TRAFFIC

In the name of humanity I would inquire whether there is any law or ordinance in this, your city, to prohibit furious driving, and, if there be, whether there is anyone to enforce it?…

Those who want to try the speed of their unfortunate nags, and want to exercise their lungs by unearthly yellings, can go elsewhere.

–letter to the editor, Detroit Free Press, December 24, 1859

This is the Motor City, and we are proud of our roads, pockmarked and potholed though they may be. (It’s just that we’ve worn them out with love…right?) We boast the first stretch of concrete-paved road in the country, and our robust system of expressways led to other landmarks, like some of the country’s first suburban shopping malls. But our adored streets—a yarn ball of interstates, highways, mile roads and wide, divided boulevards—were hundreds of years in the making.

Silas Farmer painted a colorful picture of street life in the mid-eighteenth century:

The streets, in the olden days, afforded many a strange and picturesque sight. Troops of squaws, bending beneath their loads of baskets and skins, moved along the way; rough coureurs de bois, with bales of beaver, mink, and fox, were passing to and from the trading stores, and, leaning upon half-open doors, laughing desmoiselles alternately chaffed and cheered their favorites; here a group of Indians were drying scalps on hoops of a fire; others, with scalps hanging at their elbows, dancing the war dance…staid old judges with powdered cues exchanged salutes with the officers of the garrison, who were brilliant with scarlet uniforms, gold lace, and sword-knots; elegant ladies with crimson silk petticoats, immense beehive bonnets, high-heeled slippers, and black silk stockings, tripped along the way; and ever and anon the shouts of soldiers in the guardhouse, made wild with “shrub” and Old Jamaica Rum, were heard on the morning air, and at times troops of Indian ponies went scurrying through the town.

Before 1805, the mightiest road in town spanned about twenty feet across; most were less than fifteen feet wide. A promenade, the chemin du ronde, ran along the riverfront, but when it was rainy (and it was rainy a lot), the road flooded, and it was back to old-fashioned ways of getting around: on foot, by pony or in a canoe.

Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac came to Detroit with three horses, but two of them died upon arrival, leaving the entire post with one steed, named Colon. If you needed a horse for some farmstead chore—or to be dragged in your sled to the top of a snowy hill—you could rent Colon for the day.

Later, French settlers brought ponies to Detroit, and for a while they were the be-all, end-all of getting around. Farmers branded their ponies and then released them to graze. If you needed one, you could just hike out to the commons and pick one out, according to Palmer, presuming it did not already belong to someone:

The French residents were proverbial for the love they bore their horses; and the traditional French pony, wiry, strong and fleet of foot, gave them all they desired in that direction. Every French family owned two or three ponies, at least, some of them more…Joseph Campau owned a vast number. Go where you would through the woods adjacent to Detroit, nearly all of every drove of horses you came across had the letters “J. C.” branded on the flank. So numerous were these ponies that they would venture into the city in droves during the warm summer nights, attracted by the salt that the merchants had stored in barrels in front of their places of business.

These ubiquitous and sturdy creatures were used to pull two-wheeled horse carts, which were a great equalizer; everyone used them, from the working poor to the most fashionable society ladies, who would lay down a buffalo skin and climb in the back. Judge Solomon Sibley was one of the few residents of that old town who had a proper four-wheeled carriage. Just like your one friend with a pickup truck, people were always asking to borrow it—people like the venerable governor of the Michigan Territory, Lewis Cass:

[Cass] frequently solicited the loan of it, saying to his old French servant, “Pierre! Go up to Judge Sibley, and tell him if he is not using his wagon today I should like to borrow it;” and as Pierre started off he would sometimes call after him and say, “Come back, Pierre! Tell Judge Sibley that I am going to get a wagon made, and after that I will neither borrow nor lend.”

So much mixed and unregulated traffic on Detroit’s narrow byways—pony carts, horse riders and pedestrians, as well as the old pastimes of horse and carriage racing, which endured from at least the 1750s until the invention of the combustion engine—caused hazardous scenes.

“The streets of that part of Detroit within the stockade are so narrow that foot passengers have difficulty at times to keep clear of horsemen and carriages unless they go slow,” noted an 1802 ordinance that forbade fast driving. That ordinance was strictly enforced. Members of the board of trustees that drafted it were among those disciplined for fast horsemanship in some early evidence of Detroit’s dragster habits.

