THE CATASTROPHIC COLLAPSE of the French Army and the British Expeditionary Force in the summer of 1940 led to the evacuation of British (and French) forces from Dunkirk, and this was coupled with the British Army’s massive loss of war material, especially heavier weaponry. The most serious losses were in heavy machine guns and artillery, especially anti-tank guns. The British Army’s 2-pounder anti-tank gun was a complicated and precision-made weapon and it would take time to make good the losses. In the meantime the Army would have to rely on extemporised anti-tank weapons such as obsolete artillery pieces and even the Molotov cocktail, a bottle filled with an inflammable liquid ignited by large matches attached to the sides of the bottle.

Hasty preparations were immediately put in hand for the country’s defence against invasion by sea and air: Britain now knew of Germany’s blitzkrieg tactics and could respond, albeit with very limited military assets. With Germany occupying most of western Europe, it was not known from which direction the enemy might come or where he might land. General Ironside, Commander-in-Chief Home Forces, had to produce a scheme to defend many hundreds of miles of coastline (the ‘coastal crust’), and to provide a substantial inland barrier (the GHQ Line), as well as mobile reserves behind the Line. In the event, the Germans would opt, in their planning for Sea Lion, for the shortest crossing route. The British Army Commands had also to consider a possible German occupation of the neutral Irish Republic with German diversionary attacks aimed at Ulster or, by air or sea, against the western side of Britain. Landings on the Scottish coast from occupied Norway had also to be considered.

A German view of Britain’s defences, mocking the use of children, who move a ‘knife rest’ whilst adults stand by. From the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung of 22 August 1940.

The fear of fifth columnists and paratrooper landings led, on 14 May 1940, to the formation of the Local Defence Volunteers, soon to be renamed the Home Guard. A covert branch of the Home Guard was also formed, the Auxiliary Units, trained to function as stay-behind cells operating from underground, camouflaged bases. Their role would be to harass an invader’s rear areas by sabotage and assassination. In addition, a parallel secret intelligence organisation was set up with a force of civilian spies in order to gather intelligence information. This information was to be passed by radio to army signal units, who were also located in underground hides. The organisation was known as the Auxiliary Units Special Duties Section. Some remains may still be seen: for example, the camouflaged signals base (Zero Station) on the top of Blorenge hill above Abergavenny in South Wales. The National Trust organises guided walks at Coleshill House, the headquarters of the Auxiliary Units, where an underground training hide, known as an operational base, may still be seen.

The threat of enemy invasion, whether real or imagined, led to the erection of many improvised roadblocks around the country, intended to hinder enemy movement and to act as posts to check identities, but these often proved obstructive to the movement of home forces and many were soon removed. The enemy’s innovative use of aircraft to land troops in order to capture airfields and other strategic or vulnerable points such as bridges led to a new threat coming from the sky: airfields now had to be protected against airborne landings, as well as against bombing and strafing attack. Areas where enemy gliders or transport aircraft might land were obstructed by poles and wires, or whatever was available – even by old cars and sewer pipes. Lakes and reservoirs had cables stretched across their water, and pillboxes were sited to prevent enemy seaplanes landing and disgorging troops. The signal that enemy forces had landed was the ringing of church bells in the vicinity: church bells were otherwise not heard for most of the war.

Anti-seaplane cable anchor point at Bosley reservoir, Cheshire. A pillbox also defended the reservoir.

On high ground at Minsmere, Suffolk, a ruined medieval chapel has been turned into a strongpoint, its interior filled by a concrete pillbox.

Around and behind the coast, fieldworks and concrete defences (pillboxes and gun houses) were built, minefields were laid (in June 1940, fifty thousand anti-tank mines had been issued), and many types of obstacle were installed or erected to prevent the enemy’s movement, especially of his tanks. Twelve armoured trains, manned by Polish soldiers, patrolled the coast from Cornwall to the Moray Firth. The defence of beaches and landing grounds by pillboxes and fieldworks had begun before the Second World War in Britain’s colony of Malta, against the rise of Mussolini’s Italy.

A row of anti-tank cubes at Aldeburgh in Suffolk, forming part of the coastal defences of this town, which also possessed an emergency battery. The battery observation post is located in the former windmill seen here.

