SHEERNESS, CHATHA M, CAMDEN TOWN,

MARSHALSEA, SOMERS TOWN

IT WOULD NOT be an overstatement to say that the interval between the two eras the Dickens family lived in Norfolk Street was one of very mixed fortunes. This chapter bridges the era of Dickens’s life between these periods, so it glances at what happened to him between 1817 and 1829 fairly swiftly, for those unacquainted with the details. Biographers tend to cover this period, when he was aged between 5 and 17, in well-rehearsed ways, because very little first-hand evidence survives for most of Dickens’s childhood and youth, and we are heavily dependent on Forster’s rendering of the autobiographical fragment.1

Neither Cleveland Street nor its Workhouse make much of a showing in this chapter, because Dickens was not living in the near vicinity during these years. But I suggest how, through a series of encounters with other children—a servant, a chimney sweep, and the real Bob Fagin—the young Dickens might have heard about the inner workings of the workhouse system from the point of view of experienced child inmates. Behind these means of access to personal testimony lies his own experience of the family’s imprisonment in the Marshalsea Debtors’ Prison, in 1824.

At the beginning of 1817 Dickens’s father was again posted out of London by his employer, the Navy Pay Office, this time to the naval town of Sheerness, on the Isle of Sheppey, in Kent. Shortly afterwards, the family moved again to the Medway estuary town of Chatham, nearby. The next few years in Chatham, between 1817 and 1822, are generally regarded as the happiest of Charles Dickens’s childhood, being described by his biographer Edgar Johnson as ‘the happy time’.2 These were years when the family was mostly on a fairly even keel, and the boy Dickens read voraciously, explored, and play-acted. Above all, it was a time when he had regular schooling.

During their brief stay in Sheerness, the Dickens family’s sitting room shared a party wall with the local theatre, and the family enjoyed hearing everything through the wall—presumably laughter and applause, even what was passing on stage—and joined in the singing of the national anthem at the end of the shows.3 The gusto with which Dickens’s father later recounted the story of this sitting room suggests a delightful level of enjoyment in the productions—and the absurdity of listening in for nothing. Dickens probably had his fifth birthday in this little house in Sheerness, and its situation doubtless added to his interest in play-acting. The theatre itself was due for demolition, having been leased until that Christmas to the theatrical family of the Jerrolds (friends of Dickens in later life), who had been presenting a wide repertoire, from Shakespeare plays to farces and comic songs. The plays the family heard through the wall could have been theirs.4

The family left Sheerness after only a few months. Until then, Dickens had been educated ‘thoroughly well’ by his mother, and understood some rudimentary Latin before he attended school in Chatham, so it is clear that she was an educated woman herself, and that she passed on a great deal to her eldest son.5 His schoolmaster in Chatham was William Giles, an Oxford-educated Baptist minister. Although Dickens later described his education as ‘irregular and rambling’, the next few years were the best conventional education he had.6 Giles appears to have had high hopes of this particular pupil, hopes which Dickens himself absorbed. Part of Dickens’s subsequent disappointment in his parents was related to their lack of ambition for him when they became mired in their own financial difficulties. It looks as though he had acquired a modest expectation that he might attend a university, and that such ideas had been generated at this school.

Dickens is often thought of as essentially a London author, but it would also be true to say that Chatham, nearby Rochester, and the surrounding Kent countryside flow powerfully into several of his books, not least in the magnificently dramatic and brutal opening pages of Great Expectations, when the escaped convict Magwitch terrifies the young Pip into bringing him food, and a file to cut through his chains. The association of convicts with that part of the Kent coast derives from the Hulks, great old ships moored mid-stream, serving as holding prisons for convicts (most of them from London) destined for forced labour in the dockyards or for transportation to Australia. This punitive presence blended with the culture of the port in the days of the great sailing ships, the swaggering masculinity of the sailors, and the gender politics of the quayside, excitement of tales of travel, the mists and tides of the estuary, and the beauty of the local countryside: all these lie behind Dickens’s memories of this period, which Dickens’s biographer Michael Slater believes to have been profoundly nourishing to his imagination. Dickens’s friend Forster regarded Chatham as ‘the birthplace of his fancy’.7 Chatham is also thought of as a positive time because family income improved again, and domestic arrangements seem to have been good for most of the time. The family was still growing, and the arrival of Mary Weller as the family’s servant and mother’s help looks to have been altogether a positive thing.8 Dickens is said to have based the figure of Peggotty in David Copperfield upon her, and if Mary Weller really was as thoroughly lovable a person as Peggotty, then she alone would account for the happiness of Dickens’s young days in Chatham.

The picture of golden memories with which we are presented, however, does not quite square with Dickens’s later characterization of the Medway towns as ‘Dullborough’ or ‘Mudfog’, and with the bleakness and underlying sense of threat which imbues the Kentish parts of Great Expectations. Perhaps the lustre of the Chatham days was something Dickens appreciated only when he compared them with those which followed.

