ST PAUL’S PARISH, FARMING THE INFANT

POOR, PAUL PRY, PARLIAMENT

THE SAME YEARS were important for the Workhouse, too. In several parishes with which Dickens was familiar—St Paul Covent Garden, St Giles and St George Bloomsbury, and in St Marylebone—there were active moves afoot to bring greater democratic oversight to the management of the local government.

Parish ‘Select Vestries’ were unelected, self-perpetuating parish management committees, and were widely regarded as corrupt. St Martin’s in the Fields (which surrounded Covent Garden parish) was a particular focus of parishioner disaffection.1 Reform was ‘in the air’, and the political agitation of the day was in many places focused as much towards unrepresentative local government as it was towards the unrepresentative national Parliament.2 To give an idea of the nature of the local democratic deficit, the population of the parish of St Paul Covent Garden was over 5,000, while the number of property owners who had a right to vote for parish representatives was only 73.3

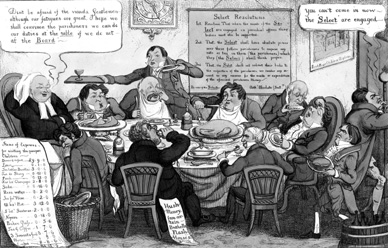

There had been rumours buzzing around the parish of St Paul Covent Garden for some time, when on April Fools’ Day 1828 rumours became allegations: of gross feasting on the part of the Select Vestry, and of corruption involving hush-money from brothel owners. Printed caricatures showing the gentlemen of the Select Vestry feasting at public expense were put up on display in print-shop windows in Piccadilly and elsewhere, spreading the story far and wide, well beyond the parish. Displayed legibly on the caricature was an itemized hospitality bill: dinners at 9 guineas a head, prodigious amounts of alcohol, champagne, rose-water, et cetera, and the added costs of coaches, and broken glasses. The faces of the diners were portrayed so well as to render them individually identifiable.4

FIGURE 33. Select Vestry Comforts, showing the gluttony of the Select Vestry of the parish of St Paul Covent Garden. Added manuscript annotations in the border suggest that the artist’s likenesses closely identified several of those involved. Etched by Thomas Jones, published by Fores of Piccadilly, 1828.

The Parish Beadle was shown wielding his staff of office to keep intruders out while the ‘Select’ were ‘busy’, and a wall-notice announced their power to impose any poor-rate they chose. The gluttony is depicted as having followed upon an inspection of the parish’s Infant Poor Establishment, the austere exterior of which features in a painting on the wall in the same caricature.

Since 1767 a special Act of Parliament known as Hanway’s Act, designed to prevent devastating levels of infant mortality among parish children in the metropolis, required every London parish to establish a ‘branch’ workhouse in the countryside at least three miles outside London, in which to rear their infant poor.5 Parish children were sent out to these places—also known as ‘baby farms’—after weaning, and reared until they were old enough to return to the workhouse in town, from which they would be assigned to employers. Periodic ‘inspections’ of these baby farms were part of parish management of the metropolitan poor. Dickens mentions that Mr Bumble was always sent a day ahead to warn of a likely inspection, and that the children always looked ‘neat and clean, when they went; and what more would the people have!’6

Branch workhouses were unique to London. The fictional workhouse in Oliver Twist has been supposed to be located about seventy miles north of London from two things: a milestone Oliver sees when he runs away, and his entry to London in the book via Barnet, which stands on the Great North Road.7 But the fact that baby Oliver is sent after weaning for rearing at a branch workhouse, before being brought back to the main workhouse and apprenticed out, reveals that Dickens was actually thinking of a metropolitan setting. The presence of a branch workhouse in Oliver Twist is fundamental to an understanding that Dickens’s seventy miles are completely fictional: Oliver’s days on the road are part of the allegorical journey of the book’s original subtitle, ‘The Parish Boy’s Progress’.8

The baby farm in Oliver Twist is placed ‘three miles off’ from the workhouse itself, which under Hanway’s Act was the regulation minimum distance for a branch workhouse. It is not known if the image of the St Paul Covent Garden Infant Poor Establishment labelled ‘British Pauper Children Asylum’ which appears in the caricature ‘Select Vestry Comforts’ bore any real resemblance to the actual place, though that is certainly possible since the artist was on target with so much else in the caricature. It may simply have been designed to appear as a farm building so as to refer to its baby-farming activity, which Londoners would have known would be in the fields. The place is shown as a barn-like building on a hill, surrounded by a wall, and with a large millstone leaning against it, the deeper meaning of which is explained by Dickens, when Mr Bumble describes Oliver as a ‘porochial ’prentis, who is at present a dead-weight; a mill-stone, as I may say, round the porochial throat’.9

Pauper children from the parish Workhouse of St Paul Covent Garden in Cleveland Street were actually sent out after weaning to the parish’s branch workhouse which stood in the old hill village of Hendon, north of London, over whose fields the battle of Barnet was fought.10 The mistress of the institution in Dickens’s time was a Miss Merriman; in the book this figure is named as Mrs Mann.11 Old manorial field maps show that at the heart of Hendon village was a milestone showing the distance to Charing Cross: known and labelled as the ‘seven mile stone’.12 In placing Oliver seventy miles away in the book, Dickens may simply have inserted a zero: he may have disguised the place very well indeed by adding nothing.

For Dickens, seven miles was an easy walk—up to Hampstead, and through North End (which he knew well) and Golders Green to Hendon village. Hendon churchyard, which had a magnificent view, was a favourite haunt of his.13 Dickens’s passion for active excursions was not that of everyone, however, and the distance does help explain the cost of the coaches hired to carry the Select Vestry of St Paul Covent Garden out to Hendon and back in the caricature, and Mr Bumble’s need for a drink of the parochial gin-and-water upon his arrival. Hendon was clearly on Dickens’s mind, too, as he was writing the novel, because during Bill Sikes’s flight after murdering Nancy, the killer thinks of the village as ‘a good place, not far off, and out of most people’s way’. But when Sikes gets there, even ‘the very children at the doors’ look at him with suspicion.14 Dickens would probably have known that some of the child population of Hendon in 1837 would have been what he ironically described as ‘juvenile offenders against the poor laws’, from Cleveland Street.15

Wincing with discomfort from the bad publicity caused by the caricature, the chastened Covent Garden parish authorities demonstrated their new probity by establishing a subcommittee to advise on the ‘revision’ of the administration of poor relief in the parish: the sting redounded on the poor. The recommendations of this committee were applied in 1830–1, while Charles Dickens was living in Norfolk Street. If news got out around the neighbourhood, the keen young journalist would have heard it.

