Mankind … inevitably sets itself only such tasks as it is able to solve, since closer examination will always show that the problem itself arises only when the material conditions for its solution are already present or at least in the course of formation.

—MARX

“When the imperial mantle finally falls on the shoulders of Louis Bonaparte,” Marx predicted in 1852, “the bronze statue of Napoleon will crash from the top of the Vendôme Column.”1 On May 16, 1871, the hated symbol collapsed before a Communard crowd, temporarily diverted from the threatening gunfire of the forces of reaction encircling Paris. Between the prediction and the event lay eighteen years of “ferocious farce.”

The ferocity had dual, sometimes complementary, but in the end conflictual, origins. The Empire, to protect both itself and the civil society over which it reigned, resorted to an arbitrariness of state power that touched everyone, from the street entertainers hounded off the boulevards to the bankers excluded from the lucrative city loan business. But the accelerating power of the circulation and accumulation of capital was also at work, transforming labor processes, spatial integrations, credit relations, living conditions, and class relations with the same ferocity that it assumed in the creative destruction of the Parisian built environment. In the aftermath of 1848, the arbitrariness of state power appeared to be a crucial prop to private property and capital. But the farther the Empire degenerated into open farce, the more evident it became that modernity could not be produced out of imperial tradition, that there was and could be no stable class basis of imperial power, and that the supposed omnipotence of government sat ill with the omniscience of market rationality. The schism between the Saint-Simonians and the liberal political economists therefore symbolized a deep antagonism between political and economic processes.

Napoleon III’s strategy for maintaining power was simple: “Satisfy the interests of the most numerous classes and attach to oneself the upper classes.”2 Unfortunately, the explosive force of capital accumulation tended to undermine such a strategy. The growing gap between the rich (who supported the Empire precisely because it offered protection against socialistic demands) and the poor led to mounting antagonism between them. Every move the Emperor made to attach to the one simply alienated the other. Besides, the workers remembered as fact (adorned with growing fictions) that there had once been a Republic that they had helped to produce and that had voiced their social concerns. The demand for liberty and equality in the market also tended to emphasize a republican political ideology within segments of the bourgeoisie. This was as much at odds with the authoritarianism of Empire as it was antagonistic to plans for the social republic.

Figure 99 Daumier’s view of the history of the Second Empire has the traditional feminine figure of Liberty bound hand and foot and placed between the cannons of the coup d’état of 1851 and those of the Emperor’s defeat at Sedan in 1870.

Figure 100 The toppling of the Vendôme Column by the Communards occurred on May 16th, 1871. In this photo by Braquehais, the painter Courbet (who was later ordered to pay for the reconstruction of the column out of his own pocket) may well be the middle figure among those at the back. The column had a checkered history. Chaudet’s imperial statue (made from captured Austrian canon) was taken off and melted down with the restoration of the monarchy in 1815, and used to remake the destroyed statue of Henry IV on the Pont-Neuf. The figure of Napoleon as Caesar was replaced atop the column by a simple fleur-de-lis. The July Monarchy, anxious to link itself to the revolution and Napoleon’s populism, put Napoleon back on top of the column in 1834, but as a citizen-soldier in a campaign cloak. In 1863, Seurre’s representation was replaced by Dumont’s figure of Napoleon as Caesar, in antique dress and holding a Roman symbol of victory. This was the version toppled by the Communards.

The split between political and social conceptions of the Republic—so evident in 1848—continued to be of great significance. It could be and was used to great effect to divide and rule. But that gave no secure class basis to political power. The Empire was, however, so caught up in the maelstrom of capitalistic progress that it could not satisfy the traditionalists and the conservatives (particularly the Catholics) who objected to the new materialism and the new class configurations that were in the course of formation. The consensus behind imperial authority was hard to sustain and threatened to evaporate entirely when problems of overaccumulation and devaluation once more arose. The contradictions of capitalist growth were therefore matched by unstable political lurchings from this or that side of the class spectrum or from this or that faction. When, in 1862, the Emperor honored James Rothschild with a visit to his country house (to the immense chagrin of the Pereires), and when, in the same year, he granted two hundred thousand francs to workers to send their elected delegates to London (where Karl Marx so eagerly awaited them and from whence they returned to form the Paris branch of the First International), something was plainly amiss. Such shifting, far from alleviating matters, only added anxiety about what was to replace the Empire if and when it should fall.

