CAPTAINS OF INDUSTRY

What did Detroit make before it made cars? Lots of things: stoves, lumber, salt, ships, spirits, tobacco, pharmaceuticals and more, each product pushing Detroit’s pin on the map a little deeper, enticing a few more people to pack up their worldly belongings and head to the city to try something new.

Some were swindled and some just got by. But a few played their cards right—or were dealt winning hands to begin with—and walked away with a jackpot. A few of them even left Detroit in better shape than they found it. Others just left a good story to tell. It takes all kinds.

SILVER HEELS

You can meet Colonel David McKinstry in the painting First State Election in Michigan. He’s the one next to a huddle of newspaper reporters, wearing a tall beaver hat, holding a cane, his shirt collar unbuttoned. At his feet is a billet for his circus. His hair is gray, his aspect refined and his face firm, forward-looking and slightly smirking.

Colonel McKinstry (or was he a major—no one agrees) was Detroit’s amusement king. And like Ozymandias, his empire, though perhaps the most astounding of its time, has disappeared.

Look on his works, ye mighty, and despair: the colonel built the entertainment epicenter of early Detroit. Michigan Garden was opened in 1834, its four acres arrayed with fruit trees and flowers from all over the world. Its wandering walkways were brilliantly lit at night and filled with floats of music from the house band and the sound of dishes clattering in the Garden’s restaurant.

Attached to the Garden was a small menagerie, which included such suspect attractions as this event, advertised in an 1835 paper:

Rare sport at the Michigan Garden! Two bears and one wild goose will be set up to be shot at, or chased by dogs, on Tuesday, 20th October, at two o’clock P.M.

N.B.—Safe and pleasant seats will be in readiness for Ladies and Gentlemen.

The colonel also operated a theater, a circus and a museum, among the first in Detroit, “consisting of some of the finest specimens of ornithology, minerals, coins, natural and artificial curiosities, and a Grand Cosmorama occupying one building of the Garden, another containing thirty-seven wax figures of some of the most interesting characters.”

The museum was not the only first of its kind McKinstry brought to Detroit. He was also responsible for the city’s first bathtubs—an elegant and commodious addition to hygienic life in the old city. Before the public bathhouse at the Garden, you would have bathed once a week in the wooden washtub you used at home for your laundry, your dishes and scrubbing your floor.

Besides his business endeavors in botany, bathing technology, zoology, curiosities and traveling vaudeville shows, McKinstry was involved in a number of city- and state-building enterprises, serving variously as captain of Fire Engine Company No. 1, inspector of the port, city alderman, superintendent of the poor and on contract for the construction of the territorial capitol and the Saginaw Road.

Are you impressed yet? If not, consider the Olive Branch, his horse-boat to Canada, propelled through the waters of the Detroit River by two French ponies walking in place on tread wheels that turned beneath their hooves to power the paddle wheel on the side of the boat. (One writer described it as looking like “sort of a cheese box on a raft.”) The Olive Branch was launched from McKinstry’s wharf in 1825, ferrying travelers and their wagons, horses and cattle from shore to shore for the next five years.

McKinstry’s many and varied business pursuits—which in his later life included stagecoach lines, bigger and better river steamers and investment in the emerging railroad economy—must have been lucrative. The business advantage, personal presence and minor fortune he amassed in Detroit earned him the nickname “Silver Heels.”

McKinstry bootstrapped that gleaming reputation. When he came to Detroit from Hudson, New York, in 1815, he didn’t have any money or a bankable trade. But he was a hard worker and an ambitious guy, and it didn’t take long for him to make a name for himself in the small, scrappy harbor town. Detroit, after all, tended to reward the resourceful, the flinty and the fearlessly industrious. In a letter to a friend dated September 11, 1840, former territorial governor William Woodbridge recommended McKinstry as “a man of very considerable shrewdness and business talents—of much energy of character—quite disposed to speculation and not over scrupulous of means.”

The colonel’s museum, his wood-frame circus, his theater and most of his other entertainment properties burned down in a disastrous New Year’s Day fire in 1842. Not long afterward, he invested in some land in Ypsilanti, thirty miles west of the city, and eventually moved into the hotel he built there. Woodbridge speculated that the colonel may have fallen out with some of his business partners and perhaps—just perhaps—might have been “of doubtful capacity” to meet his financial obligations.

He died in 1856. He was seventy-eight years old.

