HOUSE, LANDLORD, SHOP,

INSIDE, UPSTAIRS, DOWNSTAIRS

IF YOU STAND in the street today to take a good look at Charles Dickens’s first London home from the outside, you notice first of all that it’s quite tall. There’s a basement below the street-level shop, and three storeys above it. The house is also rather wide, being three windows across. It’s a Georgian row-house, what Londoners would now call an end-of-terrace, not so grand in its dimensions as the fine houses in Bloomsbury, or those further west in Harley, Wimpole, and Welbeck Streets, but emphatically not a mean house. This house was home to the Dickens family twice: when Dickens was a child between 1815 and 1817, then again between 1829 and 1831, when he was in his late teens, and earning his living in London.

No. 10 Norfolk Street stands on a corner, facing into what is now Cleveland Street. Its side flank around the corner has a wide area of wall above the side shop window, and a single window on each floor near the rear of the building looking onto Tottenham Street. In this chapter we’ll look at what can be discovered of the history of the house, meet the landlord, and learn a little about him, and then we shall enter the front door and have a look around inside.

FIGURE 13. Dickens’s old home and the adjacent Georgian shops, looking south towards Charles Street (now Mortimer Street). Mr Dodd’s bow shop window is in the immediate foreground. On the far side of the house front door, the next shop, Taylor’s Buttons, with the circular sign, was Mr Dodd’s ‘back’ parlour. Above them the house is three windows wide. The railed area allowed natural light down to Mr Dodd’s basement kitchen, but the lodgers’ kitchen (below the button shop) remains very dark because the great flagstone under the parlour window has only the original iron grating listed in the 1804 Schedule. Mr Dodd’s corner house and the next three houses occupy the wider part of the vacant wedge of land shown on the Horwood map. Photographed by the author, 2011.

The front door on Cleveland Street has a neat Georgian doorway, designed for an earlier, more slender silhouette than the Victorian crinoline. The little fanlight looks old, but the number 22 in the glass probably dates from the 1860s when the separate naming and numbering of Norfolk Street disappeared, and this part of the road was merged with the rest of Cleveland Street.

The six-panel front door looks old too, despite having lost its original furniture. The area was inhabited by numbers of medical students long before there was an officially established medical school at the Middlesex Hospital, and Victorian medical students were notoriously rowdy; for some obscure reason they seemed to think it fun to wrench door knockers from street doors, so perhaps it’s not surprising that only one door in the street seems to have anything resembling original door furniture.1

To the right of the house door, a small domestic window starts at about hip-level, which brought daylight to the shop’s parlour, placed at the side rather than at the rear of the shop because of the curiously shaped site this house occupies. This room is now a small and delightfully quaint button shop, quite separate from the café, which currently occupies the corner. It is run by a lady called Mrs Rose, and is lined from floor to ceiling with shelves piled high with little boxes, each with a button attached outside, to show its contents. The shop feels curiously ancient, as though it’s been there for ever, and reminds Dickens-lovers who have seen it of Mr Pumblechook’s seed shop in Great Expectations, of which Pip thought: ‘He must have been a very happy man indeed, to have so many little drawers in his shop.’2

FIGURE 14. The corner house at 22 Cleveland Street (10 Norfolk Street). Originally Mr Dodd’s corner shop, and Dickens’s old home. From this direction, the entrance to Mr Dodd’s shop and his side windows on Tottenham Street are visible, as well as those of the three upper storeys. Photographed by the author, 2011.

To the left of the front door the building has a very large bow-fronted shop window, which curves round in a wide shallow arc to the shop door at the corner. This great window was probably originally a typical Georgian shop window: composed of many smaller panes of glass, and supported by a curved grid of glazing bars. The same is probably true of the other large shop window round the corner, which faces onto Tottenham Street, but there is no sign that that one was curved.

The character of the house finds echoes in the design of the adjacent run of three Georgian shops, which lead south towards what used to be Charles Street, and the front of the Middlesex Hospital. Each has a similarly wide bow-fronted shop window with classical denticulated detailing along the top, and separate doors for shop and house. Each looks originally to have had a railed area at the front for light and access to the basement, which survives in three of the four, though their railings are assorted.3 The houses in this little row are in various states of repair, and are painted various colours, but they have a kind of unity of dimension, style, and detail which suggests that they may be the work of the same builder. Who that builder was isn’t certain, but their history is curious and offers clues to who it might have been.

This little group of Georgian shops is all of a piece, originally Nos. 7 to 14 Norfolk Street, later additions to the rest of the street, being afterthoughts. Old maps show that they were individually designed to fit on a curiously wedge-shaped piece of land on the east side of Norfolk Street which straddled Tottenham Street, left vacant when most of the houses on both side streets were already built. The older houses at the rear—on what is now Goodge Place—and others infilling the land on the St Pancras side of the boundary, were on land belonging to a different owner: the Goodge estate. Several had windows or gardens running tight up to the parish boundary behind Norfolk Street.

