“Balzac has secured the mythic constitution of the world through precise topographic contours. Paris is the breeding ground of his mythology—Paris with its two or three great bankers (Nucingen, du Tillet), Paris with its great physician Horace Bianchon, with its entrepreneur César Birotteau, with its four or five great cocottes, with its usurer Gobseck, with its sundry advocates and soldiers. But above all—and we see this again and again—it is from the same streets and corners, the same little rooms and recesses, that the figures of this world step into the light. What else can this mean but that topography is the ground plan of this mythic space of tradition, as it is of every such space and that it can become indeed its key.”

—WALTER BENJAMIN

Modern myths, Balzac observes in The Old Maid, are less well-understood but much more powerful than myths drawn from ancient times. Their power derives from the way they inhabit the imagination as indisputable and undiscussable realities drawn from daily experience rather than as wondrous tales of origins and legendary conflicts of human passions and desires. This idea, that modernity must necessarily create its own myths, was later taken up by Baudelaire in his critical essay “The Salon of 1846.” He there sought to identify the “new forms of passion” and the “specific kinds of beauty” constituted by the modern, and criticized the visual artists of the day for their failure “to open their eyes to see and know the heroism” around them. “The life of our city is rich in poetic and marvelous subjects. We are enveloped and steeped as though in an atmosphere of the marvelous; though we do not notice it.” Invoking a new element, “modern beauty,” Baudelaire concludes his essay thus: “The heroes of the Iliad are pygmies compared to you, Vautrin, Rastignac and Birotteau” (all characters out of Balzac’s novels) “and you, Honoré de Balzac, you the most heroic, the most extraordinary, the most romantic and the most poetic of all the characters you have produced from your womb.”1

Figure 13 Daumier’s view of the new Rue de Rivoli (1852) captures something of Balzac’s prescient descriptions of Paris, beset by “building manias” (witness the pickax being wielded in the background) and appearing as a “rushing stream,” as “a monstrous miracle, an astounding assemblage of movements, machines and ideas” in which “events and people tumble over each other” such that “even negotiating the street can be intimidating.”

Balzac painted in prose, but could hardly be accused of failing to see the richness and the poetry of daily life around him. “Could you really grudge,” he asks, “spending a few minutes watching the dramas, disasters, tableaux, picturesque incidents which arrest your attention in the heart of this restless queen of cities?” “Look around you” as you “make your way through that huge stucco cage, that human beehive with black runnels marking its sections, and follow the ramifications of the idea which moves, stirs and ferments inside it.”2 Before Baudelaire issued his manifesto for the visual arts (and a century before Benjamin attempted to unravel the myths of modernity in his unfinished Paris Arcades project), Balzac had already placed the myths of modernity under the microscope and used the figure of the flaneur to do it. And Paris—a capital city being shaped by bourgeois power into a city of capital—was at the center of his world.

The rapid and seemingly chaotic growth of Paris in the early nineteenth century rendered city life difficult to decipher, decode, and represent. Several of the novelists of the period struggled to come to terms with what the city was about. Exactly how they did so has been the subject of intensive scrutiny.3 They recorded much about their material world and the social processes that flowed around them. They explored different ways to represent that world and helped shape the popular imagination as to what the city was and might become. They considered alternatives and possibilities, sometimes didactically (as did Eugène Sue in his famous novel Les Mystères de Paris), but more often indirectly through their evocations of the play of human desires in relation to social forms, institutions, and conventions. They decoded the city and rendered it legible, thereby providing ways to grasp, represent, and shape seemingly inchoate and often disruptive processes of urban change.

How Balzac did this is of great interest because he made Paris central—one might almost say the central character—in much of his writing. But “The Human Comedy” is a vast, sprawling, incomplete and seemingly disparate set of works, made up of some ninety novels and novellas written in just over twenty years between 1828 and his death (attributed to drinking too much coffee) in 1850, at the age of fifty-one. Exhuming the myths of modernity and of the city from out of this incredibly rich and often confusing oeuvre is no easy task. Balzac had the idea of putting his various novels together as “The Human Comedy” in 1833, and by 1842 settled on a plan that divided the works into scenes of private, provincial, Parisian, political, military, and rural life, supplemented by a series of philosophical and analytical studies.4 But Paris figures almost everywhere (sometimes only as a shadow cast upon the rural landscape). So there is no option except to track the city down wherever it is to be found.

Reading through much of “The Human Comedy” as an urbanist (rather than as a literary critic) is a quite extraordinary experience. It reveals all manner of things about a city and its historical geography that might otherwise remain hidden. Balzac’s prescient insights and representations must surely have left a deep imprint upon the sensibility of his readers, far beyond the literati of the time. He almost certainly helped create a climate of public opinion that could better understand (and even accept, though unwittingly or regretfully so) the political economy that underlays modern urban life, thus shaping the imaginative preconditions for the systematic transformations of Paris that occurred during the Second Empire. Balzac’s supreme achievement, I shall argue, was to dissect and represent the social forces omnipresent within the womb of bourgeois society. By demystifying the city and the myths of modernity with which it was suffused, he opened up new perspectives, not only on what the city was, but also on what it could become. Just as crucially, he reveals much about the psychological underpinnings of his own representations and furnishes insights into the murkier plays of desire (particularly within the bourgeoisie) that get lost in the lifeless documentations in the city’s archives. The dialectic of the city and how the modern self might be constituted is thereby laid bare.

The “only solid foundation for a well-regulated society,” Balzac wrote, depended upon the proper exercise of power by an aristocracy secured by private property, “whether it be real estate or capital”5 The distinction between real estate and capital is important. It signals the existence of a sometimes fatal conflict between landed wealth and money power. Balzac’s utopianism most typically appeals to the former. What the literary theorist Fredric Jameson calls “the still point” of Balzac’s churning world focuses on “the mild and warming fantasy of landed property as the tangible figure of a Utopian wish fulfillment.” Here resides “a peace released from the competitive dynamism of Paris and of metropolitan business struggles, yet still imaginable in some existent backwater of concrete social history.”6

Balzac often invokes idyllic pastoral scenes from the earliest novels (such as The Chouans) onwards. The Peasantry, one of his last novels, opens with a long letter composed by a Parisian royalist journalist describing an idyllic “arcadian” scene of a country estate and its surroundings, contrasted with “the ceaseless and thrilling dramatic spectacle of Paris, and its harrowing struggles for existence.” This idealization then frames the action in the novel and provides a distinctive perspective from which social structures can be observed and interpreted. In The Wild Ass’s Skin, the utopian motif moves center stage. Raphael de Valentin, seeking the repose that will prolong his threatened life, “felt an instinctive need to draw close to nature, to simplicity of dwelling and the vegetative life to which we so readily surrender in the country.” He needs the restorative and rejuvenating powers that only proximity to nature can bring. He finds “a spot where nature, as light-hearted as a child at play, seemed to have taken delight in hiding treasure,” and close by came upon:

a modest dwelling-house of granite faced with wood. The thatched roof of this cottage, in harmony with the site, was gay with mosses and flowering ivy which betrayed its great antiquity. A wisp of smoke, too thin to disturb the birds, wound up from the crumbling chimney. In front of the door was a large bench placed between two enormous bushes of honeysuckle covered with red, sweet-scented blossoms. The walls of the cottage were scarcely visible under the branches of vine and the garlands of roses and jasmine which rambled around at their own sweet will. Unconcerned with this rustic beauty, the cottagers did nothing to cultivate it and left nature to its elvish and virginal grace.

The inhabitants are no less bucolic:

The yelping of the dogs brought out a sturdy child who stood there gaping; then there came a white-haired old man of medium height. These two matched their surroundings, the atmosphere, the flowers and the cottage. Good health brimmed over in the luxuriance of nature, giving childhood and age their own brands of beauty. In fact, in every form of life there was that carefree habit of contentment that reigned in earlier ages; mocking the didactic discourse of modern philosophy, it also served to cure the heart of its turgid passions.7

Figure 14 Daumier often made fun of the pastoral utopianism of the bourgeoisie. Here the man proudly points out how pretty his country house looks from here, adding that next year, he plans to have it painted apple green.

