography of Power (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999). It has also benefited from Leah Dickerman, ed., Building the Collective: Soviet Graphic Design 1917—1937 (New York, 1996). On the lubok tradition:

Alla Sytova, The Lubok: Russian Folk Pictures (Leningrad, 1984). On the ROSTA windows, which first appeared in Moscow in 1919 with the art of Mikhail Cheremnykh and most famously V. V. Mayakovsky, see Peter N. Kenez, The Birth of the Propaganda State (New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 115-18. On paper propaganda in Africa, see Berit Sahlström, Political Posters in Ethiopia and Mozambique (Uppsala: Almqvist and Wiksell, 1990).

On Orthodox image theory: Robin Cormack, Painting the Soul: Icons, Death Masks and Shrouds (London, 1997); Clemena Antonova, “Florensky’s ‘Reverse Time’ and Bakhtin’s ‘Chronotype’: A Russian Contribution to the Theory of the Visual Arts,” Slovo 15.2 (Autumn 2003): 104. On icons and empathy, Arne Effenberger, “Images of Personal Devotion: Miniature Mosaic and Steatite Icons,” in Byzantium: Faith and Power (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004), 209-15. On the icon as an operation rather than a form: Jefferson Gattrall and Douglas Greenfield, eds., Alter Icons: The Russian Icon and Modernity (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2010). Premodern imaginings of suffering are discussed in Mitchell B. Merback, The Thief, the Cross, and the Wheel: Pain and the Spectacle of Punishment in Medieval and Early Modern Europe (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1998).

On Soviet word and image relations: Yury Lotman, “Painting and the Language of Theatre: Notes on the Problem of Iconic Rhetoric,” in Tekstura, trans. and ed. Alla Efimova and Lev Manovich (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 45-55. On Bolshevik time and space: Christer Pursiainen, “Space, Time, and the Russian Idea,” in Beyond the Limits: The Concept of Space in Russian History and Culture, ed. Jeremy Smith (Helsinki, 1999), 71-94. On tipichnost, see Ralph E. Matlaw, ed., Belinsky, Chernyshevsky, and Dobrolyubov, Selected Criticism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1962), 3-82.

Agit-trains are exhaustively discussed in Richard Taylor, “A Medium for the Masses: Agitation in the Soviet Civil War,” Soviet Studies 22.4 (April 1971): 562-74.

Early ideas about pre-“virtual” communities of readers appear in Gabriel Tarde, “The Public and the Crowd,” in On Communication and Social Influence (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969), 277—94.

This essay’s thinking about paradox and language is much indebted to Boris Groys, The Communist Postscript, trans. Thomas H. Ford (New York: Verso, 2010).

a

a a

a derives from the German Plakat, literally meaning to post up, which itself comes from the old Dutch verb aanplakken (to stick or place over). And it was from German and Dutch middle-class broadsheet culture of earlier centuries that Russian notions of mass-produced postings seem to have arisen.

derives from the German Plakat, literally meaning to post up, which itself comes from the old Dutch verb aanplakken (to stick or place over). And it was from German and Dutch middle-class broadsheet culture of earlier centuries that Russian notions of mass-produced postings seem to have arisen.

y

y ∂e

∂e ue), a jolt that rouses one’s attention to reality itself.”6 Soviet images rendered this arousal revolutionary. One need only think of how the earliest posters mounted in Moscow by the Bolsheviks during the Civil War were themselves “windows” (okna ROSTA [Russian Telegraph Agency]), large stenciled posters illustrating party policy or economic news placed over abandoned shop fronts beginning in 1919. Intended to supplant the barren, tawdry (and, at the time, empty) “spaces” of consumption with flat, brilliant, unrelenting walls of pedagogy, the ROSTA windows instructed readers, with rhyming couplets and schematic illustrations, how to sort potatoes, where to pay their taxes, why they should obtain a smallpox inoculation. The messages changed from day to day. In Moscow lithography was used, but in Odessa paper was so scarce that the designs were transferred to plywood, displayed for a day, and then painted over with the most current news. Compositionally these images aimed to turn the “lie of bourgeois perspectivism”—the “sated gaze”—in on itself. The okna were the silent, Orthodox iconostasis transformed into a working rostrum—a fitting metaphor for the Revolution itself.

ue), a jolt that rouses one’s attention to reality itself.”6 Soviet images rendered this arousal revolutionary. One need only think of how the earliest posters mounted in Moscow by the Bolsheviks during the Civil War were themselves “windows” (okna ROSTA [Russian Telegraph Agency]), large stenciled posters illustrating party policy or economic news placed over abandoned shop fronts beginning in 1919. Intended to supplant the barren, tawdry (and, at the time, empty) “spaces” of consumption with flat, brilliant, unrelenting walls of pedagogy, the ROSTA windows instructed readers, with rhyming couplets and schematic illustrations, how to sort potatoes, where to pay their taxes, why they should obtain a smallpox inoculation. The messages changed from day to day. In Moscow lithography was used, but in Odessa paper was so scarce that the designs were transferred to plywood, displayed for a day, and then painted over with the most current news. Compositionally these images aimed to turn the “lie of bourgeois perspectivism”—the “sated gaze”—in on itself. The okna were the silent, Orthodox iconostasis transformed into a working rostrum—a fitting metaphor for the Revolution itself.

ac,

ac,

ux (For us—for them). In a 1950 sheet, Soviet and Western employment conditions are contrasted via panels. At left a young male, recently hired, is shown quietly taking instruction in machine operation. An older worker and the same youth stand afront a wall plastered with postings for jobs. On the right side of the poster, meanwhile, the “American” panel: A similar worker, his hands idle, his face sullen, stares out from a nighttime scene. Capitalists (the same corpulent, top-hatted figures from the early luboks) stride through a braying landscape of marquees, slick streets, and advertisements. Left and right here are total environments, total worlds, total plans crashed up against each other—opportunity and inequality. One might even see distinctions in clashing ideas of space: the Soviet wall of job ads at left (in a slightly larger panel) bespeaks the flat icon space of Russian art, while the perspectival city view at right is a familiar emblem for bourgeois Western consumption—not a presence, but a shallow container for vapid urban pleasures. Like the unturned fingers of Koretsky’s job seeker at right, capitalism’s injustice here intrudes into the world of language.

ux (For us—for them). In a 1950 sheet, Soviet and Western employment conditions are contrasted via panels. At left a young male, recently hired, is shown quietly taking instruction in machine operation. An older worker and the same youth stand afront a wall plastered with postings for jobs. On the right side of the poster, meanwhile, the “American” panel: A similar worker, his hands idle, his face sullen, stares out from a nighttime scene. Capitalists (the same corpulent, top-hatted figures from the early luboks) stride through a braying landscape of marquees, slick streets, and advertisements. Left and right here are total environments, total worlds, total plans crashed up against each other—opportunity and inequality. One might even see distinctions in clashing ideas of space: the Soviet wall of job ads at left (in a slightly larger panel) bespeaks the flat icon space of Russian art, while the perspectival city view at right is a familiar emblem for bourgeois Western consumption—not a presence, but a shallow container for vapid urban pleasures. Like the unturned fingers of Koretsky’s job seeker at right, capitalism’s injustice here intrudes into the world of language.