THE GHOST

Daniel Scotten was thirty-four years old and working as a bookbinder in Palmyra, New York, when he decided it was time for a change. He took all the cash he had—about $1,500—and got on a boat. Not long after he landed in Detroit, his money was tied up in the industry he’d deemed most likely to grow: tobacco.

Scotten’s wager was either lucky or shrewd, as in the next several decades, Detroit became a tobacco boomtown, and by 1891, it was the city’s leading industry. Splendid quantities of the stuff grew in southern Ontario, and it was cheap to import. As Detroit had yet to become a union town, costs for labor were low, too.

Tobacco boomed in Detroit during the late 1800s. An 1884 advertisement for American Eagle Tobacco shows a portrait of actress and celebrity spokeswoman Lily Langtry dressed as a geisha. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZC2-5739.

The same year he arrived, Scotten established a partnership with Thomas C. Miller and cofounded Thomas C. Miller & Company Tobacco. Three years later, Scotten sold his share to Miller, bought out another tobacco firm, wrangled some partners and founded Scotten, Granger & Lovett. Years passed, partnerships shuffled, business boomed and Scotten eventually built a huge factory on Fort Street to house the Scotten & Company manufacturing operations—makers of Hiawatha Tobacco.

Hiawatha was one of several leading brands of Detroit cigars, cigarettes and chew: others included Globe, American Eagle, Banner and Mayflower, helmed by future Michigan governor John Judson Bagley.

Detroit tobacco made Scotten an outrageously wealthy man, and as some outrageously wealthy men sometimes do, Scotten reinvested his wealth into real estate, making him even more outrageously wealthy. His most prominent property was the glamorous and cosmopolitan Hotel Cadillac on tony Washington Avenue. Every week, Scotten drove his carriage, hauled by two white horses, to collect rent at the hotel, usually stopping at the bar to enjoy a drink from a “special” bottle kept behind the counter just for him. He also owned seven thousand acres of farmland and 1,800 head of cattle in Petite Cote, Ontario.

At his own home in Detroit, he raised hens and turkeys, which he gave away to friends (including Clarence M. Burton—maybe to gain the favor of posterity?) and strangers as holiday gifts. Another distinctive sight in the Scotten backyard was a towering pile of lumber, a help-yourself stash for anyone who was suffering the tough winter months without fuel for warmth.

Does it sound like Scotten was a little eccentric? It’s not your imagination. Detroiters admired and respected “Uncle” Daniel Scotten—the classic mold of a self-made man and a genuinely charitable person who not only doled out massive cash gifts to worthy institutions but also personally distributed clothing and food to those in need.

They also thought he was kind of a nut. Alarmingly well read, Scotten kept thousands of books in his home library, loved Shakespeare, studied anatomy, literally read the dictionary for fun and visited his local florist just to argue about the Latin names of the weeds in his garden.

“For a man who has a number of millions of dollars, Daniel Scotten lives the life of a hermit and works like a horse,” wrote the Detroit News-Tribune in an 1896 profile. Scotten was nearly seventy-seven years old. “He speaks business in words of one syllable, such as: I will, I will not, yes, no, all right, good day.”

Oren Scotten, Daniel Scotten’s nephew, was born in New York in 1850 and came to Detroit when he was sixteen. Naturally, he asked his magnate uncle for a job. Allegedly, Scotten said, “Take off your coat and work, then.” And Oren, not sure what else to do, picked up a broom and started sweeping the floor. Oren’s humble start at Hiawatha eventually led to a partnership with his uncle.

In 1898, when Daniel Scotten was a spry eighty years old, Oren became an incorporating member of the Continental Tobacco Company, a holding company whose shares were mostly owned by American Tobacco. The Scotten Company became the “Northwest Branch” of Continental Tobacco, and Daniel Scotten retired to the tune of $2.5 million (a staggering $64 million today).

In 1899, Daniel Scotten died of “extreme age,” according to his obituary in the New York Times. But the old millionaire’s soul would not rest, legend said, until his factory, which was temporarily closed shortly after his death, was blazing again. Wrote Stephen Bromley McCracken:

At one time two servants employed at the former dwelling were passing through the roadway to Porter street, when the figure of a man, white and terrible, came out from behind the barn. To their excited imaginations it appeared to be the ghost of Daniel Scotten, but on his face was a scowl as he turned and gazed at the chimneys of the disused factory. With loud screams the servants made tracks for the street and notified patrolman Purcell, who examined the grounds, but could find no ghost. Since then it is claimed that the wraith appeared several times. It is even rumored that he has been heard to say, Ever more must I walk until the smoke comes out of the chimneys of the old plant. Superstitious neighbors remember that Mr. Scotten used to make nocturnal trips about the house grounds with a lantern to see that all the doors were properly closed and the watchmen attending to their duties…Anyway, since the works have been reopened, it be said, as Hamlet said to his father’s ghost, Rest, rest, perturbed spirit.

