4

Little Bud

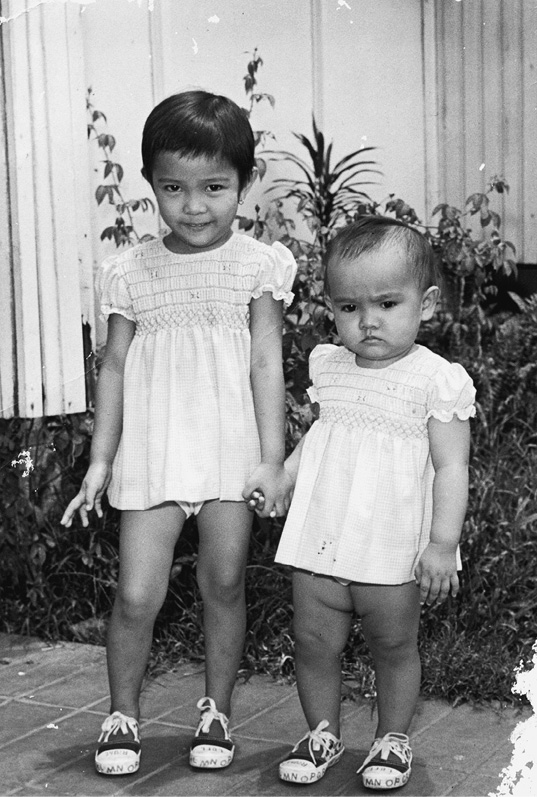

Grace at age 2 with Tessie,

her older sister, at the family compound.

Before my family emigrated from Manila, I lived on a compound with blood relatives. It was our own tiny village enclosed by a wall planted with broken glass and sharp metal pieces at the top. This kept the danger out, and it also made it difficult for the teenagers and husbands to sneak out at night.

Someone always knew your business; you were never alone. Our family lived together, ate together, and prayed together. We were a large family, Catholics like the majority of the country. I was surrounded by dozens of cousins who called me by my nickname, Bubut, or Little Bud, and liked to pick me up and pinch my cheeks since I was so roly-poly. I blame my titas, those aunties who liked a fat child. They fed me constantly, especially camote, sweet potato slices fried in lard then dredged in sugar, which melted like snow on the hot coins then hardened into a shell. They liked to watch my joy as I ate.

At night, the small children glowed white with talcum powder after their baths, and the older cousins told stories until the babies’ clean hair dried.

Secret histories of the family were shared: The speculation about which of the cousins were not true-blood. The story about the Muslim uncle from the south who moved to Manila as a boy when the priests offered to educate him. All he needed to do in exchange was convert to Catholicism. His family held funeral rites for him, and my uncle realized that there were ways to die before you died. Or the story of how my mother’s mother, Mama Lola, was haunted by the faint sound of a crying baby, perhaps the unborn soul of her last miscarriage, and how she roamed the grounds some nights, trying to find her child.

After my mother’s father Lolo died, the families on the compound feuded for months, confusing grief with anger. They stopped talking to each other, and the once vibrant compound fell quiet. On New Year’s morning, Lolo’s favorite holiday, the family broke their silence, all the kinfolk complaining of poor sleep. Someone had been knocking on their windows after midnight. They concluded that it was Lolo who had rapped on the glass—he knew it would force everyone back together. I grew up with the dead as present as the living. It was as if our dead family were in just the next room or traveling abroad. Sometimes they’d send you a postcard from their travels, a short and cryptic message to let you know they were thinking about you even though they were far away. Whenever we heard that a loved one had died, we asked for the time of death and recalled what we were doing when they passed. Our belief was that their soul roamed the earth for several days before moving on. Often, we would remember a strange phone call with no one on the other end, or a cryptic text message, or in my case, a single ladybug appearing on my beaker during chemistry lab in college and then flying away, leaving me with an overwhelming feeling of peace. I learned later that just before chem lab, my grandmother Inang had died.

It seemed like an idyllic place, living amongst loved ones, everyone helping each other. But soon, the membranes connecting the body of the family through daily life were ruptured.

*

My father came to the U.S. first, as a student, two years after President Marcos declared Martial Law. His plan was to study with some of the finest doctors and return to the Philippines as an American-trained eye surgeon. He was accepted to a U.S. medical residency program and anxiously awaited the paperwork from immigration. His start date at the American hospital came and went and still no visa, so he telegrammed the place, begging them to hold his spot. The hospital was well within its rights to give the residency to someone else, but they agreed to give him a few more days. If they hadn’t allowed him that one grace, who knows what would have happened?

My father is an optimist. With the deadline approaching, he proceeded as if the visa were a certainty and prepared for the move. He visited his dentist, who advised him to extract all of his natural teeth except the two healthiest ones. My father didn’t grow up with regular dental care or fluoride in his water. “It is better to lose your teeth in the Philippines,” his dentist said, “than all of your money in America.”

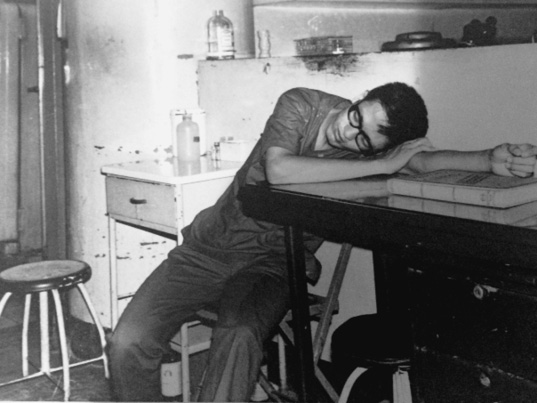

Grace’s father Totoy taking a study break as a medical student.

