rewind, fast forward, play

With Africans, music and rhythm are not luxuries but part and parcel of their way of communication. Any suffering we experienced was made much more real by song and rhythm.

The most powerful form of resistance in South Africa was the refusal of blacks to remain prisoners in their own land. This struggle for freedom begins when Portuguese seafarers first reach the South African coastline in the early 1500s. Dutch settlers follow in 1652. Cattle raids and land grabs ensue. Dutch colonial authorities appropriate land and allot farms to white settlers, displacing the locals. Over time, this encroachment leads to the enslavement of black people as servants.

Frontier wars break out between the settlers and black ethnic groups such as Xhosa and Zulu. Although better equipped with guns and horses, the settlers cannot quell resistance. One strategy adopted by the Zulu warriors was to collectively chant before going into battle as a way of instilling fear in the enemy. This performance makes the settlers more vulnerable to attack. The strategy endures in popular memory.

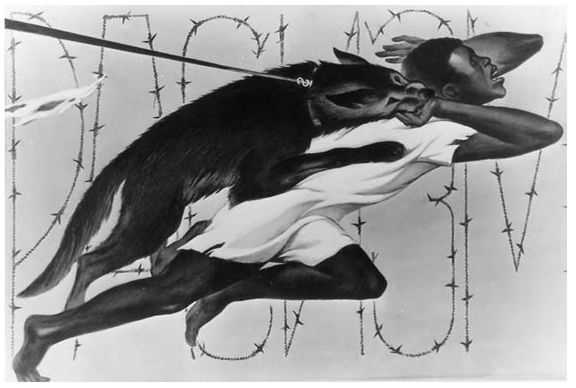

Figure 57. Viktor Koretsky, Africa Shall Be Free! (Afrika budet svobodnoi!), 1960, poster. [Ne boltai! Collection]

Diamonds and gold are discovered in 1867 and 1886, respectively. South Africa becomes an industrial giant. A huge percentage of the world’s wealth passes through the hands of black laborers in the mines. Local governments implement new laws to prevent blacks from owning land, and they force blacks onto “homelands” where they reside under impoverished conditions.

2 African men migrate to the cities to find wage-paying jobs.

The twentieth century: living in squalid, single-sex hostel compounds—just to pay colonial taxes and survive—workers compose songs, reflecting on this new urban experience. Away from loved ones and the familiarity of home, the men sing about the precarious lifestyle in the mines and the lonely existence in the city. Most of the songs are performed for entertainment. They assert ethnic identity. They address rural life and celebrate African heroes while also condemning the deterioration of traditional values and the rise of apartheid policies.

When performed, these songs are accompanied by light-footed dancing, a product of overcrowded compounds, earning them the name

Isicathamiya, or “to walk on one’s toes.”

3 Beyond the mines and in the townships, new musical styles develop such as Marabi, Kwela, and Mbaqanga, as influences from America appear, such as ragtime.

4 The music’s form and content express socioeconomic conditions, the hardships and dangers of urban life in the townships. This music uses instruments and is performed for audiences in clubs and stadiums. Artists like Miriam Makeba become outspoken opponents of apartheid internationally. Songs such as her

Iphi Ndlela (Where Is the Way) distill these early musical traditions and move them forward.

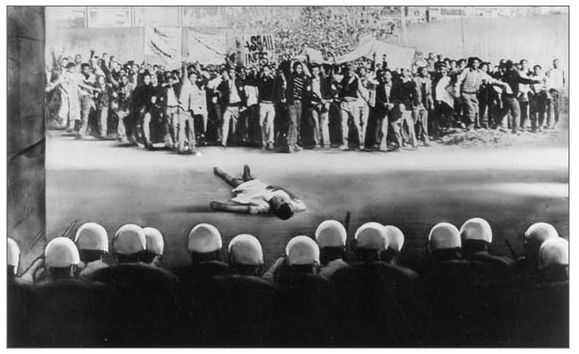

Figure 58. Viktor Koretsky, Smash the RSA! (Republic of South Africa) (Sokrushit! IuAR), 1970s, black-and-white photograph. [Ne boltai! Collection]

In 1897, Enoch M. Sontonga writes and composes

Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika (God Bless Africa), the most venerable of all protest songs. Originally arranged as a blessing, it offers a plea for African unity. It is popularized by the African National Congress (ANC) and later adopted as the organization’s anthem.

5 In 1923, the ANC begins a full-scale national liberation movement against the white government, challenging the state’s repressive laws by organizing civil disobedience. Violent clashes spread throughout the country.

Different stages in the protest demand different strategies: boycotts, strikes, marches. Songs decry the plight of black people and become more explicit, challenging the status quo. Engines for mass democratic solidarity, the songs are rooted in oral history, sung or chanted collectively; they welcome improvisation. The songs often describe current events.

Racial segregation becomes official in 1948 as apartheid. Laws favor whites and oppress the black population. Despite these conditions, black South Africans find ways to resist peacefully. They use music as a vehicle for uniting diverse ethnicities across distances and generations. Soon, Radio Freedom, the voice of the African National Congress, broadcasts from Tanzania, Zambia, Angola, and Ethiopia. Live broadcasts send messages directly to the public. Radio Freedom keeps the ANC active in the popular imagination, even though black listeners live under threat of imprisonment just for tuning in.

The trademark introduction of Radio Freedom? Machine-gun fire. Followed by these words: “This is Radio

Freedom, the voice of the African National Congress and its military wing

Umkhonto we Sizwe.” Exiles broadcast messages of comfort and hope to encourage resistance and maintain ties with family and friends. Songs such as

Shaya maBunu (

Fight the Boers) and

Pasopa Nantsi ‘

Ndodemnyama Verwoerd (Watch Out Verwoerd, Here Comes the Black Man) boldly and derisively challenge the white government.

6 Other songs, such as

Senzeni Na? (What Have We Done?), express pain and existential despair. They mourn the loss of loved ones and speak to the intolerable conditions of life under apartheid. They raise awareness, build solidarity, and motivate communities into mass action.

Figure 59. Viktor Koretsky, South Africa. Angola. Racism in Action (IuAR. Angola. Rasizm v deistvii), ca. 1970s, black-and-white photograph. [Ne boltai! Collection]

Apartheid grows more aggressive; protest songs grow more combative. In 1956, under the banner of the Federation of South African Women (FEDSAW), a multiracial wave of twenty thousand women marches on the Union Buildings in Pretoria to protest the extension of the pass law to women.

7 The song

Wathint’ abafazi,

wathint’ imbokodo (

You Have Struck a Woman, You Have Struck a Rock) can be heard in the streets. This show of force brings issues of racial injustice to much greater public attention.

Many protest songs derive their musical structures and rhythms from Christian hymns. Made up of short repetitive verses, as in Senzeni Na? (What Have We Done?), song elements are repeated in different harmonies, enhanced with improvisational clapping and dancing. Invoking pain and tragedy, Thula Sizwe (Quiet and Listen) questions the shaping of tomorrow’s world.

| Thula Sizwe | (Quiet and Listen) |

|---|

| Thula Sizwe | (Quiet and Listen) |

| Ungabokala | (Do Not Cry) |

| Ujehova Wakho | (Our God) |

| Uzokunqobela | (Will Protect Us) |

| |

| Inkululeko | (Freedom) |

| Sizoyithola | (We Will Get It) |

| Ujehova Wakho | (Our God) |

| Uzokunqobela | (Will Protect Us) |

Camouflaged by their hymnlike praises, the lyrics feed the African listener double entendres that avoid state censorship. Adaptable to almost any new exigency, lyrics change as the political situation does. Over time, new lines, new words, new meanings are created. A song such as

Somlandela uJesu (

We Will Follow Jesus) transforms into

Somlandela uLuthuli (We Will Follow Luthuli), as the singers communicate indirect political speech.

8 The South African Security Branch is suspicious, but they do not understand the coded languages embedded in such songs, and do not ban them.

Undeterred by police violence, activism grows. Resistance expands beyond pass laws to include rent boycotts and protests against forced land removals. Prompted by the Sophiatown evictions of 1955 and the bus boycott two years later in Alexandra,

Asibadali (We Won’t Pay Rent) and Azikwela (We Won’t Ride) become rallying anthems.

9

Figure 60. Viktor Koretsky, Racism (Rasizm), 1970s, black-and-white photograph. [Ne boltai! Collection]

Sharpeville, 1960. A turning point in the liberation struggle. South African police open fire on peaceful protestors, killing sixty-nine people and wounding hundreds. The incident exposes the naked brutality of police and instills fear of retaliation across white communities. In response, after decades of nonviolent protest, the ANC abandons this policy and establishes a military wing known as

Umkhonto we Sizwe, or MK (Spear of the Nation). In his Rivonia Trial speech, Nelson Mandela explains, “Fifty years of nonviolence had brought the African people nothing but more and more repressive action, and fewer and fewer rights.”