The city also had to find a way to keep wandering dogs, cows, fowls and other animals out of the street, leading to the establishment of a city pound-keeper to maintain zoological order. Farmer speculated that pound-keeping might even be Detroit’s most “ancient and honorable” profession.

In 1805, the Great Fire leveled the village, and Detroit needed a plan. It was weird luck that the city had just been incorporated under a new administration and established as the capital of the territory; a new governor, Isaac Hull, and two territorial judges, John Griffin and Augustus Woodward, were already on their way. (A third territorial judge, Frederick Bates, was already here.)

Augustus Breevort Woodward is one of Detroit’s all-time best eccentrics. A perpetual bachelor and a friend and flatterer of Thomas Jefferson, he favored rumpled suits, showering in the rain, philandering and, even more than most in those days, liquor. Born Elias Woodward, he changed his name to better reflect the imperial and scholarly heritage he felt he had inherited. He studied law, took a shine to speculative science, wrote pamphlets on the substance of the sun and emerging American political theory and disagreed with most people.

Shortly after surveying the fire’s damage, Woodward returned to D.C. with Hull and acquired a land grant from the federal government for ten thousand extra acres in Detroit, enough to give every resident a donation lot of up to five thousand feet. Then he went to work on his masterpiece: Detroit’s majestic city plan.

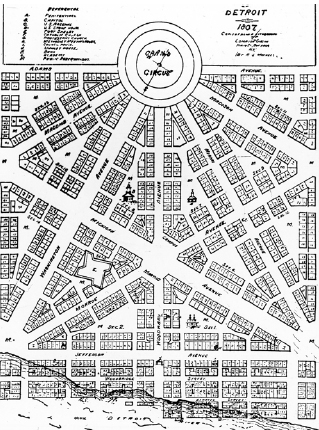

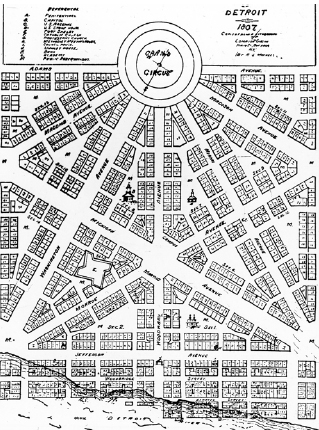

A portion of the Woodward Plan for Detroit after the fire. Detroit City Plan, 1807. Art, Architecture & Engineering Library Lantern Slide Collection, University of Michigan.

Riffing on Charles L’Enfant’s plan for Washington, D.C. (though some grander minds have imagined Woodward drawing the plat based on his observations of the stars and planets), Woodward sketched out a new city, with one fat road running up into the country at a right angle with the riverfront. This would become Woodward Avenue (because the road, Woodward remarked sarcastically, ran toward the woods). He contributed some classical character—the Campus Martius, for instance, named after the public square of ancient Rome. He honored presidents instead of saints, like his friend Jefferson, for whom he named the road that ran along the river. And he envisioned grandeur: abundant full- and half-moon parks, public squares and gridded streets interrupted by broad, angled, tree-lined avenues.

Like Woodward himself, it was not popular. Wrote one visitor:

I have seen a plat of this city. I wish, for the sake of the designer, towards whom personally I entertain the kindest feelings, that it had never been conceived by him. It looks pretty on paper, but is fanciful and resembles one of those octagonal spider webs which you have seen in a dewy morning, with a center you know, and lines leading out to the points round the circumference and fastened to spires of grass. The citizens of Detroit would do well, in my opinion, and their posterity would thank them for it, were they to reduce the network of that plan to something more practical and regular.

It is easy to forget that the Woodward Plan was abandoned in 1811 before it was halfway complete; the modern-day streets of Detroit are baroque as it is, with huge diagonal thoroughfares slicing through the grid streets, cramming at times into awkward triangular intersections and half circles. It is enough to confuse even a regular visitor, but it could have been worse. Wrote Clarence M. Burton:

Imagine the present city, with a river frontage of eleven miles, constructed on this plan. A Grand Circus Park every 4,000 feet of that distance and twice as many semi-circular parks and hundreds of triangular parks like Capitol Square and the Public Library. There would be as many squares like the Campus Martius as there were Grand Circus Parks. Even the natives would get bewildered in the labyrinth.

