RETURN TO NORFOLK STREET,

YOUNG PROFESSIONAL, FIRST ESSAYS

DICKENS MIGHT WELL have walked down Cleveland Street since the family arrived back in London. The chances are high that he’d taken that familiar way south from Camden Town or Somers Town: down past the Workhouse and the old family home perhaps to get to Aunt Charlton’s, or possibly, in earlier difficult times he didn’t want to think about, to bring things discreetly to the corner pawnbroker.1 The Dickens family returns to Norfolk Street in this chapter, and we are able to observe the process of development undergone by the young Dickens from his initial employment as a junior legal clerk to his new work as a freelance journalist, which took place during this second period he was living there, above Mr Dodd’s shop once more, between 1829 and 1831. Young Dickens was becoming a young man of the world in London.

Walking south, down Cleveland and Norfolk Streets, and crossing over Charles Street at a diagonal towards Berners Street, Dickens had probably already noticed changes since the family had been living away. Apart from Mr Dodd and a couple of others, almost every shop in Norfolk Street had changed hands in the family’s absence. Twelve years is a long time to a teenager, and in his walks Dickens would have noticed the many small signs of prosperity or its opposite, which had altered in the interval. The leathercutter had gone, and in place of his hides, great rolls of oilcloth were stacked up outside. Mr Dodd’s old competitor next door at No. 9 had disappeared too—replaced by a furniture broker, whose secondhand stock overflowed onto the pavement, blew about on hooks by the door, and festooned his railings. Mr Bridger’s widow at No. 8 was valiantly running the gown-shop alone. Mulloy the solicitor at No. 5 had sold out to a tailor. The Staffordshire chinaware shop was still in Cleveland Street, perhaps with a figurine of the recent murder victim Maria Marten in amongst the dishes and figures in the window, but the sculptors on the corner of Howland Street had gone.2 The area was changing, becoming less interesting, less arty perhaps: tailors, straw hat-makers, wire-workers, and other poorer trades were moving in, and some of the houses seemed rather full. Small indicators, like the state of paintwork or the cleanliness of windows, were slight, but noticeable.

Until the family actually returned to Mr Dodd’s to live, though, the atmosphere inside the house—the smell of the front hall, the way the light fell on the stairs, the dimensions of the rooms, the views from upstairs—were childhood memories, which had probably not yet been overlain. There was probably a strange sensation of déjà vu.

Dickens was almost a man now—in February 1829 he was 17—already out at work and earning his living. To this smart young man these old rooms would have felt smaller, now he was grown. Aunt Mary—who had slept there—was already several years dead, and so much else had happened in the interval.3 His sister Letitia had been born here. When they were last here Mr Dodd’s debts were the problem, not his father’s. The Dickens family had been to the Marshalsea and back since then, and he had survived the blacking factory … and the Wellington Academy. His little sister Harriet had since arrived and departed, and they no longer owned most of the furniture or the precious books that had found their niches in these strangely familiar rooms before.4

But there must have been things—like the handrail on the stairs, the fireplace, the water closet, the corner cupboards, and the dark kitchen below stairs—which remained just as they had been. It was probably a strange return, enough to make Dickens feel curiously old, despite his youth.

And when he gazed down, did the street feel smaller too? Did he notice that the treetops in the Middlesex Hospital garden were taller than they had been when he’d had to climb on a chair to see them? And did he notice what changes twelve years had wrought upon the shops and houses within the purview of the familiar windows? The public houses were still where they had been, and so was the pawnshop, looking much the same. The windows opposite might have looked less so, other than Miss Horsfall’s, who was still there, too, twelve years older.

Mostly the houses probably seemed very much the same, if a little dustier. But a freshly painted shop board on No. 20 over the way announced an arrival on the street: Daniel Weller, a man who dealt in boots and shoes, and cared for them.5 There was a new butcher and a new fishmonger; and another coffee-shop had opened across the street. The choreography of straggling geraniums or herbs on window sills might differ, but the place hadn’t altered that much: the chimneys opposite were still smoking away, and the view was much the same—perhaps a little worse for wear, but still the same old street.

In many ways it was probably good to be back. The place was much closer to the heart of London than was Somers Town or the Polygon, and there was a congenial bustle around Charles Street and Tottenham Court Road, a feeling of variety and liveliness in Norfolk Street, which was probably lacking in the shabbier ladder of streets the family had just left behind. The extended family was closer to hand, which may have been an important consideration.6

Young Dickens could enjoy the news Mr Dodd passed on to his parents, as they picked over what had come to pass in the street during the family’s absence. Old Mr Dugard had died, but his Chancery case endured, and had passed down to Miss Dugard, still at No. 32.7 Old Miser Nollekens in Mortimer Street was dead, too. The theatre in Tottenham Street had changed its name again, and playbills were up in the shop windows, but there were some shady characters living round there now. Tottenham Mews had been completely rebuilt since it was burned down in a fire so fierce that the heat had cracked the Workhouse windows … and speaking of fires, there’d been a terrible one—just down from the Hospital, at the top of Wells Street—nearly the whole block had gone up, a hundred families homeless, everything lost.8

At this stage, Dickens was not yet a writer, so he did not sit down to write a sketch or a passage for a chapter which utilized the experience of returning after long absence to lodge above Mr Dodd’s shop. But later on, in his early Sketches, he did carefully analyse the way shops change over quite long periods of time, and the small indicators which reveal their owners’ (mis)fortunes.9 The experience of Pip in Great Expectations, returning to visit Miss Havisham, has a similar quality, perhaps, to this sense of time passing, and the visible indicators of life-cycles in houses as in persons. Returning to Dullborough town was no doubt a fine description of an adult experience in the Rochester area, but it may well have been informed by the sensations Dickens encountered returning to Norfolk Street in 1829.10

Norfolk Street emerges repeatedly in historical records as a locale in cases of insolvency: there was at least one bankruptcy in each of a dozen of the thirty-four houses in the street between 1815 and 1840.11 But what such records do not tell are the variety of causes of impoverishment, and the efforts made by those on a downward trajectory to put up a good front, and to avoid their fate, especially in a street where a busy workhouse served as a standing rebuke to economic failure. Dickens’s interest in these secret struggles for survival might well have been influenced by lives he witnessed in this street. The consumptive shop girl, for example, in his Sketch on shops, was quite possibly someone whose decline he had observed over time in one of the buildings opposite during the time he was living there.