It was in Chatham that Dickens’s Aunt Mary met and married Dr Lamerte, which was an early moment in the break-up of this happy home. I have always pondered if Dr Lamerte might have been an original for the charming but cold and domineering serial widower Mr Murdstone, in David Copperfield, as Dickens’s aunt lived for only a short while after their marriage. His aunt’s withdrawal from the family may have had an economic impact upon the household as well as an emotional one, because she may have helped financially and probably contributed to the nurture and the education of the children, too. Money difficulties were never far from the surface, even in this era of regular income. The family moved into smaller and cheaper accommodation, and thereafter things probably became even more constrained.

Dr Lamerte’s son by a previous marriage became a lodger in her place, and his enthusiasm for amateur theatricals was of course infectious; but young Dickens suffered later from this fellowship, because it was Lamerte who later recruited him to work as a factory boy. Finances were already rocky when the family left Chatham for London in 1822, leaving young Dickens behind for a short while to finish his school term. Also left behind were debts, which eventually proved disastrous.

Mary Weller having married and remained in Chatham, the Dickens family brought with them back to London a young maid-of-all-work from the local workhouse in Chatham. The name of this young servant is not known, but she remained with the family for some time, and it is said that she was the model for the Marchioness in The Old Curiosity Shop. She was probably very young: working-class girls were often sent out into service at the age of 11 or 12, so she may not have been much older than Dickens himself, who at this stage was 10 years old. We don’t know if this girl was unique among the family’s servants, or whether the Dickens family had employed other workhouse children, nor if Mrs Dickens chose to do so from economy or benevolence: most likely both. As we shall see, it may have been from her that Dickens acquired some of his inside knowledge of workhouse life, and some recognition of his kinship and fellow feeling with the incarcerated poor.

Back in London, and coping again with a drop in pay, Mr and Mrs Dickens and their larger family had now to take accommodation in an area with far fewer pretensions to gentility than Norfolk Street. They found a small house in Bayham Street, Camden Town, which Forster describes as ‘a mean small tenement, with a wretched little back-garden abutting on a squalid court’.9 They now had six children, so the small house was probably very overcrowded.10

At the end of the school term, when Charles eventually joined them from Chatham, it was clear that his parents could no longer afford to continue his schooling. Things cannot have been easy for the whole family, being so short of money, and young Dickens’s life at this time became somewhat aimless. His father, he told Forster,

appeared to have utterly lost at this time the idea of educating me at all, and to have utterly put from him the notion that I had any claim upon him, in that regard, whatever. So I degenerated into cleaning his boots of a morning, and my own; and making myself useful in the work of the little house; and looking after my younger brothers and sisters (we were now six in all); and going on such poor errands as arose out of our poor way of living.11

Many years later, Dickens wrote a delightful account called ‘Gone Astray’, about becoming lost in central London as a child, an experience which seems to date from this period.12 He says he was taken one weekday morning to see the church at St Giles’s—that dangerous district which both frightened and fascinated him. The excursion then extended further south to take in a view of the great stone lion, which in those days looked down from its lofty parapet on the grand old aristocratic palace, Northumberland House, which stood at the top of Whitehall, facing what would later become Trafalgar Square.13

The lion was one of the landmarks of Georgian London, known as the Percy Lion, after the great landed family of the Northumberlands. Lord Algernon Percy is mentioned in Barnaby Rudge, as he had commanded the London militias at the time of the Gordon Riots. Percy Street, which runs south of Goodge Street, took the family name, as did other mews and back streets in the area near Norfolk Street. Behind its wide frontage on the Strand, the great house’s real front faced south, down a grand vista framed by high-walled formal gardens facing towards the wide bend in the River just above Scotland Yard, just to the west of where Dickens would shortly be employed at Hungerford Stairs. The site is now occupied by the broad carriageway of Northumberland Avenue.

Somehow, Dickens tells us, he and his adult guide became separated, and the boy suddenly realized to his own dismay that he was alone. Dickens was writing about this experience thirty or so years later, when he was in his early forties, and a father of ten children himself, when he probably had both a childhood recollection of becoming lost and a grown-up recognition of the panic the adult would also have experienced on making the same discovery. No blame is ascribed to the adult in the case, perhaps from Dickens’s grown-up sense of the inevitability and inexplicability of such events. Something in Dickens’s valedictory tone towards this lost guide suggests that it might have been his father, who, at the time Dickens was writing, had been dead just two years. The biblical resonances of the essay’s title ‘Gone Astray’ would support the idea.14 If true, the story serves to illuminate two oft-quoted comments about Dickens’s education. According to Forster, when John Dickens was asked by a prospective employer where his son had been educated, he replied: ‘Why, indeed, sir—ha! ha!—he may be said to have educated himself!’ presenting an admirable recognition on the father’s part of his son’s independent process of development.15 The description by another father—Tony Weller—of his son’s education has often been taken as Dickens’s own evaluation: ‘I took a good deal o’ pains with his eddication, Sir; let him run in the streets when he was wery young, and shift for his-self. It’s the only way to make a boy sharp, Sir.’16

