THE ARCHBISHOP

I never used to second-guess memorial statues. You know the type: tall, bronze and handsome and sometimes on a horse. If you watch for them when you’re traveling, you start to see the same faces: Thaddeus Kosciuszko, Robert Burns, Dante, Leif Ericson, Joan of Arc and pretty much every Civil War general ever.

Then I met Jim Scott. And now I always wonder.

Who was this man of mystery—Detroit’s “boss romancer,” raconteur and prankster millionaire? And why does he have a larger-than-life statue—and to match, a gleaming marble fountain, like something from a Cecil B. DeMille set—in his honor?

Let’s start from the top. James Scott was born on December 20, 1831, in a house on Woodward Avenue. Though his early life was not without hardship—his mother died before he turned three and his father when Jim was a teenager—Scott was born wealthy, and he never had to work too hard. His father, John Scott, had come to Detroit penniless and spent years on construction contracts, investing in land and building wealth; he retired into public service. By that example, Jim Scott’s chosen path in life was doubly irritating to the virtuous entrepreneurs of this make-it-yourself town.

When he was twenty-five, he started a gambling hall for faro players—and, with it, a reputation that followed him to his death and beyond. Was he a gambler? No one is sure, but it’s likely. Of course, in the 1850s, Detroit was “wide open,” as Robert B. Ross defended in 1905:

Drinking was the rule…In the best houses, decanters of wine, brandy and whiskey always stood on the sideboards. Gambling was not only tolerated, but cultivated…Almost every business man held the opinion that gambling increased the prosperity of a city…The average gambler was well-dressed, polite, generous and a good story-teller…and scrupulously honest.

Well, maybe. Faro was wildly popular in American frontier towns. It was also notorious. “In an honest game of Faro splits should occur about three times in two deals,” according to The Fireside Book of Cards. “But an honest game has always been a great rarity; faro was a cheating business almost from the time of its invention.”

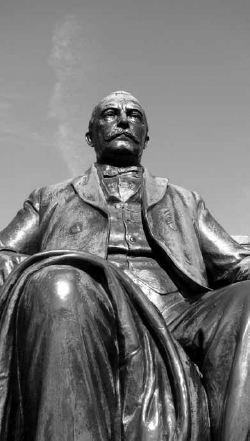

The life-size monument to Jim Scott erected with his grand Italianate fountain. The artist hoped that no one would recognize him without a top hat. Sculpture by Herbert Adams, 1925. Photo by the author.

Yes, the mayor asked Scott to shut down his gambling hall for a while. But it was only because some of his clientele were making unwelcome comments to ladies on the street—wasn’t it?

Scott seemed to edit his own biography as he lived it. Was he really a millionaire? Some said he was; to them, Scott said, “Prove it,” and no one could. Why did he leave for St. Louis? What did he do when he was there? Rumors spread that he lost a huge chunk of his personal fortune in a rigged game of faro and forswore gambling forever. Others noticed a few new diamond rings on his fingers when he returned to Detroit and raised their eyebrows. Scott liked to brag about his high-rolling years on the Mississippi, winning jackpots and outrunning the police, but his associates, including former Detroit mayor John C. Lodge, privately confessed that Scott was too cheap to gamble even a nickel on the likelihood that the sun would rise.

Scott favored white bow ties, ruffled shirts and, long after they were out of style, tall beaver top hats. Because of his long black beard, he was sometimes called “the Archbishop,” but his flamboyant sense of fashion is not what made his reputation. At the city’s tony hotel bars and social clubs, Scott held court, drinking and telling long-winded, ribald and apparently insufferable jokes.

The Detroit Tribune ran a profile of Scott, “Detroit’s boss romancer,” in its March 14, 1885 edition:

He never tells the same story twice, and does not depend on traveling men for his stock of stories, but invents them himself. He tells lots of funny things in different dialects…There is one friend of Jim’s, however, who insists that he dishes up old chestnuts, and when this friend sees the joker coming, he runs and hides in the hay-mow.

How bad were his jokes? Here’s one of them, paraphrased from the same article: Two friends take a recently dead guy to the bar with them. Then they leave the dead guy at the bar when it’s time to pay their tab. The bartender gets mad that the dead guy won’t pay, and he punches the dead guy in the head. The corpse falls to the floor. And then the two scofflaws run back inside the bar and say, “Oh, my God! You killed him!” And the bartender says, “So what if I did? He pulled a knife on me first.”

Beyond the barroom, too, Scott had a distinctive sense of humor—or a delirious sense of spite, depending on whose books you read. In 1891, construction began on Jim Scott’s masterstroke of mean wit: the Folly.

When the neighbor next to Scott’s lot at Park and Peterboro refused to sell—quoting him an exorbitant price—Scott had a mansion built that rivaled all the rest on the block. But only from the front. In the back of the house—the side facing the neighbor—the mansion was nothing but a brick wall, three stories high, blotting out the sunlight and replacing a view of the boulevard with an ugly façade.

Scott never lived in the house. He didn’t rent it. He wouldn’t sell it. He just left it. But he took pride in personally mowing the lawn. Wrote Ross: “This is the only manual labor he ever did in his life.”

But was he a venomous cad? Or just a merry prankster? Some evidence suggests that Scott had cast himself in the role of a “witty sport,” and his hijinks occasionally garnered a corner or two of a national newspaper—perhaps Scott was experimenting with what we’d call “personal branding” today. It was rumored that he was actually quite generous when no one was looking; waiters loved him for his lavish tips, and he had a yearly competition with innkeeper Seymour Finney to see who could file his city taxes in the timeliest manner.

