LIQUOR

Here’s a popular notion that is probably true: when Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac set off from Montreal for Detroit in 1701, he packed with his cargo fifteen barrels of brandy. Shortly after he arrived, he ordered more—three hundred livres worth.

Some American towns were founded by religious pilgrims, some by cranky homesteaders and others by new industries or favorable locations. Detroit was founded by traders, and where you had trade, you had booze.

Cadillac also arrived with two Jesuit priests, which obviously caused problems right away. Was it not wrong, the Jesuits begged, to introduce the evils of alcohol to the local Indian community? Would it not promote violence, crime and degradation?

In response to such concerns—borne out by what usually happened when Europeans brought boatloads of brandy to town—the French crown attempted to regulate the commerce of intoxicants. But it couldn’t outlaw it completely, traders argued, without killing trade, as long as independent traders and the British had no problem trading alcohol for pelts.

So Cadillac—in addition to his roles as commandant, trader-in-chief, director of the bureau of land management and self-styled marquis du Detroit (he asked King Louis for the title repeatedly)—became the city’s first liquor commissioner. From a central storehouse, he distributed his eau de vie as rations for his soldiers—after all, no fish dinner was complete without a little brandy—and as currency for Indian fur traders. And beer brewing was one of the many trades that Cadillac ruled could not be practiced without his say-so (along with blacksmithing, locksmithing and armor making). A couple of hogsheads of ale might even be part of your license fee.

For more than a century—under French rule, under British rule and as part of the United States—things went on like this in Detroit. People decried the trade of liquor, then participated in it despite its effects and then decried it some more.

After a visit to Mackinac in 1799, a despairing Father Gabriel Richard wrote:

The traders themselves confess that it would be better for their own profit not to give rum to the Indians, but as the Indians are very much fond of it, every trader says that he must give them rum not to lose all his trade…God knows how many evils will flow from that trade. Some have observed that English rum has destroyed more Indians than ever did the Spanish sword.

Many historians have attributed Richard’s public falling-out with the prominent trader Joseph Campau to Campau’s liquor trade. Although they no doubt aggravated each other on the issue, Richard himself bought booze from Campau: large quantities of imported wine.

In 1798, Michigan held its first election in a bar. The race: the first representatives of the Michigan Territory to the U.S. Congress. The contenders: John May, a former British subject, and Solomon Sibley, an itinerant pioneer lawyer who came to Detroit by way of Ohio by way of New England. The setting:John Dodemead’s home, tavern and sometimes county courthouse. After three days of voting, Sibley won the seat. John May accused him of plying voters with liquor to encourage their votes.

Dodemead was also the county coroner. After the official incorporation of Detroit in 1802, Dodemead was granted the city’s first tavern license.

Sibley was active in city politics for the rest of his life. In 1815, he was chairman of the board that sought to create order in Detroit—standards and regulations that made it a real, functional city. Provisions included speed limits, a ban on horse racing, a fire code (violations: storing hay too close to a house, neglecting to keep your chimney clean and failure to keep two water buckets in your home), a one-dog limit per household and a twenty-dollar liquor license fee for taverns and places of public entertainment. Selling liquor on Sundays was against the law. “Drunken orgies in taverns” were punishable by fines from three to ten dollars.

In 1818, Benjamin Woodworth opened his new-and-improved hotel, renamed the Steamboat Hotel, just in time for the heralded arrival of the Walk-in-the-Water, the first steamboat to sail to Detroit from Buffalo, New York. Over the years, Woodworth’s hotel had hosted many of Detroit’s most important galas, including a Grand Pacification Ball celebrating peace between Britain and the United States after the Treaty of Ghent officially ended the War of 1812, as well as a reception for President James Monroe—the first president to visit Detroit—in 1817.

Woodworth shocked Detroit in 1830 when he offered to act as sheriff and hangman for Stephen Simmons, who was sentenced to death for killing his wife. Analysts blamed a drunken rage. It was the last state execution in Michigan’s history.

By the mid-1830s, Detroit had one saloon for every 13 residents (total population: about 2,200). At a bar, you could get a free lunch, read any number of newspapers, smoke a cigar, play cards, discuss current affairs, conference with business associates, campaign and legislate. Visitor A.A. Parker wrote in 1835:

The streets near the water are dirty, generally having mean buildings, rather too many grog shops among them, and a good deal too much noise and dissipation. The taverns are not generally under the best regulations, although they were crowded to overflowing. I stopped at the Steamboat Hotel, and I thought enough grog was sold at that bar to satisfy any reasonable demand for the whole village.

