19

Pasalubong

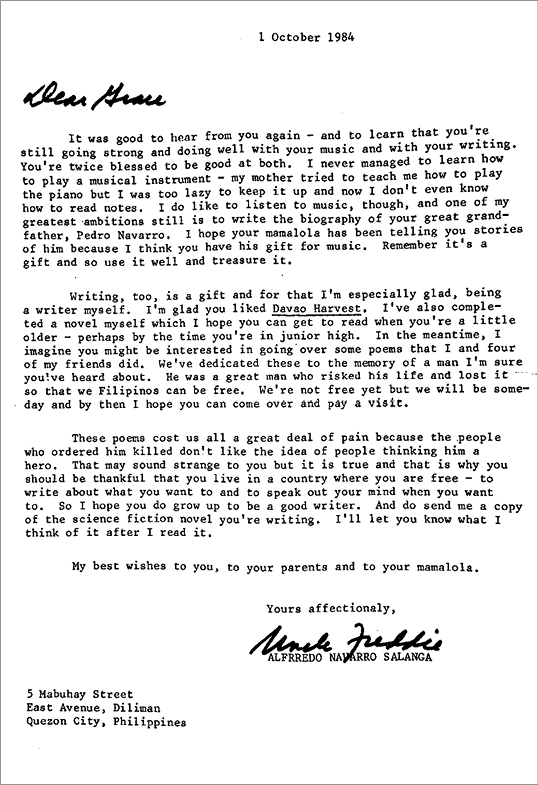

Alfrredo Navarro Salanga in the 1980s. Photo: Wig Tysman.

As a child, if it weren’t for my maternal grandmother’s yearly visits from the Philippines, I would not have been certain that such a place existed beyond my family’s stories. Mama Lola was as real as the fairy godmother in Cinderella. She swooped in once a year bringing dried watermelon seeds, milk candies, and stories of this fantasyland called Manila, only to vanish without a trace. When Mama Lola noticed that I always had a book in front of my face, she told me about her nephew, Alfrredo Navarro Salanga, who was a prolific writer of journalism, poetry, fiction, criticism, even plays.

“You are becoming like your Tito Freddie,” she told me.

I didn’t believe Mama Lola. I could not conceive of anyone who looked like me as the author of a book.

Mama Lola told me to write Tito Freddie a letter and she promised to hand-deliver it to him. So, in 1982, at ten years old, I wrote him a letter and forgot about it.

A letter to Grace from Tito Freddie.

The next year, my grandmother returned with a letter tucked into a softcover book titled Davao Harvest, by Alfrredo Navarro Salanga. I was amazed. Here was an actual book written by a real writer who was related to me. Back then, I often spent weekends at the public library, but had never encountered a book by a Filipino.

One of the conditions of early childhood is that you must ask for nearly everything that you want. Some objects are out of reach — the ice pops in the freezer — and permission is a constant requirement. Can I play outside? Can I watch TV? Can I have a glass of water? There was always the risk of No, and the disappointment, frustration, shame, and longing that accompanied rejection.

The one place I didn’t have to ask for permission was in the children’s wing at the Ames Free Library. I earned the right to a library card in the first grade by proving I could form the letters to my first and last name on the application. The librarian led me to the picture-book corner where the shelves were my height. There on the red leather bench under the picture window, I found my answers to questions about life and eased my loneliness.

The library was a gift from the Ames family, who made their fortune manufacturing shovels, and I accepted this gift every week. As my mother waited parked out front, I climbed the long walkway to the library’s entrance, a low arch trimmed in Longmeadow sandstone, the wooden doors hidden to the left of the entrance on the porch. Later, I learned about the Chinese men who dug the railroad using those Ames shovels. But as a child, all I cared about was getting my books.

I pushed through the dark doors into the library. It was as quiet as a church and just as mysterious. The one toilet in the cellar required a skeleton key and a walk down a narrow spiral staircase, where you were met with the ghostly marble bust of the library’s benefactor, Oliver Ames II. Only library staff was allowed to fetch the books from the balcony under the barrel-vaulted ceiling.

My library card was a house key to my true home. Well before I was actually an adult, I was allowed to cross the border into the adult section. When I searched the wooden card catalog, I would always go to the drawer with 959.9 of the Dewey Decimal System and read the name of the place I had come from, which no one had ever heard of.

The summer before I entered college, I worked as a clerk in the library and sat at the glass-topped desk dreaming of who I would become. All that time, I had never thought about all the people who had written the books on the library shelves. The adults I knew were doctors, nurses, teachers, and housewives. And yet, almost a quarter century later, I became a writer. I found stories in that Richardson building early in my life and never stopped looking for more.

*

When it came time for Mama Lola to return to the Philippines, I wrote Tito Freddie another letter where I told him how much I loved his book, even though I was eleven and hadn’t been able to make any sense of it.

In October of 1984, my grandmother delivered another letter from Tito Freddie, the only one that I still possess, along with In Memoriam: A Poetic Tribute by Five Filipino Poets. Tito Freddie wrote:

These poems cost us all a great deal of pain because the people who ordered him killed don’t like the idea of people thinking him a hero. That may sound strange to you but it is true and that is why you should be thankful that you live in a country where you are free—to write about what you want to and to speak out your mind when you want to.

