There are many familiar elements and compounds that are stable in the gaseous state under normal pressure and temperature conditions. Two that deserve special attention are oxygen and hydrogen.

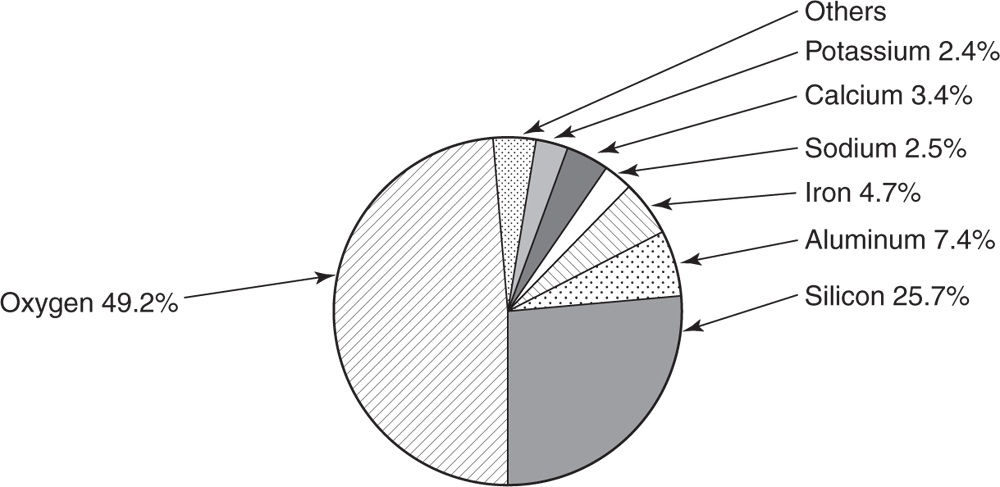

Of the gases that occur in the atmosphere, the most important one to us is oxygen. Although it makes up only approximately 21% of the atmosphere, by volume, the oxygen found on Earth is equal in weight to all the other elements combined. About 50% of Earth’s crust (including the waters on Earth, and the air surrounding it) is oxygen (see Figure 5.1).

The composition of air varies slightly from place to place because air is a mixture of gases. The composition by volume is approximately as follows: nitrogen, 78%; oxygen, 21%; argon, 1%. There are also small amounts of carbon dioxide, water vapor, and trace gases.

preparation of oxygen. In 1774, an English scientist named Joseph Priestley discovered oxygen by heating mercuric oxide in an enclosed container with a magnifying glass. That mercuric oxide decomposes into oxygen and mercury can be expressed in an equation: 2HgO → 2Hg + O2. After his discovery, Priestley visited one of the greatest of all scientists, Antoine Lavoisier, in Paris. As early as 1773 Lavoisier had carried on experiments concerning burning, and they had caused him to doubt the phlogiston theory (that a substance called phlogiston was released when a substance burned; the theory went through several modifications before it was finally abandoned). By 1775, Lavoisier had demonstrated the true nature of burning and called the resulting gas “oxygen.”