As Detroit’s population exploded, so did its traffic in intoxicants. German immigrants in the 1840s—like Bernhard Stroh, whose family of innkeepers had brewed beer in Bohemia since the late 1770s—brought their refined lager style and genteel beer gardens to Detroit and planted an industry that would innovate, influence and prosper for the rest of the century.

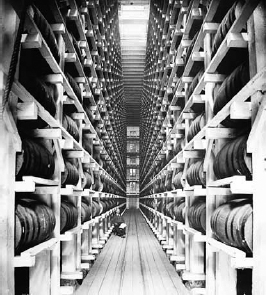

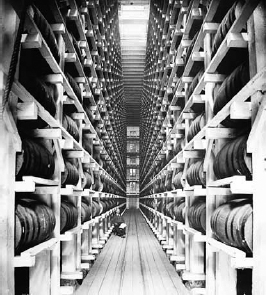

Rack warehouse, Hiram Walker & Sons, Walkerville, Ontario. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection, LC-D4-42672.

Meanwhile, it was cheaper to make whiskey from grain than to ship it, so distilleries boomed. The city was so profligate with spirits that Detroit grocer and distiller Hiram Walker moved operations across the river, where real estate was cheaper, liquor laws were looser and competition was slight. From his Canadian distillery—in Walkerville, the town he founded, financed and settled himself—Walker produced the whiskey that became Canadian Club. Its international allure made it a top seller in America, annoying American distillers.

Bars for every taste, class and purpose sprang to life: bars for tourists and travelers, watering holes for local thirsts, bars with attached family restaurants where ladies were welcome (they weren’t at most bars) and exclusive clubs for society types. At the Young American Saloon, opened in 1856, you could order meals “furnished at any hour, at a moment’s notice.”

The Bank Exchange bar published this little poem about its oysters:

Of all the oysters ever I see,

At the Bank Exchange you will find the best.

They come fresh right from the sea,

And so are sold for less.

The Bank Exchange also printed a guarantee that its seafood was better than its verse.

At Tom Dick’s Barrel Bar, you had your choice of two brands of whiskey, served straight from a tapped wooden cask. The premium brand was best served neat. The other brand, “Twa Bits,” was only remotely palatable when served with a couple lumps of sugar in the bottom of the glass—hence its name.

Seymour Finney, a tailor by trade, opened a tavern in 1850 and later a hotel in present-day Capitol Park. Next to the tavern he built a barn, where he sheltered escaped slaves traveling to freedom on the Underground Railroad. His customers at the bar, some of whom might have been slaveholders once, had no idea what was happening right behind them.

One of the oldest bars in town, known as the Old Shades (to distinguish it from the less old, but still really old, bar next door, the Shades), was creaky and moss-grown as early as the 1840s. When it was torn down in the 1880s, the Detroit Free Press declared the bar’s history to be “lost to the gloom of antiquity.” Its reporters were unable to find anyone alive—even the oldest of the old-timers—who could remember a time when the Shades was not an ancient place.

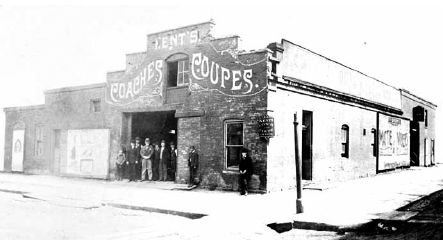

Seymour Finney kept a barn behind his inn and sheltered escaped slaves making their way to Canada along the Underground Railroad. Ohio Historical Society.

In the winter, when the river froze over, enterprising barkeeps would set up shanty saloons between Detroit and Canada. Traders hauling goods across the ice would stop for a drink or six, so trade traffic tended to take a steep dive during the cold months.

One bar on the rural outskirts of town offered a holiday attraction: shooting your own poultry. Wrote General Friend Palmer:

This tavern used to be well patronized by the farmers living near the city and by the general public. It was a grand place for shooting turkeys, geese and chickens Thanksgiving and Christmas. The fowls were securely fastened to a box or something some distance in the rear of the tavern…The crowd would load and fire from the back shed of the tavern, and when the day’s fun was over, they would spend the night in the bar room raffling off the victims of the day.

TEMPERANCE AND INTEMPERANCE

In 1853, the Reverends J.A. Baughman and George Taylor unfurled a 1,300-foot-long bolt of cotton before the Michigan legislature. Pasted on the cloth were petitions in favor of a law prohibiting the sale of liquor except for medicinal, scientific and sacramental purposes.

It was not the state’s first attempt at prohibition, and it would not be the last. Concerns about the effect of alcohol on the Indian community gradually gave way to debates about what kind of moral character the city should keep and how it should deal with public brawls, private domestic unrest and the encroaching poverty of heavy-drinking immigrants.