In 1940 Defence Zones were established around the parts of Britain’s coasts deemed most vulnerable, with restricted access for civilians. Residents in the Zones were told to stay put in invasion occurred, to avoid roads being clogged with refugees, but this did not stop a gradual and large-scale migration from coastal areas in the early war years. Although a ‘scorched earth’ policy (the destruction of food supplies, petrol installations and vital public services and buildings so as to deny them to the enemy) was considered in the event of an invasion this idea was quickly dropped. To hinder an invader further, milestones and signposts were removed. Instructions were issued for the denial to an enemy of fuel supplies by immobilising machinery or by contamination. Also, any vehicles likely to fall into enemy hands were to be immobilised. Beaches were defended by pillboxes, barbed wire, minefields and, from 1941 onwards, anti-tank and anti-boat metal scaffolding.

A sight that might have been familiar had invasion occurred: a redundant aqueduct of the former Leominster Canal, crossing the River Teme stop line, Herefordshire, destroyed by a demolition charge in about 1941. It is not clear if this was part of anti-invasion measures or as part of a training exercise.

Inland, anti-tank stop lines were built, the principal one being the GHQ Line running inland along the southern and eastern sides of England, protecting approaches to London, with subsidiary stop lines built by Army Commands to give some protection to the vital ports and manufacturing regions such as the Midlands against the invader’s armoured thrusts. These lines, a key factor of the country’s defences in the summer of 1940, followed existing features wherever possible, such as canals, railway lines, rivers and also natural barriers such as the North Downs (GHQ Line). Where existing features were not available, anti-tank ditches were dug. Crossing points were defended by pillboxes and gun houses, with major towns and cities along the lines’ routes turned into anti-tank islands. It was hoped that these defences would delay the enemy long enough for precious reserves to be directed towards the threat. In effect, a battleground had been prepared.

The British Expeditionary Force already had experience of building anti-tank ditches and pillboxes in France during the winter of 1939–40. The anti-tank ditches were revetted with wood to present a sheer face to any tank encountering the obstacle. Ideally, both faces of the ditch would be reinforced so as to prevent a tank backing out of the ditch. In other locations riverbanks were similarly revetted. Important bridges were identified for demolition, the larger ones receiving demolition chambers in bridge supports, such as the railway bridge crossing the South Forty Foot Drain in Lincolnshire. At Sarre in Kent minor bridges were destined to receive pipe mines. It was realised that not every bridge could be destroyed: vital services such as telephone or electricity cables, gas mains and water supplies often ran across bridges, meaning that these should not be destroyed. And the possibility of British counterattacks against the invader had to be considered. Roads, bridges and airfield runways would be cratered by buried charges – if time allowed.

Concrete covers for anti-tank rails at Ellesmere, Shropshire.

Because the enemy’s intentions were not known, the defence posts along the lines had to have all-round defence. Where anti-tank obstacles of steel rails with concrete cylinders were sited, these had to be provided with hardened defences (pillboxes) or fieldworks for troops to prevent the obstacles’ removal. The surveying of the defence lines was carried out by Royal Engineer reconnaissance parties, sent by the Army Commands, which had previously identified suitable routes in their Command areas. It was intended that the lines and their defences would prove a barrier to the enemy’s general movement, especially that of his tanks and reconnaissance forces. Where the nature of the defence work was identified – be it pillbox, fieldworks, minefields or obstructed bridges – these would be marked on the ground and on a map referred to in the Royal Engineers’ report to the Command. Where bridges crossed the stop line, these were prepared for demolition, obstructed with steel rails or, where the surface of the bridge was suitable, mined. The anti-tank mine was a cheap and effective weapon. Large stocks were accumulated and used not only by the Army but also by the Home Guard: for example, Eastern Command (see the National Archives, reference WO 166/1193) anticipated that the Home Guard in the Cambridge area would acquire over ten thousand of these weapons by late 1941. The mines were not to be laid until the enemy was close.

One of a number of ceramic pipes, set in concrete, on a minor bridge on the Shropshire Union Canal, a 1940 stop line, at Audlem, Cheshire. It is possible that these were intended to hold either anti-tank mines or substantial vertical posts.