As for Daniel Scotten—in life—he preferred to be remembered by his good works alone. For his obituary in the Detroit Journal on March 4, 1899, a close friend is reported to have said:

Detroit doesn’t need any fountain, or monument, or memorial building to keep Uncle Daniel in its hearts…Several generations of people will have to pass away before your Uncle Daniel will be forgotten. And Detroit doesn’t want, in the future, to have the mannish woman or womanish man raise an eye-glass towards a monument and exclaim: Ah! What is that! Who was he!—Oh, some rich old duffer who died a few generations ago…Daniel Scotten should be paid the tribute of having nothing erected to his memory by the present generation.

THE CLOCKMAKER

Felix Meier sailed to the United States from Germany in 1864. It was a grueling journey: the boat was crowded, food supplies were perilously low and Meier’s wife was pregnant. She gave birth to their son, Louis, on board the ship.

Meier was a stonemason by trade, and when he arrived in the United States he worked on railroad bridges. He briefly moved to Chicago in 1871 to rebuild after the fire that leveled the city that year.

Stonecutting was a respectable trade, but the level of craftsmanship was considered to be somewhat rough. Not bad for a day job, but Meier had finer dreams. In the evenings, as a hobby, he made watches and clocks. And one Sunday, while napping on a davenport, Meier dreamed of his masterpiece: the American National Astronomical Clock.

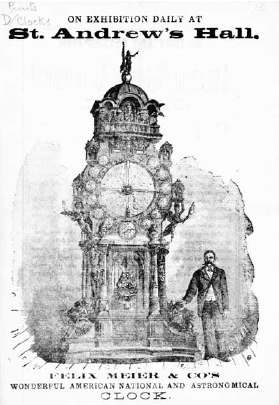

Felix Meier’s American National Astronomical Clock, date and original publication unknown. Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

He started to build it about 1870, and it took him ten years to complete. When it was finished, it was a baroque wonder: eighteen feet tall, four thousand pounds, intricately carved from black walnut, its machinery demandingly precise.

At the top of the clock was a marble canopy. Atop the canopy, a gilded statue of Columbia. Beneath the canopy, the seated figure of George Washington. Adorning the four corners of the clock were the phases of life, each of which marked a quarter hour with a distinct bell: the infant, the youth, the middle-aged man and the old man. In the center of the clock was the figure of a skeleton, which struck the hours with “a deep, sad, tone.” And then (according to Silas Farmer):

When Death strikes the hour, a music-box concealed within the clock begins to play; the figure of Washington rises slowly from his chair and extends the right hand, presenting the Declaration of Independence; the door on the left is opened by the servant, and all the presidents from Washington to Hayes enter in procession, dressed each in the costume of his time. Passing before Washington, they raise their hands as they approach him, walk across the platform, and disappear through the opposite door, which is promptly closed by the second servant. Washington then resumes his chair, and all is again quiet, save the measured tick of the huge pendulum.

Meier’s great clock was also a marvel of astronomical clock-making; some enthusiasts considered it one of the most accomplished astronomical clocks ever made.

It told local time, as well as time in nineteen major world cities from Paris to Peking, Cairo to Constantinople. It indicated the house of the zodiac, the revolutions of the earth on its axis, the revolutions of the moon around the earth, the phases of the moon and the movement of the planets around the sun. (“There is, therefore,” one reporter wrote breathlessly, “a movement in this wonderful piece which cannot regularly be completed more than once in 84 years!”—because Uranus takes eighty-four years to orbit the sun.) Meier’s calculations were so precise, he claimed, that they would be accurate for two hundred years.

The clock went on a yearlong U.S. tour. By the time the tour was over, the clock still worked, but Meier was broke. Shipping the enormous clock around the country had eaten into the profits from the tour. It was also rumored that Meier was a gambler. Debt-mired, he was anxious to sell the clock to the highest bidder.

What became of Meier’s American National Astronomical Clock—“undoubtedly the most famous clock ever constructed,” wrote one biographer—is unclear.