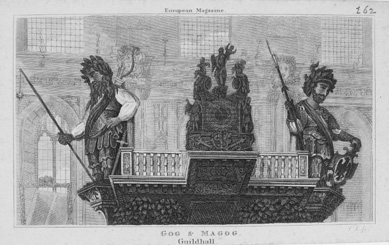

The lost boy was indeed surprisingly resourceful: as the adult Dickens describes it, he found his way along the entire length of the Strand from Charing Cross to Temple Bar, along the whole of Fleet Street to St Paul’s, then via Cheapside to the Guildhall: quite a feat for a child at the age of 10 or thereabouts, unfamiliar with navigating central London alone. There, Dickens reports that he sat in a corner below the giant statues of Gog and Magog, which he already knew by repute as famous sights of the City, and had a rather Chaplinesque encounter with a dog. Altogether, it seems that the boy managed to have an interesting day, only faltering after it got dark, when he sought help from an official watchman, who got a message back to his distraught family.

Besides Dickens’s perception of his own youthful streetwise common sense, the story serves to illustrate the effectiveness of the London watch service before the days of Peel’s Metropolitan Police, and the comparative safety of pre-Victorian London: the boy did not get kidnapped or run over, robbed, stripped, or worse, despite all we have heard about the criminal underworld of London, not least in Dickens’s own works.

FIGURE 24. The great statues of Gog & Magog at the Guildhall 1810.

The Dickens family seems to have been on the slide towards the Marshalsea Prison even before their return to London. Indeed, debts they had left behind in Chatham contributed to John Dickens’s imprisonment. It appears, too, that Dickens’s father still owed money to Mr Dodd in Norfolk Street.17 Before the catastrophe came to pass, Mrs Dickens tried her best to prevent it. She had been hampered from earning money outside the home by the family’s genteel pretensions and by frequent pregnancies and escalating child-rearing duties, but now, with matters looking desperate, she determined to use what skills she had to try to save the family from catastrophe. Towards the end of 1823, she took a better house in Gower Street, and attempted to open a school. The idea was a good one: only a few years later, University College School would open its doors just over the road—and such was its success that it still thrives today.18 Mrs Dickens’s school might also have succeeded, given time and capital: but the family had neither. Dickens was later able to laugh at the predicament inside the family home with creditors shouting loudly from the street, and his mother’s optimism despite the embarrassment of no takers at the school.19 He is said to have been sent hither and yon on sorry journeys to sell and pawn belongings, including even the beloved books. But nothing could prevent his father being committed to the Marshalsea on 20 February 1824, and Mrs Dickens and the younger children shortly joined him there.20

The experience of living inside a Georgian debtors’ prison is conveyed very effectively by Dickens in Pickwick Papers, David Copperfield, and Little Dorrit: the differing character of the two regimes operating within the one institution—one for the abject poor, hopeless of ever being able to earn their way out of debt, and likely to die there; the other for those who could obtain any comfort they desired if they could but find the wherewithal to procure it. Only Mr Dickens was technically the prisoner, so the walls were permeable to Dickens’s mother and the rest of the household when necessary. Above all, the family could be together, even their servant girl could visit, and Charles—who lodged outside—could come in for breakfast and supper.

The family was surrounded by other prisoners, many of whom had very little hope of ever getting out, because the longer they were inside the prison, the less they could earn, the higher their legal costs, and the less likely it was that relatives or friends could raise the funds to save them. Between them, Mr Dickens (who became the chairman of the Marshalsea debtors’ self-management committee) and Mrs Dickens seem to have known everybody in the place. A key nugget of information yielded by Forster from the family’s prison experience is that Mrs Dickens had a knack of getting other prisoners to tell her their life stories. Forster quotes her son as saying: ‘When I went to the Marshalsea of a night, I was always delighted to hear from my mother what she knew about the histories of the different debtors in the prison.’21 This is about as close as we get to real information about Mrs Dickens, towards whom Dickens himself seems curiously ambivalent.22 From it we can appreciate that she was quite as sociable as his father, and that Dickens’s own love of characters and biographies, and his knack of observing and collecting them, probably derives from her relish in them. I suspect the germs of some of his stories derived initially from her.

While the family was in the Marshalsea, Dickens remained outside in lodgings at Camden Town, working during the day at Hungerford Stairs with the tidal Thames lapping round the foundations of the old warehouse:

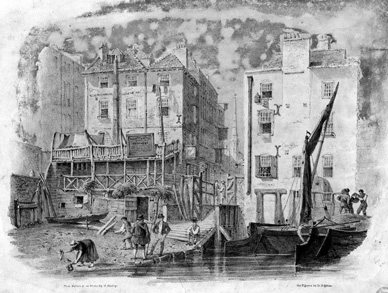

The blacking-warehouse was the last house on the left-hand side of the way, at old Hungerford Stairs. It was a crazy, tumble-down old house, abutting of course on the river, and literally overrun with rats. Its wainscoted rooms, and its rotten floors and staircase, and the old gray rats swarming down in the cellars, and the sound of their squeaking and scuffling coming up the stairs at all times, and the dirt and decay of the place, rise up visibly before me, as if I were there again. The counting-house was on the first floor, looking over the coal-barges and the river. There was a recess in it, in which I was to sit and work. My work was to cover the pots of paste-blacking; first with a piece of oil-paper, and then with a piece of blue paper; to tie them round with a string; and then to clip the paper close and neat, all round, until it looked as smart as a pot of ointment from an apothecary’s shop. When a certain number of grosses of pots had attained this pitch of perfection, I was to paste on each a printed label, and then go on again with more pots. Two or three other boys were kept at similar duty down-stairs on similar wages. One of them came up, in a ragged apron and a paper cap, on the first Monday morning, to show me the trick of using the string and tying the knot. His name was Bob Fagin; and I took the liberty of using his name, long afterwards, in Oliver Twist.23

