That man’s physical and spiritual life is linked to nature means simply that nature is linked to itself, for man is a part of nature.

—MARX

Haussmannization did not leave the pastoral longings of Balzac’s utopianism unrequited. Nor did it ignore the legitimacy to be conferred by appeal to the medieval, Gothic, and Christian origins of the French state (the architect and great restorer of Gothic cathedrals, Viollet-le-Duc, twice decorated Notre Dame, once (hurriedly) to celebrate the declaration of Empire and once, at Haussmann’s invitation, to celebrate Louis Napoleon’s marriage). Haussmann also responded to the emphasis upon health and hygiene, upon the revitalization of the human body and the psyche through access to the curative powers of “pure” nature, which had lain behind a series of proposals made by the “hygienists” of the 1830s. And he acted upon proposals, most explicitly laid out by Meynadier in 1843, for parks and open spaces within the city (to function as the “lungs” of the city). Personally dedicated to dealing with these issues, Haussmann invited his talented advisers (particularly Alphand and Belgrand) to come up with remedies. The Bois de Boulogne (known as a “pitiless desert” during the July Monarchy and a particular object of Louis Napoleon’s interest for revitalization), Vincennes, Luxembourg, the spectacular Buttes Chaumont (carved out of a garbage dump), Parc Monceau, and even smaller spaces such as the Square du Temple were either created from scratch or completely reengineered, mostly under Alphand’s creative guidance, to bring a certain concept of nature into the city.

It was, of course, a constructed concept of nature that was at work here, and it was fashioned according to very distinctive criteria. Grottoes and waterfalls, lakes and rustic places to dine, restful walks and bowers, were all craftily engineered within these distinctive spaces of the city, emphasizing pastoral and arcadian visions, Gothic designs and romantic conceptions of the restorative powers of access to a pristine, nonthreatening (therefore tamed), but still purifying nature.1 These strategies served several purposes. They brought “the spectacle of nature” into the city and thereby contributed to the luster of the imperial regime. They also co-opted the politicized romanticism of the 1840s and sought to transform it into a passive and more contemplative relation to nature within the open spaces of the city.

Figure 85 The opening up of neighborhoods to sunlight and fresh air allows this inhabitant, as Daumier records it, to know whether the plant he is growing will be a rose or a gillyflower.

There was much in this that appealed to a distinctive cultural tradition, common to both workers and bourgeois alike, that stretched back at least to the Restoration if not before. But this was not an autonomous cultural development that had no relation to the evolving paths of capitalism.2 The commodification of nature (and of access to nature) and the spreading influence of finance capital and credit had much to do with developments during the July Monarchy. Concerns over the consequences of overcrowding, insalubrity, and the casualization of an increasingly impoverished labor force—all products of what Marx called “the manufacturing” period of capitalist development that typically preceded machinery and modern industry—had brought the question of the relation to nature center stage during the Restoration and after. Romanticism (of the Lamartine and Georges Sand variety) and pastoral utopianism (of the sort that Balzac articulated) were both in part a response and a reaction to these degraded conditions of urban life. The Fourierists were particulary emphatic about restoring the relation to nature as a central tenet of their utopian plans. In a more practical register, the hygienists of the July Monarchy (Villermé, Frègier, and Parent-Duchatalet) produced more and more evidence of the vile living conditions in which much of the urban population in both Paris and the provinces were confined. While they looked to cleanliness and public health measures as remedies (particularly for the scourge of cholera), there was plenty of grist in these reports to feed sentiments that varied from Fourierist disgust with the failures of civilization to a romantic longing for return to some healthier relation to living nature. The conditions that gave rise to such sentiments had everything to do with the gathering pace of capitalist development.

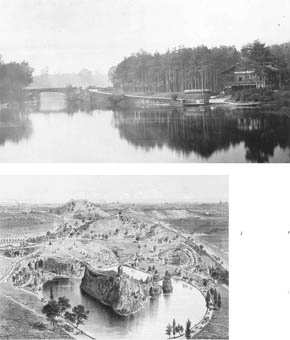

Figure 86 The transformation of the Bois de Boulogne from a “pitiless desert” under the July Monarchy into a site of pastoral image (above, in Marville’s photo) accompanied by innumerable Gothic touches was one of Alphand’s supreme achievements, along with the extraordinary reengineering of the old city dump to make the spectacular park of Buttes Chaumont (below, by Charpentier and Benoist).

Figure 87 The redesign of the Square du Temple (which conveniently erases all popular memory of the place where the King and his family were imprisoned for several months before their executions in 1793) brought vegetation and running water into the very heart of the city. It actually combined the park by Alphand, a mairie by Hittorff, and a covered market by Baltard into a total re-orchestration of an urban space around leisure, administration, and the market.

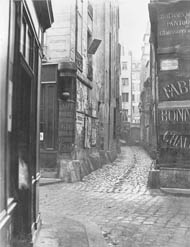

Figure 88 Most of Marville’s photos of old Paris seem to have been taken shortly after a rain shower, for there are invariably runnels of liquid in the street. But these runnels are, for the most part, indicators of raw sewage. Much work was needed to remedy this unhealthy situation.

Haussmann, as was his wont, altered the scale of the response to these questions, and thereby changed the stakes in the remedies he produced:

In 1850 there were forty-seven acres of municipal parks. When he was forced from office, twenty years later, there were 4,500 acres. He added eighteen squares to the city—an additional seven in the annexed zone—and nearly doubled the number of trees lining avenues and boulevards, with some of the grander streets given a double row of trees on each side. In addition he planted trees on all public land.… The greening of Paris was a political act for Haussmann.3

This was the era of the chestnut with its spring blossoms and its fall foliage. If Alphand provided the genius for overall design (particularly of the Bois de Boulogne), then the horticulturalist he summoned from Bordeaux, Barillet-Deschamps, provided innumerable romantic touches for those who ventured into the parks and squares of the city.