Utopian visions of this sort operate as a template against which everything else is judged. In the closing phases of the orgy scene in The Wild Ass’s Skin, for example, Balzac comments how the girls present, hardened to vice, nevertheless recalled, as they awoke, days gone by of purity and innocence spent happily with family in a bucolic rustic setting. This pastoral utopianism even has an urban counterpart. Living penniless in Paris, Raphael had earlier witnessed the impoverished but noble life of a mother and daughter whose “constant labor, cheerfully endured, bore witness to a pious resignation inspired by lofty sentiments. There existed an indefinable harmony between the two women and the objects around them.”8 Only in The Country Doctor, however, does Balzac contemplate the active construction of such a utopian alternative. It takes a supreme act of personal renunciation on the part of the doctor—a dedicated, compassionate, and reform-minded bourgeois—to bring about the necessary changes in a rural area of chronic ignorance and impoverishment. The aim is to organize harmonious capitalist production on the land by way of a collaborative communitarian effort that nevertheless emphasizes the joys of private property. Balzac hints darkly, however, at the fragility of such a project in the face of peasant venality and individualism. But again and again throughout “The Human Comedy” we find echoes of this utopian motif as a standpoint from which social relations can be understood.

Balzac looked for the most part to the aristocracy to provide leadership. Their duties and obligations were clear: “Those who wish to remain at the head of a country must always be worthy of leading it; they must constitute its mind and soul in order to control the activity of its hands.” But it is a “modern aristocracy” that must now emerge, and it must understand that “art, science and wealth form the social triangle within which is inscribed the shield of power.” Rulers must “have sufficient knowledge to judge wisely and must know the needs of the subjects and the state of the nation, its markets and trade, its territory and property.” Subjects must be “educated, obedient,” and “act responsibly” to partake “of the art of governance.” “Means of action,” he writes, “lie in positive strength and not in historic memories.” He admires the English aristocracy (as did Saint-Simon, as we shall see) because it recognized the need for change. Rulers have to understand that “institutions have their climacteric years when terms change their meaning, when ideas put on a new garb and the conditions of political life assume a totally new form without the basic substance being affected.”9 This last phrase, “without the basic substance being affected,” takes us back, however, to the still point of Balzac’s pastoral utopianism.

A modern aristocracy needs money power to rule. If so, can it be anything other than capitalist (albeit of the landed sort)? What class configuration can support this utopian vision? Balzac clearly recognizes that class distinctions and class conflict cannot be abolished: “An aristocracy in some sense represents the thought of a society, just as the middle and working classes are the organic and active side of it.” Harmony must be constructed out of “the apparent antagonism” between these class forces such that “a seeming antipathy produced by a diversity of movement.… nevertheless works for a common aim.” Again, there is more than a hint of Saint-Simonian utopian doctrine in all of this (though Saint-Simon looked to the industrialists rather than to the aristocracy for leadership). The problem is not, then, the existence of social differences and class distinctions. It is entirely possible for “the different types contributing to the physiognomy” of the city to “harmonize admirably with the character of the ensemble.” For “harmony is the poetry of order and all peoples feel an imperious need for order. Now is not the cooperation of all things with one another, unity in a word, the simplest expression of order?” Even the working classes, he holds, are “drawn towards an orderly and industrious way of life.”10

This ideal of class harmony fashioned out of difference is, sadly, disrupted by multiple processes working against it. Workers are “thrust back into the mire by society.” Parisians have fallen victim to the false illusions of the epoch, most notably that of equality. Rich people have become “more exclusive in their tastes and their attachment to their personal belongings than they were thirty years ago.” The aristocrats need money to survive and to assure the new social order; but the pursuit of that money power corrupts their potentialities. The rich consequently succumb to “a fanatical craving for self-expression.”11 The pursuit of money, sex, and power becomes an elaborate, farcical, and destructive game. Speculation and the senseless pursuit of money and pleasure wreak havoc on the social order. A corrupt aristocracy fails in its historic mission, while the bourgeoisie, the central focus of Balzac’s contempt, has no civilized alternative to offer.

These failures are all judged, however, in relation to Balzac’s utopian alternative. The pastoralism provides the emotive content and a progressive aristocracy secures its class basis. While the class perspective is quite different, Marx could nevertheless profess an intense admiration for the prescient, incisive, and clairvoyant qualities of Balzac’s analysis of bourgeois society in “The Human Comedy” and drew much inspiration from the study of it.12 We also admire it too because of the clarity it offers in demystifying not only the myths of modernity and of the city but also its radical exposure of the fetish qualities of bourgeois self-understandings.

While Balzac’s utopianism has a distinctively landed, provincial, and even rustic flavor, the contrast with actual social relations on the land and in the provinces could not be more dramatic. Innumerable characters in Balzac’s works undertake (as did Balzac himself) the difficult transition from provincial to metropolitan ways of life. Some, like Rastignac in Old Goriot, negotiate the transition successfully, while a priest in César Birotteau is so horrified by the bustle of the city that he stays locked in his room until he can return to Tours, vowing never to set foot in the city again. Lucien, in Lost Illusions and The Harlot High and Low, never quite makes the grade and ends up committing suicide. Still others, like Cousin Bette, bring their peasant wiles with them and use them to destroy the segment of metropolitan society to which they have intimate access. While the boundary is porous, there is a deep antagonism between provincial ways and those of the metropolis. Paris casts its shadow across the land, but with diminishing intensity the further away one moves. Brittany as depicted in The Chouans is like a far-off colonial outpost, and Burgundy and Angoulême are far enough away to evolve autonomous ways of life. Here the law is locally understood and locally administered, and everything depends on local rather than national power relations.

The distinctive pattern of class relations in the provinces is brilliantly laid out in The Peasantry. Balzac here sets “in relief the principal types of a class neglected by a throng of writers” and addresses the “phenomena of a permanent conspiracy of those whom we call ‘the weak’ against those who imagine themselves to be ‘the strong’—of the Peasantry against the rich.” That the weak have many weapons (as James Scott in more recent times has argued) is clearly revealed. Balzac portrays “this indefatigable sapper at his work, nibbling and gnawing the land into little bits, carving an acre into a hundred scraps, to be in turn divided, summoned to the banquet by the bourgeois, who finds in him a victim and an ally.” Beneath the “idyllic rusticity” there lies “an ugly significance.” The peasant’s code is not the bourgeois code, writes Balzac: “the savage” (and there is more than one comparison to James Fenimore Cooper’s portrayal of the North American Indian) “and his near relation, the peasant, never make use of articulate speech, except to lay traps for their enemies.”13

The struggle between the peasants and the aristocracy is fiercely joined, but the real protagonists in the action are a motley crew of local lawyers, merchants, doctors, and others hell-bent on accumulating capital by usurious practices, monopoly controls, legal chicanery, and the weaving of an intricate web of interdependencies and strategic alliances (cemented by opportunistic marriages). This group is locally powerful enough to defy or subvert the central authorities in Paris, to hem in aristocratic power, and to orchestrate events for their own benefit. The peasants are inevitably drawn into an alliance with local bourgeois interests against the aristocracy, even though they stand not to benefit from the outcome. The bourgeois lawyer Rigou, variously described as “the vampire of the valley” and “a Master of Avarice,” holds oppressive mortgages and uses them to extract forced labor from a peasantry he controls with “secret wires.” Cortecuisse, a peasant, borrowed money from Rigou to purchase a small estate, but never manages to pay more than the interest on the loan, no matter how hard he and his wife work. Constantly threatened with foreclosure, Cortecuisse can never go against Rigou’s will. And Rigou’s will is to use the power of the peasantry—in particular their chronic and ghastly impoverishment, their resentments, and their traditional rights to gleaning and to the extraction of wood—as a means to undermine the commercial viability of the aristocratic estate. Says one perceptive peasant:

Frighten the gentry at the Aigues so as to maintain your rights, well and good; but as for driving them out of the place and having the Aigues put up for auction, that is what the bourgeois want in the valley, but it is not in our interest to do it. If you help divide up the big estates, where are all the National lands to come from in the revolution that is coming? You will get the land for nothing then, just as old Rigou did; but once let the bourgeois chew up the land, they will spit it out in much smaller and dearer bits. You will work for them, like all the others working for Rigou. Look at Courtecuisse!14

While it was easier for the peasantry to go against the aristocracy and blame them for their degraded condition than to resist the local bourgeois upon whom they depended, the resentment of local bourgeois power was never far from the surface. For how long, then, could it be controlled, and did not the bourgeoisie in both Paris and the countryside have reason to fear it? Insofar as the countryside is a site of instability and class war, its threat to the Parisian world becomes all too apparent. While Paris may reign, it is the countryside that governs.15

Parisians of all classes lived in a state of denial and distrust of their rural origins. The complex rituals of integration of provincial migrants into the city can be explained only in such terms. Having viciously picked apart the small-town provincialisms of Angoulême in the opening part of Lost Illusions, Balzac describes excruciating scenes as Lucien and Madame de Bargeton move to Paris to consummate their passion. Taken to the opera by the well-connected Madame d’Espard, Lucien, who has already spent much of the little money he has on clothes, is scrutinized variously as “a tailor’s dummy” or as a “shopkeeper in his Sunday best.” When it transpires that he is actually the son of an apothecary and really has no claim to his mother’s aristocratic lineage, he is shunned altogether, including by Madame de Bargeton. The latter fares little better at first. In Paris she appears to Lucien as “a tall, desiccated woman with freckled skin, faded complexion and strikingly red hair; angular, affected, pretentious, provincial of speech and above all badly dressed.” The butt of barbed comments from many at the opera, she is saved because everyone could see in Madame d’Espard’s companion “a poor relation from the provinces, and any Parisian family can be similarly afflicted.”16 Under Madame d’Espard’s tutelage, Madame de Bargeton is quickly initiated into Parisian mores, though now as Lucien’s enemy rather than his lover.

Figure 15 In Daumier’s view, the realities of rural life were far from idyllic. The bourgeoisie either encountered horrible accidents (usually provoked by untoward encounters with rural life) or else suffered from boredom.

Balzac frequently recounts scenes of ritual incorporation into Parisian life out of provincial origins, no matter whether it be of a merchant (like César Birotteau), an ambitious young aristocrat (like Rastignac), or a well-connected woman (like Madame de Bargeton). Once incorporated, they never look back, even if they are ultimately destroyed (like Birroteau and Lucien) by their Parisian failures. The avid denial of provincial origins and of provincial powers thereby evolves into one of the founding myths of Parisian life: that Paris is an entity unto itself and that it does not rely in any way upon the provincial world it so despises. It is in Cousin Bette that we see how costly such a denial can be: a woman of peasant origins uses her wiles to destroy the aristocratic family whose status she so envies. Paris depended crucially upon its provinces but avidly sought to deny that fact.

The contrast between the leisurely pace of provincial and rural life and the daily rush in Paris is startling. Consider the wide range of metaphors that Balzac deploys to convey this sense of what Paris is about. The city, he writes, “is endlessly on the march and never taking rest,” it is “a monstrous miracle, an astounding assemblage of movements, machines and ideas, the city of a thousand different romances … a restless queen of cities.” In “the rushing stream of Paris,” events and people tumble pell-mell over each other. Even negotiating the street can be intimidating. Everyone, “conforming to his own particular bent, scans the heavens, hops this way and that, either in order to avoid the mud, or because he is in a hurry, or because he sees other citizens rushing along helter-skelter.” This frenetic pace, with its compressions of both time and space, in part derives from the way Paris has become a “vast metropolitan workshop for the manufacture of enjoyment.” It is a city “devoid of morals, principles and genuine feeling,” but one within which all feelings, principles, and morals have their beginning and their end. What Simmel later came to define as the “blasé attitude” so characteristic of the city of modernity is spectacularly evoked:

No sentiment can stand against the swirling torrent to events; their onrush and the effort to swim against the current lessens the intensity of passion. Love is reduced to desire, hate to whimsy … in the salon as in the street no one is de trop, no one is absolutely indispensable or absolutely noxious.… In Paris there is toleration for everything: the government, the guillotine, the Church, cholera. You will always be welcome in Parisian society, but if you are not there no one will miss you.17

The chaos of commodity markets compounds the confusions:

The rue Perrin-Gasselin is one byway in the labyrinth … forming, as it were, the entrails of the town. It swarms with an infinite variety of commodities—various and mixed, stinking and stylish, herrings and muslin, silks and honey, butter and tulles—and above all a host of little shops, of which Paris no more suspects the existence than most men suspect what is going on in their pancreas.18

To find out how this Paris works, to get beneath the surface appearance, the mad jumble, and the kaleidoscopic shifts, to penetrate the labyrinth, you have “to break open the body to find therein the soul.” But it is there, at the core, that the emptiness of bourgeois life becomes all too evident. While the dominant forces at work are interpreted in various ways, behind them loom figures like Giggonet the discounter, Gobseck the banker, and Rigou the moneylender. Gold and pleasure lie at the heart of it all. “Take these two words as a guiding light,” and all will be revealed because, we are told, “not a cog fails to fit into its groove and everything stimulates the upward march of money.” In Paris “people of all social statures, small, medium and great, run and leap and caper under the whip of a pitiless goddess, Necessity: the necessity for money, glory or amusement.”19 The circulation of capital is in charge.

In particular, “the monster we call Speculation” takes over. Eugénie Grandet records a key historical moment of conversion: the miser who hoards gold becomes the rentier who speculates in interest-bearing notes, thereby equating self-interest with monetary interest. Marx may have had Grandet in mind when he wrote: “The boundless greed after riches, this passionate chase after exchange value, is common to the capitalist and the miser; but while the miser is merely a capitalist gone mad, the capitalist is a rational miser.”20 So it is with Grandet. But it is speculation of all sorts that rules. The working classes speculate as “they wear themselves out to win the gold which keeps them spellbound, “ and will even take to revolution, “which it always interprets as a promise of gold and pleasure!” The “bustling, scheming, speculating” members of the lower middle classes assess demand in Paris and reckon to cater for it.” They forage the world for commodities, “discount bills of exchange, circulate and cash all sorts of securities” while making “provision for the fantasies of children,” spying out “the whims and vices of grown-ups.” They even squeeze out “dividends from diseases” as they offer spurious remedies for real and imagined ills.21 César Birotteau, a perfumer, pioneers the use of advertising to persuade everyone of the superiority of his product, thus driving out all rivals. At an even grander level, speculation in house property and land rents reshapes the city:

Paris may be a monster, but it is the most monomaniacal of monsters. It falls for a thousand fantasies. At one moment it takes to brick-laying like a lord enamoured of the trowel.… Then it falls into the slough of despond, goes bankrupt, sells up and files its petition. But a few days later, it puts its affairs in order, sallies forth in holiday and dancing mood.… It has its day to day manias, but also its manias for the month, the season, the year. Accordingly, at that moment, the whole population was demolishing or rebuilding something or other, somehow or other.22

Returns from real estate speculation may, however, be slow and erratic (it took eight years for the crafty bourgeois Crevel in Cousin Bette to realize the benefits of rising rents from neighborhood improvements, and those, like César Birotteau, who have not enough credit to wait, can lose all to unscrupulous financiers). We even witness something we now call “gentrification”: “In building fine and elegant houses with a porter’s lodge, laying footpaths and putting in shops, speculative builders, by the high rents that they charge, tend to drive away undesirable characters, families without possessions, and every kind of bad tenant. And it is in this way that districts rid themselves of their disreputable population.”23 Grand financiers stand ready not only to ruin honest bourgeois investors like Birotteau but also, as with Baron Nucingen, to swindle poor people out of their money. “Do you know what he calls doing a good stroke of business?” asks Madame Nucingen of a shocked Goriot:

He buys undeveloped land in his own name then has houses built on it acting through men of straw. These men draw up the contracts for the buildings with all the contractors and pay them with long-dated bills. They hand over possession of the houses to my husband for a small sum, and slide out of their debt to the duped contractors by going bankrupt.24

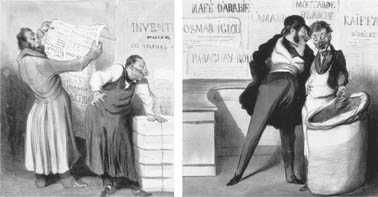

Figure 16 Daumier represented Balzac’s figure of the “bustling, scheming, speculating” members of the lower classes in an extensive series depicting Robert Macaire, a charlatan, opportunist, and braggart always out for quick success. He here offers to sell shares “to those prepared to lose money” and advises a salesman that he will realize a lot more profit if he grinds up his product into powder, or turns it into a lotion and sells it as a remedy for some ailment. When told the sack contains corn, he merely replies, “So much the better!”

