We are going to hold our stand. We are not going to be a part of any program that will get Negroes to ride the buses again at the price of the destruction of our heritage and way of life.

—W. A. “Tacky” Gayle, mayor of Montgomery

WITH THE TURN of the new year of 1956, Montgomery throbbed with excitement. Day by day, reporters and photographers poured into town to cover the Negro bus protest in the heart of Dixie. As the boycott entered its second month, black leaders continued to press for the same three modest changes that Jo Ann Robinson and others had requested two years earlier—which did not include integrated seating—but city officials wouldn’t budge. “Give them an inch and they’ll take a mile,” they told one another. The City Lines bus company declared the proposed changes illegal and said that, unfortunately, their hands were tied.

Members of Montgomery’s black community gather at the Holt Street Baptist Church in support of the boycott

Mass meetings continued at black churches every Tuesday and Thursday night. Young, round-faced Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who urged boycotters to refrain from violence and seek charity toward whites in their hearts, inspired crowds with stirring speeches that often included ideas and philosophies from distant times and places. He talked about the power of love to change the world. “He had poetry in his voice, and he could snatch scripture outa the air and make it hum,” said E. D. Nixon, who admitted “he was saying it better ’n I ever could.” King began to emerge as a charismatic national figure.

Determined to apply economic pressure peacefully, black protesters let the nearly empty buses rumble on by like green ghosts, ignoring the doors that snapped open invitingly at the corners, and devised their own transportation system. Coached by leaders of Baton Rouge’s bus boycott of 1953, the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) designed an alternative to the buses on the scale of a wartime military transport system, moving tens of thousands of maids and yard men and clerks and students around Montgomery’s far-flung neighborhoods every day. And it was entirely voluntary—it ran on dedication, generosity, and hope.

THE MONTGOMERY IMPROVEMENT ASSOCIATION

Leaders believed that a new organization was needed to run the boycott, so they created the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA). Determined to avoid friction between established black leaders, they nominated as president a newcomer, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. “Well, if you think I can render some service, I will,” he replied. A board of twenty-five directors was named.

After thousands voted to continue the boycott beyond one day, the MIA had a lot of work to do. They had to design the car pool, put it in motion, and pay for it. Mass meetings were held twice a week to keep spirits up and collect donations. As the boycott rolled on, donations poured in from all over the country—eventually enough for the MIA to buy more than thirty station wagons.

Some teens organized their social lives around the mass meetings. Annie Larkin, then sixteen, recalls, “I’d go home from school, get my homework done, and my grandmother would have dinner ready so my aunt and I could go to mass meetings together. I went every Tuesday and Thursday night, no matter where.”

The MIA network was unveiled in detail at a mass meeting on December 12. There would be forty-two morning pickup “stations” and forty-eight evening stations scattered throughout Montgomery. These points had been carefully plotted on maps by mail carriers, the workers who knew the city best. The central dispatch station would be a black-owned downtown parking lot, manned by an on-call transportation committee. The “buses” would be a giant car pool consisting of ordinary people’s automobiles. Car owners were asked to lend their vehicles to the MIA car pool so that other people could drive them around town. For most people, especially if they had little money, having a car was a proud symbol of status. Letting total strangers drive one’s car around all day was a hard thing to ask, but nearly two hundred people turned over their keys to the boycott.

Here’s how it worked: a maid needing to get across town to her white employer’s home would walk to the morning station nearest her home and wait for a ride. After work she would walk to the nearest night station to be picked up and driven to a drop-off point nearer her home. Since it was against the law for private cars to charge fares like licensed taxis, the network would be paid for by donations collected at the mass meetings. Most of the rides would be free.

Though the network was elegantly designed, there were not enough seats in the car pool to replace an entire city bus system. Thousands of black workers, including many who were elderly and some who were disabled, set out from home in the predawn darkness and walked miles each day. Some preferred to walk to show their support for the boycott rather than accept a ride even from the MIA car pool. One MIA driver told the story of having come upon an elderly woman hobbling along the road. “Jump in, grandmother,” he said to her, pushing open the door. She waved him on. “I’m not walking for myself,” she said. “I’m walking for my children and my grandchildren.”