Part of this ‘revision’ of the Workhouse in Cleveland Street reflected a broader shift in attitudes towards poverty. Rising population, and the number of widowed and deserted families from the Napoleonic Wars, as well as urbanization and the piecemeal eviction of the rural poor during the enclosure and clearance of estates, had swelled the population of London alarmingly. Metropolitan parishes especially were stretched to alleviate the levels of homelessness and want within their boundaries, especially during winter. Many politicians were persuaded by the ideas of Thomas Malthus that poor relief merely encouraged the poor to breed. Unmarried mothers and their offspring should receive the brunt of the blame for rising poor-rates, not errant fathers. Indeed, some influential figures went so far as to accuse all institutions which assisted childbirth among the poor (such as the lying-in charities) or those offering charitable care to the orphan poor (such as the Foundling Hospital) of encouraging immorality: they were to be regarded as altogether pernicious.16

Opponents of these harsh and uncharitable opinions raised kinder voices, urging solicitude towards the less fortunate. A correspondent in the London Journal, for example, cited especially the plight of ballad singers, whose desperate state had brought them to this last stage of existence before applying to the parish. The writer ascribed their pitiful vocal efforts to hunger: ‘I hear the notes falling like drops of lead’. Children who joined their voices to those of street singers are described in such a way as to remind one of the photographs of children saved by Dr Barnardo from the streets of late Victorian London, or the gangs of street children in Third World cities today:

half a dozen of the poorest squalid little creatures; and yet they sang, or attempted to sing, with all their might, though their cheeks were pinched by famine, and their uncovered little toes were smarting with the cold mud of the street.17

Readers will surely have no difficulty in knowing where Dickens stood on these matters, and what his views would have been concerning the extensive industry called ‘farming’ the poor. Private companies were positioning to offer themselves as contractors in warehousing the poor more cheaply than parishes might manage themselves. One such company sent advertising handbills to a number of London parishes in 1830 offering to ‘farm’ their female poor for only four shillings a week each, including washing and medical attendance, lying-in women at no extra cost. Remember, Dickens had been paid six shillings a week at the blacking factory, and had often been hungry. The company’s private workhouse in Lant Street, Borough, was advertised as capacious, clean, and airy, and the thin diet laid out as a Bill of Fare: on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, merely gruel and bread, on other days, a little meat or soup.18 That such painfully meagre (malnutrition level) alternatives to existing workhouse provision could be proffered to local authorities without shame indicates the punitive attitudes towards the poor these contractors were hoping to meet and satisfy. Many London parishes, including St Paul Covent Garden, did use these places as reservoirs for their own recalcitrant poor, and Poor Law authorities perhaps gained courage from such starvation dietaries to shrink their own.19

Attitudes were polarizing at the time: sympathy for the lot of the poor was giving way in powerful places to a level of harshness and unconcern previously unknown. At the time, a wave of political agitation was running in favour of much greater democracy, both nationally and locally, and huge numbers of people were mobilizing in support of parliamentary reform. But in many quarters this movement fed old fears of the Gordon Riots of 1780 or of the French Revolution, and many supporters of reform recognized the need to extend the franchise so as to prevent revolutionary fervour. So while the idea of greater democracy had wide support, part of the push for change had a hard edge of parsimony and retrenchment on the part of property owners, of pulling up the ladder. The economics of poor relief were bearing heavily upon the classes just above the very poor, who were voteless, and disgruntlement was widespread. The government eventually did slightly extend the franchise, in the Reform Act of 1832, which was widely hailed as great victory on its passage; but the voting qualification had been very carefully set at a property valuation of £10 sterling, which still excluded the vast majority of the population. Then came the New Poor Law.

Most localities in this era went through only one major upheaval in parish poor provision, when the 1834 New Poor Law was put into force, bringing in ‘unions’ of parishes, punitive workhouses, the enforced break-up of families, and rigorous ‘tests’ for poor relief. But in some places the political will to alter the administration of poor relief pre-dated the drafting of the new law, and retrenchment was introduced well in advance of its passage through Parliament. These parishes had a second period of change when adopting the New Poor Law after 1834. St Paul Covent Garden was one of them.

Under the New Poor Law’s process of reorganization and the amalgamation of parishes into ‘unions’ for reasons of greater economy, the Cleveland Street Workhouse was designated as the main workhouse for a new union of parishes in the Strand district, and its name was therefore changed to the Strand Union Workhouse. The appointed day for the adoption of the New Poor Law in the Strand Poor Law Union was 24 June 1836. Dickens began writing Oliver Twist within a year of its operation.20

To allow his hero to grow up from birth in a workhouse, and to become a parish apprentice and trainee thief within the time-frame of the novel’s serialization during 1837–8, Dickens set the story back in time. So although when it was written, the book was a bold attack on the spirit of the just-being-implemented New Poor Law, the fictional workhouse at the opening of the story was one where rigorous parsimony was already in force ahead of the Act itself: where the spirit of the new legislation was at work before the fact, yet where there were still signs of the Old Poor Law in operation. Some writers on Dickens have thought he was deliberately vague and confusing about the timescale of the book, but in fact when we look at the Cleveland Street Workhouse we can see that it fitted the bill well. Covent Garden was one of those parishes where change had arrived in two stages, and where the second stage was the New Poor Law, which served simply to reinforce the first.21