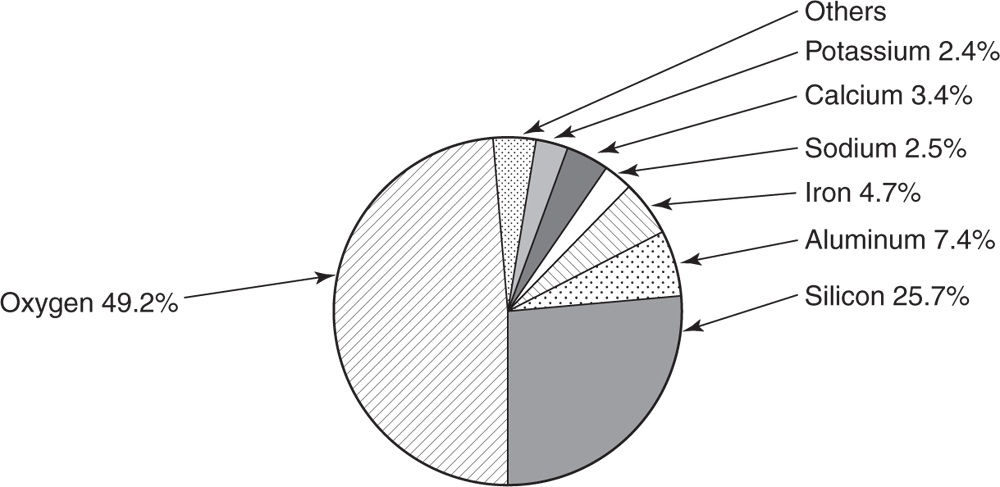

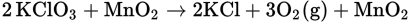

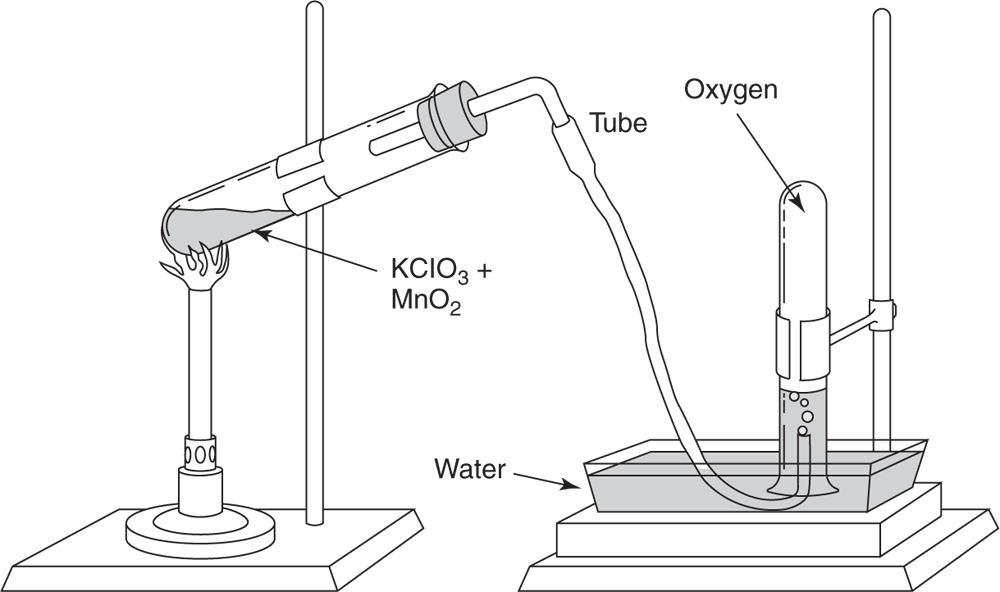

Today oxygen is usually prepared in the lab by heating an easily decomposed oxygen compound such as potassium chlorate (KClO3). The equation for this reaction is:

A possible laboratory setup is shown in Figure 5.2.

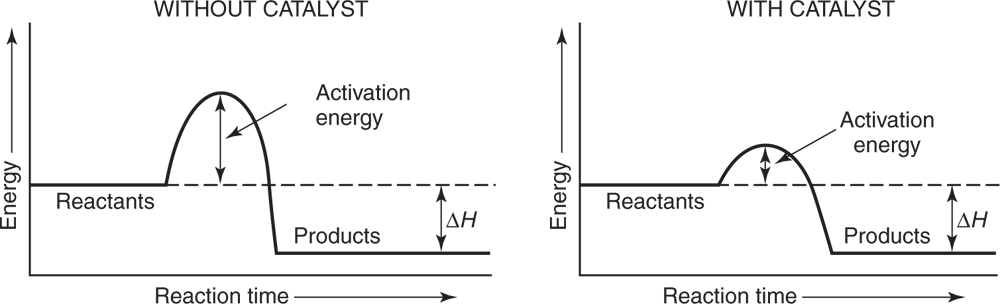

A catalyst speeds up the rate of reaction by lowering the activation energy needed for the reaction. A catalyst is not consumed.