The monarchists, though extremely powerful, offered no real alternative. Divided among themselves, they gathered around them ultraconservative Catholics, traditionalists, and almost every reactionary sentiment antagonistic to capitalistic progress. With a strong base in rural France, their influence in Paris tended to shrink during the Second Empire and in the end was confined mainly to the very traditional salons of the aristocratic Left Bank. While the Empire had its supporters, particularly among the finance capitalists, state functionaries, and bourgeois property owners of western Paris who were well satisfied with Haussmann’s works, the centers of business, commerce, and professional services (like law) on the Right Bank became bastions of republicanism, usually tempered by pragmatic financial opportunism that gave the Empire many opportunities to co-opt them. The Café de Madrid on the Boulevard Montmartre was the geopolitical meeting point of this kind of republicanism with the more déclassé and sometimes bohemian sentiments of writers drawn to that area as a center of press and communications power. The republicanism of the Left Bank was of a rather different order. The product of students and academics, it was less pragmatic and more revolutionary and utopian, capable of spinning off in all kinds of directions into alliances with workers and artisans or into its own forms of revolutionary and conspiratorial politics. Working-class Paris, sprawled in a vast peripheral zone from northwest through the east to southwest (with its thickest concentration in the northeast), was solidly republican, but with strong social concerns and not a few resentments at the betrayal suffered at the hands of bourgeois republicanism in 1848.

The struggle that unfolded in Paris during the 1860s and presaged the Commune was of epic proportions. It was a struggle to give political meaning to concepts of community and class; to identify the true bases of class alliances and antagonisms; to find political, economic, organizational, and physical spaces in which to mobilize and from which to press demands. It was, in all these senses, a geopolitical struggle for the transformation of the Parisian economy, as well as of the city’s politics and culture.

The parting of the ways between capital and Empire was not registered by dramatic confrontation but by the slow erosion of the organic links between them. The counterattack of Parisian property owners against the conditions of expropriation, the resistance of the Bank of France to the cheap credit that the Saint-Simonians sought, the growing resentment of industrialists at Haussmann’s harassment, and the increasing domination of small owners and shopkeepers by finance capital signaled growing disaffection of this or that fragment of the bourgeoisie. Though some, like the property owners, partially returned to the imperial fold, others were more and more alienated. Ironically, the more successfully the Empire repressed the workers, the freer the bourgeois opposition felt to express itself. Yet the more that opposition grew, the greater the political space within which workers could operate. On the one hand, bourgeois republican rhetoric shielded them, while on the other, the growth of bourgeois opposition forced the Empire to curry the workers’ favor as part of its populist base.

Figure 101 Daumier here depicts one of the minor contradictions facing the “good bourgeois” at a time when they were facing many serious political complications.

The reconstruction of the republican party was one of the most signal achievements of the Second Empire. And while it depended upon the coming together of many different currents of opinion in many parts of the country, what happened in Paris was crucial. Powerfully but incoherently implanted within the liberal professions (which saw the Republic perhaps as a means to acquire an autonomous class power) and with strong potential support in business, industry, and commerce, bourgeois republicanism needed a much sharper definition than it had achieved in 1848. The rambunctious, explosive image of femininity on the barricades had to be corseted, tamed, and made thoroughly respectable. The déclassé republicanism of students, intellectuals, writers, and artists had somehow to be confronted and controlled. But the bourgeois republicans also needed working-class support if they were to succeed. How to gain that support without making any but the mildest concessions to social conceptions of the Republic that typically threatened private property, money power, the circulation of capital, and even patriarchy and the family was the fledgling republican party’s most pressing problem. On questions of political liberty, legality, freedom of expression, and representative government (locally, as in the nation), it was possible to make common cause. Bourgeois republicans therefore tried to keep such issues at the center of political debate. Questions of freedom of association, workers’ rights, and representation were touchier. And debate over the social republic had to be buried within a reformist rhetoric on relatively safe questions like improved education. Bourgeois republicanism tended to become violent in its defense of patriarchy and vicious in its attitudes toward socialism. But the terms of alliance with the working class always had to be open to negotiation at the same time that the battle between social and political conceptions of the Republic had to be fought out unto death, as it turned out, in the bloodbath of the Commune.

