HISTORIANS

Before we get started, there are three people you need to meet.

Two of them created—through sweat, drudgery, obsession, near-pathological attention to detail and humorless dispositions—the definitive canon of Detroit history before 1900.

The third, my wild card pick, brings a needed dose of personality to any picture of the early city. And I like him. I kind of want to hug him.

I know it’s a little funny to start a book with the bibliography, and of course there have been dozens of other history writers and hundreds of other books. But almost everyone who writes about early Detroit starts with the same basic sources: Silas Farmer’s History of Detroit and Michigan and Clarence M. Burton’s Alexandria-like archive of original documents at the Detroit Public Library.

I’ll be quoting them so much that it just doesn’t seem polite to invite them to the party without proper introduction. So, here they are.

THE MAPMAKER

When Silas Farmer died suddenly in 1902, one obituary eulogized him as a particular breed of genius—the kind of person born with “the infinite capacity for taking pains.” It was a genius, the writer argued, that Silas Farmer had inherited from his father. But Silas’s genius was not the only thing his father passed down to him.

Silas Farmer, author of History of Detroit and Michigan. Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

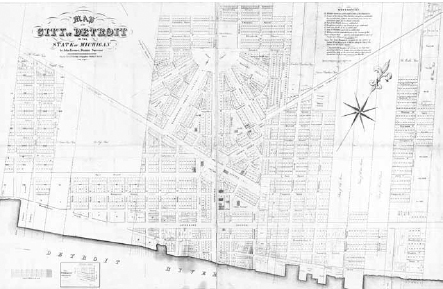

There was the family business, for one. Though he had been a teacher in Albany, New York, John Farmer came to Detroit as an entrepreneur—he wanted to make maps. A skilled surveyor and draftsman, Farmer had done some work for another publisher on contract, sketching out maps of the Michigan Territory from surveyors’ plats. But the subsequent pamphlets took forever to publish, and he didn’t get credit for his work in the final product. So John Farmer decided to strike out on his own. In 1825, Farmer’s own map of Michigan became the first published map of the territory.

John Farmer’s maps were exacting and lavishly detailed, and new arrivals to Detroit and Michigan snapped them up by the score. Bookstores stocked thousands of his pocket guides, and they were still hard to come by; before traveling into the wilds of the territory, new settlers would go door to door, looking for someone to sell them a secondhand copy. Farmer eventually taught himself how to engrave, cutting out a middleman in the publishing process. He was also a keen marketer, conducting direct mail campaigns and soliciting celebrity testimonials from political luminaries such as Lewis Cass and William Woodbridge.

John Farmer’s maps, like this one of Detroit in 1835, were the first and best maps available of the Michigan Territory. Map of the City of Detroit in the State of Michigan, 1835, by John Farmer, District Surveyor; Eng. by C.B. & J.R. Graham Lithographers, New York. Library of Congress Geography and Map Division.

Silas, born in Detroit in 1839, took an early interest in the business and took over completely in 1859 when John Farmer died unexpectedly at age sixty-one—of overwork, most people assumed.

“It seemed to me that the steam engine within him must sooner or later wear him out,” General Friend Palmer wrote of John Farmer. “And it did.”

Silas inherited that steam engine heart from his father. Whether it was the ethic of a workhorse that doesn’t quit until it drops dead or a genetic predisposition to heart problems, Silas died at nearly the same age, 63, and presumably of the same ailment.

In 1874, with business at the Farmer Company steady and successful, Silas decided to pursue a long-held curiosity. For the country’s centennial celebration, he would publish a comprehensive history of the city of Detroit.

Almost immediately, Silas knew that he was in over his head. But like the hundreds of researchers, writers and hobbyists who came after him, he did not give up. Instead, he got swept away.

It’s hard to express how grateful I feel for the work that Silas Farmer did. The nature of historical research was, obviously, completely different in Silas Farmer’s time, and while it is nice to just pop open my laptop and start downloading PDFs of his delightful neighborhood souvenirs from the Internet Archive, I’m not even talking about computers.

Silas had no Burton Collection (more on that in a minute) from which to draw. He sent form letters to churches, newspapers, businesses and government agencies across the Midwest and from San Francisco to New York City, Dublin and Paris soliciting records, account books and registries. He called on small-town historical societies, archives and libraries. He met with institutional Detroiters to pick their brains and rifle through their papers.

