Is Montgomery to be a city in which bullets fly between sundown and sunup?

—From an editorial in the Montgomery Advertiser, January 1957

AS THE COURTROOM was being cleared of spectators, the three robed men went into Judge Johnson’s chambers, shut the door, and sat down. No one said anything for a while. Then Judge Rives said to Johnson, “Frank, you’re the junior judge here. You vote first. What do you think?”

Johnson replied, “Judge, as far as I’m concerned, state-imposed segregation on public facilities [the buses] violates the Constitution. I’m going to rule with the plaintiffs here.” Justice Rives quickly agreed. Justice Lynne didn’t. “The [Supreme] Court has already spoken on this issue in Plessy versus Ferguson,” he insisted. “It’s the law and we’re bound by it until it’s changed.” But Lynne was outnumbered. By a 2–1 decision a federal court abolished segregated seating on Montgomery’s—and Alabama’s—buses. As Judge Johnson later said, “The testimony of . . . Miss Colvin and the others reinforced the Constitution’s position that you can’t abridge the freedoms of the individual. The boycott case was a simple case of legal and human rights being denied.”

The decision, which took all of ten minutes to make, was announced on June 19, 1956. Shocked, Mayor Gayle declared that the city would appeal the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. But protesters rejoiced in a mass meeting at the Holt Street Baptist Church, a celebration tempered by the realization that they would have to keep walking at least until the city’s appeal reached Washington. The case probably wouldn’t be considered until fall. And there was no guarantee even then that the Supreme Court would agree with the Alabama judges.

WHAT THE JUDGES SAID

IN BROWDER v. GAYLE

Writing for the majority, Judges Johnson and Rives said:

We hold that the statutes and ordinances requiring segregation of the white and colored races on the motor buses of a common carrier of passengers in the city of Montgomery and its police jurisdictions . . . [violate] the due process and equal protection of the law . . . under the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the United States.

The “separate but equal” doctrine set forth by the Supreme Court in 1896 in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson can no longer be applied.

The day after the court’s announcement, Judge Johnson opened an envelope from the morning’s mail and unfolded an unsigned letter. It read:

If I had been in your shoes before I would have ruled [sic] as you did, I would rather have had my right arm cut off. I trust that you will get on your knees and pray to Almighty God to forgive you for the mistake that you have made.

It was just the first of many hate-filled letters and phone calls he would soon receive.

CLAUDETTE: I heard about the court decision on the news. Nobody called to tell me. By then I didn’t have much time for celebrating anyway. I had been kicked out of school and I had a three-month-old baby. My dream of being a lawyer was gone. I needed money so badly, and I was worn out trying to figure out how to get my life back.

When you’re a teenager and you first get pregnant, you can’t understand the reality of raising a child, especially if you don’t have the father to help out or even talk to you. I had no idea how much work there would be and how much money I would need. I didn’t have to pay rent to Mom and Dad, but I did have to pay for food and clothing and help with utility bills. My dad wasn’t working, and my mom made three dollars a day.

I hoped maybe some of the boycott leaders would understand my situation and help me, after what I had done. Deep inside I hoped maybe they would give me a baby shower. I needed money and support so badly. But I didn’t hear from any of them after I left the courthouse. Not Fred Gray. Not Rosa Parks. Not Jo Ann Robinson. No one called after I testified. I knew they couldn’t put me up onstage like the queen of the boycott, but after what I had done, why did they have to turn their backs on me?

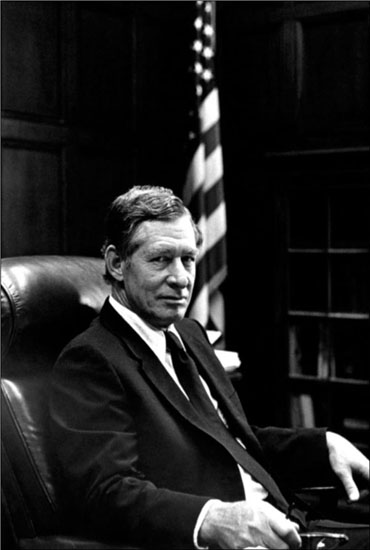

Judge Frank M. Johnson, Jr. “The strength of the Constitution,” he said, “lies in its flexibility”

I knew the answer: I was shunned because I had gotten pregnant. It was made worse because my parents wouldn’t let me just explain, “This is what happened and here’s who the father is.” Anyone could have understood, but I had promised my parents, so I kept it to myself. But because Raymond was light-skinned, and I wouldn’t name the father, they all assumed the father was white. Socially, I had three strikes against me: I was an unmarried teenager with a light-skinned baby. Without school, I had no circle of friends my age, and there was no way any of the women in town would accept me. To them I was a fallen woman.