Dickens walked daily to the factory and back from Camden Town. After he eventually complained of his loneliness and misery there, his parents somehow found him more congenial accommodation nearer the prison:

One Sunday night I remonstrated with my father on this head, so pathetically, and with so many tears, that his kind nature gave way. He began to think that it was not quite right. I do believe he had never thought so before, or thought about it. It was the first remonstrance I had ever made about my lot, and perhaps it opened up a little more than I intended. A back-attic was found for me at the house of an insolvent-court agent, who lived in Lant Street in the borough, where Bob Sawyer lodged many years afterwards. A bed and bedding were sent over for me, and made up on the floor. The little window had a pleasant prospect of a timber-yard; and when I took possession of my new abode I thought it was a Paradise.24

FIGURE 25. Hungerford Stairs seen from the River. This interesting lithograph by G. Harley and D. Dighton was published by Rowney in Rathbone Place, Marylebone, in 1822, in the year before Dickens was sent to work in the blacking factory, which occupied the house on the right. Dickens is known to have played with other boys on coal barges like the one shown in the foreground. His older work-mate Bob Fagin lived nearby with a relative who was a waterman on the River. The spire in the distance belongs to St Martin’s-in-the-Fields. The stairs and the streets nearby disappeared for the construction of Charing Cross Station and Hungerford Bridge.

It is worth observing how easily Dickens slips in the fact that he utilized his own lodgings as the model for his fictional character Bob Sawyer: how knowingly he transmuted what he knew directly into his fictions, and how unembarrassed he is about it. This is a process not at all confined to Lant Street, and it seems to be very widely accepted by Dickens aficionados that Dickens used places he knew in his books. It is clear from his own words that the transcription is more or less direct.

This is part of the puzzle of Norfolk Street. In Pickwick Papers, Dickens mentions the following places by name, all of which we know he inhabited: Gower Street, The Polygon, Somers Town, Little College Street, Camden Town, the Marshalsea Prison, and Lant Street. He also mentions the public house The Fox under the Hill near the bottom of Hungerford Stairs. But the only reference to Norfolk Street that I have been able to find is in his story Mrs Lirriper’s Lodgings, which is supposed to be about Norfolk Street, Strand. None of his biographers have so far looked at the real Norfolk Street from this point of view.

Forster continues with the story:

From this time he used to breakfast ‘at home,’—in other words, in the Marshalsea; going to it as early as the gates were open, and for the most part much earlier. They had no want of bodily comforts there. His father’s income [i.e. his Navy salary] still going on, was amply sufficient for that; and in every respect indeed but elbow-room, I have heard him say, the family lived more comfortably in prison than they had done for a long time out of it. They were waited on still by the maid-of-all-work from Bayham Street, the orphan girl of the Chatham workhouse, from whose sharp little worldly and also kindly ways he took his first impression of the Marchioness in the Old Curiosity Shop. She also had a lodging in the neighbourhood, that she might be early on the scene of her duties; and when Charles met her, as he would do occasionally, in his lounging-place by London Bridge, he would occupy the time before the gates opened by telling her quite astonishing fictions about the wharves and the tower. ‘But I hope I believed them myself,’ he would say. Besides breakfast, he had supper also in the prison, and got to his lodging generally at nine o’clock. The gates closed always at ten.25

This is one of the earliest moments in which Dickens mentions an awareness that he could spin stories out of the air and create astonishment. Dickens’s relationship with this girl (who would probably have been about 13 or so by now)—she to whom these tales were told—spans Chatham, Bayham Street, the blacking factory, and the Marshalsea. We don’t know when she and Dickens had opportunities to talk at length other than during the period when the family was in the Marshalsea, and it seems from Dickens’s account that their relationship deepened in that period. As Forster reports things, these conversations were largely one way: Dickens casts himself as the hero-storyteller, astonishing her. But nothing is said about what this young woman might have conveyed to him.

In Pickwick Papers, and in other places, Dickens posits situations in which people sit together in groups and tell each other stories, as a social activity. So I wonder about the reciprocity in the case of the girl on the bridge; I wonder if there wasn’t also some storytelling on her part. It seems to me quite likely that at some point she might have relayed quite a bit of her own biographical narrative concerning life in the Chatham workhouse, and that its details were heard and absorbed by Dickens, almost as if he had experienced them himself.26 It may be that things she conveyed to him came to mean more to Dickens when he was in the moils of drudgery in the blacking factory, especially if some of the other boys there were parish apprentices, as well they might have been. One can imagine him binding and knotting the jars, mulling things over in some deep part of his mind, possibly allowing him to appreciate that, however bad his own experience, others suffered worse. At least the family was together in the Marshalsea.