In 1880, Meier sold his share of the clock for $1,000 to Jennie Babcock of New York City. Clarence M. Burton reported that the clock was displayed in the Tiffany’s showroom for twenty-five years. But that’s impossible. In 1895, Meier received a letter from Eliza Thayer, who told him that Mrs. Babcock had passed away, and although she had found some interested buyers for the clock, the offers were low and the clock was in storage—dusty, defaced and in need of repair.

“I long to see this wonder,” Thayer wrote, “where it can be observed and known. Can your services be obtained to restore it to running order, either as it is placed in New York City or in Washington?”

Meier wrote back and asked for the lowest price at which she would sell, as well as the percentage she would offer him as commission were he able to secure a buyer. Negotiations with Ms. Thayer fell through. In 1907, a year before he died, Meier’s astonishing astronomical clock was destroyed in a New York City warehouse fire.

But it was not the end of the Meier clock dynasty. Felix’s children turned out to be just as ingenious. His son Felix Jr., at nineteen years old, perfected a compact steam engine that he mounted on a buggy and drove around the streets of Detroit during the early days of the automotive era. His son Andrew, at twenty, invented a carpet-cleaning machine. Both Felix Jr. and Andrew died young, but Felix’s son Louis would send the Meier name into the new century.

Louis built his own astronomical clock—Louis Meier’s Wonderful Clock, a similarly astounding work of craftsmanship: fifteen feet high and seven feet wide, with a twelve-inch globe that revolves on its axis every twenty-four hours. Father Time strikes a chime at the top of the hour. He completed it in 1904; it was exhibited at the Michigan State Fair in 1906, and by all accounts, the clock demonstrated the continued vitality of the Meier clock brand. Louis Meier went on to open a small jewelry, watch and clock shop in 1914. By the 1930s, Meier and Sons was manufacturing commercial gears, and the company produced arsenal components during World War II.

Louis Meier’s Wonderful Clock met a much kinder fate than his father’s invention: it’s on display and remains in full working order at the Detroit Historical Museum.

DAUGHTER OF INDUSTRY

Eber Brock Ward began his career as a cabin boy on a Great Lakes schooner in the employ of his uncle Captain Samuel Ward. He was thirteen years old. When he died, he was one of the richest men in the Midwest.

He came to Detroit in 1821, when it was still a rough-and-tumble port town of about 1,400 people. Great Lakes ships were pretty small then, and most of them were British-owned. None was owned by Detroiters.

He bought his first share in a steamboat—the General Harrison—in 1835, when he was twenty-four years old. By the mid-nineteenth century, Captain Eber B. Ward and his uncle, Captain Sam, had a fleet of thirty ships and were the largest shipowners on the Great Lakes.

As industrial enterprise expanded in Detroit and Michigan, Eber Ward was involved with everything. Lumber? He owned seventy thousand acres in northern Michigan and built his own sawmill—the finest in the country. Steel? He started the Eureka Iron and Steel Company in 1853. It was the first American firm to use the fast, inexpensive Bessemer process to make commercial steel. Railroads? As president of the Pere Marquette Railway in 1860, Ward lifted the struggling company out of bankruptcy and dysfunction. His lumber and metal were used for making new railroads. He opened a steel mill in Illinois and another in Milwaukee. He built a lumber mill in Toledo. He built a shipyard in Wyandotte, Michigan. He started a plate glass company. He bought a few newspapers. He bought a salt mine and a silver mine. And in 1875, while he was walking down Griswold Street, he had a stroke and dropped dead.

Captain Ward’s death stunned the region. “His immense wealth and business interests were such that hardly a city of any importance in the Northwest but will be more or less affected by his death,” wrote the Western Historical Company in History of St. Clair County, Michigan. “His enterprises extended through a number of states reaching from the cold and icy northern shores of Lake Superior to the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico.”

At his death, the total value of his estate—dizzyingly entangled in a vast array of accounts, companies and properties—was tough to guess, but $10 million is probably fair. (That’s close to $200 million, adjusted for inflation, based on the 2010 consumer price index.)

He also left behind an expansive family—a wife, an ex-wife and seven children. His youngest, Clara, was just two years old. She inherited a significant chunk of her father’s lumber interests and grew up, predictably, in luxury. She moved with her family to New York, attended private school in London and as a teenager made an aristocrat-hunting tour of southern Europe with her mother, Eber Ward’s second wife and widow, Catherine Lyon.