Dickens’s interest in what passed behind shutters and curtains, his interest in household secrets, is a crucial element in his story-making. It may have been influenced by a tale by one of his favourite authors, whose student protagonist is fascinated by the Devil’s ability to render roofs and walls permeable: to witness whatever he wished to observe.12 But it may also have something to do with his lengthy double exposure—as child and as near-adult—to this well-populated street where several houses opposite were in multiple occupation, and whose rooms and occupants were probably visible to the observant eye … and where a great hospital loomed behind the houses in one direction, and a workhouse and its graveyard in the other.13

Probably the most straightforward description of what Dickens might have seen pass by on the street is his portrayal of the pauper funeral Oliver witnesses, conducted along the streets with no conveyance, at a smart walking pace by Mr Bumble and Mr Sowerberry. Four men from the workhouse served as bearers, carrying the feather-light coffin of a woman who had died of want, and they were followed by her poor husband and old mother, forced to hurry along after, so as not to keep the clergyman waiting. Needless to say, they are forced to wait in the rain (while the parish employees wait in the warm), the churchman being late himself.14 As a child and as an adult, Dickens had probably witnessed many such pauper funerals hurry past his home, bringing the bodies of poor people who could afford no better, from the main parish in Covent Garden to burial in the Workhouse ground. These sorts of funerals proverbially took place in the early part of the day, and were referred to within living memory by Londoners as the ‘nine o’clock trot’.

Unless Dickens had gained access to a building with windows that overlooked the walled graveyard at the back of the Workhouse, however, he had probably not seen what really passed for a funeral in that place. The description of the callous churchman hastily putting on his surplice as he crossed the churchyard, and his perfunctory service, is known to have come from elsewhere.15

As a child Dickens might have shrunk from these sad processions with horror; but as a young man, he probably understood so much more about the humiliation and hurt behind such scenes. The walking rebuke they presented to the society which disregarded them was probably indelibly imprinted in his memory from Norfolk Street.

Exactly when young Dickens gave up working as a legal clerk isn’t known, but at some point at about the period we have now reached, he decided against it as a way of life. He had walked daily to Gray’s Inn for two years now, and perhaps became just as ‘precious warm’ as Mr Lowten, the lawyer’s clerk in Pickwick Papers, who walks to Gray’s Inn from the Polygon. Dickens’s working experience informs his later depictions of Bob Cratchit in A Christmas Carol, and the kindly Wemmick, clerk for the sharp and clever criminal lawyer Jaggers in Great Expectations, both of whom are presented as having reserves of humanity their work does not employ. Both have lives beyond the office—in each case, lives which contribute to the plot, and the charm, of the story.

Dickens had become keenly aware of the pathos of the clerk’s life. The impoverishment he had observed among older clerks presented no hopeful future whatever for himself. Mr Jinks in Pickwick Papers, clerk in a magistrate’s court, is described as a ‘pale, sharp-nosed, half-fed, shabbily-clothed clerk, of middle-age’, who retires ‘within himself—that being the only retirement he had, except the sofa-bedstead in the small parlour which was occupied by his landlady’s family in the day-time’.16 Dickens’s naturalist’s eye examines the niches in the rainforest of London where such organisms thrived, survived, or perished.17 Jinks services the mighty bombast of the magistrate—is constantly at his beck and call—yet outside the court through poverty has the most precarious of domestic arrangements as a lodger in other people’s accommodation. Jinks is not developed as a character, nor is his human predicament explored any further than this brief description, but the sorry sofa bed and his tentative occupancy of it is memorable, nevertheless.

From his later accounts of clerks’ lives it’s clear that being a clerk had been a kind of servitude Dickens found thoroughly irksome. The subordinate status and the sheer boredom of being an employee of low status, the under-use of his capacities and undervaluation of his abilities appear to have given Dickens the determination to improve himself as a means of escape. One possible route his ideas took was to consider entering the law himself, but although he held on to the possibility for several years, mercifully, Dickens found other ways of making his living: it would not have suited him.

Dickens’s lawyers, in Pickwick and elsewhere, suggest that he came to regard much of the legal system as a conspiracy: efficiently extracting as much cash as possible from anyone unfortunate enough to fall into their hands. Clerks are shown aping their masters in superciliousness and contempt, especially towards clients impoverished by the law itself. In this, Dickens joined an existing tradition: another novelist ascribed a particularly hellish demon to assist the work of attorneys, bailiffs, pleaders, counsel, and judges, while Fleet Street caricaturists pictured a conversation (observed by a lawyer’s clerk, concealing his laughter behind his hand) between a naïve country Farmer and his predatory well-dressed lawyer:

Farmer: ‘When do you think the Cause will be finished, you know I’ve sold my farm and I really am reduced to my last guinea, which makes me very unhappy.’