Dickens was known at the blacking factory as the ‘little gentleman’, and generally kept himself somewhat socially aloof. But he occasionally played with a couple of the boys on the coal barges by the River. On one occasion, when he had been unwell during the day, Bob Fagin insisted on seeing him safely home:

I got better, and quite easy towards evening; but Bob (who was much bigger and older than I) did not like the idea of my going home alone, and took me under his protection. I was too proud to let him know about the prison, and, after making several efforts to get rid of him, to all of which Bob Fagin in his goodness was deaf, shook hands with him on the steps of a house near Southwark Bridge on the Surrey side, making believe that I lived there. As a finishing piece of reality in case of his looking back, I knocked at the door, I recollect, and asked, when the woman opened it, if that was Mr. Robert Fagin’s house.27

A cluster of associations links Dickens’s experience in the blacking factory with the workhouse, Thames bridges, and a loyal female figure. These associations seem to come to a kind of fruition in Oliver Twist, when the information imparted by a poor girl on London Bridge is a matter of life and death, and associated with a different Fagin.

A single exposure to a child with inside knowledge of workhouse life would have been sufficient for Dickens’s identification with the plight of the workhouse child, and his sure grasp of the institutional atmosphere of the workhouse regime. There were probably other such encounters, including other boys—as I have already suggested—in the blacking factory. It may actually be that Bob Fagin, who was himself an orphan, had spent time in the Cleveland Street Workhouse before being claimed by his brother-in-law, who worked on the river barges by Hungerford Stairs.

There is another instance in which Dickens relates having met and conversed with a workhouse child. In one of his early Sketches, Dickens describes a childhood encounter with a climbing boy: a young chimney sweep. Dickens indicates that they were both about the same age. His lack of fear of the other boy—completely black from head to foot from soot, and standing in his own home—if true, is interesting. The encounter has a quite intimate atmosphere, as though no one else was present:

We remember, in our young days, a little sweep about our own age, with curly hair and white teeth, whom we devoutly and sincerely believed to be the lost son and heir of some illustrious personage—an impression which was resolved into an unchangeable conviction on our infant mind, by the subject of our speculations informing us, one day, in reply to our question, propounded a few moments before his ascent to the summit of the kitchen chimney, ‘that he believed he’d been born in the vurkis, but he’d never know’d his father.’ We felt certain, from that time forth, that he would one day be owned by a lord: and we never heard the church-bells ring, or saw a flag hoisted in the neighbourhood, without thinking that the happy event had at last occurred, and that his long-lost parent had arrived in a coach and six, to take him home to Grosvenor-square.28

The passage demonstrates young Dickens’s curiosity and empathy with the other boy, and (as in the wand story from the Soho Bazaar) the strength and persistence of his desire for resolution to painful human predicaments, for fictional happy endings. Yet, at the same time, in his own adult knowledge, Dickens smiles knowingly at his own hopeless innocence in such hopes. The long afterlife of Dickens’s childlike investment of hope in the other boy’s biography re-emerged in the story of Oliver Twist—not a sweep, but a child almost disposed of as one: an innocent child unfit for the maltreatment to which he is subject, and deserving of something more honourable from those responsible for his fate. When such a point of view is adopted, one can also see that Oliver stands also for Dickens himself.

Dickens acknowledges in the Sketch just quoted that his hope for the boy’s eventual recognition was rooted in a much-repeated London story of the period, an urban legend of child-theft and rediscovery. It concerned a rich lady’s recognition of her own stolen child, who, having been forced to work as a sweep, had descended the chimney into her empty bedroom, and was found by her, exhaustedly asleep in his soot on her pristine bed. The coincidence in this story, which Dickens retells in the same Sketch, and which is well illustrated in the magazine in which it appeared, prefigures that in Oliver Twist, where after the burglary Oliver collapses on the doorstep of a house which turns out to belong to his own long-lost great-aunt/adoptive grandmother.

Long walks from his lodgings to the factory and back took young Dickens daily through the middle of London. Michael Allen’s recent discoveries amongst old records of litigation concerning the blacking business indicate that—dating from Hungerford Stairs and the factory’s move to Chandos Street—Dickens was probably a factory boy for a year or more, perhaps until the autumn of 1824, when he was twelve and a half.29 The work for Lamerte therefore seems to have continued even after Dickens’s father was freed from prison under insolvency legislation, when the family left the Marshalsea at the end of May 1824.

Dickens’s drudgery ended suddenly and unexpectedly, when his father quarrelled with Lamerte, freed his son from the blacking business, and at last sent him back to school.30 The dispute seems to have centred upon the way young Dickens had been set to work with Bob Fagin in the shop window in Chandos Street, often gathering a crowd of onlookers by their dexterity and speed in tying the pots, and doubtless serving as a compelling advertisement for Lamerte’s business. One wonders if it was on this same occasion that Dickens was witnessed at work by Mr Dilke, whose recollection later provoked the writing of the autobiographical fragment, and whether Mr Dilke’s half-crown did not shame John Dickens into perceiving at last what had happened to his own son. Working in the window at Chandos Street may have reminded Mr Dickens of the fate of the debtors on the ‘poor’ side of the Marshalsea, who took it in turns to expose themselves behind a grille which opened onto the street so as to beg for alms from passers-by, although it also partook of the nature of the showmanship for which his son was later so well known.