But I wasn’t ashamed of myself. I knew I wasn’t a bad person. A more experienced and much older man took advantage of me when I was at my very lowest. I got caught up in a mistake, yes, but that’s all it was—a mistake. The people closest to me didn’t give up on me. They held on to me. Q.P. and Mary Ann loved me, and so did Mama Sweetie and Velma. They never forgot the good things about me. My pastor, Reverend Johnson, supported me. And Baby Tell, my mom’s best friend from Pine Level, was wonderful. Every second Sunday during my pregnancy I would go out in the country and stay with her. She would make the bed for me and read me to sleep from the Bible. She made a long little flannel gown for my baby, embroidered all the way around with the colors of the rainbow. And of course I had Raymond. He was a happy little fella. I was loved.

When the court decision came down, of course I felt joy for my people and pride for what I had done, but my day-to-day problems overwhelmed me. The thing that was constantly in the front of my mind was: How can I get started again? How in this world can I pick myself up?

THROUGHOUT THE SUMMER OF 1956, Montgomery’s mayor, councilors, and other officials tried everything they could to crush the boycott. They singled out Dr. King among the 115 blacks who had received indictments and went after him, accusing him of organizing an illegal boycott. The NAACP sent reinforcements from New York to help Fred Gray and other local attorneys defend Dr. King, but it was no use. Dr. King was found guilty by Judge Eugene Carter, the same judge who had ruled in Claudette’s appeal. Carter sentenced King to pay five hundred dollars and serve one year of hard labor in prison.

Reporters flocked to Montgomery from all over the world to report the dramatic racial showdown. Some frustrated whites complained that their leaders were all talk and that it was time to take matters into their own hands. If they didn’t act now, blacks would soon control the city. On the sweltering night of August 25, 1956, someone lit the fuse to several sticks of dynamite and lobbed them into the front yard of the Reverend Robert S. Graetz, the white pastor of Trinity Lutheran Church. The blast shattered the windows and rocked the walls of houses throughout the neighborhood. The Graetz family was spared only because they were away.

Summer and early fall brought more terror, more death threats, more hate mail and midnight phone calls—and frustration. Segregationists never seemed to run out of ideas or the money to carry them out. The White Citizens Council sought to pull insurance coverage from the MIA’s fleet of station wagons. City officials asked a state court to ban the car pool, claiming it was an unlicensed transportation system.

On Tuesday, November 13, Dr. King and other leaders sat in a courtroom, dejectedly listening to the city’s lawyers tell a clearly sympathetic judge that the boycott was illegal and should be outlawed. During a recess in the trial, Dr. King turned around and noticed Mayor Gayle, Commissioner Sellers, and two attorneys quickly disappearing into a back room. Several reporters hustled in and out of the same room. Something strange was going on.

Then one of the reporters walked up to King and handed him a news bulletin that had just come in. King read it and later wrote, “My heart began to throb with inexpressible joy.” The U.S. Supreme Court had just affirmed the lower court’s ruling in Browder v. Gayle. They had won! Word raced through the courtroom. One man rose and shouted, “God Almighty has spoken from Washington, D.C.!” Judge Carter banged his gavel for order. And then, in one last, utterly futile gesture, Carter ruled that the MIA car pool was illegal and must stop operating. It was all beside the point now. A team of creative lawyers and four tough women—two of them teenagers—had just booted Jim Crow off the buses.

GETTING TO SIT WHEREVER YOU WANTED

“I rode the bus with my aunt on the very first day,” recalls Annie Larkin, who was then sixteen. “We took the Highland Gardens bus that morning and I sat right up front. I had been following the boycott all the way through—I had only missed maybe five mass meetings in the whole year, so I wanted to ride on the very first day. I felt elated, I could sit anywhere I wanted.”

Gwendolyn Patton was fourteen when she moved from Detroit to Montgomery in 1960. She was well aware of the historic bus victory and proud to plop herself in a seat up front among white passengers whenever she rode the bus. But she found it puzzling that her grandmother still walked to the back to find her seat. One day Gwendolyn asked her about it. Her grandmother answered that she preferred to sit in the back. “Darling,” she explained, “the bus boycott was not about sitting next to white people. It was about sitting anywhere you please.”

Mayor Gayle vowed that the city would hold out until the very end, meaning until someone representing the United States actually showed up in Montgomery and delivered the Supreme Court’s order to integrate the buses. And now, because of Judge Carter’s ruling, the boycott was illegal. At a mass meeting, King announced that, until the Supreme Court’s order arrived, “we will continue to walk and share rides with friends.” He supposed it would take “three or four days.”

Five weeks later, on December 20—381 days after the boycott had started—two federal marshals arrived at the federal courthouse and served written notices on city officials that Montgomery’s buses had to be integrated. “I guess we’ll have to abide by it,” Mayor Gayle sighed, “because it’s the law.”

Many boycott participants would forever remember where they were when they heard the news. “I was cooking . . . when they made the announcement on the radio,” recalled Georgia Gilmore. “I ran outside and there was my neighbor and she said yes, and we were so happy. We . . . had accomplished something that no one ever thought would happen in the city of Montgomery. Being able to ride the bus and sit anyplace that you desire.”

