The world is a severe schoolmaster.

—Phillis Wheatley, the first published African-American poet (1753?–1784)

THE NEWS that a schoolgirl had been arrested for refusing to surrender her bus seat to a white passenger flashed through Montgomery’s black community and traveled far beyond. One man from Sacramento, California, wrote to Claudette:

The wonderful thing which you have just done makes me feel like a craven coward. How encouraging it would be if more adults had your courage, self-respect and integrity.

In Montgomery, students stopped one another at bus corners and by their lockers, saying things like “Have you ever heard of Claudette Colvin?” “Well, do you know anyone who knows her?” “Where’s she go to school?”

Jo Ann Robinson, a professor of English at Alabama State College at the time, later wrote, “[With]in a few hours, every Negro youngster on the streets discussed Colvin’s arrest. Telephones rang. Clubs called special meetings and discussed the event with some degree of alarm. Mothers expressed concern about permitting their children on the buses.”

Jo Ann Robinson had a personal reason to admire anyone who took on the bus system. In 1949, just after she had moved to Montgomery, Robinson had boarded a bus for the airport. It was Christmas break, and she was flying off to Cleveland to visit relatives. After dropping a dime in the fare box, she absentmindedly sat down in one of the ten front seats reserved for whites. Still new to town, she hadn’t thought to walk to the back. Besides, there were only two other passengers on the entire bus. Lost in holiday thoughts, she was startled by the realization that someone’s face was inches from hers. It was the bus driver, shouting, “Get up from there! Get up from there!” His hand was drawn back as if to strike her. She snatched up her packages and stumbled out the front door, nearly sprawling in the mud as the bus pulled away. “I felt like a dog,” she later wrote.

He had picked the wrong person to bully. Smart, energetic, and extremely well-connected, Jo Ann Robinson was an active member of the Women’s Political Council, a large and influential civic group of professional black women in Montgomery. Some WPC members were Alabama State College professors; others, including Claudette’s teacher, Geraldine Nesbitt, were ASC graduates who had become teachers. Shortly after Robinson took over as president of the WPC in 1950, she led a successful campaign to make white merchants include the titles “Mr.,” “Mrs.,” and “Miss” on bills and announcements sent to black customers. It was an important measure of respect.

Jo Ann Robinson, professor of English at Alabama State College and leader of Montgomery’s influential Women’s Political Council

Though Robinson owned her own car and rarely rode the city bus, the memory of the driver’s bullying behavior and how humiliated she had felt wouldn’t go away. She started interviewing black residents who had been mistreated on the city buses and writing down their stories. She soon possessed a thick file of nightmare accounts.

Robinson longed to do something about the buses, but she didn’t know quite what. In March 1954, she organized a face-to-face meeting of black leaders, city officials, and bus company representatives to complain about the way blacks were treated on the buses and to propose reforms. The meeting was pleasant enough but unproductive.

She kept at it. Two months later she wrote a letter to Montgomery’s mayor, W. A. “Tacky” Gayle, on behalf of the Women’s Political Council. Robinson pressed for three changes to the bus rules:

1. A new seating plan that would let blacks sit from back to front and whites from front to back until the bus filled up, as was the practice in several other Southern cities.

2. An end to making blacks pay their fares at the front of the bus but then get off and reenter through the rear door to find a seat at the back.

3. A requirement that drivers stop at every corner in black neighborhoods just as they did in white neighborhoods.

Robinson’s diplomatic letter contained one fragment of steel. In the third to last paragraph she wrote that, if things did not get better, “there has been talk from twenty-five or more local organizations of planning a city-wide boycott of busses.”

The idea of a bus boycott had been gaining momentum throughout the black community for months. Its power was obvious: three-quarters of Montgomery’s bus passengers were black. If everyone quit riding, they could starve the City Lines bus company into reason. Still, the letter stopped short of calling for an end to segregated seating. As Robinson later wrote, “In Montgomery in 1955 no one was brazen enough to announce publicly that black people might boycott City buses for the specific purpose of integrating those buses. Just to say that minorities wanted ‘better seating arrangements’ was bad enough.”

BUS BOYCOTTS

The idea of boycotting—or staying off—public vehicles until reforms were made was nothing new, but it had never succeeded for long on a large scale. Between 1900 and 1906, Montgomery was one of twenty-five Southern cities to protest segregated streetcars through boycotts. More recently, in June 1953, the black community of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, had boycotted the city’s buses for several days to protest segregated seating. Though they weren’t able to evict Jim Crow, the Baton Rouge protesters developed a free-ride transportation system and left a detailed blueprint for other bus protesters to follow.

