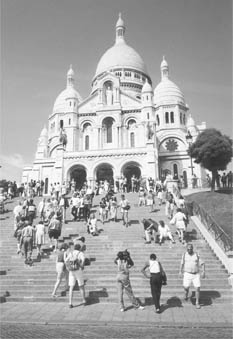

Strategically placed atop a hill known as the Butte Montmartre, the Basilica of Sacré-Coeur occupies a commanding position over Paris. Its five white marble domes and the campanile that rises beside them can be seen from every quarter of the city. Occasional glimpses of it can be caught from within the dense and cavernous network of streets that makes up old Paris. It stands out, spectacular and grand, to the young mothers parading their children in the Jardins de Luxembourg, to the tourists who painfully plod to the top of Notre Dame or who painlessly float up the escalators of the Centre Beaubourg, to the commuters crossing the Seine by metro at Grenelle or pouring into the Gare du Nord, to the Algerian immigrants who on Sunday afternoons wander to the top of the rock in the Parc des Buttes Chaumont. It can be seen clearly by the old men playing boule in the Place du Colonel Fabien, on the edge of the traditional working class quarters of Belleville and La Villette—places that have an important role to play in our story.

On cold winter days when the wind whips the fallen leaves among the aging tombstones of the Père Lachaise cemetery, the basilica can be seen from the steps of the tomb of Adolphe Thiers, first president of the Third Republic of France. Though now almost hidden by the modern office complex of La Défense, it can be seen from more than twenty kilometers away in the Pavillion Henry IV in St. Germain-en-Laye, where Adolphe Thiers died. But by a quirk of topography, it cannot be seen from the famous Mur des Fédérés, in that same Père Lachaise cemetery, where, on May 27, 1871, some of the last few remaining soldiers of the Commune were rounded up after a fierce fight among the tombstones and summarily shot. You cannot see Sacré-Coeur from that ivy-covered wall now shaded by an aging chestnut. That place of pilgrimage for socialists, workers, and their leaders is hidden from a place of pilgrimage for the Catholic faithful by the brow of the hill on which stands the grim tomb of Adolphe Thiers.

Figure 106 The Basilica of Sacré-Coeur

Few would argue that the Basilica of Sacré-Coeur is beautiful or elegant. But most would concede that it is striking and distinctive, that its distinctive and unique style achieves a kind of haughty grandeur that demands respect from the city spread out at its feet. On sunny days it glistens from afar, and even on the gloomiest of days its domes seem to capture the smallest particles of light and radiate them outward in a white marble glow. Floodlit by night, it appears suspended in space, sepulchral and ethereal. Thus does Sacré-Coeur project an image of saintly grandeur, of perpetual remembrance. But remembrance of what?

The visitor drawn to the basilica in search of an answer to that question must first ascend the steep hillside of Montmartre. Those who pause to catch their breath will see spread out before them a marvelous vista of rooftops, chimneys, domes, towers, monuments—a vista of old Paris that has not changed much since that dull and foggy October morning in 1872 when the archbishop of Paris climbed that steep slope. When he reached the top, the sun miraculously chased both fog and cloud away to reveal the splendid panorama of Paris spread out before him. The archbishop marveled for a moment before crying aloud: “It is here, it is here where the martyrs are, it is here that the Sacred Heart must reign so that it can beckon all to it!”1 So who are the martyrs commemorated here in the grandeur of this basilica?

The visitor who enters that hallowed place will most probably first be struck by the immense painting of Jesus that covers the dome of the apse. Portrayed with arms stretched wide, the figure of Christ bears an image of the Sacred Heart upon his breast. Beneath, two words stand out directly from the Latin motto—GALLIA POENITENS. And beneath this stern admonition that “France Repents,” stands a large gold casket containing the image of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, burning with passion, suffused with blood, and surrounded with thorns. Illuminated day and night, it is here that pilgrims come to pray. Opposite a life-size statue of Saint Marguerite Marie Alacoque, at the entry to the basilica, words from a letter written by that saintly person—date, 1689; place, Paray-le-Monial—tell us more about the cult of the Sacred Heart:

THE ETERNAL FATHER WISHING REPARATION FOR THE BITTERNESS AND ANGUISH THAT THE ADORABLE HEART OF HIS DIVINE SON HAD EXPERIENCED AMONG THE HUMILIATIONS AND OUTRAGES OF HIS PASSION DESIRES AN EDIFICE WHERE THE IMAGE OF THIS DIVINE HEART CAN RECEIVE VENERATION AND HOMAGE.

Prayer to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, which, according to the Scriptures, had been exposed when a centurion thrust a lance through Jesus’ side during his suffering upon the cross, was not unknown before the seventeenth century. But Marguerite Marie, beset by visions, transformed the worship of the Sacred Heart into a distinctive cult within the Catholic Church. Although her life was full of trials and suffering, her manner severe and rigorous, the predominant image of Christ that the cult projected was warm and loving, full of repentance and suffused with a gentle mysticism.2 Marguerite Marie and her disciples set about propagating the cult with great zeal. She wrote to Louis XIV, for example, claiming to bring a message from Christ in which the King was asked to repent, to save France by dedicating himself to the Sacred Heart, to place its image upon his standard, and to build a chapel to its glorification. It is from that letter of 1689 that the words now etched in stone within the basilica are taken.

The cult diffused slowly. It was not exactly in tune with eighteenth-century French rationalism, which strongly influenced modes of belief among Catholics, and it stood in direct opposition to the hard, rigorous, and self-disciplined image of Jesus projected by the Jansenists. But by the end of the eighteenth century it had some important and potentially influential adherents. Louis XVI privately took devotion to the Sacred Heart for himself and his family. Imprisoned during the French Revolution, he vowed that within three months of his deliverance he would publicly dedicate himself to the Sacred Heart and thereby save France (from what, exactly, he did not say, nor did he need to). And he vowed to build a chapel for the worship of the Sacred Heart. The manner of Louis XVI’s deliverance did not permit him to fulfill that vow. Marie Antoinette did no better. The queen delivered up her last prayers to the Sacred Heart before keeping her appointment with the guillotine.

These incidents are of interest because they presage an association, important for our story, between the cult of the Sacred Heart and the reactionary monarchism of the ancien régime. This put adherents to the cult in firm opposition to the principles of the French Revolution. Believers in the principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity, who were in any case prone to awesome anticlerical sentiments and practices, were, in return, scarcely enamored of such a cult. Revolutionary France was no safe place to attempt to propagate it. Even the bones and other relics of Marguerite Marie, now displayed in Paray-le-Monial, had to be carefully hidden during those years.

The restoration of the monarchy in 1815 changed all that. The Bourbon monarchs sought, under the watchful eye of the European powers, to restore whatever they could of the old social order. The theme of repentance for the excesses of the revolutionary era ran strong. Louis XVIII did not fulfill his dead brother’s vow to the Sacred Heart, but he did build, with his own moneys, the Chapel of Expiation on the spot where his brother and his family had been so unceremoniously interred—GALLIA POENITENS.

A society for the propagation of the cult of the Sacred Heart was founded, however, and proceedings for the glorification of Marguerite Marie were transmitted to Rome in 1819. The link between conservative monarchism and the cult of the Sacred Heart was further consolidated, and the cult spread among conservative Catholics. But it was still viewed with some suspicion by the liberal, progressive wing of French Catholicism. But now another enemy was ravaging the land, disturbing the social order. France was undergoing the stress and tensions of capitalist industrialization. In fits and starts under the July Monarchy, and then in a great surge in the early years of the Second Empire of Napoleon III, France saw a radical transformation in certain sectors of its economy, in its institutional structures, and in its social order. From the standpoint of conservative Catholics, this transformation threatened much that was sacred in French life, since it brought within its train a crass and heartless materialism, an ostentatious and morally decadent bourgeois culture, and a sharpening of class tensions. The cult of the Sacred Heart now assembled under its banner not only those devotees drawn by temperament or circumstance to the image of a gentle and forgiving Christ, not only those who dreamed of a restoration of the political order of yesteryear, but also all those who felt threatened by the materialist values of the new social order, in which money had become the Holy Grail, the papacy of finance capital threatened the authority of the Pope, and mammon threatened to supplant God as the primary object of worship.