The steel-rail anti-tank barriers were, on the giving of the appropriate code word (various words were used to denote different states of emergency), ‘armed’ by slotting them into wooden-lined prepared sockets, gravel being packed around any gaps to prevent removal by the enemy. Instructions issued by Northern Command in late 1941 advised that vertical and bent (not welded) rails presented a satisfactory anti-tank barrier as long as the sockets were also lined with wood. To reinforce the barrier, concrete cylinders (they came in two sizes), in groups of three, were to be placed in front of the steel barrier to prevent the tank charging and breaking the rails. In some areas the cylinders had a central hole in which to insert a pole to enable their movement along the ground. Gaps at the side of the barrier would be closed by concrete ‘dragons’ teeth’ (also known as pimples) or anti-tank walls. The inland stop lines, it was hoped, would prevent the rapid progress of the enemy’s reconnaissance forces and delay and ‘corral’ the enemy’s tank and infantry forces, giving time for the reserves to be gathered together for an attack. However, some of the stop-line defences were futile given the shallowness of many of the watercourses chosen, especially during the summer months. A Southern Command report in July 1940 on a proposed stop line along the River Wylye in Wiltshire concluded that it could be breached with ease and, once breached, would render the rest of the line ‘useless’. Although many stop lines were proposed, it is clear that a significant number were, on surveying, found to have no tactical value and were abandoned; others were never fully developed. In June 1940 Army Commands were also preparing towns and cities for defence as anti-tank islands, but at that time resources were very thinly spread. London, in addition to its southerly protection by the GHQ Line, would eventually have three concentric rings of defences, with the central government area of Whitehall being one of three ‘keeps’, the others being at Maida Vale and the Tower of London. The vital port of Liverpool, in addition to defences ringing the city, had also to have defences on the Wirral to protect the approaches to the Mersey Tunnel.

Concrete anti-tank cylinders were often re-employed post war to reinforce, for example, the banks of water courses. These cylinders were cast with a central hole to enable them to be moved with a scaffold pole or bar.

Metal cover for an anti-tank rail socket at Apley, Shropshire: River Severn stop line.

