CONTEMPORARIES, SKETCHES, SPECTRES,

OLIVER TWIST, NA MES, ECHOES

CHARLES DICKENS was already the author of an impressive number of clever Sketches published pseudonymously in the press in 1836, when the New Poor Law was being implemented in Cleveland Street in 1836, He had moved away to live on the borders of the City at Furnival’s Inn, where just around the corner lay both Field Lane, where he would locate Fagin’s den, and Bleeding Heart Yard, which he would use later in Little Dorrit.1 Important events occurred that same year: his Sketches were collected into two volumes, under his pen name ‘BOZ’, and Dickens married Catherine, the daughter of his father’s friend George Hogarth.2 Then, the soaring popularity of his Sketches brought young Dickens the commission from Chapman and Hall to write The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, to be published in parts over the next couple of years.3 Michael Slater is surely right to describe 1836 as Dickens’s ‘break-through year’.4 ‘No writer ever attained general popularity so instantly as “Boz”’, said The Spectator in December 1836: ‘and certainly no-one has made such industrious use of his advantages … he is seized by the multitudinous hands of the public, and meets with a spontaneous and universal welcome.’5

‘Boz’ was appointed Editor of Bentley’s Miscellany in early November 1836, before he had finished with Mr Pickwick, and he resigned from his job at the Morning Chronicle the following day. Almost immediately, he began Oliver Twist.6 The book’s dramatic opening with the naked baby coming into the world was published less than a month after Dickens’s own first child was born at Furnival’s Inn.7

There had been another family upheaval when John Dickens was arrested for debt in November 1834, but not long afterwards, Dickens’s parents were back in Marylebone again.8 In 1836 they were in Edward Street (today part of Wigmore Street) and in March 1837 Dickens himself returned to live in the area, when he took lodgings for his own small family in Upper Norton Street (now Bolsover Street) between leaving Furnival’s Inn and moving into Doughty Street.

He returned again more permanently in 1839, when he took a large house at 1 Devonshire Terrace, at the top end of Marylebone Lane, close to the two churches of St Marylebone, old and new. Dickens settled his growing family there for over a decade until 1851, during which time he wrote all the major works of his middle years: The Old Curiosity Shop, Barnaby Rudge, American Notes, Martin Chuzzlewit, A Christmas Carol, The Chimes, The Cricket on the Hearth,

The Battle of Life, The Haunted Man, Dombey and Son, and David Copperfield. From this address, too, Dickens launched the Daily News, and Household Words.9 All the Marylebone addresses I have mentioned are within a short walk of Mr Dodd’s corner shop and the Cleveland Street Workhouse, and if one walked as briskly as Dickens is said to have done, the journey time would be briefer still.

Once one starts looking, it becomes noticeable that it would not have been easy for Dickens to keep too far away from the area for long because so many of his friends, and families of friends, lived there. Maclise, for example, lived in Pitt Street near the Middlesex Hospital, and then in Charlotte Street, and George Cattermole moved his home from the northern end of Cleveland Street down into Berners Street between 1826 and 1846.10 Samuel Lover lived in Charles Street, by the Middlesex Hospital.11 The Landseers, Augustus Egg, Frith, G. A. Sala, and John Hullah all had roots in Marylebone.12

Dickens came back for other reasons, too. Years afterwards, he mentioned in a letter to an actor, William Mitchell, that he had admired his performance in a play called The Revolt of the Workhouse at the theatre in Tottenham Street in 1834, when Dickens was living in Furnival’s Inn.13 The play was by Gilbert A’Beckett, a lawyer, prolific journalist, and playwright, who specialized in humorous periodical writing and theatrical burlesque.14 It was a Cockney send-up of a recent ballet called La Revolte au Sérail, the opening night of which had been only nineteen days earlier at Covent Garden. Instead of a revolution in an exotic eastern harem, A’Beckett’s version was set inside a London workhouse.15 Dickens had been planning a series of sketches—and perhaps a novel—on parish subjects since the time of his first published sketch in 1833, so no doubt he was intrigued by the play’s title.16 A’Beckett and Dickens moved in similar circles, and it is not at all surprising that both men should have been thinking of a workhouse theme in 1834, while the New Poor Law was progressing through Parliament.17

When the text of A’Beckett’s play was published in 1835, it had a frontispiece by Cruikshank, and opened with the verse from Dr Johnson’s London:

All crimes are safe but hated Poverty,

This, only this, the rigid law pursues,

This, only this, provokes the snarling muse.

A’Beckett’s preface proceeded to analyse different sorts of poor, one of which—since we are thinking about Oliver Twist—is perhaps significant:

a little urchin, whose parents (having been beggars) are dead; or else such as having run away from their masters, follow this strolling life. The first thing they learn is how to cant and the only thing they practise … is to creep in at windows or cellar-doors.