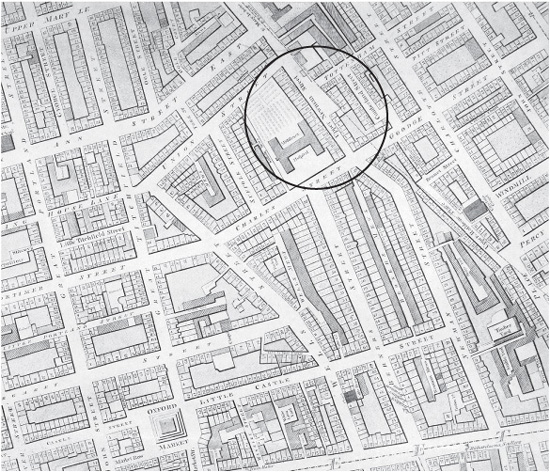

FIGURE 15. Horwood’s Map of London, 1799, showing the ‘H’ block of the Middlesex Hospital and its garden, and the southern wing of the ‘H’ block of the Workhouse (centre top). The fields of Rocque’s map had already disappeared under streets and houses, but the old field boundaries are often still discernible in the street-plan. Oxford Street runs along the bottom of the map, and Tottenham Court Road clips the corner at the top right. The wedge of land on which Dickens’s future home would be built is still vacant, between the east wing of the Hospital and the estate/parish boundary, which runs top left to lower right. Norfolk Street was still regarded as a northern branch of Newman Street at this date. Richard Horwood, Cartographer, 1799.

The vacant wedge of land, by contrast, was on the Marylebone side of the boundary, and was part of the Berners estate. For some reason—perhaps from some disagreement concerning access rights or light—this wedge of ground had been left empty when the rest of the block was built. Yet it must have possessed considerable value. A large folded parchment deed survives in the archives concerning the smaller northern half of this site.4 It shows that in the 1790s the thin end of the wedge above Tottenham Street was sold by Charles Berners to developers John Johnson and William Horsfall, the second of whom was a local builder who lived on the opposite side of Norfolk Street, and who had workshops in a mews on Tottenham Street.5 In the deed’s margin is a tiny sketch plan of the plot of land, with its detailed dimensions. It shows it was widest at the south, but that above Tottenham Street it tapered sharply to less than six feet in depth. The houses eventually erected on it had street frontages as wide as those that remain, but there was so little depth to the site that it seems curious they were ever built at all.

These peculiarly shallow houses have all since disappeared; in the twentieth century their site was absorbed by a large building which juts into the pavement on Cleveland Street south of the Workhouse wall, following the outline of the old wedge of land. The pavement on Cleveland Street at this point still exhibits a shallow bend to accommodate those extra six feet, and this bend marks the historic northernmost tip of Norfolk Street.

It seems likely that the men named in this old deed were also responsible for building the four houses which still stand on the wider part of the wedge of land, including the corner house in which the Dickens family lived. Sadly, every single one of the other houses on Norfolk Street, which pre-dated them, has disappeared, leaving only this late cohort of four Georgian houses as the only remnants of the street Dickens knew.

The odds against their survival were high, especially when we consider that besides the expansion of the Middlesex Hospital—which removed the opposite side of the street—and the encroachments of twentieth-century property ‘developers’, which took the rest, there has also been the London Blitz, when bombs rained down all around. Second World War London Bomb Damage maps show that bombs fell in a line up Charlotte Street, the next street along, at Goodge Street, Tottenham Street, and Howland Street, and that a landmine obliterated Whitfield’s Tabernacle on Tottenham Court Road, including its vaults where that ‘celebrated fanatic’ Lord George Gordon (instigator of the Gordon Riots, the central theme of Dickens’s novel Barnaby Rudge) had been buried, and decimating its churchyard monuments.6

But the old house that Dickens knew has endured. Despite the destruction and change evident all about, from this house and its few neighbours we can try to visualize the street as it was, and be grateful for the enormous good fortune that these modest Georgian houses, and most especially the one on the corner, have survived.7

The Dickens family’s landlord at 10 Norfolk Street was a cheesemonger and grocer: Mr John Dodd. Little is known about him or his family. We do not know how the Dickens family found Mr Dodd, but there may have been some family or other contact which put them in touch with one another—one seeking tenants, the other seeking an affordable home in London. It’s possible that Dickens’s relatives in Berners Street knew him, or that he was a supplier to William Dickens’s coffee-shop, or that other mutual friends lived nearby.

Mr Dodd had been settled in Norfolk Street for over a decade when the Dickens family arrived in 1815, and was still there during and after their second stay in the 1820s. Records fix him at that address for over twenty-five years between 1804 and c.1830. Not much is known about him, but there is a strong possibility that he was local to Marylebone as a boy.8 If this was the case, it could mean that John Dodd and John Dickens had known each other since their schooldays. Later, in 1824, when John Dickens was imprisoned in the Marshalsea Prison, Mr Dodd was one of John Dickens’s creditors, so it looks as though the Dickens family had not paid him all the rent they owed him from living in Norfolk Street when Dickens was a child. But it is also known that Mr Dodd was not responsible for triggering the proceedings against John Dickens, which were begun by a Camden Town baker to whom John Dickens owed £40.9 Furthermore, in the later 1820s, Mr Dodd took the Dickens family back into his home for a second time after they had been incarcerated in the debtors’ prison and after they had been evicted from their home in Somers Town. So it appears that he was a forgiving landlord, and perhaps a good friend.