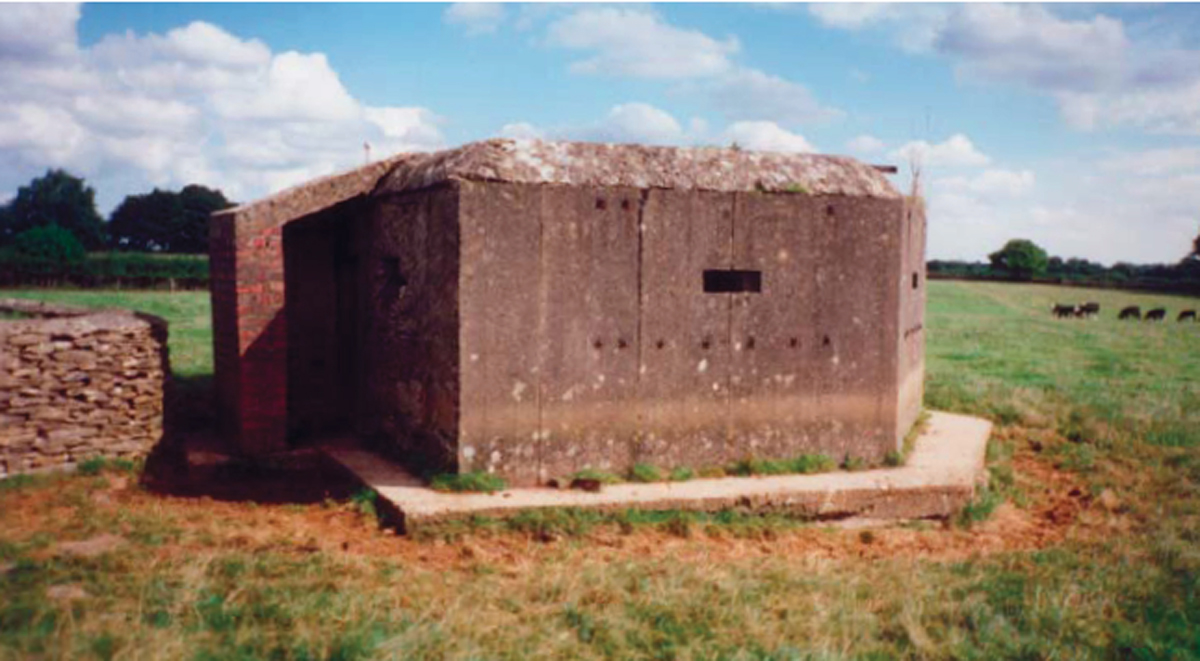

The pillboxes, designed to provide hardened fighting bases for the troops defending the stop lines and Vulnerable Points (VPs) such as airfields, were built in vast numbers in the space of a few summer months and were of a number of official and unofficial designs. Research carried out in connection with the Defence of Britain Project from 1995 onwards indicated that approximately 28,000 were built, of which a little short of 25 per cent survive. In May 1940, before France had fallen, a list of drawings was issued to Army Commands by the War Office Department FW3 (Fortifications and Works) of a range of pillbox designs for use in differing tactical situations. At the same time drawings were also issued for the design of the iron-rail anti-tank barriers, the bent-rail version (commonly known as the ‘hairpin’).

An FW3/22 pillbox on the Royal Military Canal in Kent. Created for defence in the Napoleonic era, the Canal was incorporated in 1940 into a stop line running between Hythe and Rye. Of interest are the steel-reinforced entrance blast wall and the textured finish, which would have received a coat of camouflage paint.

One of the principal designs of pillbox was the hexagonal FW3/22 infantry pillbox designed to accommodate up to five light machine-gunners (armed with Bren guns), together with one rifleman. It was to be built of reinforced concrete, with walls 12–15 inches thick, i.e. bulletproof. The huge loss of equipment in France, however, meant that the infantry rifle would have to replace the Bren in this and other designs. A larger design was numbered FW3/24; the most frequently built, this was an irregular hexagon, with a theoretical complement of five light machine gunners, two riflemen and a commander. FW3/23, a rectangular shape sometimes seen built into river or sea banks, had a rear portion accommodating an open light anti-aircraft position. Its complement was four men armed with three light machine guns and one rifle.

A pillbox of the FW3/22 design, a regular hexagon, at Wellingore airfield, Lincolnshire. Some of the reinforcing steelwork can be seen, and another, identical pillbox is visible in the distance.

Another design was the circular FW3/25, a variant being known by its manufacturer’s name of Armco (one of a number of contemporary commercial designs), where corrugated iron shuttering was used to create the circular design. Like FW3/24, the Armco appears to have been often used in coastal areas. Despite its small size, it was designed to accommodate three light machine gunners and one rifleman. Another circular and commercial design was the similarly diminutive Norcon, basically a pre-cast concrete tube with small loopholes, designed to be entered via its open roof (although roofed examples are known). Its concrete walls would not stop a rifle bullet, so it is likely that sandbags would have been placed around it to give added protection. Other commercial designs included the Allan Williams turret: a small steel (increasingly a vital strategic material) rotating turret for a light machine gun, seemingly designed for use in restricted locations or where tanks might not be expected. It did not offer protection against armour-piercing ammunition and a further disadvantage was that it used steel. Its employment was largely abandoned by the autumn of 1941.

An Allan Williams turret at Cley Next The Sea, Norfolk.

An FW3/25, a relatively rare circular design, forming part of the defences of the River Usk stop line, Bettws Newydd, Monmouthshire.

The most basic design was the FW3/26, a small square pillbox with three loopholes. Another design was the concrete, revolving Tett Turret. The largest pillbox designs were the FW3/27, with a central well for a light anti-aircraft machine gun, primarily used on airfields and radar sites, and FW3/28, to accommodate the 2-pounder anti-tank gun. A modified drawing, FW3/28a, was a design to accommodate two alternative positions for the gun. It should be noted that the FW3 drawings were prepared before the Army’s catastrophic loss of equipment at Dunkirk. The heaviest infantry weapon contained in the infantry pillbox was the Vickers machine gun, often positioned in specially designed pillboxes to cover vulnerable beaches with flanking fire. Other examples of this pillbox can be seen in Surrey (GHQ Reserve Line) and along the Taunton stop line. The lack of anti-tank artillery meant that the Boys anti-tank rifle, used by the Army, might also be used in pillboxes, although many of these cumbersome weapons had been left behind at Dunkirk.

