4

Fighting and Dying for the Union

Indiana in 1860 presented a significantly different political landscape than had been the case ten years earlier. In 1850 the Democrats had been consolidating gains made at the expense of the disintegrating Whig Party. The Republican Party was now on the verge of scoring similar victories over a tired and split Democrat Party. Indiana Whigs had finally accepted the Republican ascendancy; and in an attempt to keep them in line, the former People’s Party candidate for governor, Oliver Morton, suggested downplaying the slavery issue and nominating former Whig Henry Lane for governor. The payoff for Morton was that if Republicans won both houses of the legislature, Lane would immediately be elected U.S. Senator, and Morton would walk into the governor’s office without a fight.1 The deal worked, but the attempt to downplay the slavery issue did not. Debates over slavery ignited all over the state.

Each party tried to portray the other as “Negro loving.” The Democrats said the Republicans preferred African Americans to white foreigners and were prepared to import hordes of free blacks into Indiana to compete with white labor. The Republicans claimed that it was the Democrats who would spread slavery to the territories and thus prevent the children of Hoosiers from seeking their fortunes in the West. The fact was that neither party favored equality for African Americans. Candidates fought over fine gradations of how the Fugitive Slave Act should be enforced, for example. Hoosier delegates to the Republican National Convention favored Abraham Lincoln over William Seward, the former New York governor and U.S. Senator, because they thought Lincoln was less of an antislavery candidate than Seward.

One of the key constituencies to be fought for was the immigrant vote. As stated earlier, the foreign-born population of Indiana had more than doubled in ten years. Most of these were Irish and Germans who were traditionally Democrats. The Republican Party sent German-speaking campaigners, including Carl Schurz, John Popp, and Charles Coulon, into Indiana and published thousands of election flyers in German. In the end, these efforts were heralded by newspapers as contributing heavily to Lincoln’s narrow victory in Indiana. It was not until 1967, when Thomas Kelso took the time to analyze actual election returns from nine Indiana counties with German-dominated townships, that historians were finally able to say with finality: “Traditional theses about a Republican voting pattern among Germans is not supported by data from Indiana.”2 Kelso determined that the “Germans did not overlook those aspects within the new party which were presumed to be anti-immigrant,”3 including: the Republican Party’s Know-Nothing roots, a temperance element within the party that was anathema to Germans, and the party’s image as being more problack equality than for equal rights for immigrants.4 Kelso traced the erroneous assumption of a “glorious German contribution to Lincoln’s victory,” to books written at the beginning of the twentieth century by German historians Julius Goebbel (1904), Georg Von Bosse (1908), and A. B. Faust (1909).5

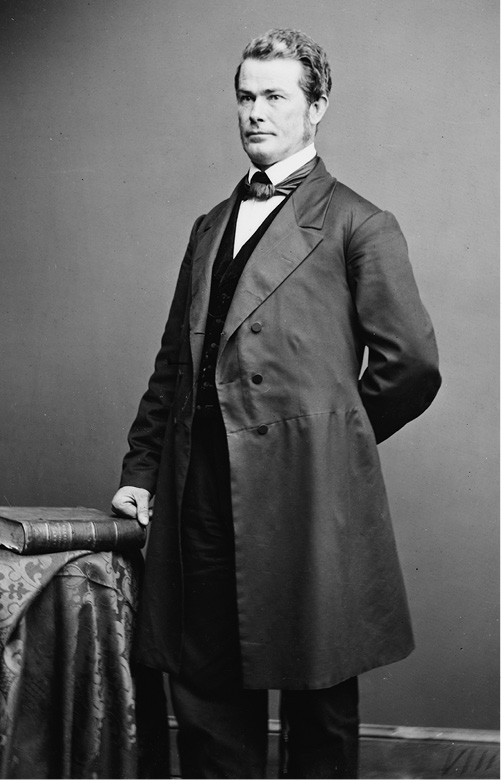

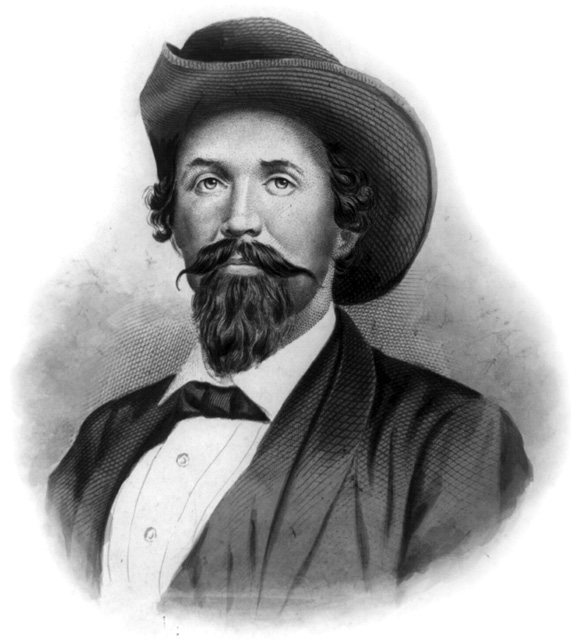

In the race for Indiana governor, Lane defeated former congressman Thomas Hendricks by nearly 10,000 votes.6 Scott County went for Hendricks, as did Clark County, while Jefferson County held true to its past and favored Lane by more than 800 votes.7 A new face won the second congressional district seat. Democrat James A. Cravens of Washington County defeated Republican John Davies by a narrow margin of 539 votes.8 Cravens lost Floyd and Perry Counties along the Ohio River, but he took both Scott and Clark Counties. Cravens played a prominent role in Civil War politics in southern Indiana as he tried to ride the fence between his Union and Copperhead constituents.

A veteran of the Mexican-American war, James A. Cravens of Indiana served in Congress from 1861 to 1865. He died in Hardinsburg, Indiana, on June 20, 1893. (Library of Congress)

The year 1861 arrived with one state, South Carolina, already seceded from the Union. While Democrats had warned during the past campaign that a Republican victory would bring about Civil War, both parties tried to find ways to preserve the Union in the winter of 1861. Union meetings were held across the state with members of both parties attending. The Madison Courier called for a joint meeting of the Kentucky and Indiana legislatures to try to mitigate the crisis. Compromise, generally in the form of stricter adherence to the Fugitive Slave Act for the sake of Union, was promoted particularly in southern Indiana, where ties to the South were closest. Rallies and county conventions were held in virtually every Ohio River county, and many, such as Perry County, declared that its true interests lay with the South. Economic and kinship ties made the sentiments, and even loyalty, of many southern Hoosiers suspect throughout the war to come.

Demagogues and Disunion

The most bizarre Civil War-era drama involving southern Indiana politicians was the ouster of Jesse Bright from the U.S. Senate. Bright was a resident of Madison, a confidant of William English, and a backer of John C. Breckinridge over Stephen Douglas for the 1860 Democratic presidential nomination. Bright had earlier served as a member of the Common Council (First Ward) of Madison, as a state senator from 1841 to 1843, and as lieutenant governor from 1843 to 1845 before his election to the U.S. Senate by the general assembly in 1845.9 It was his support of Breckinridge that got him in trouble with his own state party. The Democrats rejected Bright’s chosen slate of candidates in the 1860 state convention10 and went with a broader Douglas slate. Even in Indiana, where Bright and English were prominent supporters of Breckinridge, local Democrats shifted to Douglas.11 Breckenridge received only 12,300 votes in Indiana, compared to 115,500 for Douglas.12

Bright’s correspondence with Jefferson Davis during the secession crisis fatally damaged his relationships in the Senate. Bright addressed a letter, dated March 1, 1861, to “Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States,” and suggested to his old friend the name of an arms dealer who offered fair prices. When the Senate erupted in protest at Bright’s implicit recognition of the Confederacy, Bright wrote to English, “There is some talk, I understand, of their expelling me on account of my known disloyalty. Let it come, I have got so that I believe nothing I read and am not surprised at anything that takes place.”13 Bright is the last U.S. Senator in history to be expelled from that body. After his expulsion in February 1862, Bright moved to Kentucky, served two terms in the legislature there from 1867 to 1871, and died in 1875.

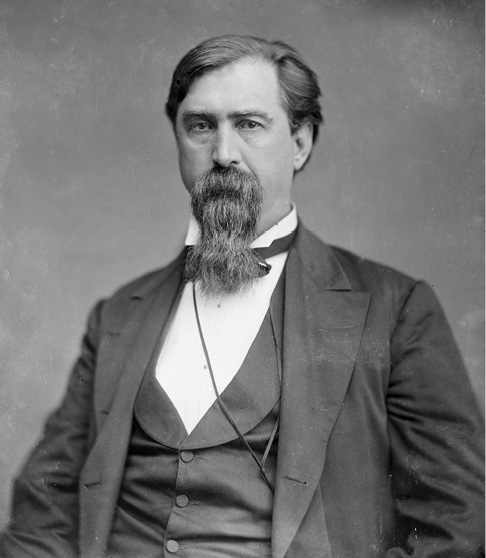

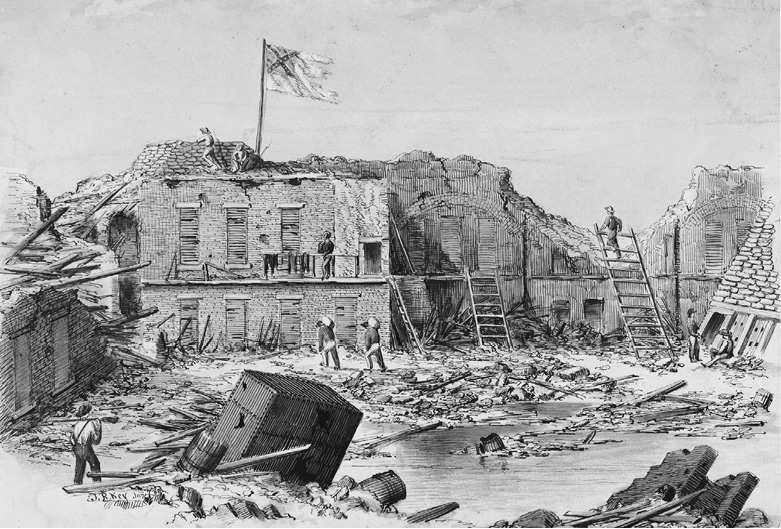

Equally resistant to compromise was the new Indiana governor, Morton, who traveled to Washington, D.C., in March 1861 to offer Lincoln 6,000 Hoosier troops to help in putting down the imminent rebellion. In a speech celebrating Lincoln’s victory, Morton had said, “If it was worth a bloody struggle to form the nation, it is worth one to preserve it.”14 Even before the shelling of Fort Sumter, some prominent Democrats began to move away from mainstream Hoosier thinking. While most citizens were still struggling with their feelings about the Confederacy, Congressman Daniel Voorhees, elected in 1860 and known as the Tall Sycamore of the Wabash, acted as an early counterpoint to Morton. At a meeting in Greencastle on April 10, 1861, Voorhees blasted away at talk of calling up troops. “Not one dollar and not one man from Indiana with which to subjugate the South and inaugurate Civil War,” he said.15 Voorhees did not have to worry about an invasion by the North. Two days later, Fort Sumter, commanded by Hoosier major Robert Anderson, was shelled into submission. And the Civil War was on.