The revival of working-class politics in the early 1860s initially rested upon the reassertion of traditional institutional rights. The mutual benefit societies, in spite of imperial regulation, had early become the legal front for all kinds of covert worker organization. Their direct subversion into trade union forms (they were at the root of most strike activity) provoked innumerable prosecutions in the 1850s. But their indirect use for political purposes was quite uncontrollable. Herein lay, for example, the significance of funerals, since this was a key benefit and brought all members together to listen to a graveside discourse that often became a political speech. The Empire became less willing to attack the mutual benefit societies because it increasingly needed them as a means to canvass and to mobilize working-class support. There is considerable evidence that associations and coalitions existed in practice without prosecution by the early 1860s.3 The mutual benefit societies became centers of consciousness formation and means for organizing the collective expression of demands. The corporatist forms hidden within them became more explicit as craft workers sought to protect themselves against the ravages of technological and organizational change and the flood of unskilled immigration. This use of the mutual benefit frame had important effects. It helped bridge the separation between working and living, and preserved a unity of concern for production and consumption questions. In the context of Parisian industry, it also reinforced the search for alternatives down mutualist, cooperative paths. Both consciousness and political action were to draw much of their strength from that sense of unity.

The wave of institution-building and modernization, upon which later administrations were to draw, became most marked after 1862. The Emperor, under increasing attack from upper-class royalists in alliance with conservative Catholics and threatened on the other flank by the revival of bourgeois republicanism, was forced to seek support from a working class that even his own prefects were telling him was in dire straits. But imperial initiatives to draw workers to the side of industrial progress and Empire sparked little grassroots response save a lengthy explanation from Tolain, which earned him an interview with the Emperor and the right to form a workers’s commission made up of presidents of mutual benefit societies, thus recognizing the latter’s de facto corporatist and professional role. Ironically, the commission meetings began at the very moment of one of the first major strikes of Parisian craft workers, that of the printers in 1862. The printers’ leaders were imprisoned for the crime of coalition, even though public sympathy (including that of many republicans) was with them. When the Emperor pardoned them, he in effect rendered the laws against coalition and association moot. He did so as the workers he had helped send to the fateful London exposition were returning, telling tales of better working conditions and wages achieved in Britain through trade unions.

But, curiously, neither side was yet willing to recognize the realities of class struggle. The opening given to working-class politics in the early 1860s initially provoked a wave of mutualist sentiments. The mutual benefit societies flourished in numbers and membership, while schemes for mutual credit (such as the Credit au Travail), consumer cooperatives (two founded in 1864), and cooperative housing burst out all over (some even drew the Emperor’s private support). The International’s statutes were approved by the government in 1864. At the same time, the Empire engaged Emile Ollivier (later to head the liberal Empire of 1869) to rewrite the law on combinations. The law, designed to avoid organized class struggle, gave the working class the right to strike but not the right to organize or assemble. The bookbinders and bronze workers, followed by the stonecutters, promptly celebrated by striking for shorter hours without wage reductions. But the labor movement’s main focus was on organizing rights and conditions of labor rather than on wage levels in the early 1860s. Proudhon was, at this point, at the height of his influence, inveighing against strikes and unions (he almost seemed to approve of Ollivier’s law) and pushing for mutualist worker democracy (as well as for all women to return to the domestic sphere, where they belonged). The French delegates to the International’s meetings of 1866 in Geneva, led by Tolain, carried with them a veritable charter for Proudhonism and mutualism, thus testifying to the deep hold of such ideas over craft worker consciousness.