He was referring to Benigno Aquino Jr, a Filipino senator and long-time political opponent of the Marcos dictatorship who was assassinated in 1983. Aquino had heard rumors that he might be killed if he ever returned to the Philippines, so he invited the press to accompany him on the airplane to Manila so that they might tell his story if he died. There is video footage of the moment before Aquino is shot in the head. He walks through the aisle, steps through the doorway, and meets the bullets. I saw Aquino’s clothes displayed in his former home in Newton, Massachusetts, where he had lived in exile. The shirt and pants had stiffened with blood.

I was not yet a teenager, but I was old enough to understand the gravity of what Tito Freddie had written. He picked his words carefully, making me realize how powerful writing could be. Before that day, I had never thought of myself as lucky to live in the U.S. I had taken my freedom of speech for granted.

In the same letter about Aquino, Tito Freddie wrote, “He was a great man who risked his life and lost it so that we Filipinos can be free. We’re not free yet but we will be someday, and by then I hope you can come over and pay a visit.”

Tito Freddie died before we could meet in person, but his conviction taught me that a writer sets words down, one after the other, which offer new, expansive possibilities.

*

Now, I’ve kept my promise to my uncle and have returned to the Philippines on a Fulbright fellowship. Midway through my life, I am living in Manila for half a year. My official reason for being here is to work on a research project, but my true motivation is to reconnect with the country that I left as a toddler. What does it mean to have lived most of my life in a different country from the one I had started in?

Once in Manila, I look for signs of Tito Freddie in libraries and bookstores, at his alma mater the Ateneo, at his widow Alice’s apartment, and finally at his grave. I read his books; I touch his awards; I flip through hundreds of pages of correspondence, “Thank You” notes that show how generous he was with his time and resources, rejection letters from schools in the U.S. where he had hoped either to study or to teach, and surprisingly warm requests for payment from a bill collector that become sweeter the more time passes.

My aunt Alex once told me that she had read the letters I had written Tito Freddie. “How is that possible?” I asked.

She had seen them on display. I was embarrassed that my deepest girlhood yearnings had been exhibited. Tita Alex has since passed away, and no one I’ve asked has ever heard of my letters. I looked, but I didn’t find them in the Ateneo archives. Without physical proof, I started to question whether I had even written them—a psychological pattern that I think is intertwined with the immigrant experience. My life in the Philippines had become as believable as a dream.

*

My friend Howie tells me that Freddie “was a writer in the worst of times. He had close friends who were killed by the military; he himself was jailed. He knew that he had gifts that had a higher purpose than just fame and fortune. He gave young writers the gift of his example, time, and attention. He knew that we would grow up and develop into people who could make a difference.”

Tito Freddie did not just write poems, novels, short stories, and plays, he also wrote newspaper columns and articles. He was imprisoned for several months during Martial Law for writings critical of the dictatorship. Today, the Philippines is still considered a deadly place to practice journalism, and a bottleneck in the judicial system and a culture of impunity means there is no justice for victims and their families.

*

Across time zones and the globe, Ann messages me the image of my 1984 letter from Tito Freddie while I am visiting Alice, Freddie’s widow. We sit together at her dark apartment and she cries as she reads it. In the letter, he describes a project he wants to write, a biography of our common ancestor, Captain Pedro Navarro, and she cries. It’s one of many projects he did not have time to complete before his death. After a series of debilitating medical problems, in 1988, Tito Freddie died.

“He wrote beautifully, didn’t he?” she says.

Periodically, she pulls a book out from the shelf behind her and reads a favorite poem aloud. Alice does numerology on my birth date and warns me to watch my temper. She explains the second “r” in the spelling of Alfrredo as a decision he made to change his fortune after she read his numbers. Then we share a meal: adobo, home-fermented cabbage, and squares of chocolate from a candy bar for dessert. We talk about the hard times the family faced after Tito Freddie’s death. There were medical bills to pay and children to get through school. They moved residences many times and along the way, Alice sold Freddie’s book collection, over seven thousand of them, as many as the Philippines had islands, to help pay the bills. A mouse suddenly falls from a hole in the rotting ceiling tile, looks at us, and scampers under a pile of papers.

The only people I’ve met in the States who know Freddie’s work have studied Filipino literature, whereas almost everyone I ask in Manila is not only familiar with his work, but had known him personally. His roots in the literary community were deep.

A few days after visiting Alice, I kneel at Freddie’s grave and run my finger across the stone. Although this is my first visit, I’ve walked past it many times to visit my grandparents and godparents a few rows away. Tito Freddie is buried steps away from the same grandmother who would hand-deliver his letters and books to me in Boston. His epitaph, “The carpenter no longer sings,” comes from a poem he wrote after Aquino’s assassination. Long after I leave his grave at the cemetery and his papers at the archive, these words continue sounding in my ears.

Tito Freddie’s gravesite, whose headstone reads,

“The carpenter no longer sings.” Photo: Alonso Nichols.