Visionary, pretentious or both, the Woodward Plan gave Detroit room to grow. And grow it did, but not right away. Streets still weren’t paved. Grand Circus Park, the most recognizable and beautiful vestige of the Woodward Plan, was a swamp and a dumping ground as late as the 1840s.

IMPROVEMENTS

Unlike the fire before it—which some historians consider an almost baptismal event, cleansing away the grime and stagnation of the old French era and laying a clean slate for cosmopolitan improvements—the War of 1812 is not generally thought of as a blessing in disguise, and especially not for poor Detroit, so embarrassingly surrendered and only sheepishly returned.

But the war did a few small favors for the city. First of all, it created the first overland routes from Detroit into the territory, across the Ohio Valley and toward the territorial boundaries. The roads were rough—just craggy footpaths or, at best, “corduroy” roads made from felled logs—and they barely improved the wilderness and swamps through which they ran. But they were better than what existed before, namely nothing.

The second grace of the war was that it introduced some new people to the Michigan Territory. Officers, soldiers and volunteers from Kentucky, Virginia, Ohio and Pennsylvania were charmed by the region’s rugged scenery—the feral fruit orchards, the miles of glinting shoreline and the prairies and oak groves open for anyone to come settle, build a gristmill, start a family farm or take up a trade. Some stayed. Others went home and told their friends that Michigan was kind of a nice place. Word began to spread.

The signal shot fired from the deck of the Walk-in-the-Water on August 27, 1818, was like an announcement to the ages: “Here we go.” The first steamboat to sail Lake Erie—and the first to dock in Detroit—slashed travel time from Buffalo, New York, to a lean and reliable forty-eight hours or so. As a basis of comparison, it took Judge James Witherell nearly a month in 1815—after sixteen days grounded on a sandbar, a brief swim when he fell out of a wagon, several miles hiking in the woods to Cleveland, a charter schooner from Cleveland to Detroit, a four-day delay because of headwinds, a storm that stranded the passengers on a river island eating hard peaches and boiled bark, a boat that sprang a leak, an emergency landing in Malden, Ontario, and a final charter service by canoe or rowboat to Detroit.

Detroit in 1820 and the steamer Walk-in-the-Water, circa 1910. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection, reproduction no. LC-D4-22690.

Even before the Erie Canal, steamboat service on the Great Lakes doubled Detroit’s population. When the canal was completed in 1825, about two thousand people lived in the city. By 1836, that many people were arriving in Detroit every day. Not all of them were destined to stay; many were just passing through, by water or by land, to farther points. So Michigan needed roads. It needed a ton of them. And it needed them fast. They were the single biggest obstacle to growth and progress in the territory.

Governor Cass pushed for provisions to create a network of territorial roads, spoking out from Detroit northwest to Pontiac and Saginaw, northeast to Fort Gratiot, west to Ann Arbor, Ypsilanti and Chicago and south to Sandusky, Ohio. Clear some brush, cut the trees lining the route down to stumps, lay down a few logs and there you had it: a road into the wilderness. Still rough, to say the least. But once more, better than the alternative of no roads at all.

A traveler with Reverend George Taylor in 1837 recounted the following story:

One of these men, a little ahead of the rest of them, discovered, as he thought, a good beaver hat lying in the center of the road, and called his companions to a halt while he ventured to secure it. At the risk of his life, he waded out, more than knee deep to the spot, and seizing the hat, to his surprise he found a live man’s head under it, but on lustily raising a cry for help, the stranger in the mire declined all assistance, saying: “Just leave me alone, I have a good horse under me, and have just found bottom; go on, gentlemen, and mind your own business.” Such a story, of course, could but have a tendency to heighten in a stranger’s estimation, the wonderful attractions of the new State of Michigan.

In the 1840s, with many of the roads built during the first frenzy of internal improvements in the 1820s and ’30s falling into neglect, plank roads were proposed. That allowed private owners to charter and operate roads for a small toll. Although many were never completed and some decayed from lack of use, the plank road situation seemed to alleviate the burden of maintenance on the local government and improve ease of access to places like Ypsilanti, Farmington, Howell, Mt. Clemens and Pontiac for settlers who were, very early on, making homes in what we now call the suburbs.