Attorney: ‘Why, if that’s the case I really believe it’s very near finished. But you ought to be very happy when you consider I have reduced your opponent to the last farthing.’18

The pity of these kinds of goings-on is dealt with in Pickwick mostly in a light and comedic fashion, but the truth of what Dickens had observed nevertheless shows through: a promising case concerns not its justice, but its potential for fees. Decent lawyers appear in the novels too, but the young Dickens generally presents his legal professionals and the system they stand for as altogether without principle.

After Ellis and Blackmore Dickens tried a brief spell as a clerk to an attorney, but he eventually found the law insupportable as a prospective career choice for himself. Fortunately there were other routes out of clerkship, and exposure to the legal labyrinth of London for a couple of years had been valuable in helping Dickens perceive that his future rightly lay elsewhere. It had been extremely useful to him. Like the blacking factory and the Wellington Academy, his exposure to the legal life of London provided him plenty of material.19

Dickens’s father had learned shorthand, and was supporting the family as a freelance newspaperman. He seems to have acquired knowledge of the skill and the business of journalism from his own brother-in-law, Mrs Dickens’s brother John Barrow, who in 1828 had established the best parliamentary reporting journal of the day, The Mirror of Parliament. Despite the insecurity of journalism, its variety and interest—and especially the freedom of the working life his uncle and his father were carving out for themselves—appealed to young Dickens. It was not long before the disaffected young clerk determined to learn shorthand himself. He had kept his day job for the time being, studying in whatever spare time he could find. Long afterwards, when he came to write David Copperfield (whose hero undertakes a similar course of self-education), Dickens described with some humour the difficulties involved in mastering this skill:

I bought an approved scheme of the noble art and mystery of stenography (which cost me ten and sixpence); and plunged into a sea of perplexity that brought me, in a few weeks, to the confines of distraction. The changes that were rung upon dots, which in such a position meant such a thing, and in such another position something else, entirely different; the wonderful vagaries that were played by circles; the unaccountable consequences that resulted from marks like flies’ legs; the tremendous effects of a curve in a wrong place; not only troubled my waking hours, but reappeared before me in my sleep.20

The technique involved learning to think phonetically, and the signs for every sound or combination of sounds. Transcribing speech into the sign language of shorthand was a matter of getting ‘up to speed’, so that an accurate record might be kept at the normal speed of speech. He had then to be able to complete the procedure by deciphering correctly what had been transcribed. Much of this effort was probably done at home in Norfolk Street, using his siblings to dictate to him.

Copperfield makes wry fun out of the difficulty of the entire process, but in fact, young Dickens seems to have applied himself so well to the task that it wasn’t long before he decided to try earning a living by it, and within a comparatively short time, he had so mastered it as to become recognized as pre-eminent, even by other reporters. It was while he was living above Mr Dodd’s shop in Norfolk Street that Dickens passed his seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth birthdays, and first entered the Reporters’ Gallery in the Houses of Parliament. His life was changed from this address.

Father and son belonged to an era which greeted with interest and satisfaction the publication in 1830 of an anonymous work entitled The Pursuit of Knowledge Under Difficulties, which featured nearly a hundred short biographies of men lacking social advantages or university education who had nevertheless made a success of their lives: figures such as Shakespeare, Benjamin Franklin, Benjamin West, and Richard Arkwright.21 The book exemplified the value of self-discipline and self-education, and asserted the dignity and importance of the class of men below the gentry and aristocracy, always the objects of social snobbery.22 The book was a runaway bestseller, since it answered the longing of many an under-educated person for recognition of their merit, in spite of their social predicament, and served as an inspirational self-help guide to ways out of the trap which—despite industrialization—feudal society continued to impose.

FIGURE 26. Thomas Gurney’s Brachygraphy: the edition that Dickens bought to teach himself shorthand. Title page and shorthand versions of the opening verses of Genesis, and the Lord’s Prayer. Published in London by Butterworth, 1825.

FIGURE 27. Young Dickens, c.1830. Stipple engraving from a miniature painted by Dickens’s aunt, Janet Barrow, at about the time the 18-year-old Dickens was living in Norfolk Street. She was living in Marylebone at the time. The engraver is unknown.

In a society that was rife with social snobbery, and socially still quite rigid and closed to the working classes and those below them, the book stood for a movement which was coming of age just as Dickens was coming of age himself, to expand the notion of social worth and human potential. Dickens was later a passionate campaigner for wider educational facilities, public libraries, educational institutes, and ragged schools. In 1843 he addressed the inaugural meeting of the Manchester Athenaeum, alongside Benjamin Disraeli, on the contrast between the ‘path jagged of flints and stones’ laid down by brutal ignorance for the homeless to walk upon, and the boon of literacy by which one could join in company:

watching the stars with Ferguson the shepherd’s boy, walking the streets with Crabbe, a poor barber here in Lancashire with Arkwright, a tallow-chandler’s son with Franklin, shoemaking with Bloomfield in his garret, following the plough with Burns, and, high above the noise of loom and hammer, whispering courage in the ears of workers I could this day name in Sheffield and in Manchester.23

The time spent in study, perfecting his shorthand and getting up speed, had helped propel the transformation of the factory boy into a young writer. Within a decade of starting out as a junior clerk, Dickens was the well-known author of Sketches by Boz, Pickwick, and Oliver Twist.