U.S. Senator Daniel Voorhees of Terre Haute, Indiana (Library of Congress)

Voorhees became one of the prominent national leaders of the “Peace Democrat” movement. Along with Clement Vallandigham of Ohio and others, Voorhees tried throughout the war to maneuver Union military and political commanders, including Lincoln, to the negotiating table. Voorhees believed that Lincoln had no right to use force to preserve the Union, and that only economic self-interest could entice the South back into the fold.

At least one of Voorhees’s Democratic colleagues was willing to go further. Second district Congressman James Cravens, in a letter to English dated three days before the fall of Fort Sumter, proposed that the southern portions of Indiana, Ohio, and Illinois be separated into a new state called Jackson and that this new state would secede.16 “I cannot obliviate [sic] the fact that our interest is with the South and I cannot reconcile the separation, and it will be the last day in the evening before I consent to fight them,” wrote Cravens.17

A Confederate flag flies over the ruins of Fort Sumter. Although rebels occupied the fort, they withstood an almost constant bombardment by federal forces from July 1863 to February 1865. (Library of Congress)

According to historian Emma Lou Thornbrough, “Sumter had an electrifying effect on Indiana.”18 Morton raised 12,000 troops within two weeks.19 Heretofore “compromise” newspapers such as the New Albany Ledger and the Indianapolis Sentinel pledged support for the war. The Sentinel’s editor, J. J. Bingham, had a slight nudge along the path. Shortly after Sumter, a mob arrived at his home and forced him to go the mayor’s office to swear loyalty to the Union.20 The Indiana General Assembly became symbolic of the debate statewide. Republicans tried to corner the market on loyalty, embittering the Democrats who went out of their way to prove their patriotism. State Senator Smith Jones of Bartholomew County, in a letter to his friend Allen Hamilton, said, “There are no traitors in Indiana.”21

Still, speeches such as that of State Representative Horace Heffren gave the suspicious plenty to talk about. During the 1861 legislative session, Heffren, who represented Washington and Harrison Counties, said he would “gladly bear the epithet ‘traitor’” because he sympathized with the South. Heffren claimed more than 100,000 Hoosiers stood ready to prevent any Indiana army “under abolition banners” from crossing the Ohio River. When asked if he would fight against the Union, he said, “I will leave my native land, my hearthstone, my wife and family and become a private in the southern army, rather than be the commander-in-chief of an abolition army.”22 Heffren later did a flip-flop, accepting a commission as a lieutenant colonel in the Fiftieth Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment, and then resigning his commission to join the Sons of Liberty (an anti-Morton group whose membership and mission are murky, at best).23

Defeat, Draft, and Emancipation

With southern Indiana politicians fanning the flames, 1862 did not promise to be a good year for the Union cause in Indiana. Benjamin Kimberlin sounded hopeful in a letter to his brother, Jacob R., while in reserve before Corinth, Mississippi. Benjamin wrote:

the other great battle that has long been expected here has not come off yet, but we are almost expecting it to commence every day our pickets and the rebel pickets has a skirmish nearly every day and I think there cant be many days before a general engagement will take place for our army is advancing on Corinth slowly. Jake I don’t know how it looks to you but I think the Secesh is nearly played out and if we whip them here it will bring the war nearly to a close. … let me know how all of your crop looks and how you are getting along generally particularly among the girls. As to the crop part I expect you are doing very well, for you wrote that you had a good plough team and was going to ploughing in a few days for corn, Jake I don’t mean that you can get along better with a crop than you can with the girls for I think you are the boy that can get along very well with boath, not using any flattery or anything of the kind.24

Despite Benjamin’s optimistic outlook, General George McClellan’s failure to secure the Virginia Peninsula, Union defeat at Second Bull Run and in the Shenandoah Valley, and indecisive battles at Shiloh, Fair Oaks, and Antietam left Hoosiers doubting more than ever the wisdom of prolonging the war.

In June 1862 Congress authorized the states to implement a draft to meet their troop quota.25 An enrollment officer was named for each county, with a deputy in each precinct. Any white male age eighteen to forty-five was eligible. The draft convinced thousands more Hoosiers, including a second wave of Kimberlins, to volunteer so they could choose their regiment. Between July 31 and August 11, a Lieutenant Campbell enrolled ten more members of the Kimberlin clan at Lexington. All ten signed up for Company K, Sixty-Sixth Indiana Volunteers.26 The entire Sixty-Sixth Indiana came from the second congressional district.27 Like the Kimberlins in the Twenty-Third Indiana, the volunteers were treated to the sight of a prominent general when they arrived at Camp Noble to muster in. General Lew Wallace, former commander of the Twenty-Third, swore them in and gave them a pep talk.28

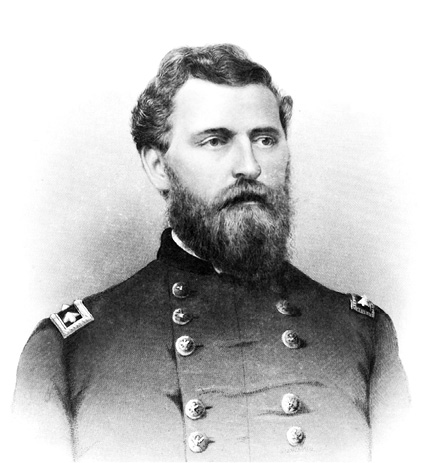

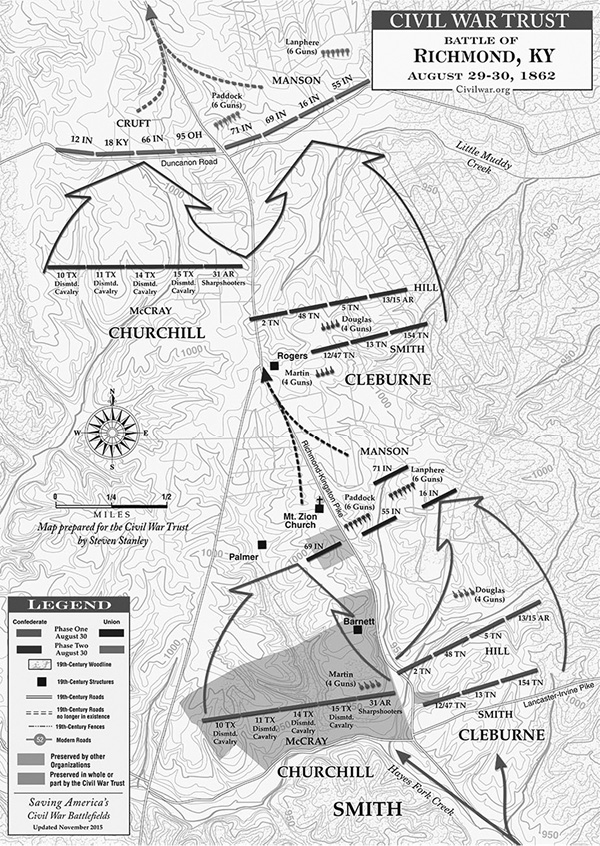

Daniel Kimberlin, at age thirty, was the oldest of the tight-knit group that became soldiers together on August 19, 1862. The five foot, nine inch grey-eyed redhead left for Lexington, Kentucky, the same day. Colonel Roger Martin planned to train the Sixty-Sixth at Camp Nelson near Nicholasville, but when they arrived, there was no time to play war. Confederate general Kirby Smith was reported moving north toward Richmond, Kentucky. On August 23 General William “Bull” Nelson sent the Sixty-Sixth forty miles southeast of Lexington to the foot of Big Hill. There, on August 30, just south of Richmond, 6,500 Union soldiers under General Charles Cruft faced 16,000 Rebels.29

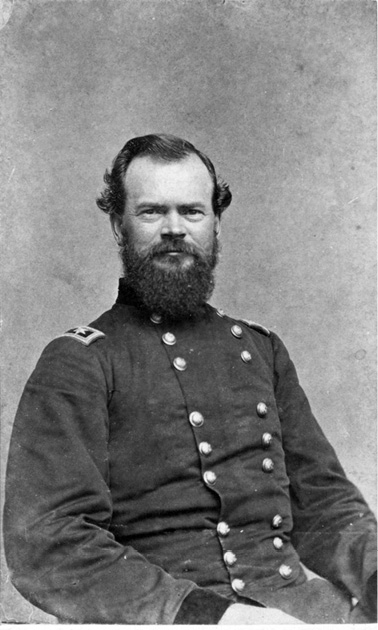

General Charles Cruft of Terre Haute, Indiana (Library of Congress)

The battle consisted of three phases. During phase one, Manson’s brigade took the brunt of General Patrick Cleburne’s Rebel advance up the Richmond Road (US 421). While the Sixty-Sixth Indiana was held in reserve as part of Cruft’s brigade, Manson mistook Rebel skirmishers for the main Confederate advance and shifted his command east to counter it. Confederate general Thomas Churchill then brought his brigade through a draw to the west and outflanked Manson’s right, forcing an orderly Union retreat.30 Nelson ordered Cruft’s brigade, including the Sixty-Sixth, forward to Rogersville, where they set up a rallying point for Manson’s command and established a defensive line across the Richmond Road. The Sixty-Sixth tried three times to stop Rebel advances during a day when temperatures reached 100 degrees. They constantly fought and retreated, once making a desperate lunge across a hayfield at the Fourteenth and Tenth Texas Regiments at midday.31

