1

How the Wise Men Got to Gotham

The Fools of Chelm Take Manhattan

“A man journeyed to Chelm,” Woody Allen says in the opening words of his “Hassidic Tales, with a Guide to Their Interpretation by the Noted Scholar,” published in the New Yorker in June 1970, “in order to seek the advice of Rabbi Ben Kaddish, the holiest of all ninth-century rabbis and perhaps the greatest noodge of the medieval era.”1 How much Jewish cultural literacy does the author of this sentence implicitly expect of the New Yorker’s readership? Clearly, readers should be acquainted with a large enough set of American English Yiddishisms to know that the Slavic-derived word noodge means “a bore.”2 But, equally clearly, it is presumed that such a reader, circa 1970, could be expected to understand that a journey to Chelm would result in an encounter with folly.

Sure enough, craziness ensues. The traveler’s purpose is to ask the rabbi of Chelm where he can find peace. In response, the rabbi asks the man to turn around and proceeds to “smash him in the back of the head with a candlestick,” then chuckles while “adjusting his yarmulke.”3 Then comes the “interpretation of the noted scholar,” which explains nothing at all. It only baffles the reader further by explaining that the rabbi was preoccupied with, among other things, a paternity case. In any event, according to the commentator, the man’s question is “meaningless,” and “so is the man who journeys to Chelm to ask it. Not that he was so far away from Chelm to begin with, but why shouldn’t he stay where he is?”4

Allen’s premise is that his audience will grasp that to be “not far from Chelm” is to be mentally not far removed from the fictitious wise men of the imaginary place in which all (Jewish) fools live. In this piece, written in part as a parody of Martin Buber’s Tales of the Hasidim, Allen uses the fictitious foolish town of Chelm to set the frame for his tales illustrating the silliness of the mystical mind-set.5

A generation later, Chelm was invoked again in Nathan Englander’s story “The Tumblers” (1999). Attributes of literary Chelm are also silently transferred to Trachimbrod (Ukrainian: Trokhymbrid, about one hundred miles east of Chelm), another real place made, Chelm-like, to double as an imaginary one in Jonathan Safran Foer’s Everything Is Illuminated (2002). Numerous other American Jewish writers of recent decades have produced imaginative work wholly or partly inspired by the Chelm theme, but these have often been aimed at more limited audiences.6 Notable among these works are Jenny Tango’s 1991 feminist graphic novel Women of Chelm; Judith Katz’s lesbian novel Running Fiercely toward a High Thin Sound (1992), set in New Chelm; and Keynemsdorf (2010), a literary novel in Yiddish by the Russian American Boris Sandler.7

Sandler’s novel returns us to the linguistic medium in which Chelm became big in America and in which New York became the source of most new Chelm literature. As early as the 1920s, while Chelm was still a favorite topic for Yiddish authors in Europe, a parallel body of work from writers newly arrived from Russian Poland and Galicia started to form a corpus that expanded greatly after the Holocaust, while at the same time European production came to a halt.

Among the major contributors to Chelm literature in America were three writers who were close friends: Aaron Zeitlin (Arn Tseytlin, 1898–1973), Yekhiel Yeshaye Trunk (1887–1961), and Isaac Bashevis Singer (Yitskhok Bashevis, 1902–1991).8 The three met in the famous Fareyn fun yidishe literatn un zhurnalistn in Varshe (Association of Jewish Writers and Journalists in Warsaw) at 13 Tłomackie Street, during the period when Menakhem Kipnis (1878–1942) was “the person in charge” of the club, as Trunk remarked in his condescending description of him.9

It was Kipnis, more than anyone else, who had popularized Chelm tales, publishing a long series of them in the Warsaw Yiddish newspaper Haynt in 1922 and 1923. Zeitlin and Singer published in Haynt as well; Trunk’s books were reviewed there; and the three of them must have come across many Chelm stories in written and oral form while in Warsaw during the very years these tales were at the height of their fame.10 All three writers came to New York in the late 1930s or early 1940s, but each contributed to the body of Chelm literature with a different agenda, at a different time, and in a different genre.

Zeitlin’s play Khelemer khakhomim (The wise men of Chelm) was performed in 1933, six years before he arrived in the city. Trunk wrote his novel of Chelm, published in 1951, while the impact of the Holocaust was still sinking in. And Singer’s first Chelm story, printed in Forverts in 1965, at the height of the Cold War, led to a series of political satires in Yiddish that he published in that newspaper, pieces that later, depoliticized, served as the basis for his children’s literature.

These three writers exemplify the ways in which Chelm has been treated in an American climate: as a device enabling writers to explore religious questions, examine Jewish history, and discuss American and world politics. This continuing Chelm tradition also illustrates how multilingualism helped shape American culture over an extended period of time.

Teacher on the Roof: Chelm on the Stage

When Maurice Schwartz (1889–1960), founder-actor-manager of New York’s Yiddish Art Theater, asked Aaron Zeitlin to come from Warsaw to collaborate on a production of his play Esterke un Kazimir der groyse (Esterke and Casimir the Great) in 1939, neither man knew that this invitation would save the life of the playwright, who arrived in the U.S. just before Germany invaded Poland. The Yiddish Art Theater, which opened its doors in 1918, was the most prominent of the companies performing in Yiddish in New York after World War One.11 Despite constant financial struggles, it maintained its commitment to the agenda of Yiddish “art theater” as articulated in Schwartz’s high-minded manifesto, which appeared in Forverts in 1918 and insisted that the theater “must always be sort of a holy place, where a festive and artistic atmosphere should reign.”12

In addition, this manifesto insisted that “the author should also have something to say about the play,” so it is not surprising that Zeitlin had been invited to visit.13 Nor was he unknown to the patrons and devotees of the Yiddish Art Theater on Second Avenue. His piece Khelemer khakhomim, which was based on a more sophisticated earlier version, Di Khelemer komediye (The Chelm comedy), had been given its premiere there on October 16, 1933.14

At that time, Zeitlin was still living in Warsaw. Part of a family of writers and thinkers (his father was the Hebrew and Yiddish author Hillel Zeitlin), Aaron Zeitlin wrote poetry and prose in both Yiddish and Hebrew and was the founder and chair of the Warsaw Yiddish PEN club.15 In 1932, he launched Globus, a journal that during its two years of life aspired to publish the most ambitious Yiddish literary writing worldwide. A fellow participant in the enterprise was Isaac Bashevis Singer, who, while serving as secretary of the editorial board, became a close friend of Zeitlin.

When Zeitlin’s Wise Men of Chelm opened in New York, the play was warmly received by the Yiddish and English press alike. The New York Times admired its “genial lunacy,” which, it suggested, “should shrink the distance between Broadway and Second Avenue.”16 The Times was seconded by Edith J. R. Isaacs from Theatre Arts Monthly, who included it in her Broadway review, stating that the play was “worth the world’s attention” with “an Oriental folk quality that is amazing.”17 The Forverts published a detailed synopsis in Yiddish, along with a review by the paper’s legendary editor, Abraham Cahan, expressing his admiration for both the play and the production.18 The Wise Men of Chelm was nevertheless yet another financial flop for the Yiddish Art Theater, which had to shorten its 1933–1934 New York season and start touring the provinces a few weeks earlier than planned, but Zeitlin’s “charming fable” was remembered as the “one artistic success” of the year.19

In the first act of the play, the Angel of Death becomes fed up with his uniquely depressing job. In the next act, he has nevertheless just carried off ten “Broder singers”—eastern European Jewish itinerant entertainers who performed in taverns and public spaces—and brought them back to the heavenly court. At his request, the group’s violinist, Getzele from Chelm, performs a tune, one that he used to play for his fiancée, Temerel, while he was still alive.

Charmed, the angel decides to go down to earth, marry Temerel, and make humankind immortal by discontinuing his work. The angel heads for Chelm disguised as a certain Azriel Deutsch, ostensibly a rich merchant from German-speaking Danzig. The name Deutsch connotes daytsh, the Yiddish equivalent—literally “a German” but used also to mean a modern Jew, one who dressed in German, that is, western European, style.20

Before Azriel arrives on the scene, the audience is treated to dramatizations of a few famous Chelm stories, including the episode of the wagoner with the extralong log, which, lying sideways across his wagon, prevents him from passing down a narrow street. The rabbi of Chelm, Yoysef Loksh (Yosef Noodle), played by Maurice Schwartz himself, comes up with the obvious solution and orders that the houses be torn down—on both sides of the street.

When the outsider Azriel Deutsch arrives with the news that there will be no more death, the announcement is welcomed with joy by the Chelmites but not by the hobgoblin Yekum Purkan, who has been sent down from heaven to get the Angel of Death back to work. Yekum Purkan takes on the form of a yokel and tries to put forward counterarguments but with no success, his appearance making less of an impression than that of the affluent German Jew. Thus, Azriel marries Temerel in the presence of the whole town.