It may be that this kindness contributed to Mr Dodd’s own rocky financial times, as he was himself nearly bankrupted in 1816, and fully so in 1825. We do not know what caused his first crisis, which looks to have occurred while the Dickens family were living in the house.10 In the second instance, Mr Dodd’s difficulties may have been precipitated or exacerbated by the failure of a bank. A banking crash in 1824–5 forced the closure of nearly eighty banks, and many people lost their entire savings. I have found evidence which shows that Mr Dodd lost the sum of £101 (twice the annual rateable value of his house) in the crash of a local bank, in which his savings were lodged. He may well have lost other money he had carefully saved elsewhere.11

Dodd is not a rare name, even within the confines of the parish of Marylebone, and it has been devilishly hard to try to work out anything about Mr Dodd more personal than his money problems. Henry Dodd, the ‘refuse collector and philanthropist’ (and would-be patron of decayed actors), who much later became the model for the ‘Golden Dustman’ in Our Mutual Friend, is not likely to have been of the same family, but Dickens may have been well disposed towards his name when they became friends in the 1860s.12

There are tantalizing hints of the possibility of connections in the local arts world: but it is not known as yet if John Dodd was anything to do with Mr Dodd the famous singer, who had entertained visitors a generation earlier at Drury Lane Theatre and in the open air at the Marylebone Gardens, with Garrick’s song from Harlequin’s Invasion:

Thrice happy the Nations that Shakespeare has charm’d

More happy the bosom his genius has warm’d

Nor do we know if the Dodd brothers, famous for their violin bows, who made musical instruments and sold harps in Berners Street, were associated with him.13

When Mr John Dodd of 10 Norfolk Street was listed for bankruptcy in 1816, the official London Gazette described him not only as a cheesemonger, but also as a dealer and a chapman.14 The description ‘dealer’ is unfortunately too vague to be helpful: it simply means that he made deals in goods other than cheese; but a chapman is more specific—Mr Dodd sold cheap literature. Of course we have no idea how extensively he traded the little books called chapbooks, or what sort of chapbooks they may have been.15 The range of cheap books available for purchase in Regency London was very wide, from children’s books of nursery rhymes, fairy tales, or alphabets and reading primers, to reading materials for adults who could not afford bound books: almanacks, stories of shipwrecks, murders and other crimes, letter-writers, fortune-tellers, or dream interpreters, caricatures, religious or political pamphlets, or moral tales such as the ‘Cheap Repository Tracts’ designed to suppress political activity among the poor.

Chapbooks were made from one large sheet printed on both sides, folded in half several times down to a smallish booklet, sewn across the final fold and the edges cut to make the pages. They invariably had an interesting woodcut illustration or a loud exclamatory headline on the front cover to attract attention. Some of Dickens’s earliest reading matter may have been chapbook versions of traditional tales like Dick Whittington, Robin Hood, Aladdin, and Cock Robin, novels abridged for children’s reading such as Gulliver’s Travels, Moll Flanders, or Robinson Crusoe, comic alphabets or little books of songs, jokes and riddles, or London cries.

To ponder what illustrated books and chapbooks, or indeed pictures, Mr Dodd might have had about the shop and inside the house, or perhaps framed on the stairs, leads to another realization: that Norfolk Street stood in a district rich in printed, painted, and sculpted imagery. Just to the south, Berners and Newman Streets were well known as a hub of artistic industry. Dotted along Charles Street and around the cluster of small streets surrounding the Middlesex Hospital were the workshops and studios of artists, sculptors, picture-frame carvers and gilders, engravers, lithographic and copperplate printers, wood engravers, and skilled tinters of finished prints.16 The famous sculptor Nollekens was living just round the corner on Mortimer Street when Dickens was a child, as renowned for his miserliness as for his tombs.17 On the next corner up from Mr Dodd’s shop, past the Workhouse, was another sculptor’s studio. The men who worked there—the Gahagans, father and son—made busts, and standing statues, and small maquettes, many blackened to look like basalt—Nelson, Wellington, George III, all gazed out with their blank eyes, and amid the dust and straw of the studio, one might have seen hands and feet in stone or plaster lying about waiting to be fixed to their bodies.18 There were also musical instrument makers, piano tuners, timber yards, timber benders, cutlers, all sorts of practical workers, as well as oil and colourmen selling paints and sundries for artists and carvers, and for the scene painters at the theatre on Tottenham Street.

A much stronger connection with the art world is with the artist Philip Augustus Gaugain, son of a family of engravers, who gave 10 Norfolk Street as his studio address on a number of occasions when he exhibited at the Royal Academy and at the British Institution in the early 1820s, between the Dickens family’s two stays there.19 There was also a dynasty of Dodds who worked as artist-engravers in Marylebone.20 If John Dodd was related in some way to these engravers, there’s a possibility that he owned some of their work, and that as a child Dickens might have seen the lad climbing into a waggon from Roderick Random, or the Fatal Bridge from the melodramatic production of the Blood Red Knight at Astley’s Amphitheatre, or even more mournful images, such as the poor prisoners near Newgate after the Gordon Riots, from the Newgate Calendar.21

As a child, Dickens might have been aware of the artiness and the busyness of the creative industries of the area only at a marginal level, but the visuality of his perceptions suggests that he could well have been interested from an early age in the pictures displayed in shop windows, or for sale in boxes or portfolios out on the street.

