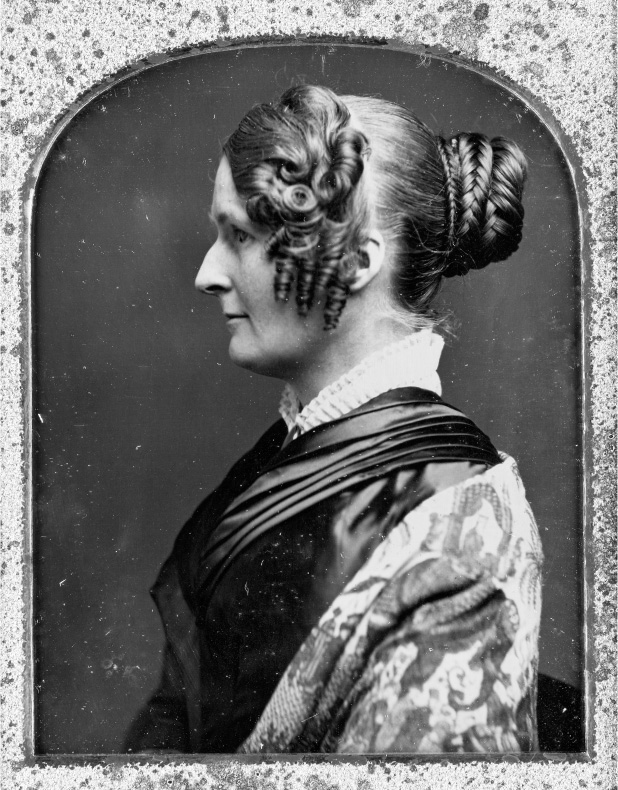

Maria Weston Chapman, c. 1846. Daguerreotype.

He would not become soft. It was exhaustion he wanted—it helped him write. He needed each of his words to appreciate the weight they bore. He felt like he was lifting them and then letting them drop to the end of his fingers, dragging his muscle to work, carving his mind open with idea.

—COLUM MCCANN, TRANSATLANTIC, 2013, IMAGINING DOUGLASS MEDITATING IN PRIVATE, JUST AFTER HIS ARRIVAL IN IRELAND, FALL 1845

The publication of Douglass’s Narrative made him in time the most famous black person in the world. Fame had its uses; but he possessed deeper aims both as an abolitionist and as a thinker. He continued to all but mystify himself, much less the audiences he addressed. In late 1844, in a note accompanying the draft of his first article for publication other than in a newspaper, Douglass mused with wonder, “I looked exceedingly strange in my own eyes as I sat writing. The thought of writing for a book!—and only six years since a fugitive from a Southern cornfield—caused a singular jingle in my mind.”1 The Narrative soon caused an extraordinary literary jingle in the United States; words had now become for him a source of magic, truth, influence, and power.

The May 9, 1845, issue of the Liberator carried news of the publication of Douglass’s Narrative. It also contained verbatim the preface written for the book by Garrison, as well as a note about Wendell Phillips’s letter of endorsement, also published with the volume. Both Garrison and Phillips prominently mentioned Douglass’s marvelous white “sailing ships” metaphor, his teenage vision of freedom while gazing at Chesapeake Bay, from the text. They both seemed to realize they had just read something quite unprecedented in slave narratives, and in American literature more broadly. They had encountered a writer, although they could not resist portraying him as the necessary exhibit of the cause. Garrison wrote about Douglass with great admiration and a mentor’s pride; Garrison also left him saddled with the highest symbolic expectations: to continue to be “an ornament to society and a blessing to his race.” Phillips openly worried for Douglass’s safety as a fugitive, since he had now revealed so completely his identity to the world. The Boston Brahmin radical, though, also placed Douglass in high company. Referring to Aesop’s fable of “The Man and the Lion,” Phillips asked Douglass to remember when “the lion complained that he should not be so misrepresented ‘when the lions write history.’ I am glad the time has come when the ‘lions write history.’ We have been left long enough to gather the character of slavery from the involuntary evidence of the masters.”2

Soon the young lion, with armloads of his history, would be off to Britain and Ireland telling his story. The book became an instant success, selling five thousand copies in the first four months. By the end of 1847, after Douglass’s twenty-month tour of the British Isles, the bestseller had gone through nine editions and sold eleven thousand copies. And by 1860, it had sold thirty thousand and been translated into French and German. As Douglass prepared for his journey to England, his book came out in a paper edition, sold at twenty-five cents apiece, or $2.75 per dozen.3

• • •

On Friday evening, August 15, 1845, at the large Lyceum Hall in Lynn, a “Great gathering” assembled to bid farewell to Douglass, to local abolitionist James Buffum, who was to be the black activist’s traveling companion, and to Lynn’s own Hutchinson Family Singers. Asa, John, Judson, and Abby Hutchinson sang to the throng in “their inimitable strains,” an observer reported. Douglass spoke words of farewell, as he had also done two days earlier in his first Northern hometown of New Bedford. The meeting passed resolutions, especially a favorite-son message to Douglass of deep respect and best wishes in his journey to “the shores of the Old World.” Buffum was a Lynn neighbor, a former Quaker who had become a militant Garrisonian radical, who now used his considerable fortune gained as a carpenter, house contractor, and financier to aid the abolitionist cause.4