Grace before age 1 with older sister Tessie

at the family compound in Manila.

My father feared the pain of extraction, but he dreaded the unknown expense in the States more. He opened his mouth to the dentist’s pliers.

At the Chicago airport, a porter loaded his suitcase into the taxi. It was the first time my father had ever spoken to a Black man. My father tipped him a coin and the man stared at the silver in his palm before returning it. “Sir, I think you need this more than me,” he said.

A few weeks into his residency, my father sent for my mother Norma, my older sister Tessie, and me. He started moonlighting as a general physician at a prison on nights and weekends. We were supposed to stay for one year only, no big deal. But this is the danger of change: you never know what else will shift.

We planned to return home to Manila with the pasalubongs that my mother had been collecting for her family: plush towels and high-thread-count sheets from the clearance rack at Filene’s Basement and Jordan Marsh in downtown Boston. My father never thought he could make a life in the U.S., but he began to dream. Who could we become if we stayed?

In the meantime, my mother started working at the same hospital as my father. Although Norma had been trained as a radiologist, the researcher my father worked for hired her to work in his ophthalmology lab. Years later, after the researcher died, we found my mother’s name, Norma Talusan, listed as a co-author on the papers he published from their work. She gave birth to my younger sister Ann, a natural born U.S. citizen. My father decided to study for the exam for foreign medical-school graduates. He told himself that if he didn’t pass the first time, he wouldn’t try again. After spending every waking minute for months studying, he passed the exam, gained his medical license, and life was suddenly full of new opportunities. My father was made full-time at his job as a prison physician, with the promise of visa sponsorship from his employers. He waited one year and then two, but they never filed the paperwork. He was too afraid to ask why.

We survived our first New England winter. We moved to the suburbs of Boston, where my parents bought a house. My father left the prison to open his medical practice. My mother birthed two more U.S. citizens, Gerry and Jet. And before we knew it, one year had turned into five, and, in a blink, seventeen years passed without us ever returning home.

*

I lost my first name, Bubut, and later, even when I could hear the love in the voice of the person who had known me as a baby, I came to hate this name. Maybe in our language, it was beautiful, but in English, it sounded like an insult. I corrected them, reminding them that I was American now and only used my American name.

My first country disappeared as a place. I never heard it mentioned in the news and not too many people in my small town had heard of the place. They knew the neighbors, China and Taiwan, where toys and electronics were made. Their fathers and uncles who had served in the military knew Subic and Clark military bases and could say, Mahal kita. We were not an affectionate family during those difficult early years, so I did not know that they were parroting I love you, nor did I wonder who taught those men that phrase.

This is what happens when assimilation brings erasure: I lost my first language, Tagalog. My parents wanted us to embrace English only. They believed Americans would discriminate against us if they heard an accent in our voice. My parents still spoke to each other in Tagalog if they wanted to talk about us without moving out of earshot. We learned to listen closely when we heard our names popping from their otherwise indecipherable sentences. My mother told me that her parents did the same thing to her, except in Spanish, a language they continued to speak with pride, a marker of their class status and education, long after the colonizers had left.

Inside a few cells in my brain, I believe there’s a part of me that still knows Tagalog. I feel pain when I attempt to speak it, as though there is something I want to say desperately that can be expressed only in my first language. But I can’t access words, or that part of me that named the world first in Tagalog. When I hear strangers speaking Filipino languages, I am as drawn to them as kin.

*

We didn’t return to the family compound in Manila until twenty years had passed. When we finally went back, it looked as though our house had been through an earthquake. Everything was in ruins. Even the walls had caved in, so that what was once our home had now become a small room full of junk.

My father stood in the doorway and grabbed a piece of the rubble. It was a marble nameplate that used to sit on his desk in the medical practice he worked in before having to start all over again in the U.S., retraining as a resident and then re-taking the boards.

In the Philippines, people had heard of our names. We were known. On my father’s side, my uncle Dr. Tony Talusan had been a famous doctor on a long-running TV show about healthcare and the country’s poor. On my mother’s side, there were musicians, politicians, and businesspeople. We had a history and a context here. In America, we always had to correct people’s pronunciation.

My father handed the nameplate to me and said, “I’m giving this to you so that you can always remember my name.”

The marble was heavy in my hands, a miniature gravestone, and I traced the script with my finger, reading his name aloud. The afternoon light shone brightly on my father’s face. His hair was starting to gray. By this time in his life, some of his friends had already died. He was trying to tell me something, but I didn’t understand it at first. I wondered what kind of daughter he believed I was—one who could forget her own father’s name?

*

While we lived at the family compound, my father earned extra money by making artificial eyes. I’ve heard stories from my cousins who watched him make these eyes while they played in the shared courtyard.

Although it was only a sideline business, my father had become known as the best maker of cheap prosthetic eyes in the city. He could make all varieties of brown eyes and took pride in the process the way someone might enjoy cooking or any activity that transforms the mundane into the sublime. First, he would press the clay-like material into the eye molds until they dried. Then, he’d paint on an iris and pupil. Next, he’d place red threads across the white to mimic veins over a sclera. He’d finally place a sheet of plastic over each eye and drop them in the boiling water to melt together.

I can see my father leaning over a metal stockpot, his shirt hanging dangerously over the orange coils of the hot-plate burner, as he checks if the water is boiling. He chews on a red thread, the same thread that he uses to create veins. What does he dream this money will buy him? He stirs the pot, taking pride in the delicacy of the process. He thought it was beautiful, how the eyes bobbed and floated and rolled over—all those eyes that couldn’t see.