In his foreword to the first edition of History of Detroit and Michigan—published ten years after his research began and at a personal cost of about $17,000 (more than $400,000 today, adjusted for inflation)—he wrote of his research:

The tracing of some facts has been like the tracking of a hare; again and again it has been necessary to go back on the path, and renew the search, and at times, while rummaging in the garrets of old French houses and later dwellings, amid the dust and must of a century, I have almost forgotten to what age I belonged, and have for a time lived in the midst of past regimes.

History of Detroit and Michigan is, first and foremost, exhaustive. It’s about one thousand pages long and illustrated with hundreds of gorgeous Farmer Company engravings of houses, cityscapes, historic views and documents. It’s not a chronological history of Detroit from 1701 onward; instead, it’s a topical work, covering discrete subjects (military affairs, health systems, aldermanic wards and visits from famous people) in encyclopedic detail.

This is the history book of a mapmaker. The level of detail is painstaking—a list of public drinking fountains and the year they were erected, for instance, or a brief passage about “Old Joe,” the fire department’s Newfoundland dog—but every small, functional fact comes together to form a graceful picture of the whole. Silas wrote:

A good history is like a landscape, in that many things are brought at once within the range of vision; and it should resemble a photograph, preserving those minute points which give character to the subject…Stars of the first magnitude are easily found: It is the little asteroids that escape observation, and as these are discovered various planetary disturbances are explained.

The book was a success, selling thousands of copies around the world. Silas revised and reissued it in 1889 and again in 1894.

He lived a quiet and strictly Christian life. A founding member of the Detroit Young Men’s Christian Society and a board member at the Central Methodist Church for twenty-five years, Silas wrote poetry about temperance and living a morally upright life. And he worked and worked and worked, serving as city historiographer and writing pamphlets, gazetteers and street guides about Detroit, its surrounding communities and the state of Michigan. For An Illustrated History and Souvenir of Detroit, a little tour book, Silas counted the steps (two hundred of them) as he climbed to the top of Old City Hall to capture the breathtaking view.

Silas oversaw historical activities for the Detroit bicentennial festivities in 1901. A year later, he died in his sleep. His only child, Arthur, took over the Farmer Company, but he didn’t have his father’s gift for it, and he went out of business in a few years, granting all of the company’s engraving plates to Clarence M. Burton.

My copy of History of Detroit is a faithful 1969 reissue from Gale Research Company. Time after time—especially when I feel lazy—I crack it open and sit for a while with Silas, wandering the endless alleys and byways of his Detroit. Stern, puritanical Silas still manages to slip in a joke (like when he calls early citizen Peter Audrain “clerk of everything from time immemorial”) and a little romance (“The glory of the ancient market-days has departed. The black-eyed, olive-skinned maidens, in short petticoats, from the Canada shore, no longer bring ‘garden-sauce and greens,’ the French ponies amble not over our paved streets, and little brown-bodied carts no longer throng the marketplace”).

Like John Farmer’s maps before it, Silas’s History gave Detroiters a new opportunity to get intimately acquainted with their city. Nothing like it had ever been attempted before in the city; nothing like it since has ever been accomplished.

THE LIBRARIAN

Clarence Monroe Burton was born in Whiskey Diggings, a California gold rush town, in November 1853. His parents—Charles Seymour Burton, a doctor, and Annie Monroe Burton, a poet—had come to California in a wagon train from Battle Creek, Michigan, earlier that year. Whatever fortune they sought, they must not have found it, because they packed up and set out for home on the steamer Yankee Blade the following fall.

On October 1, lost in fog off the coast of Point Arguello, the Yankee Blade struck a rock. The boat broke in two. Annie Burton, with baby Clarence on her hip and pieces of gold sewn into her skirts, tried to jump from the ship into a waiting lifeboat. She missed her mark, and the two of them plunged into the rocky Pacific waters, but someone in the lifeboat grabbed Annie and pulled her and her son aboard.

Hundreds of passengers drowned when the Yankee Blade sank. All of the Burtons survived. By 1855, they were back in New York. These are auspicious beginnings for a man who would grow up to be—by most standards of polite society—kind of a bore.