Just a little way up the road at No. 9 Cleveland Street, for example (directly opposite the Workhouse), was the printing workshop of Thomas and William Daniell, artists and prolific aquatint etchers, famous not only for their Picturesque Voyage to India by way of China—accurately recording Chinese and Indian landscape and architecture (like the Taj Mahal) with the precision of the camera lucida—but also for fine views of London from the River. Some of their work is likely to have been displayed in the shop window.22 William Daniell began his most famous work, A Voyage Round Great Britain, just before the Dickenses moved in with Mr Dodd, and was busy etching and printing the plates from the first tranche of his great coastal survey from Land’s End to Dundee via Holyhead. His press room may perhaps have been visible to passers-by from the street. The work on this huge project—which resulted in a splendid set of 308 etchings in eight volumes, and took in the entire circuit of the coastal topography of the British mainland—continued through the Dickens family’s first stay in Norfolk Street, and beyond.23

Just around the corner from the Daniells, the entire Landseer family was living and working at 33 Foley Street, which branches off Cleveland Street opposite the Workhouse. A series of exceedingly beautiful prints of human body parts by Edwin Landseer (then training under Benjamin Robert Haydon) was printed and published by John Landseer from that address between 1814 and 1818, while Dickens was living in Norfolk Street.24 In Tottenham Street, the street onto which Mr Dodd’s other shop window faced, were the premises of at least two other important picture printers. When Dickens was a small boy, the Havells—world-famous now for their spectacular series of over 400 coloured aquatints of Audubon’s Birds of America—were creating a fine series of coloured vignettes of historic English costume and architecture, some by Dickens’s future cousin by marriage, Richard Cattermole.25 Another printer on Tottenham Street was John Dixon, known for his large mezzotint portraits like that of the great actor David Garrick, and society beauties like the Crewe sisters (the employers of Dickens’s grandmother).

While the Dickens family was living at 10 Norfolk Street, Dixon had been creating smaller etchings, of Waterloo (by Thomas Bewick’s pupil Luke Clennell) and scenes from most of Shakespeare’s plays.26 It is not known if the porcelain figurine of David Garrick in the actor’s most famous role as Richard III, which was based on Dixon’s print of him, was actually on sale in the Staffordshire chinaware shop round the corner in Cleveland Street, or indeed, if it had been inspired by prints on display in Tottenham Street.27

There was probably a brisk market for theatrically themed goods in the vicinity, because of the well-known theatre on Tottenham Street, which, when the Dickens family first lodged in the area, was called the ‘Regency Theatre’.28 The theatre features in an 1802 cartoon by Gillray of an irate Sheridan—dressed hilariously as Harlequin—followed by other legendary actors invading the theatre when aristocratic amateurs calling themselves the ‘Pic-Nic Club’ took over the place for their own shows, attracting wealthy friends away from the regular theatres.29

Originally, the theatre had been ‘The King’s Concert Rooms’, a concert hall specializing in ancient music, and numerous musical instrument makers continued to work in the surrounding streets. A view of the theatre’s interior in 1817 shows its auditorium to have been modest in size, with benches for the audience in the pit, boxes, two balconies, and people leaning over a bar in the ‘gods’ above, watching a scene from Othello.30 We do not know for certain if Dickens was taken there as a child but it seems quite a likely possibility, and he would have seen the printed playbills and the place so even if he didn’t enter, he would probably have been intrigued by it.31

The presence of all this vibrant engraving and printing in the immediate area of Norfolk Street leads to the hope that somewhere there may exist a more prosaic production of the printing press: a butter-paper from Mr Dodd’s shop. London grocers often had their own personalized papers for wrapping the butter and cheese they sold.32 Such ephemeral things are extremely elusive, and relatively few examples of them survive, so one from Mr Dodd’s shop may never be found. But if such a thing existed, it might perhaps have shown the shopfront as it then was, with Mr Dodd’s name in large letters, his address less prominently, some swags or flourishes, and perhaps a list or an illustration of the things he wanted customers to know about his stock-in-trade.

FIGURE 16. Butter-paper from the shop of John Wrigley, Grocer. Artist unknown.

Other cheesemonger-grocers enumerated a considerable array of goods on their papers—these were not shops containing only a variety of fresh and smoked cheeses: they also dealt in fresh butter, eggs, cream, sausages, poultry, fresh lard, and also preserved or smoked meats such as bacon and hams, as well as traditional baked pork pies and cold pies with other fillings. They often also sold other provisions which did not deteriorate quite so swiftly: dried goods like teas, coffee, cocoa, and sugar, dried or crystallized fruits, ginger, nuts, rice, pulses and grains, bottled jams and marmalades, as well as sauces, salted and pickled fish, pickles and other relishes, spices, treacle, oils, and vinegars. Some grocers sold starch and laundry blue. A considerable part of a grocer’s stock might also be in bottled drinks—wines, ales, cider, ginger ale, soda water, lemonade, and barley water. We do not know how extensive Mr Dodd’s stock might have been (bearing in mind that some shops were quite sparsely stocked) or whether he served, as some grocers did, as a wholesaler, or if he dealt in stationery, books, or newspapers alongside his chapbooks, sold confectionery, tobacco, or snuff, or if he had other sidelines.33