With respect to water and sewage, however, Haussmann had very little choice, because it was obvious in 1850 that Paris lagged far behind British and American cities, and even some of the other cities of Europe (such as Berlin), in its level of provision. The disgusting conditions described by Fannie Trollope during her visit in 1835 had scarcely been touched by 1848. “But great and manifold as are the evils entailed by the scarcity of water in the bedrooms and kitchens of Paris,” she wrote, “there is another deficiency greater still and infinitely worse in its effects. The want of drains and sewers is the great defect of all the cities in France and a tremendous defect it is.”4 Most of Marville’s street photos of the 1850s make it seem as if it has just stopped raining, but the runnels visible in the streets are signs of raw sewage, not rainwater. The cholera outbreak of 1848–1849 and another in 1855 raised the stakes even higher, for though the causes were not yet known, it was generally presumed that insalubrious conditions had much to do with it.

Figure 89 The new sewers were wide and spacious enough (top, by Valentin) for the bourgeoisie and visiting royalty to be taken on tours of them (bottom, by Pelcoq). The tours were partly designed to reassure the bourgeoisie that there were no sinister forces, of the sort that Hugo had described in Les Misérables, lurking underground.

The story of Haussmann’s reshaping of Paris underground has been told many times over, and it is generally applauded as dramatic, spectacular, and even heroic.5 Water provision certainly improved. In 1850 Paris had a daily inflow of twenty-seven million gallons, which amounted to twenty-six gallons a day per inhabitant if it had been distributed equally (which it was not). By 1870 this was increased to fifty gallons a day per inhabitant (still far less than London), with works in hand that would shortly raise it to sixty-four. On the distribution side Haussmann was less successful. Half the houses did not have running water in 1870, and the distribution system to commercial establishments was weakly articulated. Belgrand, with Haussmann’s support, also decided to separate the supply of drinking water from nonpotable water for the fountains, street cleaning, and industrial uses. Initially, this helped reduce the costs of provision of fresh potable water. But the struggle to identify and procure adequate supplies of fresh potable water of good quality in the Paris region was drawn out and beset by many technical difficulties. Haussmann emerged victorious. Fittingly, the aqueducts that brought pure water from the springs of Dhuis and Vanne some distance from Paris could be modeled on those of imperial Rome, and thus contribute in their own way to the propagation of an imperial aura. They came to Paris at sufficient height, furthermore, to allow the whole city to be serviced by gravitational flow.

Increased flows of water entailed paying more attention to sewage disposal. It was still the case in 1850 that the street was the main sewer. In 1852 (before Haussmann) the prefecture had already directed that “sewer hookups be installed in all new buildings and buildings undergoing major renovation on streets with sewers.” But to be effective, this required that all Paris streets have sewers. Haussmann’s response was typical. “While the length of city streets doubled during the Second Empire (from 424 kms to 850 kms) the sewer system grew more than fivefold (from 143 kms to 773 kms).”6 Even more important, the sewers constructed were capacious enough to house easily repaired water pipes and other underground infrastructures (electricity cables in later times). Paris underground became a spectacle to behold. Tours were laid on for visiting dignitaries and a bourgeoisie hitherto fearful of all that lay underground, including the low species of underclass life that lurked there (Hugo’s famous description of the Paris sewers in Les Misérables emphasized that idea). In a rather famous passage in his report to the Municipal Council, Hausmann wrote:

These underground galleries would be the organs of the metropolis and function like those of the human body without ever seeing the light of day. Pure and fresh water, along with light and heat, would circulate like the diverse fluids whose movement and replenishment sustain life itself. These liquids would work unseen and maintain public health without disrupting the smooth running of the city and without spoiling its exterior beauty.7

Gandy interprets this as a discursive throwback to premodern conceptions (of nature as alive rather than as dead) and sets out to show how “the circulatory dynamics of economic exchange were to overwhelm organic conceptions of urban order and institute a new set of relationships between nature and urban society.”8 This, he argues, was not accomplished by Haussmann, but had to wait until the end of the nineteenth century. Haussmann’s language here may of course just have been tactical, drawing upon the long tradition of biological reasoning and organic metaphors that suffused the work of the hygienists of the July Monarchy, but it is just as likely that, at a moment when mechanical engineering language was not settled upon as the technical language of modernity, he was drawn to the metaphor of circulation and metabolism as a purely practical matter (much as contemporary environmentalists have revived the concept of metabolism as fundamental to the idea of sustainable urban development). The careful scientific inquiries and reports of Belgrand, and the memoranda that Haussmann produced to persuade a skeptical and always cautious Municipal Council, are largely devoid of such organic rhetoric, and analyze matters in a mechanical way. They do, however, emphasize the idea of circulation, and this metaphor did double duty. On the one hand, it could emphasize the cleansing functions of the free circulation of air, of sunlight, of water, and of sewage in the construction of a healthy urban environment at the same time that it evoked a connection with the free circulation of money, people, and commodities throughout the city, as if these were also entirely natural functions. The circulation of capital could thereby be rendered “natural” and the reshaping of the metropolis (its boulevards, park spaces, squares, and monuments) could be interpreted as in accord with natural design.