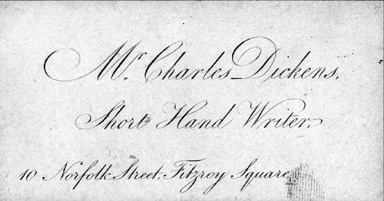

A remarkable object dating from this era of Dickens’s life is his calling card. Only one example is as yet known to be in existence. It carries the legend ‘Mr Charles Dickens, Short Hand Writer, 10 Norfolk Street, Fitzroy Square’.24

The calling card is neat, diminutive, and elegant: so fragile and ephemeral that its importance might be easy to overlook. But, like the old workhouse, and Mr Dodd’s house on the corner, it is a most extraordinary survival. Having a calling card was part of the process of becoming a professional, just as it is today. This card may have brought Dickens work, or contacts that brought him work. It was almost a travelling part of himself: a statement of professional status, an object which served to solicit employment, and which has travelled through time to us. Where might Dickens have been when he reached into his pocket-book to take it out, and hand it over … and to whom? Research may yet reveal the story of its survival, but for now it is enough for us to recognize that it constitutes a vital piece of incontrovertible evidence that young Mr Dickens lived in Norfolk Street, and of his adulthood at the time.

FIGURE 28. Charles Dickens’s calling card, demonstrating his professional status while he was living in Norfolk Street for the second time, c.1830.

The card is important because it gives us a clear view of how Dickens wanted to present himself to others as he began to operate as a professional shorthand writer. This is really helpful, because the Norfolk Street years (1829–31) come at the end of a period of his life difficult to chart in any detail. Only three letters survive for the entire period up to 1831, none of them from this address. The lettering on the card is calligraphic rather than typographic in inspiration, resembling the personal quality of handwriting rather than the impersonality of type. Its modest flourishes suggest and demonstrate Dickens’s love of elegance, a sort of controlled flamboyance: slightly flowery, but perfectly legible. The lettering leans forward, optimistically, as if it has great expectations! The ‘Mr.’ gives this young man a grown-up feel, while the ‘Fitzroy Square’ appended to the Norfolk Street address, would have looked socially good to anyone who did not know the area too well.25 To us, it reveals his social aspirations. The central statement, ‘Short Hand Writer’, shows his pride in his own accomplishment. The card demonstrates Dickens’s self-respect: his recognition of his own achievement, his trust in his own competence, in the value of his own mental and manual labour, and his satisfaction in the financial rewards of independence.

Dickens would not have spent precious earnings to pay to have something as important as this printed had he believed it would become obsolete quickly, so the card shows, too, that at the time he had it printed—which is likely to have been in 1829 or 1830—Dickens felt Norfolk Street was a secure address from which to advertise his talents: it was home.

The chronology of the key decade in Dickens’s life between the ages of 15 and 25 (shown in Table 5, page 312) demonstrates that his determination to acquire and perfect his shorthand skills materially changed his life and prospects. Dickens’s decision to extricate himself from the world of the legal clerk set the course for the possibility of his later writing.26

A number of his biographers ascribe the impetus for self-improvement to Dickens’s meeting with Maria Beadnell in May 1830 and their subsequent futile courtship, but the chronology demonstrates it pre-dated that. The pivotal era appears to anticipate the key change from clerk to reporter, employee to freelance, between Somers Town and Norfolk Street. In relating David Copperfield’s passion for the vacuous Dora, Dickens presents his efforts as biographers have generally accepted, but in real life Dickens applied for his ticket at the Reading Room of the British Museum before he met Miss Beadnell. Aspiring to marry was doubtless an effective stimulus when he flagged, but it was a product rather than the cause of his determination to improve himself.

Dickens seems to have made the transition from clerk to independent professional shorthand writer around the time of the family’s move to Norfolk Street, and he applied for his Reader’s ticket at the British Museum from there too. The alacrity with which he applied for his ticket suggests that he had been waiting some time for that day to arrive. The entry in the great ledger still preserved in the Museum for 8 February 1830, the day after his eighteenth birthday, reads:

Dickens (Chas.) 10 Norfolk Street Fitzroy Square. C.W. Charlton 16 Berner St W. Ward 48 Berner St.27

The two names which follow Dickens’s address here are those of the sureties or referees all new Readers were required to furnish: in his case Uncle Charlton, and a neighbour of his in Berners Street, William Tilleard Ward, a doctor who specialized in human deformity, especially of the spine.28 Dickens renewed his ticket nine months later in October 1830, and again after a further nine months had elapsed in May 1831, in each instance from Norfolk Street. John Dickens followed his son into the Reading Room in the midsummer of 1832, attending along with George Hogarth, his son’s future father-in-law, and a friend from Lincoln’s Inn, James Bacon, who later served as approving Counsel to Dickens’s contract with Chapman & Hall for Nicholas Nickleby.29 John Dickens’s referees were Henry Bacon of the Temple, and his own brother-in-law, John Barrow.30

The kind of journalism in which Dickens and his father were apparently occupied at that time generally appeared anonymously or pseudonymously—either without bylines, or with (often false) initials—and hence almost impossible to find, or attribute. Young Dickens seems to have gone about with his father at the outset, visiting public legal venues, such as police courts and inquests, to pick up stories. Jobbing newspaper hacks were paid a penny or a penny-half-penny a line, but it was the skill of finding lines that newspapers would pay for which was the key to success: looking for hot news or unusual stories, finding the angle of interest in mundane stories, writing persuasively, getting material written in advance of other journalists, finding niches to supply within the print industry of Fleet Street, or elsewhere.31 It may be that for a time, neither of them felt sufficiently confident to follow verbatim stories alone, that they were taking shifts with each other, and assembling stories together later.

It was helpful to both of them that Uncle John Barrow had ploughed his own furrow ahead of them in the world of the press: he had worked as a shorthand writer at Doctors’ Commons, an ecclesiastical court dealing with matrimonial law and wills, and had then made his name as a shorthand journalist covering the scandalous divorce trial of Queen Caroline and King George IV for The Times, in 1820. Barrow was also a good source of information: he understood relationships within Fleet Street, could help with introductions (i.e. networking), and (as we have already seen for John Dickens at the British Museum) he could and did provide character references. He later employed Charles Dickens on his own journal, The Mirror of Parliament.