The guiding strings of power in this new society lie within the credit system. A few clever financiers (Nucingen and Gobseck in Paris, Rigou in Bourgogne) occupy nodal points in networks of power that dominate everything else. Balzac exposes the fictions of bourgeois power and values. This is a world where fictitious capital—dominated by bits of paper credit augmented by creative accounting—holds sway, where everything (as Keynes much later was to argue in his General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, and as our own recent spate of financial scandals illustrates) dances to the tune of expectations and anticipations with only accidental relationship to honest toil. This fictive world carries over into personal behaviors; to adopt all the trappings of wealth, particularly to assume the clothing of its outward signs (dress, carriage, servants, well-furnished apartments), and to go into debt to do it, is a necessary prelude to achievement of wealth. Fiction and fantasy, particularly the fictions of credit and interest, become reality. This is one of the key founding myths of modernity. And this is what all the sophisticated social facades and all the chaotic turbulence of “the rushing stream” conceal. Balzac peels away the fetishism (the idea that financial chicanery is accidental rather than structural) and exposes the fictions to reveal the utter emptiness of bourgeois values within. Dancing in this way to the tune of “her highness political economy” may even have revolutionary implications:

The needs of all classes, consumed by vanity, are overexcited. Politics no less fearfully than morality must ask itself where the income is to come from to meet these needs. When one sees the floating debt of the Treasury and when one becomes acquainted with the floating debt of each household which models itself on the state, one is shocked to see that a half of France is in hock to the other half. When accounts are settled, the debtors will be far ahead of the creditors.… This will probably signal the end of the so-called era of industry.… The rich bourgeoisie has many more heads to cut off than the nobility; and even if they have the guns they will find their adversaries among those that make them.25

In 1848 the truth of this became all too evident.

Though the surface appearance is of atomistic and chaotic competition between individuals in a relentless struggle for gold, power, and pleasure, Balzac penetrates behind this chaotic world of appearance to construct an understanding of Paris as a product of constellations and clashes of class forces. In The Girl with the Golden Eyes he deploys an amazing mixture of metaphors to describe this class structure. Dante’s vision (which seems to have inspired Balzac’s overall choice of title, “The Human Comedy”) of spheres in the descent into hell is first invoked: “For it is not only in jest that Paris has been called an inferno. The epithet is well deserved. There all is smoke, fire, glare, ebullience; everything flares up, falters, dies down, burns up again, sparkles, crackles and is consumed.… It is for ever vomiting fire and flame from its unquenchable crater.”26 Balzac rapidly shifts metaphors, and we find ourselves first ascending through the floors of a typical Parisian apartment building, noting the class stratification as we go up, then viewing Paris as a ship of state manned by a motley crew, and then, finally, probing into the lobes and tissues of the body of Paris considered as either a harlot or a queen.

But the class structure throughout is clear. At the bottom of the pile is the proletariat, “the class which has no possessions.” The worker is the man who “overtaxes his strength, harnesses his wife to some machine or other, and exploits his child by gearing him to a cog wheel.” The manufacturer is the intermediary who pulls on guiding strings (a language that Marx echoes when he comments on the invisible threads through which capital commands domestic industries in a unified system of production) to put “these puppets” in motion in return for promising this “sweating, willing, patient, industrious populace” a lavish enough wage “to cater to a city’s whims on behalf of that monster we call Speculation.” Thereupon the workers “set themselves to working through the night watches, suffering, toiling, cursing, fasting and forging along: all of them wearing themselves out in order to win the gold which keeps them spellbound.” This proletariat, amounting to three hundred thousand people by Balzac’s estimate, typically flings away its hard-earned wealth in the taverns that surround the city, exhausts itself with debauchery, explodes occasionally into revolutionary fervor, and then falls back into sweated labor. Pinned like Vulcan to the wheel (an image that Marx also invokes in Capital) there are nevertheless some workers of exemplary virtue who typify “its capacities raised to their highest expression and sum up its social potentialities in a kind of life in which mental and bodily activity are combined.” Still others carefully harbor their incomes to set up as small retailers—encapsulated in Balzac’s figure of “the haberdasher” who achieves a rather different lifestyle of respectable family life, sessions reading the newspaper, visits to the Opera and to the new dry goods stores (where flirtatious shop attendants await him). He is typically ambitious for his family and values education as a means to upward mobility.27

The second sphere is constituted by “wholesale merchants and their staffs, government employees, small bankers of great integrity, swindlers and cats paws, head clerks and junior clerks, bailiffs’, solicitors’ and notaries’ clerks, in short the bustling, scheming, speculating members of that lower middle class that assesses demand in Paris and reckon to cater to it.” Burned up with desire for gold and pleasure, and driven by the flail of self-interest, they, too, “let their frantic pace of life ruin their health.” Thus they end their days dragging themselves dazedly along the boulevard with “worn, dull and withered” faces, “dim eyes and tottering legs.”

The third circle is “as it were, the stomach of Paris in which the interests of the city are digested and compressed into a form which goes by the name of affaires.” Here, “by some acrid and rancorous intestinal process” we find an upper middle class of “lawyers, doctors, barristers, business men, bankers, traders on the grand scale.” Desperate to attract and accumulate money, those who have hearts leave them behind as they descend the stair in early morning, “into the abyss of sorrows that put families to the torture.” Within this sphere we find the cast of characters (immortalized in Daumier’s satirical series on Robert Macaire) who dominate within the whole corpus of Balzac’s work and about whom he has so much critical to say. This is the class that now dominates even though it does so in self-destructive ways that encompass its own ruinous practices, activities, and attitudes.28

Above this lives the artist world, struggling (like Balzac himself) to achieve originality but “ravaged, not ignobly, but ravaged, fatigued, tortured” and (again like Balzac himself) “incessantly harassed by creditors,” so that they succumb to both vice and pleasure as compensation for their long nights of overwork as they “seek in vain to conciliate mundane dalliance with the conquest of glory and money with art.” “Competition, rivalry and calumny are deadly enemies to talent,” Balzac observes (and we have to look no further than the corruption of journalistic talent as depicted in Lost Illusions for examples of what this might mean).29 This now hegemonic middle class lives and works under the most appalling conditions, however:

Before we leave the four social tiers on which patrician wealth in Paris is built, should we not, having dealt with moral causes, make also some sounding about physical causes? … Should we not point out a deleterious influence whose corruptive action is equal only to that exerted by the municipal authorities who so complacently allow it to subsist? If the air of the houses in which the majority of the middle-class citizens live is foul, if the atmosphere of the street spews out noxious vapors into practically airless back premises, realize that, apart from this pestilence, the forty thousand houses of this great city have their foundations plunged in filth.… Half of Paris sleeps nightly in the putrid exhalations from streets, back-yards and privies.30

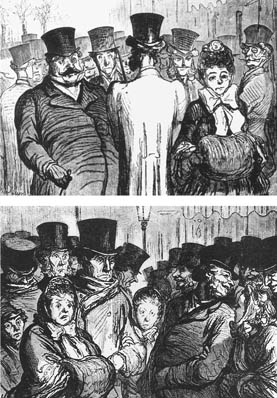

Figure 17 Daumier captures Balzac’s distinctive physiognomies of the different classes in this depiction of the affluent classes on the Boulevard des Italiens (top) and the “anxious” middle classes on the Boulevard du Temple (bottom).