The workers’ movement had its setbacks, too. Attempts to create an independent workers’ press were quickly quashed, in part through bourgeois republican opposition. The attempt to define an independent political space likewise failed. In 1864 the craft workers, with some radical republican support, issued the Manifesto of the Sixty, which focused on workers’ rights as a political issue. The general effect was to raise the fearful specter of class struggle and provoke the unfounded but not unreasonable suspicion that the workers’ movement was being used by the Empire to frustrate bourgeois republican aspirations. When Tolain, a signer of the Manifesto and a founder of the Parisian branch of the International, ran as an independent workers’ candidate in 1863 to emphasize the distinctiveness of the workers’ cause, he was vilified in the republican press and so squeezed by opposition from that quarter that he received fewer than five hundred votes in a parliamentary election that saw the bourgeois republicans sweep to power in much of Paris.

The recession of 1867–1868 marked a radical realignment of class forces as well as a turning point in worker militancy and rhetoric. What became known as the “millionaires’ strike” saw the massive accumulation of surplus capital in the coffers of the Bank of France, stagnation in public works and in the upper-class Parisian property market, and fiercer international competition and rising unemployment in the face of strongly rising prices. The downfall of the Pereires, a jittery stock market, and the growing likelihood of geopolitical conflict with Prussia undermined the sense of security that the authoritarianism of Empire had earlier been able to impart. The spectacle of the 1867 Universal Exposition diverted attention at one level, though many noted the irony that it celebrated the commodity fetish and consumerism at a time of shrinking real incomes, and that it brought competitive commodities as well as the king of Prussia into the very heart of Paris at a time of heightened international competition and geopolitical tension.

The workers’ movement then became much more militant and switched to real wages rather than organizational rights as its main focus of concern. Within the International this was marked by the eclipse of the mutualists like Tolain and Fribourg and their replacement by communists like Varlin and Malon, whose attitudes, given their youth, were less affected by memories of 1848 and more forged out of the actualities of class conflict through the 1860s. The persecution of the International at that point only helped the process of transition by removing the original leaders, giving it greater and greater credibility among Parisian workers, and forcing it into the underground, where it encountered militant Blanquists—themselves turning to the organization of the working class as part of their revolutionary strategy. Yet even though Varlin, for one, moved rapidly to a more and more collectivist politics, striving to organize and federate unions into agents of mass working-class action, he still clung to certain mutualist principles of organization as the basis for the transition to socialism.4 The craft workers straddled the ambiguity between class organization and mutualism without, apparently, being too aware of the tension between them.

The year 1867 saw important strikes by bronze workers (supported for the first time by international funds), tailors, and construction workers oriented primarily toward higher wages. In that same year generalized discontent over living standards spilled over into street demonstrations that touched the unorganized and unskilled workers. For the first time since 1848, the unorganized of Belleville descended into the space of inner-city craft workers to express their discontent. Barricades appeared sporadically, only to be swept away by the forces of order almost immediately. The bourgeoisie was not beguiled, either, by the important concessions made to it. The return to quasi-parliamentary government (symbolized by the restoration of the speaker’s tribune in the legislature) opened up a forum for complaint. And there was much to complain about. The free-speech movement of the early 1860s had already turned the Left Bank into a hotbed of student and intellectual unrest. Industrialists complained about Haussmann, and workshop masters and shopkeepers complained fiercely about conditions of credit and the power of the grand monopolies that the state had done so much to support. The recession and Prussia’s defeat of Austria at Sadoya (to say nothing of the unhappy Mexican venture) shook the confidence of everyone in a government that had come to power on the promise of peace and prosperity, and that now looked like it could not deliver on either. Those bourgeois like Thiers who had long felt excluded from the grand feast of state wealth and power stood ready to mobilize the agitation and unrest to their own advantage. Even the monarchists could find causes, like that of decentralization, around which they sought to rally popular discontent.