It was a definite advantage to a journalist to be able to tap into a field of expertise. It is known, for example, that in 1826 Dickens’s father, under the initial letter ‘Z’, published a series of nine articles on marine insurance in a newspaper called The British Press, in which he recommended the probity of Lloyd’s of London. These articles presumably utilized existing knowledge from his naval employment. The underwriters at Lloyd’s allowed John Dickens a grant of 10 guineas for the articles, after he appealed to their good offices when the newspaper for which he had written them failed, owing him payment. The exchange of letters detailing this interchange, and the bad luck behind it, was only discovered in the 1950s, and helps us appreciate that not all of John Dickens’s financial difficulties were self-generated. Freelance journalism is an unreliable business.32

It was natural too that Dickens should develop an interest in law reporting. This kind of work was a treadmill, no doubt, like all daily work, but much depended on the energies and initiative of the individual, and that doubtless made it much more congenial to Dickens than being a clerk. John Britton, later a literary supporter of Dickens, referred to his own years as a junior in a solicitor’s office as a kind of ‘slavery’.33 But as a freelance, unless Dickens churned out material, he had no pay. In order to sell work, both Dickens and his father would have had to cultivate a style of reporting as close to existing newspapers’ styles as possible, so it is likely that most of their material will never be identified.34

In 1830, while he was living in Norfolk Street, Dickens followed his uncle, and began work at Doctors’ Commons, where Uncle Charlton worked as a clerk.35 Dickens worked from the Reporters’ Box as a freelance shorthand writer for the proctors there, recording cases verbatim when required. He said afterwards that ‘it wasn’t a very good living (though not a very bad one), and was wearily uncertain’. Dickens had desk space in adjacent Bell Yard, for quiet work transcribing and writing. His income at the time was both low and irregular. This is the period of his life in which the Dickens scholar John Drew suspects Dickens might have been composing verses for advertising shoe-blacking, for the princely sum of three shillings and sixpence each set of verses.36

Doctors’ Commons was situated in a warren of streets between St Paul’s Cathedral and the River, within easy reach of the Old Bailey and the lesser courts Dickens already knew from his clerking days. It was also conveniently placed for the newspaper world of Fleet Street, and the many small publishers around the western fringes of the City, in Paternoster Row and Cheapside. Among these was an enterprising printer-publisher, Jack Fairburn, whose songbooks, jest-books, cheap gothic novels, ‘crim-con’ divorces and horrid murder case reports, news chapbooks, and twelfth-night entertainments were displayed in his shop window on Ludgate Broadway, ‘OPPOSITE THE OLD BAILEY’, a lane or two towards Fleet Street from Bell Yard.37

In among the unique Dexter Collection of rare Dickens materials held in the British Library is a sixpenny chapbook published by Fairburn, entitled Burking the Italian Boy: Fairburn’s Edition of the Trial of John Bishop, Thomas Williams, and James May for the Wilful Murder of the Italian Boy. It is inscribed on its outer wrapper with a handwritten note from Dexter himself:

F.W. Pailthorpe gave me this pamphlet

stating that it was ‘reported’ by

Charles Dickens & that he had

this information from an authoritative

source. The description of the prisoners

(pp: 21–22) bears evidence of C.D’s hand.

John F Dexter.

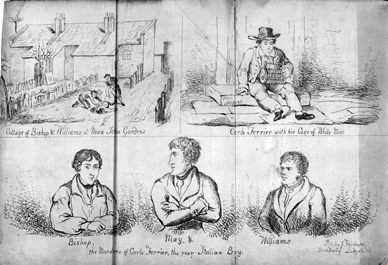

This little chapbook may be among the earliest things Dickens wrote, and as we shall see, the Italian Boy had a sad connection to Norfolk Street. Pailthorpe was a late Victorian illustrator of Dickens who had known George Cruikshank in his later years. Cruikshank and his father and brother, and possibly his nephew, had all worked for Jack Fairburn.38 This chapbook looks to have been a hasty production, designed to cash in on the great wave of fear known as ‘burkophobia’, which gripped the metropolis late in 1831, when it was discovered that the crimes of Burke and Hare had been replicated in London. In Edinburgh in 1828, Burke and Hare had murdered sixteen people, mostly lone street folk seeking shelter.39 The motive for that ghastly series of killings had been the money raised from the anatomist Dr Knox, who had purchased the corpses for dissection, and who had asked no questions as to how they had been obtained.40

FIGURE 29. The murderers of the poor Italian Boy. Fold-out frontispiece from The Italian Boy chapbook, published by Jack Fairburn, London 1831. The images show signs of haste and are the work of more than one hand.

When the new discovery was made in November 1831, ‘burkophobia’ broke out afresh, now with a metropolitan focus. The poor were so fearful that even regular burglars were shopped as possible body-snatchers.41 Three men, seasoned body-snatchers, had delivered the sacked-up body of a young teenager to the new Medical School at King’s College Hospital, at the City end of the Strand. Suspicious about the cause of death—the anatomist had asked them to come back later for their money, pretending he had only a large bank-note—the police were waiting.42

It turned out that the victim was an Italian boy, Carlo Ferrari, who had made his living on London’s streets showing a little revolving cage of performing white mice. He’d been seen begging outside a public house near Nova Scotia Gardens, Bethnal Green on the dark afternoon of 3 November, and there had fallen prey to two of the most despicable ruffians in London, Bishop and Williams, who plied him with drink (perhaps laced with opium) and, under cover of darkness, drowned him in a well in their garden. It was a cunning means of murder, which left no obvious marks. The men had already sold corpses, which despite their freshness had not raised suspicion. The major problem with burking was the destruction of evidence in the dissecting room, but fortunately in this case that was circumvented by the anatomist’s quick thinking. The third brute, May, had helped transport the corpse, and extracted the boy’s teeth after death for sale to a dentist, but had apparently not been party to this murder.