The third month of the boycott and another day of walking

Family members made enormous sacrifices and sometimes hobbled home with barely enough energy to eat supper. And family chores like shopping had to continue. That meant more steps. The foot-weary warriors told their stories at the mass meetings, inspiring and encouraging one another to keep walking.

Many were initially skeptical of the boycott. “When they first sent the leaflets saying ‘don’t ride the bus,’ I was worried about my momma,” remembers Alean Bowser. “I got angry, and I said they’d better not do anything to her. I thought she’d still go on riding the bus because she did housecleaning and she worked far away from home. But then they had worked out this whole plan of having people to drive and pick up. I got behind it. I and three other girls from my typing class at school started working at the Baptist Center, typing up and mimeographing lists of the people who were driving in the bus boycott. We had to make the list every third night in order to keep the information current. They had stations downtown. Who was driving this direction and that direction. I had to call the drivers and make sure they were still willing and available. And people in most families had walking jobs, too. I was appointed to walk downtown and pay our bills. But I could use the network for that, too.”

Boycott supporters climb out of one of the dozens of station wagons that were purchased during the 381-day protest. Many of the vehicles were assigned to churches

CLAUDETTE: When I got back to Montgomery, of course I stayed off the buses. Mostly I rode with my mom in a used Plymouth Dad bought for her. She needed it, because she worked way up out of town in a place the car pool didn’t go to.

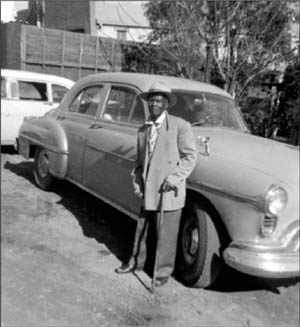

Q. P. Colvin, Claudette’s dad, bought a car for the family during the boycott

Dad was very frugal. He saved enough to buy a TV set, too, so we could keep up with the boycott. We’d watch the news every night. The boycott was always the headline—it was the biggest story in the South. I also read Jo Ann Robinson’s editorials in a little newsletter that came every month.

The people Mom worked for were sympathetic to the boycott. The first sign of this was they didn’t fire Mom when they found out I was arrested. They weren’t rich; they were just average people. They paid my mom three dollars a day and bus fare. The lady used to bring her home after work on the days when Mom didn’t drive.

The boycott was relatively easy for people on King Hill because we already had our own community transportation system in place. We were isolated—just three little streets on top of a hill on the edge of town. We had no stores up there, so we had to go through white neighborhoods to shop downtown. To get off the Hill, three or four people would pitch in to pay someone a quarter to drive them to and from work. They’d drop the maids off house by house because everybody was going in the same direction.

My family duties increased during the boycott. Mom was gone a lot, because she used her car to drive people places. We didn’t donate our Plymouth to the boycott because Mom needed it to get out of town for work, but since we had a car people were constantly coming around to say, “Mary Ann, can you take me and a couple of others to this place or that?” Dad didn’t drive and I didn’t have a license yet, so I did more cooking and cleaning and shopping and laundry while Mom drove. I had several cousins who drove taxis, and they’d come and take me to town when I wanted. A lot of people volunteered their cars for the boycott and dipped into their savings to buy gasoline during that time. Everyone pulled together.

WHITE SUPPORT OF THE BOYCOTT

Not all white Montgomerians opposed the boycott, and not all favored racial segregation. A small but determined minority of white citizens assisted the car pool, drove their black employees to and from work, and sometimes donated money to the boycott. Among the best known were Robert Graetz, the pastor of Trinity Lutheran Church, and Clifford Durr, a lawyer who assisted Fred Gray in his legal cases. His wife, Virginia Durr, also provided support in many ways.