Clarence M. Burton. Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

The Burton family returned to Michigan, to the farm town of Hastings (where Charles Burton started a newspaper, the Hastings Banner—still published today). Clarence Burton grew up, went to the University of Michigan, got in trouble with the dean for letting some circus animals loose on campus and graduated—though he refused to pay extra for the actual diploma—with a law degree.

Burton moved to Detroit in 1874 to clerk for a law firm. His wife, Harriet, and their firstborn, Agnes, stayed behind while he worked side jobs and slept in the office—he was only making about $100 a year. Still, he found spare change to snap up a book or two.

I’m not sure when Burton’s part-time history habit became a driving force in his life, but I imagine it happened slowly, book by book, document by document, mystery by slow-burning mystery. It’s a rewarding pursuit that way.

In 1885, Clarence, Harriet and their (now five) children moved from a small house in the neighborhood of Corktown to a slightly bigger house on Brainard Street off Cass Avenue, about a mile from the center of the city. The Burtons needed room for their growing brood, of course, and when Clarence Burton added a third story to the house, it was partly to gain a few more bedrooms for the children. But it also gave Burton a large study to call his own, as well as a space to store his growing collection of books.

His son Frank’s earliest memories were of the study and of his father’s exacting and methodical way of cultivating his library:

Up at a good hour in the morning, he ate a hearty breakfast and left at once for the office…Back for dinner at six after a good day’s work, he ate leisurely, talking with mother and the children about the happenings of the day and joining in with our jokes and guessing riddles. Dinner over, he spent a half hour idly over his coffee and then his rest period was done. He retired at once to his study and stayed until long after we children were in bed. Twelve to thirteen hours of hard, confining work each day, but it seemed to agree with him…

He never drank any liquor, and he spent no time in idle talk with companions. He never smoked, and neither drinking nor smoking were permitted in his house. He rarely visited others and very few visited him, because, I think, they realized that they were not welcome unless they came for a serious purpose and left when their errand was accomplished…He never played cards or other games except an occasional game of checkers with one of his sons, which he always won.

Everywhere, Clarence Burton’s life grew. His business grew: in 1891, he bought out the other partners at his law firm and organized the Burton Abstract and Title Company. He and Harriet had three more children. In 1892, he added a new wing to the house and hired a secretary to accommodate his books.

“It would seem now that he had room enough for any man’s books,” Frank Burton wrote, “but day by day boxes of books and manuscripts arrived, some from local sources, others from the East or from London.” A few years later, Burton built an addition to the addition to keep pace with his stuff.

Burton scoured rare book auction catalogues, corresponded with collections all over the world and trawled for the missing pieces of history that would fill in the gaps in his library. He found the papers of John Askin—a British merchant who came to Detroit in the 1760s—in an abandoned chicken coop and rode home sitting on top of them in the back of a horse cart. When he learned about a document with Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac’s signature on it, he signed a blank check and sent it to Montreal. He tracked down and interviewed elderly Detroiters, old-time residents and relatives of famous citizens, sometimes asking whether they had any musty old trunks of family papers in their cellars, attics or sheds.

He traveled when he could. In 1898, he made a cross-country trek “in the footsteps of Cadillac”—his singular biographical obsession—from Quebec City and Montreal to Bar Harbor and Nova Scotia. In 1904, he re-created a portion of Cadillac’s voyage on the French River in authentic birch-bark canoes. (Reportedly, Burton was not well suited to eating out of tins and sleeping on the ground.) And in 1907, he finally visited France as part of a grand tour of Europe, western Asia and North Africa. At St. Nicolas de la Grave—Cadillac’s reputed birthplace—the local archaeological society regaled Burton with tales from its sleepy medieval past.

When he couldn’t travel, he sent away for documents (such as the St. Nicolas de la Grave parish records) and had them transcribed and translated.

Personal tragedy only made him burrow deeper into the past. His wife, Harriet, died suddenly in 1896, leaving him to raise eight children alone. He remarried in 1897, but his second wife, Lina Shoemaker Grant, died less than a year later after contracting an infection during routine surgery. (This sad streak ended when he married his cousin, Anne Monroe Knox, in 1900. She brought four children from a previous marriage into the family, and they had one more child together.)