Right after the wedding, the assembled crowd wants to sanctify the new moon, an occasion for a reworking of one of the oldest and best known of Chelm tales. When, in this version, the Chelmites discover that the moon, the reflection of which they had captured in a barrel of wine, has “escaped,” Yekum Purkan, with his otherworldly powers, produces another moon for the rabbi to hold up during the desired blessing. The rabbi lets go of it, however, and off it flies.

Nevertheless, Yekum Purkan is appointed superintendent of the ritual bath. The newlyweds Azriel Deutsch and Temerel move into a new home, but they can find no peace. Every night, hobgoblins and imps, roused by Yekum Purkan, Azriel’s adversary, make a tremendous racket outside the couple’s home—and not only hobgoblins and imps but also desperate beggars no longer receiving from mourners the alms on which they have always depended, since nobody dies and there are no mourners. Women, too, come to demonstrate, incited by Yekum Purkan to feel unfulfilled now that nobody dies and the male impulse to procreate has correspondingly vanished.

Finally, everyone is persuaded to demand that immortality should be abolished. The Angel of Death, saddened by what he recognizes as “the incorrigible folly of mankind,” regretfully agrees to resume his duties.21 He returns to heaven, taking Temerel with him. Tried for desertion, he is acquitted through an oversight, but Temerel is sent back to Chelm to be united with Getzele’s brother, Yossele, her rightful partner according to the biblical law of levirate marriage, according to which the brother of a deceased married but childless man is obliged to marry his widow.

Zeitlin’s play is unique in the Chelm literature, which was and remains generally devoid both of love stories and of heavenly interventions, let alone stories of a populous spirit world, aside from the angel with the bag of foolish souls in the mythical account of Chelm’s foundation. In contrast, the cosmos that Zeitlin creates around Chelm is filled with angels and fairies. Interviewed by the Literarishe bleter in 1933, he described his play as an encounter of a worldly Chelmishness with the supernatural world—“folksy-fantastic, playful-grotesque, with transitions from the comical to the uncanny and vice versa.”22 It matches the mood of a letter he wrote to the Yiddishist literary critic Shmuel Niger (1883–1955) in 1934, stating that the “heavenly world” was “the only reality” and was “found not only in heaven but also in the mundane world.”23

There is clearly a point of contact here with the neo-Hasidism to which the playwright’s illustrious father, Hillel Zeitlin, had become devoted, and the play resonates with echoes of European and classical Greek drama as well as the Chelm-tale repertoire. Regarding its metaphysical character, however, one precursor stands out more than others: “Der Khelemer melamed” (The teacher of Chelm, 1889), a short story by Yitskhok-Leyb Peretz (1852–1915), in which the disappearance of the yeytser hore, the “evil inclination,” spells an end to procreation, and consequently humanity, just as the disappearance of death does in Zeitlin’s play.24 Both conclude that only a flawed humanity is viable, one infected with folly in the widest sense of that term.

When the play opened on Second Avenue in 1933, only a handful of homegrown publications, all in Yiddish, among them A. D. Oguz’s story “A khokhme fun Khelemer kahal” (A piece of wisdom from the community of Chelm, 1911), B. Alkvit’s “A mayse mit a shteyn” (A story with a stone, 1925),25 and Ben Mordekhai’s 1929 collection of Chelm stories,26 were available to clue in theatergoers.27 Most members of this audience had emigrated from Europe before the Chelm boom of the 1920s or had been born in the U.S. and therefore likely knew nothing of the town’s burgeoning reputation.28

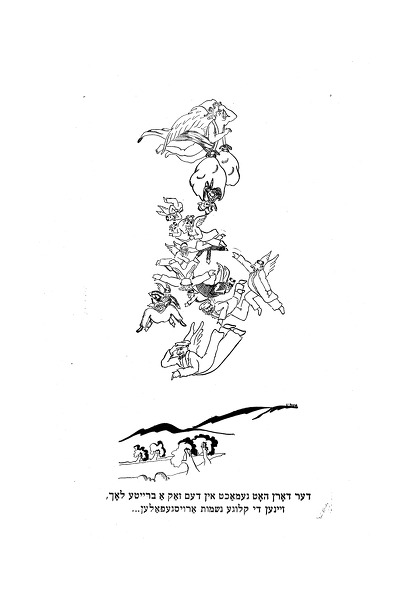

Birth of Chelm, from Ben Mordekhai, Khelmer naronim: Geklibene mayselekh (New York: Hebrew Publishing Company, 1929)

In addition, the Yiddish Art Theater of 1930s New York had a following among people with only a limited facility with the Yiddish language. For their benefit, the company supplied detailed English synopses for its productions. This is fortunate, because the never-published manuscripts of Zeitlin’s play are believed to be lost, so that knowledge of its content must be gleaned from reviews, the Yiddish summary printed in Forverts, and the playbill preserved at YIVO, which includes the English-language synopsis.29

This synopsis was prepared by Maximilian Hurwitz, who, in his introduction, compares the prevailing spirit of Chelm to the “stupidity which English folklore ascribes to the inhabitants of the village of Gotham, in Nottinghamshire, England.”30 He explains that “the simplicity of the Chelmers and their prodigious feats of folly are celebrated in song and story, wherein the East European Jew gives free rein to his genius for mythmaking and racy, Rabelaisian humor.”31 From this, one can infer how little New Yorkers knew of literary or folkloric Chelm and also how established a cultural tradition it was thought to be in Jewish eastern Europe.

It was customary for New York–based Yiddish theater companies to play a winter season in Buenos Aires. Thus, in October 1957, twenty-four years after the New York production of Aaron Zeitlin’s play, Maurice Schwartz revived Jelemer Jajomim at the Teatro Argentino to great acclaim, with Schwartz and his adopted daughter, Frances, singled out for their acting.32

Yankev Botashanski’s review in the Buenos Aires Yiddish newspaper Di prese makes clear that the audience there required no priming to know what Chelm connoted. They were predisposed to laugh at the first hint of a familiar story, although, as Botashanski noted, the work turned out to be “not a play about Chelm folklore,” as he and his fellow audience members knew it, but rather a “fantastic story” that exploits or builds on the old Chelm tales.33

What accounts for the apparently differing level of Chelm consciousness between New York and Buenos Aires Yiddish theater audiences? Had the eastern Europeans who emigrated to Argentina been better versed in Jewish culture or folklore? There is no reason to think so. Were the Jews of 1957 Buenos Aires less assimilated than the Jews of 1933 New York? Not necessarily. Instead, the main factor was almost certainly the passage of time. Between the early 1930s and the late 1950s, Chelm had the chance to penetrate the entire Yiddish Diaspora, spread by word of mouth and various printed formats, perhaps the most important among them being the 1951 novel Khelemer khakhomim, by the New York–based Y. Y. Trunk, published only in Buenos Aires.34

Books on Chelm aside, anthologies of Jewish humor would often feature a section on Chelm. Many collections previously published in Europe were reissued in New York, including the compendium of Yiddish jokes collected by the distinguished editor Yoshue Khone (Yehoshua Ḥana) Ravnitski (1859–1944) and originally published in Frankfurt in 1922, which appeared in expanded form in New York in 1950.35

Among other postwar anthologies of Jewish humor or Jewish writing that include Chelm stories are Jacob Richman’s Jewish Wit and Wisdom (1952) and Naftoli Gross’s Mayselekh un mesholim (Tales and parables, 1955).36 One of the most successful English-language anthologies to feature Chelm tales was the Treasury of Jewish Folklore compiled by Nathan Ausubel (1898–1986), which appeared for the first time in 1948, reappeared in more than twenty printings, and contributed greatly to the development of another Chelm play, The World of Sholom Aleichem, which played a major role in introducing Chelm to America.

Arnold Perl’s World of Sholom Aleichem opened in Manhattan on May 1, 1953.37 It became an Off-Broadway hit, selling out its original run and playing for an additional nine months starting in September of that year. According to Commentary, “for several months now, New Yorkers in large numbers have been flocking to the Barbizon Theater,” where the typical customer would “as often as not . . . buy four, five, or six tickets, inviting his parents to come along and bringing the children as well: The World of Sholom Aleichem has found an audience suddenly eager to discover a bond of community in reminiscences of the bygone Jewish world of nineteenth-century Eastern Europe.”38 The influential theater critic of the New York Times, Brooks Atkinson, called the work “humane, wise and delightful.”39 The play was subsequently performed all over the U.S. and in Argentina, Great Britain, and South Africa.40

That the production became such a triumph was not something that could have been predicted. Perl (1914–1971), an American-born Jew who had seen the Dachau concentration camp as a soldier and became increasingly interested in Jewish culture after the war, found himself mentioned in Red Channels: Report of Communist Influence in Radio and Television and was blacklisted in 1950.41 Having lost the writing commissions on which he depended, he teamed up to form the independent Rachel Productions with the actor Howard da Silva (1909–1986), who had been blacklisted after a summons to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee.