The Covent Garden Vestry’s Report on the implementation of the first phase of reforms at Cleveland Street in 1830–1 reads almost like a source-book for the opening chapters of Oliver Twist. The parish subcommittee had evidently grappled with the fundamental problem of what a workhouse was really for—sanctuary or punishment—and had come down in favour of the latter. There was no notion of sympathy for, or even recognition of seasonal unemployment, or of the deep dips of mass unemployment caused by recessions or trade cycles, or of the sheer helplessness of babies, children, the sick, the disabled, the elderly, or the dying. The divide for them was straightforward: between deserving and undeserving poor. Neither would be provided with anything more than bare subsistence. The Workhouse was to provide the absolute minimum: to shelter and sustain those ‘who are ready to perish’. The Workhouse should be:

a suitable Asylum for the aged, the imbecile, the unfortunate who are without friends to supply their wants, and whose means are wholly inadequate to their support, while their bodily or mental powers are too far spent to enable them to procure the sustenance, clothing or the shelter which nature requires. While to those whose mental or physical powers remain in sufficient vigour to enable them to secure by their labour the means of support, but who from idle, disorderly, or thriftless habits, have reduced themselves to merited indigence and disgrace, your Workhouse should be for such a place of wholesome restriction and discipline … [as to] convince such individuals of the propriety of providing the means of their own support by their own industry elsewhere.22

First, the Workhouse master and matron were replaced with a younger couple ‘without any objectionable incumbrance’, that is, having no responsibility for children or aged parents themselves. The committee then tackled the matter of gendering the institutional space, cutting off all communication between the men’s and the women’s sides of the building, thereby separating married couples, and disallowing meetings even at meals. The committee recognized at the outset that the architecture at Cleveland Street did not suit the asymmetry of its population: ‘the number of female poor, is nearly double that of males.’ Separation involved some building work and the locking of doors in strategic places, for the assignment of separate stairways, dining areas, and workrooms. The turning of keys firmly in the Workhouse locks is almost audible.

The committee’s report then concentrated on the curtailment of the Workhouse diet, listing in the ‘new-modelled diet table’ gruel every day for breakfast, and an allowance of bread (no mention of butter, or dripping) with a portion of boiled meat on Sundays, Tuesdays, and Thursdays, with soup on each day following, made from the broth in which the meat had been boiled. On Saturday neither meat nor soup, but a small portion of cheese, and with butter available instead only for the young. Tea, sugar, porter (ale), mutton or mutton broth, were permitted only on a doctors’ prescription.

The dietary looks to have been only marginally better than the pauper-farmers’ advert, and its indulgences reveal the true niggardliness of the regime: boiled mutton once in six weeks; pork and baked plum pudding once a year on Christmas Day with a pint of porter, and ‘cross buns one to each on Good Friday’. Unless expressly prescribed by the Medical Attendant, and entered by him in the ledger devoted to that purpose, it was specifically emphasized twice that there was to be: ‘no addition to the above allowance in any case’, and ‘on no account any additional allowance to be given’. If Dickens had seen this document, the idea of the terrible workhouse transgression of asking for more would have jumped off the page.

The Workhouse in Cleveland Street was cleaned and whitewashed, the separation of the sexes accomplished, and the new Workhouse dietary introduced. New regulations had been devised and enforced to ensure that while ‘reasonable comfort’ was available to the deserving and helpless poor, the Workhouse was rendered ‘undesirable to all who could support themselves by their own labour elsewhere’. Punishments were devised for ‘refractory’ and ‘obstinate’ paupers, which included being sent to the refractory ward (otherwise known as the ‘black hole’), half-diet, being ‘sent away’, and if necessary, being taken before the local magistrate for further punishment. Being ‘sent away’ for adults probably meant being sent to one of the existing privately run pauper ‘farms’, several of which by 1832 had as many as 500 ‘undesirables’ as inmates.23

Children (except in cases of misconduct) were permitted to walk out and enjoy a half-holiday every Saturday ‘under the superintendence of the School Master’, but adults were to have only one half-day in six weeks. Visitors were permitted only once a month, on the third Wednesday in every month, ‘between the hours and 10 and 12 in the forenoon’. There was no discussion as to how working people might visit relatives or friends on such a mid-week work day: one gains the impression that this morning had been deliberately chosen to curtail the possibility of visits. By locking the wards during the day, the subcommittee had been able to save money on coal. After daily prayers (‘the consolations of religion’) at 7.30 and gruel, the inmates were to be kept at work in the workrooms until 5 p.m. in winter and 6 p.m. in summer. For two hours every morning, boys were to be taught reading and writing; girls scouring, washing, ironing, mending, and cooking. All the bed-sacking, and all the linen of the house (including the paupers’ uniforms and burial shrouds), were to be produced in-house.

The committee reported that at no time had they lost sight of ‘the great object of Economy’. By the ‘rigid enforcement’ of the new parish regulations, they proudly announced that they had saved nearly £200 per quarter, especially by ‘cutting off the tea and sugar, which under the former practice had been allowed to all above 70 years of age’.

We do not know how open or closed the Workhouse was in terms of news on the street, but because Mr Dodd dealt in both tea and sugar, the grocer’s shop is likely to have been a route of news about the dietary and other changes afoot if visitors came to obtain supplies for inmates, or if employees came to purchase little luxuries for themselves.24

Charles Dickens was still living in Norfolk Street while this first tranche of institutional change was being implemented inside the Workhouse on the next block. He said years afterwards that he was ‘not eighteen’ at the time he became a Parliamentary Reporter, which dates this important transformation in his working life to the same period at which we are looking, while he was in Norfolk Street: 1830 or early 1831.25 He was probably working on his uncle’s Mirror of Parliament, initially trying to get up to speed to become a professional salaried newspaper staffer, which indeed he eventually succeeded in doing.26. But a lack of firm evidence has led some biographers to be vague about the date of his entry to the Reporters’ Gallery in the old Houses of Parliament, and some ascribe it to the more certain time of his work on the newspaper The True Sun, from March 1832 onwards. Either way, he would have witnessed the tail end of the stormy passage through Parliament of the Great Reform Bill, and would have been without work during parliamentary recesses, which were many during the political upheavals of that time.27

