Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave,

I am the dream and the hope of the slave.

I rise

I rise

I rise.

—Maya Angelou, “Still I Rise”

ON DECEMBER 2, 1955, tens of thousands of black Montgomery residents studied an unsigned leaflet bearing a brief typewritten message. It began: “Another Negro woman has been arrested and thrown in jail because she refused to get up out of her seat on the bus for a white person to sit down. It is the second time since the Claudette Colbert [sic] case that a Negro woman has been arrested for the same thing. This has to be stopped.” It concluded:

We are, therefore, asking every Negro to stay off the buses Monday in protest of the arrest and trial. Don’t ride the buses to work, to town, to school or anywhere on Monday. You can afford to stay out of school for one day if you have no other way to go except by bus. You can also afford to stay out of town for one day. If you work, take a cab, or walk. But please, children and grown-ups, don’t ride the bus at all on Monday. Please stay off the buses Monday.

The author was Jo Ann Robinson, who had been up all night with two student assistants at Alabama State, feverishly running the flyers off on the college’s mimeograph machine and bundling them into packages. When they finished, she placed a phone call to activate a network of distributors already in place. Soon twenty or so allies were stationed at their posts throughout the city, craning their necks watching for Robinson’s car to come into view so they could receive their bundles of flyers and start passing them out in schools, offices, factories, stores, restaurants, and beauty parlors. “Read it and pass it on!” the distributors instructed and sped off. Two of Robinson’s most trusted lieutenants were Claudette’s favorite teachers, Miss Nesbitt and Miss Lawrence. By nightfall most blacks in Montgomery knew what was up. Those who didn’t know about the one-day bus boycott read about it in the next morning’s Montgomery Advertiser, in a story leaked by E. D. Nixon to a trusted reporter.

The “other Negro woman” arrested was Rosa Parks. Just the afternoon before, Mrs. Parks had refused a driver’s command to give up her seat to a white passenger on a crowded bus. Then, as had been the case with Claudette, the driver called the police, officers boarded, and one asked her, “Why don’t you stand up?” She replied, “Why do you push us around?” He answered, “I don’t know, but the law is the law and you are under arrest.”

There the similarity to Claudette’s arrest ended. Rather than being grabbed by the wrists and jerked up from her seat with belongings flying everywhere, Rosa Parks stood up. One officer took her shopping bag, the other picked up her purse, and they escorted her off the bus and into a patrol car. She sat in the backseat alone, her hands uncuffed, as they drove to police headquarters and then to city hall. After her fingerprints were taken and the paperwork completed, she was allowed to telephone her family.

She was charged only with disorderly conduct, not with breaking the segregation law. She was not jailed. Soon E. D. Nixon and two white activists, Clifford and Virginia Durr, hurried downtown, paid her bond, and took her home, where Fred Gray later met her and agreed to be her lawyer. The next Monday morning, Mrs. Parks was found guilty in a brief court hearing. She paid a ten-dollar fine and was released. Gray told the judge to expect an appeal. When Mrs. Parks walked out of the dim courthouse and into the cool, bright morning, she was surprised to find several hundred cheering supporters waiting for her.

Claudette had lit the fuse to a powder keg of protest, but her rebellion had caught black Montgomery by surprise. Now, nine months later, Rosa Parks was embraced by a community ready for action. Claudette had given them the time to prepare. As Fred Gray later said, “I don’t mean to take anything away from Mrs. Parks, but Claudette gave all of us the moral courage to do what we did.”

Married and in her early forties, Rosa Parks was widely known as an activist through her work with the Montgomery NAACP. As a seamstress at a downtown department store, she repaired, altered, and steam-pressed clothing—work known and respected by both the black professional class and ordinary workers. She was light-skinned but not white. She may not have gone to the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church—she was a Methodist—but she would have been accepted in any congregation. She bridged classes.

What she wasn’t may have been just as important to Montgomery’s black leadership, the preachers and teachers and ASC women and E. D. Nixon. She wasn’t a teenager. Hardly “feisty” or “emotional,” as Claudette was rumored to be, Rosa Parks struck almost everyone she met as a contained, pleasant, committed, and levelheaded individual. She was safe.

And she wasn’t pregnant. Neither was Claudette when she had been arrested and people started talking about her, but now she was, and she would have to deal with it.