Another is a sturdy big-boned knave, who carries a short truncheon, and whose profession is to be ‘idle and vagabondical’. The master of the workhouse in the play calls himself the Workhouse King, and makes the female paupers kneel to him; the vain Beadle loves the lace that glitters in his hat, and his staff of office, and says:

That public justice may be well protected

’Tis right her officers should be respected.

The workhouse tea, made with half an ounce of tea-leaves for the entire workhouse ward, is the root of the trouble:

I’d say without compunction—

’Twas but a cup of neat Grand Junction

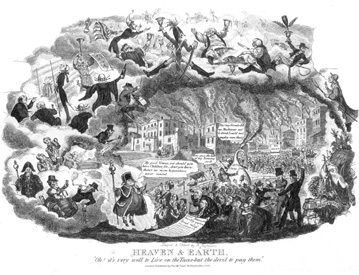

FIGURE 35. Heaven and Earth, an extraordinary complex and arresting image, created in 1830 by the artist Robert Seymour, the original illustrator of Pickwick Papers, who committed suicide in 1836, just as the popularity of Pickwick was mounting. Many details in this caricature suggest Seymour’s work may have influenced the young Dickens: his depiction of the soured relations between haves and have-nots, and his portrayal of seriously hard times: poverty, jobbery, parochial tightfistedness, unemployment, and hunger among the poor, while others were feasting. The central figure of the Parish Beadle could well have been a model for Mr Bumble, and his cockney idiom for Mr Weller’s diction.

FIGURE 36. (Overleaf) Old shops at Charing Cross, which faced the top end of Whitehall. A fine view sketched by George Scharf in 1830. This entire row was demolished soon after the drawing was made, for the construction of the south-eastern quadrant of Trafalgar Square. The stables of the famous coaching-inn, The Golden Cross, occupied the land behind these shops; its entrance was at their western end. Scharf records the variety of shops and wateringholes for which the area was well known, and the interest of their windows. The central shop is a silversmith and pawnbroker. Below, Scharf ’s marginal notes record the three golden balls and the legend of the shop’s signboard: ‘Money advanced on property’.

—meaning that it tastes like canal water. A revolt ensues and the workhouse clerk is soused in the laundry washtub. But A’Beckett’s revolt is a comedy with a happy ending. After a facetious battle, the female paupers win the day, and the police and the workhouse master sue for peace. The terms agreed are the provision of bread less than four days old, sugar for the inmates’ tea, and cheese ‘in any quantity the ladies please’. The show ends with a rousing chorus in which the workhouse inmates sing:

Let workhouse struggles end

And let the Beadle be the paupers’ friend.

What Dickens made of this almost pantomimic entertainment is anyone’s guess. He seems to have enjoyed the efforts of the actor Mitchell who cross-dressed to play Moll Chubb, one of the female leads. But since Dickens probably had a good idea about the full seriousness of what was in the parliamentary pipeline, he cannot have been as sanguine as A’Beckett about the likely outcome of conflicts inside such institutions in real life. Whether he was aware of the full details of what revisions had already been made in 1830/1 in the workhouse around the corner from the theatre we cannot be certain, although he was undoubtedly accurate in several significant respects when he came to write Oliver Twist.

Closer to his own turn of mind than the Gilbert A’Beckett play may have been the opening of a triple-decker novel (also of 1834) called The Pauper Boy by ‘Rosalia St Clair’ (a pseudonym) which opened with a death, and features a brutal workhouse master who is exposed and loses his job, but is reinstated because he has influence among the workhouse guardians. The book deteriorates into a religio-romantic novel, but its interesting start is noteworthy for a number of reasons, not least because the book is narrated by the solitary workhouse child at its centre, who is given a small ebony crucifix by his old workhouse nurse, which, she tells him, ‘may one day be the means of discovering your kindred’.18 The boy is sent out as a parish apprentice, to a Charing Cross pawnbroker and his wife, who emerge as sympathetic figures in the story, which allows the narrator to observe that ‘many a tale of broken-hearts and ruined prospects might be drawn from the records of a pawnbroker’s repository’.19 This woman dies before imparting the whole story. The boy is accused of a crime he did not commit, and meets a sympathetic woman who helps him by the stairs descending to the River by Westminster Bridge. He is later imprisoned with various low-life characters.