10 Concluding that violence must be met with violence, the ANC enters a new era in the struggle for freedom.

Self-exile of the ANC leadership to avoid arrest. The banning of all anti-apartheid organizations. Martial law.

A leadership void appears. Young people take up the struggle, keeping it alive. On the streets, Toyi-toyi, a vigorous chant—often punctuated by the rallying cry of Amandla! (Power!), to which the people respond, Ngawethu! (Is Ours!)—becomes an important crystallizing gesture. Originating in Zimbabwe, this chant is accompanied by a foot-stomping dance that mimics guerilla warfare. When Toyi-toyi breaks out on the streets, security forces get nervous.

Figure 61. Viktor Koretsky, USA. Republic of South Africa. World Policeman (from the series “The Bloody Business of Imperialism”) (SShA. IuAR. Mirovoi zhandarm [from the series “Krovavye dela imperializma”]), ca. 1970s, black-and-white photograph. [Ne boltai! Collection]

Other melodies are deeply sorrowful. They mourn the deaths of so many young people in the service of the struggle. Rarely credited to a single composer, such songs are imagined to express the feeling of an entire community—even when the individual composer is known, as in the case of one of the most famous protest songs, PasopaNantsi ‘Ndodemnyama Verwoerd (Watch Out Verwoerd, Here Comes the Black Man), written by Vuyisile Mini, a member of Umkhonto we Sizwe.

Figure 62. Viktor Koretsky, Profession: Mercenary, Murderer from the Republic of South Africa (Professiia: Naemnik, Ubiitsa iz IuAR), ca. 1970s, black-and-white photograph. [Ne boltai! Collection]

Fellow inmates hear Mini singing

Pasopa Nantsi in defiance while being led to his execution.

11On 16 June 1976, youth from Soweto schools organize a peaceful march in protest against the use of the Afrikaans language as the medium of instruction in African schools. They assemble at points throughout Soweto, then set off to meet at a central location, where they plan to pledge their solidarity and sing Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika. This is not to be. Throughout the month of June, police repeatedly open fire on students, killing more than two hundred and wounding many more. These events spark countrywide protests that lead to hundreds more fatalities and thousands of wounded. This massacre changes the political landscape by bringing youth activity to the forefront of the movement. Students’ anger, frustration, and impatience fuel running confrontations with the police. Antagonism between the groups becomes more intense. Officers sometimes shoot at random. More people escape into exile.

Fury and fearlessness galvanize the community. Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation) and Shona Malanga (Gone Are the Days) are sung in solidarity. Funerals become more commonplace; songs such as Hamba Kahle Umkhonto (Safe Journey Spear) are chanted in commemoration of the fallen.

Figure 63. Viktor Koretsky, Soweto. Law and Order (from the series “The Bloody Business of Imperialism”) (Soueto. Sila i pravo [from the series “Krovavye dela imperializma]), 1970s, black-and-white photograph. [Ne boltai! Collection]

| Hamba Kahle Umkhonto | (Safe Journey Spear) |

|---|

| Wemkhonto | (Yes Spear) |

| Umkhonto we Sizwe | (Spear of the Nation) |

| Thina Bantu Bomkhonto Sizímisele | (We, the Members of Umkhonto, Are Determined) |

| Ukuwabulala | (To Kill) |

| Wona Lamabhunu | (These Boers)12 |

In the 1980s, townships become hotbeds for open revolution as thousands of young recruits leave for neighboring countries in search of military training. The ANC together with other anti-apartheid organizations embarks on a mass action campaign of civil disobedience. Taking to the streets, urging the public to act, breaking the barrier of fear that had kept them silenced, people sing together in public. Such displays of power define a spatial freedom necessary for the growth and survival of the movement. Singing encourages direct participation. Singing spreads the message of defiance.

Such actions eventually lead to the release of Nelson Mandela and the lifting of the ban on the ANC and other political organizations. A process of negotiation begins with the apartheid government, which ultimately leads to adoption of a fully democratic constitution in 1994.