In 1913, Burton built a new house in Boston-Edison, leaving the Brainard Street house—and the colossal library inside of it—to the Detroit Public Library. Over the course of forty years, Burton had amassed thirty thousand books, forty thousand pamphlets and fifty thousand unpublished papers relating to Detroit, the Michigan Territory, the old Northwest, Canada and New France.

He continued to visit his library every day to research books, papers and presentations for the Michigan Pioneer and Historical Society, the Detroit Historical Society and the Michigan Historical Commission, all of which he chaired at some point. In 1922, he published his definitive multi-volume text, The City of Detroit, 1701–1922.

His masterwork, however, remains the Burton Collection, which was moved to the main branch of the Detroit Public Library on Woodward Avenue in 1921. The library sold Burton’s house on Brainard back to him; the library used the money to start an endowment fund for his collection.

The Burton Historical Collection is still at the main branch today, in a midcentury modern room built as part of the library’s 1963 addition. You still have to search by card catalogue. From the belly of the storage floors, archivists muster up two-hundred-year-old newspapers, boxes of letters in impeccable script, creaky scrapbooks and folders full of photographs.

Above it all, a portrait of Clarence Burton presides: mustachioed, wide-eyed, his aspect dead-serious. And while I’m not sure whether he would appreciate how much giggling I do there, I still say a silent “thank you” every time I visit.

THE GENERAL

I don’t remember how or when, exactly, I ran into General Friend Palmer for the first time, but my acquaintance with him and his city has been one of my most cherished.

I probably picked up his book, Early Days in Detroit, as an amusement—reminiscences of French damsels, horse carts, beaver hats and voyageurs, sketched vividly between passages about who married whom, which forgotten territorial soldier lived at what address or which general store burned down when. And my goodness—those rotten Indians and their barbarous ways.

It is a deeply imperfect history, and for at least one good reason: Palmer died the day before his appointment with his editors. Since Early Days is a book of recollections, they didn’t feel quite right making any changes without his say-so. Thus, “with a tender appreciation of Friend Palmer’s loveable and kindly characteristics, we present this book in its present crude but authentic form,” wrote his editors H.P. Hunt and C.M. June in 1906.

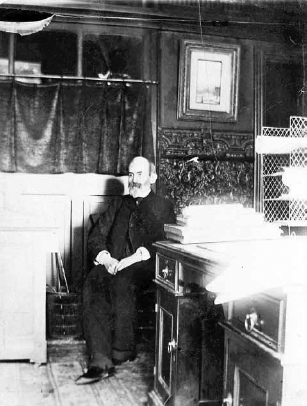

General Friend Palmer at the offices of the Detroit Free Press. Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

Some of the essays were written for newspapers and republished. Some were abridged versions of works submitted to the Pioneer Society or other historical digests. Other sections may have been written specifically for Early Days. So the book—over a thousand pages of it—is intact and unencumbered by shackles of chronology, narrative arc or consistent factual information.

It sounds like a disaster, perhaps not worth its real estate on the bookshelf. But what Palmer misses in his often wrong dates and sometimes repeated anecdotes, he more than makes up for in charm, wit and raw storytelling gusto. There are plenty of resources you can consult if you’re looking for names, dates and facts. But who else can give you memories of shopkeeper Peter Desnoyers, blue-eyed and hilarious, selling goose yokes to the bratty neighborhood kids? Or personal memories of Father Gabriel Richard’s sermons at St. Anne Catholic Church? Or casual accounts of stray, stubborn donkeys like this one:

The wide commons in the rear of the capitol were, during the summer months, covered in many places with a dense growth of weeds that grew almost as high as one’s head. On this common and through these weeds the horses and cattle roamed at will, and among them was a stubborn donkey, the property of Colonel D.C. McKinstry. This donkey was an especial pet of the boys, and many tried to ride him. He would allow them to get on his back and get comfortably seated; then he would start off at a canter, with a loud bray, up would go his heels and over his head would go the boy.

The Burton Collection is home to the general’s stiff, crumbly scrapbooks—a couple dozen of them. (Burton and the general were contemporaries; Early Days includes some corrections by Burton to Palmer’s historical articles. Palmer even writes once, on the topic of how Michigan came to be known as the Wolverine State: “I do not know for a certainty, but Clarence Burton does.”)