These were the living conditions that Haussmann was summoned to address more than twenty years later. But the working conditions of the middle-class were no better (as the depictions of the squalid offices of the publishers around the Palais Royale in Lost Illusions graphically illustrate). They “live in insalubrious offices, pestilential courtrooms, small chambers with barred windows, spend their day weighed down by the weight of their affairs.”

All of this makes for a tremendous contrast with “the great, airy, gilded salons, the mansions enclosed in gardens, the world of the rich, leisured, happy, moneyed people” (typified by the exclusionary society centered on the Faubourg St. Germain). Yet, in Balzac’s dyspeptic account, the residents of this upper sphere are anything but happy. Corrupted by their search for pleasure (reduced to opium and fornication), bored, warped, withered and consumed by a veritable “bonfire of the vanities” (as Tom Wolfe later dubbed it when writing of New York), curiously preyed upon by the lower classes who “study their tastes in order to convert them into vices as a source of profit,” they live “a hollow existence” in anticipation of a “pleasure that never comes.” This was the class in whom Balzac invested all his utopian hopes, but perhaps exactly for that reason it assumes the ugliest of actual personas: “pasteboard faces, those premature wrinkles, that rich man’s physiognomy on which impotence has set its grimace, in which only gold is mirrored and from which intelligence has fled.”31

Balzac summarizes thus: “Hence it is that the phenomenal activity of the proletariat, the deterioration resulting from the multiple interests that bring down the two middle classes described above, the spiritual torments to which the class of artists is subjected and the surfeit of pleasure usually sought by the grandees, explain the normal ugliness of the Paris population.”32 Thus are the “kaleidoscopic” experience and “cadaverous physiognomy” of the city understood.

The seeming rigidity of these class distinctions (as well as crucial distinctions of provincial origin and social history) is offset by the rapid shifts that occur as individuals participate in the high-stakes pursuit of money, sex, and power. Lucien, for example, returns to his provincial origins penniless, powerless, and disgraced at the end of Lost Illusions, only to reappear in Paris reempowered by his association with the archcriminal Vautrin, who orchestrates his liaison with the wealthy mistress of Nucingen, the banker, in A Harlot High and Low. Rastignac lives among the impoverished but genteel boarders and students in Old Goriot but circulates among the nobility (borrowing from his family to get the costume to do it). “Each social sphere projects its spawn into the sphere immediately above it,” so that “the rich grocer’s son becomes a notary, the timber merchant’s son becomes a magistrate.”33 And, as we have seen, by adopting all the trappings of outward appearances of wealth, it is sometimes possible to actually realize that wealth through speculative action and the fraudulent management of social relations. Yet there are innumerable traps and limits to this process, as identifications and identities become glued together in the complex spaces of the Parisian social order.

In every zone of Paris “there is a mode of being which reveals what you are, what you do, where you come from, and what you are after.” The physical distances that separate classes are understood as “a material consecration of the moral distance which ought to separate them.” The separation of social classes exists as both spatial ecologies and vertical segregations. Paris has “its head in the garrets, inhabited by men of science and genius; the first floors house the well-filled stomachs; on the ground floor are the shops, the legs and feet, since the busy trot of trade goes in and out of them.” Balzac toys with our curiosity about the hidden spaces in the city, turns them into mysteries that pique our interest. “One is loath to tell a story to a public for whom local colour is a closed book,” he coyly states.34 But he immediately opens the book to reveal a whole world of spatiality and its representations. The spatial pattern anchors a moral order.

The sociologist Robert Park once wrote a suggestive essay on the city as a spatial pattern and a moral order; social relations were inscribed in the spaces of the city in such a way as to make the spatial pattern both a reflection of and an active moment in the reproduction of the moral order. This idea plays directly throughout Balzac’s fiction: “In every phase of history the Paris of the upper classes and the nobility has its own center, just as the plebeian Paris will always have its own special quarter.”35 Fine-grained variations are built into the sociospatial form of the city:

In Paris the different types contributing to the physiognomy of any portion of that monstrous city harmonize admirably with the character of the ensemble. Thus the concierge, door-keeper or hall porter, whatever the name given to this essential nerve system within the Parisian monster, always conforms to the quarter in which he functions, and often sums it up. The concierge of the Faubourg St. Germain, wearing braid on every seam, a man of leisure, speculates in government stocks; the porter of the Chaussée d’Antin enjoys his creature comforts; he of the Stock Exchange quarter reads his newspapers; porters in the Faubourg Montmartre work at a trade; in the quarter given over to prostitution the portress herself is a retired prostitute; in the Marais quarter she is respectable, cross-grained, and crotchety.36

This spatial pattern enforces a moral order (even beyond that ensured by the concierges and porters). In “Ferragus,” the first of three stories that constitute the History of the Thirteen, almost everyone who transgresses the spatial pattern, who moves into the wrong space at the wrong time, dies. Characters out of place disturb the ecological harmonies, pollute the moral order, and must pay the price. This makes the city a dangerous place, for it is far too easy to get lost in it, be swept away in its rushing stream, and end up in the wrong place. “I am convinced,” says Madame Jules in “Ferragus,” that “if I take one step into this labyrinth I shall fall into an abyss in which I shall perish.”37 A pure and perfect creature, Madame Jules ventures, out of filial devotion for Ferragus, her father, into a part of Paris inconsistent with her social status. “This woman is lost,” declares Balzac, because she has strayed into the wrong space. Contaminated, she finally dies of “some moral complication which has gone very far and which makes the physical condition more complex.” Auguste, Madame Jules’s admirer, is likewise ordained to die because “for his future misfortune, he scrutinized every storey of the building” that is Madame Jules’s secret destination. Ida Gudget, who looks after Ferragus and who dares to visit Jules in his bourgeois residence also dies.

Ferragus, Madame Jules’s father, is, however, a member of a secret society of men—known as the Thirteen—sworn to support each other in any and all of their endeavors. They are, says Balzac, equipped with wings. They “soar[ed] over society in its heights and depths, and disdained to occupy any place in it because they had unlimited power over it.” They are outside of and above the moral order because they cannot be located or placed. Sought by both Auguste and Jules (as well as by the police), Ferragus is never found. He appears only when and where he wants. He commands space while everyone else is trapped in it. This is a key source of his secret power.38

There is, however, an evolution in this perspective in Balzac’s work. The spatial rigidities that play a deterministic role in The History of the Thirteen become malleable in later works. As Sharon Marcus observes, Cousin Pons in the novel of that name (and one of the last that Balzac completed) is brought down by the concierge because she not only commands the place where Pons resides (she supplies him with his meals) but she also can construct a web of intrigue (using the “nerve system” of the concierge system) and forge a coalition of conspirators networked across the city to gain access to his apartment with its art collection.39 The capacity to command and produce space in this way is a power through which even the lowliest of people in society can subvert the spatial pattern and the moral order. Vautrin, the archcriminal-turned-police chief, thus uses his knowledge of the spatial ecology of the city and his capacity to command and control it to his own ends. The spatiality of the city is increasingly appreciated as dialectical, constructed, and consequential rather than passive or merely reflective.