Although Dickens denied it, he seems to have been decidedly resentful of his mother’s attempt to smooth over this argument with Lamerte:

My mother set herself to accommodate the quarrel, and did so next day. She brought home a request for me to return next morning, and a high character of me, which I am very sure I deserved. My father said I should go back no more, and should go to school. I do not write resentfully or angrily; for I know how all these things have worked together to make me what I am; but I never afterwards forgot, I never shall forget, I never can forget, that my mother was warm for my being sent back.31

For Dickens, this looks to have been something of a parting of the ways (emotionally speaking) from his mother. That reiterated threefold inability to forget, so long into his adulthood, is eloquent indeed. Dickens probably had no notion what his earnings of six or seven shillings a week may have meant to her housekeeping, or what her hopes might have been for him in the world of business, or what it meant to her that a dispute should exist between her husband and her own relations. We know that a decade or so later there was such a serious rift between John Dickens and other members of his wife’s side of the family (the old problem of not repaying loans, it seems) that Charles Dickens wrote letters apologizing for his inability to issue invitations to his own wedding.32 Perhaps Dickens really resented his mother’s concern for that other motherless boy, Lamerte, the stepson of her own dead sister, Dickens’s Aunt Mary. Oliver Twist’s aunt, Rose Maylie, welcomes Oliver into her family as the son of her own dead sister, but that same sister’s older stepson is the vile Monks, the evil genius of the book’s convoluted plot.

When Dickens composed the ‘autobiographical fragment’ from which Forster later worked, his sense of anger was still fierce: so much so, that it appears he was unable to consider that he might actually have gained anything from the blacking factory. His own subsequent success as an entrepreneur, writer, and publisher in the Strand/Covent Garden area however suggests that for all its agony, the experience may actually have been more formative in a positive way than he could bring himself to admit, it having taught him a number of things he might otherwise never have learned so early in life: an appreciation of business practice, manual dexterity and speed, self-discipline, application; an understanding of the importance and value of money and of hard work in getting it; managing on a meagre income (budgeting and paying one’s way); preserving one’s own inner dignity even in the midst of social mortification; learning to recognize and address the humanity of social ‘inferiors’; fitting in to other domestic establishments; recognizing that working lives are often forced and irksome, that terms of employment can be demeaning, and that bare survival is uncongenial; understanding that the cowl doesn’t make the monk and the applicability of that insight to others as to himself; and being able to transform the negativity of feeling demeaned and undervalued into an inner generating force for personal development. For Dickens the whole experience seems to have been thoroughly negative; he was still smarting from it nearly a quarter of a century later. He believed he had been robbed of his childhood.

Dickens had also become immersed in the busyness and the variety of London life, traversing central London daily by foot, alone in the early morning and at night, experiencing its excitements and dangers. Walking and traversing London remained important to him for the rest of his life, and oftentimes seemed almost as necessary to his writing as breathing. All these things, including his private suffering, would later prove of importance in the formation of the great writer he became. For now, the Dickens family wanted to put memories of this painful time firmly behind them:

From that hour until this at which I write, no word of that part of my childhood which I have now gladly brought to a close has passed my lips to any human being. I have no idea how long it lasted; whether for a year, or much more, or less. From that hour until this my father and my mother have been stricken dumb upon it. I have never heard the least allusion to it, however far off and remote, from either of them. I have never, until I now impart it to this paper, in any burst of confidence with any one, my own wife not excepted, raised the curtain I then dropped, thank God.33

Young Dickens may not have been aware of having learned much when he went back to school, but the other boys there seem to have had a sense that he was more mature than they.34 The family was now settled in the poor district of Somers Town, which lay northeast of their usual stamping ground of Marylebone, between the eastern flank of the Prince Regent’s Park and the meandering course of the River Fleet by the ancient church of St Pancras. The small house his parents rented in Johnson Street backed onto open fields south of Camden Town.35 The area is built over now, and it is not at all easy to imagine the semi-rural place it was at the time Dickens was living there between the ages of 13 and 16, when cows grazed in the pastures behind his home. Sadly, not a single building dating from the time of his family’s stay—between 1825 and 1828—survives there.