All of this was mere prelude to the awesome struggles of 1868–1871. But it was an important prelude because it posed the question of what class alliance could emerge that would be capable of replacing the Empire. Could the monarchists wean away enough support from the bourgeois center to stymie the republican thrust? Could the bourgeois republicans control the working-class movement to keep the political republic out of the clutches of the socialists? Could the radical freethinkers and déclassé republicans enter into alliance with a workers’ movement that overcame its craft worker bias and reached out to encompass the unskilled and thus create a revolutionary and socialist republic? Could the Empire divide and rule and manipulate each and every one of these factions through co-optation and its police and provocateur power? In practice, the Empire was forced into more and more concessions. It relaxed press censorship (May 1868) and permitted public meetings on “nonpolitical” topics (June 1868). The right to form unions was conceded in 1869. But the state in no way relinquished its powers of provocation and repression.

The International’s leaders looked to collaborate with the republican bourgeois opposition, and were promptly arrested as early as the end of 1867. The respectable republicans ignored the call for a class alliance. The workers were equally critical of such a tactic, since they remembered only too well how the political republic had betrayed them in 1848. The second wave of the International’s leaders sought an independent space within which they could build the strength of their own movement. Varlin led the bookbinders’ mutual benefit society and transformed it into a vigorous and coherent union in 1869. He helped to found an extensive system of consumer cooperatives (La Marmite) in 1867, bringing cheap food, politics, and consumption together in a more coherent way than the wineshop or the cabaret, which the mass of workers who lived in boardinghouses otherwise patronized. He vigorously defended equal rights for women in the workplace and within workers’ organizations. He headed the movement to federate the numerous Parisian unions (perhaps twenty thousand strong) in 1869 and played a leading role in the International’s efforts to unify working-class action over national and international space. It was exactly such a broad geopolitical conception of the struggle that terrified the “honest bourgeois.” The problem for Varlin was to integrate the restless mass of unorganized and unskilled workers into a movement that had always had a craftworker base. The scaffolding he and others had erected by 1870 was by no means sufficient to that task. Recognizing that weakness, he sought tactical alliances with the radical and often revolutionary fringe of the bourgeoisie.

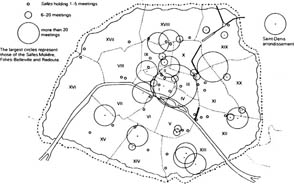

Figure 102 The location and frequency of public meetings in Paris, 1868–1870.

There had always been such a fringe within la bohème and within the student movement. The Blanquists had set about organizing such discontent around their own program. But the relaxation of press censorship revealed a much wider swath of disaffection. Rochefort, a newspaper proprietor, became the instant hero of the popular and disaffected classes with La Lanterne, a newspaper full of radical critique and revolutionary rhetoric (which earned Rochefort periodic stays in jail and which horrified the conservative bourgeoisie). Recognizing the power of this movement, Varlin established a tactical alliance to try to ensure that social questions were properly integrated into any radical republican program. The radical republicans, for their part, had to erase the memory of betrayal in 1848. They made the attempt in 1868 by recalling the death of a republican representative, Baudin, on the barricades of 1851. They proposed a massive pilgrimage to his tomb on the Day of the Dead. The government tried to bar their way, and those who did get into the cemetery of Montmartre had a hard time finding the grave. Hence there arose the idea of a public subscription. The government’s prosecution of those engaged in the affair only drew more attention to the “crime” of the coup d’état while allowing a young lawyer, Gambetta, to become another instant hero of the radical cause. The symbolic resurrection of Baudin, the creation of tradition, was, in a way, a stroke of genius. It focused on the illegitimacy of Empire in such a way as to symbolize the bourgeois role in the heart of the space of worker struggle (this was the special virtue of the cemetery of Montmartre). It was by gestures of this sort that the radical bourgeoisie reached out to embrace the “other Paris” in symbolic unity.

The “nonpolitical” public meetings, which began on June 28, 1868, were extraordinary affairs. Heavily concentrated in the zones of disaffection, no amount of government surveillance could prevent them from turning into occasions for mass education and political consciousness-raising.5 The geopolitics was highly predictive of the Commune. Not only were the meetings unevenly spread across the Parisian space, but specialization of audience, topic, and place was quickly established. The political economists and bourgeois reformers who looked to the meetings as opportunities for mass education about their cause were outgunned and often shouted down in the meeting halls of the “other Paris.” An assortment of radicals, feminists, socialists, Blanquists, and other revolutionaries dominated what became regular political theater in many quarters of the city. The political economists and reformers were forced to withdraw to the relative safety of the Left Bank and Right Bank center, leaving the north and northeast of the city entirely to the radicals, socialists, and revolutionaries. It seemed that the “other Paris” was now the exclusive space for popular political agitation. That trend was reinforced by a sudden resurgence of popular street culture, revolutionary songs and ballads suddenly bursting from a murky underground where they had lain dormant for almost two decades.