The press did not report whether Anna and the three children attended, but they must have been at the young departing hero’s side for this meeting. Rosetta was six years old, Lewis almost five, and Frederick Jr. almost three and a half as they watched their father depart now to travel across the sea. These countless leave-takings were now vivid childhood memories; over time they likely had felt, consciously or not, like abandonments, even as the children would convert the story into respectful honor toward their famous father and his cause. The ten-month-old Charles would not remember this one, but would recollect many more leavings and comings later in life. For Anna the farewell celebration of her husband must have resurrected the fears she harbored on the day Frederick fled Baltimore as she agonizingly awaited word of his safety and the message to join him after his escape. But this time he would be gone a year or more, she would not be joining him, and she was left to fend for herself, to care for the brood of little Douglasses, and to rely on their white abolitionist friends for financial assistance. We can only imagine Anna’s stoic courage, when they embraced good-bye, and when he lifted each child in his arms—what future could the young hero promise them? Could he truly write and speak his way into an international antislavery universe in such a way as to provide for their future, as well as change the world? Was it possible that a voice was enough to build a family, a career, and some part of a new history? Anna had likely already reached a stage in their difficult but powerful bond where it simply was hers to do and not to ask why.

The day after the Lynn gathering, Douglass, Buffum, and the Hutchinsons boarded the Cambria, the great new 219-foot, wooden side-wheeler steamship of 1,422 tons on the Cunard Line, and were off on their eleven-day voyage to England. On that Saturday afternoon, a crowd of abolitionist well-wishers gathered on the Boston docks. The Hutchinsons “sang a song at parting in the time of ‘Cranbambuli,’ ” wrote Asa in his journal, “in which we bid farewell to New England.” The crowd onshore “bid adieu” by swinging hats and handkerchiefs, to which all the passengers responded with shouts and “copious gushing tears.” The Cambria sailed first to Halifax, Nova Scotia, where they were met by the firing of cannons, then crossed the Atlantic to the port of Liverpool, encountering en route many three-masted ships as well as ominous icebergs. Douglass had experienced the waves of the Chesapeake, but this first encounter with the rhythms of the open North Atlantic may have even included a game of billiards or shuffleboard with the Hutchinsons. The Cambria, which had made its maiden Atlantic voyage only a year earlier and was the fastest commercial passenger steamer afloat, rode the waves like “a wild sea gull,” reported Asa Hutchinson. Within a few days most of the passengers suffered from seasickness.5

Despite Buffum’s attempt to buy first-class-cabin accommodations, the ship’s captain, Charles Judkins, assigned the two abolitionists to steerage belowdecks. Douglass had faced Jim Crow’s ugly ways more times than he could count, but now, on his first ocean voyage and after such a joyous send-off among friends, this episode probably stung more than he let on, even as it also became so publicly useful. Douglass was content in steerage, he recollected, because the Hutchinsons came to visit frequently, singing at his “rude forecastle-deck,” keeping it alive with “music . . . and with spirited conversation.”6 Somewhere in relatively calm seas, a day or so before the arrival at Liverpool, though, another kind of storm brewed when Douglass and his abolitionist friends tried to stage an antislavery meeting at the saloon on the main deck.

The passengers of the Cambria were a multinational, multiracial, multireligious lot, a veritable sampling of the world and of America strewn together and sifted in the confined spaces of a ship at sea. Like the crew of Melville’s Pequod in Moby-Dick, what Andrew Delbanco called “a dazzling array of human types . . . taking turns in a stage play,” Douglass wrote in similar terms about his shipmates in a public letter back to Garrison. Ever the storyteller, Douglass described the Cambria as a “theater” with “all sorts of people, from different countries, of the most opposite modes of thinking on all subjects.” Flung together, some of the Cambria’s diverse human cargo mixed well and some did not. She mingled the “scheming Connecticut wooden clock-maker, the large, surly, New York lion-tamer, the solemn Roman Catholic bishop, and the Orthodox Quaker.” Also shipping to Liverpool were a “minister of the Free Church of Scotland, and a minister of the Church of England—the established Christian and the wandering Jew, the Whig and the Democrat, the white and the black.” This cast could have become a comedy or a tragedy in the right hands. The “dark-visaged Spaniard and the light-visaged Englishman—the man from Montreal and the man from Mexico” had also boarded at New York or Boston. But if politics and religion might at least be somehow bridged for eleven days, a larger problem emerged because of the “slaveholders from Cuba, and slaveholders from Georgia.” Douglass warmed to the irony. “We had antislavery singing,” he wrote, “and proslavery grumbling, and at the same time that Governor Hammond’s Letters [James Henry Hammond, governor of South Carolina] were being read, my Narrative was being circulated.”7 Here was America’s greatest problem—slavery—festering on board a steamship about to land in Britain’s former largest slave-trading port.

