I had crossed the line. I was free; but there was no one to welcome me to the land of freedom. I was a stranger in a strange land.

—Harriet Tubman

Spring and Summer 1955

THE MORNING AFTER HER HEARING, an article about Claudette’s conviction appeared in the Montgomery Advertiser. Headlined “Negro Guilty of Violation of City Bus Segregation Law,” the story reminded readers that, according to the city code, “a bus driver has police power while in charge of a bus and must see that white and Negro passengers are segregated.”

As word spread, an atmosphere of tension settled over Montgomery. “The verdict was a bombshell,” Jo Ann Robinson later wrote. “Blacks were as near a breaking point as they had ever been. Resentment, rebellion and unrest were evident in all Negro circles. For a few days, large numbers refused to use the buses . . . Complaints streamed in from everywhere.

“The question of boycotting came up again and loomed in the minds of thousands of black people,” Robinson continued. “On paper, the Women’s Political Council had already planned for fifty thousand notices calling people to boycott the buses; only the specifics of time and place had to be added . . . But some members were doubtful; some wanted to wait. The women wanted to be certain the entire city was behind them, and opinions differed where Claudette was concerned. Some felt she was too young to be the trigger that precipitated the movement.”

Was she too young? Could a rebellious teen be controlled? Who was this girl anyway? Robinson’s WPC lieutenants probed into Claudette’s background, since few adult leaders in Montgomery had ever heard of her. They already knew that her mother and father were not part of the elite social set that revolved around Alabama State College and the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. Investigation showed that Claudette Colvin was being raised by her great-uncle and great-aunt, respectively a “yard boy” and a “day lady,” as maids were called. The Colvins lived in King Hill, a neighborhood that meant “poor” or “inferior” to most who didn’t live there. And the Hutchinson Street Baptist Church, which Claudette faithfully attended, was a church for the working poor.

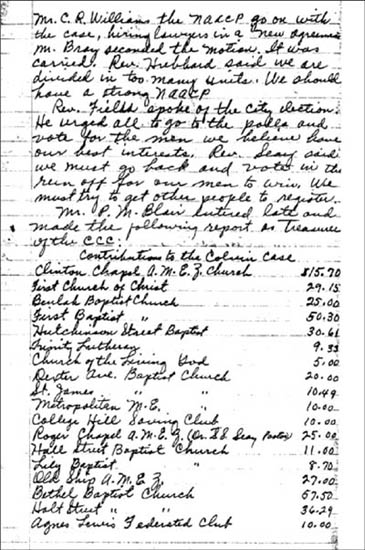

This list, probably written by NAACP secretary Rosa Parks, shows contributions made by churches to “the Colvin case”

Doubts crept in. A swarm of adjectives began to buzz around Claudette Colvin, words like “emotional” and “uncontrollable” and “profane” and “feisty.” The bottom line was, as Jo Ann Robinson tactfully put it, that “opinions differed where Claudette was concerned.” E. D. Nixon later explained, “I had to be sure that I had somebody I could win with.” So the leaders of the burgeoning Montgomery bus revolt turned away from Claudette Colvin.

About the only person not involved in these discussions was Claudette. “Nobody ever came to interview me about being a boycott spokesperson,” she later said. “I had no idea adults were talking about me and looking into my life. The only one of those people I talked to was my lawyer, Fred Gray.”

The NAACP and other Montgomery groups decided not to protest Claudette’s conviction with a bus boycott, but they did raise money to appeal the ruling, partly to clear her name and partly so they could keep using her case to attack the segregation law. Leaders were eager to appeal it all the way up to federal court. Throughout March, Montgomery’s black churchgoers were asked to drop a little extra into the collection plate for Claudette Colvin’s case. By the end of the month, fourteen churches and four civic groups had chipped in to raise almost all of what the lawyers were charging.

Virginia Durr, a wealthy and influential white Montgomerian who supported the NAACP, launched her own support drive for Claudette. She wrote Curtiss McDougall, a college professor she knew, and asked him to persuade his students to collect money for the appeal and write Claudette messages of support. “I just can’t explain how this little girl was so brave,” Mrs. Durr wrote. “It was a miracle . . . Even after being deserted [on the bus] by her other companions she still would not move. In this setting and in this town and with four big burly white men threatening her—isn’t that amazing?” More than one hundred letters soon arrived addressed to Claudette in care of Mrs. Rosa Parks, Secretary of the Montgomery NAACP.