How Mr Dodd navigated being landlord to the Dickenses and surviving near bankruptcy during the two years they were first living in the house is not known. When Dickens’s father was later under pursuit by creditors, he went to ground, disappeared to other lodgings, suffered the indignity of being shouted for in the street, and he was also arrested and locked up in what was known as a ‘sponging house’, a sort of private holding facility for arrested debtors, in Cursitor Street, off Chancery Lane. We simply do not know whether Mr Dodd had to flee his shop, or saw his stock impounded by bailiffs. The Dickenses were lodgers, and almost no documentation survives for the period, but it is possible that the shop was closed, or kept running by a loyal assistant, or managed by means of a ruse—in the name of Mr Dodd’s wife or a friend, for example. All we have to go by at the moment is that in the February of 1816 Mr Dodd’s imminent bankruptcy was announced in the press.34

Yet it is also clear that Mr Dodd traded from the same shop long afterwards, so he must have been able to raise the money to clear his debts relatively swiftly. These crises suggest that Mr Dodd could have become inveigled into extending himself—perhaps laying out on stock—from greater creditors. Possibly he had clients to whom he had delivered goods, who had failed to pay, which was a constant headache for all London shopkeepers and craftsmen, including even Lord Byron’s coach-maker.35

It may have been a misfortune of another kind that caused Mr Dodd’s difficulties. Prosecutions by grocers during this era show that they were often going after untrustworthy staff rather than shoplifters, and although no record of any legal proceedings by Mr Dodd has yet been found, we do not know if such might have been the case: it may be that he was too kind to prosecute. Nevertheless, to have survived as a cheesemonger, grocer, and chapman on the corner of Norfolk Street for a quarter of a century suggests that John Dodd was an able shopkeeper, and that he had a loyal clientele.

London grocers frequently used as a shop sign the conical solid old-fashioned sugar loaf, or a tea canister, and had a custom of standing tea-chests (which in those days had Chinese lettering) outside the shop. Unlike many other shopkeepers—such as greengrocers, furniture brokers, pawnbrokers, or linen drapers—a cheesemonger might not have the opportunity to display goods outside for fear of theft, perishability, and street dust, so Mr Dodd’s two windows on the corner were probably important to attract customers inside. It is most likely that for the display of fresh cheeses Mr Dodd would have used the shaded interior of the shop, while the Cleveland Street window (which receives some direct sunlight in the afternoon) would be suitable for lighting the interior, for publicity, and perhaps for the display of bottled and packeted goods less easily spoiled by exposure.

The window displays of this era are an under-researched area, but shelves inside the bow-fronted window probably created a little shade, and allowed the display of imperishable objects—such as a display of boiled eggs in straw to look new-laid, or baskets or stacks of mock cheeses—as well as small tableaux of farm folk or mandarin figures, pot plants, or notices in some of the panes of glass promoting the goods sold. The adult Dickens seems to have had an interest in advertising and billboards, which may date from exposure to Mr Dodd’s window-dressing.36

Life for a cheesemonger in the days before refrigeration probably focused to an extraordinary degree on the storage and preservation of perishable goods, and would have entailed care in their protection from London dust, and the constant cultivation of coolness. A through-draught would have been valuable in summer, less welcome in winter. Flies (especially as there were stables across the road in the mews behind Tottenham Street) and, doubtless, mites and mice were also attracted to the food, and there would have been odours in the hall and rising upstairs: mixed odours of freshness and rancidity, of cheese and smoked bacon—that slightly fusty smell one can still encounter in small delicatessens, despite refrigeration, but to a more concentrated degree.

Even within living memory, stone or glass slabs and damp butter-muslin cloaking cheeses were the stalwarts of the cheesemonger for coolness. Fresh leaves or cut paper were probably used for platters under cheeses, and other paper wrappers used for cones or twists of sugar or salt, tea, and other dry goods. Cheesemongers were evidently also known to utilize recycled paper, as there is a story that one of Dickens’s favourite actors, Charles Mathews, was able to obtain some manuscript letters of the playwright Sheridan from a colleague who had discovered them among a heap of manuscripts sold as waste paper to a cheesemonger.37

We do not know if Mr Dodd or his corner shop had any profound influence upon Dickens’s imagination, as it may have done in its owner’s love of order and his entrepreneurial and presentational flair. But we do find Dickens occasionally employing grocerly imagery, which catches the attention. Might the badging and ticketing of Oliver as a pauper infant, which I discuss later in the context of pawnbroking, derive or share something from the date/source derivation of pickles, cheeses, and other foods, wines, or the stock-taking of deliveries? In Barnaby Rudge, a vast cheese is the emblem of John Willet’s hospitality; in Pickwick Papers, Dr Slammer’s bottled-up indignation effervesces from all parts of his countenance and Mr Pickwick pauses, bottles up his vengeance, and corks it down. David Copperfield’s lessons in arithmetic are conducted in cheeses: ‘If I go into a cheesemonger’s shop, and buy five thousand double-Gloucester cheeses at fourpence-halfpenny each, present payment.’ The most memorable of these images appears in Oliver Twist, when Dickens takes a moment out of the narrative to employ streaky bacon to describe dramatic practice:

It is the custom on the stage: in all good murderous melodramas: to present the tragic and the comic scenes, as in regular alternation, as the layers of red and white in a side of streaky, well-cured bacon …. Such changes appear absurd; but they are not so unnatural as they would seem at first sight. The transitions in real life from well-spread boards to death-beds, and from mourning weeds to holiday garments, are not a whit less startling.38

Food and drink, and shopping for them, are so essentially domestic and general that it is impossible to assign their many appearances in Dickens’s fiction to his having lived above a shop. Yet several of these images are hardly domestic slices or cut measures, rather wholesale items, great cheeses and sides of bacon; it’s the scale that suggests they maybe derive from cheesemongery.