Inside the scrapbooks is a bright, funny and darling cross-section of the general’s delights: a page spread of articles about Napoleon; recipes for including more onions—nature’s health and longevity miracle—in your diet; tips for being a better husband and quotes about families that suggest Palmer’s affection for his own spouse, Harriet, and their children; and another page spread of foxy Victorian ladies suggesting that the general was also, well, a man.

Palmer was born in Canandaigua, New York, in 1820. He came to Detroit in 1827 with his mother—two days and two nights on a stagecoach from Canandaigua to Buffalo and then from Buffalo to Detroit across Lake Erie on the steamer Henry Clay. His father, also named Friend, had arrived three months earlier on urgent business for his chain of general stores, F&T Palmer, which he co-owned with his brother Thomas (with locations at Detroit, Canandaigua and Ashtabula, Ohio).

Tragically, the Palmer family would not be together for long; less than a month later, Friend Palmer Sr. died of pneumonia, which the younger Friend supposed he might have contracted after clearing his cellar of two feet of water in anticipation of the family’s arrival. “I was too young to realize our loss,” the general wrote.

In the winter of 1842, when Palmer was twenty-two years old, he left Detroit for Buffalo to work at a bookstore, where the owners also happened to be agents for the express service firm Pomeroy and Company—an early incarnation of American Express.

“It…necessitated my sleeping at the store,” he wrote, “as the express manager came in at midnight and I had to be on hand to receive him and take charge of the money packages, etc. For fear something might happen when the messenger and porter routed me out, the company provided me with a revolver, a six-shooter, the same as the messengers carried, a clumsy affair, though I never had occasion to use it.”

In 1846, he left the business to serve in the Mexican-American War. After that war, Palmer stayed in the military. During the Civil War, he served as assistant quartermaster general for the state of Michigan, was promoted after the war and held the office of quartermaster general until 1871, when he retired to business pursuits, writing and clerking at bookstores.

Palmer’s Detroit is in some ways unrecognizable. As a boy, he watched steamboats on the river and stood in the kingly presence of steamer captains like Walter Norton, who helmed the steamer that brought the general to Detroit:

A man of fine presence, and he used to cut a swell figure…clad in his blue coat, with its brass buttons; nankeen trousers, white vest, low shoes, white silk stockings, ruffled shirt, high hat, not forgetting the jingling watch chain and seals.

As a young man, he danced at all-night winter parties and walked French damsels home through the snow. He drove rickety horse carts through swampy streets. Sometimes the lynchpins came loose, toppling all of the carts’ passengers into the mud.

He lived through the mind-raking here-one-day, gone-the-next devastation wracked by two successive cholera outbreaks, the frightening and out-of-control grief of watching your friends, neighbors and prominent citizens hauled off in carts. After seeing a funny play at the theater, the general wrote:

The old sexton, Israel Noble, mounted on his horse and followed by half a dozen drays and carts, each one laden with dead bodies, warned us all to shut up the theatre and wait until a later day, when finally the cholera disappeared as suddenly and as strangely as it came.

But as lost to time as that time is, there are moments of harmony—kindred glimpses—that obliterate the narrow thoroughfares between here and now. Like the passage in Early Days in which the general snoops around in a dilapidated graveyard, making friends with the dead and looking for stories. Or the shiver of familiarity in some old black-and-white postcards of Belle Isle pasted in his scrapbooks. The island park looks largely the same today as it did in Palmer’s time, except for a few buildings repurposed or erased from the landscape. He must have pleasured there on hot summer afternoons, perhaps with Harriet and the girls. Maybe they took a buggy ride. He probably ran into friends.

Did the general ever sit at his desk, wondering forward into the future, where I sit on my front porch, or on the riverfront or at the library with a fragile scrapbook wondering back at him? When I find one of his notes in the margins of his scrapbooks—like the one where he crossed out an incorrect illustration that accompanied one of his articles and wrote, “No! this is Sheldon & Rood’s boosktore!” or the one next to a clip about the inner workings of a printing press (“I visited once.”)—it’s hard not to think, “Did he leave these notes for me?”