To these general conditions, French Catholics could also add some more specific complaints in the 1860s. Napoleon III had finally come down (after considerable vacillation) on the side of Italian unification, committing himself politically and militarily to the liberation of the central Italian states from the temporal power of the Pope. The latter did not take kindly to such politics and under military pressure retired to the Vatican, refusing to come out until his temporal power was restored. From that vantage point, the Pope delivered searing condemnations of French policy and the moral decadence which, he felt, was sweeping over France. In this manner he hoped to rally French Catholics in the active pursuit of his cause. The moment was propitious. Marguerite Marie was beatified by Pius IX in 1864, and the cult of the Sacred Heart became a rallying cry for all forms of conservative opposition. The era of grand pilgrimages to Paray-le-Monial, in the south of France, began. The pilgrims, many carried to their destination by the new railroads that the barons of grand finance had helped to build, came to express repentance for both public and private transgressions. They repented for the materialism and decadent opulence of France. They repented for the restrictions placed upon the temporal power of the Pope. They repented for the passing of the traditional values embodied in an old and venerable social order. GALLIA POENITENS.

Just inside the main door of the Basilica of Sacré-Coeur in Paris, the visitor can read the following inscription:

THE YEAR OF OUR LORD 1875 THE 16TH JUNE IN THE REIGN OF HIS HOLINESS POPE PIUS IX IN ACCOMPLISHMENT OF A VOW FORMULATED DURING THE WAR OF 1870–71 BY ALEXANDER LEGENTIL AND HUBERT ROHAULT DE FLEURY RATIFIED BY HIS GRACE MSGR. GUIBERT ARCHBISHOP OF PARIS; IN EXECUTION OF THE VOTE OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF THE 23RD JULY 1873 ACCORDING TO THE DESIGN OF THE ARCHITECT ABADIE; THE FIRST STONE OF THIS BASILICA ERECTED TO THE SACRED HEART OF JESUS WAS SOLEMNLY PUT IN PLACE BY HIS EMINENCE CARDINAL GUIBERT. …

Let us flesh out that capsule history and find out what lies behind it. As Bismarck’s battalions rolled to victory after victory over the French in the summer of 1870, an impending sense of doom swept over France. Many interpreted the defeats as righteous vengeance inflicted by divine will upon an errant and morally decadent France. It was in this spirit that Empress Eugénie was urged to walk with her family and court, all dressed in mourning, from the Palace of the Tuileries to Notre Dame, to publicly dedicate themselves to the Sacred Heart. Though the Empress received the suggestion favorably, it was, once more, too late. On September 2, Napoleon III was defeated and captured at Sedan; on September 4, the Republic was proclaimed on the steps of the Hôtel de Ville and a Government of National Defense was formed. On that day also Empress Eugénie took flight from Paris, having prudently, and at the Emperor’s urging, already packed her bags and sent her more valuable possessions on to England.

The defeat at Sedan ended the Empire but not the war. The Prussian armies rolled on, and by September 20 they had encircled Paris and put that city under a siege that was to last until January 28 of the following year. Like many other respectable bourgeois citizens, Alexander Legentil fled Paris at the approach of the Prussian armies and took refuge in the provinces. Languishing in Poitiers and agonizing over the fate of Paris, he vowed in early December that “if God saved Paris and France and delivered the sovereign pontiff, he would contribute according to his means to the construction in Paris of a sanctuary dedicated to the Sacred Heart.” He sought other adherents to this vow, and soon had the ardent support of Hubert Rohault de Fleury.3 The terms of Legentil’s vow did not, however, guarantee it a very warm reception, for, as he soon discovered, the provinces “were then possessed of hateful sentiments towards Paris.” Such a state of affairs was not unusual, and we can usefully digress for a moment to consider its basis.

Under the ancien régime, the French state apparatus had acquired a strongly centralized character that was consolidated under the French Revolution and Empire. This centralization thereafter became the basis of French political organization and gave Paris a peculiarly important role in relation to the rest of France. The administrative, economic, and cultural predominance of Paris was assured. But the events of 1789 also showed that Parisians had the power to make and break governments. They proved adept at using that power and were not loath, as a result, to regard themselves as privileged beings with a right and a duty to foist all that they deemed “progressive” upon a supposedly backward, conservative, and predominantly rural France. The Parisian bourgeoisie, of no matter what political persuasion, tended to despise the narrowness of provincial life (even though they often depended upon the rents they accrued there to live comfortably in the city) and found the peasant disgusting and incomprehensible. From the other end of the telescope, Paris was generally seen as a center of power, domination, and opportunity. It was both envied and hated. To the antagonism generated by the excessive centralization of power and authority in Paris were added all of the vaguer small town and rural antagonisms toward any large city as a center of privilege, material success, moral decadence, vice, and social unrest. What was special in France was the way in which the tensions emanating from the “urban-rural contradiction” were so intensely focused upon the relation between Paris and the rest of France.

Under the Second Empire these tensions sharpened considerably. Paris experienced a vast economic boom as the railways made it the hub of a process of national spatial integration. The city was brought into a new relationship with an emerging global economy. Its share of an expanding French export trade increased dramatically, and its population grew rapidly, largely through a massive immigration of rural laborers. Concentration of wealth and power proceeded apace as Paris became the center of financial, speculative, and commercial operations. The contrasts between Parisian wealth and dynamism and, with a few exceptions (such as Marseille, Lyon, Bordeaux, and Mulhouse), provincial lethargy and backwardness became more and more marked. Furthermore, the contrasts between affluence and poverty within the city became ever more startling and were increasingly expressed in terms of a geographical segregation between the affluent bourgeois quarters of the west and the working-class quarters of the north, east, and south. Belleville became a foreign territory into which the bourgeois citizens of the west rarely dared to venture. The population of that place, which more than doubled between 1853 and 1870, was pictured in the bourgeois press in the most denigrating and fearful of terms. As economic growth slowed in the 1860s and as the authority of Empire began to fail, Paris became a cauldron of social unrest, vulnerable to agitators of any stripe. And to top it all, Haussmann, as we have seen, had embellished Paris with spacious boulevards, parks, and gardens, monumental architecture of all sorts. He had done this at immense cost and by the slipperiest of financial means, a feat that scarcely recommended itself to the frugal provincial mind. The image of public opulence that Haussmann projected was matched by the conspicuous consumption of the bourgeoisie, many of whom had grown rich speculating on the benefits of Haussmann’s state-financed improvements.

Small wonder, then, that provincial and rural Catholics were in no frame of mind to dig into their pockets to embellish Paris with yet another monument, no matter how pious its purpose. But there were even more specific objections that emerged in response to Legentil’s proposal. The Parisians had with their customary presumptuousness proclaimed a republic when provincial and rural sentiment was heavily infused with monarchism. Furthermore, those who had remained behind to face the rigors of the siege were showing themselves remarkably intransigent and bellicose, declaring they would favor a fight to the bitter end, when provincial sentiment showed a strong disposition to end the conflict with Prussia. And then the rumors and hints of a new materialist politics among the working class in Paris, spiced with a variety of manifestations of revolutionary fervor, gave the impression that the city had, in the absence of its more respectable bourgeois citizenry, fallen prey to radical and even socialist philosophy. Since the only means of communication between a besieged Paris and the nonoccupied territories was pigeon or balloon, abundant opportunities arose for misunderstanding, which the rural foes of republicanism and the urban foes of monarchism were not beyond exploiting.

Legentil therefore found it politic to drop any specific mention of Paris in his vow. But toward the end of February 1871 the Pope endorsed it, and from then on, the movement gathered some strength. And so on March 19, a pamphlet appeared that set out the arguments for the vow at some length.4 The spirit of the work had to be national, the authors urged, because the French people had to make national amends for what were national crimes. They confirmed their intention to build the monument in Paris. To the objection that the city should not be further embellished, they replied, “Were Paris reduced to cinders, we would still want to avow our national faults and to proclaim the justice of God on its ruins.”

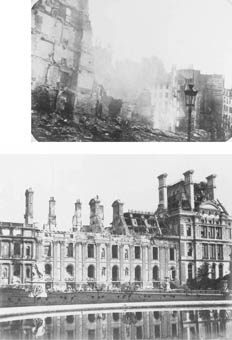

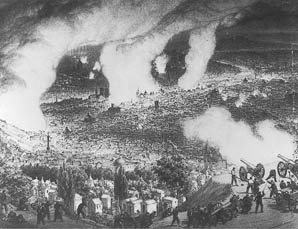

Figure 107 The fires that raged in Paris during the closing days of the Commune left behind an enormous train of destruction. Among the many photos available (mostly anonymous), we find one of the Rue Royale with the fires still smoldering. Many of the major public buildings, such as the Hotel de Ville, the Ministry of Finance, and the Palace of the Tuileries were reduced to ruins. The palace was eventually torn down by the Republican administration that came to power in the 1880s, in part because of the cost to rebuild it, but also because it was a hated symbol of royal and Napoleonic power.

The timing and phrasing of the pamphlet proved fortuitously prophetic. On March 18, Parisians had taken their first irrevocable steps toward establishing self-government under the Commune. The real or imagined sins of the Communards were subsequently to shock and outrage bourgeois and, even more vociferously, provincial opinion. And since much of Paris was indeed reduced to cinders in the course of a civil war of incredible ferocity, the notion of building a basilica of expiation upon these ashes became more and more appealing. As Rohault de Fleury noted, with evident satisfaction, “In the months to come, the image of Paris reduced to cinders struck home many times.”5 Let us rehearse a little of that history.

The origins of the Paris Commune lie in a series of events that ran into each other in complex ways. Precisely because of its political importance within the country, Paris had long been denied any representative form of municipal government and had been directly administered by the national government. For much of the nineteenth century, a predominantly republican Paris was chafing under the rule of monarchists (either Bourbon “legitimists” or “Orléanists”) or authoritarian Bonapartists. The demand for a democratic form of municipal government, often referred to by all parties, as we have seen, as a “commune,” was long-standing and commanded widespread support within the city.

The Government of National Defense set up on September 4, 1870, was neither radical nor revolutionary, but it was republican.6 It also turned out to be timid and inept. It labored under certain difficulties, of course, but these were hardly sufficient to excuse its weak performance. It did not, for example, command the respect of the monarchists and lived in perpetual fear of the reactionaries of the right. When the Army of the East, under General Bazaine, capitulated to the Prussians at Metz on October 27, the general left the impression that he did so because, being monarchist, he could not bring himself to fight for a republican government. Some of his officers who resisted the capitulation saw Bazaine putting his political preferences above the honor of France. This was a matter that was to dog French politics for several years. Rossel, who was later to command the armed forces of the Commune for a while (and who was to be arbitrarily sentenced to death and executed for so doing), was one of the officers shocked to the core by Bazaine’s evident lack of patriotism.7

But the tensions between the different factions of the ruling class were nothing compared to the real or imagined antagonisms between a traditional and remarkably obdurate bourgeoisie and a working class that was beginning to find its feet and assert itself. Rightly or wrongly, the bourgeoisie was greatly alarmed during the 1860s by the emergence of working-class organization and political clubs, by the activities of the Paris branch of the International Working Men’s Association, by the effervescence of thought within the working class and the reemergence of anarchist and socialist philosophies. And the working class—although by no means as well organized or as unified as its opponents feared—was certainly displaying abundant signs of an emergent class consciousness.

The Government of National Defense could not stem the tide of Prussian victories or break the siege of Paris without widespread working-class support. And the leaders of the left were only too willing to give it in spite of their initial opposition to the Emperor’s war. Blanqui promised the government “energetic and absolute support,” and even the International’s leaders, having dutifully appealed to the German workers not to participate in a fratricidal struggle, plunged into organizing for the defense of Paris. Belleville, the center of working-class agitation, rallied spectacularly to the national cause, all in the name of the Republic.8

The bourgeoisie sensed a trap. They saw themselves, wrote a contemporary commentator drawn from their ranks, caught between the Prussians and those whom they called “the reds.” “I do not know,” he went on, “which of these two evils terrified them most; they hated the foreigner but they feared the Bellevillois much more.”9 No matter how much they wanted to defeat the foreigner, they could not bring themselves to do so with the battalions of the working class in the vanguard. For what was not to be the last time in French history, the bourgeoisie chose to capitulate to the Germans, leaving the left as the dominant force within a patriotic front. In 1871, fear of the “enemy within” was to prevail over national pride.

The failure of the French to break the siege of Paris was first interpreted as the product of Prussian superiority and French military ineptitude. But as sortie after sortie promised victory, only to be turned into disaster, honest patriots began to wonder if the powers that be were not playing tricks that bordered on betrayal and treason. The government was increasingly viewed as a ‘‘Government of National Defection”—a phrase Marx was later to use with crushing effect in his passionate defense of the Commune.10 The government was equally reluctant to respond to the Parisian demand for municipal democracy. Since many of the respectable bourgeois had fled, it looked as if elections would deliver municipal power into the hands of the left. Given the suspicions of the monarchists of the right, the Government of National Defense felt it could not afford to concede what had long been demanded. And so it procrastinated endlessly.

As early as October 31, these various threads came together to generate an insurrectionary movement in Paris. Shortly after Bazaine’s ignominious surrender, word got out that the government was negotiating the terms of an armistice with the Prussians. The population of Paris took to the streets and, as the feared Bellevillois descended en masse, took several members of the government prisoner, agreeing to release them only on the verbal assurance that there would be municipal elections and no capitulation. This incident was guaranteed to raise the hackles of the right. It was the immediate cause of the “hateful sentiments towards Paris” that Legentil encountered in December. The government lived to fight another day. But, as events turned out, they were to fight much more effectively against the Bellevillois than they ever fought against the Prussians.

So the siege of Paris dragged on. Worsening conditions in the city now added their uncertain effects to a socially unstable situation.11 The government proved inept and insensitive to the needs of the population, and thereby added fuel to the smoldering fires of discontent. The people lived off cats or dogs, while the more privileged partook of pieces of Pollux, the young elephant from the zoo (forty francs a pound for the trunk). The price of rats—the “taste is a cross between pork and partridge”—rose from sixty centimes to four francs apiece. The government failed to take the elementary precaution of rationing bread until January, when it was much too late. Supplies dwindled, and the adulteration of bread with bone meal became a chronic problem which was made even less palatable by the fact that it was human bones from the catacombs which were being dredged up for the occasion. While the common people were thus consuming their ancestors without knowing it, the luxuries of café life were kept going, supplied by hoarding merchants at exorbitant prices. The rich who stayed behind continued to indulge their pleasures according to their custom, although they paid dearly for it. In callous disregard for the feelings of the less privileged, the government did nothing to curb profiteering or the continuation of conspicuous consumption by the rich.