In this volatile mix Douglass accepted the invitation of the captain himself to deliver a speech. Before he had uttered a few sentences, what he called the “salt water mobocrats,” led by a Mr. Hazzard of Connecticut, shouted him down with fists clenched in the air. “That’s a lie!” bellowed his opponents as Douglass attempted a discourse on the conditions of slaves in America. Douglass kept trying to be heard over the hecklers, finally resorting to “reading a few extracts from slave laws.” But the gathering deteriorated into near violence, as a Cuban shouted, “I wish I had you in Cuba!,” and the Georgian, “I wish I had him in Savannah! We would use him up!” With these men rushing toward Douglass and threatening to throw him overboard, an Irishman as well as Captain Judkins came to Douglass’s defense. The captain ended the melee by threatening to put the mob leaders “in irons.” The proslavery thugs, with brandy cups in hand, scattered to other corners of the ship, and as Douglass remembered, “conducted themselves very decorously” for the remainder of the voyage.8

But they had performed their service to the cause, and after landing in Liverpool, did so even more. The Georgian and the Cuban, and perhaps other allies from aboard the Cambria, went to the British press to defend themselves and, in so doing, Douglass maintained, provided the black abolitionist “a sort of national announcement of my arrival in England.”9 Much sympathy came Douglass’s way as news of his discriminatory treatment spread through reformist England and Ireland.

Douglass had attempted his speech on the main deck, with the Irish highlands within view. The next day, August 28, the Cambria steamed into the river Mersey and to the great quays of Liverpool. Douglass and Buffum spent a mere two days or so with their feet on the ground in the city, then were off on the ferry to Dublin across the Irish Sea. They took up residence at the home of Irishman James A. Webb, brother of the printer Richard D. Webb, both staunch supporters of abolition and temperance. At first the Webbs, especially Richard and his wife, Hannah, were generously hospitable hosts, although that relationship would sour over time. Bald and bespectacled, with a full white beard in Quaker style, Richard Webb was an astute businessman and a loyal Garrisonian with strong ties to Maria Weston Chapman; together with her at the helm in Boston, Webb took on a role as Douglass’s manager. By mid-September Douglass reported that he had delivered numerous lectures to overflow crowds, at the Royal Exchange (now City Hall), at a Friends’ meetinghouse, the Music Hall, and even one to the inmates at a local prison. Undergoing a personal awakening, he seemed especially astonished that he encountered no “manifestations of prejudice.” He traveled on all conveyances and “was not treated as a color, but as a man.”10

Douglass quickly found comfort on Irish soil, except with Webb himself. His host simply did not like Douglass’s personality, calling him “absurdly haughty, self-possessed, and prone to take offense.” Webb thought Douglass mistreated his white traveling companion, Buffum, and found Douglass too “willing . . . to magnify the smallest causes of discomfort or wounded self esteem into . . . insurmountable hills of offense.” Webb accused Douglass of selfishness and “unreasonableness . . . when he thinks himself hurt.” Their relationship stumbled on with much private grumbling by both men. Webb was thirteen years older than the star orator, who was indeed insecure and hypersensitive in his first foreign sojourn; Douglass did not take well to constant mentorship and oversight. They did share, however, the publication of the Irish edition of the autobiography, although its author found it unsatisfying. By late September, Webb’s print shop on Great Brunswick Street had published the first Irish edition of Douglass’s Narrative with a print run of two thousand copies. Thus, the young American abolitionist could stay stocked for a while on what now became a busy speaking schedule around the Emerald Isle. Douglass received as many invitations to speak at temperance meetings as at (his preference) those about international abolitionism. Before he left Dublin, after seeing both its great halls as well as its desperate poverty, Douglass had the special experience of witnessing a speech by Daniel O’Connell and then meeting the “Great Liberator.”11

Legendary champion of all reforms, including the controversial repeal of the union of Ireland and England, O’Connell deeply moved Douglass, who was ever the student of oratory and still learning his craft. He had never heard a speech, Douglass wrote home, at which he “was more completely captivated.” The address was “skillfully delivered, powerful in its logic, majestic in its rhetoric, biting in its sarcasm, melting in its pathos, and burning in its rebukes”—all the same oratorical elements Douglass had tried to master. By early October, Douglass and Buffum were off to speaking engagements in Wexford and Waterford, then traveled the difficult roads by stagecoach down the east coast to Cork.12

In Cork, on the southern coast of Ireland, Douglass may have felt safer. Here for a month in the fall of 1845, Douglass experienced a kind of sanctuary, living with the Jennings family in their sprawling house on Brown Street, only steps down from Coal Quay on the River Lee. Thomas and Ann Jennings, with their eight curious and educated children, were religious dissenters in a city of Roman Catholics in a country ruled by the bishops of the Church of England. Jennings was a successful merchant who sold mineral oil, vinegar, and other farm goods from Cork’s ocean port. Full of quirks and fascinations for universal reforms, and lovers of music and literature, the Jennings family extended to Douglass a kind of humane racial equality he had never quite known. None of them sought to control Douglass in any way. He seemed to relish talking with the Jennings children, especially the young daughters, Isabel, Charlotte, Helen, and Jane, who were enthralled with their American guest. Her large family was not easily impressed, reported Jane Jennings, but no speaker had ever “excited such general interest as Frederick,” and he had “won the affection of everyone of us.”13

Isabel Jennings in particular, who was secretary of the Cork Ladies Anti-Slavery Society, and who worked assiduously to collect funds and material goods for antislavery fairs in America, became Douglass’s admirer and advocate. “He feels like a friend whom we had long known,” she wrote to Chapman in the fall of 1845, “and I think before he goes we will quite understand one another. He is so free in acknowledging when he has been too hasty in judging.” Isabel gushed over the stunning man making news in her town and her house. “There is an expression of great suffering at times on his countenance which only renders him more interesting.” Chapman might have been even further intrigued by Douglass’s impact on young Isabel when the Irish girl wrote, “There never was a person who made a greater sensation in Cork amongst all the religious bodies . . . in private he is greatly to be liked—he has gained friends everywhere he has been—he is indeed a wonderful man.”14

Such a private, welcoming kind of comfort nourished the weary traveler so far from home; and Douglass relished all the adoration from young women, a pattern he would repeat many times in his life, finding emotional support from women of all ages. But the orator-writer was on a public mission and very much on display. Douglass was now the perpetual guest of honor with bookings to speak nearly everywhere people might gather. In nearly every waking hour, if with people, he provided the object for their curiosity and gaze: he had to be the black man who was really a pleasing brown and partly white, the slave who was also so eloquent, the genius that bondage could not destroy, the embodiment of a story that kept on giving. A press report of his first speech in Cork, given at Lloyd’s Hotel, demonstrated the exoticized scrutiny Douglass faced with his Irish and British audiences. Enthralled with his mixed parentage, the reporter declared the orator’s “appearance . . . singularly pleasing and agreeable. The hue of his face and hands is rather yellow brown or bronze, while there is little, if anything, in his features of that peculiar prominence of lower face, thickness of lips, and flatness of nose, which peculiarly characterize the true Negro type. His voice is well toned and musical.” Exasperated by these racial characterizations, which he encountered almost everywhere, Douglass sometimes snapped back, declaring in a Cork newspaper that they “looked like a good advertisement from a slave trader.”15 Such racialized descriptions are hardly surprising in the middle of the nineteenth century; but such ideas and expectations were part of Douglass’s daily encounters, even among friends and admirers.

Douglass was not sui generis for the Irish of Cork or other provincial towns; Charles Lenox Remond had visited before him. But a black American former slave with such mastery of language and physical attractiveness had never landed in their midst before. Men listened to Douglass with intensity, as did women, some of whom swooned. In his numerous lectures in Cork, Douglass was an instant celebrity. The “ladies” especially turned out in droves to see and hear him, the Cork press observed. They did so as well in Belfast a couple of months later, where one Irishwoman abolitionist observed after seeing Douglass, “I am convinced that there is scarcely a lady in Belfast who would not be anxious to join in any means calculated to promote the enfranchisement of the deeply injured Africans.”16 But all this attention, getting his Narrative published, and his own deep personal sensitivities to racial slights, and to all those in the Garrisonian orbit who tried to control him, embroiled the star itinerant in turbulent personality conflicts.

First there was Buffum, the ever-present companion and watchdog. Eleven years older than Douglass, Buffum possessed superb radical credentials and was a devout Garrisonian. He had worked to desegregate New England railroads and served as an officer in both antislavery societies and in a Fourierist utopian organization. But he was the American Anti-Slavery Society’s (the “old organization’s”) appointed guardian of the volatile young Douglass. He reported directly to the power behind Garrison’s throne, Maria Weston Chapman, who managed the office of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society in Boston and especially the personal habits and ideological commitments of Garrisonian lecturers. At meetings Buffum would usually speak first and only briefly and anecdotally as a setup man for a Douglass performance. He played Sancho Panza to Douglass’s Don Quixote in some ways. Though certainly not of any peasant background or wisdom, Buffum did come across as the self-sacrificing Christian, necessarily a bit awestruck with his young charge, perhaps at times exhibiting racial paternalism. Booking agent, monitor of Douglass’s arguments and behavior, Buffum became the friend from whom the orator needed to escape. Not unlike the Hundred Conventions tour of two years earlier, these two abolitionists were constantly in each other’s company, and the nerves rubbed thin, especially as Douglass became aware of how much Chapman, and therefore Garrison, was trying to shape his image, his rhetoric, even his every movement. Douglass began to champ at the bit as his sponsors tried to rein him in.