APPEALING A LEGAL DECISION

The U.S. legal system begins with city and county courts, goes on to state courts, then to federal courts, and finally to the U.S. Supreme Court. If a person does not agree with a court decision, she or he can usually appeal the case to a higher court.

It is tempting to appeal, to take a second chance. But lawyers are expensive, and winning cases on appeal is not always easy, as judges are sometimes reluctant to reverse the decisions of their colleagues on lower courts.

In Claudette’s case, black leaders decided to appeal a decision made in Montgomery’s juvenile court to the next level, Montgomery Circuit Court, which was still within the state of Alabama’s court system.

On May 6, 1955, Gray went back to Montgomery Circuit Court to appeal Claudette’s conviction. After hearing testimony, Judge Eugene Carter dropped two of the three charges against Claudette—disturbing the peace and breaking the segregation law. But he kept the third, her conviction for “assaulting” the officers who had lifted her out of her seat and dragged her off the bus. He sentenced Claudette to pay a small fine and kept her on probation in the custody of her parents.

It was a dispiriting outcome on two scores. First, Montgomery’s black leaders had hoped to keep using Claudette’s case in higher courts to challenge the constitutionality of segregated bus seating. But now that Judge Carter had shrewdly dropped that charge, there was nothing left to appeal that was specifically about segregation. All the leaders but Gray lost interest in appealing Claudette’s case any further.

Second, Claudette still had a criminal record. She had been convicted of assaulting police officers, information that would forever blemish her job applications, credit record, and school transcripts. By keeping the assault charge, Judge Carter deprived Claudette of peace of mind. Now she feared that people would see her as a juvenile delinquent, a criminal, someone with a mark against her name. Had she thrown away her dreams by taking a stand?

As cold, rainy weather set in, blacks returned to the buses. Claudette went back to school to finish out the last few weeks of her junior year. She soon found that attitudes at Booker T. Washington had hardened against her. It was easier to see the “bus girl” as a troublemaker than as a pioneer. More and more students mocked her now. Shaken, but defiant to the core, Claudette battled back—in her own way.

CLAUDETTE: One Saturday I was home by myself waiting around for an appointment with the beautician to have my hair straightened. And then it hit me: Why am I wasting my time and two good dollars straightening my hair so I can look more white? I went straight into the kitchen and washed it. Then I pulled it out into little braids while it was still damp. When I was done I looked like I was about six years old.

My mother came in the door to ask me why I didn’t show up at the beauty shop. Then she took one look at my hair and said, “What?”

Making those pigtails was the strongest statement I could make in that school. If I had cut all my hair off, they probably would have locked me in an institution. Miss Nesbitt was right: My hair was “good hair,” no matter what. By wearing it natural I was saying, “I think I’m as pretty as you are.” All of a sudden it seemed such a waste of time to heat up a comb and straighten your hair before you went to school. So I just quit doing it. I felt very emotional about segregation, about the way we were treated, and about the way we treated each other. I told everybody, “I won’t straighten my hair until they straighten out this mess.” And that meant until we got some justice.

When I went to school the next Monday, people were cold shocked. Teachers asked me, “Why would you do such a thing?” They wouldn’t let me be in the school play because of how I wore my hair. Classmates said I was still grieving Delphine. I tried to put it out of my mind, but no one else would.

At that time I had a boyfriend named Fred Harvey. He was in my homeroom and I used to help him with his homework. He was really sweet. He’d take me to the movies and save enough money so he could send me home in a taxi rather than put me on the bus. But he was just stunned. He kept asking me, “Why, why? Why won’t you straighten your hair?” I told him I thought my hair looked “African,” and I was proud of it. That really got him. Back then we never used the word “African.” Africa was the jungle, Africa was Tarzan. We were supposed to be ashamed of our African past. But Africa made me proud. That whole spring, until school was out, just about all I heard from anybody was “You’re crazy. You’re crazy. You’re crazy.”

“FROM THE TIME CLAUDETTE GOT ARRESTED she was the center of attention,” remembers Alean Bowser, one of Claudette’s classmates. “But the attention was directed in the wrong way. Kids were saying she should have known what would happen, that she should have got up from her seat. Everything was reversed, everyone blamed her rather than the people who did those things to her. They would whisper as she went down the hall. It was mean.

“What she did with her hair just made it worse. She had always kept her hair neatly styled. And then she just came to school one day with cornrows . . . It was shocking. Kids had already pulled back from her. They were already whispering she was crazy and things like that. I was shocked, too, but I wasn’t embarrassed by what she did with her hair. I was on her side. Claudette was a wonderful person, with a mind that was mature beyond her years. One day our teacher told us to write down on a piece of paper what we wanted to be when we grew up and pass it up front. Claudette wrote, ‘President of the U.S.’ I think she meant it. We should have been rallying around her and being proud of what she had done, but instead we ridiculed her.”