A camouflaged pillbox, with an outer covering of local rock, built to contain a section of men near Beddgelert, protecting one of the passes of Snowdonia.

A coastal pillbox to the FW3/24 design at Tolman Point on the Isles of Scilly. The shuttering is of concrete blocks. The Isles were felt to be vulnerable and all landing places were protected.

A dual-purpose design, the large FW3/27 was designed to give all-round cover as well as light anti-aircraft protection. A central well, accessible from within the pillbox via the armoured door, contained the light anti-aircraft machine gun. In the top of the loophole (right) is part of the Turnbull machine-gun mounting.

The design of even the standard FW3 pillboxes varied from area to area: for example, some entrances were protected by an external blast wall, which might also contain a loophole. In the absence of the blast wall, one assumes a wall of sandbags was constructed to protect an entrance, this vulnerable feature being positioned facing away from the likely direction of attack. One or more small rifle slits in the entrance wall gave rear protection. Other pillboxes, such as the FW3/27 often seen on airfields, where all-round fire was considered absolutely necessary, were entered by low-level ‘creeps’. Different Commands had their own designs: Northern Command, for example, employed a lozenge-shaped design, examples of which can be seen in the Holderness area of Yorkshire and along the River Coquet stop line. Inside the majority of pillboxes would be an internal wall, often ‘T’- or ‘Y’-shaped, to support the roof and deflect blast, splinters or bullets ricocheting inside the pillbox.

Where pillboxes were built in what were considered to be primary strategic locations, these were often of a so-called ‘shellproof standard’, having walls at least 42 inches thick, as opposed to the bulletproof standard of 12–15 inches. The shellproof design was expected to be proof against tank and light artillery fire. There is evidence that some pillboxes not built to this standard were later strengthened with additional concrete skirts. Along Southern Command’s section of the anti-tank GHQ Line, for example, in July 1940 it was planned to have approximately six hundred shellproof pillboxes in place, with a much smaller number of the bulletproof design of pillbox. In addition, over two hundred of the 2-pounder anti-tank gun design – the FW3/28 and FW3/28a (with dual positions for the gun) – were planned. Because of materials shortages and changes in tactical thinking, initial plans were seldom fulfilled.

An FW3/28a pillbox with two alternative positions for a 2-pounder anti-tank gun above the Kennet and Avon Canal, part of the GHQ Line. Wootton Rivers, Wiltshire.

The construction of the pillboxes was carried out by Regular Army and Royal Engineer units, or by local civilian contractors, as little or no domestic building was now taking place. The effort required to build the country’s defences in the summer of 1940 was prodigious, with sixty-hour working weeks common. Fortunately, the summer was a good one. The earliest pillboxes were built of concrete poured into wooden shuttering containing steel reinforcing rods. As wood became scarcer following the lack of supplies from the Baltic countries, Britain’s main source of timber imports, brick or even corrugated iron formwork was used. As demand for concrete increased, some pillboxes were built of brick alone. A number of designs of prefabricated pillbox, using bolted concrete panels acting as permanent shuttering for a reinforced concrete shell, may also be seen, for example in Wiltshire along the section of the GHQ Line known as the Green Line. Another design seen, designed and manufactured by the Stent Company, used concrete bolted panels with the internal spaces gravel-filled; this may have been just bulletproof. An example has now been listed by English Heritage as it is within the curtilage of Dunstanburgh Castle in Northumberland.

A position for a flanking heavy machine gun at Weybourne, Norfolk. The brick shuttering is visible, as is the entrance blast wall.

A Stent prefabricated pillbox by Dunstanburgh Castle, Northumberland, a commercial design possibly based on the small, square FW3/26 design. This now has statutory protection.