At 5:55 the next morning, Dr. King and four other leaders, none of whom were plaintiffs in Browder v. Gayle, stepped aboard the open door to an empty bus at a stop near King’s home and dropped coins into the fare box. When the white bus driver recognized the famous man coming through the door, he smiled and said, “I believe you are Reverend King, aren’t you?”

“Yes, I am,” King answered.

“We are glad to have you this morning,” said the driver.

December 21, 1956, the first day of integrated bus service in Montgomery: (front) Rev. Ralph Abernathy and Inez Baskin of the Montgomery Advertiser; (back) Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Rev. Glenn Smiley

With that, the bus protest ignited by Claudette’s arrest twenty-one months earlier came to an end. It was one of the great human rights victories in U.S. history. But many years later one writer noticed something peculiar about that first bus ride. “It is interesting,” puzzled Frank Sikora in his book The Judge, “that Claudette Colvin was not in the group.”

Browder v. Gayle may have ended legal segregation on the buses, but it did not end racial prejudice. Less than a week after the buses were integrated, five white men jumped out of a car at a Montgomery bus stop and surrounded a fifteen-year-old black girl. Cursing her, they beat her to the ground and sped away. Four days later a second young black woman, named Rosa Jordan, was shot in both legs while riding the Boylston bus by a sniper whose bullets penetrated the vehicle. Around the same time, Aurelia Browder’s daughter Manervia ran to answer the phone ringing late in the night. “Your house is gonna be blowed sky high!” a voice said. She became hysterical. Her mother grabbed the phone and told the caller, “Blow it up. I need a new house, anyway!” and slammed the phone down.

A demolitions expert carefully defuses a bomb in the tense aftermath of Browder v. Gayle

Violence and threats of revenge were everywhere in the first days of integrated buses. Annie Larkin remembers being in a mass meeting at a church soon after the Supreme Court’s decision. “We had gotten there at four p.m. to get a good seat. But while the meeting was going on people came and set fire to the cars parked out in front of the church. No one would let us out until it was safe. A guard unit ended up escorting us home about four a.m.”

Montgomery turned into a battle zone on the night of January 10, 1957, as bombs rocked the city’s black churches. Claudette’s church, Hutchinson Street Baptist, was dynamited, its stained-glass windows blown to pieces. The Bell Street Baptist Church was bombed, too, as was Reverend Abernathy’s home. Terrorists once again bombed the home of Reverend Graetz—especially despised by many as a white clergyman who openly supported black rights. All in all, four churches and two houses were damaged by explosives that night. Another bomb tossed onto Dr. King’s front yard somehow failed to go off.

It was clear that anyone connected to the boycott, anyone whose name or picture had been in the paper—was now in grave danger. Q. P. Colvin, planted in his chair on King Hill, stayed close to his shotgun. The Montgomery Advertiser summed up the first days of 1957 with a blunt editorial: “The issue now has passed beyond segregation. The issue now is whether it is safe to live in Montgomery, Alabama.”

CLAUDETTE: I was afraid, but I couldn’t just hide at home. I had to work. I needed money. I decided I would be safer in restaurants than in white people’s homes—you never knew who was KKK. But whenever I’d start a job in a cafeteria, word would get around fast about who I was. Sometimes black people would recognize me and come up and embrace me and say, “You the girl!” I got fired from several restaurant jobs when my employers found out I was the one who wouldn’t give up her seat. I’d change my name back and forth from Colvin to Austin so I could work, but they’d always find out and that was that. It was hard for me to remain anonymous.

No one with any pull would help me or hire me. Those were hard, fearsome days: In those days, it seemed like I couldn’t go anywhere and no one wanted to be near me. I wanted to escape from there.

There was one small good thing that happened right after the boycott ended. One afternoon Reverend Ralph Abernathy, the pastor of the First Baptist Church, called our house and invited me to a private reception there. Abernathy knew Velma because she was a member. I decided to go. There weren’t very many people invited, just a few from ASC, and a reporter, and Velma and I, and the Kings and Abernathys.

Dr. King sat near the door, always surrounded by people. Reverend Abernathy stayed close to him. After a while, I got up and went in the kitchen to help Mrs. Abernathy serve ice cream. I carried a scoop out to Dr. King, still sitting by the door. I had never met him before except to shake his hand in line after a mass meeting. I had always been too shy to approach him. Usually there were too many people around him to get near anyway.

When he saw me, he stood and introduced himself and thanked me for being in the court case. He said, “You’re a brave young lady.” I told him I was trying to get back to school, and he listened with interest. It wasn’t a long conversation; I moved on quickly. But it was important to me. How could you not respect him? King put his life on the line and didn’t have to. Because he stood up, his life was always in danger, more so than the other ministers’. His speeches at the mass meetings kept people walking and kept things from getting out of control.

Meeting Dr. King didn’t pay my bills or stop people from gossiping about me and Raymond. It sure didn’t make me any safer. But I have to say those few words of praise from him on that evening felt very good.

Claudette Colvin, February 2005, speaking to students at Booker T. Washington Magnet High School