School recessed for the year and the sun set about baking central Alabama. As the long, buggy summer days drifted by, Claudette spent much of her time at King Hill Park, sitting outside on the veranda, crocheting and talking to her cousin, dragging her chair around to follow the shade. Often she helped her mother take care of her white family’s three young children. Every now and then she scraped up a babysitting job. Nights seemed even slower. Dances and parties were out—what if something went wrong? One false move, or one malicious report, and she was a parole violator. Claudette lost touch with her friends, stayed home, and turned inward.

At least there was still church. On Sundays after services at Hutchinson Street Baptist, she would go across town to Rosa Parks’s NAACP youth meetings. Mrs. Parks had appointed Claudette youth secretary, which meant keeping attendance and membership records and putting out notices. The meetings were held at the redbrick Trinity Lutheran Church, pastored by the Reverend Robert S. Graetz. He was the only white minister in Montgomery with an all-black congregation.

CLAUDETTE: I only went if I could get a ride, because I didn’t want to ride the bus anymore. If I couldn’t get a ride back, I’d stay overnight at Rosa’s—she lived in the projects across the street. Rosa was hard to get to know, but her mom was just the opposite—warm and talkative and funny. We would stay up all night gabbing, sometimes while Rosa pinned wedding dresses on me that she was altering for work. Rosa’s mother knew all sorts of horror stories about black girls getting mistreated. There was nothing we couldn’t talk about.

Rosa Parks was like two different people inside and out of the meetings. She was very kind and thoughtful; she knew exactly how I liked my coffee and fixed me peanut butter and Ritz crackers, but she didn’t say much at all. Then, when the meetings started, I’d think, Is that the same lady? She would come across very strong about rights. She would pass out leaflets saying things like “We are going to break down the walls of segregation.”

I might have had more fun if the meetings had been in my neighborhood. The children in the NAACP youth group weren’t like the students I went to school with. Their parents were professionals; these children went to private schools. Whenever they said they planned to go North for an education after they graduated, Rosa would scold them. “Why should your families have to send you North? Our colleges right here could offer a good education, too—but they’re segregated.” Rosa kept inviting me to tell my bus arrest story to the kids there, but after a while they had all heard it a million times. They seemed bored with it.

IT WAS DURING ONE OF THOSE SUMMER VISITS across town that Claudette met someone who actually listened—or seemed to. While watching a baseball game in a park, Claudette was joined by a light-skinned black man. She judged him to be maybe ten years older than she was, married, he said, but separated from his wife and living with his mother. He said he was a Korean War veteran, and backed up his claim with lively stories from places in distant parts of the world.

EMMETT TILL

What happened to Emmett Till in the summer of 1955 was a horrible reminder of how much resistance there would be to racial integration in the South. Till was a fourteen-year-old Negro boy from Chicago who had gone to Mississippi to visit relatives in a small town. In August 1955, he allegedly whistled at a white store clerk and said “Bye, baby” to her as he left the store. Three nights later he was kidnapped. Three days after that, his body was found floating in a river, wrapped in barbed wire and grotesquely mutilated. Two white men were arrested but acquitted by an all-white jury.

The savagery of the crime sent a chilling message. “We talked about it a lot that summer and in school the next fall,” remembers Claudette. “There had been lynchings and cross burnings before, but this was a much stronger warning. Emmett Till was our age.”

CLAUDETTE: I liked talking to him. He was the first person to understand my hair. Everyone else kept saying I was crazy, or “mental,” but he got it. He said it was impossible for black people to have really straight hair anyway; he had seen Asian women with straight hair all the way down to their feet. No black woman could ever grow hair like that no matter how she tried. He kept telling me to ignore what people were saying about me. I really needed to hear that. He was easy to talk to. I could relate to him. I would say things like “The revolution is here—we need to stand up!” and he would agree. But all the time I knew that I was getting in over my head. He was so much older than me, and had so much more experience. I knew I was getting into a situation I couldn’t handle, but it was hard to stop.

THE SLOW, SULTRY SUMMER finally came to an end when, just after Labor Day, Claudette celebrated her sixteenth birthday and returned to Booker T. Washington High for her senior year. Her legal case had died with the appeal decision, and Claudette had lost contact with all the adult black leaders except Rosa Parks. Still, riding the bus continued to anger and humiliate blacks throughout Montgomery, and impatience was mounting. Leaders such as E. D. Nixon and Jo Ann Robinson kept looking for the catalyst—the “right” person or event—that would spark citywide action.