CLAUDETTE: The first few months I hoped and prayed and pretended it wasn’t true, but it was. I had so little information about sex. I wasn’t sexually active at all. I had never gone very far with my boyfriend, and my parents had never talked to me about sex. I would hear other girls say, “Well, I didn’t get pregnant my first time, or the second.” It had only happened once with this man, and I was so uninformed that I wasn’t even sure that what we had done could get me pregnant.

But it had, and I thought my mom was going to have a heart attack when I told her. We thought about an abortion, but it was illegal, and the only woman we had heard of who did abortions was supposedly connected with the police department. Besides, my mother was convinced God wouldn’t forgive you for an abortion. My dad threatened to kill the father—he was so much older than I was. Then my dad got worried that the father’s wife’s family was going to accuse me of breaking up their marriage and come after us. My parents insisted that I not tell anyone who the father was. I wanted to tell, to explain what had happened to me so that people would understand, but I gave in and kept quiet.

My mom just took over my life at that point. Usually I was stronger, but right then I was easy to control. Of course I couldn’t marry the father; I didn’t love him and he was already married. My boyfriend, Fred Harvey, came to our house and asked to marry me, but my mother said he would just be doing it out of pity. I wanted to say yes, but I backed down.

We decided I’d keep my pregnancy a secret as long as I could so I wouldn’t get kicked out of school. The rule at Booker T. Washington was “If you’re pregnant, you’re out.” Then, when Christmas break came, I would tell the school I was sick and go to Birmingham and live with my birth mother and have the baby there. After that I would leave the baby with her for a while and come back to Montgomery and finish high school. I would only have one semester left.

But I started showing too early. Late in the fall a few girls caught on. They’d say, “I thought you had more sense.” I didn’t have any answer to that. The teachers always had an eye out for pregnant girls—it was very common. They knew the signs. So one day I got called down to the office. I went in to see the principal, Mr. Smiley. I said, “I know why I’m here; you don’t have to bother saying it,” but he did anyway. And he added, “Don’t come back after Christmas break.”

So we had to change strategies. Our new plan was for me to have the baby in Birmingham and finish school there. I had never officially changed my last name on my birth certificate to Colvin—it still said I was Claudette Austin. So I could enroll as Claudette Austin and finish high school in Birmingham.

One day a few weeks before Christmas, I was at home, trying to get ready in my mind for all the changes to come—changes in my body, becoming a mother, not going to Booker T. Washington, moving away from my Montgomery family—when a neighbor girl walked over from across the street carrying a piece of paper. She handed it to me and said, “You gotta read this.” The three of us—her, me, and Mom—stood out in the front yard reading it. It was the boycott leaflet: “Don’t ride the bus on Monday.” Right away I saw my name—misspelled: “Claudette Colbert.” My first thought was, If they had just called me, I could have at least reminded them how to spell my name.

But it didn’t say who the Negro woman was who got arrested. When I heard on the news that it was Rosa Parks, I had several feelings: I was glad an adult had finally stood up to the system, but I felt left out. I was thinking, Hey, I did that months ago and everybody dropped me. There was a time when I thought I would be the centerpiece of the bus case. I was eager to keep going in court. I had wanted them to keep appealing my case. I had enough self-confidence to keep going. Maybe adults thought a teenager’s testimony wouldn’t hold up in the legal system. But what I did know is they all turned their backs on me, especially after I got pregnant. It really, really hurt. But on the other hand, having been with Rosa at the NAACP meetings, I thought, Well, maybe she’s the right person—she’s strong and adults won’t listen to me anyway. One thing was for sure: no matter how I felt or what I thought, I wasn’t going to get my chance.

DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., rose early the morning of Monday, December 5, rushed to his picture window, and peered out at the first buses as they moved past his house. They were nearly empty. Usually they were filled with maids and black schoolchildren. Excited, he jumped in his car and drove around Montgomery to inspect other buses during the morning commute. In an hour of driving, he saw a total of only eight black passengers on the buses. Clearly the message “please . . . don’t ride the bus at all on Monday” had reached almost everyone.

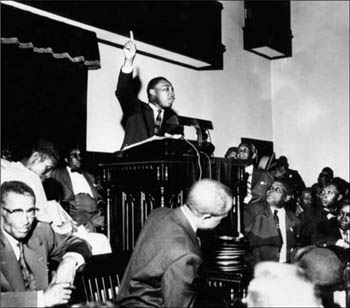

The Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., was a passionate speaker. For Claudette, his speeches “just brought out everything you wanted to say to a white person”

That evening, a “mass meeting” was held at the Holt Street Baptist Church, to celebrate the day’s triumph and to plan for the future. By 7:00 p.m., nearly one thousand people were wedged shoulder to shoulder inside the brightly lit church, while four thousand more gathered outside in the chilly darkness to hear songs and speeches and prayers broadcast through makeshift speakers.