The Sixty-Sixth made its last stand along the south iron fence of the Richmond Cemetery, and then covered the general Union retreat through the center of Richmond.32 At the end of the day, the Sixty-Sixth was overwhelmed, and all of its members were either killed, wounded, or captured. While not an official surrender, the practical effect was that for nearly a year the unit was lost to the Union service.33 Confederate casualties were 78 killed and 372 wounded. Union losses were 2,000 taken prisoner, 844 wounded, and 206 killed.34 Daniel was one of those who perished. He had been a soldier for just eleven days. The other nine Kimberlins and Whitlach cousins were paroled and spent the early fall in a parole camp in Indianapolis until they were released in the late fall. All nine rejoined their unit. The Kimberlin who had been designated a year earlier to stay behind on the farm finally volunteered when the draft began. Twenty-year-old Jacob “R.,” the boy who had been the recipient of most of the letters from the battlefield to date, joined the Fifty-Fourth Indiana for a three-month stint. Jacob wrote to old Isaac Jones Kimberlin from Russellville, Kentucky, on July 30, 1862: “It seems like I aught to be at home at work but if no bad luck should happen it wont be very long until I will … if that corn is not plowed at Henrys just let it a lone”35

Map depicting the movement of Union and Confederate armies at the Battle of Richmond in Kentucky, August 29–30, 1862. (Courtesy Civil War Trust)

Old Isaac replied on August 22 with all the news from Lexington:

The war Spirit runs high here a great number has lately volenteerd I will name some of them to wit Abraham Kimberlin, John S. Whitlatch, Reace and Alexander Whitlach, John, James and Daniel Varble, Daniel Kimberlin [he died at Richmond eight days later] William Hough and a great number about Lexington all went in the 66th Regt of Ind Vol there now somewhere in Ky… by what I see in the papers the rebels is deturmind to try Ky and Tenn again but I hope the good Lord will disappoint them in their wickedness … your affectionate Father even till Death.36

The dutiful son wrote from Bowling, Kentucky, on September 4, that he had made the right choice: “If I had staid at home I would been in the three years service now … I know you have a pretty hard time but take as good care of the things as you can a few days longer and I think I will be there.”37

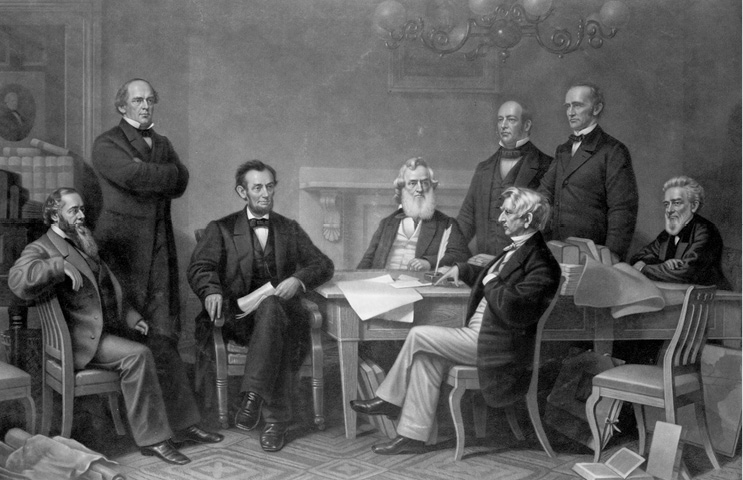

The most wrenching events of 1862 did not take place on the battlefield. Lincoln’s dual announcements in September of his Emancipation Proclamation and the suspension of habeas corpus for those charged with disloyal acts38 did more to stir up emotions in Indiana than any military defeat could have accomplished. The Democratic Indianapolis Sentinel editorialized that the Proclamation was “a blunder fraught with evil.”39 From the Proclamation forward, the justification for the war changed from preserving the Union to freeing the slaves. The Democratic slogan “The Constitution as it is, the Union as it was” was directly challenged.40 War Democrats who had been known for being willing to fight to preserve the Union fled the Union Party that Morton had tried to hold together. Any sense of unity disappeared as the last thread connecting pro-Union Democrats and pro-Union Republicans wore through. It became more difficult for many Hoosiers to fight for what they now perceived as a war for African Americans.

President Abraham Lincoln reads the Emancipation Proclamation to his cabinet. From left to right: Edwin M. Stanton, Secretary of War; Salmon P. Chase, Secretary of the Treasury; Lincoln; Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy; Caleb B. Smith, Secretary of the Interior; William H. Seward, Secretary of State; Montgomery Blair, Postmaster General; and Edward Bates, Attorney General. (Library of Congress)

Secret Societies

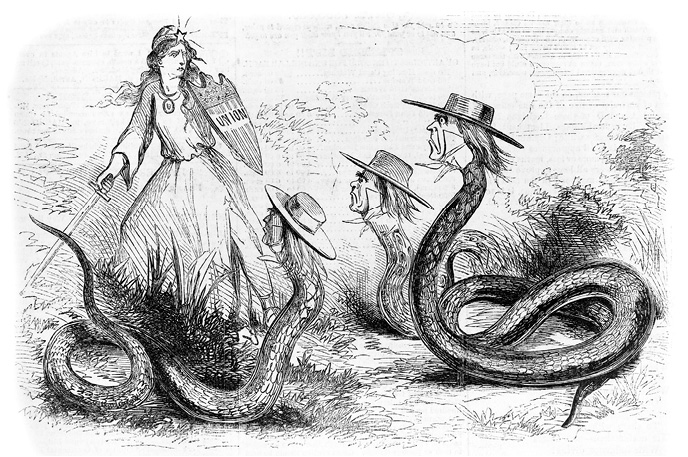

Morton recognized the danger to himself and the Union Party cause if the Copperheads were left unrestrained. He seized on careless statements by his political rivals Hendricks of Madison, Voorhees from Terre Haute; and Vallandigham of Ohio who all hinted at the possibility of a great “Northwest Confederacy,” which would be separate from but allied with the South.

Morton used the Indianapolis Journal to proclaim the existence of “secret societies” whose mission was to subvert civil government in Indiana and to establish the Northwest Confederacy. A federal grand jury of fourteen Republicans actually investigated and indicted forty-seven Hoosiers in August 1862 on counts of treason and conspiracy. The Journal said on August 4 that “so gigantic a conspiracy is second only to the rebellion of which it is an offshoot.”41 No trials were held, but the indictments served Morton’s purpose. Speculation about the existence of secret societies permeated public debates and affected public policy, individual careers, and personal lives throughout the war.

Historians disagree on whether the secret societies existed, and if so to what extent. In 1918 Indiana historian Mayo Fesler published the first attempt to document the existence of three groups that he claimed were formed independently, but had similar goals and some duplicative membership. According to Fesler, the Knights of the Golden Circle was formed in 1853 by Doctor George Bickley, a Cincinnati surgeon, in order to promote the colonization of Mexico.42 The KGC evolved into an anti-Union society after its first convention in Raleigh, North Carolina, in 1860, and, according to Orange County, Indiana, tradition was brought to the Hoosier State by William Bowles, a Scott County native who settled in Paoli.43 In an undated letter to his wife, Bowles wrote: “If Ky had gone out at the proper time, southern Ind. Would have been with her today, if not the whole state.”44 Bowles may have been accurate in his assessment. His hometown newspaper, the Paoli Eagle, said that “in case of dissolution, Indiana’s interest points to the South as the natural place for her to go.”45 The citizens of Perry County along the Ohio River voted in 1861 that if war should come, the dividing line should run not along the Ohio River, but north of the Perry County line.46

A February 28, 1863, editorial cartoon shows three caricatured Copperheads advancing on Columbia, who holds a shield labeled ”Union” and a sword. (Library of Congress)

The wave of arrests that followed the suspension of habeas corpus, and General Ambrose Burnside’s (a native of Liberty, Indiana) General Order Number 38 in April 1863, suppressed KGC activity to the point where it ceased to exist as an organization. General Order Number 38 said that anyone who “declared sympathy” for the enemy would be subject to military justice.47

A second group, the Order of the American Knights (founded in Missouri in 1863), according to Fesler, absorbed the mission of the KGC, but was never very strong in Indiana. The third organization, the Sons of Liberty, Fesler said, formed in Indiana in 1864 with Harrison Dodd, publisher of the Indianapolis City Directory, as state commander.48 Fesler cited as evidence for the existence of these secret societies a series of incidents, some violent, that occurred across Indiana. These included the murder of a soldier on leave in French Lick, the murder of a grand jury witness in Morgan County, a shootout between KGC members and former legislator Louis Prosser in Brown County, and the organization and drilling of armed bands in Nashville’s town square.49

Federal agents raided Voorhees’s Terre Haute office in August 1863 and confiscated KGC literature and letters from former U.S. Senator James Walter Wall of New Jersey that told of the availability of 30,000 Garibaldi rifles.50 A month earlier, in New Albany, agents arrested George Bickley, the KGC founder, as he tried to sneak the group’s literature into Indiana.51

Fesler estimated the Indiana membership of the KGC to be 125,000, while the SOL membership was around 50,000.52 The Indianapolis office of SOL Grand Commander Dodd was raided by a federal provost marshal looking for smuggled weapons. Discovered in the office were more than 350 navy revolvers and 135,000 rounds of ammunition.53 The ultimate proof, according to Fesler, may have been the Battle of Pogue’s Run in Indianapolis, on May 20, 1863. Fesler said that 3,000 armed “radicals” used the cover of a Democratic Party rally to plot the seizure of Camp Morton, a large prisoner of war camp, near present-day Twenty-Second Street and Central Avenue. Federal troops disrupted the rally and afterward stopped trains leaving town. According to Fesler, they confiscated about 500 guns.54

Writing in 1960, Frank Klement said the secret societies were “a political apparition. … It was a figment of Republican imagination … a contribution to American mythology.”55 In a sequel to his first work, Klement said the KGC was based, in part, on lies composed by Colonel Henry Carrington.56 Carrington was a friend of Morton who owed his position as commander of the District of Indiana to Morton’s intercession with General Burnside. According to Klement, Carrington “concocted an assortment of cock-and-bull stories, and related them to Burnside with a straight face”57 Klement said that no lists of paid KGC or SOL membership were ever found and not a single chapter or “castle” existed in Indiana. Klement said Fesler did not turn up a single old-timer who admitted belonging to a secret society.58

A third historian, Lorna Lutes Sylvester, takes a position between Fesler and Klement. Sylvester said “claims by recent historians that Morton fabricated the entire KGC legend are questionable. To believe that endows Morton with an omnipotence that his most ardent admirers did not claim for him.”59 If, as some historians claimed, most Democrats supported the war and only condemned Morton, then “they suddenly failed to attend their local party meetings in the spring of 1863.”60 Ultimately, Sylvester said, “Historians must still base their conclusions on partisan newspaper accounts, political propaganda, and speeches and correspondence written during turbulent times.”61

Current scholarship has undermined Klement’s claims that secret societies were the figment of the imaginations of Northern politicians and Union army officers, and have called into question the historian’s research methods and findings. A 2015 study by historian Stephen E. Towne examined the intensive U.S. Army intelligence operations in the Midwest during the war and its efforts to uncover subversive organizations and activities. Towne noted that based on the reliable evidence uncovered by investigators, “upheaval and violence were close to the surface throughout the region as ideologically driven secret political groups threatened large-scale unrest.”62

Whether the KGC, the OAK, and the SOL were extensive underground organizations, or simply the reflection of intense resentment on the part of southern Indiana citizens toward the imposition of Republican political goals, the result was the same. Southern Indiana was a cauldron of boiling emotion that often spilled over into violence. Families were split, towns divided, and reputations smeared.