The district was ruthlessly cut about on both sides by the arrival of the great London railway termini after the 1830s: the Euston line came in first, on the Regent’s Park side, and then the vast swathe of tracks followed to serve the great stations of St Pancras and King’s Cross, to the east of Somers Town. It is very likely that Dickens was thinking of this district when he later wrote about the impact of railway development on existing urban settlements in his essay ‘An Unsettled Neighbourhood’.36

A splendid cartoon by George Cruikshank called London Going out of Town, shows a shower of bricks and phalanxes of animated hods and chimney pots invading the countryside to the north of London, sad hedges being felled, and haystacks gathering up their skirts and running further away.37

Dickens’s generation witnessed and experienced the process Cruikshank satirized. He knew London before the process had really gathered pace and saw it swiftly change: he knew the Marylebone Road when it still had its old tea gardens and statuaries, its ancient inns and cowkeepers; the turnpike on Tottenham Court Road, and Somers Town before the railways. In his lifetime, the age-old farms and fields and footpaths around the northern edge of London were gradually swallowed up in streets, roads, and railways. In the process, areas of that hinterland became scrubby, seedy, and unhappy: north of King’s Cross, for example, Dickens famously described ‘a tract of suburban Sahara’: ‘where tiles and bricks were burnt, bones were boiled, carpets were beat, rubbish was shot, dogs were fought, and dust was heaped’.38

The small house on Johnson Street had something in common with the one on Norfolk Street in so far as each occupied—constituted, even—significant boundaries. While Mr Dodd’s house formed part of the east–west border between Marylebone and St Pancras, the back garden wall at Johnson Street formed part of the northern boundary of the Duke of Bedford’s estate: there is said to have been a boundary stone embedded in the back garden wall to that effect.39 While the Dickens family was living there, this old estate boundary was also the north–south border between London itself, and the next village.

The position of the house gave it wide views over the intervening meadows, but some things rendered it less than bucolic: the St Pancras parish workhouse was within view east across the fields, and the houses were vulnerable to predation by gangs of boys, who came over the back walls.40 There were stories of body-snatchers frequenting the large burial ground around old St Pancras Church. Indeed, while the family had been living away, in another burial ground a couple of fields to the north, an extraordinary event had occurred which doubtless became part of local folklore:

On Saturday se’enight about four o’clock, a party of resurrection men scaled the walls of St Martin’s [in the Fields] burying ground, situated in the fields at the back of Camden Town, for the purpose, as it is supposed, of stealing the body of a grenadier nearly seven feet high, who had died in the poor house of that parish … The sexton, to guard the ground, had, more ingeniously than lawfully, put together a number of gun barrels, so as to form them into a magazine that they might be discharged together. After burying the bodies of the paupers, he made it a practice to direct the muzzle of this formidable engine towards the mound of earth which was the general receptacle for the dead parochial poor. [The following day, he] found spades, shovels, pickaxes, and other resurrection paraphernalia. Among other things he found a man’s hat, through one side of which a bullet had evidently passed [leaving no mark of its exit] and concluded that the bullet had lodged in the head of the owner and killed him, and that he had been carried off by his associates.41

So even though the pastures gave the impression of rural peace during the day, the feeling of vulnerability and marauding criminality at night on this northernmost edge of London cannot have been very welcome. The intervening fields were soon, however, to be engulfed by bricks and mortar: as a local newspaper report had it ‘assisting London in its progress towards York’.42

John Dickens’s debts had been cleared with help from a legacy left by his mother, who had died while her son was in the Marshalsea Prison. Now, Mr Dickens was about to be pensioned off from the Navy, and was developing an alternative career as a freelance journalist, an idea his son would later follow. It was a precarious means of earning a living, but for the next two years, there was evidently sufficient to pay for Dickens to attend the ‘Wellington Classical and Commercial Academy’, a boys’ school just across the pastures of Rhodes’s Farm to the west of Johnson Street, at Mornington Crescent.

When Forster was writing the biography soon after Dickens’s death, he was able to make contact with a number of Dickens’s fellow pupils at the school. These were surviving contemporaries who remembered Dickens as a young teenager. They provide useful corroboration (and modification) of Dickens’s own recollections. One of them had not known that the great novelist was the same boy with whom he had attended school, until he read an essay in Household Words, called ‘Our School’, from which he recognized the fact. He had written to Dickens before his death: ‘I was first impressed with the idea that the writer described scenes and persons with which I was once familiar, and that he must necessarily be the veritable Charles Dickens of “our school,”—the school of Jones!’43

The Wellington Academy was wrongly believed to be a ‘superior’ school, according to these ex-pupils. One of them said: ‘it was most shamefully mismanaged, and the boys made but very little progress. The proprietor, Mr. Jones, was a Welshman; a most ignorant fellow, and a mere tyrant; whose chief employment was to scourge the boys.’44

One cannot help thinking that the loathsome schoolmaster in Nicholas Nickleby probably owes a lot to this ignorant bully. But there was also a much more sympathetic usher, who knew everything and did most of the teaching. Despite general agreement about the intimidating headmaster, all Forster’s correspondents seemed to recollect a lot of mischief and fun. According to Forster, Dickens himself recollected:

linnets, and even canaries were kept by the boys in desks, drawers, hat-boxes, and other strange refuges for birds; but … white mice were the favourite stock, and … the boys trained the mice much better than the master trained the boys. He recalled in particular one white mouse who lived in the cover of a Latin dictionary, ran up ladders, drew Roman chariots, shouldered muskets, turned wheels … who might have achieved greater things but for having had the misfortune to mistake his way in a triumphal procession to the Capitol, when he fell into a deep inkstand and was dyed black and drowned.45