This kind of agitation was as disturbing to the respectable bourgeois as it was to the supporters of Empire. Could the Empire rally the disaffected in the name of law and order? Only if it made major concessions. The year 1869 therefore began with official disavowal of Haussmann’s slippery financing in the face of fiscally conservative bourgeois critics. The appearance of Jules Ferry’s severe attack on the prefect in the Comptes Fantastiques d’Haussmann in 1868 charged him with all kinds of improprieties. The aftermath was curious. First, it forced Haussmann to reduce public works activities and depressed the construction trade and Parisian industry even further, thus exacerbating social discontent. Second, none of those who attacked him denied the utility of his works, and many of them pleaded for completion of this or that part of his project in 1869 or, like Rothschild, were only too happy to lend the city money as it needed it. It increasingly appeared that Haussmann was a mere surrogate target for the Emperor and that the exclusivity of his seeming patronage was what was at stake.

The subsequent election campaign of May 1869 was surrounded with political agitation. A riot ensued when Ollivier tried to take the theme of support for liberal Empire into the center of Paris. The crowd at Châtelet moved noisily to the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, the traditional hearth of revolution, before dispersing. The next day a crowd of twenty thousand moved around the craft worker quarters; and the day after that a crowd of fifteen thousand tried to move from the Sorbonne, where it had assembled, to the Bastille, but found its way blocked. During this phase, Haussmann’s boulevards were turned into a battleground. Hitherto appropriated by bourgeois strollers and consumers, they were suddenly taken over by a surging mass of discontented workers, students, shopkeepers, and street people. On June 12 a crowd even penetrated as far as the Opéra and set up the first real barricade. The bourgeois response was to try and reassert their rights to boulevard space by chasing off undesirables. Even the Emperor saw the symbolic value of passing along the contested terrain between the Opéra and the Port-Saint-Denis, though he was greeted with glacial silence as he passed.

Figure 103 Haussmann’s fall was accompanied by a campaign to discredit his creative accounting, amid speculation to the effect that he had robbed the public treasury. In this cartoon by Mailly he is branded as a thief, as the man who sold Paris for purposes of destruction. There is little evidence, however, that he personally profited from the works he set in motion.

But the crowds upon the boulevards hid secrets. It was never clear, for example, whether the violent agitations and the “white blouses” were signs of secret police activity or not. Certainly, they had abundant opportunities to stir up threats to law and order and scare the respectable bourgeois back into the imperial fold. It was never clear, either, just how revolutionary in spirit the crowds were. Large crowds of twenty thousand or more frequently dispersed when asked to do so by law-abiding republicans. And the huge demonstration of over one hundred thousand people, which assembled after the Emperor’s nephew shot a radical journalist, Victor Noir, dispersed quietly at Rochefort’s request rather than confront the forces of order that barred their way into central Paris. Yet the day before, Rochefort had more than hinted that the day of revolution was near. The Blanquists had also wanted to start the insurrection at that moment, but found little support. The times were very unsettled but the leadership was uncertain. Could the ambiguity and dispersal of opposition sentiment be overcome and transformed into revolution?