The World of Sholom Aleichem was the team’s first endeavor, and they employed a whole cast of blacklisted actors, including such theatrical eminences as Morris Carnovsky and Ruby Dee; the casting of the African American Dee as an angel was enough to cause a little frisson all its own.42 The audience, as the press agent Merle Debuskey remembers it, was made up of two demographics: “the left, the progressives,” and “the people who knew and loved Sholem Aleichem.”43

The play was criticized in some quarters for its blatant politics, and it is hard to disagree with Midge Decter’s view, expressed powerfully in Commentary, that the sense it conveyed of Sholem Aleichem’s world was partial, simplistic, and idealized. Nevertheless, the production took the milieu of Yiddish literature and literary topics to an English-speaking mass audience, somewhere it can scarcely be said to have gone before.44

That breakthrough was ensured not just by the play’s success in theaters but also by the broadcast of a filmed performance on December 14, 1959, as part of the first season of Play of the Week, a prestigious showcase of the “golden age of television.” Sound recordings of the play, distributed by Rachel Productions and Tikva Productions, sold widely through the 1950s and into the 1960s. The play was also appealing because of the way it translated Yiddish culture into English. Encouraged by this success, Perl went on to write more plays set in an imagined eastern Europe, among them his 1957 Sholem Aleichem adaptation Tevya and His Daughters.

Perl’s play took its title, though little else, from Maurice Samuel’s book The World of Sholom Aleichem (1943).45 In fact, just one and a half of the three one-act plays that make up the entertainment have anything to do with Sholem Aleichem. While the last part of the “triptych,” titled “The Gymnasium” (in the European sense of the word gymnasium: high school), is based on a story by Sholem Aleichem, the text adapted for the centerpiece of The World of Sholom Aleichem, “Bontshe Shvayg,” is not his at all but one of the best-known stories of Y. L. Peretz.46 The first act, or play, of the three is titled “A Tale of Chelm” and is announced as a “forspeiss,” one of the few Yiddish words in the script, which makes sure to translate it (as “a preview, a sample”).47

The first act begins by staging a few elements of the existing Chelm repertoire to set the tone, much as Aaron Zeitlin had. Then it segues into new material, or, rather, old jokes newly applied to Chelm, and then moves on to the pièce de résistance, a story by Sholem Aleichem about a fool who could easily have been a fool of Chelm but is not, Sholem Aleichem having preferred to invent his own fictitious location for the occasion. Because the folly involved is so much like the folly in the Chelm tales and because Chelm had, in the intervening years, acquired a monopoly on Jewish folly, Perl, or rather Perl’s immediate source, Ausubel, overrides Sholem Aleichem’s choice and makes it a Chelm tale, the “Tale of Chelm” of the piece’s title.

The rationale for combining these three pieces and presenting them in this order, da Silva wrote in the “production notes,” was to convey the idea of progression: “Chelm tries to laugh oppression away; Bontche gently condemns it; Gymnasium begins to combat it.”48 The play ends with an appeal to strike and in the last scene declares, “This is the dawn of a new day. No more pogroms, no ghettos, no quotas. Education is free! In this fine new world, there will be no Jews, no gentiles, no rich, no poor, no underdogs and no undercats.”49

The play opens with the appearance not of Sholem Aleichem but of Mendele Moykher-Sforim, Mendele the Book Peddler. This is the pen name and fictional persona assumed by Sholem Aleichem’s mentor, the Yiddish and Hebrew writer Sholem Yankev Abramovitsh (1835–1917). But it is not as a creative genius that Howard da Silva comes onto the stage but merely as an unsophisticated book peddler, pushcart in hand, an homage that a withering Midge Decter calls “lèse-majesté.”50

Mendele, picking up books from his cart as ostensible aides-mémoire, serves as the play’s narrator and commentator. He introduces “The Chelm Story” as “a folk story,” explaining that Sholem Aleichem had gotten the idea from the people “like all great artists,” before launching into the action with a rhetorical question: “What, you ask, is Chelm; or, if you know that it is a famous city in the Old Country, what’s so special about Chelm? I’ll tell you.”51 The angel with the bag who dropped the foolish souls over Chelm appears onstage and tells of his mishap. Then, to illustrate the consequences, there follows the old story of how the Chelmites carry the tree trunks they need for construction down the hill before a visitor from Lithuania shows up and tells them how easy it is to roll logs downhill instead of carrying them, whereupon, suitably impressed, they heave the trunks back up to the top and let them roll down.

After this introduction to the people of Chelm, Mendele presents the wisdom of individual inhabitants such as Rabbi David, who declared that “from now on every poor man will eat cream and every rich man will drink sour milk,” his means of effecting this change being his decree that “from now on sour milk is called cream and cream is called sour milk.”52 The rabbi also has answers to such questions as what makes the sea salty (answer: the many herrings that inhabit it).53

Next up is the proverbially poor melamed, the teacher, who daydreams of becoming as rich as the tsar. No, he would be richer, since he “would do a little teaching on side.”54 Sent out to buy a chicken, he notes that the poulterer praises the chicken as fat, so, with impeccable Chelm logic, he decides to buy not a fat chicken but fat itself—except that he hears the fat praised as being as good as oil, so he decides to buy oil, only to change his mind again when the oil is acclaimed as being pure as water, a pitcher of which he brings home to his wife. Not that she is in much of a position to complain about faulty reasoning: according to her, two times seven is eleven, a fact she knows from personal experience. When she married the teacher, she had four children from a previous marriage, and he had four as well. Together, they had three more children. Thus, she has seven children, and he has seven children, which does indeed make eleven.

Some of this material is drawn from Chelm tales previously published in Yiddish and, to a greater extent, English.55 Most of the stories appear to come from the English version of Solomon Simon’s Wise Men of Helm and Their Merry Tales (1945). Also incorporated are jokes and conundrums drawn from American culture and here attributed to Chelm. This mix of Yiddish and American popular cultures, of the familiar and the unfamiliar, but the not too unfamiliar, must have appealed to the variously mixed audiences that the play attracted. Perl, not religiously inclined himself, omits any stories that presuppose even minimal knowledge of Jewish practice. Any particular eastern European Jewish flavor that remained was accessible enough not to clash with the broad claims that the play staked on behalf of oppressed simple people generally.

The climax of Perl’s “Tale of Chelm” is the teacher’s attempt to buy a nanny goat, which Mendele introduces as a story by Sholem Aleichem. Though Sholem Aleichem, born Sholem Rabinovitsh (1859–1916), never wrote a Chelm tale, he did write the tale that Perl now retells, and the association of this tale with Chelm is not new. In a 1929 essay, no less discerning a figure than Itsik Manger (1901–1969) stated his conviction that Sholem Aleichem “built his masterpiece ‘The enchanted tailor’ on one of the Chelm anecdotes.”56

Sholem Aleichem’s “Der farkishefter shnayder” (The enchanted tailor) is one of his longer stories, first published under the title “Mayse on an ek” (Story without an end) in 1901.57 He based it on “Oyzer Tsinkes un di tsig” (Oyzer Tsinkes and the goat), a tale by Ayzik Meyer Dik (1807/1814–1893), which Dik published in 1868 in one of his many ephemeral booklets of such stories, which sold in great numbers.58

The protagonist, Oyzer Tsinkes, is a melamed (teacher) in Abdezirisok, an imaginary place whose name almost certainly alludes to the ancient Greek foolish town of Abdera.59 Dik’s locale is reworked and expanded by Sholem Aleichem into a fireworks display of fictitious place names. The protagonist—a tailor, not a teacher—is said to have “lived in Zlodievke, a shtetl near Mazepevke, not far from Khaplapovitsh and Kozodoyevke, between Yampoli and Strishtsh, right on the road that goes from Pishi-Yabede through Petshi-Khvost to Tetrevits and from there to Yehupets.”60

The poor man, whose combined piety and simplicity is suggested by the frequent addition to his speech of Aramaisms and nonsense, is sent by his wife to buy a goat in nearby Kozodoyevke (“Goatsville”). On his way home with the creature he has bought from a melamed there, he stops at an inn, where Dodi, the prankster innkeeper, secretly substitutes a billy goat for the tailor’s nanny goat.