In the late spring or early summer of 1831, Dickens’s father again fell into financial difficulties, and for a period ended up ‘going to ground’—living alone in hiding—presumably to prevent being rearrested and imprisoned again for debt. There is good evidence for a similar episode in 1834, when John Dickens was arrested and held again in Cursitor Street (near Chancery Lane), and was freed by his son’s efforts.28 It is possible that a similar train of events had occurred in 1831. It looks as though the family fled Norfolk Street in a hurry, probably to evade creditors, apparently changing address several times. The fearful possibility of returning to the Marshalsea must have been serious.29 But Dickens renewed his own Reader’s Ticket at the British Museum from 10 Norfolk Street in May 1831, so the evidence for that year is difficult to read, unless he had gone back, or continued to use that address for reasons of stability.30

Family tradition says that in 1831 (perhaps later in the year) Dickens also shared rooms in Buckingham Street, Strand, with J. E. Roney, a reporter on the Morning Chronicle. Buckingham Street (which still runs south from the Strand, near Charing Cross) would have been very convenient for the journalism and parliamentary work in which Dickens was increasingly involved. The story goes that Dickens gave David Copperfield his rooms there: in a letter written years later, Dickens himself invited his friend’s recognition of the use he had made of them in the novel.31 This may have been a significant time for him: Dickens looks to have been earning enough independent income to rent his own living space, at least for a while: his first period living away from his parents since the blacking factory. Once again, he was down between the Strand and the River: he would have been able to see the site of the old blacking factory at Hungerford Stairs from the river end of Buckingham Street, so his pervasive sense of the Marshalsea period together with the cluster of associations of the Strand, Norfolk Street, and the blacking factory are likely to have been reinforced.32

Although Dickens was no longer living beside the Workhouse, the part of eastern Marylebone he knew so well remained a stamping ground for him, because even after his parents and the rest of the family had vacated the rooms above Mr Dodd’s shop, they remained strongly attached to the area. Documentation is thin, but apart from places to which they had to flee to evade creditors (near the Strand or out at Hampstead) the family’s known addresses over the next few years are all in Marylebone. During John Dickens’s debt crisis in 1831, the family was scattered, but by the late spring of 1832 the whole family was back together, living in Margaret Street (just south of the Middlesex Hospital); then for the rest of that year, in Fitzroy Street, just behind the Workhouse. In January 1833, they settled in Bentinck Street, off Marylebone Lane, where Dickens’s 21st birthday was celebrated ‘with quadrilles’.33

To be a Gallery Reporter in Parliament was something Dickens had intensely wanted to do, worked hard to achieve, and something at which he became superbly accomplished. Among its eighty or ninety reporters he is said to have occupied ‘the very highest rank, not merely for accuracy in reporting but for marvellous quickness in transcribing’.34 Dickens is likely to have entered upon the job with high hopes in 1831, but it is certain that he was wearied of it by the time he left in 1836. Forster puts it well: ‘his observation while there had not led him to form any high opinion of the House of Commons or its heroes … he omitted no opportunity of declaring his contempt at every part of his life.’35

It was Dickens’s destiny to witness the ascendancy in Parliament of similar attitudes to those we have just seen triumph in the management of the Workhouse in Cleveland Street. In 1831 the government appointed a Royal Commission to examine the workings of the Old Poor Law. The Commission’s harsh recommendations were enshrined in the New Poor Law of 1834.36

The central feature of the New Poor Law regime would be the ‘Workhouse Test’ (devised by Edwin Chadwick) which provided that the workhouse would become the only kind of help offered to anyone seeking assistance, and that the standard of relief there should be worse than the standard of living of the poorest labourer outside. It was this philosophy that Dickens characterized as having been devised by someone whose ‘blood is ice, whose heart is iron’.37 People could be offered the House; if they refused it, they could suffer at their own choice outside; if they accepted it, they accepted the regime on offer. Large workhouses were to be established by unions of parishes, not as humane refuges for the sick and elderly, but as deterrent institutions designed to be inhospitable to the ‘able-bodied’. No unemployment pay, district nursing, or other help was to be available even in times of high unemployment, dearth, or temporary desperation, and a key element of the regime was to prevent procreation. Dickens would have been well aware of the Royal Commission and its recommendations, which were published by order of Parliament in 1834. All this was in the air around Westminster during Dickens’s time there.

Dickens was in the Reporters’ Gallery recording in shorthand and re-transcribing word for word into longhand what politicians had said during some of the debates on the Great Reform Bill in 1831 and 1832 so he is likely also to have heard and reported upon the debates concerning another important piece of legislation, the Anatomy Bill, which went through both Houses of Parliament at that time.38 The battle over the Reform Bill extending the franchise and abolishing ‘rotten boroughs’ attracted extensive coverage in all the newspapers of the day, while the Anatomy Bill received almost none: partly because it was crowded out, but also because for political reasons it passed through most of its parliamentary stages late at night.

The Anatomy Bill was a measure designed to prevent body-snatching and murder for dissection. An earlier bill with the same intention had been thrown out by the House of Lords at the time of the first wave of burkophobia in 1828–9.39 That version had been nicknamed the ‘Midnight Bill’, because it, too, had made its passage at night.40 The new Bill was more deftly drafted, and had been ready for introduction to the Commons when news of the Italian Boy’s murder hit the headlines.

Under existing law, the only legal source of corpses for dissection in anatomy schools had hitherto been the gallows: the bodies of murderers were handed over after execution. But there were insufficient corpses available from judicial sources to supply the schools, so since at least the mid-eighteenth century body-snatchers had been paid to obtain them from graveyards. Their job was dangerous, public opposition was fierce, and danger money was payable. Eventually, the level of remuneration commanded by body-snatchers reached such a high level that some wretches (Burke and Hare, Bishop and Williams, and probably others never caught) came to regard the money as an incentive to murder.