Whether Dickens wrote the report on the trial of the ‘London Burkers’ for Fairburn will probably never be known for certain. But it seems to be possible, both because of Pailthorpe’s statement to Dexter, which is likely to have been reliable, and because of the date of the events, which fell in a parliamentary recess, when Dickens would have been short of regular work. A number of other threads connect Dickens to the story, and perhaps link the Cruikshank family of artists to its illustrated frontispiece.43

If Pailthorpe’s informant was Cruikshank himself, it may be that the chapbook is the earliest item on which his family and Dickens worked together, unwittingly and without collaboration.44 Near the end of Oliver Twist, when Fagin is in the dock at the Old Bailey, Dickens has him fix his attention for a few moments on a young artist sketching his likeness from the public gallery, perhaps nodding to Cruikshankian efforts at documentary recording for Jack Fairburn in that very courtroom. If this idea is correct, this reference complements the manner in which Cruikshank had pictured likenesses of Dickens himself in the illustrations to Sketches by Boz, before the real identity of ‘Boz’ had become publicly known. By picturing an anonymous artist in the gallery at the Old Bailey during Fagin’s trial, Dickens may have been making a reciprocating nod towards the relationship and identities of the author and the illustrator within Oliver Twist.45

The collector J. F. Dexter evidently had a distinct sense that Dickens’s voice could be heard in parts of prose in Fairburn’s chapbook, which appears to me justified. It says ‘TAKEN IN SHORT HAND’ on the title page, with the words given separately, just as they appear on Dickens’s calling card.46 The manner in which the testimony is reported and edited is simple and clear, the case is presented to the reader in a thoroughly competent, straightforward way. This partly reflects the skill with which the prosecution lawyers built their case, but the chapbook’s summaries are both pertinent and succinct, the whole production well crafted in a journalistic sense, too.

One of those giving evidence in the case was a member of the ‘New Police’ (recently instituted by Robert Peel), who sounds like a seasoned detective: his evidence is given to the reader without flinch. Another witness, a boy of only six and a half, was first examined as to the nature of an oath. The report reads: ‘The child, with infantile simplicity, said that he knew it to be a very bad thing to tell a lie; that it was a great sin; and that he who would swear falsely would go to h--l, to be burnt with brimstone and sulphur.’

FIGURE 30. Early coaches, an original Cruikshank etching from Sketches by Boz, showing Charles Dickens (in the top hat by the counter) incognito, in 1836.

It’s the space and weight given in the report to the process of clarifying the boy’s views, the language of the boy’s statement, and the sentiment in that ‘infantile simplicity’ which feel to me like Dickens. This moment seems also to find an ironic late echo twenty years afterwards in Bleak House, when Jo the crossing sweeper expresses uncertainty about the afterlife in the Coroners’ court: ‘Can’t exactly say what’ll be done to him arter he’s dead if he tells a lie to the gentlemen here’—and is dismissed from the stand.47

There are other moments, sometimes turns of phrase, spellings, and sentence constructions we know Dickens used, the confident use of ‘we’ meaning oneself; and moreover a sense of both analysis and power in the writing, which even at this early stage in his writing career (the chapbook appeared two years before the first of his Sketches was published) could indeed be his voice. There is a single snatch of quoted dialogue so telling that it could not be improved upon. One of the guilty men is reported as having said to the other: ‘It was the blood that sold us.’

It is difficult to draw any stylistic conclusions from the edited transcription of other people’s words taken down in shorthand. But while the Jury was out, the process of verbatim reporting was suspended, and the Fairburn correspondent described the tense atmosphere in the court in his own voice. The change of voice is signified in the chapbook in a different typeface. Some extracts are given here, so the reader can catch their flavour:

The interval … was a period of intense anxiety to every one in court; and, as is usual on such occasions, there were various conjectures hazarded as to what would be the verdict as to all the prisoners. That a verdict of ‘Guilty’ would be returned against two of the prisoners, namely Bishop and Williams, none who heard the evidence, and the summing up of the learned Judge, could entertain any rational doubt … [concerning the third defendant, May] the general opinion, as far as we could judge from what was passing around us, was—that the circumstantial proof not being in his case so strong as it was in the case of his fellow-prisoners, the Jury would acquit him; but still there were many who thought the proof of a participation in the murder clear and perfect as to all the parties.

The most deathlike silence now prevailed throughout the court, interrupted only by a slight buz in the reintroduction of the prisoners.

Bishop advanced to the bar with a heavy step, and with rather a slight bend of the body; his arms hung closely down, and it seemed a kind of relief to him, when he took his place, to rest his hand on the board before him. His appearance, when he got in front, was that of a man who had been for some time labouring under the most intense mental agony, which had brought on a kind of lethargic stupor. His eye was sunk and glassy; his nose drawn and pinched; the jaw fallen, and of course the mouth open; but occasionally the mouth closed, the lips became compressed, and the shoulders and chest raised, as if he was struggling to repress some violent emotion. After a few efforts of this kind, he became apparently calm, and frequently glanced his eye towards the Bench and the Jury box; but this was done without once raising his head. His face had that pallid blueish appearance which so often accompanies and betokens great mental suffering.