The elections of May and June 1869 indicated otherwise. Only in Belleville was a radical sympathizer elected, and Gambetta was a politician who could bridge moderate socialist and left bourgeois opinion with skill and authenticity. Elsewhere, the political republicans swept the board; it even took a very conservative Thiers to narrowly overcome the Empire’s candidate in the bourgeois west. The plebiscite a year later was harder to interpret, but the abstentions (urged by the radical left) did not increase markedly, and although the “no” votes prevailed, the Empire still received a surprising number of affirmative votes. It would take, it seemed, a much more thorough organization and education of the popular classes to bring the social republic into being. And it was exactly on such a task that the socialists spent their efforts. The public meetings provided a basis for neighborhood organizations, while the themes broached there encouraged the formation of trade unions, consumer cooperatives, producers’ cooperatives, feminist organizations, and the like. These formed the organizational infrastructure that would be used to such good effect in the Commune. And there is no question as to their revolutionary political orientation, though there was much room for disagreement, interpersonal feuds, and neighborhood conflicts. But this form of opposition had a different orientation than that on the streets. Strikes in commerce, tanning, and woodworking, and the building of links between unions and neighborhoods, proceeded with a different rhythm and had more definite targets at the same time that they were relatively more immune to police infiltration. Here was the grand dividing line between the socialists, who urged the patient building of a revolutionary movement, and the Blanquists, who looked to spontaneous, violent insurrection.

But by 1870 it was plain that the mass of the bourgeoisie was looking for a legal way out of the impasse of Empire, was shifting away from any coalition with the “reds.” And it used its ownership and influence within the press to hammer home the message of law and order to workers and petite bourgeoisie alike. The discontent, however, daily became more threatening as living conditions deteriorated and the economy stagnated. Conflict in Belleville in February 1870 left several dead, many arrested, and considerable property damage (usually that of unpopular shopkeepers and landlords). A major strike at the locomotive works at Cail signaled a level of anger as well as worker organization that had hitherto not been apparent. The ferment of discontent seemed uncontainable as the Empire lost its nerve and the bourgeoisie held its ground. Though conditions were desperate, the International’s leaders (unlike the Blanquists’) thought the political conditions were not yet ripe for social revolution. They were, as the Commune was to show only too well, right in that judgment. What is extraordinary is how far, wide, and deep they had ranged in the construction of a revolutionary organization capable of uniting many disparate elements within the dispersed space of Paris (as well as France). The tragedy, in the end, was that a conjuncture of events forced them to put their efforts on the line so prematurely in defense of a losing cause. That conjuncture was less accidental, however, than might be supposed. For all the signs were there that the “honest bourgeois”—led by Thiers—not only were concerned to have done with Empire and seize the fruits of political power but also were determined to have done with the “reds” once and for all and to subject them to their own vile brand of “final solution.” Thus was the final act of ferocious farce left until that bloody week in May 1871 when some thirty thousand Communards died.

Figure 104 The strike of the workers at the large factory of Cail in 1870 was both extensive enough and significant enough to make it into the bourgeois press.

Exactly what happened in the Commune is beyond our ken. But much of it was rooted in the processes and effects of the transformation of Paris in the Second Empire. The organization of municipal workshops for women; the encouragement given to producer and consumer cooperatives; the suspension of the night work in the bakeries; and the moratorium on rent payments, debt collections, and the sale of items from the municipal pawnshop at Mont-de-Piété reflected the sore points that had bothered working-class Paris for years. The assemblies of craft workers; the strengthening of unions; the vigor of the neighborhood clubs that grew out of the public meeting places of 1868–1870 and that were to play a crucial role in the defense of quarters; the setting up of the Union of Women; and the attempt to pull together working political organizations that bridged the tensions between centralization and decentralization, between hierarchy and democracy (the Committee of the Twenty Arrondissements, the Central Committee of the National Guard, and the Commune itself) all testified to the vigorous pursuit of new organizational forms generated from the nexus of the old. The creation of a Ministry of Labor and strong measures toward free and nonreligious primary and professional education testified to the depth of social concern.