By the end of December, radical opposition to the Government of National Defense was growing. It led to the publication of the celebrated Affiche Rouge of January 7. Signed by the central committee of the twenty Parisian arrondissements, it accused the government of leading the country to the edge of an abyss by its indecision, inertia, and foot-dragging; suggested that the government knew not how to administer or to fight; and insisted that the perpetuation of such a regime could end only in capitulation to the Prussians. It proclaimed a program for a general requisition of resources, rationing, and mass attack. It closed with the celebrated appeal “Make way for the people! Make way for the Commune!”12 Placarded all over Paris, the appeal had its effect. The military responded decisively and organized one last mass sortie, which was spectacular for its military ineptitude and the carnage left behind. “Everyone understood,” wrote Lissagaray, “that they had been sent out to be sacrificed.”13 The evidence of treason and betrayal was by now overwhelming for those close to the action. It pushed many an honest patriot from the bourgeoisie, who put love of country above class interest, into an alliance with the dissident radicals and the working class.

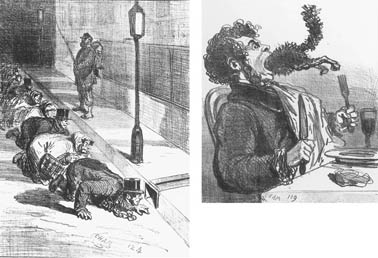

Figure 108 The cartoonist Cham joined with an aging Daumier to try and extract some humor from the desolate months of the 1870 siege of Paris. Here we see Parisians queuing for their nightly share of rat meat; Cham also advises his viewers to take care, when eating mouse, that the cat does not give pursuit.

Figure 109 Thiers had been a frequent subject for Daumier ever since the 1840s. His sudden reappearance on the political stage in 1870 provided another chance for critical comment. In the figure to the left (published on February 24, 1871), Thiers is seen orchestrating the newly elected National Assembly in Bordeaux (but “one can’t see the prompter”), and on the right (published on April 21, after the Commune has been declared) we see Thiers frenetically whipping on his horses, harnessed to the coach of state, in the direction of Versailles. Paris, depicted in the statuesque figure of Liberty, is left with horses straining in the opposite direction, but with head turned disapprovingly towards thiers. The breakup of the state is ominously foretold.

Parisians accepted the inevitable armistice at the end of January with sullen passivity. It provided for national elections to a constituent assembly that would negotiate and ratify a peace agreement. It specified that the French army would lay down its arms, but permitted the National Guard of Paris, which could not easily be disarmed, to remain a fighting force. Supplies came into a starving city under the watchful eyes of the Prussian troops. Most of the remaining bourgeoisie fled to their rural retreats, while the influx of impoverished, unpaid, and demoralized soldiers into the city added to the social and political stresses there. In the February elections, the city returned its quota of radical republicans (Louis Blanc, Hugo, Gambetta, and even Garibaldi). But rural and provincial France voted solidly for peace. Since the left was antagonistic to capitulation, the republicans from the Government of National Defense were seriously compromised by their management of the war, and the Bonapartists were discredited, the peace vote went to the monarchists. Republican Paris was appalled to find itself faced with a monarchist majority in the National Assembly. Thiers, by then seventy-three years old, was elected President in part because of his long experience in politics and in part because the monarchists did not want to be responsible for signing what was bound to be an ignoble peace agreement.

Thiers signed a preliminary peace agreement on February 26 (rather too close to the anniversary of the February Revolution of 1848 for comfort). He ceded Alsace and Lorraine to Germany. Worse still, in Parisians eyes, he agreed to the symbolic occupation of Paris by the Prussian troops on March 1, which could easily have become a bloodbath since many in Paris threatened an armed fight. Only the organizational power of the left (who understood that the Prussians would destroy them, and thus do Thiers’s work for him) and a shadowy new group called the Central Committee of the National Guard prevented a debacle. The Prussians paraded down the Champs Elysée, watched in stony silence by the crowds, with all the major monuments shrouded in black crepe. The humiliation was not easy to forgive, and Thiers was held partly to blame. Thiers also agreed to a huge war indemnity. He was enough of a patriot on this point to resist Bismarck’s suggestion that Prussian bankers float the loan required. Thiers reserved that privilege for the French, and turned this year of troubles into one of the most profitable ones ever for the gentlemen of French high finance.14 The latter informed Thiers that if he was to raise the money, he must first deal with “those rascals in Paris.” This he was uniquely equipped to do. As Minister of the Interior under Louis Philippe, he had, in 1834, been responsible for the savage repression of one of the first genuine working-class movements in French history. Ever contemptuous of “the vile multitude,” he had long had a plan for dealing with them—a plan he had proposed to Louis Philippe in 1848 and which he was now finally in a position to put into effect. He would use the conservatism of the country to smash the radicalism of the city.

On the morning of March 18, the population of Paris awoke to find that the remains of the French army had been sent to Paris to relieve that city of its cannons, obviously a first step toward the disarmament of a populace which had, since September 4, joined the National Guard in massive numbers. The populace of working-class Paris set out spontaneously to reclaim the cannons as their own (had they not, after all, forged them out of metals they had collected during the siege?). On the hill of Montmartre, weary French soldiers stood guard over the powerful battery of cannons assembled there, facing an increasingly restive and angry crowd. General Lecomte ordered his troops to fire. He ordered once, twice, thrice. The soldiers had not the heart to do it, raised their rifle butts in the air, and fraternized joyfully with the crowd. An infuriated mob took General Lecomte prisoner. They stumbled across General Thomas, remembered and hated for his role in the savage killings of the June Days of 1848. The two generals were taken to the garden of no. 6, Rue des Rosiers and, amid considerable confusion and angry argument, put up against a wall and shot.

This incident is of crucial importance. The conservatives now had their martyrs. Thiers could brand the insubordinate population of Paris as murderers and assassins. The hilltop of Montmartre had been a place of martyrdom for Christian saints long before. Conservative Catholics could now add the names of Lecomte and Clément Thomas to that list. In the months and years to come, as the struggle to build the Basilica of Sacré-Coeur unfolded, frequent appeal was to be made to the need to commemorate these ‘‘martyrs of yesterday who died in order to defend and save Christian society.”15 The phrase was actually used in the official legislation passed by the National Assembly in 1873 in support of the building of the basilica. On that sixteenth day of June in 1875 when the foundation stone was laid, Rohault de Fleury rejoiced that the basilica was to be built on a site which, “after having been such a saintly place had become, it would seem, the place chosen by Satan and where was accomplished the first act of that horrible saturnalia which caused so much ruination and which gave the church two such glorious martyrs.” “Yes,” he continued, “it is here where Sacré-Coeur will be raised up that the Commune began, here where generals Clément Thomas and Lecomte were assassinated.” He rejoiced in the “multitude of good Christians who now stood adoring a God who knows only too well how to confound the evil-minded, cast down their designs and to place a cradle where they thought to dig a grave.” He contrasted this multitude of the faithful with a “hillside, lined with intoxicated demons, inhabited by a population apparently hostile to all religious ideas and animated, above all, by a hatred of the Church.”16 GALLIA POENITENS.

Figure 110 The cannons of Montmartre, depicted in this remarkable photo, were mainly created in the Parisian workshops during the siege out of melted-down materials contributed by the populace. They were the flash point of contention that sparked the break between Paris and Versailles.

Thiers’s response to the events of March 18 was to order a complete withdrawal of military and government personnel from Paris. From the safe distance of Versailles, he prepared methodically for the invasion and reduction of Paris. Bismarck proved not at all reluctant to allow the reconstitution of a French army sufficient to the task of putting down the radicals in Paris, and released prisoners and material for that purpose. But, just in case, he kept large numbers of Prussian troops stationed around the city. They were to be silent witnesses to the events that followed.