Dr. King, elected just that morning as president of the Montgomery Improvement Association, was the main speaker. It was his first major public speech that wasn’t a church sermon, and he needed to inspire this crowd. When introduced, he grasped the sides of the pulpit and took a moment to collect himself. Turning to Rosa Parks, seated behind him in a special place of honor, he began, “Just last Thursday . . . one of the finest citizens in Montgomery . . . was taken from a bus—and carried to jail and arrested—because she refused to give up—to give her seat to a white person . . . And since it had to happen, I’m happy it happened to a person like Mrs. Parks, for nobody can doubt the boundless outreach of her integrity. Nobody can doubt the height of her character, nobody can doubt the depth of her Christian commitment.”

MLK’S BOYHOOD BUS EXPERIENCE

Martin Luther King, Jr., knew firsthand about bitter times on the bus. When he was fourteen, he traveled from Atlanta to a Georgia town to take part in a speech contest. On the way home a white bus driver ordered King and his teacher to give up their seats to white riders. King refused at first, but his teacher persuaded him to give way. He had to stand for several hours. Twenty years later he called it “the angriest I have ever been in my life.”

Toward the end of his address, Dr. King delivered lines for which he would be remembered. “And we are determined here in Montgomery,” he said, his voice rising in intensity, “to work and fight until justice runs down like water and righteousness like a mighty stream.” His passionate words rocked the church. “Standing beside love is always justice,” he continued. “Not only are we using the tools of persuasion—but we’ve got to use the tools of coercion.” When King sat down to thunderous applause, the crowd inside and outside was ready to act. The Reverend Ralph Abernathy took the pulpit and read a resolution asking that all citizens refrain from riding buses operated by Montgomery City Lines, Inc. “All in favor of the motion, stand,” Abernathy said. Everyone in the room climbed to their feet.

It was the first of millions and millions of steps to come. The Montgomery bus boycott was born.

CLAUDETTE: Mom and Velma went to the mass meeting, but I stayed home. I was in a different mind. I was depressed, I was pregnant, I had been expelled from school, and I was leaving home. I had already taken the NAACP records back to Rosa’s house and left them with her mother.

Right before Christmas, Mom drove Velma and me to Birmingham. We had Christmas there with my birth mother’s family and visited some friends. Then Mom and Velma went back to Montgomery. I was on my own.

That was an important time for me. My parents were so strict, especially Mom. She tried to make all the decisions for me. Being away from her in Birmingham gave me a chance to clear my head. I thought a lot about what was going down in Montgomery.

A protest of some kind had been coming on for a long time. Black people weren’t going to take segregation much longer. If you were black, you experienced abuse every day of your life. Every day. You couldn’t even walk through the park without looking over your shoulder for a policeman. The bus boycott was a way of expressing anger at the system at last.

I was thinking, Where are we going? In church the adults kept saying Reverend King would eventually be driven out of Montgomery or they’d murder him, since whites would never give in. People were saying the boycott wouldn’t succeed. But I was glad it was happening. So many black people were just struggling from day to day—most of us. We had to do it. There had been so much injustice, from Jeremiah Reeves to all the horror stories involving black women abused by white men, to my own arrest. I really wanted to be a part of the boycott.

I also used the time to clear my head about my own life. When I left Montgomery, everyone was saying I was “mental” and “crazy.” But I wasn’t. The most horrifying part of my last year hadn’t been finding out I was pregnant, or getting kicked out of school. It was the sound of the jailer’s key in the cell door. It was my arrest. And I had gotten through that. The pregnancy was, in a way, a chance to regroup and think about my life. I was a healthy young woman and I was going to have this baby, and I would deal with motherhood when it came. I could take the G.E.D.—a high school equivalency exam—in Montgomery and get my diploma that way.

I only stayed in Birmingham about two weeks. I missed my dad, Q.P. He was always there for me. Besides, I’d had justice on my mind for a long time. Just because I was pregnant didn’t change my mission. I had been talking about revolution ever since Jeremiah Reeves. I wanted to be part of the bus boycott even if I couldn’t be a leader. I had helped get all this started.

So I went back home.