Robinson’s letter led only to more polite meetings. The whites offered coffee, nodded, and smiled, but refused to budge an inch when it came to Jim Crow. Still, Claudette Colvin’s arrest had stripped the veneer of politeness from the talks. She had been wrenched from her seat and dragged off a bus by police in front of shocked witnesses. People were angry.

Claudette’s arrest made her the center of attention wherever she went. On the following Sunday, Reverend Johnson led the congregation in prayer for the girl among them who had been arrested for bravely standing up to the bus driver and the police and challenging the whole ugly system. The next day classmates swarmed around her when she pulled up to Booker T. Washington High School in her cousin’s car. They followed her into homeroom and asked to hear her story. Students pointed at her in the halls, whispering, “There’s the girl who got arrested.”

Opinion at Booker T. Washington was sharply divided between those who admired Claudette’s courage and those who thought she got what she deserved for making things harder for everyone. Some said it was about time someone stood up. Others told her that if she didn’t like the way things were in the South, she should go up North. Still others couldn’t make up their minds: no one they knew had ever done anything like this before.

“A few of the teachers like Miss Nesbitt embraced me,” Claudette recalls. “They kept saying, ‘You were so brave.’ But other teachers seemed uncomfortable. Some parents seemed uncomfortable, too. I think they knew they should have done what I did long before. They were embarrassed that it took a teenager to do it.”

Facing serious criminal charges, and with her court hearing only two weeks away, Claudette feared she might be sent to a reform school as a juvenile delinquent. She had a lot to lose: she was a good student with dreams of college and a career. She was not about to plead guilty to anything, but she didn’t know what to do or whom to turn to. Somehow, she had to find a lawyer, and figure out how to pay for one. She had no time to lose.

CLAUDETTE: Everybody got busy. We started working family connections, trying to find someone to help me. My great-aunt’s husband, C. J. McNear, told my parents to get in touch with Mr. E. D. Nixon. C.J. thought my case might be a good civil rights case. Mr. Nixon called the shots in the black community of Montgomery. He knew everybody. So Mom called him. And he agreed to help us.

NIXON MOVED SWIFTLY on two fronts. He called Fred Gray, one of Montgomery’s two black lawyers, and convinced him to represent Claudette in court. Then he organized a committee of black leaders to meet downtown with the police commissioner. Among those selected was the new pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, twenty-six-year-old Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The attempt to obtain justice for Claudette Colvin marked Dr. King’s political debut.

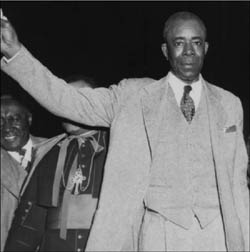

E. D. NIXON

When black people had serious problems in Montgomery, they went to E. D. Nixon. Employed as a railroad sleeping car porter, Nixon worked tirelessly throughout his life to advance the rights of black people. A tall, rugged man with a commanding voice and an earthy sense of humor, Nixon seemed to know everyone: jailers, white policemen, judges, newspaper reporters, lawyers, and government officials. An early president of the Montgomery Chapter of the NAACP, Nixon was often able to fix common people’s problems through plain talk and informal dealing before they hardened into legal cases.

A conference of black leaders, the bus company’s manager, and the police commissioner seemed to break the tension. “Both men were quite pleasant, and expressed deep concern over what had happened [to Claudette],” Dr. King later wrote. The bus company conceded that, according to the driver, Claudette had been sitting behind the ten white seats in front and there had been no seats available when the driver ordered her to move. That seemed to be an admission that she hadn’t broken the law. The police commissioner agreed the seating rules were confusing and promised that the city’s attorney would soon clarify them in writing. The one thing they didn’t do was drop the charges against Claudette. The trial would go on.

Still, Dr. King walked out of the meeting feeling “hopeful,” and Jo Ann Robinson also felt her spirits lifting as she stepped outside. “[We] were given to understand . . . that . . . Claudette would be given every chance to clear her name,” she later wrote. “It was not [to be] a trial to determine guilt or innocence, but an effort to find out the truth, and if the girl were found innocent, her record would be clear . . . Those present left the conference feeling . . . that everything would work out fairly for everyone.”