The Anatomy Bill was designed to completely undermine this market and render body-snatchers and burkers redundant by the provision of a new free source of corpses. The first draft of the Bill had been explicit in naming who the new constituency for the slab would be: the workhouse poor. Effectively, the proposal was to make a direct transfer of what for many centuries had been a punishment for murder, to poverty.

The first Bill had earned itself the opposition of charitably minded MPs and Lords, and it failed. The new version, whose progress Dickens would have witnessed, was instead carefully evasive. It appeared innocuous by conveying the positive impression that its intention was to allow executors to donate bodies for dissection. In fact, the intention was identical: it simply granted to those legally ‘in possession’ of the dead, the power to dispose of them, and workhouses and other institutions in which the poor died were technically deemed to be ‘in possession’.41 The Bill made its way successfully through both Houses by a deliberate policy of downplaying its significance, known as ‘taisez-vous’ (or ‘shut-up’) where even staunch supporters were warned to keep quiet.

But the politicians did not have it all their own way: the intention of the legislation was vilified in a caricature by ‘Paul Pry’, in which the new sources of corpses for anatomy were shown in detail. Its central vignette shows deals being done between institutional employees and body-snatchers in a busy marketplace between a cluster of buildings labelled ‘WORKHOUSE’, ‘HOSPITAL’, ‘JAIL’ and ‘KING’S BENCH’, which last may have promoted a close personal appreciation of the legislation on Dickens’s part, perhaps a recognition of kinship with workhouse inmates.42 Dickens may be commenting upon such deals when he has Mr Bumble help himself to snuff from the undertaker Mr Sowerberry’s proffered snuffbox, which takes the form of a patent coffin—a symbol of secure burial for those with money to pay for it—but also a reminder of the threat of dissection—during a conversation about profit-making from pauper coffins.43

The Anatomy Act, which became law in the summer of 1832, perfectly complemented the wishes of those who were planning to bring in the new ‘deterrent’ workhouse system. In fact the Anatomy Act can be thought of as an advance clause of the New Poor Law, because it yoked together the terrible fear of dissection, which had been cultivated by legislation for centuries, and death in the workhouse.44 A pauper’s funeral now meant not just a workhouse shroud, a thin deal coffin, and a hurried burial in a pit behind the workhouse: it meant being treated like the worst of murderers. The same ‘Paul Pry’ caricature portrays the contrast between a safe vault for the rich and a poor man’s grave then, and now. The image is of traditional churchyard rest versus a dunghill (‘desected [dissected/desecrated] remains may be shot here’) with a dog/fox and a pig rooting about amid human remains, watched by a carrion crow; or, sold in joints at a street butcher’s stall.

The atmosphere of this dark time stayed with Dickens. Twenty years later, in a powerful editorial in Household Words, he described five bundles of rags he had witnessed lying against the workhouse wall in Whitechapel. He and his friend Albert Smith (with whom he had just had a convivial meal) did not realize at first that these heaps were human beings shut out of the workhouse:

Crouched against the wall of the Workhouse in the dark street, on the muddy pavement-stones, with the rain raining upon them, were five bundles of rags. They were motionless, and had no resemblance to the human form … five dead bodies taken out of graves, tied neck and heels, and covered with rags—would have looked like those five bundles upon which the rain rained down in the public street.

Dickens nipped inside the gate adeptly when it was opened, and sent in his card to the workhouse Master. The workhouse was full.45 Returning outside, Dickens woke the poor souls by the wall to give each money to find food and lodging. The association between these poor human heaps, the workhouse wall, and body-snatched corpses is eloquent indeed, and would have been grasped by his readers. Dickens asked rhetorically: ‘Stop and guess! What is to be the end of a state of Society that leaves us here!’, and in his own voice, concludes in exasperation:

I know that the unreasonable disciples of a reasonable school, demented disciples who push arithmetic and political economy beyond all bounds of sense (not to speak of such a weakness as humanity), and hold them to be all-sufficient for every case, can easily prove that such things ought to be, and that no man has any business to mind them. Without disparaging those indispensable sciences in their sanity, I utterly renounce and abominate them in their insanity; and I address people with a respect for the spirit of the New Testament, who do mind such things, and who think them infamous in our streets.46

There was bitter popular opposition to the proposed anatomy legislation, as there was to the New Poor Law, but the constituency of its victims was voteless, and politically insignificant. The new anatomy legislation disarmed charitable opposition by releasing the rest of society from fears of being body-snatched themselves, and by confining dissection to an institutionalized group, isolated and socially spurned. It was the clearest illustration of the scapegoating of the poor that the era could provide, and the clearest indication that entering a workhouse was to become a kind of social death. In 1831 dissection was a deliberate aggravation of the death penalty, a fate worse than death, inflicted upon Bishop and Williams for their bestial murder of the Italian Boy. In 1832, by Royal Assent, it was imposed on the institutionalized poor.

Through the Reform crisis in 1832, Dickens worked for several months as a Parliamentary Reporter on a radical newspaper called the True Sun. That December, a report of an inquest in London’s East End appeared in the paper, which appears to have been written by a penny-a-liner attending there ‘on spec’ for a good story. The inquest concerned the body of young woman, Polly Chapman, or ‘Handsome Poll’, who, being unable to pay her rent, had drowned herself after having been turned out of her lodging. The Coroner was asked by a churchwarden if he might legally give up the body to the London Hospital, as it was not claimed by any relatives, and the Coroner agreed as an example to prevent suicide among ‘unfortunate women’. The report continues:

Several of the latter class of females, who had conducted themselves with great decorum during the proceedings, here begged with tears and the greatest earnestness, to be allowed to pay a mark of respect to their unfortunate companion, by burying her in consecrated ground, for which purpose they had already raised £3.0.0 by subscription, and given to an undertaker. They described her as of the best and most inoffensive disposition, and incapable of injuring anyone.