This arrangement could only lead to conflict. The farther they traveled through Ireland and on to Scotland, Buffum repeatedly informed Chapman or one of her sisters about the “great applause” Douglass received at every event and the “great good” he did for the cause. But problems erupted in early 1846 when Douglass learned that Chapman had charged Buffum and Richard Webb with keeping their eyes on Frederick’s ambitions, his ideological straying, and especially his desire for money gained from sales of his book. In an understatement, Buffum warned Chapman that Douglass was “quite sensitive” about such accusations. Webb went even further, writing to Chapman about his personal disdain for Douglass. Douglass, said Webb, had engaged in “offensive and ungrateful behavior” toward Buffum. The Dubliner thought the former slave the “least loveable and least easy of all the abolitionists with whom” he had associated. Webb unloaded bile on the young American, considering him all but incapable of kindness, and “extremely jealous and suspicious.”17 A psychological dance between an ever-rising star and his rivals in Ireland—the one a smothering travelmate and the other the publisher who could not provide books to his writer fast enough—became open emotional warfare, with the prompter of the nastiness, Chapman, improbably sitting in a Boston office. Douglass did not hide his wounded soul, born of his slave past and stoked in his celebrity present.

During his more than four months in Ireland, Douglass tried to sustain a cordial correspondence with Webb. Douglass frequently made aggressive demands for more books. He also used his new patron as a sounding board for the frustrations of constant travel and the demands of the overly curious public. “Everyone . . . seems to think he has a special claim on my time to listen to his opinion of me,” Douglass complained to Webb, illustrating the self-importance that so annoyed the Irishman. Douglass detested the frontispiece image Webb used for the second Irish edition of the Narrative, which came out in early 1846, and told him so in no uncertain terms. To Webb, if we put it in modern terms, the young black man was uppity and never satisfied by his own recognition. Douglass also inveighed against expectations that he should speak on disunionism, nonresistance, or other Garrisonian doctrines, preferring to sustain his mission as “purely an Antislavery one.” Douglass wanted to prescribe his own agenda, and as Webb complained to Chapman behind Douglass’s back, he would not listen to his handlers.18

Douglass had, after all, escaped from slavery; he owed so much to his allies in the extended house of Garrison, including to Buffum, who had personally paid for the young man’s passage on the Cambria. Douglass’s wife and children were dependent on white abolitionists’ charity and goodwill. He was trapped in a deal that both offered him the world and stifled the kind of freedom he perhaps cherished most—the freedom of mind and of the words he would choose to express himself. Without doubt, Douglass was hypersensitive to personal slights, especially if he sensed they were racial, and he moved through the social and intellectual circles of his foreign admirers with a natural distrust that put the burden of social intercourse on others. During the previous frenetic four to five years when the antislavery orator was in constant motion, Douglass had tried to forge a new sense of self—as a public man of intellect, of courageous activism, and now as a writer. He was ferociously competitive; he desperately needed friends, but would forever find forging close bonds, especially with men, difficult. The young adult Douglass always knew—and constantly rehearsed in front of audiences—that he was still that fugitive slave from an Eastern Shore cornfield, the pain of his whippings festering in his memory. In a sense he was forever hurt, and he did not take well to new hurts, even if only perceived or imagined. From under those crisp white shirts worn under the frock coat, the hair on his head growing high and parted neatly, Frederick fashioned an elegance that usually kept his rage against slavery submerged in social settings. But it would burst out in his platform rhetoric, and sometimes privately at his closest companions.

When he stepped onto and off platforms before hundreds of auditors, then personally sold them copies of his book as he shook their hands, how could this twenty-eight-year-old phenomenon, who had discovered just how much power he wielded over his audiences with his story, not have a high estimation of himself? He desperately wanted Irish and British abolitionists to like him; but if the Webbs, Buffums, or Chapmans could not loosen their clutches and dissolve their own prejudices, then he could keep running from their shadows, and sometimes telling them just what he thought. Plenty of welcoming eyes and temporary friends were in the audience at the next speech.

In March 1846, in a letter labeled “private,” Douglass wrote to Chapman, openly challenging her efforts to manage him. He tried to remain respectful when he found out the extent of her efforts to stifle his liberties, but he could not stanch his anger. Webb had read portions of Chapman’s letter to him, especially the accusations that Douglass would seek to enrich himself and that he might defect to the anti-Garrisonian British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, known in shorthand as the London Committee. Douglass barely controlled his rage, informing Chapman that he had sailed to England with $350 earned from the first American sales of his book, and that he now sustained himself largely from sale of the Irish edition. Douglass felt bitterly betrayed by Chapman’s request to Webb to “watch over” him. No “love of money” nor “hate of poverty” could drive him from the “sacred cause,” he declared. He found the insinuations “embarrassing” and “disappointing.” He had resisted the Liberty Party in America, so “why should I not withstand the London Committee?”19