Plainspoken E. D. Nixon, longtime leader of the Montgomery NAACP

In the days before Claudette’s trial, E. D. Nixon also called Rosa Parks, a soft-spoken, forty-two-year-old professional seamstress who had for many years been secretary of the Montgomery NAACP. Mrs. Parks was also the head of the NAACP’s youth group in Montgomery. Nixon and Mrs. Parks had long tried to get more young blacks involved in the struggle for civil rights, but the Sunday afternoon NAACP youth meetings were, for the most part, poorly attended. However, both saw promise in the dramatic arrest, jailing, and trial of a fifteen-year-old bus protester. It might spark interest if the girl was willing to tell her story. Nixon urged Mrs. Parks to get Claudette Colvin involved with the NAACP.

CLAUDETTE: The first time I ever met Rosa Parks was one Sunday afternoon when she walked into a church before an NAACP youth meeting. There were only a few students around. This small, fair-skinned woman with long, straight hair came up to me, and looked me up and down. She said, “You’re Claudette Colvin? Oh my God, I was lookin’ for some big old burly overgrown teenager who sassed white people out . . . But no, they pulled a little girl off the bus.” I said, “They pulled me off because I refused to walk off.”

Rosa had already asked the teachers at my school about me and found out I was a good student. She got even more interested when she realized she knew my mother—my biological mom—from Pine Level. Rosa had lived there, too, when she was younger. Mom was close friends with Rosa’s brother, Sylvester, before she left Pine Level for Birmingham.

Rosa Parks worked as a department store seamstress and served for many years as the secretary of Montgomery’s branch of the NAACP. Pleasant and soft-spoken, she was a steely foe of racial segregation

We did all sorts of things to raise money for my lawyer. Rosa’s mother baked and sold cookies. I was always eating them, and Rosa would come up and say, “Claudette, don’t eat all the cookies or we won’t have any to sell.” Rosa put me up for Miss NAACP, Montgomery Chapter. I finished second, but it didn’t matter; all the money from the contest went to pay my lawyer anyway.

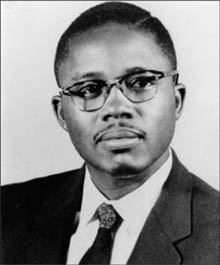

CLAUDETTE’S LAWYER wasn’t much older than she was. Bespectacled, serious, sporting a pencil-thin mustache, and usually seen in a neatly pressed suit, twenty-four-year-old Fred Gray was just six months out of law school in March 1955. The youngest of five children, he had grown up riding the Montgomery city buses in a triangle between school and home and his job with a newspaper. He had never himself been beaten or threatened on a bus, but he had heard more than enough insults and witnessed more than enough abuse of black passengers to last a lifetime. Like Claudette, he had vowed to study law in the North and then return home to “destroy everything segregated I could find.”

After high school, Gray worked his way rapidly through Alabama State College and then went off to law school in Ohio. True to his pledge, he returned to Montgomery soon after graduation, passed the Alabama bar exam, and opened his practice in a tiny downtown office, finding his first clients though black churches and NAACP meetings. He had lunch almost every day with Rosa Parks, who worked across the street at the Montgomery Fair department store. When E. D. Nixon suggested he take the Claudette Colvin case, Gray leaped at the chance. Since Claudette had been charged with breaking the city and state segregation laws, Gray hoped he could use the case to show they were unconstitutional. There had never been a chance before, since no one except Claudette Colvin had ever pleaded not guilty to breaking the segregation laws in a bus arrest.

Claudette’s lawyer, Fred Gray—young, smart, and “determined to destroy everything segregated I could find”

One March evening, Gray and his secretary, Bernice Hill, drove out to King Hill to meet Claudette and her parents. They sat around the Colvins’ small kitchen table sipping coffee and talking, while Hill took notes. Since Claudette was still a legal minor, one of her parents would have to file the lawsuit on her behalf. Given its importance, both parents would have to strongly support it. Gray took an instant liking to the entire family, sizing them up as brave and self-reliant. For her part, Claudette admired Fred Gray as the first person she had ever met who was doing what she herself wanted to do someday.

Gray urged all three to consider the hazards of contesting the charges in court. By pleading not guilty, Claudette would be doing more than just talking back to whites: she would be challenging Jim Crow dead-on. Her name would almost certainly be in the paper. Homes had been bombed, jobs lost, and people lynched for less. All three Colvins simply looked back at him, unshaken. Gray turned to Claudette and asked if she was sure.