Another image which haunts, when one ponders what it might have been like to live in a food shop—especially in a street by a workhouse—is one in which Dickens describes ‘pale and pinched-up faces hovered about the windows where was tempting food; hungry eyes wandered over the profusion guarded by one thin sheet of brittle glass—an iron wall to them’.39

A comic print of 1828 by Henry Heath in the British Museum collection shows the interior of a cheesemonger’s shop, with the counter at right-angles to the front window, much as it probably was in Mr Dodd’s shop.40 A rather gaunt boy has come in with a badly chipped plate, asking for two penny’s-worth of scrapings. The well-fed shopkeeper, just patting some butter into shape, looks askance at the boy—but for us it is the rest of the image that is revealing: the cage-basket for eggs, the shelf in the window bearing goods on display, great cheeses on other shelves behind the counter, scales and weights on the counter, the shopkeeper’s bright white sleeve-covers and apron, and paper bags (or butter-papers?) on their hook. The companion piece shows a scrawny girl sent out to try to borrow money from another shopkeeper by a verbal ruse and a doubtful promise. The bottle under her apron suggests where the money would go were it to be given, which from the shopkeeper’s expression seems unlikely.

FIGURE 17A&B. ‘What a treat’ and ‘I wish that you may get it’. This delightful double cartoon shows two shop interiors, a cheesemonger on the left, suggestive of the kind of shop Mr Dodd might have inhabited, and an oilman/tallow chandler on the right. The images show the nature of contemporary retail display, and the poverty in London in the 1820s. Note the boy’s badly chipped china, and the girl’s pattens, to keep her feet out of the mud and muck of the streets. Etched by Henry Heath and hand-coloured by unknown artist(s). Published by Gans, London, 1829.

One wonders whether the living was quite as thin as this in Norfolk Street. I doubt that it was—there were plenty of poorer areas in London, and although Norfolk Street was not as wealthy as central Marylebone or Bloomsbury, there was a large middling population in the vicinity, so a trustworthy grocer should have been able to make a fair living. The fact that Mr Dodd kept his shop for so long—despite plenty of competition nearby—suggests that there were good times as well as bad.

The working day would have been long, with early in-deliveries for fresh goods, out-deliveries to prepare and send to private customers’ homes, and, of course, customers visiting the shop. Before the Ten Hours Act of 1847 (which only limited the length of the work day for women and children) working days for everyone were long, so if Mr Dodd wanted to cash in on evening custom, he would have had to remain open late. In one of the Sketches by Boz, Dickens describes a cheesemonger’s shop at night:

the ragged boys who usually disport themselves about the street, stand crouched in little knots in some projecting door-way, or under the canvass window-blind of the cheesemonger’s, where great flaring gas lights, unshaded by any glass, display huge piles of bright red, and pale yellow cheeses, mingled with little five penny dabs of dingy bacon, various tubs of weekly Dorset, and cloudy rolls of ‘best fresh’… It is nearly eleven o’clock, and the cold thin rain which has been drizzling so long is beginning to pour down in good earnest; the baked-’tatur man has departed—the kidney-pie merchant has just taken his warehouse on his arm with the same object—the cheese-monger has drawn in his blind—& the boys have dispersed.41

Mr Dodd might well have provided an indoor welcome in the form of chairs, or—as in the Heath cartoon, an upended barrel—for customers to rest upon while waiting for purchases to be assembled and packaged up, and perhaps while passing the time of day.

The sociality of shops is evident from cartoons of this period, which sometimes feature two- or three-way conversations which include the shopkeeper. The semi-domestic/semi-public interior of shops seems to have partaken of the informality of the parlour, and something of the conviviality of the ale-house without its boisterousness, and is often used in droll cartoons to provoke laughter through comment on the times. If Mr Dodd was a witty or a friendly shopkeeper, conversations and laughter may often have been audible on the house stairs. If the Dickenses purchased ingredients for their suppers from him, commentary on national affairs as well as local news would have passed upstairs, too, just as they would in conversations had by Mrs Dickens or the family servant elsewhere in the house, or elsewhere in the street.

The permeability of the house might also have been a problem, in terms of interlopers. Mr Dodd would have had to keep a sharp eye on the interconnecting door to the hall, which led up and down to the rest of the house. Burglary was a common problem in London, and opportunist thieves as active then as now: a corner shopkeeper would have to be alert, or he might find his home and lodgers robbed.42

Looking at the rest of the house from the inside, we find that in the basement below the shop and parlour were two kitchens, one of them fairly extensive. How much of the produce that may have been sold upstairs in the shop (like baked pies and pickles) was actually made on the premises isn’t known, but it’s likely that the larger of these kitchens was designed to serve the shopkeeper and his household, and the smaller the lodgers on the upper floors.