MAINTENANCE

Within the city, it was a different story. When visitors, encouraged by the newly expedient route to the territory, arrived in Detroit, they found a city ill-equipped to deal with an influx of tourists and traffic. Harriet Noble wrote of her arrival in Detroit in 1824:

For a city it was certainly the most filthy, irregular place I had ever seen; the streets were filled with Indians and low French, and at that time I could not tell the difference between them. We spent two days in making preparations for going out to Ann Arbor, and during that time I never saw a genteely-dressed person in the streets. There were no carriages; the most wealthy families rode in French carts, sitting on the bottom upon some kind of mat; and the streets were so muddy these were the only vehicles convenient for getting about. I said to myself, “If this be a Western city, give me a home in the woods.”

Wrote Captain Frederick Marryatt in 1838:

There is not a paved street in it, or even a foot-path for a pedestrian. In winter, in rainy weather you are up to your knees in mud; in summer, invisible from dust; indeed, until lately, there was not a practicable road for thirty miles round Detroit. The muddy and impassable state of the streets has given rise to a very curious system of making morning or evening calls. A small one-horse cart is backed against the door of a house; the ladies dressed get into it, and seat themselves upon a buffalo-skin at the bottom of it; they are carried to the residence of the party upon whom they wish to call; the cart is backed in again, and they are landed dry and clean. An old inhabitant of Detroit complained to me that people were now getting so proud, that many of them refused to visit in that way any longer.

Marryatt was technically wrong; cobblestone paving projects had begun in Detroit in 1825, but their scope was limited to short stretches of street in front of specific stores or houses. No entire block was paved until 1835.

Fifteen years later, Silas Farmer walked outside and counted “fourteen teams, loaded with wood and other products, stuck fast in the mud on Monroe Avenue, the avenue being only three blocks long.” Children who lived less than two blocks from school still had to ride there on horseback; the streets and sidewalks were otherwise impassable.

The pace of paving projects picked up in the 1840s, and by 1849, cobblestone pavement had become widespread. Then, in 1864, Detroit saw its first stretch of woodblock paving.

Wooden pavement had its drawbacks. The lifespan of a woodblock street—best-case scenario—was about ten years. But on a heavily traveled road, it might be more like two or three. Moisture from the rain or other less pleasant elements—horse urine, for example—soaked into the wood, making it liable to rot and reek. Really reek. Also, it was flammable.

Lithograph advertisement for Flanigan’s Asphaltic and Wood Pavement. Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

But the wood was said to be better than stone at muffling the sound of horse hooves and carriage wheels (and smoother for both carriage and horseback rider). And with a natural abundance of lumber in the region, wood paving was cheap. Throughout the 1870s, due in part to some corrupt municipal contracts for lumber lobbyists, there was “almost a mania for wood pavements.” Detroit’s serviceable stone-paved streets were torn up and replaced with creosote-treated cedar blocks.

By the 1880s, Detroit streets were once again in deplorable repair. And they were still crowded—they had never ceased to be crowded—with an even broader abundance of traffic: pedestrians, carriages, horse carts, horse-drawn streetcars, omnibuses, taxis and, more recently, bicycles and early prototypes of the automobile. And I’m pretty sure people were still racing horses.

Wrote one witty observer in the Detroit Post:

Detroit has no street signs—that is, no signs with the names of the streets painted upon them. But Detroit has signs of streets. A rough, rotting, unrepaired pavement full of holes, such as jars and rattles the life out of a fine carriage to go over it faster than a walk, is a certain sign of a Detroit street. A lake of thin, slippery mud, caused by excessive sprinkling, sending up a continual steam of disease-breeding reek, spoiling the bottoms of ladies’ dresses and covering the polished shoes of gentlemen with filth, is a sure sign of a Detroit street. A driveway, nearly half of which is obstructed by piles of brick and building material, and half of the rest by loading and unloading wagons, is another sign of a Detroit street. A passage for teams where everybody digs up the pavement at pleasure to fix a gas or water pipe and puts it down again so as to leave either a hillock or a hole, is another sign of a Detroit street. Utter darkness of nights for two to four blocks, with nobody knows how many holes, piles of rubbish, or other obstructions there may be in the way, so that he has to depend solely upon the intelligence of his horse, is a very common sign of Detroit streets. And finally, to meet with a lost stranger every two or three blocks who stops one to inquire his way, is another continual sign of Detroit streets.