Williams came forward with a short, quick step; and his whole manner was, we should say, the reverse of that of his companion in guilt. His face had undergone very little change; but in the eye and in his manner there was a feverish anxiety which we did not observe during the trial. When he came in front, and laid his hand on the bar, the rapid movement of his fingers on the board—the frequent shifting of the hand, sometimes letting it hang down for an instant by his side, then replacing it on the board, and then resting his side against the front of the dock, shewed the perturbed state of his feelings. Once or twice he gave a glance round the Bench and the Bar, but after that he seldom took his eye from the Jury box.

The spellings of ‘buz’ and ‘shewed’ are typical of Dickens, and the insightful attention to posture, gesture, facial expression, and movements of the singular eye as a means of accessing/conveying mental state are all suggestive of his early style. The closest parallel however, is the ‘deathlike’ silence, which is a description Dickens actually uses in Oliver Twist for the hiatus in court at the exact same moment the verdict is about to be given in Fagin’s trial:

As he saw all this in one bewildered glance, the death-like stillness came again, and looking back, he saw that the jurymen had turned towards the judge.48

Interestingly, when extracts from the Fairburn chapbook were tried in the text search facility of the British Library’s online newspaper collection, it emerged that several passages closely resemble coverage of the trial in the weekly newspaper The York Herald, which appeared a week after the trial. Internal evidence suggests that Fairburn’s chapbook was probably written and rushed into print straight after the death sentences were handed down at the end of the trial on Friday, 2 December 1831, so as to be ready for sale to the crowds attending the execution at Newgate on the following Monday morning. The pamphlet mentions that the criminals had been sentenced the previous day, but does not cover the double execution, whereas the York newspaper report appeared the following Saturday, and covers the entire trial and execution. Further research will be required to discover if anything more can be found to clarify the source of the report: if Dickens had associations with York at that time, if he (and/or his father) might have done other work for the York Herald as freelance London correspondents, or if the paper simply noticed the quality of the text in Fairburn’s chapbook, and pirated it.49

Dickens knew and loved Fairburn’s output of comic songs, toasts (‘May the wing of friendship never moult a feather’) and glees, from little books which he may have seen and acquired from Mr Dodd’s shop.50 Among Fairburn’s chapbook output are others which Dickens could well have known, such as the dramatic report of the wrecking of a pleasure steamer on the coast of North Wales, with terrible loss of life. Fairburn’s Narrative of the Total Loss of the Rothesay Castle Steam Vessel on 17 August 1831 has a colour fold-out frontispiece showing a spectacular aerial view of the great deck of the ship dramatically tilted towards the viewer, with individuals discernible in the water or in desperate positions on the deck, awash, about to be shot into the waves, with a storm at its height, and all in tragic sight of land.51 The chapbook sold for sixpence. Reading the text, I wondered if John Dickens might perhaps have had a hand in it, as it seems to be an informative and dextrous compilation of reports he might have been able to access at Lloyd’s and elsewhere, with parliamentary material, perhaps obtained via the Mirror of Parliament. The ‘melancholy catalogue of mortality’ listing those known to be lost, and the detailed descriptions of the still unidentified drowned bodies, including those of young children, with carefully catalogued identifiers like height, hair colour, and details of initials on linen, and calling cards, for each body washed ashore on the Welsh coast, makes for very poignant reading. In later life in David Copperfield Charles Dickens wrote a dramatic description of a shipwreck (in which Steerforth is drowned), and many years afterwards, he made a special journey to the desolate rocky coast of Anglesey, after the wrecking of the Royal Charter steamship in the great hurricane of 1859. The journey resulted in one of his finest essays, ‘Shipwreck’.52 The latter, in particular, is so very similar to this early chapbook in content, that it prompts thoughts about some of Fairburn’s output, and its influence upon—or creation by—John Dickens and son.

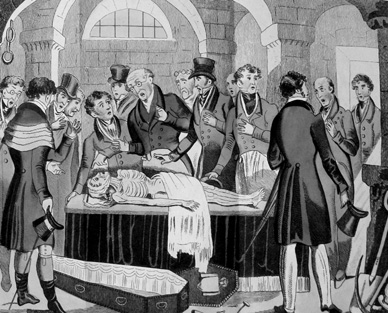

Fairburn’s ‘Extreme Cruelty to Children, MURDER!’ reported the details of an inquest on the bodies of two young girls, who had been apprenticed out ‘on-liking’ from two London workhouses, St Martin’s and Cripplegate, and who had been starved and maltreated to death in 1829 by their employer, Esther Hibner, in a domestic manufactory close to Somers Town.53 In this instance, I would not suggest Dickens reported on the case, but it was widely reported and is likely to have been familiar to him, since the manner in which Oliver is so starved as to be grateful for animal scraps to eat at Sowerberry’s perhaps recalls details from the trial. Hibner’s trial revived popular memories of a much older case, that of Elizabeth Brownrigg, hanged for a similar murder in the 1760s.54 Brownrigg was infamous as an archetype of female cruelty from chapbooks and ballads, and her fate at the gallows awaited the guilty employer in this case, in 1829.55 Jack Fairburn’s chapbook has a dramatic fold-out frontispiece, showing the entire Coroner’s jury viewing with horror the emaciated body of one of the girls who died from the maltreatment, Margaret Howse, or Hawse.56

FIGURE 31. The Coroner’s Jury. The extraordinary frontispiece to ‘Extreme Cruelty’ published by Jack Fairburn, London, 1829, reporting the dreadful facts of the Esther Hibner case. Artists unknown.