In Paris there are certain streets which are in as much disrepute as any man branded with infamy can be. There are also noble streets; then there are streets which are just simply decent, and, so to speak, adolescent streets about whose morality the public has not yet formed an opinion. There are murderous streets; streets which are more aged than aged dowagers; respectable streets; streets which are always clean, streets which are always dirty; working class, industrious mercantile streets. In short, the streets of Paris have human qualities and such a physiognomy as leaves us with the impressions against which we can put up no resistance.40

These are hardly objective descriptions of individual streets. The hopes, desires, and fears of Balzac’s characters give meaning and character to the streets and to the neighborhoods they traverse. They may tarry at their leisure or feel the stress of incompatibility, but in no case can they ignore their situatedness. Balzac provides us with what the situationists later called a “psychogeography” of the streets and neighborhoods of the city. But he does so more from the perspective of his multiple characters than of himself.41 His characters even change their personas as they move from one locale to another. To enter into the Faubourg St. Germain (with all its aristocratic privilege) or merge with the chaos of the Palais Royale (with its motif of prostitution not only of women but also of literary talent to the seedy commercialism of journalism) places irresistible demands upon the participants. The only form of resistance is to move. Lucien, in Lost Illusions, fails to impress in the fashionable world of the Rue St Honoré (particularly after his disastrous showing at the Opera House), fails to master the sleazy world of publishing in the Palais Royale, and flees to the ascetic world of the Left Bank, close to the Sorbonne, where he adopts the persona of a penniless but ruthlessly honest student. There a tight circle of friends supports him in his worst moments. But when he moves in across town with the actress Coralie, who is infatuated with his good looks, Lucien accepts her judgment of his old habitat not only as a ghastly place of impoverishment but also as a denizen of simpletons. From his new perspective he even switches political positions and attacks the writings of his old friends.

Figure 18 Balzac was fascinated by the personalities and moods of Paris streets. This Marville photo from the 1850s captures some of the moodiness. It depicts the Street of Virtues which at the time was a center of prostitution. It ran into the Rue des Gravilliers, where the International Working Men’s Association was to set up its Paris headquarters in the 1860s.

We learn to understand the city from multiple perspectives. It is on the one hand an incomprehensible labyrinth of kaleidoscopic qualities: twirl the kaleidoscope around, and we see innumerable compositions and colorations of the urban scene. Yet there are persistent nodal points around which the image of the city coalesces into something more permanent and solid. The Faubourg St. Germain, the commercial world of the Right Bank boulevards, the stock exchange (“all rattle, bustle and harlotry”) and the Palais Royale, the rue St. Honoré, the student quarter around the Sorbonne, and the perpetual shadowy presence of working-class Paris (rarely invoked explicitly except in Cousin Bette, where both the infamous Petite Pologne and the Faubourg Sainte-Antoine are described in general terms, though one looks in vain throughout Balzac’s work for the depiction of any character who suffers all the indignities and insecurities of industrial employment). The legibility of the city is, furthermore, lit up by spectacles; the Opera, the theaters, the boulevards, the cafés, the monuments, and the parks and gardens again and again appearing as luminous points and lines within the fabric of the city, casting a net of meanings over urban life that would otherwise appear totally opaque. The boulevards in particular are the poetry through which the city primarily gets represented.

Armed with such pointers at street level, we can picture the totality from on high and learn to situate events and people within the labyrinthine and kaleidoscopic world of Parisian daily life. Consider, for example, how Balzac does this in the extraordinary opening passages of Old Goriot. “Only between the heights of Montmartre and Montrouge are there people who can appreciate” the scenes to follow. We look down first of all into “a valley of crumbling stucco and gutters black with mud, a valley full of real suffering and often deceptive joys.” Madame Vauquer’s lodging house stands on a street between the Val-de-Grace and the Pantheon, where

The absence of wheeled traffic deepens the stillness which prevails in these streets cramped between the domes of the Val-de-Grace and the Pantheon, two buildings that overshadow them and darken the air with the leaden hut of their dull cupolas.… The most carefree passer-by feels depressed, where even the sound of wheels is unusual, the houses gloomy, the walls like a prison. A Parisian straying here would see nothing around him but lodging houses or institutions, misery or lassitude, the old sinking into the grave or the cheerful young doomed to the treadmill. It is the grimmest quarter of Paris and, it may be said, the least known.

Likening this whole exercise to a descent into the catacombs, Balzac penetrates first into the neighborhood and then into house and garden, into rooms and people, with laserlike precision. A wicket gate by day and a solid door by night separate an enclosed garden from the street. The walls covered with ivy are also lined with espalier fruit trees and vines “whose pitted and dusted fruit is watched over anxiously by Madame Vauquer every year.” Along each wall “runs a narrow path leading to a clump of lime trees” under which there is “a round, green-painted table with some seats where lodgers who can afford coffee come to enjoy it in the dog days, even though it is hot enough to hatch eggs out there.” The three-story house “is built of hewn stone and washed with that yellow shade which gives a mean look to almost every house in Paris.” Within the house we encounter a depressing sitting room with its “boarding house smell” and an even more dismal dining room (the furniture is minutely and horribly described) where “everything is dirty and stained; there are no rags and tatters but everything is falling to pieces in decay.” And at the end of this depiction, we encounter the figure of Madame Vauquer herself, who

makes her appearance, adorned with her tulle cap, and shuffles about in creased slippers. Her ageing puffy face dominated by a nose like a parrot’s beak, her dimpled little hands, her body as plump as a church rat’s, her bunchy shapeless dress are in their proper setting in this room where misery oozes from the walls and hope, trodden down and stifled, has yielded to despair. Madame Vauquer is at home in its stuffy air, she can breathe without being sickened by it. Her face, fresh with the chill freshness of the first frosty autumn day, her wrinkled eyes, her expression, varying from the conventional set smile of the ballet-dancer to the sour frown of the discounter of bills, her whole person, in short, provides a clue to the boarding-house, just as the boarding-house implies the existence of such a person as she is.42

The consistency between environment and personality is striking. Viewed from on high, we can see Madame Vauquer and all the other inhabitants of the house not only in relation to Paris as a whole but also in terms of their distinctive ecological niches within the urban fabric. The ecology of the city and the personalities of its inhabitants are mirror images of each other.

Interiors play a distinctive role in Balzac’s work. The porosity of boundaries and the traffic that necessarily flows across them to sustain life in the city, in no way diminish the fierce struggle to limit access and to protect interiors from the penetration (the sexual connotations of that word are apt) by unwanted others into interior spaces. The vulnerability of apartment dwelling in this regard, as Marcus shows, provides a material terrain upon which such relations can most easily be depicted.43 Much of the action in Balzac’s novels is powered by attempts to protect oneself physically and emotionally against the threat of intimacy in a world where others are perpetually striving to penetrate, colonize, and overwhelm one’s interior life. Successful penetration invariably results in death of the victim, a final resting place in the cemetery, where all threat of intimacy is eliminated. Those (mainly women) who willingly give in to real love and intimacy suffer mortal consequences (sometimes sacrificially and even beatifically, like the reformed harlot, Lucien’s lover, in A Harlot High and Low). The desire for intimacy and the search for the sublime perpetually confront the mortal fear of its deadly consequences.

Balzac’s central criticism of the bourgeoisie, however, is that it is incapable of intimacy or inner feelings because it has reduced everything to the cold calculus and egoism of money valuations, fictitious capital, and the search for profit. Crevel, the crassest of Balzac’s bourgeois figures, seeks to procure the affections of his son’s mother-in-law at the beginning of Cousin Bette. But when Adeline finally gives in because she has been reduced to chronic indebtedness by her husband’s licentious profligacy, Crevel callously refuses, after elaborately and to Adeline’s face adding up the loss of rents on his capital that such a gesture would demand. The theme of intimacy and its dangers is pervasive. In The Girl with the Golden Eyes, Henri de Marsay is struck by the beauty of a woman he sees in the Tuileries. He pursues her ardently through protective walls and overcomes all manner of social and human barriers to gain access to her. Led blindfolded through mysterious corridors, he gains Paquita’s love in her hidden boudoir, which (like Madame Vauquer’s lodging house) tells us everything we need to know about her:

This boudoir was hung with red fabric overlaid with Indian muslin, its in-and-out folds fluted like a Corinthian column, and bound at top and bottom with bands of poppy-red material on which arabesque designs in black were worked. Under this muslin the poppy-red showed up as pink, the colour of love, repeated from the window curtains, also of Indian muslin, lined with pink taffeta and bordered with poppy-red fringes alternating with black. Six silver-gilt sconces, each of them bearing two candles, stood out from the tapestried wall at equal distances to light up the divan. The ceiling, from the centre of which hung a chandelier of dull silver-gilt, was dazzling white, and the cornice was gilded. The carpet was reminiscent of an Oriental shawl, reproducing as it did the designs and recalling the poetry of Persia, where the hands of slaves had worked to make it. The furniture was covered in white cashmere, set off by black and poppy-red trimmings. The clock and candelabra were of white marble and gold. There were elegant flower-stands full of all sorts of roses and white or red flowers.”44