One reporter caught Scott delivering fruit and blankets to a family who’d lost their home in a fire. The lead: “Even the heart of the meanest man in town had been touched.” When the story ran the next day, Scott called the editor in a rage, demanding that the paper issue a retraction for the “attack on his character.” Was he worried that a story of his soft, thoughtful center would sully his “surly jester” image?

Reprehensible lout or harmless rich eccentric, we wouldn’t be asking these questions if Scott had died quietly—by now he would be lost to history. But Scott saw to it that Detroiters like us would be debating the old wise guy’s finer points of personality more than a century later.

It’s either the most outrageous act of self-aggrandizement in city history or the greatest last laugh in public art. When Clarence M. Burton—with his lawyer hat on—executed Scott’s will in 1910, he shared the shocking news with the world: Scott had left most of his $600,000 estate to the city for a grand fountain on Belle Isle. The catch? The city also had to build a statue of Jim Scott.

The controversy was immediate. Scott was not a well-liked man; he had no friends, and no one had any good reason to stick up for him. The shady dean of the faro house, litigious prankster, teller of off-color jokes and cane-shaker at neighborhood kids? A man whose highest aim in life seemed to be aggravating as many people as possible? How could the city in good conscience celebrate the memory of such a rake?

The churchy contingent marched out first against the fountain, naturally. The man drank, for heaven’s sake. From the temperance movement’s perspective, which once again dominated Detroit’s moral conversation (in less than ten years, prohibition would be the law of the land), the life of Jim Scott looked pretty depraved, almost like a missed opportunity—a soul that had not been saved. “Only a good man who has wrought things for humanity should be honored in this way,” said Bishop Charles D. Williams.

People who spent their whole lives building fortunes from scratch resented Scott and his fountain, too. J.L. Hudson, immigrant and department store magnate, put it a little more plainly: the fountain would be “a monument to nastiness and filthy stories. Mr. Scott never did anything for Detroit in his lifetime, and he never had a thought that was good for the city.”

Except, of course, for the fountain. Leaving your colossal estate to the city for a public works project—that counts for something, right?

And that’s exactly the tack taken by his few, but famous, defenders. Like former senator Thomas W. Palmer, a city sage at eighty years old, who stood before the Common Council and shared a memory of Scott, just a vulnerable boy in a schoolyard. Hands shaking, he spun a dreamy parable about a man who grew up without a mother or a YMCA, and though he’d squandered his life on malicious pursuits, he faced mortality and found that boyish hope still alive in the pit of his person, thereafter resolving to right his life and leave something that the young men and women of Detroit could enjoy forever.

Grandiose, certainly. Even remotely true—who could ever say? But the old senator, maybe just because he was so old, touched hearts that day.

Others, like Alderman David Heineman, rightly pointed out that most members of the Common Council had no business throwing stones at Scott’s character: “I can look around this office and see pictures of men who played poker with Jim Scott. I say the bequest should be accepted.”

The Common Council referred the matter to committee, which reported in December 1910 that after public meetings and discussions with Scott’s acquaintances, it was determined that

those objecting have been misled as to the occupation and character of the deceased…Not a single voice accused or even intimated in the slightest degree that he was dishonest or ever attempted to wilfully or knowingly wrong any one; no one questions his integrity, and his occupation was that sought by ninety-five percent of the American people, a “retired capitalist”…The only thing which is pointed to as being against him are the follies of youth, and those he discarded over 40 years ago.

Opined the New York Times on January 29, 1911, when it shared the news that the impasse had been resolved:

This is the story of a man who led a practically blameless life for eighty years, according to the preponderance of testimony, as blameless as that of the average man at least, who loved his home, his family, his friends, and his city, the latter so much that when he died he left five-sixths of a fortune of $600,000 to the municipality of Detroit with which to build a fountain on Belle Isle, and who has been since his death, a year ago, unmercifully reviled for his generosity. James Scott was his name—“Jim” he was universally called.

The fountain, and its matching monument to an otherwise unimportant man, was a go. In the years between Scott’s death and the start of construction, the estate he left the city rocketed in value to more than $1 million, and the scope of the project grew with it. When it was finished, the project had changed the very landscape of Belle Isle’s west end; the fountain concourse was elevated so water could cascade into a 500-foot-long reflecting pool. Cass Gilbert, architect of the U.S. Supreme Court building, designed a Neoclassical marvel with a central water jet capable of 125-foot sprays, liberally adorned with spitting Neptunes, stately lions, turtles, dolphins, maidens and a fountain bowl lined with handmade-in-Detroit Pewabic pottery tiles.

The statue of Jim Scott is, indeed, larger than life—not two and a half feet tall, as one fountain detractor suggested, nor made of soap. He is not wearing a hat, which some hoped would make the relentlessly top-hatted Scott unrecognizable. He does not have the majestic view of the city he had hoped for: he is shadowed by the fountain’s grandeur, and few visitors today know or care who he is.

But the Archbishop’s fountain is, indisputably, a gem. Children play in it. Photographers take pictures of it. Couples get married in front of it, and at night it lights up like a firework.

And for that, you can almost see Jim Scott smirking. The joke, once and for all, is on us.