A few whites dared to express their support publicly. Juliette Morgan, a librarian, wrote in a letter to the editor of the Montgomery Advertiser, “It is hard . . . not to be moved with admiration at the quiet dignity, discipline, and dedication with which the Negroes have conducted their boycott.”

The death threats began immediately, by phone and mail. They increased month by month. People hurled stones at Morgan’s picture window and sprinted up to ring her doorbell again and again in the dead of night, shattering her sleep. She lost many friends. About a year after her letter was published, Juliette Morgan took her own life.

I went to the mass meetings when they were at churches on the other side of town, where people wouldn’t recognize me. I went to a lot of them, more than once a month. I heard Dr. King speak, and felt the people rally around him. Those speeches he made just brought out everything you wanted to say to a white person. People were kicking you when you were down every day, and his words made you feel stronger. I sat in the back, far away from the speechmakers, wearing big shirts to cover my growing stomach. The leaders sure weren’t going to invite a pregnant teenager up onstage during a mass meeting. It bothered me to be shunned, but I was an unwed pregnant girl and I knew how people were. People who recognized me would ask, “Who’s the father?” I’d answer, “None of your business.”

BY LATE JANUARY, the City Lines bus company was losing $3,200 a day. They had been forced to lay off drivers and shut down several bus routes just to stay in business. Inspired at mass meetings by the testimony of elderly people who walked great distances and poor families who donated money for gasoline, protesters kept walking and vowed to do so until justice came. Many who owned cars continued to offer them to the car pool and volunteer as drivers. Thousands used the car pool each day, and thousands more walked to work and school and the downtown stores.

Montgomery motorcycle police keep a close eye on a downtown parking lot, one of the many busy transfer points for the MIA car pool

In desperation, Mayor W. A. “Tacky” Gayle turned up the heat. Police were instructed to crack down on drivers, stopping them and questioning them at every opportunity. Dr. King was arrested on January 26 for going thirty miles per hour in a twenty-five-mile-an-hour zone. He spent a night in jail for the first time in his life. Three days later someone hurled a bomb through his front window, causing extensive damage but injuring no one in his family. At a mass meeting he said, “If I am stopped, this movement will not stop, because God is with this movement.”

SEPARATE BUT EQUAL?

In 1896, in a famous court case known as Plessy v. Ferguson, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the state of Louisiana could racially segregate its buses, streetcars, and trains without violating the U.S. Constitution as long as the separate sections of compartments were “equal.”

Separate but equal became the legal basis for segregation throughout the South. But the idea that the schools, parks, hotels, restaurants, and sections of buses and trains were “equal” was a sham. In 1900, $15.41 was spent on each white child in the public schools versus $1.50 per black student. The ratio was the same forty years later.

It was this idea—separate but equal—that the Supreme Court justices struck down in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka in 1954. The justices wrote, “We conclude, unanimously, that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place.” But did it still have a place in transportation? Sixty years after Plessy v. Ferguson, Fred Gray and the other lawyers were fashioning a lawsuit to insist that the answer was no.

The attacks continued. In early February a stick of dynamite landed on E. D. Nixon’s front lawn. About that time Jo Ann Robinson’s picture window was shattered by a huge rock, which her neighbors said had been thrown by a policeman. Days later two men dressed in full police uniform walked into the carport beside Robinson’s house and scattered acid over her Chrysler sedan. According to neighbors, when they were finished, the pair calmly walked to their squad car and drove away. The substance burned holes the size of silver dollars through the vehicle’s top, fenders, and hood. Neighbors told Robinson what they saw but were too frightened to make an official report of the crime.

With violence mounting and negotiations stalled, protesters asked one another how this would end. While everyone longed and prayed for success, many held private doubts—it was hard to imagine that whites would ever give up control.