While Morton was able to keep the Copperheads off balance with the specter of the secret societies, he was not initially able to turn his strategy into electoral success for his new Union Party. The Democrats swept the fall 1862 elections, taking seven of nine statewide races and seven of eleven congressional seats, along with both houses of the legislature. Scott County voters continued their recent habit of sending Democrats to the general assembly and to Congress. Copperhead politicians such as Cravens, the Kimberlins’ congressman (the second district included Clark, Crawford, Floyd, Harrison, Orange, Perry, Scott, and Washington Counties) took full advantage. Cravens beat the Republican James G. May 10,911 to 6,211. In Scott County, Cravens won 800 to 562 votes.63 The Union Party was now seriously wounded.

The Democratic sweep in the fall 1862 elections spelled more trouble for Morton. The Democrats used their new power in the legislature to embarrass the governor and to chide Lincoln for a failed strategy. Peace Democrats introduced several resolutions, professing that peace could never be accomplished by the sword. Others urged compromise and a unilateral armistice. The final report from the Senate Committee on Federal Relations bitterly criticized Lincoln and Emancipation, but also condemned secession.64

The 1863 legislative session ended with a Republican walkout over the Democrats’ attempt to divide authority for the militia between the governor and other state elected officials. Morton called it an act of treason.65 But the low point for Morton and the Republican Party came a few months later on July 1, coincidentally the opening day of the Battle of Gettysburg. The Democratic State Auditor, Joseph Ristine, refused to pay bills because the session ended without the passage of the appropriation legislation. When Morton appealed to the Indiana Supreme Court for help, the court rebuffed him. What followed was a constitutional and political standoff that almost resulted in violence. Morton, with his personal guarantee, immediately borrowed money from New York banks, appealed to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to take up some of the state’s military expenses, and asked friends such as Calvin Fletcher and Republican county officials to make personal contributions. In the meantime, General John Coburn was in Indianapolis with a regiment of troops. Coburn offered to break into the state treasury to confiscate the necessary funds. Morton declined Coburn’s offer and maintained the borrowing strategy for two years, keeping the state’s cash in a safe in his office.66 Morton’s bold move led Democrats to compare him to Charles I of England who defied Parliament and personally financed the government of England for eleven years, from 1629 to 1640. Charles later paid for his audacity with his head.67

Morton kept his head, and his extraconstitutional tactics kept the war economy running, but he was not able to win over the hearts of Hoosiers living south of the National Road. Copperhead rejection of the shifting justification for the war sparked an intense backlash, which evolved into violence across southern Indiana. The Madison Daily and Evening Courier reported on February 24, 1863, that a “grand pow-wow was held at the courthouse in Lexington … the old brick walls rang for an hour with the stentorian voice of Hon. William H. English. He said the war was an abolitionist war waged expressly for the extermination of slavery, and it must be stopped.”68

The young diarist of Lexington, Sarah Waldschmidt Young Bovard, continued to observe events in her little world. She got her war news from the Cincinnati Gazette. Local reaction occurred daily: “The Butternuts are getting very saucy in Indiana,” she wrote,69 just two weeks after Congress passed a federal draft bill. One month later Bovard recounted, “The Butternuts had a meeting last night at the Franklin school house and Isaac Mayfield had a Union one at the McClain school.”70 A week later, “two Union men were killed in a riot and rebel mobs in Brown County.”71 In October she noted, “The Copperheads meet in the woods up at Cat Wallow. M. Eyfelds tried to kill an abolitionist.”72 On Thanksgiving Day 1863, the ultimate sign of a split in Bovard’s family over the war: “Mother roasted a turkey for Margaret. Don’t want anybody but secesh to help eat it.”73

James Adams of Brookville served as a colonel in the Forty-Fifth Indiana. He wrote often to his sister, Catherine Allison, who had a Copperhead husband, J. D. Each time Catherine received a letter from James, her husband became enraged and confiscated the letter. On May 17, 1864, James wrote to Catherine: “I have thought considerable about your situation … I will give you a plan. I will place that which is strictly private on one sheet, and what he may see on another. You can secret the one and hand him the other.”74 Before the war was over, Catherine had divorced J. D.

In the summer of 1863, when the federal draft began, correspondence between Doctor John McPheeters, assistant surgeon in the Twenty-Third Indiana (one of the Kimberlin regiments) and his wife, Mollie, turned to the draft. Mollie wrote on June 15: “some of the copperheads talk more boldly. A great many in Stamper’s Creek Township say they will shoot the man who comes to enroll their names. Port Cornwell was appointed enroller, but declined the appointment.”75 Two weeks later, George McPheeters, John’s brother, wrote: “There seems to be a determination in a number of localities to resist the conscript. Extensive organizations for that purpose. A few enrolling officers have been shot. The enrollment has been stopped by armed force in a great many places.”76

In an undated letter to Governor Morton, Doctor James Hosea of Scott County described a Copperhead meeting at the Austin schoolhouse, eight miles northwest of Lexington in Scott County, where fifty-four men gathered. The chairman was a Mr. Sirrup. According to Hosea, the men pledged not to help out any families whose sons have gone to fight, and to protect deserters.77

The hysterical suspicion was mutual. Kenneth Stampp wrote that “loyal citizens lived in panicky fear of their own neighbors, and lumped all dissidents into the single category of traitors.”78 Violence and intimidation suppressed logical debate. Reminiscing seventy years after the war, Julie LeClerc of Vevay noted that “the little town of Veevay [sic] was divided between Unionists and southern sympathizers. When Jason Brown, state representative from Dearborn County, came to speak in support of Vallandigham, the Ohio Peace Democrat, the Unionists element rushed into the LeClerc house, and threatened to swing him from the nearest lamp post.”79

A similar story involved the annual July 4 celebration on the Lexington town square. Interviewed in the Scott County Journal in 1924, Alice Jones recalled “the 1863 celebration was disrupted by Copperheads shouting hooray for Jefferson Davis. One was attacked by an elderly lady with a parasol.”80 That was the day after Gettysburg and Vicksburg fell, and it was three days before Confederate General John Hunt Morgan crossed into Indiana.

Morgan’s Raid

When Morgan crossed the Ohio River at Brandenburg on July 7, 1863, with 2,400 mounted soldiers, southern Indiana was unprepared. The Scott County Home Guard had been sent to protect the federal depot at Jeffersonville. Morgan made short work of the feeble defenses at Corydon, killing several home guards, stealing horses, and trashing local businesses. He turned east at Salem, reunified his forces at Vienna in Scott County, and approached Lexington on July 10. Ira Mace of Lexington recalled in 1937 that old men and boys set up an 1812 cannon near the cemetery but fled without firing. “Copperheads, Butternuts, and Knights of the Golden Circle were in a majority in these parts of southern Indiana,” said Mace. “I saw my father pass through our yard with a rifle in each hand. The extra gun belonged to a neighbor who sympathized with the Confederates. He refused to join the bushwhackers so they compelled him to surrender his gun.”81 Two thousand Union troops occupied Lexington the next day as Morgan headed for Ohio.

Confederate general John Hunt Morgan. He was killed on September 4, 1864, after being shot in the back by Union cavalrymen while attempting to escape during a raid on Greeneville, Tennessee. (Library of Congress)

There is no credible evidence that Morgan communicated with Hoosiers in planning the raid, or that he hoped to get help from sympathetic locals. If he had, he would have been disappointed. Residents of Harrison, Washington, and Scott Counties reacted more with anger than with sympathy at having their horses stolen and protection money demanded. There are only a few anecdotal indicators of any cooperation. Samuel Demaree reportedly joined the Confederate army in Kentucky well before the raid and rode with Morgan through Indiana. He was captured in Ohio, paroled, and lived thereafter with his family in Johnson County.82 Harrison Gookins of the Thirty-Seventh Indiana, a native of Delaware in Ripley County, wrote from Descherd, Tennessee, on July 28, 1863: “I heard old Bill Hartley, Ed Ferrer and some more had gone off with Morgan. I would like to see them and help hang them.”83

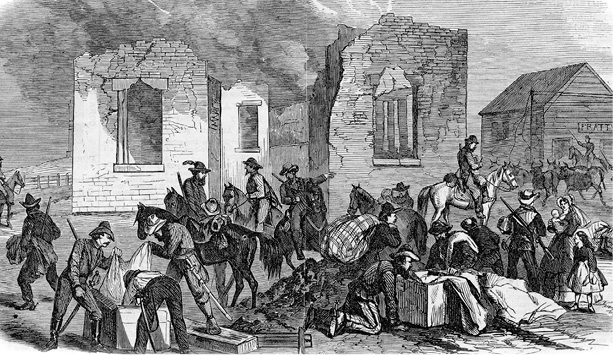

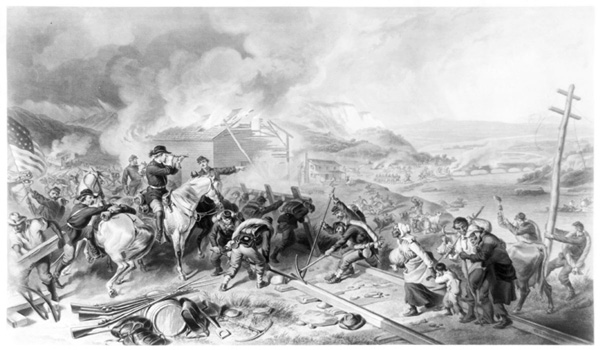

General John Hunt Morgan’s Confederate raiders burn and pillage the depot and stores at Salem, Indiana, on July 10, 1863, in this Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper drawing. (IHS, P 455)