Then he became very personal. “If I am to be watched over for evel [sic] rather than for good, by my professed friends I can say with propriety save me from my friends and I will take care of my enemies!” He returned his own acid for Chapman’s whispered betrayals. “If you wish to drive me from the Antislavery Society, put me under overseer ship and the work is done. Set someone to watch over me—for evil and let them be so simple minded as to inform me of their office, and the last blow is struck.” Douglass kept declaring himself an old organizationist, but this exchange might be the beginning of the end of his ideological and personal loyalty to Garrisonianism. Perhaps the fugitive from the Eastern Shore cornfield could be “bought,” but never, he insisted, for the wrong reasons. He would continue to sell his book, and he made no apologies.20

The Irish tour surged on. After six major events in Cork, with bands playing as part of the show, Douglass and Buffum trekked by stagecoach and carriage over difficult roads due north to Limerick in November 1845. At Limerick, Douglass openly criticized a local actor who performed a Jim Crow character in a minstrel show. He delivered many versions of his “Slaveholder’s Sermon” as well as stories from the Narrative as he hawked copies at the end of each speech. Douglass also began to address openly political topics such as the annexation of Texas, and what he called “America’s bastard republicanism.” Then it was on to Belfast in the north, where Douglass spent more than a month at the Victoria Hotel, paid for by local abolitionists.21

In Belfast in late 1845 and early 1846, Douglass gave some extraordinary speeches, especially on the old theme of religious hypocrisy and the proslavery complicity of the churches. He also told riveting tales of his youth, of his brutal religion-professing masters, and of his struggle for literacy. He analyzed the nature of race and of proslavery claims of Negro inferiority. Moreover, the American orator aggressively thwarted claims for what might be called the Irish analogy—that the oppression and poverty of the Irish was equivalent to American slavery. Since beginning his tour he had felt “accosted,” Douglass claimed, with the idea that many of the Irish lived as “slaves.” He acknowledged the tyranny of British rule, but asked for careful distinctions about “what slavery really is.” Mincing no words, Douglass argued that “slavery was not what took away any one right or property in man: it took man himself,” and “from himself, dooms him a degraded thing, ranks him with the bridled horse and muzzled ox, makes him a chattel personal, a marketable commodity.” With some in the crowd shouting, “Hear, hear,” Douglass asked, “Had they anything like this in Ireland?” “Ah no!” he shouted, not waiting for his audience’s reply. With time Douglass became ever more aggressive in denouncing such an equivalence between conditions in Ireland and America. By 1850 back in the United States, he was quite direct: “There is no analogy between the two cases. The Irishman is poor, but he is not a slave. He may be in rags, but he is not a slave.”22 Not all Irishmen agreed with him.

Everywhere he went, Douglass knew he had to continue “working wonders” and serving, as one Irish observer put it, as the “living example of the capabilities of the slave.” But to the “whispers” that he was an “imposter,” which surfaced, Douglass said in Belfast, he responded with both anger and humor. Dubliners, he said, had not needed so much as “a letter of introduction,” nor had anyone else at his dozens of speeches around Ireland. But with biting sarcasm, he declared of his new hosts, “What sensible people you are in Belfast! How cautious lest they should make a mistake!”23

On December 23, 1845, Douglass delivered a bravura effort about slavery and religious corruption to a mixed Belfast audience of Catholics and Protestants. In an oration that included at least ten direct uses or paraphrases of scriptural passages and parables, Douglass turned Christian principles into weapons against proslavery religion—in his own country and in the British Isles. This forceful performance offended some of his auditors, while others all but fell over laughing and cheering. Caustic and sneering, Douglass demolished the very idea of a Christian slaveholder. They could “not serve God and Mammon,” and they blasphemed in claiming any “fellowship with the meek and lowly Jesus.” He lifted Matthew 23:15 to condemn Christian “man-stealers” and “cradle-plunderers” as “Christ denounced the Scribes and Pharisees, when he said that they would compass sea and land to make one proselyte, and after they had made him, he was ten times the Child of Hell.” And he challenged the antislavery consciences of his audience. Would they be the “priest” who would not even see the suffering man by the side of the road, the “Levite” who looked and felt sympathy but chose a “middle course” and moved on, or would they be the “Samaritan” of compassion who bound the wounds of the victim? Or would they make Daniel’s choice to break the law, never worship an earthly king’s false gods, and risk death in the lions’ den? With his memory still swirling with revenge against Thomas Auld, Douglass assured his well-churched Irish crowds that “a man becomes the more cruel the more the religious element is perverted in him. It was so with my master.”24 Douglass had learned to seamlessly weave biblical stories into his oratory with compelling effect.