The coroner, however, replied that it was necessary to make an example. The spirit of the Anatomy Bill would not be acted up to if the body was not given up. Any resurrectionist might claim the body as a friend, and afterwards sell it. A Juror said he thought the London hospital had bodies enough from the poor-houses; and that the poor creatures present had shown much good feeling, and ought to have the corpse. Mr Wilson, the Overseer, wished to take the sense of the Jury on the subject. After such discussion, it was decided that the body should be sent to the hospital. The announcement of this decision was received with the most bitter lamentations by the females, who appeared much attached to the deceased.47

Although Parliament was in a long recess at this time (August 1832 to January 1833) it’s unlikely this report was by Dickens: the inquest was heard in East London some way from his usual territory, and furthermore Dickens was busy working as a poll clerk for a politician in Lambeth in December 1832, which gave him paid work for some weeks.48 But he may well have read this piece, which is likely to have been written by someone he knew. The sensibility of the reporting is quite Dickensian, in so far as it is written with such skill that one can read it as an objective record and nevertheless sense the reporter’s views on the matter, and thereby sympathize with the lamentations of Polly Chapman’s unfortunate friends.49

Two vignettes in the ‘Paul Pry’ caricature anticipate similar moments; in one a weeping old woman is told: ‘The Body of your Daughter—you ain’t going to Gammon me—I’m not to be done out of my dues—we sold her’; in the other, a fat overseer answers the expostulations of a poor man: ‘Your Friends, eh? Do you suppose we are to keep a parcel of rascals in our House to be Buried like their betters?—No no, they are cut up long before.’ As Dickens has Mr Bumble comment to Mrs Sowerberry: ‘What have paupers to do with soul or spirit? It’s quite enough that we let ’em have live bodies.’50

Although the report concerning Polly Chapman was probably from another hand, it may be worth saying that it demonstrates that the True Sun allowed its journalists a measure of licence to express their own views critical of prevailing policies, which was completely lacking in the direct transcriptions Dickens had been producing for the Mirror of Parliament, and which he may regretfully have had to relinquish when he went to work on salary at the Morning Chronicle, whose proprietor was a staunch supporter of the New Poor Law.51 Dickens is known to have had many arguments with that newspaper’s Editor about the politics of the Poor Law.52 The necessary suppression of his own humanitarian sympathies in his journalism at the Morning Chronicle may eventually have helped prompt Dickens to write his Sketches. What was proscribed in one place grew to flourish in another: his ideas and commentary were fashioned into freelance essays; observations on the streets and in police courts, pickpockets, a hospital patient, low life, London characters and institutions, and in the process, Dickens was making the transition from description to fiction.53

The successful passage of the Anatomy Act demonstrates that the political alliances that created and passed the punitive legislation of the early 1830s repudiating the poor were effective inside both the unreformed and the ‘reformed’ Parliament. As a Gallery Reporter Dickens would have been closely aware of the process by which the Reform Act and the Anatomy Act (both 1832) and subsequently the New Poor Law (1834) made their parliamentary passage.

Through the onerous manual and mental work involved in processing their privileged words, Dickens had a good grasp of the thought-processes of those who held power. After he had left the Gallery, Dickens said that he had been there ‘a great deal too often for our own personal peace and comfort’. His antipathy suggests that he may have felt implicated or sullied by the association.

The punitive new system introduced by Parliament in 1834 failed to differentiate between the work-shy and the disabled, the sick and the well, the feckless and the old, infirm or the infant child: all were treated alike, and all blameworthy. When he chose the term ‘parcel of rascals’ in the caricature, ‘Paul Pry’ characterized the attitude with precision.

Dickens’s anger at the brutalization of the workhouse system eventually emerged in the biting satire of the opening chapters of Oliver Twist. Simply by showing the birth and institutional rearing of such a child, he addressed head-on the cultural failure of imagination he had witnessed among Parliamentarians as to what it might be like to be born in a workhouse, ‘to be cuffed and buffeted through the world—despised by all, and pitied by none’.55 The sheer brutality of the system is exposed by the story. Through no fault of his own (other than breathing) Oliver is neglected, exploited, threatened with being devoured, maligned, threatened with being hanged, drawn, and quartered; he is starved, caned, and flogged before an audience of paupers, solitarily confined in the dark for days, kicked and cursed, sent to work in an undertaker’s, fed on animal scraps, taunted, and forced to sleep with coffins.

The book opens with Oliver’s birth: his mother Agnes, we learn, had been on her way to his father’s grave when she herself is found moribund on the street, and taken to the workhouse to die. Her poor corpse is preyed upon after her death by the woman who lays out the body, who steals her locket. Although at the book’s end a monument is erected to her memory, it does not mark a grave. Dickens makes clear that her identity was unknown, which is why Oliver is given a completely fictitious name by Mr Bumble, who goes to some effort to discover his mother’s origin:

‘And notwithstanding a offered reward of ten pound, which was afterwards increased to twenty pound. Notwithstanding the most superlative, and, I may say, supernat’ral exertions on the part of this parish,’ said Bumble, ‘we have never been able to discover who is his father, or what was his mother’s settlement, name, or condition.’56

Oliver Twist began publication in 1837, the New Poor Law had been law since only 1834, and the Anatomy Act since 1832. Contemporary readers would have understood that the body of Oliver’s mother was unclaimed. The disappearance of her corpse is explicitly stated in the book’s final paragraph: Dickens emphasizes the absence of her body: ‘There is no coffin in that tomb.’ It is part of the subtext of the novel that the poor young woman who dies in its opening pages was being dissected while her son was being starved.

It is a measure of Dickens’s genius that he does not name the New Poor Law in Oliver Twist and he neither names nor mentions the anatomy legislation either, although the first time we meet Bill Sikes he threatens to burke Fagin. Having kicked his dog across the room, Sikes turns to make the threat:

‘I wonder they don’t murder you; I would if I was them. If I’d been your ’prentice I’d have done it long ago; and—no, I couldn’t have sold you arterwards, though; for you’re fit for nothing but keeping as a curiosity of ugliness in a glass bottle, and I suppose they don’t blow them large enough.’57

This is Dickens letting us know just what kind of hands Oliver has fallen into, and its brutal equivalence to the New Poor Law workhouse system, which, while he was writing, was being implemented in Cleveland Street. Dickens discreetly emphasizes the innocence of Oliver’s mother—‘poor lamb’ says the workhouse nurse—and the profoundly unchristian behaviour of the authorities in charge of her child: ‘ “They’ll never do anything with him, without stripes and bruises,” says the same gentleman in the white waistcoat as would have consigned him to Gamfield the sweep.’ Stripes and bruises—meaning lashes and blows—were inflicted as part of the sufferings of Christ.