It’s genuinely a surprise how much can be deduced about the inside of 10 Norfolk Street, and not only from the building as it survives. At some time in the mid-twentieth century, a kind archivist at the British Records Association discovered an old inventory listing the fixtures in the house, and arranged for it to be donated to the Westminster Archives. This document, which calls itself a ‘Schedule’, was taken down in 1804, in a beautiful clear longhand script. It names Mr Dodd, and specifies the location of his house on the corner of Norfolk and Tottenham Streets.43 As you read, it’s not difficult to imagine the assessor passing through the house looking attentively at everything, even the bolts and latches on the doors, choosing the appropriate terminology, and carefully noting down the details.

The listing goes from the basement methodically upwards to the attics (though sadly missing the final sheet/s) and begins by itemizing the fixed equipment of each kitchen, including a large eleven-foot dresser with pewter-topped shelves, fixed cupboards ten feet tall with strong locks, lead-lined oak sinks, water cisterns with ballcocks, water service pipes, waste pipes, and cooking ranges with sliding spits, trivets, and fenders.

There was a ‘copper’ for laundry in the north kitchen, which was presumably a facility shared by both households. A copper was a curious thing, quite unfamiliar today. We can glimpse one in use in a contemporary Fairburn cartoon featuring Dickens’s favourite clown, Grimaldi, who in the role of a coachman accidentally falls down some steps into an open basement, straight into a barrel of suds, and comes out singing: ‘I laugh’d he!he! he! and the Washer-woman laugh’d ha!ha!ha!’44 The copper is the heavy barrel-shaped object behind the laundress, a brick-built furnace with a fire in its belly (notice the small door and the coal lying by it on the floor), a heavy wooden lid, and a stirring stick protruding from the copper vessel embedded over the fire, which held water for boiling and starching laundry. The famous Cruikshank illustration of Oliver asking for more also features a copper: this one, in the workhouse, was used to heat the paupers’ gruel and soup.45

We do not know who inhabited these basement kitchens. There may have been a cook and skivvy serving the shop and Mr Dodd’s household upstairs, and for the Dickens family a maid-of-all-work who probably spent time down here preparing food and laundering for the growing family upstairs, when she wasn’t minding the children.

FIGURE 18. (Left) The extraordinary Schedule, or inventory, of Mr Dodd’s fixtures and fittings at No. 10 Norfolk Street, many of which survive today. The document dates from 1804.

One cannot fail to ponder whether as a child Dickens found his way down here for breakfast, or for little snacks with the maid-of-all-work, and what conversations might have been had here while pastry was being rolled or pot-herbs chopped, what stories passed on. The smaller kitchen was a dark room even then, because although its tall window opens onto the front yard, at this point the street pavement passes above it on stone slabs, the only direct daylight being provided by an iron grating fixed into the stone, and listed in the Schedule. Another window opens at the back of this room onto the stairwell, but it’s a long way down from the first window on the stairs, and would surely have been gloomy, just as it is now without the lights on.

When I was first researching the Dickens family’s association with the house, I was astonished to find this inventory, and spent some time transcribing it in detail.46 No such document survives in the archives for any other house on Norfolk Street, so we must consider this extraordinary manuscript—like so much that has survived for the history of 10 Norfolk Street—as an unexpected gift from the past. I have been fortunate enough to be invited into the house by the current inhabitants, and can report that quite a surprising proportion of the materials listed in the Schedule can still be found in situ. We went round the house with the transcript, and as I read it out loud, we looked about us. All of us had an extraordinary feeling of the past flooding through the words.

FIGURE 19. Inside No. 10 Norfolk Street: 1. The curved ripples in some of the panes in this slanted partition, mentioned in Mr Dodd’s Schedule of 1804, show it to be probably original hand-blown Georgian glass. Photographed by the author, 2011.

In the basement passage, for example, the Schedule describes ‘a canted partition with door from foot of stairs’ with a glazed panel over it of ‘15 squares’. This door and its upper panel were likely to have been important for preventing cooking and laundry smells and steam rising up through the house. The door itself has disappeared, but the door’s frame remains, exactly as it says, at a slant, at the bottom of the stairs, and remarkably the fifteen panes of glass above it are still there too, some of the glass showing by its curved undulations to be hand-blown and therefore likely as old as the house, despite everything the Luftwaffe dropped on the neighbourhood.

FIGURE 20. Inside No. 10 Norfolk Street: 2. The staircase down to the basement: the original treads of the stairway still in situ. Photographed by the author, 2011.

This passage-way lies under the hallway on the ground floor above, and runs between the two basement kitchens. It leads from the foot of the stairway in the rear of the house to the open area in the front yard, where there is still a locked coal-hole and a water closet (just as there was in Dickens’s day) as well as a lockable vault, under the street pavement. The Schedule lists a large lead-lined water tank, or ‘reservoir’, raised upon York stone supports, presumably operated by gravity and hand-pump to serve the basement water closet and both kitchens as well as the laundry copper and other facilities upstairs: a very important provision in the days before a constant and pressurized water supply.

The two basement kitchens in the house have of course been modernized in the intervening two hundred years, and denuded of most of what was listed for them in 1804. But, as we turned back into the house from looking at the front yard, we saw that the shelves of an old dresser survive in the passage, and although the pewter coverings, and the long work surface listed below it have gone, the deal backing described in the Schedule still survives; and, it measures eleven feet long.