Fred Gray thought he saw the way out—it was the same path he had envisioned from the day he heard of Claudette’s arrest. Why not go to court and sue the city of Montgomery and the state of Alabama, arguing that if segregated schools were unconstitutional—as the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled in Brown v. Board of Education—then weren’t segregated buses? Instead of politely asking for modest reforms in seating patterns and more courteous behavior from the drivers, why not try to obliterate the segregation laws in court? If judges agreed, the city would have to give up. Once the buses were integrated, there would be no need for a bus boycott.

Gray, like the NAACP lawyers in New York who were closely following the boycott, was tired of playing defense. He wanted to mount a legal attack on behalf of all black riders as a class-action suit, not just to defend protesters who got arrested and charged as criminals one by one. Success would depend on putting the right case in front of the right judges in the right courtroom.

Since judges representing the state of Alabama and the city of Montgomery court systems were all but certain to be hostile, the lawyers knew that their only chance was to argue their case in a federal court, where judges might listen with an open mind to an antisegregation suit offered by black lawyers.

Any lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of a state law was supposed to be heard by a panel of three judges in a federal court—that was the rule. Whether federal judges based in Alabama would actually follow it and hear the case was the big question. If they did, the suit would still be heard and decided in Alabama, but the judges would represent the United States government, not the state of Alabama or the city of Montgomery.

The Montgomery Improvement Association voted to let Gray go ahead with the lawsuit—the “second front,” as it came to be called—and raise money to pay for it. Gray went to New York to huddle over legal strategies with NAACP lawyers, then returned to Montgomery and filed the suit in the federal building. To his delight, the suit was accepted as a constitutional challenge to state law and assigned to a threejudge federal panel.

Next Gray began to look for plaintiffs—those people whose names would appear on the lawsuit and who would testify in court. The idea was to put on the witness stand black passengers who would testify to how Jim Crow had made their lives miserable while they were just trying to get from place to place.

Courage would be their number one requirement. They would be placing their lives in grave danger, and the lives of those they lived with. From their seat in a tiny witness box in a packed courtroom, plaintiffs would face aggressive white lawyers firing questions at them as white judges looked on. Fred Gray knew well that all their lives black people had been taught to defer to whites. Somehow these plaintiffs would have to find the steel to speak freely and the composure to think clearly while seated in a pressure chamber. And they would need to have a good story to tell.

The lawyers ruled out Rosa Parks. Her case was still being appealed, and they wanted the new federal lawsuit to be independent of any existing criminal case. Besides, Mrs. Parks had been arrested for disturbing the peace, not for breaking the segregation law. The MIA members proposed many candidates, and Gray interviewed the most promising. In the end, he whittled the list down to five names. All were women. This was because more women than men rode the buses, and because Gray and his colleagues wanted to protect the jobs of men, who were typically regarded as the breadwinners in families. All five women Gray selected had been bullied and insulted and cheated on buses, and all were still angry about it. It may have been a short list, but Gray thought it was a good one.

Ironically, the only one of the five who had previously appeared in court on a bus case was the youngest. But she had gone through the most. She had been tested by fire. Claudette Colvin had been on Fred Gray’s short list from the moment he conceived the suit. He picked up the phone and dialed a familiar King Hill number.

CLAUDETTE: When Fred Gray called our house in January, we were all surprised. The boycott was almost two months old, and I hadn’t heard from any of the leaders since it started, not even Rosa Parks. I was seven months pregnant. But we told him to come on out.

He arrived one evening with his secretary, Bernice. We sat around the coffee table in our living room, just as we had the year before, after I got arrested. He was still dressed in a dark suit and he still talked like a lawyer. Bernice still took dictation. The only change was my big belly. He described the case and discussed what would be expected of me if I took part. Because I was still a minor, he asked my parents if they would let me do it. Mom and Dad said yes.