• • •

During Douglass’s months in Ireland the potato crop began to fail, and the greatest catastrophe in Irish history took hold in the countryside. A new fungal disease was first detected in Dublin in late August 1845, just as Douglass arrived on Irish shores. Its worst effects did not set in until a second wave of the potato blight in 1846. Within the next four years approximately 1 million Irish would die, first of epidemic infections, then of horrible dietary-deficiency diseases, and finally of outright starvation. Another 2 million would emigrate to the United States and Canada over the ensuing decade. The social, demographic, and political legacies of the Great Irish Famine still reverberate to this day. In the 1840s, two-thirds of the Irish population of 8.2 million made its living from subsistence agriculture, and most of them were fully dependent on the nutritious potato. When the crop began to show the brown splotches, then putrefy on the ground, huge numbers of people had nowhere to turn; they were soon caught up in the strained political entanglements at the heart of Ireland’s links to Great Britain. As a leading historian of the Great Famine, Christine Kinealy, has said, with Ireland’s “quasi-colonial status” within the British empire, “the United Kingdom was far from united.”25 No legacy of the famine is more embittered than the role of British policies, and imperial attitudes toward the Irish people in their time of greatest travail.

Douglass observed the horrors of Irish poverty, as well as the beginnings of the famine, although he could not have fully comprehended its causes and consequences at the time. As he barnstormed through Ireland, lecturing his hosts to reject the analogy of Irish suffering with American slavery, and demanding they open their Christian hearts as they fought with their own racial hypocrisies, a vast tragedy of mass death from hunger had begun its sweep through the Irish peasantry. The modern Irish writer Colm Tóibín remarked that contemporary literate observers of the ravages of the famine tended to write with a “mixture of flat description” while “desperately trying to describe the indescribable.” He quotes one withering firsthand account from 1846 of the dead at an Irish hut: “Near the hole that serves as a doorway is the last resting place of two or three children; in fact, this hut is surrounded by a rampart of human bones, which have accumulated to such a height in the threshold . . . the ground is now two feet beneath it.” These people had not been shot in a civil war, but had simply dropped dead from starvation. “In this horrible den,” the account continues, “in the midst of a mass of human putrefaction, six individuals, males and females, laboring under most malignant fever, were huddled together, as closely as were the dead in the graves around.” Douglass did not see this kind of death scene. But he saw the “extreme poverty and wretchedness” of the Irish “huts.”26 He was awed by them, and his prose was both inspired and stymied by them.

In a public letter to Garrison in February 1846, after he had moved on to Scotland, Douglass took time to reflect on what he had seen of Ireland. As the American abroad, he felt compelled to expose “other evils” than slavery. “I am not only an American slave,” he wrote, “but a man, and as such, am bound to use my powers for the welfare of the whole human brotherhood. I am not going through this land with my eyes shut, ears stopped, or heart steeled.” For the moment he put aside his disdain for the analogy between Irish misery and American slavery. Too many self-styled “philanthropists,” maintained Douglass, “care no more about Irishmen . . . than they care about the whipped, gagged, and thumb-screwed slave. They would as willingly sell on the auction block an Irishman, if it were popular to do so, as an African.” Now it was he making the equivalences between two kinds of suffering and evil. Although Douglass only glimpsed the famine’s beginnings, he did seem to comprehend what Christine Kinealy observes: “One of the most lethal subsistence crises in modern history occurred within the jurisdiction of, and in close proximity to, the epicenter of what was the richest empire in the world.”27

In his six weeks of wandering around the Dublin region, Douglass witnessed so many “painful exhibitions of human misery” that the fugitive slave from the sandy soil of the Eastern Shore could only “blush.” The streets everywhere were “literally alive with beggars,” many only “stumps of men . . . without feet, without legs, without hands, without arms.” Douglass recounted being surrounded by “more than a dozen . . . at one time . . . all telling a tale of woe.” The “little children in the street at a late hour of night . . . leaning against brick walls, fast asleep,” parents nowhere to be seen, especially shocked him. He bothered with no abstractions nor made any distinctions here between the slave boy scrambling for food at a trough and the homeless, starving child of famine. Douglass viscerally understood abandonment from his own childhood. One can read such an impulse in his descriptions of the Irish children “with none to look upon them, none to care for them. If they have parents, they have become vicious, and have abandoned them. Poor creatures! They are left without help, to find their way through a frowning world.”28 The Fred Bailey who had waited at Miss Lucretia’s window for morsels of food as he sang for attention stood awestruck at the starving Irish.

Douglass saw many of the Irish peasant huts. “Of all places to witness human misery, ignorance, degradation, filth and wretchedness,” wrote Douglass, “an Irish hut is pre-eminent.” After a long description of their dark bleakness and suffocating space, he could not resist his Garrisonian abolitionist’s sense of irony at the presence of a “picture representing the crucifixion of Christ pasted on the most conspicuous place on the wall.” Demonstrating that he did not yet grasp the nature and scale of the famine as it unfolded, as yet unaware of the draconian “poor laws” that would evict huge numbers of Irish farmers from land and force them into workhouses, Douglass the reformer argued that the immediate cause of such widespread poverty in Ireland was intemperance. In the faces of the most wretched of all, he claimed he could see the evidence that “drunkenness was still rife in Ireland.” As Tóibín suggested about other writers contemporary with the famine, Douglass’s own prose may have suffered a flattening, his thinking itself may have fallen lame, in the face of the “indescribable.”29 A brilliantly descriptive piece of travel journalism about extreme human suffering stumbled in the end over what seemed an obligatory nod to temperance propaganda.