Dickens’s own series of Sketches on parish characters and parish matters had begun appearing in various newspapers and magazines in the early months of 1835, and continued through 1836. The Sketches are highly significant in Dickens’s development as a novelist, in a way not dissimilar to the manner in which, twenty years later, Scenes of Clerical Life allowed George Eliot to find her voice in fiction. Part of their charm for readers when they first appeared was that, while the Sketches were topical, they were also geographically vague: clearly London-based, but no one knew either who ‘Boz’ was, or exactly where his observations were being made. Part of the frisson of excitement was that Boz’s way of seeing, perhaps, served to encourage ordinary Londoners to see their own neighbours and neighbourhoods with a new acuity.

There is a possibility, now that Dickens’s association with the Norfolk Street locality is better understood, that originals for some of these tales may become traceable. So far, in only one case has a fictional character been found in one of Dickens’s Sketches who seems to relate to a real person: someone who lodged with Mr Dodd in Norfolk Street.

The Sketch Dickens entitled ‘The Dancing Academy’ is significant, since it prefigures the case of Bardell versus Pickwick—a breach-of-promise case—which occupies a central place in Pickwick Papers. Dickens presumably came across plenty of such stories at Doctors’ Commons, an ecclesiastical court dealing with such matters. ‘The Dancing Academy’ features the family of a dancing master with the unlikely name of Signor Billsmethi, and his luckless rather green bachelor pupil Mr Augustus Cooper, who is first charmed and then frightened into paying a large sum of money to his dancing master’s daughter under threat of such a case, even though the level of his involvement in any kind of courtship had been non-existent. In the story Dickens frankly denies that it has anything to do with the area of Marylebone in which we know he lived. The manner in which he does so, however, gives the impression of protesting too much. This is how he introduces the dancing academy:

Of all the dancing academies that ever were established, there never was one more popular in its immediate vicinity than Signor Billsmethi’s, of the ‘King’s Theatre.’ It wasn’t in Spring Gardens, or Newman-street, or Berner’s-street, or Gower-street, or Charlotte-street, or Percy-street, or any other of the numerous streets which have been devoted time out of mind to professional people, dispensaries, and boarding-houses; it was not in the West-end at all, it rather approximated to the eastern portion of London, being situated in the populous and improving neighbourhood of Gray’s-inn-lane. It wasn’t a dear dancing academy—four and sixpence a quarter is decidedly cheap upon the whole. It was very select, the number of pupils being strictly limited to seventy-five; and a quarter’s payment in advance being rigidly exacted. There was public tuition and private tuition—an assembly-room and a parlour. Signor Billsmethi’s family were always thrown in with the parlour, and included in parlour price; that is to say, a private pupil had Signor Billsmethi’s parlour to dance in, and Signor Billsmethi’s family to dance with; and when he had been sufficiently broken in, in the parlour, he began to run in couples in the Assembly-room.

This Sketch offers a rare instance in which Dickens names streets he would have known well from living in and around Norfolk Street: Berners and Newman Streets, particularly, but also Charlotte Street (the southern end of Fitzroy Street, behind the Workhouse) and Percy Street, parallel to Tottenham Street, south of Goodge Street. To map the area they indicated would have given a good idea where to find people who knew ‘Boz’, if one didn’t already know him. The ‘King’s Theatre’ was a play on the ‘Queen’s Theatre’, the name given to the old ‘Regency Theatre’ in Tottenham Street in the 1830s. The denials about the school’s location first led me to examine the dancing academies which did exist in the area, and to discover that there was a surprising number. That area north of Soho was well known as a musical and artistic district: it seems that fair-sized rooms that suited artists as studios and exhibition spaces because of their lowish rents could also serve for the tuition of dancing. A search for dancing schools near Gray’s Inn yielded only one in Hatton Garden. Blanks were everywhere concerning Signor Billsmethi, until the following entry in the London Gazette made me sit up. It concerned a man who became an insolvent debtor in 1840:

William Menzies, formerly of 10, Fludyer-street, Westminster, then of No.9 Charlotte-street, Bloomsbury then of No.10, Norfolk Street, Middlesex Hospital, then of No.47, Charlotte-street, Fitzroy-square, then of No.45, Regent-square, and late of No.9, Wakefield-street, Regent-square, Gray’s-Inn-Road, Music and Dancing-Master, and whilst residing at No.45, Regent-square aforesaid, his wife a Schoolmistress.20

Bill Menzies is not that far from Billsmethi, but it’s the biography that is so noticeable. Menzies had moved from a small house in Westminster to Norfolk Street, to the top end of Gray’s Inn Road—a shabby-genteel area north of the Foundling Hospital, actually not that far from Doughty Street.21 It looks as though this man and his family had been lodgers in Mr Dodd’s house, and ran a dancing school there, perhaps at the same time the Dickens family was living there for the second time. The noise of the music and footwork (especially of beginners) was probably not delightful to Mr Dodd, and probably not very beneficial for the structure of the corner house. The grandiose terminology for its modest living rooms—‘parlour’ and ‘assembly room’—is laughable, and Dickens’s addition of ‘Signor’ may suggest the assumed continental airs and graces of the man. We have no further knowledge from the London Gazette, of course, concerning the breach-of-promise thread of the story, which may have been grafted from elsewhere, or if true may perhaps have provided needed extra income (on more than one occasion?) for this sorry family on its way down towards the debtors’ prison. Dickens may have kept in touch with Mr Dodd, and heard the sequel.22