In the Strand parishes the operation of the New Poor Law took a couple of years to plan and prepare, so although rumours were doubtless circulating and fears rising, it was not until after the day appointed for its implementation, 24 June 1836, that the impact began to be felt. The application of the new law was swift and harsh. Surviving documents show that although Divine Service was scheduled in the workhouse twice every Sunday, at 9 a.m. and 3 p.m., families were cast asunder as soon as the Act was adopted. Rules were laid down before 24 June that year to the effect that ‘all relief to non-resident poor is prohibited’, and within a month, even churchmen were learning the limits of their influence. When he remonstrated on behalf of a poor parishioner, Ann Nugent, the Reverend Richard Burgess of Cadogan Place received a polite rejection letter from the new ‘Guardians of the Poor’, who found a ready defence by taking refuge in the proscribed limits of their own powers: ‘had any deviation from the rule been allowable the circumstances of the case so forcibly stated by you would have justified such deviation’.58

By August 1836 the work of the Board of Guardians had been simplified by the drafting of a standard refusal letter for the Clerk to utilize for respectable correspondents who, like the Revd Burgess, had taken it upon themselves to remonstrate about the inhumanity of the new law in particular cases: ‘Some very strong cases of non-resident paupers have come before the Board and have ended in the same result.’

These cases most probably concerned elderly parishioners living with their own families, whom the little help the parish had given had previously helped keep them together. The New Poor Law insisted on no out-relief, so the elderly had no choice but to enter the workhouse, or the family was deprived of any help if they chose to keep them at home. If nursing the elderly occupied a wage-earner, or diminished home earnings, poor families who might try to keep their elderly at home could become impoverished by the effort.

The Strand parishes which formed the Strand Poor Law Union covered between them a considerable area of the heart of London: St Paul Covent Garden, St Clement Danes, St Mary-le-Strand, the Liberty of the Rolls, the Precinct of the Savoy, St Anne, Soho (up to 1868) and (after 1868) St Martin’s-in-the-Fields. The Strand Poor Law Union would remain in existence right through the rest of the nineteenth century, until the Great War. Families hitherto entitled to receive parish help to survive at home if the breadwinner was sick, were now broken up, and whatever belongings they had were sold to recompense the parish for their board and lodging. Soon after the New Poor Law was applied in the district, for example, John Powell was sent to Cleveland Street, while his wife Elizabeth was ordered to the old St Clement Danes Workhouse in Portugal Street; Daniel James went to Cleveland Street while Ann James went to Hendon; of the Jackson family, Thomas was sent to Cleveland Street, Mary to Portugal Street, and their children Henry and Mary to Hendon.

All the children from St Clement Danes Workhouse were ordered to be ready at first light on 24 June 1836 for transportation to Hendon, but it transpired that it was found ‘inconvenient’ on that day. There seems to have been considerable local opposition to the changes, as repairs were ordered on 30 June to ‘all the broken glass’, and the Police Office at Bow Street was requested to keep extra constables in the vicinity.

The guiding hand of the Poor Law Commission was felt immediately upon the local administration. The Workhouse Master was told if necessary he might disobey the Overseers, who were, he was told, ‘unknown to the Law’.59 It seems they were too kind for the efficient implementation of the Act, and had been deliberately written out of the operation of the new law in its drafting. Correspondence with the Commission’s Secretary, Edwin Chadwick—covering everything from seeking guidance concerning small gratuities for pauper nurses (refused) and the appointment of Porters, or gatemen—rapidly became grovellingly deferential.

The old gatekeepers, it seems, were too elderly, so they were sacked. The new ones were ex-policemen, who were required to be more vigorous as they were empowered to keep the peace at the workhouse gates, and when necessary to take offending parties into custody. The tone of voice in letters from the Poor Law Commission, stressing the danger of ‘disorder and laxity of discipline’ was peremptory: ‘even individual Guardians acting other than collectively at the Board have no … authority’, and rapidly infected the voice of the new Guardians: ‘immediately inform me by what authority you have allowed some of the Pauper Inmates of the Cleveland Street Workhouse to have a holiday today … no holidays are allowed under the new system.’60

Tradesmen felt the impact of the new regime too. A new weighing machine was purchased to ensure the parish was receiving goods as agreed per contract. Goods and services for the new Union of parishes were tendered for, and new rates agreed, many of them lower than before. The contract for parish coffins, for example, was awarded to John Dix, four feet and upwards at a shilling per foot, under four feet, sixpence per foot, shrouds included, less than the price paid in the 1790s.61 Dix later solicited a Guardians’ letter recommending him as official undertaker to the Inspector of Anatomy, so we can be sure that bodies from Cleveland Street were going to the medical students of the hospital across the way.62

Ratepayers would also have been made aware of the new regime, because rate-collectors were awarded sixpence in the pound for every amount collected under £20, fourpence if the amount was over £20, which ensured they focused on the bulk of smaller rate-payers. By July 1836, Cleveland Street was almost military in discipline: the Board Room must be ready prepared for a meeting of the Board of Guardians, staff were to be lined up at 6 p.m. in the Hall ready for inspection.