Unified on Color

Added to active disobedience toward the draft was an almost universal rejection of the recruitment of African American troops into the Union army early in 1863. The Madison Courier, New Albany Ledger, and smaller papers throughout the second congressional district criticized the arming of African Americans because they feared the instant leverage they would have with their white counterparts when they returned home. Editors thought African American veterans would be given special treatment for their service when looking for jobs. By the end of 1863, however, sentiment on the black soldier issue had mellowed. Hoosiers realized that for every African American soldier at the front, that meant one less white man had to go and fight.84

The shifting feelings on black troops were typical of the moral dilemma Hoosiers of both political parties faced. While few Hoosiers believed that African Americans should be held in bondage, at the same time they believed that blacks should be segregated in political, social, and military affairs. They wanted African Americans to be free. They just did not want to mix with them. Hoosier sentiment may best have been summed up by Lincoln himself when he said, “Just because I did not want a Negro woman for a slave, I do not necessarily want her for my wife.”85

Prelude to Battle

While southern Indiana boiled, brothers Jacob T. and John J., and cousins, William H. H. and Benjamin, sat before Colliersville, Tennessee, on January 10, 1863, waiting for the expected spring offensive.86 Isaac Newton Kimberlin (Jacob’s older brother) was nearby with the Seventh Missouri Volunteers. It is not known how or why Isaac enrolled in a Missouri unit, except for his matter of fact statement in an affidavit addressed to the Commissioner of Pensions, and signed by Isaac on March 11, 1891. Isaac simply stated: “I enlisted in Co. “G”, 7 Reg., M.O. Inf., May 20, 1861, discharged March 1, 1866.”87 His statement is corroborated by the official record of the Civil War when documenting his later heroism.88 He may have signed up while in Saint Louis on business. We also know that the Seventh Missouri fought alongside the Twenty-Third Indiana at Shiloh, and was consolidated with the Eleventh Missouri in December 1864.

Writing along a railroad track between LaGrange and Memphis, William reported to Jacob “R” back home: “It is supposed that we will go to Vicksburg before long wher thare is a hevy fight expected and it is likely that we will be thare to see the fun. … I will send you some peas that grow in this country they are called Whipowill peas they should be planted about the 15th of April … they are very nice.”89 William’s brother, Benjamin, wrote to Jacob “R” two weeks later from Memphis: “I have not much hope of seeing any of you unless I should live to serve my time out in this war”90

On February 21, 1863, the Twenty-Third Indiana boarded boats to go down river toward Vicksburg, landing at Lake Providence, Louisiana.91 News of the draft reached camp quickly. On March 14 William told Jacob “R” in a letter: “I want you to tell brother John and Hopper if they see that they cant get rid of the draft I want them to volunteer and come to this regiment … that way they can draw their bounty money.”92

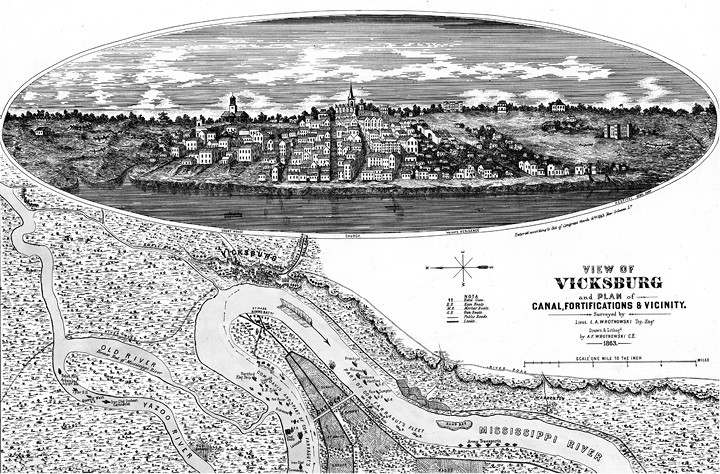

An 1863 view of Vicksburg, Mississippi, showing the city and its fortifications and the deployment of the Union fleet along the Mississippi River. (Library of Congress)

Domestic affairs crept into the Kimberlin correspondence as the Twenty-Third awaited its marching orders. On April 1 Benjamin tried to settle a family dispute in a letter to his sister, Elizabeth. It seemed that his father-in-law, Luther Starkes, was charging Benjamin to board his own daughter, Benjamin’s wife, Sarah, while Benjamin was at war. “I have always paid my just debts so far and I hope to be able to pay them hereafter,” wrote Benjamin. “I expect it will be a snipes bill of the longest kind … he is so prejudiced against me that he could not do me justice… I will make it long in another way.”93

In one of his longest letters of the war, John “J” wrote on April 12 of constant boredom and reflected on everything from “Negroes” to traitors:

Gen. Thomas is here for the purpose of raising a Negro regt. and giving commissions to officers to command them. They are to be stationed on these vacated farms … to raise subsistence for the army and to keep down the guerrilors along the river. … I think it is the thing the Government can do with them for we do not want them in the North I am certain and there is hundreds and thousands of acres that aint doing any body any good unless it is tilled by the negros. … I will fight the rebs with Negroes wolves panthers or elephants, and if I had 10,000 elephants I would turn them all loose and let them thrash the devel out of them. … I know we are accused being abolishionist thieves and murderers in our own state, I care not what burlesks may be heaped upon us we are for the union as it is and constitution as it was [a transposition of a political slogan] … we will show our old copperheads at home that our old flag shall not be insulted.94

John “J” got his wish. On April 22 volunteers were sought from several regiments to board gunboats to run the Warrenton and Vicksburg batteries. John’s brother, Isaac, with the Seventh Missouri, was among the volunteers. John Hardin of Company E, Twenty-Third Indiana, described the run in a letter home: “six of our transports run the blockade the night of the 22nd. We lost one boat, it was sunk. The rest went through without much damage. The officers that belong to the boats would not run the blockade so they had to make details … our boys were anxious to go … only 10 cannonballs and about 2,000 rifle balls went through the boat.”95 Isaac was singled out in the after-action report of Colonel W. S. Oliver, commander of the steamer Tigress, the lead boat, for staying at his post as “a very heavy shot in the stern knocked away three knees and two planks, making an opening of at least 4 feet in her hull … our men put cotton bags into such holes as might be made by their shot. The Tigress received in all thirty-five shots, fourteen of which struck her hull, the last one causing her to fill and settle fast.”96 Isaac survived, but tragedy loomed ahead for the Kimberlins.

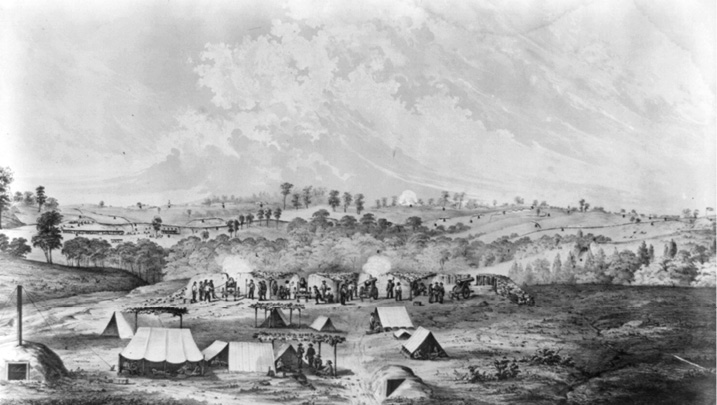

A print depicting the Siege of Vicksburg, showing Union tents and underground bunkers in the foreground. In the distance are Union rifle pits and along the ridge are Confederate forts and earthworks. (Library of Congress)

Vicksburg Campaign

Isaac’s heroics were critical to the eventual success of General Ulysses S. Grant’s strategy to capture Vicksburg. The city, long believed to be even more important than Memphis and New Orleans in controlling the Mississippi River, had withstood three attempts by Union armies to force its capitulation. Both sides agreed on Vicksburg’s strategic role. Confederate president Jefferson Davis described Vicksburg as “the nailhead that held the two halves of the Confederacy together.”97 Lincoln told a gathering of general officers, “Vicksburg is the key. The war can never be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket.”98

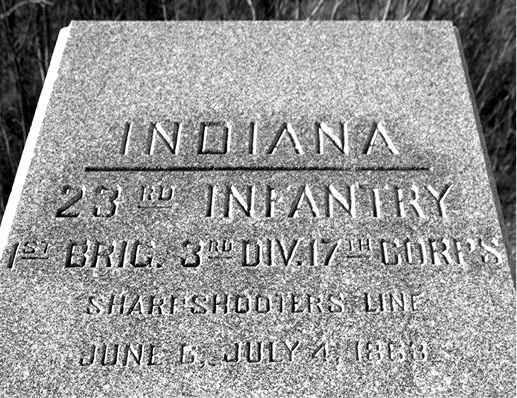

Marker at the Vicksburg National Military Park honoring the Indiana Twenty-third Infantry Regiment (Michael S. Murphy)

Grant was under great pressure to produce results at Vicksburg. As spring 1863 blossomed in the bayous, Grant decided to move south along the Arkansas shore opposite Vicksburg to a point across from Grand Gulf, Mississippi, where he hoped to land 22,000 infantrymen, including the Twenty-Third Indiana. Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter’s gunboats failed to silence the defenses at Grand Gulf, so Grant marched his army five miles south and completed one of the largest amphibious landings in American military history at Bruinsburg, Mississippi, from April 30 to May 1, 1863.99 Grant was now in position to encircle Vicksburg from the east and to lay siege indefinitely. But first, Union forces had to fight their way off the beachhead.