Then he asked me. I was sitting on the piano stool. Bernice’s fingers moved whenever I spoke. He didn’t mention that there would be anyone else in the suit. I thought I was going to appear alone. As I listened, I was of two minds. In one mind I was afraid. The way life was in the South, how could you not be afraid? You never knew who was KKK, or who would target you. Every day on the radio, I’d hear angry white callers shouting that the Communists had invaded the black churches and people had to act now.

But I was not a person who lived in fear. My mom had always said, “If God is for you, the Devil can’t do you any harm,” and that’s how I felt, too. We all just lived that way. And I felt that if they really needed someone, I was the right person. It was a chance for me to speak out. I was still angry. I wanted white people to know that I wasn’t satisfied with segregation. Black people, too. And it didn’t sound like the trial would happen until after my baby was born. You had to do what you had to do. So I said yes.

“WE TALKED TO ALL THE FAMILY AT ONCE,” remembers Fred Gray, “and there was no reservation on anyone’s part. I wouldn’t have taken anyone with any reservation. I told them what would happen, what they would be subjected to. That there would be phone calls, there would be threats. I liked that family. They were self-sufficient. If there had been reprisals, they would have still gotten by. It took real courage to be a plaintiff in that suit. It wasn’t easy. And Claudette was the youngest.”

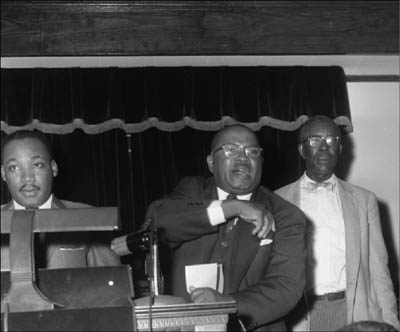

Claudette’s pastor, Rev. H. H. Johnson, makes a point at a mass meeting. Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. (left) and E. D. Nixon stand beside him

CLAUDETTE: After they left, my mom called our pastor, Reverend Johnson, and told him what Fred Gray had asked me to do. And my reverend came out to my home. Some of my neighbors were already afraid to talk to me. White Citizens Councils had formed to take jobs away from people who joined the boycott. I felt like no one wanted to be near me because I was so outspoken about ending segregation.

But Reverend Johnson really knew me and cared for me and stood by me. He worried about how I was going to hold up against those white people drilling me in court. He knew the terror was real. He knew what the stakes were. At my home he took my hands very gently and said to me, “Claudette, do you really feel up to it?” And once again I heard myself say, “Yes, Reverend Johnson, I do.”

My baby was born in Montgomery on March 29, 1956. I named him Raymond, after my uncle. Velma was with me in the hospital. Raymond came out very fairskinned with blond hair and blue eyes. At the hospital, the attendants kept bringing him in and asking me the name of his father. I wouldn’t tell them. They didn’t believe the father was black, and they held it against me. I would cover my head up because I didn’t want to hear the awful things they were saying about us. I didn’t need to hear that. I loved Raymond from the moment I saw him.

I only had about six weeks after Raymond’s birth to get ready for the boycott lawsuit. I wanted to get my body ready so I could fit into a good dress, and to get my mind ready, too. I rehearsed what I wanted to say. I prayed. My mother had always said, “If you can even talk to a white person without lowering your eyes you’re really doing something.” Well, I was determined to do that and more. Miss Nesbitt said, “Claudette, you always wanted to be in plays, to do Shakespeare. Now here is your stage.” And she was right: I had been speaking out against injustice since ninth grade.

At night, while I would lie in bed and rehearse the things I was going to say, Raymond slept beside me in a little bassinet. It was just the two of us in the front room, him breathing or fussing or pulling at his bottle, and me thinking about what I would say at the trial. Sometimes I thought about Harriet Tubman, about her courage. I prayed I could have her kind of courage on the trial day.

Or sometimes I would imagine, Claudette, you’re a Christian, and you’re about to get thrown to the lions and you have one speech to give to the Senate.

That was more like it. In my imagination that courtroom seemed like the Colosseum, and it felt like I had one last speech. I was going to make the most of it.