RIVALRIES

When Detroit Republicans decided that they needed a businessman in office in 1889—someone mild, broadly appealing and sensitive to their landed interests—they nominated fifty-year-old gentle giant Hazen Stuart Pingree. Pingree, a Civil War veteran who had been captured by Confederate forces at the Battle of North Anna in 1864, wasn’t a political person. But his reverence for President Abraham Lincoln, and the values Lincoln outlined in his address at Gettysburg, inspired Pingree to join the Michigan Republican Club.

His shoe company—started small in 1866 with $1,500, used machinery and eight employees—had grown into a huge operation, grossing upward of $ 1 million a year. It made Pingree a wealthy man. Their wealthy man, Detroit Republicans wagered. They wagered wrong.

When Pingree promised to root out corruption in city contracts and initiate widespread municipal reforms, he wasn’t paying lip service to disenchanted Democrats. Pingree was for real. After his landslide election to office, he wasted no time.

Within weeks, wheels were in motion. He announced a sweeping plan to repave Detroit’s rancid cedar block streets and improve street cleaning. He fought to correct unfairly low tax assessments on high-value property owned by holding companies. And he began a decades-long battle to secure fair play and reasonable rates for public services; Detroiters paid nearly double the rate for their gas and electricity as residents of other cities in Michigan and the Midwest.

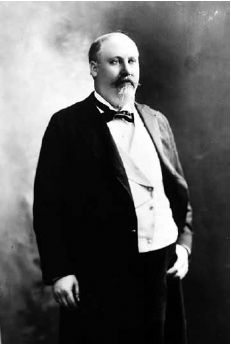

Hazen S. Pingree, circa 1900. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection, reproduction no. LC-D4-40050.

He made enemies everywhere. The Republican Party and members of the business community felt betrayed. Newspapers ignored him. Banks refused to work with him. Old friends stopped talking to him. But the people adored him, and the angrier he made corporate interests, the more they showered him with love.

STREET FIGHTERS

In the same election that made Pingree mayor, fellow Civil War veteran James Vernor was elected to the Detroit Common Council.

As a pharmacy clerk, Vernor had tinkered with a ginger ale recipe on the side. But it just wasn’t coming together, so when he enlisted to serve in the Union army in 1862, he dumped his experiment into a wooden cask for safekeeping. He returned home to a lucrative surprise: the barrelaged soda base had just the right balance of mellow, sweet and spicy. Vernor’s—the oldest still-produced soda in the country—was born.

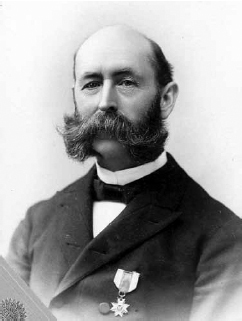

James Vernor Sr., circa 1885. C.M. Hayes & Company. Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

That’s how Vernor liked to tell the story, anyway. While there’s no proof of the happy accident that gave the world Vernor’s barrelaged ginger ale, it was, of course, true that Vernor enlisted—he was a member of the Fourth Michigan Cavalry, the unit that captured Confederate president Jefferson Davis at Irwinville, Georgia, in May 1865. Vernor kept a dressing gown and a gold piece that had belonged to Davis as souvenirs.

Like Pingree, Vernor was briefly a prisoner of war, but he escaped his captors and hid in an abandoned house for three days while the Union army drove Confederates out of Murfreesboro, Tennessee.

Vernor, too, went into business when he returned from the war, opening a pharmacy and soda shop on Woodward Avenue in 1866—the same year that Pingree started his shoe company. And like Pingree, Vernor’s enterprising spirit made him rich.

In 1889, Detroit streetcars were still pulled by horses and heated by smelly stoves, their carriage floors covered with straw. Most cities of Detroit’s size had long since electrified their rail lines. The streetcars paid no property taxes to the city for the privilege of running their services on its streets. They were supposed to pay 1 percent of gross revenue instead, but they refused to let the city inspect the books and paid whatever they felt appropriate.