In this preparation manganese dioxide (MnO2) is often used. This compound is not used up in the reaction and can be shown to have the same composition as it had before the reaction occurred. The only effect it has is that it lowers the temperature needed to decompose the KClO3, and thus speeds up the reaction. Substances that behave in this manner are referred to as catalysts. The mechanism by which a catalyst acts is not completely understood in all cases, but it is known that in some reactions the catalyst does change its structure temporarily. Its effect is shown graphically in the reaction graphs in Figure 5.3.

Graphic representation of how a catalyst lowers the required activation energy.

properties of oxygen. Oxygen is a gas under ordinary conditions of temperature and pressure, and it is a gas that is colorless, odorless, tasteless, and slightly heavier than air; all these physical properties are characteristic of this element. Oxygen is only slightly soluble in water, thus making it possible to collect the gas over water, as shown in Figure 5.2.

Although oxygen will support combustion, it will not burn. This is one of its chemical properties. The usual test for oxygen is to lower a glowing splint into the gas and see if the oxidation increases in its rate to reignite the splint. (Note: This is not the only gas that does this. N2O reacts the same.)

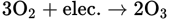

ozone. Ozone is another form of oxygen and contains three atoms in its molecular structure (O3). Since ordinary oxygen and ozone differ in energy content and form, they have slightly different properties. They are called allotropic forms of oxygen. Ozone occurs in small quantities in the upper layers of Earth’s atmosphere, and can be formed in the lower atmosphere, where high-voltage electricity in lightning passes through the air. This formation of ozone also occurs around machinery using high voltage. The reaction can be shown by this equation:

Because of its higher energy content, ozone is more reactive chemically than oxygen.

The ozone layer protects us from UV rays from the sun.

The ozone layer prevents harmful wavelengths of ultraviolet (UV) light from passing through Earth’s atmosphere. UV rays have been linked to biological consequences such as skin cancer.

preparation of hydrogen. Although there is evidence of the preparation of hydrogen before 1766, Henry Cavendish was the first person to recognize this gas as a separate substance. He observed that, whenever it burned, it produced water. Lavoisier named it hydrogen, which means “water former.”

Electrolysis of water, which is the process of passing an electric current through water to cause it to decompose, is one method of obtaining hydrogen. This is a widely used commercial method, as well as a laboratory method.