It used to be thought that Dickens kept no working notebook until late in life, but this surely cannot be taken to mean (as it seems to have been by some) that he kept no working notes.23 As a journalist he would have had to take notes, and as a reporter in Parliament, the reams of words he would have had to take down in shorthand, and then transcribe into fair copy for the printers must have required a lot of paper. Whether or not these notes took the form of a memorandum book, like the one that survives from the last decade of his life, seems not to be known.23 That Dickens drew strongly upon his own memory for places, faces, posture, tones of voice, and so on surely cannot be doubted, but I would hazard a guess that he kept notes throughout his working life. Someone recorded seeing him perched on a barrel in a bar, taking shorthand notes of men in conversation.24 A comment in a letter to Macrone, the first publisher of Sketches by Boz, supports this idea:

I find in some memoranda I have by me, the following Headings. ‘The Cook’s Shop’—‘Bedlam’—‘The Prisoner’s Van’—‘The Streets—Noon and Night’—‘Banking-Houses’—‘Fancy Lounges’—‘Covent Garden’—‘Hospitals’—and ‘LodgingHouses’—So we shall not want subjects at all events.25

In the small memorandum book that survives from the 1860s, we find Dickens making careful notes of ideas, things he’d seen or heard, turns of phrase he liked or recordings of moments he had witnessed which had made him laugh, scenes and sketches which existed in his imagination, but which he never wrote up.26 There are also long lists of names, and ways of playing with names, cutting them in half, looking for congenial syllables, trying permutations of suffixes and so on; such terminations as -straw -ridge - bridge -brook - bring - ring - ing are listed. Elsewhere, his working notes for David Copperfield show how the evolution of the name that we take for granted from his title was actually arrived at: ‘Flower—Brook—Well—boy—field—Well-bury—Copperboy—Flowerbury—Topflower—Magbury—Copperstone—Copperfield’—then underneath again, as if he was sure of it, ‘Copperfield’.27 How good it would have been to get sight of his running notes and memoranda for Oliver Twist.

Local names and street names in the Norfolk Street vicinity are very suggestive. Just across Charles Street from the bottom end of Norfolk Street, for example, in Berners Mews, were the premises of two tradesmen named Goodge and Marney. This same mews was close to the old home in Mortimer Street of the famous local miser, the sculptor Nollekens; the district was known for another miser, too, proud of his own dire parsimony and known as ‘The Celebrated Marylebone Miser’.28 Marylebone itself, incidentally, was sometimes mis-spelled (and often pronounced) Marleybone, and Marley was also a local name (another cheesemonger in nearby Titchfield Street, and there was another Marley shop board on Oxford Street), so it seems possible that Dickens played with the consonances of Marney and Marley before settling on the name of the Ghost in A Christmas Carol.29 The permutations of the name of the entire parish are many: Samuel Pepys called it Marrowbone, others, Maribone, and—taken with Mr Menzies’s sham title—we need not ponder long as to where Signora Marra Boni comes from in Dickens’s Sketch, ‘The Vocal Dressmaker’, especially as a female ‘Professor of singing’ occupied a house opposite Mr Dodd’s.30 Sowerby was the name of a publican in Goodge Street—not far perhaps from Oliver’s employer, Sowerberry the undertaker. A baker in Tottenham Street was Jonah Dennis, a surname Dickens used in Barnaby Rudge, and a tailor called Rudderforth lived and worked at 36 Cleveland Street, whose name led me to look again at a passage in David Copperfield:

’And how’s your friend, sir?’ said Mr. Peggotty to me.

‘Steerforth?’ said I.

‘That’s the name!’ cried Mr. Peggotty, turning to Ham.

‘I knowed it was something in our way.’

‘You said it was Rudderford,’ observed Ham, laughing.