Left to their own devices, and somewhat surprised by the turn of events, the Parisians, under the leadership of the Central Committee of the National Guard, not only took over all the abandoned administrative apparatus and set it running again with remarkable speed and efficiency (even the theaters reopened), but they also arranged for elections on March 26. The Commune was declared a political fact on March 28.17 It was a day of joyous celebration for the common people of Paris and a day of consternation for the bourgeoisie. But the politics of the Commune were hardly coherent. While a substantial number of workers took their places as elected representatives of the people for the first time in French history, the Commune was still dominated by radical elements from the bourgeoisie. Composed as it was of diverse political currents shading from middle-of-the-road republican through the Jacobins, the Proudhonists, the socialists of the International, and the Blanquist revolutionaries, there was a good deal of factionalism and plenty of contentious argumentation as to what radical or socialist path to take. It was riddled with nostalgia for what might have been, yet in some respects pointed toward a more egalitarian modernist future in which principles of association and of socially organized administration and production could be actively explored. Much of this proved moot, however, since whatever pretensions to modernity the Communards may have had were about to be overwhelmed by a tidal wave of reactionary conservativism. Thiers attacked in early April, and the second siege of Paris began. Rural and provincial France was being put to work to destroy working-class Paris.

What followed was disastrous for the Commune. When the Versailles forces finally broke through the outer defense of Paris—which Thiers had had constructed in the 1840s—they swept quickly through the bourgeois sections of western Paris and cut slowly and ruthlessly down the grand boulevards that Haussmann had constructed into the working-class quarters of the city. Barricades were everywhere, but the military was prepared to deploy cannons to blast them apart and incendiary shells to destroy buildings that housed hostile forces. So began one of the most vicious bloodlettings in an often bloody French history. The Versailles forces gave no quarter. To the deaths in the street fighting—which were not, by most accounts, very extensive—were added an incredible number of arbitrary executions without judgment. Moilin was put to death for his socialist utopian views; a republican deputy and critic of the Commune, Millière, was put to death (after being forced to his knees on the steps of the Pantheon and told to beg forgiveness for his sins—for the first time in his life he cried, “Vive la Commune” instead) because an army captain happened not to like his newspaper articles. The Luxembourg Gardens, the barracks at Lobau, the celebrated and still venerated wall in the cemetery of Père Lachaise, echoed ceaselessly to the sound of gunfire as the executioners went to work. Between twenty and thirty thousand communards died thus. GALLIA POENITENS—with vengeance.

Figure 111 Barricade of the Communards on the Rue d’Allemagne, March 1871.

Figure 112 Some three hundred of the last Communards captured at the end of the “bloody week” of May 1871 were arbitrarily shot at the Mur des Fedérés in Père Lachaise cemetery, turning the wall into a place of pilgrimage for decades to come. Gouache by Alfred Darjon.

Figure 113 Communards shot by the Versailles forces (photo attributed to Disdéri). Someone has placed a white wreath in the hands of the young woman at the bottom right (a symbol of Liberty, once again about to be interred?).

Out of this sad history there is one incident that commands our attention. On the morning of May 28, an exhausted Eugène Varlin—bookbinder; union and food cooperative organizer under the Second Empire; member of the National Guard; intelligent, respected, and scrupulously honest, committed socialist; member of the Commune and brave soldier—was recognized and arrested. He was taken to that same house on Rue des Rosiers where Lecomte and Clément Thomas died. Varlin’s fate was worse. Sentenced to die, he was paraded around the hillside of Montmartre, some say for ten minutes and others for hours, abused, beaten, and humiliated by a fickle mob. He was finally propped up against a wall (his face already smashed in and one eye out of its socket) and shot. He was just thirty-two years old. They had to shoot twice to kill him. In between fusillades he cried, evidently unrepentant, “Vive la Commune!” His biographer called it “the Calvary of Eugène Varlin.” The left can have its martyrs, too. And it is on that spot that Sacré-Coeur is built.18

Figure 114 The toppling of the Vendôme Column, here depicted by Meaulle and Viers, created a lot of interest, illustrating how buildings and monuments were deeply political symbols to Parisians.

The “bloody week,” as it was called, also involved an enormous destruction of property. The Communards, to be sure, were not enamored of the privileges of private property and were not averse to destroying hated symbols. The Vendôme Column—which Napoleon III had doted upon—was toppled in a grand ceremony on the May 16 to symbolize the end of authoritarian rule. The painter Courbet was later held responsible for this act, and condemned to pay for the reconstruction of the monument out of his own pocket. The Communards also decreed, but never carried out, the destruction of the Chapel of Expiation, by which Louis XVIII had sought to impress upon Parisians their guilt in executing his brother. And when Thiers had shown his true colors, the Communards took a certain delight in dismantling his Parisian residence, stone by stone, in a symbolic gesture that Goncourt felt had an “excellent bad effect.” But the wholesale burning of Paris was another matter entirely. To the buildings set afire in the course of the bombardment were added those deliberately fired for strategic reasons by the retreating Communards. From this arose the myth of the “incendiaries” of the Commune who recklessly took revenge, it was said, by burning everything they could. The false myth of the hideous woman petroleuse was circulated by the Versailles press, and women under suspicion were arbitrarily shot on the spot. A bourgeois diarist, Audéoud, complacently recorded how he denounced a well-dressed woman in the Rue Blanche as a petroleuse because she was carrying two bottles (filled with what we will never know). When she pushed a lunging and rather drunken soldier away, the soldier shot her in the back.19

No matter what the truth of the matter, the myth of the incendiaries was strong. Within a year, the Pope describing the Communards as “devils risen up from hell bringing the fires of the inferno to the streets of Paris.” The ashes of the city became a symbol of the Commune’s crimes against the church and were to fertilize the soil from which the energy to build Sacré-Coeur was to spring. No wonder that Hubert Rohault de Fleury congratulated himself upon that felicitous choice of words—“were Paris to be reduced to cinders.” That phrase could strike home with redoubled force, he noted, “as the incendiaries of the Commune came to terrorize the world.”20

The aftermath of the Commune was anything but pleasant. Bodies littered the streets and the stench became unbearable. To take just one example, the three hundred or so bodies unceremoniously dumped into the lake in Haussmann’s beautiful new park at Buttes Chaumont (once a site for hanging petty criminals and later a municipal dump) had to be dragged out after they surfaced, horribly bloated, several days later; they were burned in a funeral pyre that lasted for days. Audéoud delighted in the sight of all the bodies “riddled with bullets, befouled and rotting,” and took “the stink of their corpses” as “an odor of peace, and if the all-too sensitive nostril revolts, the soul rejoices.” “We, too,” he went on, “have become cruel and pitiless and we should find it a pleasure to bathe and wash our hands in their blood.” But the bloodletting began to turn the stomachs of many within the bourgeoisie until all but the most sadistic of them had to cry “Stop!” The celebrated diarist Edmond de Goncourt tried to convince himself of the justice of it all when he wrote: “It is good that there was neither conciliation nor bargain. The solution was brutal. It was by pure force. The solution has held people back from cowardly compromises … the bloodletting was a bleeding white; such a purge, by killing off the combative part of the population defers the next revolution by a whole generation. The old society has twenty years of quiet ahead of it, if the powers that be dare all that they may dare at this time.”21 These sentiments were exactly those of Thiers. But when de Goncourt later passed through Belleville and saw the “faces of ugly silence,” he could not help but feel that here was a “vanquished but unsubjugated district.” Was there no other way to purge the threat of revolution?