The artist George Scharf, a contemporary of Mr Dodd, painted the basement kitchen in his own home in Francis Street, only a few blocks east of Cleveland Street. The room has similar dimensions to the larger kitchen in Norfolk Street, so the painting provides a good idea of how the kitchens in Mr Dodd’s basement might have appeared at the time.

Scharf’s fine watercolour shows a wide stone-flagged floor with painted matting in its centre. A very long dresser (it could easily measure eleven feet) occupies the longest wall. The woman who worked there stands before it, proud of the neatness and good order of the room. The dresser is loaded with dishes and tureens, willow-pattern serving plates, dinner plates, jugs, and bowls, a cruet, coffee grinder, trays, and other dining equipment, with cooking pots, kettles, a trivet, gridiron, and various sieves stowed underneath. It is quite possible that both dressers in Norfolk Street were used in a similar way.

Looking at this household equipment, one realizes that if the Dickenses had belongings of this kind they had probably been received as wedding gifts, and would be just the kind of things they would have had to pawn when Mr Dickens was later threatened with being arrested for debt. For now, this is the kind of room (and perhaps the kind of inhabitant) with which young Dickens might have been familiar below Mr Dodd’s shop.

FIGURE 21. Basement kitchen in Francis Street, Tottenham Court Road, by George Scharf. This delightful interior gives a good sense of the kitchen of a comfortable middle-class home. Mr Dodd’s and the Dickens family’s kitchens at 10 Norfolk Street may have been more sparsely furnished with movable goods, but might have aspired to something like this. The woman’s pride in the domestic display is evident. Watercolour, 1846.

At the very back of the house in 10 Norfolk Street is a basement room entirely without windows. It lies partly under the stairwell, tucked away behind the smaller kitchen. It is described in the Schedule as a wine vault, with its own door and ‘full warded lock’. It is still the coldest and darkest room in the house, and still has deep apertures set three by three, into the depth of a very thick wall, which the writer of the Schedule described as ‘9 brick catacomb wine binns’.

Cold wine racks are rarely described today as ‘catacombs’, which we associate with the idea of burial. So it is intriguing to think Mr Dodd would have stored his bottled drinks for the shop upstairs (and perhaps some for his own consumption) here, as well as other shop stock which needed to be kept secure and cool.

The stairway up through the house still has its original handrail, and the original sturdy stair treads—thick slices of heavy hardwood, shiny with age and much varnishing—remain in daily use on the first flight of stairs up from the basement to the shop level. They were designed to last in the 1790s.

The Schedule provides a good idea of Mr Dodd’s shop fittings, describing four shelves in each shop window, and window shutters outside. Both inner walls of the shop were furnished with units of multiple shelves supported on ornamental columns, and nests of drawers. One cannot fail to wonder if Dickens was thinking of them when he described the ‘delightful rows of green bottles and gold labels, together with jars of pickles and preserves, and cheeses and boiled hams, and rounds of beef, arranged on shelves in the most tempting and delicious array’ in Pickwick Papers, or the very different ones elsewhere in the same book bearing dummy stock, and half of whose drawers had ‘nothing in ’em, and the other half don’t open’.47

Mr Dodd had three counters, a lockable mahogany writing desk and till drawers. No trace of them remains. The little parlour across the passage, which is now the button shop, had a fireplace, tall cupboards, and windows shutters, all now disappeared, as has the brass doorknocker listed in the Schedule. But the little foot-scraper listed outside still stands.

FIGURE 22. Inside No. 10 Norfolk Street: 3. The staircase up from the kitchens, showing the original handrail. Many other details from the Dickens era survive in the house. Photographed by the author, 2011.

The inventory continues for upstairs, but has less to report. Perhaps the most interesting item is the description of the ‘patent water closet’ on the wide first landing, with its mahogany seat, as it was when Mr Dodd and the Dickenses lived there, with a sink in the separate multi-shelved china closet beside it. This would have been an unusual but crucial facility in the house at 10 Norfolk Street, because unlike most other houses, there was no backyard for the usual London outdoor ‘necessary’, or cesspit. A modern toilet and cupboard now occupy the same landing.

In most of the remaining rooms the listing simply mentions door locks and window shutters, built-in cupboards, and fireplaces with marble ‘slips’ (slabs lining the hearth) firestone hearths, and wooden ‘dressings’ (which I take to mean mantelpieces) but it does not go into details. In almost all instances, these old fittings are gone, but the best room in the house—the first-floor front, what would probably have been Mr Dodd’s sitting room—still has all its window shutters, and a perfect Georgian mantelpiece.

The survival of the Schedule allows us to perceive the house in a very different way from how one might otherwise regard 10 Norfolk Street today. When the listing was noted down in 1804, the house was still quite new—perhaps less than ten years old—and its details help us recognize how very modern and commodious it must have felt when Mr Dodd took it over, with its ornamental shop-fittings and excellent water closets. Ten years afterwards, when the Dickens family first arrived, Mr Dodd was settled in, the shop well established, and domestic arrangements with previous lodgers are likely to have been well worked out.

As one would expect with any London house now divided into separate flats, there has been a great deal of modernizing and obliteration. Yet much survives, and this extraordinary inventory helps us imagine and confirm what Dickens would have known intimately everywhere within this unique London house. One can imagine his child’s hands holding tight on the square balusters as he laboriously climbed up step by step on chubby toddler’s legs, or later, as a teenager racing up the same stairs, two or three steps at a time.