Bruinsburg to Vicksburg

Confederate scouts quickly alerted Generals John Bowen and Edward Baldwin, who rushed forces from Port Gibson and Grand Gulf to the Bayou Pierre, a nearly impenetrable entanglement of undergrowth divided by deep ravines and located west of Port Gibson. On May 1, in a battle known by two names, Port Gibson and Thompson’s Hill, the Twenty-Third helped turn the right flank of Bowen’s Confederate line, forcing the Rebels to fall back through the bayou and Port Gibson. John Hardin was captured there, and William H. was cut down by troops of the Twentieth Alabama under Colonel Isham Garrott.100 William H. H. was one of ten members of the Twenty-Third Indiana killed that day.101

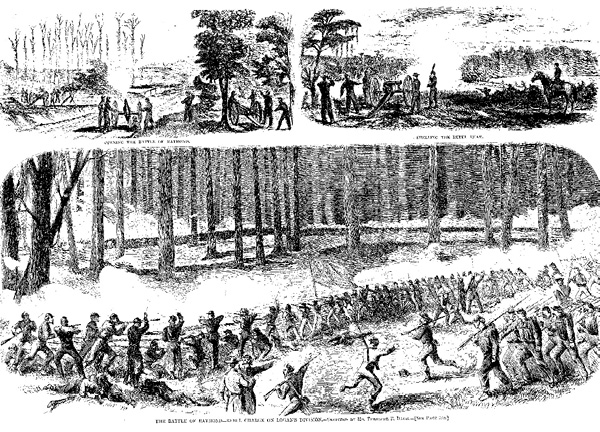

Artist Theodore R. Davis made these sketches showing views of the different stages of the Battle of Raymond fought on May 12, 1863. (Library of Congress)

Grant’s next tactical objective was the railroad connecting the capital of Jackson, Mississippi, to Vicksburg. He moved his army slowly northeast, scouting for the cavalry of Nathan Bedford Forrest and the army of Earl Van Dorn, a native of Port Gibson, as he went. For the second time in six months, Grant split his army at Rocky Springs, sending most of his troops toward Jackson while General John Logan’s division, including the Twenty-Third, moved directly north toward the railroad.102 On May 12, 1863, as Logan’s forces topped a ridge south of Raymond, Mississippi, they saw Confederate forces under General John Gregg blocking their intended crossing of Fourteen Mile Creek. The land between the ridge and the creek is an open plain sloping toward thick woods camouflaging the creek. The Twenty-Third advanced east of the road, next to the 124th Illinois, but became detached and “alone met the onslaught of five confederate regiments, two on one side and three on another, being almost entirely surrounded … with fixed bayonets and clubbed muskets, they successfully emerged from what seemed to be an almost hopeless position, fell back to the main line, reformed, and continued in the engagement.”103 Benjamin was shot dead by soldiers of the Third Tennessee before he could reach the creek, about midday.104 Regimental physician McPheeters described the battle to his wife, Mollie: “Been in four hard fights, one at Thompson’s Hill about which I wrote you, and the fight at Raymond, in which our regt. fought and lost guite a number killed and wounded.”105 Benjamin never got to pay his wife’s rent.

Writing of his cousin’s death, Jacob T. Kimberlin told Jacob “R”:

I was in the hospital at Grand Gulf when the battle of Raymond was fought … it was there that your brother Benjamin was killed. … William having ben killed at Thompson’s Hill. … Raymond was a desperate encounter. Far hotter than our regiment was ever in before or since. The Rebels were quickly driven back but not until they had killed 16, wounded more than one hundred, and captured 23. And all of this was done in the astonishly short space of a few minutes … all of Ben’s things were lost. Everything being taken from his pocket by the Rebels. He was buried by the side of Lt. Henry C. Dietz who was killed about the same time and but a short distance from the same place. The graves of both men are marked with their names and the regt. to which they belonged.106

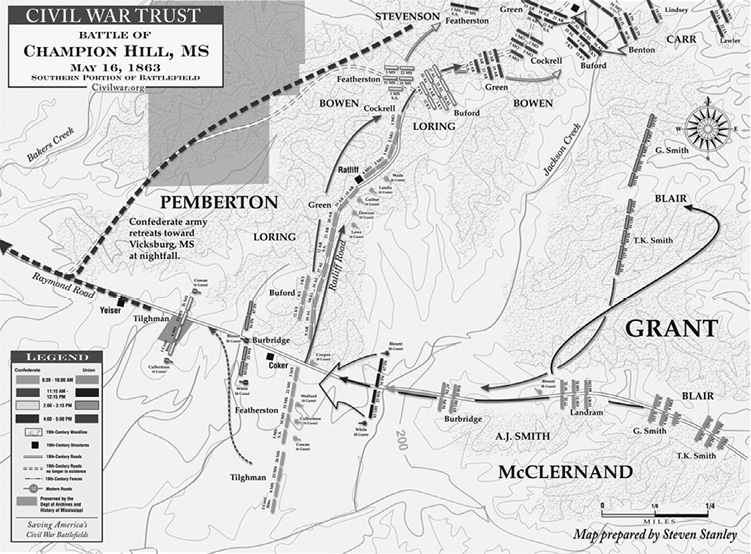

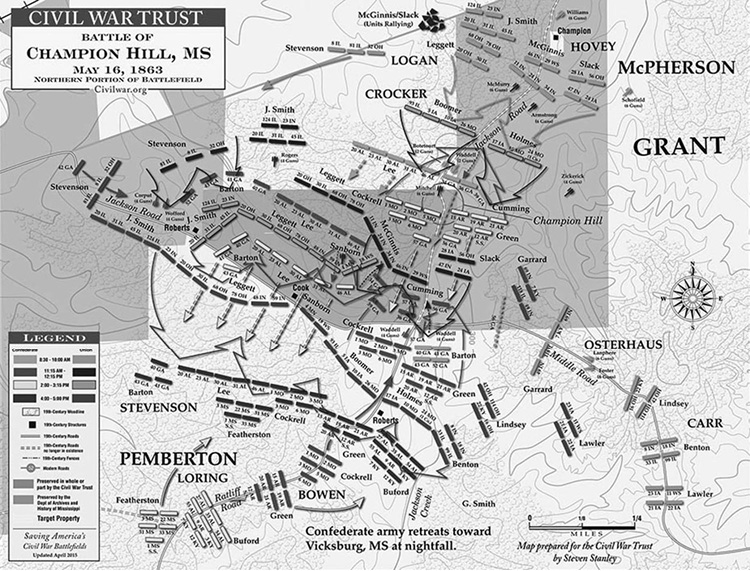

When Grant arrived at Jackson, he found most of the Confederate troops had evacuated the city and moved west to guard the approaches to the Black River. Grant’s troops torched Jackson and reunited with Logan’s division on May 16, 1863, near Bolton, along the Southern Railroad of Mississippi. There, near the crest of Champion’s Hill, the forces of Van Dorn fought desperately to block Logan’s and General Alvin Hovey’s divisions from reaching the Black River. During a five-hour battle, Union troops took and retook the fields around the Champion House, with the Twenty-Third Indiana, under Colonel William Sanderson (of General John E. Smith’s brigade), eventually pushing General Seth Barton’s Fortieth Georgia into a general retreat. As at Raymond four days earlier, Confederate forces were not defeated decisively but withdrew from the field toward Vicksburg.107 After one more battle of moderate severity at the Black River crossing on May 17, 1863, Van Dorn’s forces holed up inside the defensive perimeter at Vicksburg and awaited a long siege.

Courtesy Civil War Trust

Vicksburg

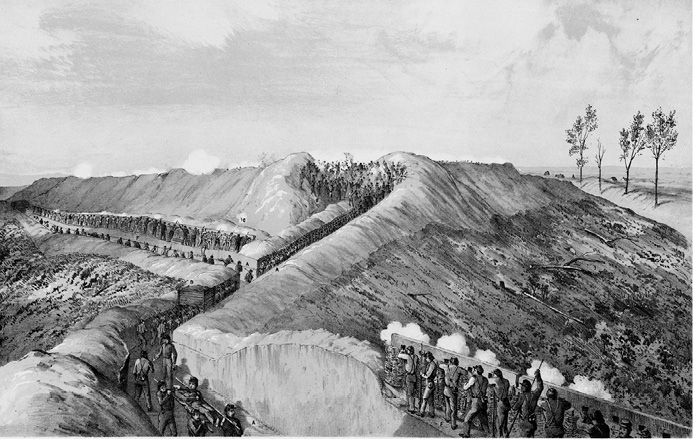

The Vicksburg defenses consisted of massive batteries on the bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River, and a crescent on the north, east, and south perimeters, consisting of nine forts connected by a system of trenches. The Twenty-Third Indiana was in the front line of the siege at Vicksburg, stationed along the White House Road, directly within range of Confederate troops manning the Third Louisiana Redan. On May 22, 1863, three days after a hastily ordered assault on the Vicksburg works had failed, Grant ordered a general assault along a three-mile front. The Twenty-Third, in tandem with the Forty-Fifth Illinois, gained the crest of the Third Louisiana Redan, only to be pushed back to the base. On June 25, in an eerie precursor to the infamous mine explosion at Petersburg one year later, Logan’s division finished an excavation under the same redan, and ignited 2,200 pounds of black powder. Again, the Twenty-Third rushed into the crater and fought for the breech with bayonets and hand grenades. Logan sent regiment after regiment into the crater for more than twenty-six hours, but the assault failed and both sides settled down into trench warfare again.108

A print showing Union soldiers in trench and behind wooden walls and gabions as an assault is made on Fort Hill during the siege of Vicksburg. (Library of Congress)

Starved and diseased more than they were defeated, Confederate troops under General John Pemberton surrendered on July 4, 1863, one day after Robert E. Lee’s Confederate army lost at Gettysburg. From May 21 to July 4, 1863, the Twenty-Third lost fifty-five men killed and wounded.109 Jacob T. was one of those wounded. Writing from an unnamed regimental hospital on June 13, he told Jacob R: “I am at present in our regimental hospital from the effects of a wound I received on the 4th instant. I rejoined the regiment after having left the hospital [Grand Gulf] on the 3rd June, and on the ensuing day was shot through both hips while going for water. I have been in the hospital ever since. I am doing quite well, and hope to be able to inform you of my rapid recovery soon.”110 Jacob T.’s luck did not hold. On August 2, his older brother, Isaac, wrote home to cousins Jacob F. and Jacob “R”: “I have bad news to write this evening. Brother Jacob died at 9 o’clock this morning and will be intered some time tomorrow at Greenville. Sister Mary will be at viena on next Wednesday and warrent I will try to meet her there. … I expect to come with her if I can get off … excuse these few lines, and consider me your cousin, I.N. Kimberlin”111