One of Dickens’s fellow students commented that Dickens’s recollections of the school were true to life, but that all the names had been ‘feigned’; we shall discuss this later when looking at an analogous process: the use to which Dickens put local names from Norfolk Street.46 Another fellow pupil judged Dickens’s account to be ‘very mythical in many respects, and more especially in the compliment he pays in it to himself. I do not remember that Dickens distinguished himself in any way, or carried off any prizes.’ The mythic qualities of reality are part of the strength of storytelling, and one cannot know what to believe here. Dickens clearly felt rewarded, but the other observer seems sceptical. The same man denied there had been any Latin teaching at the school, whereas others recollected the Latin master, so his testimony may not be altogether reliable. All these schoolfriends remembered Dickens as the life and soul of everything, a ‘handsome, curly-headed lad, full of animation and animal spirits’. The boys were avid readers, especially of cheap pamphlet fiction, the Penny Magazine and the Saturday Magazine.

They also recalled taking great pleasure in stage plays: ‘We were very strong in theatricals. We mounted small theatres, and got up very gorgeous scenery … Dickens was always a leader at these plays, which were occasionally presented with much solemnity before an audience of boys and in the presence of the ushers.’ Play-acting spilled out onto the street, too, and whereas in the blacking factory period Dickens had feigned affluence to deceive the anxious Bob Fagin, here he felt confident enough to feign poverty for fun. In Drummond Street (near another Charles Street) just north of Euston Square, another friend recalled:

I quite remember Dickens on one occasion heading us in Drummond Street in pretending to be poor boys, and asking the passers-by for charity,—especially old ladies, one of whom told us she ‘had no money for beggar-boys.’ On these adventures, when the old ladies were quite staggered by the impudence of the demand, Dickens would explode with laughter and take to his heels.47

But financial difficulties were actually never far off. In 1827 the family endured the humiliation of an eviction from their small home in Johnson Street, for the non-payment of poor-rates, the local taxes which paid for policing, street-lighting, and the care of the poor. Before stabilizing again, and moving back, the family lodged for a time in ‘The Polygon’, an unusual near-circular block of flats, nearby. The Polygon had literary associations with writers of an earlier generation, such as William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft, and probably carried its seediness well in a district overcrowded with immigrants and refugees.48 Dickens used the place later as the home of Mr Skimpole in Bleak House.

Dickens’s father was now working full time as a freelance journalist, and Dickens himself was submitting small news stories to the press by 1825–6 (when he was 13–14 years of age) for the glorious payment of a penny-a-line.49 ‘Depend on it’, one of his schoolfriends said, ‘he was quite a self-made man, and his wonderful knowledge and command of the English language must have been acquired by long and patient study after leaving his last school.’50

Now adult work was found for Dickens. Great-aunt Charlton knew that his parents were on the lookout for an opening for him. One of her lodgers in Berners Street was a solicitor at Gray’s Inn, Edward Blackmore. He liked the look of Dickens, thought him a bright lad, and took him on as an office junior. In any legal office at this stage Dickens would have been a lowly figure, being still very young and ignorant of the law and its doings, and neither particularly well educated nor well connected. As far as we know, he was not actually apprenticed to either partner at Ellis and Blackmore’s, the fees for which would have been beyond his parents’ reach—his work was clerical in nature, associated with paperwork and keeping the office ticking over: he was not on track to become a lawyer, but to join that large underclass who serviced them, and the courts.

The job of an office junior might be to find or file documents, shift old legal rolls, trunks, and boxes, to slip out on urgent errands, perhaps to purchase legal stationery or supplies, carry confidential messages, briefs, and other documents from office to chambers or to court. He would be at the beck and call of others, might be set to learn accuracy in copying documents, might be asked to serve as a kind of receptionist-cum-gatekeeper in the outer office to defend the chief in his inner sanctum from importunate clients. He would have to learn who was to be ushered in, who excluded, would have to learn the lingo, learn to fib—would have to learn fast. Older clerks, more settled in their ways, might tease or even mock Dickens for being green and tender. He for his part would observe with fine discernment how the world worked, how human stories could be buried in sheaves of paper, indeed how paper could impact on lives: a wise child on the threshold of adult life in London.51

A little cashbook survives from 1828, with entries in Dickens’s 16-year-old handwriting, which shows him by then in a position of trust and responsibility: keeping account of petty cash for the entire office. The small pages record payments to porters for the delivery or receipt of legal documents, payments for repairs and maintenance, and other small amounts for ordinary letters and parcels.

Many of the entries are marked up to be assigned to ongoing cases. There are also entries recording the acquisition of parchment, string, and, yes: red tape.52 Dickens’s clerk’s wages of 15 shillings a week (the same amount as Scrooge paid Bob Cratchit) may have helped make a real difference to the family finances, allowing his parents to contemplate better accommodation. His older sister Fanny was teaching music now, too, so at last both the older children were net contributors to the family’s economy. Early in 1829, when Dickens was just 17, the household left Somers Town and moved back to Norfolk Street.