Douglass had been deeply affected, even changed, by Ireland and her people. He had learned from and fought ideological and personal battles with them. He had found yet a new range of his powerful voice, and he relished the new throngs of admirers. In Bondage and Freedom, written nine years after he left Belfast, while remembering nostalgically the “almost constant singing” among slaves in the South as they worked, the “deep melancholy” of the “wild notes,” his memory quickly leaped back to Ireland. “I have never heard any songs like those anywhere since I left slavery, except when in Ireland. There I heard the same wailing notes, and was much affected by them. It was during the famine of 1845–6.” It seemed that only Irish starvation allowed him, through memory, to share the agony of Anthony’s lash, Auld’s kitchen, the Easton jail, and Covey’s farmstead. Just which Irish songs he heard he does not tell us. But from his travels, like so many before and after him, Douglass brought away both a real and a mythic sense of the Irish people and their beautiful and terrible land. Maybe he even heard some versions of the longing and loss in “The Green Fields of Americay.”30

As he prepared to leave Ireland, Douglass crafted one of his public letters to Garrison on January 1, 1846. The letter exhibits homesickness on New Year’s Day, as he sat alone in a hotel in Belfast. But he also used his more than four months in Ireland as a springboard for one of the most embittered critiques he ever wrote about his own homeland. “I have spent some of the happiest moments of my life since landing in this country,” Douglass assured his readers. “I seem to have undergone a transformation. I live a new life.” He had been stunned by the lack of racial prejudice, the cordiality of his Irish friends. They had “flocked” to hear his words by the “thousands.” In literary terms he made the utmost of national contrasts: “Instead of the bright blue sky of America, I am covered with the soft grey fog of the Emerald Isle.” And yet, “I breathe, and lo! The chattel becomes a man.” Douglass drifted into a remarkable statement about patriotism full of pain and longing. Did any American exile in the long history of this story of the scorned expatriate ever express such feelings of a man without a country any better? “I have . . . no creed to uphold, no government to defend; and as a nation, I belong to none . . . The land of my birth welcomes me to her shores only as a slave.”31 It was as if the deep sadness of Irish songs had entered his bones.

Then Douglass turned, as he so often did in his writing, to metaphors of nature to find the beauty and the agony in his story. “In thinking of America, I sometimes find myself admiring her bright blue sky,” he rhapsodized, “her grand old woods—her fertile fields—her beautiful rivers . . . her star-crowned mountains.” We can read him anticipating Walt Whitman, Langston Hughes, or Woody Guthrie. “But my rapture is soon checked, my joy is soon turned to mourning. When I remember that all is cursed with the infernal spirit of slaveholding . . . when I remember that with the waters of her noblest rivers, the tears of my brethren are borne to the ocean . . . and that her most fertile fields drink daily of the warm blood of my outraged sisters, I am filled with unutterable loathing.” Douglass displays here what he would express repeatedly in his public life. He desperately wanted to belong in his own country, to make its stated creeds his own, but as he concluded, “America will not allow her children to love her.” Hatred and love of country, impossible condition mixed with plausible hope, brutally racist law met with resistance born of secular and religious faith—these were forever the literary and intellectual wellsprings of this great ironist’s work. He converted the remainder of his extraordinary last letter from Ireland into a litany of the ways he had faced Jim Crow’s ugliest rebukes back home, ending each of seven examples with the refrain, “We don’t allow n___ers in here!”32 He had not heard that Americanism in Ireland, and no mob had taken brickbats and clubs to drive him from a lectern.

Shortly after arriving in Scotland, Douglass wrote his preface for the second Irish edition of his Narrative, the one he would now hope to sell to finance his tour of Britain. He gave four reasons for his tour of the British Isles, all reasonable and revealing. First, he wanted to “be out of the way” as his full identity as a fugitive slave emerged more widely in the United States. Second, he sought a new “stock of information” and “opportunities for self-improvement” in the “land of my paternal ancestors,” a comment that kept many white Englishmen and Americans talking about his mixed blood for a long time. Third, he wished to spread the abolitionist crusade as far and wide as possible, to shame America before the wider world out of “her adhesion to a system so abhorrent to Christianity and to her republican institutions.” And fourth, he wanted auditors for his lectures and especially readers for his book. His campaign sought to prove that he was a writer in a land that honored and celebrated people of the word. In an appendix he chose to include several “critical notices” about the Narrative. Two of them came from Belfast ministers who raved about the book’s merits. Thomas Drew, a Church of Christ divine, wove Douglass’s achievement into praise of God, but not without admitting that when reading the Narrative “the details of the writer absorbs all attention,” and that the author was “a mind bursting all bounds.” Even more, the Presbyterian minister Isaac Nelson called Douglass a “literary wonder . . . such an intellectual phenomenon as only appears at times in the republic of letters.”33 Douglass had indeed accomplished that most wondrous of things for a slave: he had written a book the world would read!