Momentum and the March

Morton’s and the Republican Party’s fortunes changed for the better after the Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg. There was a sense in Indiana that the war was finally turning in favor of the Union. While resistance to the draft persisted, and Morton continued to suppress opposition newspapers under the cover of General Order Number 38 (editors in Plymouth and South Bend, for example, were arrested because of their editorials), the Indiana economy continued to chug along and the flow of volunteers made the draft almost unnecessary.112 Most of the surviving members of the Twenty-Third Indiana, for example, reenlisted for “three years more, or until the close of the war.”113

The Twenty-Third stayed at or near Vicksburg through the winter of 1863, joining other regiments from time to time for sorties to Monroe, Louisiana; Canton, Missouri; and Meridian, Mississippi, to destroy railroads and to disrupt the ability of Confederate troops to concentrate for a spring campaign. The threat of a land-based Confederate attack was pervasive. Isaac participated in reinforcement of the fortifications around Vicksburg after he returned to his regiment from an illness, writing on November 3, 1863, his birthday, “We will Soon have the Breast works done, the most formidable in the united states all the Southern Army could not Shake it or take the place once complete.”114

Just after Christmas, Isaac wrote home to an engaged Jacob R., in anticipation of a leave: “Though I am very satisfied where I am yet I believe I could enjoy a visit to old Scott for a few Days. Jake I heard that you was about to put the thing through with Sally and I believe it is pretty well founded. Now Jake I have one word to say on this subject, and that is, Don’t try on your vest until I come home Jake I weigh 165 I am as fat as a bear and still thriving As I expect to see you Soon I will come by.”115 In March 1864 the regiment left Vicksburg for New Albany by boat for its official thirty-day “veterans leave.”

We do not know how the Kimberlins and their cousins, the Whitlachs and Houghs, spent their leave in Scott County. Because they were at home there was no need to write letters. It is safe to assume that they did exactly what they had looked forward to doing: catch up with the women, help out on the farm, and give the family more details about how their sons and brothers had died. While at home, the war continued without them. Forrest captured the old headquarters of the Twenty-Third, Paducah, in late March 1864. On April 12 Forrest captured Fort Pillow and massacred several hundred “colored” troops after they had surrendered. Farther south that same day, the Twenty-Third’s fighting comrades, the XVII Corps, helped disperse Confederate General Tom Green’s cavalry division as it tried to capture Union transports and armament on the banks of the Red River at Pleasant Hill Landing.

Union general William Tecumseh Sherman and his staff pose for the camera at federal Fort Number 7 near Atlanta, Georgia, July 18, 1864. (Library of Congress)

Amidst the various military campaigns, campaigns of another sort were also being played out: the re-election campaigns of Lincoln and Morton. Despite the attempt of Peace Democrats such as Daniel Voorhees to promote the candidacy of General George B. McClellan for president in 1864,116 Indiana historian Emma Lou Thornbrough noted that “war weary Indianians generally accepted the re-nomination of Lincoln without great enthusiasm.”117 That did not mean Morton was at ease. He stepped up his warnings about traitorous activities, culminating in the arrest of Lambdin Milligan and his alleged fellow plotters of the Northwest Conspiracy. Morton justified his actions on the basis of accomplishing a higher moral goal. “If we use all the means within our reach, it is within the power of the Union Party to save the state,” he wrote.118 The timing was perfect for Morton, considering that the October election (November for president) came just weeks after General William T. Sherman’s victory at Atlanta and General Philip Sheridan’s victory in the Shenandoah Valley. These triumphs for the Union, combined with the uproar about the “treason trials” by a military court in Indianapolis, made it very difficult for anyone to boldly announce against Morton without looking like a fool at best or a traitor at worst.

General Sherman’s troops destroy Confederate railroad tracks and buildings on its March to the Sea through Georgia from November 15 to December 21, 1864. (Library of Congress)

Morton also strategized to maximize the assured friendly vote of Hoosier soldiers in the field. In letters to Lincoln and Secretary of War Stanton, Morton urged mass furloughs for Indiana troops, arguing that without their vote his future and Lincoln’s as well were precarious. Stanton opposed the furloughs, but Morton prevailed on Lincoln to allow sick and wounded soldiers a thirty-day reprieve. The governor sent agents to visit Indiana regiments to poll them on the presidential and gubernatorial races, and to encourage those eligible to come home. One aide suggested to Morton not to bring home the Fifty-Ninth regiment because its members and most of its officers were “coppers.”119

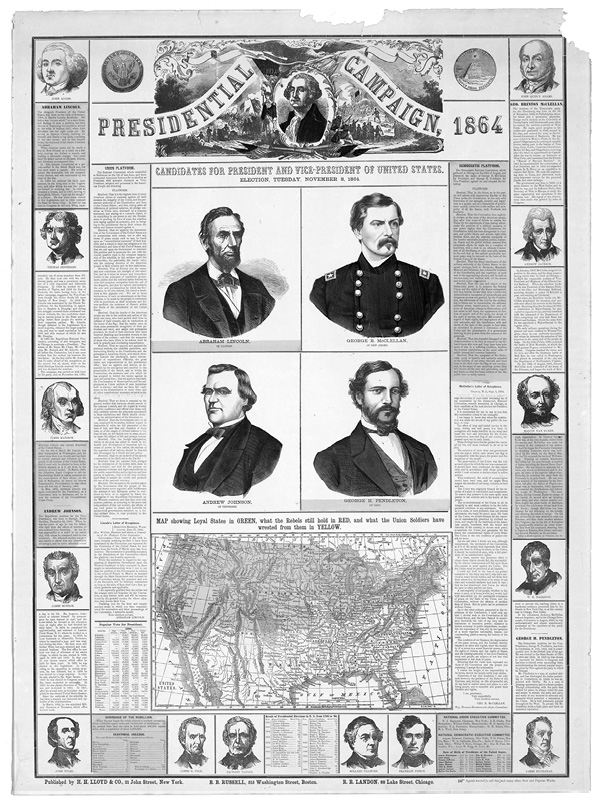

A print showing the contenders for the 1864 presidential election, including the Republican ticket of Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson, and the Democratic ticket of George B. McClellan and George H. Pendleton. Bust portraits of the previous presidents run around the edge of the print. (Library of Congress)

Posted with the Seventh Missouri at the mouth of the White River in Arkansas, Isaac opined on the election in a September 25, 1864, letter to cousin Jacob R.: “Well Jake perhaps you would like to know my opinion about Abe and the election. Well If I had a hundred thousand Dollars I would bet that Abe would be re-elected. And if I had that many votes I would Shove them all to Abrahams bosom, the officers took a vote of our Division and little Mc got about one vote out of every hundred, friemont [Charles Fremont] none.”120

In the end, 9,000 Hoosier soldiers returned home to vote. Morton probably did not need the furlough program to seal his victory. Indiana went for him by a margin of 20,000 votes. Republicans won eight of eleven congressional seats, almost a complete reversal of 1862, even defeating Morton’s nemesis, Voorhees, in his re-election bid for Congress.121 Republicans also retook both houses of the Indiana legislature. Calvin Fletcher said anyone who voted for McClellan and the Democrats was a “traitor and a copperhead.”122

Judging by the Scott County vote in 1864, there were plenty of traitors and copperheads in residence there. The county maintained its political tradition after 1850 of electing to local, state, and federal office Democrats who were fiercely independent of mainstream thinking, while generally maintaining a loyal if not effusively pro-Union attitude as secession and civil war occurred. Men such as Cravens, Bright, English, and Heffren kept up their loyalist behavior while excoriating Lincoln, Morton, Stanton, and other Republican leaders as men willing to go beyond the Constitution to preserve a Union that should not be preserved without the consent of their southern brethren.

While Scott County landed solidly in the Democrat camp, the underlying split between those who believed in “the Constitution as it is, the Union as it was,” and those who believed that their true interests lay with the South, was never resolved during the Civil War. Scott County’s sentiment can best be described as a strange comingling of philosophies that might seem contradictory to an outsider. A Scott County motto of 1864 might have read, “Union, yes, but Southern at heart and in soul.”

An Awful Price for Union

The two primary Kimberlin regiments, the Twenty-Third Indiana and Sixty-Sixth Indiana, eventually rejoined on June, 9, 1864, at Ackworth, Georgia, to fight under Sherman in his Georgia campaign and his March to the Sea. Both regiments saw action at Kennesaw Mountain, Nickajack Creek, Peach Tree Creek, and the battle of Atlanta, where General James McPherson was killed.123 Six more Kimberlins would be strewn on battlefields and in hospitals across the South. Those who lived marched with Robert Armstrong of Horner’s Chapel, Indiana, and Doctor McPheeters of Livonia through North Carolina and Richmond and on to Washington, D.C. In his war diary, Armstrong wrote about arriving on battlefields (Altoona) and “being almost sickened at the sight.”124 But there were lighter moments as well. McPheeters wrote to Mollie of the celebration of Lee’s surrender, in camp at Goldsboro, North Carolina, on April 9, 1865: “some 15 or 20 boys from the 22nd Indiana came here last night dressed in women’s clothes. … Brought their music along for a dance … their spitting tobacco juice was no evidence that they were not women … they danced till they got tired, then went home highly pleased.”125 One of Armstong’s last diary entries simply reads: “spent the day at the Capitol and the Patent Office, get some pictures for my album.”126

General James McPherson’s death at the Battle of Atlanta made him the second highest ranking Union officer killed during the war. (Library of Congress)

Chapter 4 Notes

1. Emma Lou Thornbrough, Indiana in the Civil War Era, 1850–1880 (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau, 1989), 86–87.

2. Thomas J. Kelso, “The German-American Vote in the Election of 1860: The Case of Indiana with Supporting Data from Ohio” (PhD diss., Ball State University, 1967), 119.