In this intimate space De Marsay experiences “indescribable transports of delight,” and even becomes “tender, kind, communicative” as “he lost himself in those limbos of delight which common people so stupidly call ‘imaginary space’.” But Paquita knows she is doomed. “There was the terror of death in the frenzy with which she strained him to her bosom.” She tells him, “I am sure now that you will be the cause of my death.” When Henri, angered at the discovery of her involvement with another, returns with the idea of extracting her from that interior space in order to exact revenge, he finds her stabbed to death in a violent struggle with her woman lover, who turns out to be Henri’s long-lost half sister. Paquita’s “whole body, slashed by the dagger thrusts of her executioner, showed how fiercely she had fought to save the life which Henri had made so dear to her.” The physical space of the boudoir is destroyed and “Paquita’s blood-stained hands were imprinted on the cushions.”

In The Duchesse de Langeais the plot moves in the opposite direction but with similar results. Women protect themselves from intimacy by resorting to evasions, flirtations, calculated relationships, strategic marriages, and the like. General Montriveau is outraged at the way the Duchesse (who is married) trifles with his passions. He abducts her from a public space (a ball in progress) and conveys her to his inner sanctum, which has all the Gothic aura of a monk’s cell. There, in his own intimate space, he threatens to brand the Duchesse, to place the sign of the convict on her forehead (a fire flickers in the background and bellows sound ominously from an adjacent cell). The abducted Duchesse succumbs and declares her love as a soul in bondage—“a woman who loves always brands herself,” she says. Returned to the ball, the emotionally branded Duchesse ends up fleeing, after some unfortunate missed connections, to a remote chapel on a Mediterranean island, giving herself to God as Sister Thérèse. Montriveau finally tracks down his lost love many years later. His plan to abduct the nun succeeds exquisitely, but it is only her dead body that is retrieved, leaving him to contemplate a corpse “resplendent with the sublime beauty which the calm of death sometimes bestows on mortal remains.”45

Balzac extends this theme beyond relations between men and women. In The Unknown Masterpiece (which both Marx and Picasso intensely admired, though for quite different reasons) a talented apprentice is introduced to a celebrated painter but refused access to the inner studio where the masterwork is in progress. The painter wishes to compare the masterwork, a portrait, with a beautiful woman in order to satisfy himself that his painting is more lifelike than life itself. The apprentice sacrifices (and destroys the love of) his young lover by insisting (against her will) that she pose nude for the artist for purposes of comparison. In return, he is allowed inside the studio, full of wonderful paintings to see the masterpiece. But he finds the canvas almost blank. When he has the temerity to point this out, the old artist flies into a rage. That night the old artist kills himself, having first burned all his paintings.46

In Cousin Bette, a scheming relative of provincial and peasant origins inserts herself as intimate and angelic companion to the women of an aristocratic household only to destroy them. In Cousin Pons, the theme is repeated in reverse. Pons is a man whose sole identity in life is that of a collector of bric-a-brac. His collection is all that matters to him, but he has no idea how financially valuable it is. He protects it in the interior of his apartment. Penetration into this inner sanctum by a coalition of forces (led by the woman concierge who purports to look after him) brings about his death. Gaining illegal entry into Pons’s apartment, Balzac writes, “was tantamount to introducing the enemy into the heart of the citadel and plunging a dagger into Pons’s heart.”47 Pons does indeed die from consequences that flow from this incursion. But what, exactly, does he die of? In this case it is the penetration of commodity values into his private space; a space where the purity of values that animate Pons as a collector hitherto held sway. Benjamin surely had, or should have had, Pons in mind when he wrote:

The interior is the asylum where art takes refuge. The collector proves to be the true resident of the interior. He makes his concern the idealization of objects. To him falls the Sisyphean task of divesting things of their commodity character by taking possession of them. But he can bestow on them only connoisseur value, rather than use value. The collector delights in evoking a world that is not just distant and long gone but also better—a world in which, to be sure, human beings are no better provided with what they need than in the real world, but in which things are freed from the drudgery of being useful.48

So why value or desire intimacy in the face of such dangers? Why castigate women for their preference for the superficial and the social when to risk intimacy is to be branded with love or to embrace death? Why mock the bourgeoisie so mercilessly for its avoidance of intimacy at any cost? Intimacy is a human quality we can never do without, but is perpetually threatened by the relentless pursuit of exchange values. Balzac’s utopianism postulates a secure and pastoral place with a settled life of intimacy and valued possessions, secluded from the rough and tumble of the world and protected from commodification. But Balzac’s dream seems always destined, like Montriveau’s and the Duchesse’s love, to remain at best frustrated or, as in the case of Paquita and De Marsay, highly destructive.

This proposition is voiced directly in Cousin Pons. Madame Cibot, the concierge who leads the way into Pons’s apartment with such fatal consequences, dreams of using her ill-gotten wealth to retire to the country. But this she dare not do because the fortuneteller she consults warns her that she will suffer a violent death there. She lives out her days in Paris, deprived of the pastoral existence that she most desires. The bourgeoisie likewise stand condemned not because they avoid intimacy but because, given their pre-occupation with money values, they are incapable of it. But there is also something else at work here:

Paquita responded to the craving which all truly great men feel for the infinite, that mysterious passion so dramatically expressed in Faust, so poetically translated in Manfred, which urged Don Juan to probe deep into the heart of women, hoping to find in them that infinite ideal for which so many pursuers of phantoms have searched; scientists believe they can find it in science, mystics find it in God alone.49

Where does Balzac find it? By fleeing the intimacy of interior spaces into some wider exterior world or by experiencing through intimacy some kind of sublime moment of ecstasy that common people stupidly call “imaginary space”? Balzac oscillates between the two possibilities.

“In the whole work of Balzac,” remarks Poulet “nothing recurs so frequently as the proclamation of the annihilation of space-time by the act of mind.”50 Balzac writes: “I already had in my power the most immense faith, that faith of which Christ spoke, that boundless will with which one moves mountains, that great might by the help of which we can abolish the laws of space and time.” Balzac believed he could internalize everything within himself and express it through a supreme act of mind. He lived “only by the strength of those interior senses that constitute a double being within man.” Even though “exhausted by this profound intuition of things,” the soul could nevertheless aspire to be “in Leibniz’s magnificent phrase, a concentric mirror of the universe.”51 And this is precisely how Balzac constitutes his interiors. Pons’s interior is precious in the double sense that it is not only his but also a concentric mirror of a European universe of artistic production. Paquita’s boudoir exerts its fascination because it is redolent of the exoticism associated with the Orient, the Indies, the slave girl, and the colonized woman. Montriveau’s room to which the Duchesse de Langeais is forcibly abducted internalizes the ascetic sense of Gothic purity associated with a medieval monk’s cell. The interior spaces all mirror some aspect of the external world.