Vernor had spent years standing in the doorway of his drugstore, greeting his neighbors and customers, tipping his hat to passersby and watching horses—so many horses!—hauling taxis, grocery stands and well-heeled ladies riding in rickety two-wheeled carts.

A lot of old-timers of Vernor’s generation went on record lamenting the loss of the slow, charmed tranquility of pre-industrial Detroit, with its sleepy streets, big trees and quirky French habits. Not Vernor. Sure, he was a little old-fashioned. When his brother moved a little far from the city center, Vernor warned him of Indian raids. He wore his Civil War–era side-whiskers for his entire life. But for the most part, Vernor was ready for the future. The reason he ended up in politics in the first place was because he wanted a better sewer on the street near his business—the damn thing was always flooding his basement. He wanted to get rid of the dusty old farmers’ market in Cadillac Square—a provincial throwback and haven for ne’er-do-wells—and implement modern reforms.

So when the streetcar issue came up in the council—when Mayor Pingree called for electric lines, a three-cent fare and an end to private monopoly—Vernor understood. He knew the importance of modernizing Detroit and keeping pace with the thrumming national metropolis Detroit was about to become. Vernor wanted streetcar improvements. He just didn’t think that the city would do a very good job of improving them.

Meanwhile, streetcar employees were organizing and agitating. Drivers were asking for a ten-hour workday (to replace the standard twelve-hour split-shift), but employees who threatened to unionize were in turn threatened with wage cuts or summary dismissal. On April 21, 1891, streetcar workers went on strike. Curious spectators became angered sympathizers at the sight of a strikebreaker with a gun who was threatening to shoot anyone blocking the line.

A mêlée ensued. “Silk-gloved and plug-hatted men, side by side of horny-handed, mud-bespattered, unkempt men, vied with each other in tearing up the tracks,” wrote one observer.

In one of those potent Detroit-making stories we tell over and over again—like the baker with the pony knocking his pipe on his boot and burning down the city—U.S. Postmaster General Don M. Dickinson led a mob down Woodward Avenue in hauling a streetcar and heaving it into the river.

Despite pleas from prominent citizens, Pingree refused to call in state troops. In a speech at the scene of the unrest, Pingree encouraged workers to negotiate with their employers. To the employers, he suggested terms of arbitration—shorter hours, higher pay—that were reluctantly accepted.

Back at city hall, the streetcar company promised that plans were about to get underway for a sweeping electrification project—if only the city would grant it another thirty-year franchise. No property taxes; no increase in revenue sharing. Just the pinky-swear that there would for sure be an upgrade. The Common Council approved the request. Mayor Pingree promptly vetoed it.

Coupled with the strike—which curried abundant public favor for the streetcar unions and for Pingree—it was the starting shot (no actual bullets fired, thankfully) in what pundits would come to call the Thirty Years’ War for control of the streetcar system.

In 1893, while the extension of the private streetcar deal was tied up in the courts, Vernor led a special committee of the Common Council to negotiate a franchise for the Detroit Citizens Street Railway (contrary to what the name suggests, it was owned by some deep-pocketed investors from New York). It passed, but Pingree vetoed this, too—the fare system was too high. He had promised the citizenry a three-cent streetcar. And Pingree, as he continued to show, kept his promises.

Pingree had been dead for twenty years when the Thirty Years’ War finally came to an end. In 1921, under Mayor James Couzens, the city finally took control of the streetcar system.

Vernor—who would serve on the Common Council for twenty-five years—reversed his stance on public ownership. As he avowed that he had been wrong about private ownership all those years ago, he voted to approve a municipal takeover.

But for the rest of the time they worked in Old City Hall together, a chill settled between Alderman Vernor and Mayor Pingree. Though they had been friends, business peers and brothers in war, the wedge of progress—and how to achieve it—separated them in politics, and Vernor never walked warmly into Pingree’s office again.

Today, Vernor is mostly remembered for his soda, although in obituaries at the time of his death, his famous ginger ale is a footnote to his expansive career in city government during a time of flux.