Inmates had been set to work making extra mattresses for Hendon, and new hammers were purchased for stone-breaking. Uniforms of brown Yorkshire cloth, with special buttons marked ‘STRAND UNION’, were instituted for all men and boys, and blue check dresses and aprons for all women and girls. The only exception to this uniformity of dress was for unmarried pregnant or lying-in women, who, during the entire period of their stay in the workhouse, were forced to wear ‘the yellow gown’. In bastardy cases, infants went to Hendon, and the mothers refused relief.63 A ban was enforced on paupers attending another hospital, or being allowed out of the house on any other pretext without the permission of the Board of Guardians sitting as a body; no pauper women might be sent to help at Hendon who had children there, and so it went on.64

FIGURE 34. The Empty Tomb, from the first edition of Oliver Twist. Oliver stands beside Rose Maylie, to contemplate the church memorial commemorating Oliver’s dead mother. Etched by George Cruikshank, 1838.

Dickens probably used the Strand Union Workhouse as his model not only because he already knew the workhouse well from having lived nearby, but also because it was an exemplary institution. The extent to which the authorities of the Cleveland Street Workhouse willingly adopted the dictates of the new law, and rendered it a model institution from the point of view of the new Poor Law Commissioners is revealed by a comment from Charles Mott, one of its own Commissioners, that the Strand Union: ‘for correctness and management and strict adherence to the rules cannot be surpassed by any Union in England’.65 Many other parishes in the London region did not embrace the new law so enthusiastically, in some cases remaining fiercely parochially independent until at least the 1850s. The Marylebone Workhouse, which was on the New Road west of Marylebone High Street (its site is currently occupied by the University of Westminster) was quite unlike the Strand in its refusal to collaborate with the new regime.66

Dickens is strictly accurate for Cleveland Street in some of the details he uses in Oliver Twist, not only in small domestic matters such as the iron bedstead in which Oliver’s mother dies, and the brown cloth of the workhouse uniform Oliver wears, but in real events. For example, Oliver narrowly avoids being sent out to become a chimney sweeper’s climbing boy, but two boys from Cleveland Street, Thomas Jackson and John Woodward, were actually sent out ‘on liking’ to chimney sweeps in August 1836, and in fact master sweeps seem to have been quite frequent applicants as employers of pauper children from the Cleveland Street Workhouse.67 It is evident, too, that as in Oliver’s case, exile and harsh employment were being used at Cleveland Street as forms of punishment for children like Oliver, who were labelled as ‘refractory’. In September 1836, the Guardians unanimously required the Workhouse Master to furnish: ‘names and ages of those boys and girls whose conduct is disorderly or refractory preparatory … for sending them to the Manufacturing districts to be employed in the factories under the sanction of the Poor Law Commissioners.’

We can see from this decision that the Strand Guardians were an ideal target for Dickens to use in the book, as they were identifying themselves so closely with the New Poor Law regime. Factory discipline seems to have been favoured under Edwin Chadwick at the Poor Law Commission, rather than the naval discipline of the Sea Service (Royal/Merchant Navy) from the Port of London, to which boys from other London parishes were more likely to be sent.68

Dickens is equally accurate in other matters. He has Mrs Mann banter with Mr Bumble:

‘by coach, sir? I thought it was always usual to send them paupers in carts.’

‘That’s when they’re ill, Mrs. Mann,’ said the beadle. ‘We put the sick paupers into open carts in the rainy weather, to prevent their taking cold.’69

which conversation is explained by a letter of August 1836, preserved in the Strand Guardians’ minutes, addressed to their counterparts at Kingston-on-Thames, concerning the ‘very irregular manner’ in which a sick woman, Margaret Wilkin, an inmate at Kingston Workhouse, but originally a parishioner of Clement Danes, had been carried to town in an open cart, and put down at the Elephant and Castle, despite being ill. Normally arrangements were made in advance, but in this case it seems no warning had been given, no arrangements made. How Margaret Wilkin eventually arrived at Cleveland Street is not explained by the letter, but the poor woman was evidently very poorly: ‘If death should ensue’ they were told, ‘your office would be clearly liable to be indicted for the offence.’70

No newspaper source has yet been found from which Dickens might have obtained this story, which suggests that Dickens may have known someone inside the institution, who was acting as his informant.71 So far, it is not clear who this person might have been, unless it was a disaffected employee from the old regime, which is possible after the sackings of the old workhouse master, matron, and gatemen. There is another possible source of information: one of the new guardians themselves. This idea is not as far-fetched as it may seem, as one of them, Valentine Stevens, worked as a law bookseller in Dickens’s old stamping ground at Bell Yard, Doctors’ Commons, and another, George Cuttriss, ran the Piazza Coffee House in Covent Garden, which we know Dickens frequented, and where the Guardians had their Christmas dinner in 1836.72

Dickens’s knowledge of accurate details from inside the Workhouse on Cleveland Street might also have been gained via Mr Dodd, who probably knew everyone on the street, or from the local publican of the ‘King and Queen’, which stands right opposite the Workhouse, who might have heard a lot of things while he was polishing tankards. It may be that Dickens kept quiet about his association with the street in order to protect someone still living there, and if this is the case, the publican is likely to be a possibility.73

Reading through the surviving documents, it is easy to see that while there might be written rules and regulations, and while these might or might not be rigidly enforced, no serious money had been spent to improve the facilities in the Workhouse to cope with the influx of desperate poor from the new conglomeration of parishes of the Strand Poor Law Union, or for the rearrangement of pre-existing human relationships which were now to be forced to fit the rigid boundaries and constrained charity of the new parish unions.

The records are very incomplete. From a long list of ledgers concerning the internal management of the House, including the Workhouse Master’s punishment books, the Gateman’s Day Books, and the Parish Doctor’s ledgers, all of which regulations specified must be kept by the various officers of the Strand Union, none remains. Yet from the New Poor Law Guardians’ minutes, some of which do survive, we can discern indicators of strain, such as a comment about the noxious effluvia from the men’s latrines in the Workhouse yard fronting onto Cleveland Street, and the ‘choaked’ privies at Hendon. From these it is possible to read between the lines of the Clerk’s formal script to think about the real lives of the people who were being herded out of central London into these places, and indeed, those who were stuck outside. By the last year of William IV’s reign, the New Poor Law had been implemented in the Strand Poor Law Union, and the stink was noticeable in Cleveland Street.