A rare survival: a Norcon pillbox, basically a concrete pipe, open-topped and with a number of loopholes. This example formed part of the River Wye stop line at Bridge Sollars, Herefordshire.

It is important to note that the 1940 pillboxes were built for use by the Regular Army and not by the Home Guard, whose role at the time was seen as watching for the fall of enemy paratroopers, local defence and the general assistance of the soldiery in defending the country. As the Home Guard took over more responsibility for defensive operations after 1940, their local defence plans would sometimes include the use of the many thousands of pillboxes built around the country. Their use might be as originally intended, as a defence post, or as reinforced observation posts, or as decoys for drawing enemy fire.

A shellproof FW3/24 design pillbox, an irregular hexagon, at Avening, Gloucestershire, part of the GHQ Green Line, an extension of the main GHQ Line around Bristol. Here shuttering is of permanently attached bolted concrete panels.

Few, if any, of the large FW3/28 and FW3/28a pillboxes for the 2-pounder anti-tank gun may have been permanently armed because of the acute shortage of these anti-tank guns in 1940: it is likely that the precious guns would have been stored and rushed from a central location to any vulnerable spots once an invasion had commenced. It made little sense to locate these permanently in fixed positions. To make up for this shortage, numbers of Hotchkiss 6-pounder QF (quick-firing) guns, removed from tanks after the First World War, and firing solid shot, were used as emergency anti-tank guns. These were not mobile but had holdfasts (the vertical bolts set into a concrete base and on to which a gun was secured) and could be installed in strategic positions; here again, however, few positions would be permanently armed, the guns remaining in reserve ready for installation. These guns were protected by reinforced concrete gun houses of varying designs, including a version of FW3/28, giving lateral and overhead protection, with the gun’s original steel shield giving forward protection. A number of surviving positions have been found to be entirely open, consisting only of the holdfast mounted on a concrete plinth. These may have been designed to receive only sandbag protection. Other weapons available as temporary anti-tank guns included the French 75mm gun of First World War fame and the 18pdr field gun, of a similar vintage. All of these weapons were manned by the Army.

The Defence of Britain Project, launched in 1995, found that the FW3/22 design represented 27 per cent of pillboxes surveyed, the FW3/24 represented 40 per cent, the FW3/28 and 28a designs together made up 8 per cent, FW3/26 4 per cent, FW3/23 and FW/27 3 per cent each of the total with FW3/25 1 per cent, and with 14 per cent representing the many varied designs that were not FW3 varieties. In fact, many variations on the pillbox theme are to be seen around the country, reflecting variations in terrain and different Command and Royal Engineer preferences.

Much thought and effort were given to concealing the pillboxes, with artists and designers working out ingenious and appropriate camouflage schemes. Amongst these were men such as Oliver Messel, a stage designer. Various designs were employed and what we see today, standing in stark concrete relief, would have been disguised in many different ways during the war. According to a document held in The National Archives (reference WO166/4381), a stop line running through Staffordshire and Derbyshire, following the rivers Trent, Dove and Churnet, had its pillboxes variously camouflaged as: a haystack, a bridge pilaster, a woodman’s cottage, an outbuilding, a cowshed, a pile of alabaster, a mound of gravel, a kiosk, and (as at Rudyard Lake in Staffordshire) a boathouse. Materials as diverse as chicken wire, steel wool and proprietary stage scenery materials were used. Where such ingenuity was inappropriate, the pillbox might be painted in a disruptive camouflage pattern or draped in camouflage nets. Existing buildings, suitably reinforced, or even ancient ruins, also provided conveniently camouflaged locations for defence positions.

A position for a field gun covering a crossing of the River Dove at Ellastone in Derbyshire. This example shows two attempts at camouflage. It was built to resemble an agricultural building but has also received a green and brown disruptive camouflage finish.

The pillboxes did not stand in isolation: they were planned to be supported by minefields, barbed-wire entanglements and infantry slit trenches to prevent the enemy getting close enough to use grenades, heavier weapons or flamethrowers. Attempts were sometimes made to fit metal or asbestos covers over the vulnerable loopholes: if attacked by flame or smoke, the occupants were expected to don their gas respirators as protection against the fumes. Where possible, the defences along the stop lines were to be mutually supporting and sited to provide protection to both sides of the line. Nevertheless, the pillbox was, by late 1940 (especially after the appointment of General Alan Brooke as Commander-in-Chief Home Forces), seen as something of a death trap for its occupants and as running counter to the new doctrine of offence rather than defence.