‘Well?’ retorted Mr. Peggotty. ‘And ye steer with a rudder,

don’t ye? It ain’t fur off. How is he, sir?’31

Corney, the name of the woman whom Mr Bumble courts and marries in Oliver Twist, was also the name of a glover and hosier at 178 Oxford Street, and there was a Mrs Malie commemorated in the local churchyard, whose name may have served for the kindly woman upon whose doorstep Oliver collapses.32 This is not to say that Dickens did not utilize other sources for names: he mentions the trade and street directories of London in several of his novels, and in the surviving ‘Memorandum Book’, Dickens noted the source of one of the lists he quarried, it was derived from the Privy Council Education Lists. Local street names crop up, too: Mr Micawber in David Copperfield adopts the name Mortimer when he is sued for debt, there’s Newman used as a first name for Newman Noggs, Charlotte in the undertaker’s in Oliver Twist, and sweet Betsey Ogle, perhaps from Ogle Street and Ogle Mews, at the back of the pub opposite the Workhouse, as well as the working of the eyes.

In his later essay of 1853, ‘Where We Stopped Growing’, Dickens tells the story of the White Woman of Berners Street, who has often been taken for the original of Miss Havisham in Great Expectations.

Another very different person who stopped our growth, we associate with Berners Street, Oxford Street; whether she was constantly on parade in that street only, or was ever to be seen elsewhere, we are unable to say. The White Woman is her name. She is dressed entirely in white, with a ghastly white plaiting round her head and face, inside her white bonnet. She even carries (we hope) a white umbrella. With white boots, we know she picks her way through the winter dirt. She is a conceited old creature, cold and formal in manner, and evidently went simpering mad on personal grounds alone—no doubt because a wealthy Quaker wouldn’t marry her. This is her bridal dress. She is always walking up here, on her way to church to marry the false Quaker. We observe in her mincing step and fishy eye that she intends to lead him a sharp life. We stopped growing when we got at the conclusion that the Quaker had had a happy escape of the White Woman.33

The essay is significant for this book, because in it we find Dickens admitting in 1853 to a childhood/youth association with the part of London at which we have been looking closely, although he is ‘unable to say’ if the White Woman was ever seen further north, in Norfolk Street for instance. He passes rather dramatically from past to present tense, and from Berners Street to ‘here’, as if he still lived in the near vicinity. Is Dickens saying that he had seen this woman pass up Norfolk Street, or possibly reach Devonshire Terrace? His arch prose, especially the ‘we hope’ in brackets, and the ‘no doubt’, lead one to think this is more of a tale he is enjoying in the telling, or a knowing elaboration of a local urban legend, than a witnessed reality. The curiosity of this story is compounded by two others, from different sources. Neither concerns Berners Street. The first is from nearby Oxford Street itself, and not in Dickens’s time:

Amid all its bustle and business, Oxford Street has nevertheless had a touch of ‘the romantic,’ if a peculiar eccentricity, brought about by disappointment in love affairs, can be called a romance. At all events, we read how a certain Miss Mary Lucrine, a maiden of small fortune, who resided in this street, and who died in 1778, having met with a disappointment in matrimony in early life, vowed that she would ‘never see the light of the sun!’ Accordingly the windows of her apartments were closely shut up for years, and she kept her resolution to her dying day.34

The Victorian book from which this account came provides no source for its information, so if we accept the date it offers we must conclude either that there were two such disappointed women in adjoining streets, and that one stayed indoors in the eighteenth century and the other walked out when Dickens was growing, or, that both stories attach to the same person.

The third tale is the account of an inquest of a real woman, a ‘wealthy and eccentric lady’, discovered by the Dickens scholar Harry Stone.35 Her death was reported in a news item Dickens himself published in a news supplement to Household Words in 1850 (‘Where We Stopped Growing’ appeared in 1853, Great Expectations in 1860). She had been badly traumatized twice as a young woman: first, her father was robbed and murdered in Regent’s Park; then, she had lost her reason when her mother rejected her suitor, and he blew his brains out while sitting beside her on the sofa. This lady lived as a recluse in Marylebone, three blocks west of Dickens’s home at Devonshire Terrace. She never went out, and dressed in white. How Dickens came to know of her story we are not told; she does not come up on database searches of other contemporary newspapers, but she certainly was a real person as she appears as Miss Joachim, 27 York Buildings, New Road, in the 1846 Kelly’s Post Office Directory.

The Dickens scholar Harry Stone has also uncovered a wonderful character based on the White Woman of Berners Street called Miss Mildew, of much the same ilk, who was played in drag onstage in 1831 at the Adelphi by Dickens’s favourite actor, Charles Mathews. There’s a good chance Dickens saw the performance, because he went anywhere to see Mathews, and in April 1831 he was freelancing and possibly living in the vicinity of the Strand, having just left Norfolk Street. Stone makes a splendid argument for Dickens’s weaving of Miss Havisham from the White Woman, Miss Joachim, and Miss Mildew.

Miss Mildew visits somewhere called the Great Expectoration Office to seek an expected fortune, which never arrives, which suggests she may have been a model for Dickens’s character Miss Flite in Bleak House (1852–3). The office Miss Mildew visits, and the one Miss Flite visits in the Chancery Court bear an affinity to both the Circumlocution Office (in Little Dorrit, 1855–7) and the Legal Loophole Office in one of Jack Fairburn’s Quizzical Gazettes.

The interweaving of story and locality is curious, made still more so by the added finding that the extinct peerage of Haversham was associated with two old houses on different sides of Soho Square, and that a livery stable in Newman Street was run by a man called George Habbijam, an unusual old English name that would have appealed to Dickens, especially in Mrs Gamp mode.36

Livery stables usually occupied mews premises, behind main streets, and were often accessible only through arches through street premises. Very often the interior walls of these arches featured large signboards with the names of the stable keepers or the tradesmen occupying the mews. I imagine Goodge and Marney had just such a sign in Berners Mews, Habbijam too, in his access-way to Newman Yard, behind Newman Street. And I wonder if Dickens was familiar with the sign of Bardell, another local livery stable keeper in Gresse Street, just off Percy Street?37

Several of the Sketches, it seems to me, resonate with the possibility of deriving from experiences in Norfolk Street and its vicinity, such as Dickens’s careful observations concerning the life-cycles of shops. Norfolk Street was full of shops, and we know that Dickens has seen their alteration between the two periods in which the family lived there, perhaps while they were there, and afterwards. There are, for example, a couple of shops in Norfolk Street which over time were divided into half-shops, which is something he describes; and of course he lived right next door to a broker, which is the subject of another Sketch.

Most particularly, I sense that the first appearance of Sam Weller in Pickwick—in which he makes philosophical observations on the relationship between the personality of the footwear he is called upon to deal with as the ‘Boots’ of an inn, and the individual character of their unseen owners—owes something to Dan Weller, the shoemaker/ mender across from Mr Dodd’s, especially as there was a public house named the Marquis of Granby in nearby Percy Street.38

Another important shop on Mr Weller’s side of the street was the pawnbroker. John Cordy Baxter’s shop occupied the top corner of Norfolk Street (at the junction with Union Street) diagonally across from Mr Dodd’s house. Mr Baxter’s was a busy establishment. His premises consisted of two shops, providing storage space for all the pledges, and housing for his own family and several assistants. Dickens had experience of pawnbrokers in his childhood: Forster mentions him having to pawn family belongings from the house in Gower Street, before the family went into the Marshalsea. To be made forcibly to let go of familiar things one is fond of is painful, and the fear of never being able to redeem them must hurt, too, along with the idea that someone acquiring them for their money value would have no conception of their deeper meaning, would not see their real character, would not recognize their biography. Dickens invests life in objects, recognizes their human echoes, resonances, meanings, to an extraordinary degree, and in his early Sketch, ‘The Pawnbroker’s Shop’, it is clear that he pities the poverty that brings people to the pawnshop, and recognizes the memories and meanings special objects can hold, and respects the understandable reluctance to part with them. The voice is that of an observer, but one who sorrows and understands.

Just after the child is born in the first chapter of Oliver Twist, Dickens describes the power of the old calico workhouse dress to transform the naked newborn infant from the multi-potent child into ‘the orphan of a workhouse’. He uses the imagery of pawnbroking to explain how the clothes work their effect: ‘he was badged and ticketed, and fell into his place at once’. Pawnbrokers’ storerooms are complex filing systems which allow for the swift disposal and retrieval of objects. In a pawnbroker’s shop every item deposited is ticketed, and according to Dickens’s own description, often land on the floor before being taken to the storeroom, and appropriately deposited on labelled shelves.39 This ties up with Dickens’s strikingly memorable use of similar imagery when he described his own creative process: ‘I never commit thoughts to paper until I am obliged to write, being better able to keep them in regular order, on different shelves of my brain, ready ticketed and labelled, to be brought out when I want them.’40

Objects taken in by a pawnbroker are ‘pledges’, a word that has the old biblical meaning of a solemn promise or something given as a guarantee of good faith, and with the sentiment associated with love-tokens (and indeed children) being ‘pledges’ of love. Of course a baby swaddled up does look a bit like a small parcel—one can see the physical association, too. The language of pledging is very prominent in Oliver Twist—one of the chapters is entitled ‘The time comes for Nancy to redeem her pledge to Rose’, and in addition to Nancy several characters—Noah Claypole (ironically), the Doctor, and Harry Maylie all pledge themselves in one way or another. Here a biblical word is also used in pawnbroking, and in both places it is also associated with the notion of redemption. This is not just a literary conceit: Dickens employs the language of pledging in his own voice, in his own life, especially in the early letters: in conjunction with assorted serious commitments to write, to publish, to get away to see Catherine, not to write for Bentley during an altercation, and to give his word; he even pledges his ‘veracity’.

As a boy Dickens had evidently visited one pawnbroker’s shop frequently enough, according to Forster, to develop a good relationship with one of the staff:

a good deal of notice was here taken of him by the pawnbroker, or by his principal clerk who officiated behind the counter, and who, while making out the duplicate, liked of all things to hear the lad conjugate a Latin verb and translate or decline his musa and dominus. Everything to this accompaniment went gradually.41

This particular pawnbroker would presumably not have been in Mr Baxter’s shop, as this story dates to about 1822/3 when the family was living some distance away. The experience seems to have been important for Dickens: not only did he tell Forster about it, but the relationship with the shop man seems to have humanized for him the sad business of losing belongings, and perhaps softened the shame of needing to enter such a place, and also allowed him to see that a shopkeeper might be educated enough to know some Latin.

In his Sketch ‘The Pawnbroker’s Shop’ Dickens places the shop in Drury Lane, but as we know, he likes to cover his tracks, and he may have been making a nod to Hogarth when he did so. The essay was published in June 1835, so he had been researching the subject, observing carefully, and perhaps making notes the year before he started Oliver Twist. It may be that he knew more about pawnbroking than Forster has told us: the business of it looms very large in Martin Chuzzlewit, and the pawnbroker’s shop man carries the same first name as David Copperfield. Cruikshank’s image for Dickens’s Sketch is an interesting view taken from behind the counter, inside the shop, which certainly feels true to the spirit of the Sketch. Dickens’s interest in the backstage stories of pawnbroking lasted all his life: the very last entry he ever made in his little book of memoranda not long before his death in 1870 was: ‘The pawnbroker’s account of it?’42

The assistants in the Drury Lane pawnshop of Dickens’s early Sketch are described as treating customers without much respect: deliberately filling in duplicates slowly, talking between themselves, and making them wait. But the entry of the boss, in a grey dressing gown, is a breath of different air: he has an authoritative manner, firm but humane: taking charge to refuse money to a violent drunkard, telling him to send his wife to receive the money instead.

I like to think this might be a sketch of Mr Baxter, the pawnbroker in Norfolk Street, partly because it would be good to get a glimpse of him, and partly because he was an interesting man. I have found him on one occasion donating the large sum of 30 guineas to a special appeal fund to open two new wards at the Middlesex Hospital, an amount greater even than that given by the aristocratic patroness of the appeal, the Duchess of Buccleuch.43 His name appears, too, alongside that of the artist John Constable, who lived nearby in Charlotte Street, on a petition to Parliament in 1831 in support of ‘Assisting the Cause of Reform’.44 So it is not possible to perceive Baxter as a mere money-grasper of a pawnbroker: he was an altogether more complex, thoughtful, and humane man.

Dickens’s portrayals of pawnbroking as a trade are mixed, for although he knew that money obtained on household goods often went on drink, he also understood the pathos of the need to raise pennies on household belongings, especially before weekly paid wages arrived at the end of the week. He knew that while pawnbrokers exacted high rates of interest and ultimately often took as forfeit precious goods that could not be redeemed, they also performed an important doorstep banking service for the poor, and that sometimes the money lent could provide a lifeline.45 In 1837, while Oliver Twist was still appearing in monthly parts in Bentley’s Miscellany, Dickens (the Editor of the journal) published an anonymous poem which expressed this ambivalence, under the generic term for a pawnshop, ‘My Uncle’:

… Above his door

Invitingly were hung three golden balls,

FIGURE 37. A pawnbroker’s shop interior, said to have been in Drury Lane. The view is taken from a privileged position behind the counter. In the open public part of the shop on the left, an assistant publicly assesses the value of a garment. The private boxes were for those seeking greater privacy in their transactions. Recent ticketed goods for warehousing are seen on the floor. The shop door shows that like Mr Baxter’s, this pawnbroker’s was situated on a corner. If this image was reversed in printing, the position of the private entrance and the shop window would match Baxter’s shop too. Etched by George Cruikshank for Sketches by Boz, 1836.

As if to say, ‘Who pennyless would go?’

Here is a banking-house, whence every man

Who has an article to leave behind,

May draw for cash, nor fear his cheque unpaid.

Ah me! Full many an ungrateful wight

In this same store, without a sigh or tear,

Parted his bosom friend, altho’ he knew

That friend must dwell among the unredeemed.46

Mr Baxter has been examined with attention here, because I have a hunch that his shop may be central to Oliver Twist, in which the plot hinges upon the fate of a locket, secretly taken from the body of Oliver’s mother after her death in childbirth. This locket is the key to Oliver’s real identity, and its fate is fundamental to the entire story. It is described as a small gold locket, engraved with his mother’s name ‘Agnes’, with space left for a surname, and a date less than a year before Oliver was born. It contained two locks of hair and a plain gold wedding ring. In the book, Oliver’s malevolent half-brother Monks gets hold of the locket from the workhouse Matron, and drops it through a trap door into a rushing millstream, thinking he has destroyed the evidence of Oliver’s parentage.

But Dickens allows Oliver’s champion, Mr Brownlow, to establish the chain of evidence without this precious object itself. Two very elderly women from the workhouse, who are brought before Monks and the Matron in chapter 51, report that they had overheard the conversation between the workhouse Matron and the dying pauper nurse, Old Sally, who long before had nursed Oliver’s mother, laid out her body, and purloined the locket. These elderly women announce that they had seen the Matron take the pawn ticket from the dead woman’s closed hand, and that they had watched her go to the pawnbroker’s the next day. Their testimony indicates that a pawnbroker’s shop was in very close proximity to, indeed visible from, the workhouse. So it may be highly important that Mr Baxter’s shop stood diagonally opposite from the Cleveland Street Workhouse, and was also clearly visible from Dickens’s front windows of No. 10 Norfolk Street. Mr Baxter’s shop on the corner at 15 Norfolk Street is gone, but from the street corner outside his shop door, one can still look north up Cleveland Street and see the Workhouse, and southdown Norfolk Street to Dickens’s family home.

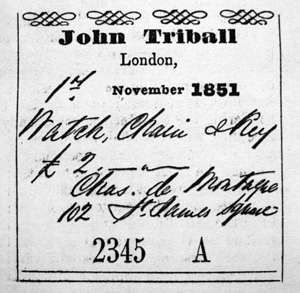

FIGURE 38. A nineteenth-century pawn ticket. Illustration to an essay entitled ‘My Uncle’ by Henry Wills (edited/retouched by Dickens himself), which originally appeared in Household Words in 1851. The fate of such a ticket is crucial to the plot of Oliver Twist. Reproduced in Wills’s Old Leaves. New York, Harper, 1860.

There is a wonderful moment in Oliver Twist, after the old women have given their evidence about the origin and fate of the locket, when Mr Brownlow’s friend Grimwig asks the discomfited Mr and Mrs Bumble and Monks: ‘Would you like to see the pawnbroker himself?’—and motions towards the door. It is almost as if that eminence grise, John Cordy Baxter, was waiting in the hall.47

FIGURE 39. Sightlines between the Workhouse and Mr Baxter’s corner (15–16 Norfolk Street) and Dickens’s home. No. 11 Cleveland Street stands obliquely above the northern boundary of the Workhouse site.

In the Pickwick Papers, Sam Weller tells Mr Pickwick that he was originally apprenticed to a carrier. Curiously, the trade list of public carriers in the London Directory yields the following Dickensian-sounding names: Sikes, Sykes, Sugden, Tubbs, Siggs, Ruggles, Noah, Tugwell, Medlock, Bundle, Catchpole, and Diggens.48 But one of the key figures in Oliver Twist probably did not come from this list. Perhaps the most telling instance of Dickens’s use of a name from a local shop board, and one which provides evidence of an unquestionable association between Oliver Twist and the Cleveland Street Workhouse, is that of the shopkeeper at No. 11 Cleveland Street. He was an oilman, who sold tallow and oil for lamps and perhaps for paints, and whose first proud appearance in the London Commercial Directory of 1836 coincided with that of Dickens himself: ‘Dickens, Charles—Reporter for the Morning Chronicle’. This man’s shop faced the Workhouse, and his name was Mr William Sykes.49

The variant spelling of his surname may have appealed to Dickens for the book because it served to deflect identity from the shopkeeper, and perhaps protected Dickens himself (useful if the oilman was as malevolent in appearance as the real Bill Sikes!); and possibly too from the irony that it was shared with a very well-heeled firm of City bankers, at the Mansion House.50

In 1818 the shop at No. 11 Cleveland Street had been occupied by a different wax and tallow-chandler called Biddle, so the name is not a childhood memory. Sykes was a relatively new arrival, as he was not the ratepayer in 1828, so his shop board might have been spruce and bright, attracting attention to itself.51 Further research will be necessary to try to pin down when Bill Sykes actually arrived in Cleveland Street. But he was certainly there in 1836–7 while Dickens was planning and writing Oliver Twist.52

FIGURE 40. Cast pewter regulation button from the Strand Union Work-house. Manufactured for the Guardians of the Strand Poor Law Union by W. H. Norton of 249 Strand in the mid-nineteenth century. Found in the 1980s on the foreshore of the Thames.