Emmett Till and his mother, Mamie Bradley

On October 21, a second teenager, eighteen-year-old Mary Louise Smith, defied a Montgomery bus driver’s command. She had left home early that morning to collect the twelve dollars owed her by the white family for whom she had worked the week before. But when she finally reached their house on the other side of town, they weren’t home. Now she was out not only her wage, which her family needed, but also the twenty cents for round-trip bus fare. A week of work and a trip across town for nothing: that’s what she was thinking on the bus ride home when a redhaired woman appeared in the aisle by her seat and ordered her to get up and move back.

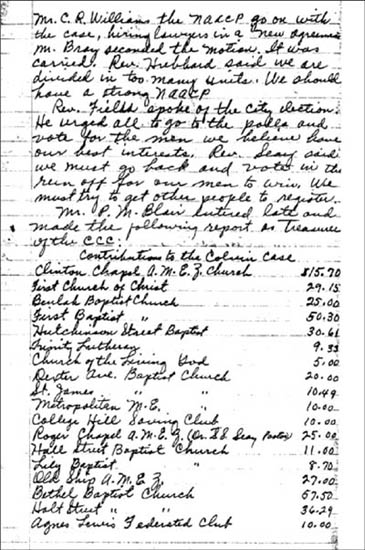

Mary Louise Smith, graduation photo, 1955

At St. Jude School, the nuns had taught Mary Louise and her siblings to respect all people regardless of their skin color, and she did. But she was angry that day. She was thinking, It’s the bus driver’s job to ask, and to ask politely. Muttering a rare profanity, she crossed her legs, squirmed down in her seat, and made herself very still. She heard the bus driver’s command to move, but she refused. And refused again. Next came the driver’s radio call, and within minutes, a policeman entered the bus and arrested her.

Mary Louise was taken downtown, booked, and jailed. She was released two hours later, when her father arrived and paid the fourteen-dollar fine. It happened so quickly and quietly that there was no newspaper publicity. By the time E. D. Nixon and other black leaders heard about Mary Louise Smith, her fine had already been paid and it was too late to mount a legal challenge.

But that didn’t stop people from talking. Another teenage girl had been arrested on the bus. Who was she? Where was she from? What church did her family go to? Who were her parents? Where did they live? Soon the rumor mill was spinning out gossip that the Smith girl’s father was a drunk and the family lived in a squalid shack.

The truth was much different. Mary Louise later said she never in her life saw her father drunk. For one thing, he was too busy working to drink much. After Mary Louise’s mother died, in 1952, Frank Smith took a second job to support his six children. Hardly a shack, the Smith home was a two-story, three-bedroom frame house in a working-class neighborhood. But Mary Louise Smith, the second teenager with the nerve to face down Jim Crow on a city bus, was, like Claudette, branded “unfit” to serve as the public face of a mass bus protest.

During the summer and fall of 1955, Montgomery’s adult black activists thought hard about the buses—which looked increasingly like Jim Crow’s Achilles’ heel. Each considered what to do in his or her own way. Jo Ann Robinson, E. D. Nixon, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and others continued to meet with city and bus officials, consistently pressing for black drivers, courteous treatment, and a revised seating plan. Every polite refusal increased their resolve. Dr. King thought the officials were digging their own grave. “The inaction of the city and bus officials after the Colvin case would make it necessary for them . . . to meet another committee, infinitely more determined,” he later wrote.

Rosa Parks and Fred Gray met for lunch nearly every day, often talking about what could be learned from Claudette’s case that could end segregation on the buses. In July, Mrs. Parks slipped away for a two-week workshop on interracial relations at the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee. Here, for the first time, she saw blacks and whites treated as equals. She returned saying it had changed her life.

The time was ripe for change. There was a growing impatience with segregation. Claudette had crossed a line, proclaiming that at least one young Alabaman would not share her future with Jim Crow. Seven months later, Mary Louise Smith had joined her. Now, a year and a half after Brown v. Board of Education, a few brave young people were demanding a different future. Education may have been the way up, but transportation was the way out. If they were branded “uncontrollable” or “emotional” or even “profane,” so be it. Claudette and now Mary Louise Smith had shown through their courage that at least some young people were ready to act.

Rosa Parks with E. D. Nixon (at left). At last the African-American community of Montgomery was united and ready for action