The tailor’s wife realizes that there is a problem when she goes to milk the animal, and so the tailor is sent back to Kozodoyevke. Each time he passes the inn, however, he stops for refreshment, and each time Dodi switches the goat for one of the opposite sex. Finally, it is all too much for the tailor, who is last seen in bed, fighting the Angel of Death. The narrator declines to report the end of the story, since it was a “very sad one.” He prefers “lakhndike mayses” (funny stories) and hates stories with a moral.61

Among the most widely read English versions of Sholem Aleichem’s story was its retelling as a Chelm tale in Nathan Ausubel’s “The Chelm Goat Mystery,” one of twenty-four putative Chelm tales in his Treasury of Jewish Folklore.62 Referencing Sholem Aleichem and his English translators Julius and Frances Butwin in a footnote, Ausubel’s version blends the “enchanted tailor” with “legitimate” Chelm, one of two stories published in Menakhem Kipnis’s Khelemer mayses (1930) that tell of how Chelmites were induced to buy less valuable male animals instead of milk-giving females, with the inability to differentiate between the sexes illustrating admirably the foolishness of the townspeople.

One of these stories tells how the rabbi fell sick and was advised to buy a nanny goat to drink its milk. His shammes (assistant) goes off to a livestock market, where a peasant, realizing that he is dealing with a customer from Chelm, sells him a billy goat for the price of a nanny. When the shammes returns, everyone in Chelm is required to bring a plank from his floor to build a barn for this creature, which is expected to save the rabbi’s life. But when the rabbi’s wife enters the barn and attempts to milk the goat, the billy, understandably, kicks at her violently.

The Chelmites come up with a solution for the goat’s puzzling behavior: the rabbi’s wife should dress like a Gentile farmer’s wife so the creature will feel at home. She does, but the billy kicks her again; and the same thing happens when the rabbi, dressed as a Gentile farmer, tries his hand at the feat. Finally, the Chelmites tie the rabbi to the billy goat and try to hold the animal still by its horns, but to no avail. On the contrary, the desperate goat tears off, pulling the rabbi with him and not stopping until it reaches Bukovina.

In Ausubel’s version, which merges Sholem Aleichem and Kipnis and is told with an anti-Hasidic undertone, it is a Hasidic rebbe who falls sick, and his Hasidim who get the nanny goat, which is repeatedly exchanged by the malicious innkeeper because he has “a hearty dislike for wonder-working rabbis.”63 After much toing and froing, the Hasidim finally return with a certificate from the rabbi of the goat vendor’s village, guaranteeing the animal’s female credentials, plus a goat that, having been exchanged once again by the innkeeper, is, once again, male. At this point, the rabbi of Chelm invokes mystical pseudoscience to explain the inexplicable. It is “the confounded luck of us Chelm schlimazls, that by the time a nanny goat finally reaches our town, it’s sure to turn into a billy.”64

Perl uses Ausubel’s punch line and other material from his Chelmified version, but he also makes use of material from the Butwins’ translation of Sholem Aleichem, reintroducing details from the Chelm-free story into his script. Thus, Perl’s protagonist is a teacher (like Dik’s and unlike Ausubel’s rabbi and Sholem Aleichem’s tailor) but goes to a town “famous for its goats” and is victimized by an innkeeper called Dodi, both of which details accord with the Butwins’ Sholem Aleichem version.65

Much of the credit for the effectiveness of the sketch was due to the superior abilities of the play’s director, the celebrated acting teacher Don Richardson, and the blacklisted actor who played the befuddled melamed, Tevye-in-training Zero Mostel. Mostel’s weary journeyings across the stage with the goat, or rather with just a rope, an unseen imaginary goat at the end of which drags him back and forth, are described by Atkinson in the Times as “the most humorous element in the sketch,” a kind of dance that he considers at once “lyrical” and “imbecilic” and sufficient to convey “the foolishness of Chelm, where the people are not very bright.”66

Midge Decter in Commentary would have agreed with the word “imbecilic” even if she did not see the “lyrical.” For her, that world was only “the kind of Never-Never Land American Jews like to think they come from.”67 Regardless, the play broke new ground, introducing eastern European Jewish popular culture to a generation of deeply Americanized Jews and to the American mainstream. And Arnold Perl must bear all the responsibility for the persistent but entirely erroneous belief that Sholem Aleichem ever wrote anything at all about Chelm.

The First Novel: Yekhiel Yeshaye Trunk’s Jews from the Wisest Town in the World

One of the first scholarly evaluations of Sholem Aleichem’s oeuvre was produced by Yekhiel Yeshaye Trunk in 1937. In Sholem-Aleykhem: Zayn vezn un zayne verk (Sholem Aleichem: His essence and his works), Trunk states that the one who wears the “little jingly fools-cap and the colorful dress of the comedian” also bears the “cup of knowledge” and that “the great masters of comedy,” among whom he numbered his subject alongside Cervantes, Shakespeare, and Gogol, “had almost always the will to transform the fool (lets) into the transmitter of the world’s profoundest wisdom.”68

This perception also underpins Trunk’s major work of fiction, his Khelemer khakhomim oder yidn fun der kligster shtot in der velt (The wise men of Chelm, or, Jews of the wisest town in the world), published in Buenos Aires in 1951. The intervening years had seen the annihilation of the Polish Jewish culture in whose worth he believed so completely and his own escape through Vilna (Vilnius) and across the Soviet Union to Japan and on to New York, where he settled in the Washington Heights section of Upper Manhattan in 1941.69

Born in 1888 in Łowicz, west of Warsaw, Trunk was educated in religious and secular subjects by private tutors in Łódź, where his family settled when he was six years old and where he grew up in a privileged milieu of mercantile wealth from his mother’s side and Jewish learning from his father’s, his paternal grandfather, Israel Joshua Trunk of Kutno, having been one of the most highly esteemed Polish rabbinic authorities of his time.

Trunk started writing poetry in Hebrew but changed to Yiddish in 1908 after meeting Y. L. Peretz, who urged him to switch allegiance. Affluent and very much a member of the elite, Trunk nevertheless sympathized with socialist ideas and joined the Bund in 1923.70 He moved to Warsaw in 1925, remaining there until the German invasion of Poland in 1939. On arriving in the United States, he began work on his monumental memoir, Poyln: Zikhroynes un bilder (Poland: Reminiscences and images), published in seven volumes between 1944 and 1953. It is the memoir and his book on Chelm that represent his most important contributions to Yiddish literature.

Trunk considered Jewish history merely “a loyze zamlung fun farshidene geshikhtes” (a loose collection of diverse histories), with these diverse histories separated largely by language.71 As such, he believed strongly in a Yiddish nation, a concept perhaps more meaningful to him than that of a Jewish nation. Although neither Polish Jewry nor the Yiddish nation could, without a stretch, be said to have survived the Holocaust, Trunk continued to write in Yiddish and on the Polish Jewish experience, evidently, above all, as an act of commemoration.72

Trunk’s Khelemer khakhomim is the first full-scale novel to be written about Chelm. The work, an episodic novel but one with recurrent figures, consists of seventeen stories, each divided into multiple chapters. His subtitle, Mayses fun dem Khelemer pinkes, vos men hot nisht lang tsurik gefunen oyf a boydem fun a mikve (Stories from the record book of Chelm, found not long ago in the attic of a mikveh), reflects his desire to evoke a ruined past. The record books (pinkasim) maintained by European Jewish communities since the Middle Ages were official manuscript volumes containing registers of events, transactions, minutes of meetings, and judicial deliberations. An old pinkes of Chelm, therefore, would be the most authoritative source for the history of this, or any, Polish Jewish community.73

But Trunk’s conception of Chelm both does and does not treat the place as akin to any other Polish Jewish community. Chelm is at once singular and universal, the paradigm for all Polish Jewish communities and all communities of whatever kind anywhere. As Trunk writes in his preface, “Khelm iz dos moshl fun der velt” (Chelm is a parable for the world).74 In saying this, he sets out a universalizing agenda much like that of the folly literature of the late medieval and early modern period.

Trunk’s Khelemer khakhomim resembles the European tradition of folly literature in other respects, too. The narrator often addresses the reader directly with comments on the material he is, supposedly, only transmitting, and, again as in earlier folly literature, Trunk’s narrator proves to be “unreliable,” presenting readers with conflicting information and going out of his way to mislead them.75

Thus, purely to disorient the reader, Chelm’s origin is described in the second chapter of the book, not the first. Similarly, in relating the best known of all Chelm stories, the attempt to capture the waxing moon in a barrel of water, the narrator injects novelty into his telling by suppressing the familiar rationale for the attempt, that is, to enable the monthly ritual “sanctification” of the new moon, even when clouds keep it from being seen. To the contrary, Trunk insists perversely that the pinkes provides no justification for the Chelmites’ inexplicable endeavor.

Elsewhere, the narrator claims that vital pages are missing from the manuscript because it has been consulted too often, so that the nature of the quarrel between Reb Yoysef Loksh (Yosef Noodle) and his wife must remain unknown forever.76 In the case of another marital dispute, the narrator expresses his mistrust of the pinkes and contends that the alleged violent behavior of the couple may be overstated.77 All these asides create an ambiguous account, a characteristic trait of folly literature.

For Trunk, the lover of Poland, Chelm, a city founded just after the week of divine creation, is the center of the world. He is emphatic that Adam attended the synagogue of Chelm and was a Polish Jew, definitely not a Litvak, a Lithuanian Jew. Moreover, according to his alleged source, a Chelmite is said to have served as the kvater (godfather) of Methuselah. Chelm’s history takes precedence over other narratives in Jewish history, such as the Pentateuchal narrative of enslavement in and deliverance from Egypt.78 The time frame for Chelm Jewish history in Trunk’s tales is all-encompassing; distinguished visitors to the town range from Og, King of Bashan, last of the primeval giants, to Albert Einstein.

Trunk’s Chelm is located in a fictionalized Poland, a monarchy whose king timelessly has his seat in Warsaw. His Chelm is an entirely Jewish town, or, rather it has one non-Jewish inhabitant, the Shabbes goy, who also serves as the bathhouse attendant. However, in another sign of a topsy-turvy world, when the Chelmites decide to emulate Warsaw and have a resident king, they end up electing the only Gentile in town, despite (or because of) his ignorance and habitual drunkenness.

Here Trunk has skillfully changed many aspects of a previously known Chelm tale, in which the Chelmites elect one of their coreligionists king.79 Trunk also adds many new twists to other previously known stories. According to him, the quarrel between the teacher and his wife is inspired by the yeytser hore, the “evil inclination,” to which he attributes a transcendent substantive reality. The yeytser hore adds fuel to the fire at every opportunity, feeling satisfied only when the dispute turns violent.80

According to Trunk, Chelm’s reputation for wisdom was so great that it became the model for all the predominantly Jewish shtetlekh (towns) in Poland. Thus, Chelm’s streets were unpaved, and the whole place was awash with blotes (mud) when it rained. Its wise men celebrated the situation on the grounds that the town should look just as it did at the time of Creation, when there was only wisdom in the world (and not paving). Trunk claims that it was out of deference for Chelm’s preeminent wisdom that every other shtetl in Poland remained unpaved and drowning in mud.

Not only are Trunk’s Chelmites looked up to by other Polish Jews, but their self-confidence is such that they look down on the rest of the world as foolish, more or less so depending on how different any given place is from Chelm. Two Chelmites, Reb Fayvush and Reb Leybush, decide to profit from the folly of other lands and set off “opnarn di narishe velt” (to mock the foolish world) and “ontun a spodik”—to put on it a spodik, a fur hat doing duty here as a fool’s cap.81

They come first to Prussia, in the land of the “yekishn keyser” (the German emperor). Trunk intimates how far out of their depth Fayvush and Leybush are by having them describe the kaiser as yekish, Yiddish slang for German Jewish, not simply German.82 The Chelmites’ confusion between German Jews and non-Jews is exacerbated by the bewildering language that everyone, Jewish or not, speaks in Prussia, a language that “iz nisht yidish un nisht goyish,” is not Jewish but not Gentile, that is, not Slavic.83

In a masterstroke of inversion, Trunk has his Chelmites believe that the touchstone of people’s Jewishness is the degree to which their speech resembles that of Polish Jewry. In such a system, Gentile speakers of German are “more Jewish” than Gentile speakers of Slavic languages, Standard German being, from the Chelmite point of view, a corrupted form of Yiddish. Fayvush and Leybush can hardly believe how strange and foolish their new surroundings are. Even the houses in Germany are “oysgeputst un oysgeshleyert vi kales tsu der khupe” (dressed up and veiled like brides for a wedding), although with their red roofs they look more like “narishe indikes” (ridiculous turkeys).84

Arriving in the Prussian city of “Giml,” they conclude that they have just crossed the legendary river Sambatyon into the land of the mythical “Red Jews,” and they cannot understand why they can see no sign of yidishkayt.85 By now starving, the pair pretends to be blind and beg on the streets for money, not humbled but, as true Chelmites, proud and excited to be mocking the foolish world.

The outside world also tries to fool Chelmites on their home turf. In one episode, an Erets-Yisroel yid (a Jew from the land of Israel) arrives in town, dressed in a white silk kaftan, a white yarmulke, and a crumpled fur hat, and insisting he can speak only zoyer-loshn (the language of the Zohar), the arcane Neo-Aramaic coined for medieval Jewish mysticism. These accoutrements ought to, but do not, scream the word “impostor.”86 This Jew, professedly from the land of Israel, is trying to sell land-of-Israel prayer shawls as well as phylacteries in bags made from velvet that once covered the tombs of the matriarch Rachel and the talmudic sages Rabbi Ammi and Rabbi Assi.

Reb Yoysef Loksh makes a brave attempt to converse with this man in half Hebrew, half Aramaic, and asks, of all things, whether the Turks, among whom the Erets-Yisroel yid lives, are the most foolish Gentiles in the world. Wonder of wonders, the holy man from the Holy Land forgets himself and answers in mame-loshn (the vernacular, Yiddish), declaring that the Turks have chosen Ishmael for a grandfather and commenting, “A sheyner zeyde der feter Yishmoel! Er tut gornisht, nayert zitst in der midber mit di fis oyf arunter, est semetshkes un shist mit a faylnboygen” (a fine grandfather that is, Uncle Ishmael!87 He does nothing but sit cross-legged on the ground in the desert, eat sunflower seeds, and shoot with a bow).88 Disguised in a story of an imposture, Trunk’s anecdote almost certainly hints at his aloofness toward Zionism and his unhappiness at the unnatural use of Hebrew and not Yiddish as the national language of a Jewish homeland.89

In addition to Fayvush, Leybush, and Yoysef Loksh, the parnes (lay leader) of the community, there are other recurrent characters in Trunk’s Khelemer khakhomim, among them Khoyzek, the town fool, who would supposedly be reckoned a sage in any other town.90 Trunk’s Khoyzek sleeps outdoors in the market place next to the well, and he goes about in broad daylight holding a lit lantern and beating a kettledrum given him by the town’s klezmorim (musicians).

Trunk, who was well acquainted with European literature, blends the traditional Jewish foolish figure of Khoyzek, associated with Chelm from early on, with the ancient philosopher and ascetic Diogenes, who rejects society’s norms and chooses to act the fool and who is depicted in classical literature carrying a lantern at midday in search of a real man.91 But while Diogenes fails to find even one real man in ancient Athens, Khoyzek has no such problem in Chelm.

How come the Chelmites are of such exceptional caliber? In Trunk’s telling of the etiological story of the angel whose bag of souls broke as he was flying over Chelm, it was not foolish souls that descended on that spot but quite the opposite. The angel was carrying not one but three bags of souls: one bag of pure fools, one bag of wise souls, and one bag containing the wisest of the wise. It was the last of these that dropped over Chelm, and this is how it came to be the wisest town on earth.

Trunk’s Chelmites are unfailingly aware of their wisdom. When Chelm issues invitations to a world congress of sages (“khakhomim-kongres”), many of the most important figures in Jewish folly literature show up, among them Hershele Ostropoler and Efroyim Greydiker, two of the best-known fools in Yiddish folklore.92 Joining them as the keynote speaker at the conference banquet is Albert Einstein, who pays handsome tribute to the wisdom of Chelm. “I look at the stars,” he says to his hosts, “and I conclude that all the wheels of the world only appear to turn. All is but Purim-shpil and illusion. Time is a simplistic concept; on every star it babbles in a different tongue. Those who say two and two make four do not know what they are talking about.”93 Abolishing rigid distinctions of time, place, and language, Einstein becomes, as it were, an honorary Chelmite.

“Then,” Trunk writes, “Einstein began to speak just like Reb Fayvke the Litvak: ‘There is no world of here and now—that is what too few educated people understand. Yet I have heard tell that this is what you grasp, children as well as adults, here in Chelm. That is how you managed to capture the moon in a barrel. And that is why I . . . have come here to see for myself.’”94

Trunk ends his book with Hershele placing a yarmulke on Einstein’s head and offering him water for the ritual purification of his hands. The great scientist is identified with the Chelmites, and implicitly, imaginary Chelm has a future, the physical destruction of Chelm Jewry notwithstanding.

Trunk was well acquainted with the Chelm stories published during and after World War One. He knew the people who collected Chelm material, such as Kipnis, and he worked briefly alongside Noah Pryłucki (1882–1941) in Vilna upon his escape from Poland.95 He used previously published stories, retelling and often altering them, as well as inventing entirely new stories.

Though Trunk’s is one the most elaborate and sophisticated of all treatments of Chelm, the work’s content is little known, never having been translated into English or any other language. The same obscurity hangs over many other works of Chelm literature in Yiddish, such as the 1944 epic poem Yosl Loksh fun Khelem (Yosl Loksh of Chelm) by Yankev Glatshteyn (1896–1971).

After World War Two, more and more Chelm books were written in English. The Yiddish educator, writer, and dentist Solomon Simon (1895–1970) published his first book of Chelm stories, Di heldn fun Khelm, largely based on Kipnis’s output, in 1942, hoping that it would serve as a vehicle for teaching Yiddish. A heavily edited version of this collection appeared in English in 1945 as The Wise Men of Helm and Their Merry Tales. Translated by Simon’s son David Simon and Ben Bengal, it included a completely new opening chapter with a sequence of Chelm jokes in an almost Vaudevillian style, and it became the first widely known book-length work of English Chelm literature.96 Pearl Kazin, writing in Commentary, praised it as a “parable of all Jews living in a world that is stupid and powerful. Their intelligence is materially fruitless, and their ingenuity brings no herring for their potatoes.”97 Simon ends The Wise Men of Helm and Their Merry Tales with the story of the destruction of Chelm and the dispersal of the Chelmites around the globe, where they “mingled with all the people of the world and dutifully spread the wisdom that was once the pride of Helm alone.”98

In 1965, Simon published a second collection, titled More Wise Men of Helm and Their Merry Tales. This version was published only in English and was much more Americanized than its precursor was, even to the point of featuring the River Shore Club, “the oldest and most exclusive club in Helm.”99 Most of Simon’s works, however, he published in Yiddish, editing also the New York–based Yiddish Kinder zshurnal (Children’s journal) from 1948 to 1951.100 Turning to Argentina as one of the largest communities of young Yiddish readers at the time, Simon published a collection of international folktales titled Khakhomim, akshonim un naronim: Mayses fun alerley felker (Wise men, stubborn men, and fools: Stories of many peoples) in Buenos Aires in 1959. The book included three Chelm stories, and Simon stressed in his introduction the shared roots of humankind, reflected in similar stories told all over the world. Chelm serves as just such a transcultural example, since two of his stories are introduced as an “indishe Khelem-mayse” (Indian Chelm story).101

Simon’s widely read books reflect another trend that began in the 1940s: the adaptation of Chelm stories to serve as children’s literature. Among the many subsequent children’s titles are Samuel Tenenbaum’s Wise Men of Chelm (1965), Steve Sanfield’s Feather Merchants (1991), and several picture books, including The Angel’s Mistake by Francine Prose (1997) and Eric Kimmel’s Jar of Fools (2000).102 But no one involved in the production of this English-language Jewish-foolish children’s literature has been as prominent or influential as Isaac Bashevis Singer.

Cold War and Bedtime Stories: The Multiple Chelms of Isaac Bashevis Singer

Isaac Bashevis Singer is sometimes credited with the invention of Chelm.103 If that is one honor too many for the Nobel laureate, he is nonetheless notable as the best known and one of the most prolific postwar writers of Chelm stories. The foolish town appears in many of his children’s books, obviously in The Fools of Chelm and Their History (1973) but also in his Stories for Children (1984) and in individual stories such as “Dalfunka, Where the Rich Live Forever.” In addition, a recurring character in his writing for children, the hapless Mr. Shlemiel, is often identified as living in Chelm.104

Singer published Chelm stories for children in both Yiddish and English and for adults in Yiddish only. His English-language Chelm children’s stories, published in book-length collections with artwork by such well-known illustrators as Maurice Sendak and Uri Shulevitz, were translated into many languages and adapted for the stage as a play (1974) and a musical (1994), both titled Shlemiel the First.105 By contrast, the Yiddish Chelm stories, one series for adults and another for children, both published in the Forverts newspaper, seem to have passed without comment, except for Khone Shmeruk’s Yiddish article on Singer as children’s writer.106

When Singer arrived in New York in 1935, he was thirty-one.107 His older brother, the Yiddish novelist Israel Joshua Singer (1893–1944), introduced him to Forverts’s editor, Abraham Cahan, and soon he was making his living as a freelance writer for the paper.108 Singer’s contributions to Forverts between 1935 and 1987 number in the thousands, but not until thirty years after arriving in the U.S. did he publish his first Chelm story, “Der narishe khosn un di farbitene fis” (The foolish bridegroom and the switched feet), a retelling of an established Chelm tale, which appeared in Forverts in November 1965 under the Singer pen name Yitskhok Varshavski.109

Four months later, this time under the pseudonym D. Segal, another of the three identities Singer used in part to dilute his ubiquity in the columns of Forverts, he published the first of what was to become a series of sixteen new and unusual Chelm stories, which continued to appear until the spring of 1967.110 These are satires, drawing unmistakable analogies to the global politics and cultural change of the time and tracing Chelm’s development into a dystopia divided against itself.

The series starts with what was evidently meant to be a stand-alone piece titled “Di ‘politishe ekonomye’ fun Khelm” (The “political economy” of Chelm), in which Singer claims to be sharing new evidence unearthed from the archives in Chelm. This evidence consists of an account of capitalism gone wrong and the communist alternative that the Chelmites come up with, wherein money and commerce are abolished, and producers, such as the farmer and the brewer, are told to engage in barter.

When that, too, fails disastrously, a bureaucracy is devised, and government agencies are installed in Chelm to procure and distribute goods. When this fails, the Chelmites gather for seven days and seven nights but cannot agree on how to proceed. One side wants to reintroduce money and reopen the shops (and bars); the other side wants to stick with central planning. As a compromise, they divide the town into two sectors: Chelm of the shops and Chelm of the agencies, with the border patrolled by guards. West Chelmites are soon beset by inflation, while in East Chelm collectivization removes every incentive to exertion. The two Chelms blame each other, build up their armies, and make threatening noises.

Singer’s biographer, Janet Hadda, has said of his work during this period that “as a social critic, Bashevis in Yiddish was harsh and conservative, completely unlike Isaac Bashevis Singer, the apolitical, wryly unworldly creature he was becoming in English. His remarks in Forverts seemed calculated to offend whatever Socialists still remained as readers.”111 While Singer’s Yiddish Chelm series does satirize communism, and such episodes as collectivization and the ensuing famine under Stalin or the erection in 1961 of the Berlin Wall, Singer is also critical of the West—the free market and military adventurism on the right, lax law enforcement on the left—leaving the impression that he is less eager to champion any one side than to voice a pervasive pessimism.112

Singer’s skepticism vis-à-vis all ideologies and the idea of progress itself is evident in a 1968 interview, in which he told Harold Flender of his lifelong certainty that neither “socialism or any other ‘ism’ is going to redeem humanity and create what they call the New Man.”113 The idea of salvation on earth Singer considers absurd; salvation, he says, is “completely a religious idea, and the religious leaders never said we would be saved on this earth.”114

When Singer returned to the Chelm theme in Forverts after a lapse of seven months, again in Yiddish and using the pen name D. Segal, it was to start a run of fifteen additional pieces ridiculing the state of the world, this time even more comprehensively, by the simple expedient of attributing some of its more egregiously silly debates and decisions to Chelm. The first of these pieces about “Chelm, its history, its politics, its different epochs, its economy, its culture” was titled “Der groyser zets un di antshteyung fun Khelm” (The Big Bang and the creation of Chelm).115 A fan of neither religious dogmatists nor dialectical materialists, Singer makes light of the science-versus-religion debate on the origins of the cosmos by reframing it as a debate about the origins of Chelm.

One faction adheres to the “biblicist” theory that “when God made the world, he also made Chelm,” according to which “the Chelmites are, like all people, descendants of Adam.”116 Ranged against them are the scientists of the Chelm Academy, true believers in the theory of the Big Bang, which Singer translates into Yiddish as “der groyser zets.”117 The English term was only coined in the late 1940s and did not catch on widely in English until the 1960s, so his discussion of it was quite au courant.

According to Singer’s description of post–Big Bang conditions, “it was the upper crust of Chelm that cooled first, like in a pot of porridge, where the top grows a cold skin, but inside, when you stick a spoon in, it is still hot.”118 As to the question of how long it took for Chelm to cool off, Singer maintains that it is hard to know, since “there was not a single calendar in Chelm back then, nor a watch.”119 In any case, from a blob in the Chelm River there developed the first fish, then land-based animals, and finally Chelmites. Strange but true, Singer says, “with time, a fish can become a goat, a goat a monkey, and a monkey a man.”120 According to Singer’s imaginary archival sources, the opponents of evolution prevailed in Chelm, and the champions of the Big Bang were incarcerated, until there came a time “when the proponents of the Big Bang were released from prison and those who denied the Big Bang were locked up.”121

Singer’s next target is human history, or the deterministic view of history favored by Marxists, tracing inevitable progress from prehistoric society via feudalism and capitalism to communism. First there came a prehistoric cave-dwelling proto-communist society, which he calls the “Mine-is-Yours-and-Yours-is-Mine epoch.”122 In the next stage, Chelm still operated without money, trading instead in eggs, but this meant that “poverty was particularly bad in winter, when chickens lay fewer eggs or eggs get lost in the snow.”123 Apparently it was in Chelm that a wise man first posed the question “Which came first, the chicken or the egg?”124 To this day, however, the Chelmites have not agreed on the answer.

During this period, too, a man could buy a wife for a goose egg, but in time the bride price rose to the point that a wife cost a cow. It was then that a Chelmite called Faytl, who had but one cow, acquired a wife. Because his bride was an orphan, after the wedding she brought the cow back with her into his possession. Impressed with this result, Faytl continued to buy orphan brides until he had more than a hundred wives. Thanks to this distinction, he became king of Chelm. This meant that he did not have to swat the flies from his head because he had human fly swatters to do the job for him. Nor did he have to hold his pants up with a rope like ordinary Chelmites because he had two servants, one on either side, to perform the task.

Faytl’s rise to power marks Chelm’s transition into the age of feudalism. The new king is encouraged by his courtiers to behave as kings do and wage war against the surrounding small towns and villages. Casting about for a casus belli, the Chelmites hit on the idea of a mission civilisatrice. They declare their rustic neighbors to be uncivilized compared to the relatively urbane, rope-belted Chelmites, because they do not wear pants. War would bring civilization to “the half-wild people out there.”125 That they would also pay tribute to Chelm is, of course, a gratifying byproduct.

The war, however, does not go according to plan. As it drags on and on, Chelm runs short of basic commodities, and, as hardship increases, so does lawlessness, to the point that honest folk become an ever smaller part of the population. The wise men gather to consider how to deal with the now hopelessly inadequate town jail, finally concluding that the only solution is to let all the criminals go free and lock up the few remaining upright citizens for their own protection.126

With victory still eluding the Chelmites, the first of many revolutions takes place.127 Faytl is beheaded, and a certain Dalfn seizes power with the promise of “sholem, frayhayt un briderlikhkayt” (peace, freedom, and brotherhood).128 Autocrats come and go—“Twelve Faytls, seventeen Dalfns, and a long line of Vayzoses”—until political parties with opposing platforms are finally founded.129 One party stands for “Chelm above all else,” while the other proclaims an internationalist agenda.130

In the next phase, Chelm becomes so money obsessed that even theology is reconceived along capitalist lines: “God did not create the world on his own; he just hired heavenly workers and . . . wrote the check.”131 Rampant capitalism leads to so much overproduction that the Chelmites feel compelled to wage another war, this time against the nearby town of Mazl-Borsht, in the hope of coercing their neighbors to buy their surplus goods.

Mazl-Borsht is a fictitious town in the medieval tradition of Cockaigne, a land in which people devote themselves to indolence, eating, and drinking. In Mazl-Borsht, a name that combines mazl (fate, fortune) and borsht (beet soup), food is the only thing people ever think about, and their civic pride stems from the belief that they invented “borsht, sauerkraut, and sour pickles.” They further say that “the first kreplach were cooked in Mazl-Borsht, in the reign of Chickeneater XVIII.”132 Finally, after many setbacks, a mass influx to Chelm of Mazl-Borshter consumers occurs, but things look more promising only for a moment.133

Civil war breaks out between Chelm’s revolutionaries and its reactionaries, resulting in “two Chelms with two governments: two separate communities, occupying separate houses, even separate outhouses.”134 The reactionaries establish White Chelm, the revolutionaries Red Chelm, and Singer piles on the satire with a shovel, as in the case of a certain shoemaker and his family.135 The newly enforced frontier between the two communities passes straight through the shoemaker’s home, leaving the workshop on one side and the kitchen on the other. When barbed wire is run through the house, the shoemaker is forced to live in his workshop, cut off from his family. Eventually, he divorces his wife and remarries, after which the ex-wife and new wife spend their days cursing each other across the barbed wire. The outhouse is in no-man’s-land, and both sides required a passport and a visa to get there. This is especially awkward for people on the Red Chelm side, since the government there does not permit its citizens to travel.

Red Chelm is a one-party state where everyone spies on everyone else, even children on their parents, and dissidents are sent to gulag-like slave-labor camps.136 The prayer book is revised so that all references to God are replaced with references to “Bolvan the First.” But if there is too much law and order in Red Chelm, there may be too little in 1960s White Chelm. Living conditions are better, but crime is rife; criminals are mollycoddled, and nothing is done about those who aid and abet the Reds.137

Singer’s series coincided with the launch of the Cultural Revolution in the People’s Republic of China, and in his sixteenth and last article, he introduces a new enemy, “Mizrakh-Khelm” (East Chelm), which poses a threat to Red and White Chelm alike.138 White Chelm, though, is almost too wrapped up in its own self-destructive behavior to notice. Its army consists exclusively of old women, and its culture, be it theater, music, or literature, is in precipitous decline. “Many authors decided to start their novels at the end and to tell every story backwards,” Singer writes. “A novel would begin with the hero and heroine crying, ‘Finally! This is the happiest moment of our lives!’ Then things would start to get messed up and complications would arise, and so the novel would continue until it ended with the words, ‘On a street in Chelm there lived two neighbors, one with a son and the other with a daughter.’”139 Singer’s view of the 1960s is not a happy one on any front, nor does he see the world—“Chelm”—ever improving: “There will always be a Chelm and Chelm will always have ‘wise men.’”140

Singer’s Chelm satires are almost devoid of Jewish content, with the minor exception of references to Jewish food. Otherwise there is hardly a hint of distinctively Jewish life, and as such, his series might be read as a counterstory to Trunk’s tradition-steeped Khelemer khakhomim. Singer’s mention in his first article of “several documents from the Chelm archive” is likely a conscious allusion to the rediscovered pinkes of Chelm in which Trunk claims to have found his stories.141 In Singer’s version of Chelm, where the time zone is strictly contemporary and the ripped-from-the-headlines action is more squalid-foolish than charming-foolish, there may even be a friendly rebuttal of Trunk’s Chelm and its nostalgic re-creation of an idealized pre-Holocaust Polish Jewish past.142

In 1972, Singer published a second set of Chelm stories in Forverts, under the heading “Nokh vegn di Khelmer khakhomim” (More about the wise men of Chelm). Forverts was still a daily newspaper, and the series appeared in six segments between February 21 and March 3. This time the author used the pen name Yitskhok Bashevis, which he generally reserved for his more literary and less polemical writing, and he added to the series title the subtitle “kinder-mayses” (children’s stories). The tone of these stories, which is established at the outset, promised something quite different from his satirical series. Singer’s Chelm tales for Forverts’s adult Yiddish readers had been highly politicized, thoroughly contemporary, and minimally Jewish, constituting a radical departure from the Chelm literary tradition. By contrast, the Chelm that he began creating for the paper’s young Yiddish readers was neither contemporary nor overtly political and was quite Jewish.

That Singer now seemed intent on retelling traditional Chelm tales with his personal flair was apparent from his first story, subtitled “A fish an azes-ponem” (A shameless fish), which was not fundamentally new.143 It appears in one of the earliest ethnographic collections of Chelm stories, the 1917 issue of Noyekh Prilutskis zamlbikher far yidishn folklor, filologye un kulturgeshikhte (Noah Pryłucki’s compendia of Yiddish folklore, philology, and cultural history).144 Singer might have encountered the story via Pryłucki or via Kipnis’s Chelm series, which appeared in the Warsaw Yiddish daily Haynt in 1922–1923 and later in book form.145 The older versions of the story tell how a prominent citizen of Chelm buys a carp (alive, as one did in those days) for the Sabbath. To carry it home, he tucks the fish, head down, into his shirt, as a result of which the protruding and wriggling tail slaps him across the face. For an assault this serious, the Chelmites sentence the fish to death—by drowning.

Singer’s version is greatly elaborated. It describes at some length the process of buying and preparing fish for the Sabbath in the old country and how a certain poor rabbi’s wife in Chelm, who could only afford the tiny fish called shtinkers, would stretch them with vegetables to feed the whole family. One day, however, Mendel the fisherman presents the rabbi with a fine carp as a token of thanks for freeing him from a curse. The nearsighted rabbi bends down to inspect the gift in the bucket, at which point the carp administers the slap in the face.

Despite the mild-mannered rabbi’s objections that the fish is simply behaving as fish do, the more assertive lay head of the community, Groynem Oks, considers the act a khutspe (an impertinence) and wants the fish tried, convicted, and punished. After considering for seven days and seven nights what to do with “dem khutspedikn fish” (the impertinent fish), Singer’s wise men of Chelm, echoing the original story, agree to the sentence of death by drowning.146 To this, Singer adds a final scene, in which the sages are mortified to see the fish swim away unscathed, but Groynem reassures them that justice has been done: the fish of Chelm must have placed the impudent carp under a “kheyrem”—a ban of excommunication requiring ostracism.147 For why else would the fish swim off to other waters?

Singer similarly elaborates a familiar story in the second of his six new episodes for Forverts, this one subtitled “Der Khelmer barg” (The hill of Chelm), but, thereafter, he abruptly changes tack.148 Instead of continuing to use the European Chelm stories for inspiration, he revisits his own sixteen-part series of 1966–1967, which he sanitizes and abridges into the remaining four installments of his children’s series. Gone from the source material are such unsuitable topics as excessive violence and polygamy. Gone, too, are all obvious allusions to recent events, such as the construction of the Berlin Wall. Most conspicuously absent, however, are the luxuriant descriptions of the original version, as in the section where the process of evolution is described:

Little by little the steam began to settle and become water. It became the Chelm River, which is very famous in the history of Chelm. In the beginning the water was warm. In the Chelm River there were not any carp, or pike, or tench; there were not even any of those little fish that people call stinkers. But when the water got cooler, the first living creature appeared. How did it come to be? The answer is provided for us by Professor Vayzose, a native of Chelm. The sun shone. The banks of the Chelm River turned to mud. Something in the mud started to bubble and stir, and, ever so slowly, a creature came into being. Alas, it was rather an unfortunate creature. It did not have any hands, any feet, any stomach, or any brain. It lay in the mud without even knowing that the mud was mud. The poorest pauper lives in luxury compared to this creature. But everything starts with baby steps. It was from this very creature that Chelm originated. This was the father and the mother of all the people—indeed, all the animals—of Chelm.149

In the children’s version of the tale, all that boils down to this: “Later a river formed in Chelm. It contained many fish, and these were the ancestors of the Chelmites. This may be the reason why the Chelmites love fish, especially gefilte fish.”150 These two sentences, corresponding exactly to the Yiddish children’s version, are quoted from The Fools of Chelm and Their History. This English-language novella for children, which Singer published in 1973, is substantially a translation of the 1972 four-part Yiddish children’s précis of the 1966 original.

Singer’s first Chelm story of any kind, published in Yiddish in Forverts in November 1965, several months before the satires, was translated into English as “The Mixed-Up Feet and the Silly Bridegroom” and was included in his first book for children, Zlateh the Goat and Other Stories (1966). That book was the result of a long-standing request for such a volume from Singer’s friend Elizabeth Shub (1915–2004), daughter of the Yiddish writer Shmuel Niger. Shub, who met Singer shortly after his arrival in New York at her parents’ literary salon, worked as a reader in the children’s department of a series of publishing firms and cotranslated Zlateh with the author.151

This English-language book, preceding Singer’s Yiddish Chelm tales for children by six years, contains seven stories, three of which are set in Chelm, a sign of the importance of the place in the writer’s mental geography.152 Chelm went on to serve as a location for Singer’s English writing for children in three additional stories in When Shlemiel Went to Warsaw and Other Stories (1968), The Fools of Chelm and Their History (1973), and three stories in Naftali the Storyteller and His Horse, Sus, and Other Stories (1976), one of which had been published previously in Cricket and another in the New York Times.153

Cricket was launched in September 1973 with the hope of creating something akin to a literary magazine for children. Singer’s contribution to this publication was an English version of the first of the six Yiddish Chelm pieces published in Forverts the previous year, the last four of which formed the basis for The Fools of Chelm and Their History. These four pieces, free as they were of Jewish content, could be translated relatively easily for a general English-language young readership. “A shameless fish,” a traditional Chelm tale making fun of shtetl life, was another matter. Neither the rabbi nor the kheyrem nor the khutspe survive the transition from Singer’s Yiddish children’s story to its English reincarnation as “The Fools of Chelm and the Stupid Carp,” which follows the trend of many Singer translations, not burdening a general readership with unfamiliar, complicated, or conceivably alienating Jewish terms, concepts, and practices.154 Instead, these translations use the most familiar or easily grasped Jewish terms—food references, for example—for undemanding and unthreatening local color and invent new plot twists in which the deletion of too-Jewish material leaves gaps that need plugging.

Thus, in the English version of this story, meant for a general juvenile audience, the traditional seven days of deliberation are expanded to six months, during which the lucky carp is given fresh water and fed with “crumbs of bread, challah, and other tidbits a carp might like to eat” and is kept under close surveillance so that “no greedy Chelmite wife would use the imprisoned carp for gefilte fish.”155

The rabbi of the Yiddish story disappears entirely, and no one is released from anything as distasteful as a curse. Instead Gronam Ox is the lucky recipient of the largest carp in the lake at Chelm, “as a token of appreciation” for his “great wisdom.”156 When he bends down, he is slapped in the face, as in the Yiddish version, but now the fish is called not “cheeky” but “a fool, malicious to boot”; and a new concept is introduced for the young English-language readers: the wise Gronam Ox fears that if he eats the foolish carp, he will become foolish himself.157 The conflict is pared down to the binary opposition of wisdom and folly and to just two protagonists—the foolish sage and the wise fish.

The Yiddish children’s story, by contrast, features any number of sideshows and not just two protagonists, the rabbi and the carp, but also the human and piscine populations of Chelm. In this version, the wise men of Chelm prove their foolishness by accepting the fact that the carp is culpable, despite the rabbi’s exculpation of the fish on the grounds that it has had none of the advantages of a traditional Jewish upbringing, never studying Torah or hearing sermons in the synagogue. Still more whimsically, Groynem Oks, speaking for the prosecution, not only holds all the fish of Chelm fully responsible for their actions but also assumes that the fish of Chelm maintain community discipline just as their Jewish neighbors do.158

Inevitably, the sacrifice of the particularly Jewish elements for the sake of broad accessibility leaves the English version thinner and less inspired. Thus, in the English text, the verdict of the court regarding the carp is that, in the event of a repeat offense, it will be sentenced to life imprisonment in a specially constructed pool, which amounts only to a rehashing of the earlier joke about the carp’s comfortable detention while awaiting trial.

Shub’s attention to the seasonal demands of the American market is evident in her urging of Singer to produce children’s stories especially for Hanukkah. Accordingly, two of his three Chelm stories in Zlateh the Goat, “First Snow in Chelm” and “The First Shlemiel,” are given a Hanukkah setting, even though Chelm tales had previously made little or nothing of the Jewish holidays.159 Singer’s 1966 English-language children’s story “First Snow in Chelm,” no Yiddish version of which was ever published by Singer, is an adaptation of an especially well-known traditional Chelm tale. In earlier tellings, the synagogue official charged with summoning the men from their beds to early-morning prayers avoids trampling on Chelm’s immaculate first snowfall by being carried about on a table by four other individuals.

But, as with the tale of the carp eight years later, the story is made more universal. Singer reinvents the story in secular terms, free of minor synagogue officials and early-morning prayers. Now the wise men of Chelm, who could be the wise men of anywhere, misconstrue the snowfall as a shower of silver, diamonds, and pearls, a solution ex machina to their town’s fiscal crisis. A messenger must be sent around warning the Chelmites not to trample unawares on these precious objects, but he must do so without trampling on them himself; and so it is that the wise men hit on the clever idea of carrying the messenger about on a table.160

In spite of all this abridgment, bowdlerization, and loss of specificity, Singer’s English Chelm tales for children preserve something of the author’s skepticism toward utopian societies. As Chelm’s premier sage, Gronam Ox, declares in one of his speeches, “We do not wish to conquer the world, but our wisdom is spreading throughout it just the same. The future is bright. The chances are good that someday the whole world will be one great Chelm.”161

By producing Chelm tales in different languages and for different audiences, with different content and different objectives, Singer created new traditions of Jewish storytelling in the New World, with narratives that still bear traces of both the original Chelm tales and the sources of the original Chelm tales, which lie in the rich and influential foolish culture of early modern Europe.