Secret temperance societies began to organize in Detroit as early as 1830. In 1836, the first meeting of the Detroit Young Mens’ Temperance Society resolved to distribute a Temperance Almanac to every family in the city. Ten years later, voters in Detroit passed a law prohibiting the grant of liquor licenses. The Common Council tried to appeal it, but the city attorney ruled the law valid and binding.

“The city resolved not to grant licenses. The dealers then resolved to sell,” Silas Farmer wrote. Saloonkeepers ignored the law and authorities refused to enforce it, so the city brought back the license system in 1847.

In 1850, Michigan drafted a new constitution, and temperance advocates succeeded in including an article prohibiting the sale of liquor statewide. It was the starter shot in a twenty-five-year tug-of-war between the temperance movement, city government, law enforcement and saloonkeepers.

The city continued to ignore the letter of the law, issuing liquor licenses as though nothing had changed. The only other option was to not issue liquor licenses, which brought in cash for the city—and the city knew that the saloons would continue to exist no matter what.

Temperance activists tried everything to get the law to stick. They organized a sort of vigilante enforcement posse, the Carson League, which disbanded in 1853 after Detroit’s grocers, hoteliers and barkeeps met at city hall to pass a resolution deeming the Carson League a menace: “We have public officers whose duty it is to administer our laws, therefore we deem any number of persons associated for that purpose to be an illegal society, or league unknown in law, and dangerous to the peace and harmony of the community.”

New prohibition laws were passed: the “Ironclad” law of 1855, which declared all payments for alcohol illegal and recoverable by the state; an ordinance in 1858 that required the closure of saloons at 11:00 p.m.; an 1859 law that required each county to hire a chemist as inspector of liquors; and an 1861 law that required bars to close on Sundays.

Nothing changed. Compromises were made and demands scaled back. Winemaking and beer-brewing were legalized. Bar owners continued to do as they pleased. Occasionally, a new temperance law would spook people, and bars would close in droves only to reopen months later. Saloonkeepers and liquor manufacturers were arrested, only to have their cases thrown out by judges who had better things to do. In 1854, when the state’s prohibition law was briefly ruled unconstitutional, Detroiters celebrated with a one-hundred-gun salute and, it’s safe to assume, a fabulous quantity of booze.

Temperance efforts finally won a little in 1865, when the city finally established its first cohesive (and paid) police force. A notice was posted in the paper after the first Sunday under its authority:

A Quiet Sunday: For the first time in years the great city of Detroit yesterday observed, outwardly at least, the first day of the week with becoming solemnity. All the saloons, bars, and beer-gardens were closed.

Even that effort didn’t last. Barkeeps continued to lobby the city to lift the regulations. Temperance societies continued to petition for new laws. This continued, tediously, until 1875, when the article of prohibition in Michigan’s constitution was repealed.

All told, the number of breweries doubled, saloons tripled and distilleries quintupled during the first prohibition era.

A DRINK IN DETROIT

We forget about Michigan’s first prohibition for a couple of reasons. It wasn’t a national experience, first of all; secondly, it was largely ignored. The images of prohibition under the Eighteenth Amendment—rumrunners driving cars across the ice, mob violence and speakeasies—remain salient, and so many Detroiters are personally connected to it. Ask the next person you meet at the bar in Detroit about the Purple Gang—odds are good that her grandfather was mixed up with them or else they gave that grandfather hell. While I was tinkering with my manuscript over a pint of Michigan craft-brewed pale ale, my waitress told me that the Purple Gang drove her Irish Catholic grandfather out of town. I told her that my Russian Jewish grandfather got busted running sugar for his friends in the Purple Gang.

So it’s funny that, at the turn of the twentieth century, with a new Detroit on the horizon and a drastic new mood of temperance rolling in like a thunderstorm, business happened in Detroit bars that changed world history.

Malcolm Bingay, an editor of the Detroit Free Press, wrote in his memoir, Detroit Is My Own Hometown: “Back then, when sports reporters were looking for stories from the leaders of the ‘auto game,’ they did not ask where these men were; they merely asked, ‘Which bar?’”

John and Horace Dodge, founders of the Dodge Brothers engine and chassis company, were hard-drinking brawlers who favored the dingy workingman’s saloon over the tony gentlemen’s clubs and hotel bars preferred by the city’s executives.

After John’s death in 1920, Schneider’s—the brothers’ favorite watering hole—kept a bronze bust of him behind the bar next to a bottle of Noilly Prat vermouth. Sometimes, on especially misty nights, the bartender would pour Dodge’s signature martini and waft it under the bust’s nose.