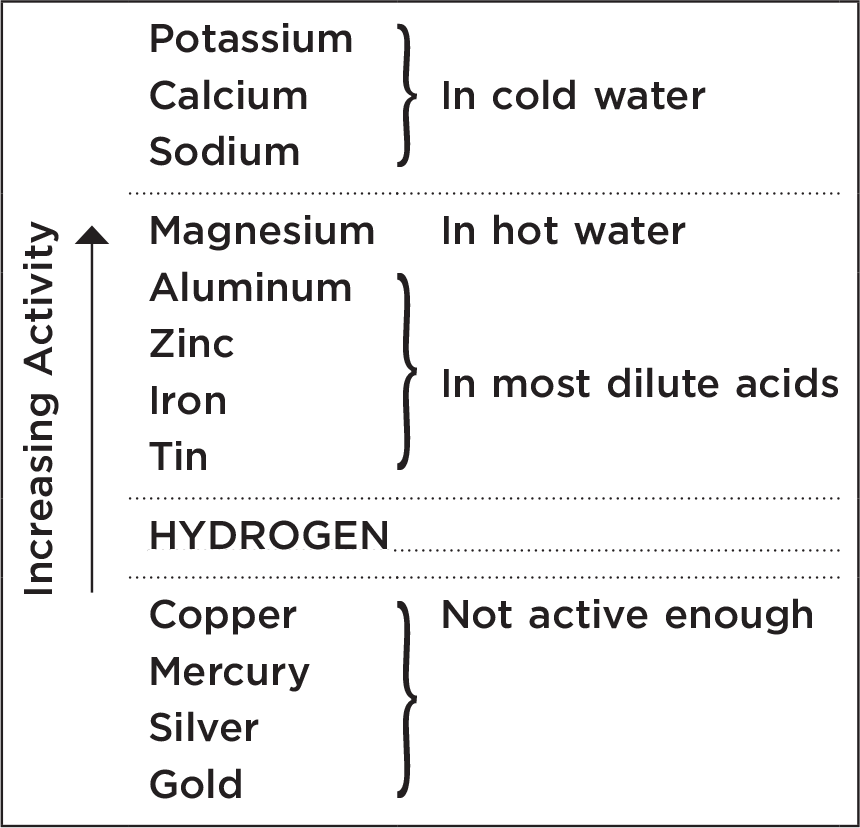

Another method of producing hydrogen is to displace it from the water molecule by using a metal. To choose the metal you must be familiar with its activity with respect to hydrogen. The activities of the common metals are shown in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1 Activity chart of metals compared to hydrogen

Know the relative activity of metals.

As noted in Table 5.1, any of the first three metals will react with cold water; the reaction is as follows:

Using sodium as an example:

With the metals that react more slowly, a dilute acid reaction is needed to produce hydrogen in sufficient quantities to collect in the laboratory. This general equation is:

An example:

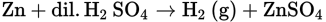

This equation shows the usual laboratory method of preparing hydrogen. Mossy zinc is used in a setup as shown in Figure 5.4. The acid is introduced down the thistle tube after the zinc is placed in the reacting bottle. In this sort of setup, you would not begin collecting the gas that bubbles out of the delivery tube for a few minutes so that the air in the system has a chance to be expelled and you can collect a rather pure volume of the gas generated.

In industry, hydrogen is produced by (1) the electrolysis of water, (2) passing steam over red-hot iron or through hot coke, or (3) by decomposing natural gas (mostly methane, CH4) with heat (CH4 + H2O → CO + 3H2).

properties of hydrogen. Hydrogen has the following important physical properties:

as dense as air.

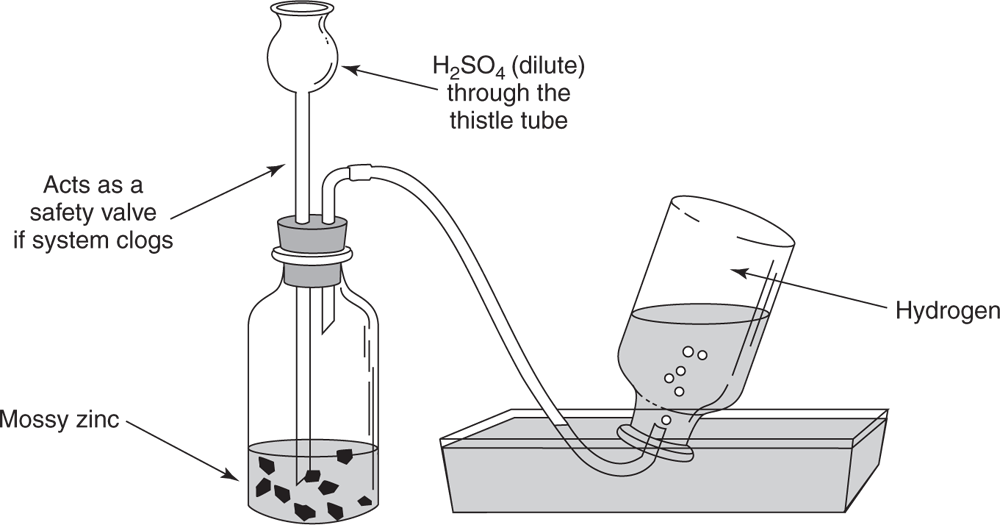

as dense as air.

Here the H2 in the beaker that is placed over the porous cup diffuses faster through the cup than the air can diffuse out. Consequently, there is a pressure buildup in the cup, which pushes the gas out through the water in the lower beaker.

The chemical properties of hydrogen are: