On 10 July 1820 the English abolitionist Thomas Clarkson wrote a thirty-one-page letter to the King of Haiti, Henry Christophe, in which he provided a detailed account of his recent trip to France at the behest of the King. He had gone there, in the words of his mission statement, to discover ‘the bases upon which a solid and durable peace may be built’ between Haiti and its former colonial master.1 Clarkson’s letter to the King was one of dozens that had been exchanged between the two men since the initiation of their correspondence in 1815. Over the course of the intervening five years, Clarkson had become a veritable ‘good-will ambassador for Christophe’ (Griggs, 71), promoting his cause in Britain and singing his praises to foreign leaders such as the Emperor of Russia, Alexander I.2 By 1820, as the mission to Paris attests, this ‘ambassadorial’ status had gained an official dimension, the Englishman having been ‘authorized’ to make overtures to the French government on Christophe’s behalf, ‘leaving to the discretion of Mr. Thomas Clarkson the choice of the means and avenue of approach’ (Griggs and Prator, 175). Given that the King’s ‘sine qua non condition’ for any negotiations with the ‘King of France and Navarre’ was that he ‘recognize Haiti… as a free, sovereign, and independent state; that he deal with Haiti as such; and that on his own behalf and in the name of his heirs and successors he renounce all claims to political, property, and territorial rights over Haiti or any part thereof’, and that Christophe had ruled out from the start ‘any indemnification of the ex-colonists’ (175), Clarkson and the influential abolitionists such as William Wilberforce and James Stephen with whom he consulted in the days leading up to his trip to France recognized the ‘hopeless’ nature of the treaty that Christophe was pursuing. Clarkson thus informed the King, in a letter of 28 April written days before he left for France, that he had chosen to travel there ‘not as a public agent but in his own individual capacity’, with the goal of ascertaining ‘the particular disposition and state of France as they relate to Hayti’ (198). Notwithstanding his realistic assessment of the situation, Clarkson ended this letter with the buoyant assertion that ‘I shall go as a private individual but shall take my Diplomatic Papers with me in case of an unexpected turn’ (199).

Christophe and Clarkson’s transatlantic correspondence brings together two figures of massive importance in the history of slavery and its abolition. On the one hand, Clarkson, ‘arguably the great Founding Father of all abolitionism’ (Davis, 2006, 189), a man who ‘made antislavery causes his purpose in life’ (C. Brown, 436), from the publication of his first Essay on Slavery in 1786 and the founding of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade the following year, to the successful abolition of the slave trade (1807) and slavery (1833) in the British colonies, and on through to his opening address at the 1840 World Antislavery Convention, which he chaired with ‘the zeal of a venerable old man in the cause of freedom and our race’, as the African American abolitionist Alexander Crummell put it in his 1846 eulogy for this ‘illustrious friend of Africa and her children’ (31, 32). On the other hand, Christophe, the revolutionary hero, one of Toussaint Louverture’s closest and most trusted associates from 1794 onward, second-in-command to the first leader of independent Haiti, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, and, upon the latter’s death in 1806, President and (as of 1811) King of the northern half of Haiti, a man whose ‘wide-ranging and ambitious efforts aimed at creating a sustainable postemancipation state deserve more attention than historians have usually given them’ (Dubois, 2012, 64).3 However, for our purposes, Clarkson’s lengthy letter of 10 July is primarily of interest not because of its pairing of heroic figures who have established a name for themselves in the annals of world history, nor for its exhaustive assessment of Franco-Haitian relations, but because of the prominent role played in its concluding pages by a third, far lesser known figure, whose media(tory) role emerges as a subject of intensive commentary—and, as we will see, projection—on Clarkson’s part. That third party is, of course, Baron de Vastey, Christophe’s chief publicist (and, by this point, Chancellor of the Realm), who had over the past several years gained a reputation in Britain as Haiti’s ‘most distinguished political writer’, someone whose work ‘abounds with deep and original views’, to quote an 1820 assessment of his Réflexions politiques (‘History’, 73). Clarkson’s repeated appeals to Vastey in his letter provide the central focus for this opening section of my Introduction, because they allow me to elaborate on the general portrait of Vastey as a scribe that I sketched out in my Preface: that is to say, as a writer whose subject-position can only with the greatest of difficulty be conceived of apart from the sovereign power it serves. The extended treatment offered here of Clarkson’s letter is further justified by the fact that the published version of it has been so extensively pruned that the obsessiveness of the English abolitionist’s appeals to Vastey cannot be gauged without recourse to the original document.4

Clarkson’s 1820 letter concludes with a list of eight things the King ought to do should he prefer to make no treaty with France and ‘abide by the consequences’. Six pages are devoted to expanding upon the penultimate of Clarkson’s eight suggestions, namely: ‘I would recommend it to your Majesty to avail yourself of the able and respectable talents of the Baron de Vastey by asking him to undertake a small literary work’ (175v–176r). Clarkson begins by noting that during a trip to France five years before he had ‘had the mortification to hear your Majesty’s Government ridiculed and your private character stigmatized’. During the just-completed journey, by contrast, he had ‘the satisfaction of observing that a considerable change had taken place in the public opinion on that subject, but particularly as to your character as an Individual. You are now no longer the cruel monster, which the ex-colonists had represented you to be. This happy change’, he continues, ‘has been effected by your Majesty’s friends who have circulated (both by means of books and conversation) many facts relative to your political regulations, of which almost all had been before ignorant’. The purpose of the ‘small literary work’ to be undertaken by Vastey (with whom Clarkson had, as we will see, entered into personal correspondence the year before) would thus be to give further publicity to the regime’s aims and accomplishments, so that ‘the French Nation should become better acquainted with your Majesty’s true character, or that they should be still more enlightened on this subject’, in order that it ‘should rise in estimation till those prejudices are finally done away, which have hitherto supposed people of colour to be incapable either of knowledge or virtue’ (176r). Placing the same trust in Vastey’s ability to make his readers ‘see’ and ‘recognize’ Christophe in a proper light as did the regime itself,5 Clarkson’s then-and-now narrative invokes a faith in what we might call (transcending) representation that is central to abolitionist discourse, which through the power of ‘books and conversation’ aims to effect a quasi-ontological transformation (‘You are no longer…’) of the misrepresented object (‘slave’, ‘negro’…) of its humanitarian rescue mission. In this case, Christophe is transformed from the monster he is represented as being and the prejudices this trope engenders to the real person of colour he is, a man in possession of a ‘true character’ that can be revealed by means of facts and their circulation in the public sphere. In the case of Christophe, of course, the binary terms of this ‘enlightenment’ project cannot but seem, at best, highly problematic to us, given the epistemological impasse in which contemporaries of Clarkson,6 no less than historians of today,7 found and find themselves when trying to assess the ‘true character’ of Christophe and of those, such as Vastey, who served under him.

These broader questions of representation form an inescapable backdrop to any (re)assessment of the seemingly disheartening realities of post/revolutionary Haiti.8 Leaving such questions aside for the moment, however, we can return to the details of Clarkson’s letter, which quickly shifts attention away from the problem of representation to the enactment of it, with some very specific suggestions for the form that Vastey’s ‘small literary work’ should take:

You may be assured that the nearer your Majesty, and the Haytian Government, and the Haytian People are considered to approach to a level with the enlightened Princes, Governments, and Nations of Europe, the less obstruction you will find to being nationalized, or to being received among the acknowledged Governments of the world. I would advise therefore, that the Baron de Vastey should directly compose a little work of about 40 or 50 pages only for this purpose; for the shorter the work the better, provided it comprehended all the necessary facts. The following are my ideas upon the subject.

The work might be entitled ‘A few observations on the Government of the North Western part of Hayti from its infancy to the present time’. The Baron would probably find a better title than this before he finished it.

The Baron might begin by stating, that so many calumnies had been spread relative to this Government, that it seemed necessary to give to the European world some authentic documents to refute them. (176r–v)

What is remarkable about these opening suggestions regarding the best way for Christophe, his government, and his people, to become ‘nationalized’ is simply the level of detail to which Clarkson descends. Providing Vastey, through the mediating figure of the King, with exact instructions regarding the page length of the ‘little work’, its title, and how it ought to begin, Clarkson is practically dictating the terms of composition, while at the same time acknowledging the possibility that these terms might be improved upon by his Haitian counterpart, notably in relation to the title, with its overly precise geographical specifications and its benignly infantilizing vision of the Christophean regime.

Clarkson’s abolitionist dictation, once started, proves hard to stop. After suggesting how A few observations ought to begin, he then proceeds, in the next five paragraphs (176v–178r), to map out various points that Vastey should make in order to clinch the argument Clarkson wants him to pursue. This argument requires him to ‘paint in true colours the disorganized state of society as it was’ when Christophe came to power (176v), and contrast it with ‘the present state of the inhabitants of Hayti’ by enumerating the various reforms undertaken since that time, such as ‘the number of Professors you had introduced into your Dominions and of which sort; the Schools you had formed by degrees, and in what places, and in short every act done by your Majesty to improve the condition of your subjects, whether in Justice, Agriculture, the Arts, Literature, or Religion’ (177r). One need only cite the first few words of the opening sentence of each of these paragraphs to get a sense of the well marked path that Vastey is being called upon to follow when describing the regime’s passage from a state of infancy to its present (progressing toward) enlightened state: ‘He might then describe the political state of Hayti, as it was when your Majesty was proclaimed King…’; ‘He should then proceed to state that…’; ‘The Baron would have here a fine opportunity of observing that…’; ‘The Baron should then begin with…’; ‘After having done this he should say…’

In the last of these prescriptive paragraphs, Clarkson is particularly concerned, given the common sentiment among those with whom he consulted in France that Christophe’s ‘was no Government, it was a mere Despotism’ (177v), that stress be laid on the King’s efforts at educating his people and on his willingness ‘to extend political privileges by degrees as you found them fit for such a blessing’ (178r). When he himself stressed this point, Clarkson notes, it ‘made a considerable impression on the minds of those, with whom I conversed, in your Majesty’s favour. I should advise, therefore’, he continues, ‘that the Baron de Vastey should say a few words on this subject in the little work now mentioned’. Vastey, Clarkson suggests, ‘might state that the system of education which your Majesty was giving to your subjects was intended as a foundation on which to build with safety a political constitution which should embrace the rational liberty and happiness of all your people. I am sure’, he concludes, ‘that an avowal, like this, would please many of your Majesty’s friends and disarm many of your enemies’ (178r), revealingly, if doubtless unintentionally, drawing attention to the fine line between truth and persuasion with his pragmatic appeal to pleasing friends and disarming enemies.

As if that detailed outline of the book’s structure were somehow not enough, Clarkson then immediately circles back to the big picture, offering new strictures on its overall form and content, as well as an explicit rationale for the choice of Vastey as the work’s author:

Permit me to say a few words more concerning this little work, which, though little, I consider to be of great importance.

In the first place it must be written by the Baron de Vastey. No one of your Majesty’s friends in England could write it, because all the documents are in Hayti; and no person could write it, who had not witnessed the whole process of the improvement which has taken place in your Dominions, or who had not seen the wonderful change, which has been produced from the beginning of your Majesty’s reign to the present time.

Secondly, it should contain a plain statement of facts, without any extravagant embellishment from the flowery powers of oratory.

Thirdly, it should be written in the most modest manner, and with the greatest temperance.

Fourthly, nothing should be mentioned in it concerning Protestantism or any intended change of religion. Nothing of a political nature should appear in it. No reflection should be made upon France: indeed it would be better not to mention France at all, except in a respectful manner. (178r–v)

Clarkson begins by insisting upon Vastey’s privileged status as a witness, a native mediator possessed of a first-hand knowledge/vision of Christophe’s Haiti and who is thus in a position to make his readers see ‘the wonderful change’ between its infancy and its present condition in a way that Clarkson cannot—even though the English abolitionist has devoted so many pages to showing the Haitian witness what this change is and how best to represent it!

Clarkson’s final three points offer an implicit reading of (and in the case of the last two, warning about) Vastey’s established textual practice, and can thus be usefully read in relation to his work as a whole, and to Le système colonial dévoilé in particular. The first directive, in which Clarkson advises Vastey (via Christophe) to stick to ‘a plain statement of facts’ and to avoid ‘the flowery powers of oratory’, corresponds very well to Vastey’s own assertions in Colonial System regarding the unsuitability of rhetorical flourishes and stylistic embellishments when describing the horrors of slavery and the consequent need to restrict oneself to ‘reporting the facts’ (1814b, 40). If an avoidance of flowery embellishment characterizes all of Vastey’s work, the same cannot be said for his relation to intemperate language: one has only to read the call to arms with which Colonial System concludes, with its apocalyptic vision of sharpened Haitian bayonets and pierced French bellies (96), to get a sense of the distance that Vastey had to come (or would have to come) in order to meet the modest demands of Clarkson’s abolitionist discourse. The strictures regarding any discussion of Protestantism aside,9 the final directive offers even more of a challenge to Vastey in its insistence that nothing of a ‘political nature’ appear in the projected book (as if any discussion of Haiti could be divorced from politics), and its emphasis on the need to omit any but the most respectful references to France: as Clarkson well knew, France was the Gordian knot that Vastey’s books never ceased trying to cut, with a discursive violence that, while certainly present in Colonial System (the last sentence of which ends with a reference to ‘the myriad crimes of the French in Haiti’ (97)), seems, if anything, to have gained in strength over the course of his career as Christophe’s publicist.

After these stipulations, Clarkson then concludes his account of A few observations with one last paragraph in which he offers practical advice regarding how to go about publishing and circulating it.10 What I hope has emerged from my purposely detailed rendering of Clarkson’s obsessively precise instructions is a clear sense of the institutional framework within which Vastey’s oeuvre was produced—or, in other words, a clear sense of the scribal conditions that (as argued in the Preface) must be the starting point for any appraisal of him as a writer. At the side of power, rather than to the side of men of state such as Christophe (see Bongie, 2008, 32–33), the scribe, in transmitting his message, is subject to all sorts of stifling compromises and complicities; his acts of mediation are subject to a painfully evident lack of room for manoeuvre. What sort of ‘literary work’ can possibly emerge from these scribal conditions? That is the difficult question that Vastey’s publications pose any reader today, and which makes them a challenge to read in relation to other Afro-diasporic writing in which ‘the structural dependence that subjects literary practices to political authority’ is altogether less obvious (Casanova, 199), or even, we might like to imagine, entirely absent.11

What is especially interesting about the scribal dynamics on display in Clarkson’s letter is that the double labour Vastey is called upon to perform—working on behalf of the ‘nationalization’ of Christophe’s regime as well as serving the global needs of the abolitionist movement— creates a triangulated relation, which complicates the standard binary pairing of sovereign and scribe. Of course, that pairing, and the strict division of labour it implies, was never as uncomplicated as one might imagine: Deborah Jenson has argued, for instance, that ‘the first leaders of the blacks in Haiti’, Toussaint Louverture and Jean-Jacques Dessalines, cannot be read simply in terms of a power/writing binary of the sort more readily attributed to the ‘formalized’ scribal relation between Christophe and Vastey: the documents associated with these first leaders, Jenson maintains, must also be read as, in part, produced by them; they ‘exemplify, in themselves, both political power and the most tenuous but determined approaches to the magical sphere of literary and mediatic persuasion’ (6). If, at the dawn of the independence era, the mediatic work of Toussaint and Dessalines (partially) collapses the distinction between sovereign and scribe, some fifteen years later the efforts of the post/revolutionary state at making itself heard and gaining recognition for itself can be said, on the evidence of Clarkson’s letter, to have generated the reverse scenario, an expansion in the number of players and a consequent blurring of the lines between them. Who is the sovereign and who is the scribe here in this triangulated relation?

Most obviously, of course, Christophe remains the sovereign, at the head of the triangle, with his ‘agent’ Clarkson and his secretary Vastey occupying the scribal base (along with any number of other Christophean scribes such as Baron de Dupuy or Chevalier de Prézeau). And yet the three-way relationship can also be read not so much as a triangle but as a chain of command extending from the metropolitan centre to the post/colonial periphery, given the fact that Clarkson is dictating the terms of the book to his addressee, Christophe, who will in turn pass them along to Vastey, who must take both authorities into account. This second reading nicely coincides with any suspicions we might have about the congruence between abolitionist and colonial discourse, but it scarcely takes into account the level of desire infusing Clarkson’s excessively detailed and repetitive advice; the projected book requires an all too evident projection of himself onto Vastey, the man who has witnessed that which Clarkson can only longingly imagine. In a third reading, then, it is the lateral relation between the Haitian scribe and his English double that is of central importance, rather than the sovereign power that makes these relations possible.

The psychologically fraught nature of this lateral relation is clear enough: there is great potential for rivalry and envy (which can also extend, of course, in a vertical direction from the scribal base to the sovereign vertex). However, there is also the potential for new forms of collegiality, a conversation of equals in the republic of letters, engaging with one another on their own terms rather than those of the sovereign in whose shadow they serve. We get a sense of what this more ‘autonomous’ relation between the men might involve in the shards of their personal correspondence, which consists of two letters of Vastey’s to be found in Clarkson’s papers, most notably one dated 29 November 1819 that is of vital importance for any consideration of Vastey because it supplies us with so much of the scarce personal information we have concerning him (Griggs and Prator, 178–82; fols. 122–127).12

Accompanying this letter to Clarkson was a copy of Vastey’s recently published history of the Haitian Revolution and its aftermath, the 1819 Essai, along with a number of other unidentified works that, Vastey suggests, ‘will be useful to you in the course of your negotiations each time you wish to find arguments and review the facts’ (179). Rather than simply explain how the book will help Clarkson understand the Haitian Revolution and, especially, the post/revolutionary division of Haiti into the northern kingdom and the southern republic, Vastey prefaces that explanation with more personal comments bearing on his reasons for writing the Essai:

Exasperated at seeing in the journals of the South and in those of France, their faithful echoes, the calumnies which the enemies of Haiti and the King endlessly repeat concerning his government and his person, I decided to tell the truth in the matter [je me suis décidé à les réfuter]. This led me into the writing of a whole volume on the origin and cause of our civil dissensions. I was able to devote only two months to the composition of this work and furthermore I was ill most of the time, so you will undoubtedly find it full of imperfections. Though I did not have at my disposal enough time to do it properly, I nevertheless flatter myself that, with all its flaws, this book will cast a great deal of light on our wars. (178–79; 122v–123r)

As we saw in the preceding Biographical Sketch, this autobiographical commentary about the origins of Vastey’s book is accompanied, at the very end of the letter, by key facts regarding his own origins (his place and date of birth), as well as details about his wife and two daughters, and about his personal relation to the revolutionary leaders Toussaint and Dessalines (181–82).

In this ‘friendly interchange of confidences’ (181), we thus witness a twinned emphasis on text and self that goes well beyond the letter’s scribal purpose of preparing Clarkson for his diplomatic mission: we see (the possibility of) Vastey emerging as an author in his own right/write, speaking as someone who has gained enough, or almost enough, cultural capital to distinguish his work from the cause that it serves and to call it his own, to lay claim to it as something truly ‘literary’, in the particular sense according to which we now commonly understand the word—a historically uncommon understanding that clearly has yet to inform Clarkson’s (to us) puzzling identification of his (and Vastey’s) A few observations as a ‘small literary work’, and his various other references in the correspondence with Christophe to Vastey’s ‘literary labours’ (Griggs and Prator, 186).13 Speaking as Clarkson’s transatlantic confidant rather than Christophe’s secretary, Vastey seems here to be on the cusp, as it were, of author(iz)ing himself, of escaping the (to us) deathly confinement of his scribal role and speaking as a sovereign self, in an ‘authorial voice’ of the sort we have come to recognize and valorize, a voice ‘strongly associated with individual genius, solitary writing, and specifically authorial access to print culture’ ( Jenson, 5). It is this unshackling of Vastey from the scribal role to which he is so closely bound that is the ineluctable horizon for anyone hoping to salvage him for posterity, to reintroduce Vastey to a contemporary audience as a figure of more than purely historical interest, a figure of (literary) value. It is this very horizon which Aimé Césaire gestured toward at the end of La tragédie du roi Christophe, when he gave his theatricalized Vastey the final word, allowing him to speak, for the first time, in a language that is not direct and transparent, miraculously arming him, in a grandiloquent closing elegy for the dead Christophe, with an elevated form of speech reminiscent of nothing so much as the dense and hermetic language of Césaire’s own lyric poetry.14

Desirable as this horizon might have been for Vastey, and might still be (for us), it would remain, and remains, precisely that. An altogether more literal death awaited this scribe, who would never have the chance to write, and re-title, his (and Clarkson’s) A few observations much less the opportunity to assert his autonomy by not writing it. By the time the thirty-one-page letter arrived in Haiti, ‘Christophe was no longer alive, and as Clarkson remarks in his autobiography, “my labours for him and the people of Hayti were all in vain”’ (Griggs, 73). That August, Christophe suffered a paralytic stroke and his weakened condition ‘emboldened members of his regime who were increasingly unhappy with his rule, and within a few months, several officers organized a conspiracy’ (Dubois, 2012, 85). On 8 October, faced with open mutiny, unable because of his debilitated condition to lead a response against the conspirators, Christophe committed suicide. By the time Boyer and the southern army arrived in Cap-Henry on 22 October, seizing the opportunity to reunify the country (which was hardly the outcome desired by those northerners who rose up against the King with the purpose of supplanting him), Vastey had been dead for three or four days, summarily executed by the leaders of the revolt. As we saw in the Biographical Sketch, the details of Vastey’s execution, much less the exact reasons for it, will remain forever shrouded in doubt, but this brutal conclusion to the life of our Haitian scribe, not yet forty, is hardly surprising, given that he was the primary spokesperson for the Christophean regime, and someone increasingly central to the actual governing of the kingdom. Vastey died, while lesser scribes escaped to serve new masters, such as the former Comte de Rosiers, Juste Chanlatte, who made a smooth transition from one sovereign to the next, ‘glorifying the memory of the enemy [Pétion] of his defunct king, with the goal of toadying up to Boyer and his collaborators’ (H. Trouillot, 1962, 63–64).

In the words of historian David Geggus, Christophe’s downfall was ‘a double blow for the British abolitionists, effectively ending their direct links with Haiti and greatly undermining its propaganda value for the anti-slavery cause’ (1985, 126). Clarkson, ever (in the words of one of Vastey’s letters to him) ‘the sincere friend of humanity and the zealous champion of the unfortunate Africans and the Haitians, their descendants’ (Griggs and Prator, 136), did what he could to help out the exiled Queen and Christophe’s two daughters, ‘hospitably receiv[ing] them as house guests for nearly a year’ when they arrived in England in 1821 (Griggs, 79). On 16 December 1820, prompted by ‘some intelligence which I have this day received’, the other leading figure of the abolitionist movement in Britain, Wilberforce,15 who had himself been in communication with Christophe since 1814, having just learned of the coup and still unsure as to who had taken charge of the kingdom, directly petitioned ‘the head of the Haytian Government’, whoever he might be, on behalf of Vastey. ‘It is currently reported’, Wilberforce wrote, ‘that M. de Vastey has been imprisoned by the new Government of Hayti, and that it is intended to punish him capitally’.

I am utterly ignorant of the crimes of which M. de Vastey may have been guilty, and therefore it is not for me to presume to form any opinion on the punishment to be inflicted on him. But it cannot be wrong, nor can it, I trust, be in any degree likely to offend, if, taking, as I must ever do, a deep interest in all that concerns the character and fortunes of all the descendants of the African race, I feel desirous of enforcing on you the important truth, that the eyes of all the civilised world are anxiously directed towards you; and that the course which the Haytians shall pursue in their present critical circumstances, may tend powerfully to gladden or to depress the hearts of those who, like myself, have long been their partisans and advocates. (Wilberforce, 1840, 392)

Wilberforce’s main point is to ‘enforce’ the idea that any breach in the rule of law in Haiti will damage the public image of blacks the world over, confirming the prejudices of those who cite ‘the violence and cruelty with which they were disposed to act towards each other in those contentions which too commonly take place in political society’ as one of the ‘proofs of their inferiority’; hence, Wilberforce advises, ‘the importance of letting the principles of your proceedings be manifest to the world’, and of ‘let[ting] even guilty men enjoy the benefit of a fair and impartial trial’ (392–93). But the fact that his comments are made specifically on behalf of Vastey speaks volumes to the latter’s emerging reputation as someone whose value to the abolitionist cause could be conceived of apart from the institutional relation to Christophe upon which it had been founded, and interestingly anticipates the special emphasis in our own age of ‘humanitarian reason’ on the figure of the writer as particularly vulnerable to censorship and persecution.

Its cautious, supplicatory tone notwithstanding, Wilberforce’s letter— in its enforcement of truth and its appeal to the overseeing power of ‘the eyes of all the civilised world’ (a scopic power so far-reaching it would appear not to need the sort of mediation that Clarkson required of Vastey)— undoubtedly evinces the hierarchical dynamics that were an inescapable part of abolitionist discourse then, as well as the ‘tension between inequality and solidarity, between a relation of domination and a relation of assistance’ that is ‘constitutive of all humanitarian government’ in the present (Fassin, 3). The particular domination of British abolitionism in post/revolutionary Haiti had, however, as Geggus notes, come to an end with the death of Christophe: the new regime, obviously, was not in a position to take Wilberforce’s belated advice with regard to Vastey, and the Englishman’s broader offer of ‘all the assistance in my power’ (394) was a gift the new head of the Haitian government had no interest in accepting, given the frequency with which the reviled Christophe had received it in the past, and the longstanding Francophilic leanings of the rulers of the southern republic.

Vastey’s own repeated acceptance of this transatlantic gift, and his consequent entanglement in an abolitionist relation of domination and assistance, mirrors at the international level his scribal relation to power at the national level, while also offering, as we saw, the unrealized possibility of somehow transcending it and gaining entry to the world republic of letters. To examine Vastey’s scribal links to Clarkson in particular, and British abolitionism in general, as I have done in this opening section of the Introduction, is inevitably to confront the problem of what it means for the colonized (or formerly colonized) subject to be in this particular relation to abolitionism and its humanitarian discourse: should that relation be a source of concern or of (muted) optimism? Should we take a moral(izing) distance from it, by exposing what Marcus Wood has, glossing Fanon, dismissed as ‘the benign lie of the emancipation moment’ (2010, 29); by emphasizing the ‘complicated and compromised history that in reality surrounded the reluctant and flawed British approach to emancipation’ (262); by deploring ‘the controlling mechanisms of emancipation propaganda’ (160), as well as the starring role played in (the memory of) that mythic enterprise by ‘moral “big daddies”’ such as Clarkson and Wilberforce (16)? Or—as Paul Gilroy has recently argued in his advocacy of modes of ‘heteropathic identification’ that might (despite all sorts of institutional complications and compromises) ‘open up possibilities for change achieved through social and political mobilisation’ grounded in ‘the idea of universal humanity’ (66, 65, 72)—are such blanket critiques of abolitionist assistance (and, by extension, all forms of humanitarian government) perversely deaf to the promise of abolitionism and of other kindred appeals ‘against racism and injustice in humanity’s name’ that, for Gilroy, can and must be made in the spirit of ‘the new humanism’ argued for by Fanon (69)? (A very different Fanon from the one invoked by Wood in his critique of the ‘moral pollution and aesthetic contamination’ generated by the myth of the ‘gift of freedom’…16)

Notwithstanding his scribal commitment to ‘Misters Clarkson, Wilberforce, Stephen, and in general all the virtuous philanthropists of the great and magnanimous British nation, who have devoted their talents and their labours, their days and their nights, for the happiness and perfection of the human species’ (1816c, 56), Vastey was well aware of the possible limits of their (and his own) position, as we can see from a toast that he delivered at the Café des étrangers in Cap-Henry on 24 August 1816, during a banquet given for prominent Haitians by the town’s foreign merchants as part of a week-long celebration of the Queen’s birthday.17 Lifting his glass, Vastey drank, ‘To the gratitude that we owe the virtuous Philanthropists who have defended our Cause with as much ardour as disinterestedness; if their Wishes and their Efforts prove unavailing, then let us make use of our Swords, to cleave the Body of the Enemies of Humanity, and preserve the Rights that we derive from God, Nature, and Justice!’ (1816d, 42) Vastey’s double-edged toast reckons with the possibility that philanthropy, and the humanitarian assistance it offers, might prove unavailing (impuissant), and that it might thus need to be supplemented by another, more powerful and uncompromising response to racism and injustice, one that models itself, intemperately, upon the memory of the Haitian Revolution and its world-historical struggle between the friends and enemies of universal emancipation.

In its doubled appeal to the seemingly very different imperatives of philanthropic virtue and revolutionary violence, of institutional patience and emancipatory action, Vastey’s toast perfectly exemplifies a post/revolutionary sensibility, in which the presence of the revolutionary past continues to haunt a dramatically transformed present and its visions of the future. So perfectly, indeed, that we could readily dismiss the toast as little more than a rhetorical flourish on Vastey’s part, a rote invocation of insurrectionary language that might have given his mixed audience at the Café des étrangers a jolt but that could not have been seriously meant at a time—over thirteen years removed from the declaration of national independence—when a future for Christophe’s Haiti and the cause of antislavery so evidently appeared to depend upon gaining international recognition of its independence, with the help of the regime’s abolitionist friends and a more concerted media campaign on its behalf, of which the translations of Vastey would form no small part.18 And no doubt there would be some truth to this reading. But if we look not forward to the final years of the regime—when, in the words of another Christophean scribe, hopes for ‘the complete liberation of our country and the definitive enfranchisement of this Kingdom’ seemed to rest with philanthropists abroad (Chanlatte, 1819, 15–16)—but double back to the summer and autumn of 1814, just two short years before Vastey gave that toast, then the lived intensity of his post/revolutionary appeal to revolutionary violence becomes rather more appreciable, for it was during this time that l’an IIème of independence seemed as if it might realistically be on the point of reverting to Year Zero, with the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy and the threat of a new invasion of the former Saint-Domingue by its ex-colonial masters. It is this moment of absolute urgency to which Vastey is responding with Le système colonial dévoilé, the one major text of his that would not be translated into English.19 While the lack of this translation can doubtless be attributed to the fact that the book’s publication preceded by several years the mounting of the aforementioned media campaign in English, one might also venture that there is something dangerously ‘intemperate’ about this particular work, which can be accounted for by the situation of urgency in which it was produced, and which distinguishes it from the three later works of his that were translated into English. In order to prepare the ground for reading what is arguably Vastey’s most powerfully rendered denunciation of slavery and the colonial system, it will thus be necessary to supply a contextualizing account of the months leading up to the publication of Colonial System in October 1814.

At an earlier juncture in his lengthy letter of 10 July 1820, Clarkson had occasion to remind Christophe that in 1814, ‘soon after the restoration of the Bourbons, and when Monsieur Malouet was the Minister of the Marine and Colonies, it was determined to reduce Hayti to a slave colony by force of arms, but the Treaty of Vienna, and other circumstances put a stop to these proceedings’ (168v). This one sentence of Clarkson’s about France’s, and specifically Malouet’s, efforts after the fall of Napoleon to destroy the independent nation of ‘Hayti’ and restore the slave colony of ‘Saint-Domingue’ contains, in nuce, the sordidly predictable story of colonial (re)conquest that I will be expanding upon in this second section of the Introduction in order to set the scene for Vastey’s emergence into print in October of that momentous year.

Between 1804 and 1814, following upon the final defeat in November 1803 of Napoleon’s forces in French Saint-Domingue,20 ‘relations between Haiti and France were almost totally broken off’ (Brière, 52). Toward the end of that period, however, with Napoleon’s fortunes flagging in Europe after the Russian campaign of 1812 and recent defeats in Germany (October 1813), and with the signing of a European peace treaty and perhaps even the collapse of the Napoleonic regime apparently in the offing, both Christophe and Pétion sensed that this relatively quiescent state of affairs was not likely to last much longer, and that it might be time to take the initiative in securing the future of Haiti (or, more exactly, the two Haitis). In his polemical writings of 1815 directed against the southern republic, Vastey repeatedly accused Pétion of sending secret agents to France in the final months of 1813 and negotiating a treaty with Napoleon that would have resulted in a restoration of French rule (see, e.g., 1815b, 72; 1815c, 14). Notwithstanding Vastey’s sarcastic invectives at the expense of those ‘amphibian-like’ agents of Pétion’s and their ‘perfidious’ mission across the seas (1815b, 74), Napoleon’s changing fortunes also induced Christophe to send his own secret agents to France in March 1814, not, certainly, to negotiate a return to French rule but to sound out the conditions for French recognition of Haiti’s independence. These two agents were none other than Vastey and his fellow scribe, Prézeau. The two men would get as far as London, by which time (early April) the French Emperor had abdicated, and the Bourbon monarchy had been restored to the throne in the person of Louis XVIII.21

The Kings of France and Haiti had a common enemy in Napoleon, so the Christophean regime had at least some hope, in the spring and summer of 1814, that the defeat of the man who in 1802 had attempted to reimpose slavery in Saint-Domingue might open the door to official recognition of Haitian independence. As Vastey recalled in a pamphlet entitled À mes concitoyens, published in January 1815: ‘We saw with satisfaction the fall of this oppressor of the world, and the reestablishment of the House of Bourbon on the throne of its ancestors; we had reason to hope that his Majesty Louis XVIII—schooled in misfortune and adversity, and having long resided in England, in the midst of such an enlightened people—would have adopted their philanthropic principles!’ (1815a, 3) In a Proclamation of 15 August, and then again in his important Manifesto of 18 September, Henry Christophe gave voice to this hopeful expectation: ‘We hope that [Napoleon’s] fall will give peace and repose to the world; we hope that the return of those liberal and restorative principles guiding the European powers will lead them to recognize the independence of a people whose only wish is the enjoyment of peace and commerce, the goal of all civilized nations’ (1814, 14), going on to add that it was ‘not presumptuous’ to suppose that Louis, ‘following the impulse of the philanthropic spirit that his family had previously exhibited’, would ‘recognize the independence of Hayti’ and thereby effect ‘not only an act of justice, but a reparation of the evils we have suffered under the French government’ (16). Already, though, Christophe was sounding a note of worry that the ‘caste’ of ex-colonists, the ‘enemies of humankind’, would once again, as they had with Napoleon in 1802, ‘employ all their usual methods to drag the French cabinet into a new enterprise against us’ (9). In language that ‘harkens back to the style of the French Revolution, Year Two [the Jacobin era]’ (Benot, 1992, 175), Christophe’s Manifesto concludes with a powerful affirmation of his refusal ever to capitulate to the French, and a promise that ‘we will bury ourselves under the ruins of our country rather than suffer an attack on our political rights’ (18).

Christophe’s fears regarding the influence of the ex-colonists would prove well founded. In À mes concitoyens, after describing the hopes generated by the fall of Napoleon, Vastey immediately went on to lament: ‘Vain hope! No sooner had this monarch mounted the throne of his forefathers than the ex-colonists of Saint-Domingue surrounded him, plaguing him with their clamorous demands’ (3). Letters, reports, and projects concerning the conquest and reestablishment of Saint-Domingue would flood the offices of the Ministry of the Marine and Colonies in the months following upon the allied occupation of Paris at the end of March. In the earliest such letter to be found in the Ministry’s files, written on 6 April (the very day that Napoleon abdicated and the French Senate voted to recognize Louis XVIII as King of France), we find a former secretary of Toussaint Louverture’s, René Guybre, congratulating the King’s nephew, the Duc d’Angoulême, on the defeat of the ‘usurper’ and on ‘the happy return to France of the Empire of the Lily and of its legitimate prince’. Guybre sees the return of the Bourbons as clearing the way for a quick restoration of French rule in Saint-Domingue, especially if negotiators were to focus their efforts on Pétion, ‘more capable [than Christophe] of feeling how essential it is for him, as for his class, to gain the safety that his legitimate prince offers’.22 For the clamouring mass of ex-colonists who believed that peace in Europe had ‘reopened the route to Saint-Domingue’,23 this distinction between a pliable Pétion and an inflexible Christophe would prove a constant theme of both their private communications with the Ministry and their published works—a fact that the Christophean regime was quick to pick up on and use to good effect in the so-called guerre des plumes that erupted between the two Haitis the next year, a media war that would, to anticipate matters, occupy much of Vastey’s time: ‘Read all the foreign gazettes’, he urged his public in the Spring of 1815, ‘read the reports of the Charaults and the Berquins—all the writings of the French ex-colonists affirm that Pétion is devoted to France’ (1815c, 13).

Vastey concludes his lament in À mes concitoyens by noting that hope of a positive resolution to the problem of Haitian independence had been rendered all the vainer by the fact that Louis XVIII immediately placed an ex-colonist in charge of the Ministry: the ‘shameless’ septuagenarian Pierre Victor Malouet (3), who on 13 May was officially introduced as the King’s Minister of the Marine. In the words of another Christophean scribe, the choice of ‘such a monster’ could ‘only excite our indignation’, given his longstanding commitment to ‘slavery and the destruction of our kind’ (Prézeau, 26–27); it sent a clear signal to the ex-colonists, and to the ex-colonized, that recovering Saint-Domingue was near the very top of the new government’s political agenda. As one former colonist wrote to him from Bordeaux shortly after his appointment, Malouet was the perfect man for the job: ‘You’re a landowner in Saint-Domingue, you’ve resided there, you’ve served in varying capacities as an administrator in the colonies, who can know them better than you?’24 Malouet did indeed ‘know’ the colonies very well: in 1767, in his late twenties, he had come to Saint-Domingue as a colonial administrator, spending seven years there while marrying into a Creole family and becoming the owner of several flourishing plantations in the north; he also served in French Guiana, and in 1788, after a long stint working for the Ministry of the Marine in Toulon, he left for Paris, devoting himself over the next several years to the double task of preserving the monarchy and combating abolitionism (albeit, as we will see, in the name of an ostensibly ‘reformist’, juste milieu politics that, while insisting upon slavery as the fundamental base of colonial society, nonetheless acknowledged the need for ‘ameliorations’ in master–slave relations). As an exile in London, he served during Britain’s partial occupation of Saint-Domingue from 1793 to 1798 as official representative of the colony’s anti-republican planters, who had thrown their lot in with the British; and when the British left Saint-Domingue, he then turned to Napoleon as the next best hope for putting an end to the ‘democratic delirium’ that had resulted in a lowly black man like Toussaint Louverture rising to a position of supreme power in the colony (1802, 4.12). By 1814, in his seventies, Malouet had become his own best hope for restoring and ‘reforming’ the old colonial order.25 In a letter of 12 July he described himself as ‘entirely occupied at the moment in getting this important colony to submit to His Majesty and assuring France of the immense advantages that come with its possession, but without’, he added, ‘having to resort to the use of force in order to attain this goal’, since His Majesty’s intention was to take such drastic measures ‘against St. Domingue only if it were to prove indispensable in getting the colony to submit’.26 By gentle persuasion or military might, in the summer of 1814 Malouet was committed to plotting an end to Haitian independence and instituting a new and ‘improved’ version of what he himself had long ago dubbed ‘the colonial system’.

Opening out, as it does, onto a globally resonant vision of what Sartre, in his 1956 essay ‘Colonialism is a System’, would term ‘the infernal cycle of colonialism’ (2006, 51), Vastey’s unveiling of ‘the colonial system’ in his 1814 book extends well beyond a critical encounter with Malouet, his ideas, and his language. However, given that Malouet’s particular usage of the phrase is what generated the emergence of Vastey’s broader critique of colonialism, a brief review of the ex-colonist’s deployment of it is in order here. Malouet laid claim to the phrase in his 1802 preface to a hitherto unpublished work of his from 1775 on Saint-Domingue.27 In this preface, he insisted that his ideas from the 1770s for reforming the colonial administration were still of great value in 1802; they continued to offer a viable blueprint for the ‘new era that is beginning’, inaugurated by Napoleon’s decision to wrest control of Saint-Domingue from Toussaint (4.76). Looking forward to ‘the restoration’ that would come after the conquest (4.47), and relieved at the thought that ‘colonists of our blood’ would no longer run the risk of having their throats slit or of being subjugated by the blacks—for ‘that is the plan of the leaders of the African caste, the horrible but necessary result of the equality of rights’ (4.32–33)—Malouet traced the recent troubles of Saint-Domingue to the ‘absurd’ revolutionary idea that metropolitan centre and colonial periphery could be governed according to the same legislation:

Experience teaches us that the doctrine and principle of liberty and equality, transplanted to the Antilles, can produce nothing there except devastation, massacres, and conflagrations. What the founders of a society composed of masters and slaves thus needed to do was protect it from any political influences capable of inducing the slaves to slit the throats of their masters; and that is precisely why this society should not have been subject to [devoit être affranchie de] any legislation in the founding people’s own land that proscribes slavery.

That principle being the fundamental base of what I call the colonial system, I insist on it, as an obvious fact, and I parry in advance any and all reasoning and arguments that one might wish to marshal in order to evade it. (4.14)

Colonial society in the Antilles depends for its very existence upon ‘its base, which is slavery’ (4.15). This, for Malouet, is the practical state of affairs that needs to be taken into account by even the most enlightened administrator, and that is rendered all the more practicable by the ‘natural’ docility of the enslaved: ‘One must not’, Malouet noted, ‘consider negroes as a people aspiring to independence and collectively engaged in finding the means to secure it. This species of men is, on the contrary, naturally disposed to obedience’ (4.56). But, he cautioned, the colonial system, in order to be a system and not merely an instantiation of what he elsewhere calls ‘colonial despotism’ (5.19), nonetheless has to be carefully regulated, which requires finding a juste milieu between ‘unlimited slavery’ and ‘proclaimed freedom’ that colonial administrators in the past had often proved unable or unwilling to enforce (4.21). Master–slave relations are the ‘fundamental combination’ upon which colonial society depends, and hence should not be meddled with, but that does not mean they cannot be rectified (4.19): ‘the authority of the master must be respected’, for instance, ‘but his fantasies, his anger, must be curbed’ (4.23). The colonial system must be restored and reformed, resulting in ‘a servitude better ordered than the old version’ (4.83–84); even certain shifts in terminology might facilitate this happy result, such as substituting the term non libre for the word esclave (4.23; ‘Since the word slave represents to us a man enchained, let the label of not free be substituted for it’).28

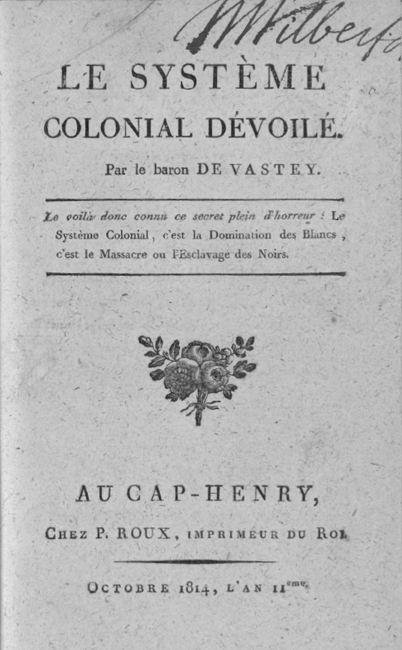

In a direct commentary on this fine distinction of Malouet’s, Vastey sensibly responded: ‘What does the name matter, if the fact exists?’ (1814b, 7) Vastey would joust with Malouet for the entirety of his career as a Christophean scribe, beginning in October 1814—in the twenty-four-page companion piece to Colonial System, the Notes à M. le Baron de V. P. Malouet, where he offered a close reading of some of the most objectionable assertions in Malouet’s 1802 Introduction—and ending with his last book, where he reminded readers that ‘the foundations of the colonial system rest on slavery and colour prejudices with a view to preserving the supremacy of whiteness, which the ex-colonists guard so jealously’ (1819, 4). What differentiates Colonial System from Vastey’s other works in this regard is that the explicit critique of Malouet is supplemented by a parodic appropriation of his language, a strategy that is most evident in the book’s paratexts: its title, obviously, but also, and especially, its unattributed epigraph, ‘Here it is, revealed, this secret full of horror. The Colonial System: White Domination, Blacks Massacred or Enslaved’ (‘Le voilà donc connu ce secret plein d’horreur: Le Système Colonial, c’est la Domination des Blancs, c’est le Massacre ou l’Esclavage des Noirs’; see Figure 2). As an initial point of entry for Colonial System, this epigraph can be read on its own terms, as a simple if provocative summary of the book’s contents, rendered all the more emphatic by the typographical doubling of italic and roman script and the reliance on a Gothic vocabulary of secrecy and horror, of the sort that had become such a staple of both proand antislavery representations of the Haitian Revolution.

The epigraph becomes immeasurably more interesting, however, once we realize that it is an allusion to and distortion of one of the more lurid moments in Malouet’s 1802 Introduction. Midway through the Introduction, interrupting an extremely dry account of the need for fiscal reform in the colony, Malouet’s language becomes suddenly energized as his thoughts turn to the recent cessation of hostilities between France and Britain, and the ongoing resistance of Toussaint Louverture to General Leclerc’s forces, which had arrived in the colony in early February of that year with the intent of ‘demolishing Louverture’s power and severely restricting the access of the former slaves to political power’ (Dubois, 2004, 259). ‘As I write, peace is proclaimed, and yet’, Malouet fumed, ‘in the torrid zone French blood is still flowing. A black man, a mule driver grown old in slavery, disputes the sovereignty of Saint-Domingue with the peace-making hero of Europe’ (4.46). This muletier (Malouet does not deign to refer to Toussaint by name) ‘permitted whites to live in a state of degradation while they were under his orders, but he slits their throats as soon as the French Government tries to reassume its place in the colony’. Malouet then continues: ‘Here it is, revealed, this secret full of horror. Liberty for the blacks: Domination for them! Whites massacred or enslaved. Fields and cities burned to the ground’ (4.46; ‘Le voilà donc connu ce secret plein d’horreur: la liberté des noirs, c’est leur domination! c’est le massacre ou l’esclavage des blancs, c’est l’incendie de nos champs, de nos cités’). This passage, which concludes with Malouet affirming that ‘these blacks have evidently forfeited their liberty: let them return to the yoke!’ (4.47), is straightforwardly refuted by Vastey in his Notes (1814a, 13–15), but the refutation of Malouet in the epigraph to Colonial System is of another, more literary order. As an example of ‘parodic (re)citation’ (Bongie, 1998, 290), it both reverses and reiterates colonial discourse in a manner that clearly anticipates the sort of counter-discursive work performed by later postcolonial writing. Simple reversals of black and white—of the sort associated, say, with the poetics of Negritude—are foregrounded in the epigraph, but are clearly not the whole story. For instance, the fact that the epigraph offers not a spontaneous deployment of Gothic language but a self-conscious reiteration of Malouet’s eager recourse to it opens a space for critical reflection on the process of ‘making history Gothic’ that was so typical of proslavery accounts of the ‘horrors of Saint-Domingue’, and on how that process served the reactionary purpose of ‘reinforc[ing] the construction of the revolution as unthinkable’ (Clavin, 2007, 29); it also creates a space for confronting the question—a pressing one, given Vastey’s own evident commitment to unveiling secrets full of horror—of whether ‘a Gothic language of antislavery’ truly challenges, or subtly reinforces, that purpose (Cleves, 143). Throughout Colonial System, Vastey’s parodic relation to Malouet incites these sort of difficult, if productive, reflections—as when in his opening address to the King, to cite one last paratextual example, he identifies Christophe as the Haitian leader who finally uprooted ‘the ancient tree of slavery and colonial despotism’, thus perversely merging the revolutionary language of Dessalines (‘ancient tree of slavery’) and the ‘reformist’ language of Malouet (‘colonial despotism’).29 What are we to make of this monstrous hybrid, and the textual practice that can yoke together two such very opposed voices?

In my essay contribution to this volume (Chapter 3, below), I address some of the interpretive challenges posed by the textual hybridity of Colonial System, focusing in particular on forms of intertextual appropriation made possible by acts of reading (and listening). At this point, however, we need to return to the summer of 1814 and resume our chronological narrative about Restorationist plans for reopening the ‘route to Saint-Domingue’. While virtually every ex-colonist who wrote to the Ministry of the Marine concerning Saint-Domingue during that time (and/or flooded the book market with plans and reports on the subject) was agreed on the desirability of this restoration, they differed as to the ease or difficulty of achieving it. For some, such as the Creole Jean-Jacques de la Martellière, ‘the means of restoring the colony of Saint-Domingue and the Colonial system’ (to cite the title of the thirty-six-page report he submitted to Malouet on 8 June) were well within France’s reach. If France were not in a position to subdue Saint-Domingue on its own, then ‘all the other colonial powers ought to join forces with France to launch a crusade against an anti-colonial society [former une croisade contre une société anti-colonial] whose very existence, let us be frank, is a disgrace to all colonial governments’. However, he continues, this is happily not the case, because ‘France will need to use only a small part of its forces to reestablish its authority and the empire of its laws over the colony; she merely has to want to do so. One should not exaggerate the difficulties involved in subduing the insurgents and restoring the plantations of St. Domingue’.30 Others, by contrast, stressed ‘the great difficulties that will have to be overcome if we are to retake it’.31 As one fourteen-year resident of the colony, a certain Morin, put it: ‘The attempt made after the peace of Amiens [in 1802] to secure its conquest will no doubt be a lesson to the current Government, which must not blind itself to the fact that the unfavourable result of that campaign has added to the difficulties of any new one that would reunite France with the finest of its colonies’.32 Adding to these difficulties, Morin subsequently noted, was the absolute intransigence of Christophe, ‘whom it is impossible to win over’ (5), ‘the negro in command of the Province of the North, and the negroes commanding under him, having no interest in the establishment of a colonial system that would take away their authority’ (9). Thus, he concluded, ‘there is only one means to regain the colony without destroying it, and that is to treat with Pétion’ (8), which will be possible only if the condition of the hommes de couleur is ‘ameliorated’ and ‘concessions are made that will attach them to the colonial system’ (8).

Malouet himself advised Louis XVIII that regaining Saint-Domingue would be neither as easy nor as difficult as people were making it out to be. ‘The restoration of St. Domingue, considered by some to be impossible and by others as a very simple matter, is neither the one nor the other, it seems to me’, he wrote in June.33 He expressed optimism that ‘it would be possible to keep the class of cultivators in a state of slavery (under a gentle regimen)’, but cautioned—with his usual sensitivity to terminological niceties—that ‘the word itself must be suppressed at all costs: this class must be attached to the glebe [like serfs], and produce the same results only in a different guise’. In order to ascertain whether the use of force would be required to bring about this restoration of French rule, the first step was ‘to send secret agents out to St. Domingue to assess the current state of that colony’, Malouet argued in a letter of 24 June to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, whose help he sought in facilitating such a mission (which already had royal approval).34 The three men selected for the mission (Dauxion Lavaysse, Franco de Medina, Draverman) were given secret instructions by Malouet on how to conduct themselves,35 which contained, among other things, repeated assertions regarding the necessity of reimposing slavery in ‘the colony of Saint Domingue’,36 and of creating a new five-caste racial hierarchy there,37 as well as assurances that the King had already given the order to prepare an armed expedition should the present negotiations not bear fruit, and that no one should doubt that ‘if the King of France wanted to bring all his forces to bear on a handful of his rebel subjects who make up scarcely one one-hundredth of the population of his dominions… he would break them, even if it meant having to exterminate them’ (qtd. Vastey, 1819, suppl. 53).

Malouet’s secret agents left Paris on 30 June, travelling first to England, and arriving in Jamaica almost two months later, on 26 August. From there, Lavaysse, in his capacity as ‘Principal agent of His Excellence the Minister of the Marine and Colonies’, sent a letter of introduction to Pétion on 6 September, and to Christophe on 1 October. The letter to Christophe, ‘a strange mixture of stupid flattery, and still more stupid intimidation’, as one British commentator put it a few years later (Barskett, 366),38 predictably generated ‘a feeling of the greatest indignation’ when it was read out to Christophe and his privy council and it became clear that France was offering not independence and a reparation of injustices but ‘a tissue of insults, fanfaronades, and lies’ (Vastey, 1819, 208). Christophe convoked a General Council of the Nation on 21 October, and had Lavaysse’s letter read out to them. In his 1819 Essai, Vastey provides a powerful account of what it was like to be in that room and watch the electrifying effect the letter’s contents had on its listeners:

Among the members [of the council] there were some who had worn the chains of the French, who had been branded by them, whose mutilated limbs still bore the mark of them, attesting to their long and cruel sufferings, and to the barbarism of our tyrants. Others remembered having watched fathers, mothers, brothers, sisters, relatives or friends being hanged, burned, drowned, or eaten by dogs. And it was to these old warriors, their bodies covered in noble scars, who had watched the sanguinary hordes of the Leclercs and the Rochambeaus flee before them, that this proposal was being made: that they once again submit to the yoke of those odious tyrants, that they choose between slavery and death! On the instant, all the hatred and the desire for vengeance that had been lulled by the passage of time reawakened with an incredible strength and vigour. (1819, 212–13)

I have quoted at some length Vastey’s account of this scene from October 1814 because it exemplifies the dynamics of collective memory that are at the heart of Colonial System (as Marlene Daut shows in her contribution to this volume). The visceral memories on display here are what produced this book, published that same month of October 1814, and they are what the book is itself intent on producing: awakened memories that cannot be simply cordoned off from the present but that make themselves felt on the body, avec une force et une énergie incroyables. This representing of the colonial past and its horrors draws fully-fledged citizens exercising their civic duty as membres of a national council (back) into a disturbing identification with their membres mutilés, the parts of their enslaved bodies that were tortured by the French; but it also has the energizing effect of reproducing a vision of these same masterful colonists in retreat, fleeing those whom they once fed to the dogs. Notwithstanding, or precisely because of, the traumatic memories of subjection it provokes, the reading of Lavaysse’s letter to the representatives of the national body reawakens the active vision of a revolutionary future: ‘The members of the council rose spontaneously, and swore on the point of their swords, in the name of the Haytian people, that they would rather be exterminated down to the last than renounce their liberty and independence by submitting to France!’ (213)

Oblivious to the hostile reception of his letter in Christophe’s kingdom, Lavaysse left Kingston for the southern republic on 17 October, at the invitation of Pétion, and arrived in Port-au-Prince on the 24th, where he was again overcome with fever, delaying the start of negotiations with Pétion and his chief aides Inginac and Boyer until 8 November. By all accounts, their discussions in the ensuing two weeks were cordial, but the mood changed dramatically on the 20th when envoys from Christophe arrived in Port-au-Prince with freshly printed copies of the General Council of the Nation’s resolution to live free or die, as well as, and much more importantly, copies of Malouet’s secret instructions to his agents, in which were plainly stated France’s intention of regaining sovereignty over ‘Saint-Domingue’ and of restoring some form of slavery in the colony. How had Christophe gained hold of those instructions? Shortly after the meeting of the Council, another of Malouet’s agents, Franco de Medina, had been arrested on 11 November while reconnoitring Christophe’s territory; the secret instructions had been found on his person and, upon subsequent interrogation (17 November), he had expanded on France’s ongoing plans to retake the colony with Pétion’s help. As per the King’s policy that ‘all documents received from abroad by His Majesty’s cabinet having to do with the French government be made public by means of the printing press’ (Vastey, 1816a, 1), the instructions were immediately published and rushed to Port-au-Prince.

We will never know Pétion’s true motives for ‘temporizing with Lavaysse’ (Griggs, 59), and leaving the Frenchman with the impression when he first met with the President and his top aides that ‘they seemed disposed to recognize the sovereignty of France, on condition that she not send any garrisons’,39 but it is certain that the ‘making public’ of these secret instructions forced Pétion’s hand, leading him to suspend negotiations and reassure his fellow citizens of his unwavering commitment to Haitian independence (first in an assembly of generals and magistrates on 27 November and then in a public Proclamation on 3 December). At the same time, it also led him to confirm, for the first time publicly, a central component of those abruptly terminated negotiations, namely, his willingness to pay an indemnity to France for its lost property, ‘to submit to pecuniary sacrifices’ as a sign of the republic’s favourable disposition with regard to its former colonial master (a point to which I will return at the end of this section). Pétion and Lavaysse parted on good terms in early December. Even in February 1815, writing from London, the latter was sanguine about the future state of negotiations with the southern republic, especially if the ‘absurd’ idea of restoring slavery in the colony were to be abandoned, but warned that nothing could be expected from Christophe: ‘Permit me to say it, Your Excellency, even had a Grégoire or a Wilberforce been sent to speak to Christophe in France’s interest, their efforts would have had no effect on that madman’.40

As it happens, Vastey played a central role in the Medina affair. Whether it is true or not—as a former British consul to Haiti, Charles Mackenzie, claimed in 1830—that ‘by the intrigues and treachery of Vastey, it was discovered that he [Medina] was possessed of documents calculated to promote dissension’ (2.84; see also Madiou, 5.259), Vastey certainly made his presence felt at the Te Deum ceremony organized by Christophe on 17 November in Cap-Henry to celebrate the French spy’s capture. In a packed church, with Medina himself in attendance standing on a stool for all to see, thanks were given and the secret instructions were then read out to the crowd, along with the minutes of the meeting of the General Council of the Nation. After Chevalier Prézeau’s reading of the minutes, it was Vastey’s turn to speak. First he read from his colleague Prézeau’s just-published Réfutation de la lettre du général français Dauxion-Lavaysse, and then from his own Notes à M. le Baron de V. P. Malouet. As the more incendiary comments of Lavaysse and Malouet were read, and refuted, the crowd became increasingly agitated, and officers were seen reaching for the hilt of their swords at each offensive passage. As reported in the Gazette royale of 20 November, Medina’s legs began to shake, he started gasping for air, and eventually fell to his knees. But,

when he heard the thundering words of Monsieur the Baron de Vastey— ‘Friends! let nothing stop the anger you feel upon hearing those words “Slave” and “Master”; the tocsin of liberty has sounded! […] Hasten to arms, let your torches be lit, let the carnage begin, and vengeance be taken!’—Franco, believing that he saw thousands of bayonets pointed toward his chest, and seized with fright, took a decided turn for the worse. Vinegar and a cordial were required to restore him from his useful terror. What a pity that his two colleagues, Dauxion Lavaysse and Draverman, could not be by his side; what a lovely trio they would have made! And you, you debilitated wretch [et vous vieux cacochyme], who allowed your retainers to play the dangerous role of spy, o Malouet! what a delightful figure you would have made in the company of these ambassadors of yours. (2–3)

One can scarcely imagine a more dramatic counterpoint to Clarkson’s Vastey, modestly working behind the scenes to produce a few observations for the edification of a foreign audience.41 Here, in an equally but differently scribal performance, orality supplements writing, and the ‘powers of oratory’, flowery or otherwise, produce an immediate effect on Vastey’s friends (and the one enemy among them), a vernacular audience moved by his written words despite the fact that the community to which it belongs ‘remained overwhelmingly illiterate and indebted to oral forms of communication’.42

It is altogether possible that the journal article in the Gazette was written by Vastey himself. Regardless of its provenance, what the author of this blistering apostrophe to the vieux cacochyme did not know, but would soon find out, is that he had been addressing not the absent but the dead. Malouet had in fact died over two months before, on 7 September, but news of his death would only reach Cap-Henry a week or two after the Te Deum ceremony. One of Vastey’s fellow scribes, Baron de Dupuy, began a work of his published in December by noting that he had just learned of Malouet’s death: ‘It is, in truth, a very great loss for the ex-colonists, especially as he was perhaps the person in France most attached to the colonial system and the most zealous champion of the slave trade. His death’, Dupuy added,

must have thrown the partisans of slavery, the votaries of the slave trade into horrible convulsions; how they must have plotted, what strings they must have pulled, to replace that Minister with another ex-colonist of the same religion, the same tenacity, and whose despicable prejudices might ensure that this same system, with its plan for ending the independence of Hayti, will be followed to the letter. (1814a, 1–2)43

In another book that rolled off the printing press of Pierre Roux in December,44 the King’s Foreign Minister, Julien Prévost (the Comte, and later Duc, de Limonade), likewise noted, in its concluding paragraphs, that news of Malouet’s death had only just reached him, and went on to remark that it was a pity ‘this fiercest and most formidable of adversaries did not have the opportunity to learn about the sterile outcome of the mission of his three spies; but his spirit lives on in the soul of the ex-colonists’ (1814, 36). Malouet’s spirit did indeed outlive him, for, despite an official disavowal of the secret instructions and the bungling manner in which the mission had been conducted, plans for a military expedition were being actively pursued at the time Lavaysse finally returned to Paris at the end of February.

The unsuccessful nature of the secret mission to Haiti ‘would have made the projected military enterprise, decided upon in February 1815, an inevitability, had the return of Napoleon not upset all those plans’ (Benot, 1992, 175). Napoleon’s return from Elba in March ‘put an end to [French] plans for the conquest of Haiti’ (Griggs, 59), and during his Hundred Days of power the restored Emperor further complicated the situation by abolishing the slave trade in France, effectively forcing the Bourbon monarchy’s hand in this matter when it was restored for a second time, in June 1815. In the two Haitis, meanwhile, the stark differences between Pétion’s friendly temporizing with Lavaysse and Christophe’s intransigent treatment of Medina provided the grounds for polemical exchanges between the rival regimes that year: the so-called guerre des plumes that generated Vastey’s next five publications (1815a, 1815b, 1815c, 1816a, 1816b) after the two inaugural texts from October 1814. Notwithstanding these bitter exchanges, the dramatic events of November prompted a growing commitment on the part of both governments to overlook internal differences in the case of an actual attack on their territories. The French government, to be sure, ‘persisted in its efforts to persuade and cajole its former subjects into submission’ (Nicholls, 1979, 48), but as the head of a second, rather more diplomatic, mission to Haiti that was sent out in 1816 reported to Louis XVIII upon his return to France, ever since the revelation of Malouet’s secret instructions ‘the leaders can think of nothing but separating from France, they have redoubled their efforts at filling everybody’s head with the idea of independence, and in Christophe’s territory as in Pétion’s they are all fanaticized by that word’.45 It was becoming clear to an ever-growing number of government officials, and even to some of the less obtuse ex-colonists, that the dream of restoring French sovereignty over the former colony would have to be nuanced. Over the next several years, arguments in favour of direct military action became less and less frequent: even a diehard like General Étienne Desfourneaux, a veteran of the Leclerc expedition, when arguing in 1817 for ‘the restoration of a vast and flourishing colony’ and laying out the ‘general principles for a new colonial system’,46 felt compelled to spend much of his time refuting ‘the partisans of a calamitous emancipation’ (5), who were willing to renounce French sovereignty in return for the payment of indemnities. ‘The idea of emancipating Saint-Domingue’, Desfourneaux fulminated, ‘and of being paid indemnities in return, as the reward for this huge concession, is an exorbitant idea [une conception extravagante] of the false friends of the Blacks’, which would have the deleterious effect of ‘legitimizing revolt, ceding the property of French subjects to savage hordes’, and allowing ‘insurgent Negroes to take their place among the American powers’ while according the French government ‘no other compensation than that of an illusory and humiliating promise’ (28).

As Desfourneaux’s livid reaction to this conception extravagante makes clear, Pétion’s idea of indemnities (which, in a typical erasure of Haitian agency, Desfourneaux attributes to French philanthropists) was gaining in momentum as the tumultuous decade drew to a close. By 1820, Clarkson could respond in the negative, and with the greatest of certainty, to Christophe’s question, ‘Will France ever fit out an expedition expressly for the purpose of conquering Hayti?’ ‘The universal answer to this in France’, Clarkson wrote in his 10 July letter to the King, ‘is—No—any French Ministers collecting an armament solely French, and solely for such a purpose, would be considered to be mad, or like persons who should attempt to jump from the Earth to the Moon’ (164v). Rather than shooting for the moon, in its search for colonies France would henceforth begin looking elsewhere and, in the case of Algeria, much closer to home: as one historian has recently argued, ‘the conquest of Algeria, in its initial stage’, from the late 1820s to the seizure of Algiers on 5 July 1830 and the subsequent appointment of Bertrand Clauzel (who served under Leclerc and Rochambeau in the Saint-Domingue expedition of 1802–03) as first governor of French North Africa, may ‘be construed as an attempt to provide France with a substitute for the riches of Saint-Domingue rather than a new colonial departure’ (Todd, 169–70). When Frantz Fanon arrived in Algeria in 1953, he would encounter there a flourishing avatar of the same old colonial system that had been developed across the Atlantic in Saint-Domingue: in this regard, there can be nothing surprising about the many powerful affinities between Vastey’s and Fanon’s systemic critiques of colonial governance.