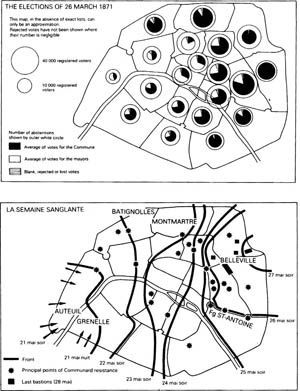

But the Commune never challenged private property or money power in earnest. It requisitioned only abandoned workshops and dwellings, and prostrated itself before the legitimacy of the Bank of France (an episode that Marx and Lenin noted well). The majority sought principled and mutually acceptable accommodation rather than confrontation (even some of the Blanquists in practice went in that direction). But much of the opposition to the Commune was also given. The schism between the “moderate” republican mayors of the arrondissements (who got short shrift in Versailles when they tried to mediate) and the Commune grew as tensions rose. The bourgeoisie, which had deigned to remain to brave the rigors of the Prussian siege of 1870, quickly showed its teeth in mobilizing the “Friends of Order” demonstration of March 21 and 22, 1871, and thereafter turned western Paris into an easy point of penetration for the forces of reaction. The map of voting patterns for the Commune was predictable enough. The difference this time was that hegemonic power now lay with a worker-based movement.

Thiers’s decision to relocate the National Assembly from Bordeaux to Versailles after signing a humiliating surrender to the Prussians, and his withdrawal of all executive functions from Paris after his failure to disarm Paris on March 18, 1871, crystallized the forces of rural reaction in a way that the Commune’s faint calls for urban and rural solidarity could not match. His mobilization of rural ignorance and fear, fed by vicious propaganda, into an army prepared to give no quarter (were they not charged, after all, with chasing the red devils out of a sinful and atheistic Paris?), showed he meant to have a cathartic resolution, come what may. Once the possibility of a quick, preemptive strike against Versailles was lost, there was little the Commune could do except await its fate. The stress of that brought out divisions and fed interior discontents and rivalries within the uneasy class and factional alliance that produced the Commune. Splits between radical bourgeois, each armed with his own splendid theory of revolution; between practical patriots and peddlers of rhetoric and dreams; between workers bewildered by events and leaders of craft unions trying to render consistent and compelling interpretations; between loyalties to quarter, city, and nation; between centralizers and decentralizers, all gave the Commune an air of incoherence and a political practice riddled with internal conflict. But such divisions had been long in the making; their roots lay deep in tradition, and their evolution had been confused by the turn to capitalist modernity and the clash between the politics of Empire and the economy of capital. Once more, as Marx had written in the Eighteenth Brumaire, “The tradition of all the dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brain of the living,” but this time it was the working-class movement that internalized the nightmare. The Commune was a high price to pay to discredit pure Proudhonism and the pure Jacobinism drawn from the reconstructed spirit of 1789. The tragedy was that an alternative modernity, one that was central to what the Commune was striving for, was killed in the womb of a bourgeois society that never looked beyond the political to the social republic as a potential fulfillment of its aspirations.

Figure 105 The elections of March 26, 1871, and the phases of reoccupation of Paris during the “bloody week” of May 1871 illustrate all too clearly the east-west imbalance in political affiliations within the city. The low number of voters in the west reflects the fact that many of the more affluent citizens of the city had fled to their rural retreats.

The Commune was a singular, unique, and dramatic event, perhaps the most extraordinary of its kind in capitalist urban history. It took war, the desperation of the Prussian siege, and the humiliation of defeat to light the spark. But the raw materials for the Commune were put together by the slow rhythms of the capitalist transformation of the city’s historical geography. I have tried in this work to lay bare the complex modes of transformation in the economy and in social organization, politics, and culture that altered the visage of Paris in ineluctable ways. At each point along the way, we find people like Thiers and Varlin, like Paule Minck and Jules Michelet, like Haussmann and Louis Lazare, like Louis Napoleon, Proudhon, and Blanqui, like the Pereires and the Rothschilds, swirling within the crowd of street singers and poets, ragpickers and craft workers, bankers and prostitutes, domestics and idle rich, students and grisettes, tourists, shopkeepers, and pawnbrokers, cabaret owners and property speculators, landlords, lawyers, and professors. Somehow all were contained within the same urban space, occasionally confronting each other on the boulevards or the barricades, and all of them struggling in their own ways to shape and control the social conditions of their own historical and geographical existence. That they did not do so under historical and geographical conditions of their own choosing is self-evident. The Commune was produced out of a search to transform the power and social relations within a particular class configuration constituted within a particular space of a capitalist world that was itself in the full flood of dramatic transition. We have much to learn from the study of such struggles. And there is much to admire, much that inspires there, too.