“Yes, I am,” she replied.

Her quick response and the family’s unity of purpose sent Fred Gray off King Hill with a sense of hope. Whatever was to come, at least the Colvins were not people who would back down.

There had been thirteen black students on the Highland Gardens bus the day Claudette was arrested, most of them her classmates at Booker T. Washington. Gray arranged for the high school principal to issue passes for students willing to testify at Claudette’s hearing. Just before the trial, he spoke to them as a group, coaching them about what they might be asked and how best to answer.

In the days before Claudette’s hearing, black leaders rallied around her. The Citizens Coordinating Committee, a group of prominent black men and women, mimeographed a leaflet and passed it around Montgomery. Entitled “To Friends of Justice and Human Rights,” it described Claudette’s arrest and demanded that she be acquitted of charges. It also called for punishment of the bus driver and insisted on clarification of the long-standing city bus rule—constantly ignored by drivers—that said no rider had to give up a seat unless another was available.

Claudette’s hearing was held on March 18, 1955, late in the morning. A cousin drove Claudette, Q.P., and their neighbor Annie Larkin off the Hill and down to Montgomery County’s juvenile court. Claudette felt certain her troubles would be over by nightfall. “I thought Fred Gray was a very good lawyer,” she remembers. “He seemed to have prepared very well. I was confident.”

Because Claudette’s plea of not guilty to breaking the segregation law was important to every black bus rider in Montgomery, several leaders attended the hearing, including Jo Ann Robinson and the Reverend Ralph Abernathy, pastor of the First Baptist Church. It was nearly noon when Claudette and Fred Gray were summoned into the small courtroom to appear before Juvenile Court Judge Wiley Hill, Jr. Students remained in the hall, straining to hear what was going on behind the door and waiting for their names to be called.

Claudette faced three separate charges: violating the segregation law, disturbing the peace, and “assaulting” the policemen who had pulled her off the bus. Judge Hill heard testimony from Patrolmen Paul Headley and T. J. Ward, the arresting officers. Ward testified that when he’d placed Claudette under arrest, she had “fought” the officers, kicking and scratching them. “She insisted she was colored and just as good as white,” Ward informed the judge. The two officers were able to show a letter written by a white passenger on the bus that day, praising them as “gentlemen almost to the point of turning the other cheek” who spoke to Claudette in “tones so soft that I doubt if any of the other passengers aboard the bus even heard them.” When called, Fred Gray’s student witnesses offered a very different story, of two police officers confronting a teenage girl with frightening force on a packed bus. Gray challenged the laws themselves, contending that the provisions of Alabama’s laws and Montgomery’s city ordinances requiring racial segregation were unconstitutional.

Just before lunchtime, Judge Hill delivered his blunt ruling: guilty of all charges. Claudette would be placed on probation, was declared a ward of the state, and was released to the custody of her parents. He cracked his gavel, dismissing the case. As the words washed over Claudette, she felt a wave of anguish, and then everything she had been holding inside for the past two weeks came pouring out. “Claudette’s agonized sobs penetrated the atmosphere of the courthouse,” wrote Jo Ann Robinson. “Many people brushed away their own tears.”

CLAUDETTE: Now I was a criminal. Now I would have a police record whenever I went to get a job, or when I tried to go to college. Yes, I was free on probation, but I would have to watch my step everywhere I went for at least a year. Anyone who didn’t like me could get me in trouble. On top of that I hadn’t done anything wrong. Not everyone knew the bus rule that said they couldn’t make you get up and stand if there was no seat available for you to go to—but I did. When the driver told me to go back, there was no other seat. I hadn’t broken the law. And assaulting a police officer? I probably wouldn’t have lived for very long if I had assaulted those officers.

When I got back to school, more and more students seemed to turn against me. Everywhere I went people pointed at me and whispered. Some kids would snicker when they saw me coming down the hall. “It’s my constitutional right! It’s my constitutional right!” I had taken a stand for my people. I had stood up for our rights. I hadn’t expected to become a hero, but I sure didn’t expect this.

I cried a lot, and people saw me cry. They kept saying I was “emotional.” Well, who wouldn’t be emotional after something like that? Tell me, who wouldn’t cry?

The newspaper article on the facing page appeared in the Alabama Journal on March 19, 1955