The experience of 1870–1871, taken together with the confrontation between Napoleon III and the decadent “festive materialism” of the Second Empire, plunged Catholics into a phase of widespread soul-searching. The majority of them accepted the notion that France had sinned, and this gave rise to manifestations of expiation and a movement of piety that was both mystical and spectacular. The intransigent and ultramontane Catholics unquestionably favored a return to law and order and a political solution founded on respect for authority. And it was the monarchists, generally themselves intransigent Catholics, who held out the promise for law and order. Liberal Catholics found all of this disturbing, but they were in no position to mobilize their forces since even the Pope dismissed them as the “veritable scourge” of France. There was little to stop the consolidation of the bond between monarchism and intransigent Catholicism. And it was this powerful alliance that was to guarantee the building of Sacré-Coeur.

The immediate problem for the progenitors of the vow was, however, to operationalize a pious wish. This required official action. Legentil and Rohault de Fleury sought the support of the newly appointed Archbishop of Paris. Monseigneur Guibert, a compatriot of Thiers from Tours, had required some persuading to take the position in Paris. The three previous archbishops had suffered violent deaths: the first during the insurrection of 1848, the second by the hand of an assassin in 1863, and the third during the Commune. The Communards had early decided to take hostages in response to the butchery promised by Versailles. The Archbishop was held as a prime hostage for whom the Communards sought the exchange of Blanqui. Thiers refused that negotiation, apparently having decided that a dead and martyred Archbishop (who was a liberal Catholic in any case) was more valuable to him than a live one exchanged for a dynamic and aggressive Blanqui. During “the bloody week,” certain segments among the Communards took whatever vengeance they could. On May 24, with the Versaille forces hacking their way into Paris in the bloodiest and most brutal fashion, executing anyone they suspected of having played an active role in the Commune, the Archbishop was shot. In that final week, seventy-four hostages were shot, of whom twenty-four were priests. That awesome anticlericalism was as alive under the Commune as it had been in 1789. But with the massive purge that left more than twenty thousand Communards dead, nearly forty thousand imprisoned, and countless others in flight, Thiers could write reassuringly on June 14 to Monsignor Guibert: “The ‘reds,’ totally vanquished, will not recommence their activities tomorrow; one does not engage twice in fifty years in such an immense fight as they have just lost.”32 Reassured, Monsignor Guibert came to Paris.

Figure 115 This view, from the hilltop of Montmartre, of Paris burning in the final days of the Commune captures something of what Rohault de Fleury had in mind when he commented on how fortuitously appropriate it had been to make the vow to build Sacré-Coeur even if “Paris were reduced to ashes.”

Figure 116 Remorse and revulsion for what happened in the Commune were initially confined to republicans of a social democratic persuasion. Manet (top) was deeply moved by the events, and drew several representations mourning the deaths on the barricades. Daumier (bottom), in one of his last drawings, commented sadly and poignantly on “when workers fight each other.”

The new Archbishop was much impressed with the movement to build a monument to the Sacred Heart. On January 18, 1872, he formally accepted responsibility for the undertaking. He wrote to Legentil and Rohault de Fleury thus:

You have considered from their true perspective the ills of our country. … The conspiracy against God and Christ has prevailed in a multitude of hearts and in punishment for an almost universal apostasy, society has been subjected to all the horrors of war with a victorious foreigner and an even more horrible war amongst the children of the same country. Having become, by our prevarication, rebels against heaven, we have fallen during our troubles into the abyss of anarchy. The land of France presents the terrifying image of a place where no order prevails, while the future offers still more terrors to come. … This temple, erected as a public act of contrition and reparation … will stand amongst us as a protest against other monuments and works of art erected for the glorification of vice and impiety.23

By July 1872, the ultraconservative Pope Pius IX, still awaiting his deliverance from captivity in the Vatican, formally endorsed the vow. An immense propaganda campaign unfolded, and the movement gathered momentum. By the end of the year, more than a million francs were promised, and all that remained was to translate the vow into its material, physical representation.

The first step was to choose a site. Legentil wanted to use the foundations of the still-to-be-completed Opera House, which he considered “a scandalous monument of extravagance, indecency and bad taste.”24 The initial restrained design of that building by Charles Rohault de Fleury (no relation of Hubert) had, in 1860, been dropped at the insistence of Count Walewski (“who had the dubious distinction of being the illegitimate son of Napoleon and the husband of Napoleon III’s current favorite”25). The design that replaced it, by Garnier (which exists today), most definitely qualified in the eyes of Legentil as a “monument to vice and impiety,” and nothing could be more appropriate than to efface the memory of Empire by constructing the basilica on that spot. This would have meant, of course, tearing down the façade that had been completed in 1867. It probably escaped Legentil’s attention that the Communards had, in the same spirit, toppled the Vendôme Column.

By late October 1872, however, the Archbishop had taken matters into his own hands and selected the heights of Montmartre because it was only from there that the symbolic domination of Paris could be assured. Since the land on that site was in part public property, the consent or active support of the government was necessary if it was to be acquired. The government was considering the construction of a military fortress on that spot. The Archbishop pointed out, however, that a military fortress could well be very unpopular, while a fortification of the sort he was proposing might be less offensive and more sure. Thiers and his ministers, apparently persuaded that ideological protection might be preferable to military, encouraged the Archbishop to pursue the matter formally. This the latter did in a letter of March 5, 1873. He requested that the government pass a special law declaring the construction of the basilica a work of public utility. This would permit the laws of expropriation to be used to procure the site.

Such a law ran counter to a long-standing sentiment in favor of the separation of church and state. Yet conservative Catholic sentiment for the project was very strong. Thiers procrastinated, but his indecision was shortly rendered moot. The monarchists had decided that their time had come. On May 24, 1873, they drove Thiers from power and replaced him with the archconservative royalist Marshal MacMahon, who just two years before, had led the armed forces of Versailles in the bloody repression of the Commune. France was plunged, once more, into political ferment; a monarchist restoration seemed imminent.

The MacMahon government quickly reported out the law, which then became part of its program to establish the rule of moral order in which those of wealth and privilege—who therefore had an active stake in the preservation of society—would, under the leadership of the king and in alliance with the authority of the church, have both the right and the duty to protect France from the social perils to which it had recently been exposed, thereby preventing the country from falling into the abyss of anarchy. Large-scale demonstrations were mobilized by the church as part of a campaign to reestablish some sense of moral order. The largest of these demonstrations took place on June 29, 1873, at Paray-le-Monial. Thirty thousand pilgrims, including fifty members of the National Assembly, journeyed there to dedicate themselves publicly to the Sacred Heart.26

It was in this atmosphere that the committee formed to report on the law presented its findings on July 11 to the National Assembly; a quarter of the committee members were adherents to the vow. The committee found that the proposal to build a basilica of expiation was unquestionably a work of public utility. It was right and proper to build such a monument on the heights of Montmartre for all to see, because it was there that the blood of martyrs—including those of yesterday—had flowed. It was necessary “to efface by this work of expiation, the crimes which have crowned our sorrows,” and France, “which has suffered so much,” must “call upon the protection and grace of Him who gives according to His will, defeat or victory.”27

The debate that followed on July 22 and 23 in part revolved around technical-legal questions and the implications of the legislation for state-church relations. The intransigent Catholics recklessly proposed to go much further. They wanted the Assembly to commit itself formally to a national undertaking that “was not solely a protestation against taking up of arms by the Commune, but a sign of appeasement and concord.” That amendment was rejected, but the law passed with a handsome majority of 244 votes. A lone dissenting voice in the debate came from a radical republican deputy from Paris:

When you think to establish on the commanding heights of Paris—the fount of free thought and revolution—a Catholic monument, what is in your thoughts? To make of it the triumph of the Church over revolution. Yes, that is what you want to extinguish—what you call the pestilence of revolution. What you want to revive is the Catholic faith, for you are at war with the spirit of modern times. … Well, I who know the sentiments of the population of Paris, I who am tainted by the revolutionary pestilence like them, I tell you that the population will be more scandalized than edified by the ostentation of your faith. … Far from edifying us, you push us towards free thought, towards revolution. When people see these manifestations of the partisans of monarchy, of the enemies of the Revolution, they will say to themselves that Catholicism and monarchy are unified, and in rejecting one they will reject the other.28

Armed with a law that yielded powers of expropriation, the committee formed to push the project through to fruition acquired the site atop Butte Montmartre. They collected the moneys promised and set about soliciting more so that the building could be as grand as the thought that lay behind it. A competition for the design of the basilica was set and judged. The building had to be imposing, consistent with Christian tradition, yet quite distinct from the “monuments to vice and impiety” built in the course of the Second Empire. Out of the seventy-eight designs submitted and exhibited to the public, that of the architect Abadie was selected. The choice was controversial. Accusations of too much insider influence quickly surfaced, and conservative Catholics were distressed at what they saw as the “orientalism” of the design. Why could it not be more authentically French, they asked (which at that time meant true to the Gothic traditions of the thirteenth century, even as rationalized by Viollet-le-Duc)? But the grandeur of Abadie’s domes, the purity of the white marble, and the unadorned simplicity of its detail impressed the committee—what, after all, could be more different from the flamboyance of that awful Opera House?29

By the spring of 1875, all was ready for putting the first stone in place. But radical and republican Paris, apparently, was not yet repentant enough. The Archbishop complained that the building of Sacré-Coeur was being treated as a provocative act, as an attempt to inter the principles of 1789. And while, he said, he would not pray to revive those principles if they happened to become dead and buried, this view of things was giving rise to a deplorable polemic in which the Archbishop found himself forced to participate. He issued a circular in which he expressed his astonishment at the hostility expressed toward the project on the part of “the enemies of religion.” He found it intolerable that people dared to put a political interpretation upon thoughts derived only out of faith and piety. Politics, he assured his readers, “had been far, far from our inspirations; the work had been inspired, on the contrary, by a profound conviction that politics was powerless to deal with the ills of the country. The causes of these ills are moral and religious and the remedies must be of the same order.” Besides, he went on, the work could not be construed as political because the aim of politics is to divide, “while our work has for its goal the union of all. Social pacification is the end point of the work we are seeking to realize.”30

The government, now clearly on the defensive, grew extremely nervous at the prospect of a grand opening ceremony that could be the occasion for an ugly confrontation. It counseled caution. The committee had to find a way to lay the first stone without being too provocative. The Pope came to their aid and declared a day of dedication to the Sacred Heart for all Catholics everywhere. Behind that shelter, a much scaled-down ceremony to lay the first stone passed without incident. The construction was now underway. GALLIA POENITENS was taking shape in material, symbolic form.

The forty years between the laying of the foundation stone and the final consecration of the basilica in 1919 were often troubled ones. Technical difficulties arose in the course of putting such a large structure on a hilltop rendered unstable by years of mining for gypsum. The cost of the structure increased dramatically, and as enthusiasm for the cult of the Sacred Heart diminished somewhat, financial difficulties ensued. Abadie died in 1884, and his successors both added to and subtracted from his original design (the most notable addition was a very considerable increase in the height of the central dome). And the political controversy continued. The committee in charge of the project had early decided upon a variety of stratagems to encourage the flow of contributions. Individuals and families could purchase a stone, and the visitor to Sacré-Coeur will see the names of many such inscribed upon the stones there. Different regions and organizations were encouraged to subscribe toward the construction of particular chapels. Members of the National Assembly, the army, the clergy, and the like all pooled their efforts in this way. Each particular chapel has its own significance.

Among the chapels in the crypt, for example, is that of Jésus-Enseignant, which recalls, as Rohault de Fleury put it, “that one of the chief sins of France was the foolish invention of schooling without God.”31 Those who were on the losing side of the fierce battle to preserve the power of the church over education after 1871 put their money here. And next to that chapel, at the far end of the crypt, close to the line where the Rue des Rosiers used to run, stands the Chapel to Jésus-Ouvrier. That Catholic workers sought to contribute to the building of their own chapel was a matter for great rejoicing. It showed, wrote Legentil, the desire of workers “to protest against the fearsome impiety into which a large part of the working class is falling,” as well as their determination to resist “the impious and truly infernal association which, in nearly all of Europe, makes of it its slave and victim.” The reference to the International Working Men’s Association is unmistakable and understandable, since it was customary in bourgeois circles at that time to attribute the Commune, quite erroneously, to the nefarious influence of that ‘infernal” association. Yet, by a strange quirk of fate, which so often gives an ironic twist to history, the chapel to Jésus-Ouvrier stands almost exactly at the spot where ran the course of the “Calvary of Eugène Varlin.” Thus it is that the basilica, erected on high in part to commemorate the blood of two recent martyrs of the right, unwittingly commemorates in its subterranean depths a martyr of the left.

Legentil’s interpretation of all this was in fact somewhat awry. In the closing stages of the Commune, a young Catholic named Albert de Munn watched in dismay as the Communards were led away to slaughter. Shocked, he fell to wondering what “legally constituted society had done for these people,” and concluded that their ills had in large measure been visited upon them through the indifference of the affluent classes. In the spring of 1872, he went into the heart of hated Belleville and set up the first of his cerclesouvriers.32 This signaled the beginnings of a new kind of Catholicism in France—one that sought through social action to attend to the material as well as the spiritual needs of the workers. It was through organizations such as this, a far cry from the intransigent, ultramontane Catholicism that ruled at the center of the movement for the Sacred Heart, that a small trickle of worker contributions began to flow toward the construction of a basilica on the hilltop of Montmartre.

The political difficulties mounted, however. France, finally armed with a republican constitution (largely because of the intransigence of the monarchists) was now in the grip of a modernization process fostered by easier communications, mass education, and industrial development. The country moved to accept the moderate form of republicanism and became bitterly disillusioned with the backward-looking monarchism that had dominated the National Assembly elected in 1871. In Paris the “unsubjugated” Bellevillois, and their neighbors in Montmartre and La Villette, began to reassert themselves rather more rapidly than Thiers had anticipated. As the demand for amnesty for the exiled Communards became stronger in these quarters, so did the hatred of the basilica rising in their midst. The agitation against the project mounted.

On August 3, 1880, the matter came before the city council in the form of a proposal—a “colossal statue of Liberty will be placed on the summit of Montmartre, in front of the church of Sacré-Coeur, on land belonging to the city of Paris.” The French republicans at that time had adopted the United States as a model society, which functioned perfectly well without monarchism and other feudal trappings. As part of a campaign to drive home the point of this example, as well as to symbolize their own deep attachment to the principles of liberty, republicanism, and democracy, they were then raising funds to donate the Statue of Liberty that now stands in New York Harbor. Why not, said the authors of this proposition, efface the sight of the hated Sacré-Coeur by a monument of similar order?33

No matter what the claims to the contrary, they said, the basilica symbolized the intolerance and fanaticism of the right—it was an insult to civilization, antagonistic to the principles of modern times, an evocation of the past, and a stigma upon France as a whole. Parisians, seemingly bent on demonstrating their unrepentant attachment to the principles of 1789, were determined to efface what they felt was an expression of “Catholic fanaticism” by building exactly that kind of monument that the Archbishop had previously characterized as a “glorification of vice and impiety.” By October 7 the city council had changed its tactics. Calling the basilica “an incessant provocation to civil war,” the members decided by a vote of 61 to 3 to request the government to “rescind the law of public utility of 1873” and to use the land, which would revert to public ownership, for the construction of a work of truly national significance. Neatly sidestepping the problem of how those who had contributed to the construction of the basilica—which had hardly yet risen above its foundations—were to be indemnified, it passed along its proposal to the government. By the summer of 1882, the request was taken up in the Chamber of Deputies.