The first woodblock paving projects began in 1845. By the 1870s, there was “almost a mania” for wood pavement. No. 33 Center Street, Detroit, Michigan. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection, reproduction no. LC-D4-42944.

Ultimately, it was the bicycle craze of the 1890s (with some help from that “Idol of the People,” Mayor Hazen S. Pingree) that turned this bad situation around.

Rough drafts of the modern bicycle were available in the 1870s, but they were suited for only the sturdy and the brave: your options were the bone-shaker, a ride that rearranged your insides with its rigid cast-iron frame, hard-to-steer front wheel and solid-rubber iron-banded wheels, or the high ordinary, that bike with the perilously tall front wheel. You had to mount it with a stepstool. Once you were atop it, the bike went scary-fast, and a rough patch of road was liable to pitch you over the front handlebars.

It was the safety bicycle, introduced about 1885—coupled with the invention of the air-inflated tire in 1888, which provided desperately needed shock absorption—that finally got people out on the streets. The safety looked a lot like the bikes we still ride today, with a rear-wheel chain drive, front-wheel steering, same-size wheels and a diamond frame.

Bicycling permanently changed the way we get around. Cheaper by scores than a horse (no need to feed it, stable it, bridle it or take it to the veterinarian), bicycles mobilized all manner of Americans. They emancipated women from their houses and from their corsets and voluminous skirts, which they traded in for comfortable shirtwaists and bloomers.

Francis Willard, president of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, learned to ride a safety bicycle at the capable age of fifty-three. Then she wrote a book about it, celebrating its “gladdening effect” and sharing the harrows of traffic:

Just as a strong and skillful swimmer takes the waves, so the bicycler must learn to take such waves of mental impression as the passing of a gigantic hay-wagon, the sudden obtrusion of black cattle with wide-branching horns, the rattling pace of high-stepping steeds, or even the swift transit of a railway train. At first she will be upset by the apparition of the smallest poodle, and not until she has attained a wide experience will she hold herself steady in presence of the critical eyes of a coach-and-four. But all this is a part of that equilibration of thought and action by which we conquer the universe in conquering ourselves.

A young woman, comfortably dressed in a knee-length skirt, with her safety bicycle. Howell, Michigan, 1910. Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

In Detroit, the bicycle changed the streets themselves. By the 1890s, bicycles were causing as much if not more congestion than any other source of traffic on Detroit’s roadways. Wrote Florence Marsh in History of Detroit for Young People (a loveable gem of early Detroit history):

The city streets were crowded with men, women, and children on wheels…Cass Avenue was so crowded with wheels after dark that the street twinkled with the tiny headlights and the air was filled with the clanging of bicycle bells. Foot passengers waited in vain for a chance to cross the road.

Cycling advocates founded the Detroit Bicycle Club in 1879, but “[t]here were only a few men who rode bicycles at that time, [and] membership did not exceed twenty,” wrote Robert Ross in Landmarks of Detroit. In 1880, bicycle activists, enthusiasts and advocates across the nation founded the League of American Wheelmen. Chief among their interests: fixing up nasty old streets so cyclists both avid and casual could use and enjoy them.

The league launched the Good Roads movement, which publicly demonstrated for road improvements, published literature (including Good Roads magazine), backed political candidates who supported internal improvements and rallied support from the news media.

In 1890, the Detroit Bicycle Club merged with the Star Club to create the Detroit Wheelmen, a chapter of the national league. Its combined membership of 150 made it one of the largest clubs in the country. When Hazen S. Pingree was elected mayor in 1889, improving Detroit’s streets was at the top of his agenda. In six years, Detroit had some of the cleanest, most pleasurable asphalt-paved streets in the nation.

Bicycle use declined when the automobile came on the scene in the early twentieth century. The motor vehicle was a natural outgrowth of the bicycle. Early automotive prototypes, such as Henry Ford’s quadricycle, were essentially bicycles with engines on them, and some car pioneers, like the Dodge brothers, were in the bicycle business first. And once the automobile came of age, it had smooth, well-kept roads to make use of. For the Motor City to exist, we needed that motorless two-wheeled wonder, the most efficient mode of transportation ever invented, to pave the way.