In 1890, a Belgian prince and diplomat, Marie Joseph Anatole Pierre Alphonse de Riquet, Prince de Caraman-Chimay, proposed to Clara Ward. She was seventeen years old when they were married in Paris.

The Prince de Chimay got the better end of the deal, at least at first. His title was real, but he didn’t have much in the way of royal fortunes. His chateau needed extensive repairs, and Clara spent $100,000 of her inheritance to pay off his debts. Belgians gossiped that King Leopold favored Clara Ward a little too keenly, and court society shunned her.

To escape the harsh talk, Clara and her prince moved to Paris, where they enjoyed the artistic, absinthe-tinted Belle Époque nightlife.

In 1896, in one of those jangly cafés, Clara met Rigó Jancsi, a swarthy Hungarian violinist with piercing eyes and dark, romantically unkempt hair. It was love at first sight, the tabloids reported to a frankly baffled public. Clara and her “gypsy” ran off together, scandalizing everyone and catapulting each other to instant celebrity. (The Prince de Chimay sought a divorce.) Tabloids tracked their every move. Rigó played salons and music halls across the continent, and Clara—inspired, perhaps, by her second husband’s art—performed at the Folies-Bergere, the Moulin Rouge and dozens of other cabarets. Her gimmick was the pose plastique—in a skintight, flesh-colored body suit, she struck a comely posture and then stood stone-still. Titillating, right?

Sultry Clara Ward postcards circulated Europe. Hungarians commemorated the scandalous romance by inventing a chocolate cream pastry called the Rigó Jancsi. Toulouse-Lautrec painted them when they appeared together at the theater.

While she was partying in Europe’s capital cities decked in diamonds and furs, gossip rags sniveled that she was bleeding millions, living only to serve her own selfish desires. I wonder if the truth was more complicated than that. She was all but disowned by her wealthy Detroit family, paying alimony to her children with the Prince of Chimay and fighting constantly with Rigó, who allegedly owed her hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Detroiters thought that their city had arrived when Europe’s bluebloods started poaching industrial heiresses for wives. With every princess crowned, an American fairy tale came true. But some happy endings faded into ennui, disappointment and drama. Martha Palms, the Countess de Champeaux, died young. Matilda Cass Ledyard, Lewis Cass’s granddaughter, married Baron Clemens von Ketteler, a German ambassador to China, who was gruesomely killed (his heart was ripped out and eaten) during the Boxer Rebellion after attacking and murdering, for no discernable reason, a young Chinese civilian.

I know some ladies (or their gold-digging moms and dads) went looking for this supposedly sweet setup, but can you imagine moving thousands of miles away from your family to a country where you don’t speak the language to shack up with some older man you barely know whose drafty palace hallways faintly smell of the collapse of European empire?

It’s hard to feel bad for Clara Ward, but I don’t think her life was easy. From her father, besides her millions, it seemed she had inherited a personal propensity for homefront disaster. Eber Ward’s first marriage ended in divorce after his wife accused him of serial adultery. His children from both wives were born with demons. His son Charles was “deranged and eccentric,” as well as bankrupt; Henry Ward was committed to a state mental institution; and Frederick Ward committed suicide.

Clara and Rigó divorced in 1904. Clara got married again, this time to Peppino Riccardi, an Italian travel agent. Riccardi accused her of having an affair, and they separated in 1911.

She was forty-three years old when she died at her villa in Padua, possibly of pneumonia. Though reports from Rome of her funeral stated that she was buried a pauper—her only asset a cheap case of jewels seized by creditors—the American consul at Venice wrote to relatives in the United States and assured them that Ms. Ward’s funeral was “elaborate and costly.” In a will drafted in 1904, Clara left an estate worth more than $1 million to Riccardi and her two children in Belgium.

Wrote the Detroit News in her obituary:

A score of years ago, Clara Ward was the idol of Detroit young womanhood. Wealthy and beautiful, she left her native Detroit to marry the Prince de Chimay and Caraman, a Belgian nobleman closely allied to the royal family. Her light burned brightly in the capitals of Europe. She was favored of kings, the leading figure in many startling escapades, the toast of Paris. She was a princess, an American princess, who had captured the old world by her wit and her daring as much as by her lovely face.

Today she lies dead in her home in Padua, Italy—a prodigal daughter spurned by her mother, shunned by her former companions, her life ended, if not in poverty, at least in unlovely circumstances. She died a woman without illusions.