3. Ibid., 132.

4. Ibid., 132–33, 143.

5. Ibid., 11.

6. “Abstract of Votes Cast in 1860 for Governor, Lieutenant Governor and State Offices,” Indiana Secretary of State, Microfilm Roll Number 6617, Indiana State Archives, Indianapolis, IN.

7. Ibid.

8. “Abstract of Votes Cast for Representative in Congress for 1860 by Congressional District,” Indiana State Archives.

9. Wood Gray, The Hidden Civil War: The Story of the Copperheads (New York: Viking Press, 1942), 240.

10. Jesse Bright, “Some Letters of Jesse Bright to William H. English, (1842–1863),” Indiana Magazine of History 30 (September 1934): 370.

11. E. Duane Elbert, “Southern Indiana in the Election of 1860: The Leadership and the Electorate,” Indiana Magazine of History 70 (March 1974): 13.

12. Walter Dean Burnham, Presidential Ballots, 1836–1892 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1955), 390–408.

13. Jesse Bright, “Some Letters of Jess Bright to William H. English,” Indiana Magazine of History 30 (September 1934): 385.

14. William Dudley Foulke, Life of Oliver P. Morton, 2 vols. (Indianapolis: Bowen-Merrill, 1899), 1:93.

15. Indianapolis Sentinel, April 11, 1861.

16. Lorna Lutes Sylvester, “Oliver P. Morton and Hoosier Politics during the Civil War” (PhD diss., Indiana University, 1968), 50.

17. Ibid.

18. Thornbrough, Indiana in the Civil War Era, 103.

19. Kenneth Stampp, Indiana Politics during the Civil War (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau, 1949), 73.

20. Thornbrough, Indiana in the Civil War Era, 117.

21. Hamilton Family Papers, July 26, 1861, L62, Indiana State Library, Indianapolis, IN.

22. Sylvester, “Oliver P. Morton and Hoosier Politics during the Civil War,” 65.

23. Arville L. Funk, Hoosiers in the Civil War (Chicago: Adams Press, 1967), 50.

24. Benjamin Kimberlin to Jacob R. Kimberlin, May 26, 1862, Kimberlin Family Papers, private collection (hereafter cited as Kimberlin Papers).

25. John D. Barnhart, “The Impact of the Civil War on Indiana,” Indiana Magazine of History 57 (September 1961): 200.

26. Muster Rolls, Indiana State Archives.

27. Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Indiana, 8 vols. (Indianapolis: Samuel M. Douglass, State Printer, 1865–69), 2:612.

28. Muster Rolls.

29. Kenneth Hafendorfer, Battle of Richmond, Kentucky (Louisville: KH Press, 2006), 36.

30. Ibid., 141.

31. Ibid., 217.

32. Ibid., 303.

33. Catharine Merrill, The Soldier of Indiana in the War for the Union, 2 vols. (Indianapolis: Merrill and Company, 1866), 1:606–9.

34. A Chronology of Indiana in the Civil War (Indianapolis: Indiana Civil War Centennial Commission, 1965), 49.

35. Jacob R. Kimberlin to Isaac Jones Kimberlin, July 30, 1862, Kimberlin Papers.

36. Isaac Jones Kimberlin to Jacob R. Kimberlin, August 22, 1862, ibid.

37. Jacob R. Kimberlin to Isaac Jones Kimberlin, September 4, 1862, ibid.

38. Sylvester, “Oliver P. Morton and Hoosier Politics during the Civil War,” 130.

39. Indiana State Sentinel, September 22, 1862.

40. Frank Klement, Copperheads in the Middle West (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1960), 1.

41. Mayo Fesler, “Secret Political Societies in the North during the Civil War,” Indiana Magazine of History 14 (September, 1918): 203.

42. Ibid., 186–87.

43. Ibid., 200.

44. Foulke, Life of Oliver P. Morton, 380.

45. Paoli Eagle, January 21, 1861.

46. Brevier Legislative Reports Embracing Short-hand Sketches of the Debates and Journals of the General Assembly of the State of Indiana, 17 vols. (Indianapolis: Daily Indiana State Sentinel, 1859–88), 4:5–6.

47. Robert N. Scott, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, series 1 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1902), 23, pt 2:237.

48. Fesler, “Secret Political Societies in the North during the Civil War,” 232.

49. Ibid., 208.

50. Report of the Judge Advocate General on “The Order of the American Knights,” Alias “The Sons of Liberty”: A Western Conspiracy in the Aid of Southern Rebellion (Washington, DC: Chronicle Printers, 1864), 6.

51. Fesler, “Secret Political Societies in the North during the Civil War,” 185.

52. Ibid., 186, 189.

53. Ibid., 251.

54. Ibid., 211.

55. Klement, Copperheads in the Middle West, 205.

56. Frank Klement, Lincoln’s Critics: The Copperheads of the North (Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Books, 1999), 231.

57. Klement, Copperheads in the Middle West, 89.

58. Klement, Lincoln’s Critics, 159.

59. Sylvester, “Oliver P. Morton and Hoosier Politics during the Civil War,” 151–52.

60. Ibid., 176.

61. Ibid., 268.

62. Stephen E. Towne, Surveillance and Spies in the Civil War: Exposing Confederate Conspiracies in America’s Heartland (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2015), 6–7.

63. Madison Daily and Evening Courier, November 4, 1862.

64. Sylvester, “Oliver P. Morton and Hoosier Politics during the Civil War,” 185.

65. Foulke, Life of Oliver P. Morton, 198–99.

66. Ibid., 255.

67. Charles Carlton, Charles I: The Personal Monarch (London: Routledge, 1995), 354.

68. Madison Daily and Evening Courier, February 24, 1863.

69. March 19, 1863, Sarah Waldschmidt Young Bovard Diary, Scott County Historical Society, Scottsburg, IN.

70. April 14, 1863, ibid.

71. April 22, 1863, ibid.

72. October 4, 1863, ibid.

73. November 25, 1863, ibid.

74. James A. Adams to Catherine Allison, May 17, 1864, James A. Adams Civil War Letters, 1862–1865, William Henry Smith Memorial Library, Indiana Historical Society.

75. Mollie McPheeters to John McPheeters, June 15, 1863, John S. McPheeters Correspondence and Records, 1863–1910, Indiana Historical Society (hereafter cited as McPheeters Correspondence and Records).

76. George McPheeters to Mollie McPheeters, July 1, 1863, ibid.

77. Oliver P. Morton Letters, Indiana Historical Society.

78. Kenneth Stampp, “The Impact of the Civil War upon Hoosier Society,” Indiana Magazine of History 38 (March 1942): 13.

79. Nora Lewis Dupraz, “A Civil War Story from Vevay,” Indiana Magazine of History 35 (June, 1939): 158.

80. Scott County Journal, September 4, 1924.

81. Lexington: A Pioneer Town (Lexington Historical Society), 1988.

82. Vincent Akers, ed., The Demaree Papers: Letter 1854–1875 (Np., 1970), xi.

83. William Henry Harrison Gookins, “Civil War Letters of Harrison Gookins, a Soldier,” Indiana Writes 1, no. 3 & 4 (1976): 24.

84. Thornbrough, Indiana in the Civil War Era, 138–39.

85. Speech by the Hon. Abraham Lincoln at Chicago, given June 26, 1857, in Response to Mr. Douglas, Chicago, IL, July 10, 1858, in Joseph Fornieri, The Language of Liberty (Chicago: Regency, 2004), 218.

86. Henry C. Adams Jr., Indiana at Vicksburg (Indianapolis: Indiana-Vicksburg Military Park Commission, 1910), 248

87. Civil War Pension Application Number 965710, Certificate Number 617882, National Archives, Washington, DC.

88. Scott, War of the Rebellion, 24, pt. 1:566–67.

89. Kimberlin Papers.

90. Ibid.

91. John S. McPheeters, “A Brief History of the 23rd Regiment of Indiana Volunteers,” unpublished manuscript, McPheeters Correspondence and Records.

92. Kimberlin Papers.

93. Ibid.

94. Ibid.

95. John J. Hardin Papers, MS174, L209, Guide to the Indiana Sesquicentennial Manuscript Project: Part 1, Indiana State Library.

96. Scott, War of the Rebellion, 24, pt. 1:566–67.

97. Terrence J. Winschel, Triumph and Defeat: The Vicksburg Campaign (New York: Savas Publishing, 1999), 143.

98. Ibid., 142.

99. Ibid., 58.

100. Terrence Winschel, interview with the author, Vicksburg National Battlefield Park, March 6, 2006.

101. Adams, Indiana at Vicksburg, 249.

102. Winschel, Triumph and Defeat, 93.

103. Adams, Indiana at Vicksburg, 250.

104. Author reconnaissance of site and Winschel interview.

105. John McPheeters to Mollie McPheeters, McPheeters Correspondence and Records.

106. Kimberlin Papers.

107. Winschel interview.

108. Ibid.

109. McPheeters, “Brief History of the 23rd Regiment of Indiana Volunteers.”

110. Kimberlin Papers.

111. Ibid.

112. Thornbrough, Indiana in the Civil War Era, 191.

113. Adams, Indiana at Vicksburg, 252.

114. Isaac N. Kimberlin to “Brother and Sister,” November 3, 1863, Kimberlin Papers.

115. Isaac N. Kimberlin to Jacob R. Kimberlin, December 28, 1863, ibid.

116. John C. Waugh, Reelecting Lincoln: The Battle for the 1864 Presidency (New York: Crown Publishers, 1997), 335.

117. Thornbrough, Indiana in the Civil War Era, 210.

118. Waugh, Reelecting Lincoln, 333.

119. Thornbrough, Indiana in the Civil War Era, 220.

120. Isaac N. Kimberlin to Jacob “R.,” September 25, 1864, Kimberlin Papers.

121. Waugh, Reelecting Lincoln, 335.

122. Calvin Fletcher Diary, November 9, 1864, The Diary of Calvin Fletcher, 9 vols. (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society, 1972–83), 8:465–68.

123. Adams, Indiana at Vicksburg, 253.

124. October 6, 1864, in “Civil War Diary of Robert Armstrong, Sergeant, 66th Indiana Infantry, 1862–1865,” typescript, Allen County Public Library, Fort Wayne, IN.

125. John McPheeters to Mollie McPheeters, April 9, 1865, McPheeters Correspondance and Records.

126. May 30, 1865, “Civil War Diary of Robert Armstrong.”