The chapbook catalogues a sequence of vicious maltreatment by the girls’ employers, and fatal neglect on the part of the parish authorities. As in the case of the factory boy Robert Blincoe from St Pancras Workhouse, whose appalling experiences have already been mentioned above, there was no real oversight of the fate of these children once they were apprenticed out. At their worst, workhouse apprenticeships like these can be seen to have been almost an official form of child trafficking. The brutish treatment meted out to these girls, and the desperate fear among the other friendless apprentices at the factory, who were cowed into silence by the sadistic brutality they had witnessed being inflicted, is the real-life background to the collusion in Oliver Twist of the workhouse management personified by the man in the white waistcoat, and the sadistic employer—Gamfield, the donkey-beating master sweep—on the doorstep of the workhouse. Although Dickens is often accused of melodrama, he is seldom described as a master of understatement. Yet his use of Gamfield’s treatment of the donkey as an analogue for institutional inhumanity towards the child, is masterly.57

Deaths like those of Francis Colpitts and Margaret Howse, and especially the murder of the Italian Boy, revealed a murderous level of predation upon poor children in London, which had probably not been contemplated before. Dickens’s friend Leigh Hunt was still thinking about it several years later, when he published this passage in the London Journal in 1834:

I had only just heard of the murder of the poor wanderer, Carlo Ferrari, and having walked out in the hope of removing from my mind the painful feeling such an atrocity awakened, I happened to overtake a lad with an organ and a little box of white mice. I now found any attempt to forget the murder fruitless, and now minutely observed the youth before me. [He sees he is Italian and follows] … he stopped opposite to a print shop, and having scanned the contents of the window, he suddenly fixed his attention on a drawing: a gleam of pleasure lightened up his face [the boy had seen a picture of the Madonna and Child] ‘And they have murdered thy countryman,’ thought I, ‘and he was a stranger’.58

There is good reason to believe that the Italian Boy’s case held especial resonance for Dickens. A cluster of curious affinities suggests why this might have been so. His possible authorship (or co-authorship with his father?) of the Fairburn chapbook is one. Another is that the Italian Boy’s body was buried in the pauper burial ground right behind the Cleveland Street Workhouse. Like so many other poor people from the parish of St Paul, his coffin had been borne out of central London and carried past the front door of 10 Norfolk Street.

Later, from the rear windows of the Workhouse the pauper inmates might have witnessed the sorry process of exhumation, when the boy’s body was judicially dug up again for a fresh official identification, and buried a second time. The woman who identified the Italian Boy’s body in the burial ground behind the Workhouse had last seen him alive in Oxford Street, and another witness had seen Bishop’s children playing with white mice in a revolving cage. Both Oxford Street and white mice would have had echoes for Dickens—the latter with those hidden in his own desk at the Wellington Academy.59

In 1836, nearly five years after the Italian Boy’s case, Dickens visited Newgate Prison for a Sketch he was writing, a visit which doubtless also influenced his conception of the end of Oliver Twist. The first criminals he mentions having encountered there were Bishop and Williams:

Following our conductor by a door opposite to that at which we had entered, we arrived at a small room, without any other furniture than a little desk, with a book for visitors’ autographs: and a shelf on which were a few boxes for papers, and casts of the heads and faces of the two notorious murderers, Bishop and Williams—the former, in particular, exhibiting a style of head, and set of features which would have afforded sufficient moral grounds for his instant execution at any time, even had there been no other evidence against him.

The Parish of St Paul Covent Garden had been the prosecutor in the murder case at the Old Bailey, because before his death the Italian Boy had been living in that parish: his lodgings had been in a well-known rookery in Charles Street, near Covent Garden: a dead-end at the southern end of Bow Street. Later, in the mid-1830s, this slum was cleared and a new street was cut through southwards to the Strand and Waterloo Bridge. The new thoroughfare was called Wellington Street North, and Dickens later occupied two premises there: first for the offices of Household Words, and another for All the Year Round. The latter occupied a corner, overlooking the site of the old slum.60

It’s clear from the ‘autobiographical fragment’ that as a child in the blacking factory Dickens had felt abandoned, and that his later observations on that period of his life reflect his subsequent memories of his feelings as a boy. Objectively, while his parents were in the Marshalsea he was indeed an abandoned child. But the Italian Boy’s case (and most likely others to which Dickens was exposed in the press of the day, and in the courts he attended as a reporter) compounded these early memories with an overlay of adult knowledge of what might have happened to him, had he been less lucky. Garments from people other than the Italian Boy were found buried at Nova Scotia Gardens. Before their execution, Bishop and Williams are rumoured to have confessed to sixty murders, not just the one for which they were finally caught.61

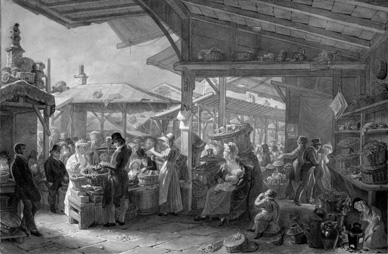

FIGURE 32. Covent Garden Market. A lovely watercolour by George Scharf, 1825. It shows the busy market as Dickens would have known it when he was a child worker in the nearby blacking factory, only the previous year. He often wandered through the market alone, experiencing the profusion and liveliness of the place. There would have been other times, too, when it was silent and empty of stalls, a wide open space. The pent roof and clock tower of Inigo Jones’s great Church of St Paul Covent Garden rears above the stalls on the right. The Italian Boy’s lodgings had been close by.

It is known that in the 1840s Dickens visited a charitable school for Italian boys established in Clerkenwell on more than one occasion. ‘I was among the Italian Boys from 12 to 2 this morning,’ Forster quotes him writing in a letter.62 It would appear that Dickens had taken the original Italian Boy’s predicament very much to heart.

Dickens once commented to Forster on chance and mischance in altering lives, when he told him about an opportunity he had missed, through illness, to audition as an actor at Covent Garden Theatre: ‘See how near I may have been, to another sort of life.’ The sentiment could surely have applied to the Italian Boy; and to a different sort of death.63