Today, the struggle against economic oppression endures in South Africa. Over a decade and a half after the end of apartheid, many South Africans still feel that they have not benefited from economic growth. Poor communities mobilize increasingly to challenge the government. Drawing inspiration from the long tradition of mass action protests, such groups use songs to inform, influence, and instigate. Making use of both legal and illegal actions as a means to build power, a new wave of resistance seeks not only to force policy changes but also to alter the mind-set of the government administration, to return the movement to its roots, to the “bottom-up” approach so effective during the struggle years. With increasing unemployment, housing shortages, poor health care, and widespread crime, ordinary South Africans are once more open to appeals for radical transformation. The success of this potentially new revolution seems to require the rekindling of cultural expressions linked to those used during the struggle against apartheid. Slogans such as Injury to One Is an Injury to All and Mayibuye iAfrica (Come Back Africa) still resonate strongly among many black South Africans.

In this context, the 2008 appointment of Jacob Zuma as president of South Africa signals a deliberate move away from the neoliberal policies championed by his predecessor, Thabo Mbeki. Clearly, Zuma’s popularity among union members and the young derives not only from his overhauling of economic priorities, but also from his reputation as a former member of Umkhonto we Sizwe, his modest family background, and, most distinctive of all, his prominent use of song as a political tool.

His trademark chant

Umshini Wami (Bring My Machine Gun)—which he performs often and with visible relish—transforms Zuma’s singing and dancing body into a potent image of the oppressed taking power. Benefiting from mass media’s exceptional ability to burnish his image as an anti-elitist and a committed socialist, Zuma emphasizes the importance of historical context as the key to understanding

Umshini Wami’s continued relevance in post-apartheid South Africa. Although critics complain that the song incites violence, Zuma speaks of the machine gun’s metaphorical significance, its status as a symbol of popular access to the machinery of power.

13| Umshini Wami | (Bring My Machine Gun) |

|---|

| Umshini Wami Mshini Wami | (My Machine My Machine) |

| Khawuleth‘umshini Wami | (Please Bring My Machine) |

| Umshini Wami Mshini Wami | (My Machine My Machine) |

| Khawuleth’umshini Wami | (Please Bring My Machine) |

| Umshini Wami Mshini Wami | (My Machine My Machine) |

| Khawuleth‘umshini Wami | (Please Bring My Machine) |

| Khawuleth’umshini Wami | (Please Bring My Machine) |

| Wen’uyang’ibambezela | (You’re Holding Me Back) |

| Umshini Wami, Khawuleth’umshini | (My Machine, Please Bring My Machine) |

| Wami | |

This machine gun that announces the broadcasts of Radio Freedom, this machine gun that Jacob Zuma sings about at his political rallies, this machine gun is not just any rifle. It is a particular weapon. It is on the coat of arms of Zimbabwe and the national flag of Mozambique; such has been its crucial role in liberation struggles across Africa and around the world. It was designed and manufactured with such skill that this weapon is now famous for never jamming, for being inexpensive to maintain, and for being the ideal weapon for arduous physical conditions. This weapon that Zuma sings about was originally produced far away from South Africa in the giant workshops in the Russian city of Izhevsk by Soviet workers. It is the AK-47, and it is widely regarded as the most effective object ever to leave a Soviet factory floor.

14 No doubt the workers who made the AK-47 were surrounded by state propaganda, and one cannot help but wonder if Viktor Koretsky’s images of suffering and survival, his emotional calls for solidarity with the downtrodden, did not play some role in turning a death-dealing machine into one of Africa’s most potent symbols of an empowered life.

sources

On apartheid, South Africa, and music, see the essays in Steve Biko, I Write What I Like: Selected Writings (Oxford: Heinemann, 1987); Anne-Marie Gray, “Liberation Songs Sung by Black South Africans During the Twentieth Century,” International Journal of Music Education (1999): 30-36; Grant Olwage, Composing Apartheid: Music for and Against Apartheid (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 2008); and Lee Hirsch’s film Amandla! A Revolution in Four-Part Harmony (New York: Artisan Entertainment, 2002).

On resistance and song in the twentieth century, see Guy Carawan and Candie Carawan, eds., Sing for Freedom: The Story of the Civil Rights Movement Through Its Song (Bethlehem, PA: Sing Out, 1990); Ajay Heble and Daniel Fischlin, Rebel Music: Human Rights, Resistant Sounds and the Politics of Music Making (Montreal: Black Rose Books, 2003); and Angela M. Nelson, ed., This Is How We Flow: Rhythm in Black Cultures (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1999).

On the historical background of modern South Africa, Nelson Mandela’s Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1994) captures the era in one accessible volume.