Pingree is remembered as a fighter, a reformer and a take-no-prisoners progressive. And he is remembered by his monument in Grand Circus Park—just across Woodward Avenue from a memorial to another Pingree rival.

ETERNAL RIVALS

In 1897, after three terms as mayor, Hazen Pingree packed for Lansing to serve as governor of Michigan. (He had tried to persuade the courts that he could hold both offices at the same time, that feisty so-and-so.)

Pingree wanted to leave his office in Detroit to a handpicked Republican successor, Captain Albert Stewart, a Great Lakes sailor who acted and spoke like one. He promised to do in office “whatever the governor tells me to do.”

Captain Stewart lost the election to William Cotter Maybury, a Democrat “famed if not for inventing, at least perfecting the art of going through the neighborhoods kissing babies,” wrote Malcolm Bingay. Maybury was a mustachioed gentleman bachelor-lawyer who had served two terms as a U.S. representative.

In Lansing, Pingree struggled to pass meaningful reform measures, blocked at every turn by a cabal of unmoveable senators that came to be known as “the Immortal Nineteen.” His street-level, sweat-and-shirtsleeves tactics—like the potato patch plan, which turned vacant lots into pocket gardens to help the urban poor stave off starvation, or the time he marched into a school board meeting and arrested four of the board members on corruption charges—made him a walking monument to progress in Detroit. But Old Ping couldn’t gain any traction at the capitol.

Back in Detroit, Maybury made excellent speeches and planned a magnificent bicentennial celebration, with parades, floats, pageants and feather plumes. He was genial and pro-business and tried not to rock the boat. Detroiters thought he was a pretty nice guy.

Pingree decided to retire at the end of his second term. On December 31, 1899, he cleared out all of the seats from the House floor and threw a huge New Year’s Eve/Turn of the Century party. Future president Teddy Roosevelt came dressed in his Rough Riders uniform. Revelers stayed up until dawn, making speeches and toasting their outgoing governor—who, it’s only natural, was planning a grand retirement big-game hunt in Africa. You know…to unwind.

He never made it home from the safari. He fell ill with dysentery on the hunt, was rushed to London and died there, despite the emergency care of King Edward VII’s own physicians. He was sixty.

As soon as news crossed the wire in Detroit, the city slipped into grief. Mourning bunting draped city hall with banners reading, “Ambitious. Fearless. Staunch. True.” And then a funny thing happened: people started calling the newspaper offering five-, ten- and twenty-five-cent contributions for a monument to Pingree’s memory.

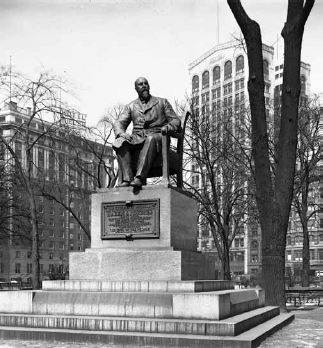

Four years later, a statue of Pingree, perched at the edge of a chair, his foot overhanging the pedestal, like he’s ready to leap into action, was unveiled at Grand Circus Park. More than five thousand people donated to build the statue.

Hazen S. Pingree Monument in Grand Circus Park, circa 1905. Sculpture by Rudolph Schwarz, unveiled in 1904. Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

William Cotter Maybury Monument. Sculpture by Adolph Alexander Weinman, unveiled 1912. Photo by the author.

When William Cotter Maybury died in 1909, his friend and former police commissioner George W. Fowles proposed a public monument to the late mayor across Grand Circus Park from the lurching Pingree memorial. The public was unenthused, so Fowles and some of his friends from the Maybury administration and the business community quietly, privately raised $20,000 to build one anyway. It was unveiled in 1912.

Adversaries in life, they are entrenched in a never-ending showdown in Detroit’s oldest park. But while Pingree looks stalwartly up Woodward Avenue, William C. Maybury holds a different gaze: across the wide boulevard, toward Pingree, as if wondering, “What made him so special?”