In Northern Ireland defences were built along its borders with the Irish Republic as it was feared that Germany might invade the neutral south as a preliminary step to launching diversionary attacks on the western side of Britain. It should be noted that the Republic also built defences, against either a possible German attack or a preemptive takeover of the country by Britain.

Army Commands built bombproof headquarters so as to function under invasion conditions. Western Command, based in Chester, had one built under its headquarters; the four entrance shafts may still be seen by the side of the Dee. Plans were also made, should this base become unusable, to move to countryside locations. In 1940 major army formations also had battle headquarters, for example the 2nd London Division, part of III Corps, had one built below Whitney Court in Herefordshire, the Division’s role being to block a diversionary attack on South Wales from Ireland. Another battle headquarters was that of the then General Montgomery, in charge of XII Corps, who had a large underground headquarters at Tunbridge Wells in Kent.

Historically, Britain’s main naval bases had been protected in times of threat by coastal artillery batteries and underwater minefields. In 1940, in order to prevent enemy ships and transports reaching the many beaches and smaller harbours, emergency coastal artillery batteries had to be built with whatever guns were available. The heavier guns of 4-inch, 4.7-inch or 6-inch calibre were obtained from mainly naval stocks. Even 138mm ex-French naval guns were taken from interned warships and brought into use. By October 1940 over five hundred weapons had been mounted on ad hoc platforms, often lacking any form of protection. As the emergency slackened over the winter of 1940, more permanent, better shielded and reinforced concrete protection was given in the form of gun houses, magazines and shelters. The guns required battery observation posts (BOPs) to direct them and these were often lodged in existing buildings, such as in a windmill at Southwold in Suffolk. The batteries also required searchlights to scan the sea for possible night attacks, together with their own defences such as barbed-wire entanglements and pillboxes. Later, radar scanning equipment was added as a means of detecting the approach of hostile naval forces.

An unusual two-level pillbox at Lough Foyle, Northern Ireland. One level has loopholes to cover the adjacent road, the lower level covering the Lough against the landing of enemy seaplanes.

The weapons and troops of the country’s extensive Anti-Aircraft Command organisation would have been mobilised as a last measure; their powerful static or mobile 3.7-inch and 4.5-inch guns could be turned against an invader’s tanks. Instructions had been issued in the summer of 1940 that in the event of invasion the Royal Artillery units that operated heavy anti-aircraft and searchlight sites were to be involved in ground operations, using their rifles, and also the Lewis machine guns that they used for light anti-aircraft defence, to attack any air-landed troops. Again, in February 1941 further instructions were issued that, in anticipation of an invasion, each searchlight or anti-aircraft site was to become fortified with barbed wire, trenches and other perimeter defences, in order to add the anti-aircraft guns to the nation’s ground defence arsenal.

A small but well-preserved coastal battery for three 4-inch guns at Freiston in Lincolnshire. A holdfast for one of the guns is visible in the foreground.

As 1940 drew to a close, work carried on, albeit at a reduced level, with the continued digging or repair of anti-tank ditches, and the upgrading of beach and nodal-point defences. The year had passed without an invasion but there was every expectation that the country would face the threat again in 1941.

What is left now? Many pillboxes remain along the country’s coastline or close to the canals and rivers, a visible sign of the likely existence of a former stop-line status. Careful examination of old, un-resurfaced bridges, roads or even railway lines (a tank could travel along these) might reveal the concrete sockets for steel rails or mine positions (ceramic ‘mine pots’ for containing anti-tank mines). The concrete cylinders that were placed in front of the steel rails may also be seen lying close to their original locations, left over from the post-war tidying-up. Occasionally, indications of the original camouflage finishes applied to the pillboxes remain in the form of hooks for camouflage nets or the grass planted on their roofs to deter aerial observation, or even traces of camouflage paint. A more scarce survival might be a false roof forming an attempt to disguise the pillbox as a small building.