Archbishop Guibert had, once more, to take up the public defense of the work. He challenged what by now were familiar arguments against the basilica with familiar responses. He insisted that the work was not inspired by politics but by Christian and patriotic sentiments. To those who objected to the expiatory character of the work, he simply replied that no one can ever afford to regard their country as infallible. As to the appropriateness of the cult of the Sacred Heart, he felt only those within the church had the right to judge. To those who portrayed the basilica as a provocation to civil war, he replied: “Are civil wars and riots ever the product of our Christian temples? Are those who frequent our churches ever prone to excitations and revolts against the law? Do we find such people in the midst of disorders and violence which, from time to time, trouble the streets of our cities?” He went on to point out that while Napoleon had sought to build a temple of peace at Montmartre, “it is we who are building, at last, the true temple of peace.”34 He then considered the negative effects of stopping the construction. Such an action would profoundly wound Christian sentiment and prove divisive. It would surely be a bad precedent, he said (blithely ignoring the precedent set by the law of 1873 itself), if religious undertakings of this sort were to be subject to the political whims of the government of the day. And then there was the complex problem of compensation, not only for the contributors but also for the work already done. Finally, he appealed to the fact that the work was giving employment to six hundred families—to deprive “that part of Paris of such a major source of employment would be inhuman indeed.”

Figure 117 The Statue of Liberty in its Paris workshop before being shipped to New York.

The Parisian representatives in the Chamber of Deputies, which by 1882 was dominated by reformist republicans such as Gambetta (from Belleville) and Clemenceau (from Montmartre), were not impressed by these arguments. The debate was heated and passionate. The government declared itself unalterably opposed to the law of 1873 but was equally opposed to rescinding the law, since this would entail paying out more than twelve million francs in indemnities to the church. In an effort to defuse the evident anger from the left, the minister went on to remark that by rescinding the law, the Archbishop would be relieved of the obligation to complete what was proving to be a most arduous undertaking and the church would be provided with millions of francs to pursue works of propaganda that might be “infinitely more efficacious than that to which the sponsors of the present motion are objecting.”

The radical republicans were not about to regard Sacré-Coeur in the shape of a white elephant, however. Nor were they inclined to pay compensation. They were determined to do away with what they felt was an odious manifestation of pious clericalism and to put in its place a monument to liberty of thought. They put the blame for the civil war squarely on the shoulders of the monarchists and their intransigent Catholic allies. Clemenceau rose to state the radical case. He declared the law of 1873 an insult, an act of a National Assembly that had sought to impose the cult of the Sacred Heart on France because “we fought and still continue to fight for human rights, for having made the French Revolution.” The law was the product of clerical reaction, “an attempt to stigmatize revolutionary France, to condemn us to ask pardon of the Church for our ceaseless struggle to prevail over it in order to establish the principles of liberty, equality and fraternity. We must,” he declared, “respond to a political act by a political act.” Not to do so would be to leave France under the intolerable invocation of the Sacred Heart.35

With impassioned oratory such as this, Clemenceau fanned the flames of anticlerical sentiment. The Chamber of Deputies voted to rescind the law of 1873 by 261 votes to 199. It appeared that the basilica, the walls of which had hardly risen above their foundations, was to come tumbling down. But it was saved by a technicality. The law was passed too late in the session to meet all the formal requirements for promulgation. The government, genuinely fearful of the costs and liabilities involved, quietly worked to prevent the reintroduction of the motion into a Chamber of Deputies that, in the next session, moved on to consider matters of much greater weight and moment. The Parisian republicans had gained a symbolic but Pyrrhic parliamentary victory. A relieved Archbishop pressed on with the work.

Yet somehow the matter would not die. In February 1897, the motion was reintroduced. Anticlerical republicanism had by then made great progress, as had the working-class movement in the form of a vigorous and growing socialist party. But the construction atop the hill had likewise progressed. The interior of the basilica had been inaugurated and opened for worship in 1891, and the great dome was well on the way to completion (the cross that surmounts it was formally blessed in 1899). Although the basilica was still viewed as a “provocation to civil war,” the prospect for dismantling such a vast work was by now quite daunting. And this time it was none other than Albert de Munn who defended the basilica in the name of a Catholicism that had, by then, seen the virtue of separating its fate from that of a fading monarchist cause. The church was beginning to learn a lesson, and the cult of the Sacred Heart began to acquire a new meaning in response to a changing social situation. By 1899, a more reform-minded Pope dedicated the cult to the ideal of harmony among the races, social justice, and conciliation.36

But the socialist deputies were not impressed by what they saw as maneuvers of co-optation. They pressed home their case to bring down the hated symbol, even though almost complete, and even though such an act would entail indemnifying eight million subscribers to the tune of thirty million francs. But the majority in the Chamber of Deputies blanched at such a prospect. The motion was rejected by 322 to 196. This was to be the last time the building was threatened by official action. With the dome completed in 1899, attention switched to the building of the campanile, which was finally finished in 1912. By the spring of 1914, all was ready and the official consecration set for October 17. But war with Germany intervened. Only at the end of that bloody conflict was the basilica finally consecrated. A victorious France—led by the fiery oratory of Clemenceau—joyfully celebrated the consecration of a monument conceived of in the course of a losing war with Germany a generation before. GALLIA POENITENS at last brought its rewards.

Muted echoes of this tortured history can still be heard. In February 1971, for example, demonstrators pursued by police took refuge in the basilica. Firmly entrenched there, they called upon their radical comrades to join them in occupying a church “built upon the bodies of Communards in order to efface the memory of that red flag that had for too long floated over Paris.” The myth of the incendiaries immediately broke loose from its ancient moorings, and an evidently panicked rector summoned the police to the basilica to prevent the conflagration. The “reds” were chased from the church amid scenes of great brutality. In commemoration of those who lost their lives in the Commune, an action artist, Pignon-Ernest, covered the steps below the basilica with shrouds bearing images of the Communard dead in the month of May. Thus was the centennial of the Paris Commune celebrated on that spot. And as a coda to that incident, a bomb exploded in the basilica in 1976, causing quite extensive damage to one of the domes. On that day, it was said, the visitor to the cemetery of Père Lachaise would have seen a single red rose on August Blanqui’s grave.

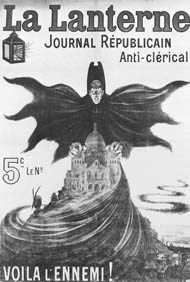

Figure 118 Sacré-Coeur as vampire, an Affiche for La lanterne, a journal, around 1896.

Rohault de Fleury had desperately wanted to “place a cradle where [others] had thought to dig a grave.” But the visitor who looks at the mausoleum-like structure that is Sacré-Coeur might well wonder what is interred there. The spirit of 1789? The sins of France? The alliance between intransigent Catholicism and reactionary monarchism? The blood of martyrs like Lecomte and Clément Thomas? Or that of Eugène Varlin and the twenty thousand or so Communards mercilessly slaughtered along with him?

The building hides its secrets in sepulchral silence. Only the living, cognizant of this history, who understand the principles of those who struggled for and against the embellishment of that spot, can truly disinter the mysteries that lie entombed there, and thereby rescue that rich experience from the deathly silence of the tomb and transform it into the noisy beginnings of the cradle.