The annihilation of space and time was a familiar enough theme in Balzac’s day. The phrase may have derived from a couplet of Alexander Pope’s: “Ye Gods! annihilate but space and time / And make two lovers happy.”52 Goethe deployed the metaphor to great effect in Faust, and by the 1830s and 1840s the idea was more broadly associated with the coming of the railroads. The phrase then had widespread currency in both the United States and Europe among a wide range of thinkers contemplating the consequences and possibilities of a world reconstructed by new transport and communication technologies (everything from the canals and railroads to the daily newspaper, which Hegel had already characterized as a substitute for morning prayer). Interestingly, the same concept can be found in Marx (latently in the Communist Manifesto and explicitly in the Grundrisse). Marx uses it to signify the revolutionary qualities of capitalism’s penchant for geographical expansion and acceleration in the circulation of capital. It refers directly to capitalism’s penchant for periodic bouts of “time-space compression.”53

In Balzac, however, the idea usually depicts a sublime moment outside of time and space in which all the forces of the world become internalized within the mind and being of a monadic individual. It “flashes up” as a moment of intense revelation, the religious overtones of which are hard to miss (and Balzac’s dalliance with religion, mysticism, and the powers of the occult is frequently in evidence). It is the moment of the sublime (a favored word of Balzac’s). But it is not a passive moment. The blinding insight that comes with the annihilation of space and time allows for a certain kind of action in the world. In The Quest of the Absolute, Marguerite, after a furious argument with her father, reacts as follows:

When he had gone, Marguerite stood for a while in dull bewilderment; it seemed as if her whole world had slipped from her. She was no longer in the familiar parlour; she was no longer conscious of her physical existence; her soul had taken wings and soared to a world where thought annihilates time and space, where the veil drawn across the future is lifted by some divine power. It seemed to her she lived through whole days between each sound of her father’s footsteps on the staircase; and when she heard him moving above in his room, a cold shudder went through her. A sudden warning vision flashed like lightening through her brain; she fled noiselessly up the dark staircase with the speed of an arrow, and saw her father pointing a pistol at his head.54

A sublime moment of revelation outside of space and time allows one both to grasp the world as a totality and to act decisively in it. Its connection to sexual passion and possession of “the other” (a lover, the city, nature, God) is unmistakable (as indicated in the original Pope couplet). But it allows Balzac a certain conceptual power, without which his synoptic vision of the city and of the world would be impossible. The dealer who yields the wild ass’s skin to Raphael asks “how could one prefer all the disasters of frustrated desires to the superb faculty of summoning the whole universe to the bar of one’s mind, to the thrill of being able to move without being throttled by the thongs of time or the fetters of space, to the pleasure of embracing and seeing everything, of leaning over the edge of the world in order to interrogate the other spheres and listen to the voice of God?”55 Raphael, it transpires, was raised in a household where “the rules of time and space were so rigorously applied” as to be totally oppressive. He is therefore deeply attracted to that “privilege accorded the passions which gives them the power to annihilate space and time.” The trouble is that every expression of desire shrinks the skin and brings Raphael closer to death. His only possible response is to adopt a time-space discipline that is far more rigorous than anything his father imposed. Since movement is a function of desire, Raphael has to seal himself up in space and impose a strict temporal order upon himself and those around him in order to avoid any expression of desire.56

Figure 19 Balzac’s emphasis upon the annihilation of space and time was very much associated, in the 1830s and 1840s, with the coming of the railways. The punch line of this Daumier cartoon from 1843–1844 on “impressions and compressions,” is that it is obvious that when the train moves forward, the passengers must go backward.

The perpetual bourgeois desire to reduce and eliminate all spatial and temporal barriers would then appear as a secular version of this revolutionary desire. Balzac elaborates upon these mundane aspects of bourgeois business practices. “The crowd of lawyers, doctors, barristers, business men, bankers, traders on the grand scale,” he says, must “devour time, squeeze time” because “time is their tyrant; they need more, it slips away from them, they can neither stretch nor shrink it.” The drive to annihilate space and time is everywhere apparent:

Man possesses the exorbitant faculty of annihilating, in relation to himself, space which exists only in relation to himself; of utterly isolating himself from the milieu in which he resides, and of crossing, by virtue of an almost infinite locomotive power, the enormous distances of physical nature. I am here and I have the power to be elsewhere! I am dependent upon neither time, nor space, nor distance. The world is my servant.57

The ideal of annihilation of space and time suggests how a distinctively capitalistic and bourgeois version of the sublime is being constituted. The conquest of space and time and the mastery of the world (of Mother Earth) appear, then, as the displaced but sublime expression of sexual desire in innumerable capitalistic fantasies. Something vital is here revealed about the bourgeois myth of modernity. For Balzac, however, the collapse of time future and time past into time present is precisely the moment at which hope, memory, and desire converge. “One triples present felicity with aspiration for the future and recollections of the past,” he wrote. This is the supreme moment of personal revelation and social revolution, a sublime moment that Balzac loves and fears.

The fantasy of a momentary annihilation of space and time allows Balzac to construct an Archimedean position from which to survey and understand the world, if not change it. He imagines himself “riding across the world, disposing all in it to my liking.… I possess the world effortlessly, and the world hasn’t the slightest hold upon me.” The imperial gaze is overt: “I was measuring how long a thought needs in order to develop itself; and compass in hand, standing upon a high crag, a hundred fathoms above the ocean, whose billows were sporting among the breakers, I was surveying my future, furnishing it with works of art, just as an engineer, upon an empty terrain, lays out fortresses and palaces.”58 The echo from Descartes’s engineer as well as from Goethe’s Faust is unmistakable. The dialectical relations between motion and stasis, between flows and movements, between interiors and exteriors, between space and place, between town and country, can all be investigated and represented.

Balzac is out to possess Paris. But he respects and loves it too much as a “moral entity,” as a “sentient being,” to want merely to dominate it. His desire to possess is not a desire to destroy or diminish. He needs the city to feed him images, thoughts, and feelings. He cannot treat of it as a dead object (as Haussmann and Flaubert, each in his own way, later did). Paris has a personality and a body. Paris, “the most delightful of monsters,” is often depicted as a woman (playing opposite Balzac’s male fantasies): “Here a pretty woman, farther off a poverty-stricken hag; here as freshly minted as the coin of a new reign, and in another corner of the town as elegant as a lady of fashion.” Paris is “sad or gay, ugly or beautiful, living or dead; for [devotees] Paris is a sentient being; every individual, every bit of a house is a lobe in the cellular tissue of that great harlot whose head, heart and unpredictable behaviour are perfectly familiar to them.” But in its cerebral functions, Paris takes on a masculine personality as the intellectual centre of the globe, “a brain teeming with genius which marches in the van of civilization; a great man, a ceaseless creative artist, a political thinker with second sight.”59

The end product is a synoptic vision, encapsulated in extraordinary descriptions of the physiognomy and personality of the city (such as those that open The Girl with the Golden Eyes). Again and again we are urged to see the city as a totality, and graspable as such. Consider this passage from “Ferragus”:

Paris again with its streets, shop signs, industries and mansions as seen through diminishing spectacles: a microscopic Paris reduced to the tiny dimensions of shades, ghosts, dead people.… Jules perceived at his feet, in the long valley of the Seine, between the slopes of Vaugirard and Meudon, those of Belleville and Montmartre, the real Paris, wrapped in the dirty blue veil engendered by its smoke, at that moment diaphanous in the sunlight. He threw a furtive glance over its forty thousand habitations and said, sweeping his arm over the space between the column of the Place Vendôme and the gilded cupola of the Invalides: “there it is that she was stolen from me, thanks to the baneful inquisitiveness of this crowd of people which mills and mulls about for the mere pleasure of milling and mulling about.60

Rastignac, at the end of Old Goriot, standing in that same cemetery:

saw Paris spread out below on both banks of the winding Seine. Lights were beginning to twinkle here and there. His gaze fixed almost avidly upon the space that lay between the Column of the Place Vendôme and the Dome of the Invalides; there lay the splendid world that he wished to conquer. He eyed that humming hive with a look that foretold of its despoliation, as if he already felt on his lips the sweetness of the honey, and said with superb defiance: “it’s war, between us two.”61

This synoptic vision echoes through the century. Haussmann, armed with balloons and triangulation towers, likewise appropriated Paris in his imagination as he set out to reshape it on the ground. But there is an important difference. Whereas Balzac obsessively seeks to command, penetrate, dissect, and then internalize everything about the city as a sentient being within himself, Haussmann converts that fantastic urge into a distinctive class project in which the state and the financiers take the lead in techniques of representation and of action. Intriguingly, Zola in La Curée replicates the perspective of Jules and Rastignac, but now it is the speculator, Saccard, who plans to profit from slashing through the veins of the city in an orgy of speculation (see pp. 116, 122).