2

How Foolish Is Jewish Culture?

Fools, Jews, and the Carnivalesque Culture of Early Modernity

Once upon a time, the impoverished residents of Chelm found themselves confronted with the desperate need to provide their shammes (beadle) with a new pair of trousers. Reluctantly, they concluded that the only fabric available to them was their megillah (Scroll of Esther), handwritten on parchment—treated animal hide. When Purim came around and the Chelmites needed to read the megillah in synagogue, their solution for the dilemma they had created for themselves was to drape the shammes over the bimah (lectern), reading the Esther story from successive sides of his new Lederhosen by rolling his torso over and over again, as they would a scroll.1

This story is first recorded in 1920 in Heinrich Loewe’s Schelme und Narren mit jüdischen Kappen (Rascals and fools in Jewish hats), and the phrase Khelmer naronim (fools of Chelm), which preceded the ironic formulation Khelmer khakhomim (wise men of Chelm), is significant for placing the Chelm tales explicitly within the genre of folly literature (Narrenliteratur in German). The Chelm tales might rank as the last bona fide creations within that major European literary tradition.

Typically, a key element of folly literature, and foolish culture generally, is the presence of what is often called the “carnivalesque,” a word coined by the Russian literary historian Mikhail Bakhtin (1895–1975). If Carnival refers specifically to the annual Christian festivities leading up to and including Mardi Gras, which is followed by the anticlimactic austerity of Lent, then the carnivalesque, in Bakhtin’s understanding of his term, includes the “total sum of all festivities, rituals, and forms of a carnival type.”2 The carnivalesque, like Carnival itself, “marks the suspension of all hierarchical rank, privileges, norms and prohibitions.”3 In the years since Bakhtin’s works were translated into English, French, and German in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the carnivalesque has become a widely acknowledged “epistemological category,” limited to no specific time or place and including a wide range of institutions, rituals, celebrations, performances, and texts.4

Carnival and the carnivalesque are historical phenomena that, as Aaron Gurjewitsch has shown, began with the urbanization of the Late Middle Ages.5 For Bakhtin, the primary function of carnival and the carnivalesque was to provide “temporary liberation from the prevailing truth and from the established order.”6 Nevertheless, subsequent thinking has seen some refinement of Bakhtin’s view, which accorded centrality to the release of tensions between high and low, official and unofficial. Carnival may have accomplished this by sanctioning a radical reversal of roles and power dynamics, but recent research suggests that more central to Carnival and the carnivalesque than the brief suspension of class distinctions was the mechanism it provided for communities to highlight perceived local problems, especially those involving sex, marriage, and gender roles.7

Either way, the embodiment of the carnivalesque is the fool, the symbol par excellence of transgressive behavior. The high-water mark of an extended period during which the word folly became synonymous with every kind of deviance was reached in the years spanning the publication of Sebastian Brant’s hugely influential Narrenschiff (Ship of Fools, 1494), Erasmus’s Praise of Folly (1515), and the anonymous Lalebuch (1597), which was retitled Schildbürgerbuch in the revised second edition (1598) and thereafter generally known as such.

Exhibitions of folly were especially prevalent in year-cycle and life-cycle events. Thus, in addition to the pre-Lenten Carnival (Fastnacht in German), with its carnival fools (Fastnachtsnarren), there was the post-Christmas Feast of Fools around the first of January and the similarly Saturnalian Feast of Asses later in the month.8 Folly frequently accompanied rites of passage, notably weddings, and the transition between adolescence and adulthood. Young European bachelors and even married men organized themselves into confraternities known as “fool societies.” In France, these groups had such names as Abbaye de Liesse (Abbey of Misrule), Abbaye de Conards (Abbey of Fools), and Abbaye de Cornards (Abbey of Cuckolds), with the leader of such groups titled, correspondingly, the Abbot of Misrule, the Abbot of Fools, or the Abbot of Cuckolds. These societies organized and participated in year-round carnivalesque performances—charivaris, masquerades, processions, and plays—that fulfilled a crucial role in the social and cultural life of the period, providing a structure for young men to rehearse masculinity.9

Carnival performances, court jesters, and other elements of foolish culture played a major role throughout late medieval and early modern Europe, but expressions of foolish culture exhibited considerable local variety. The heavy representation of folly in art and literature, propagated by the introduction during the fifteenth century of the woodcut and moveable type, helped spread consciousness of the varieties and possibilities of foolish culture, making its manifestations simultaneously more various and more universal.

Jewish Foolish Studies

The crucial place occupied by folly in early modern Christian settings has been studied extensively in recent scholarship. But foolish culture as a phenomenon in early modern Jewish culture seems hardly to have been considered. The scholarship that exists has been limited to two topics: the work of professional Jewish jesters and the festival of Purim or, more specifically, Purim plays.10

The pioneer in the field of Jewish foolish studies is Yitskhok Shiper (Ignacy Schiper, 1884–1943), who coincidentally represented Chelm in the Sejm (Polish parliament) from 1922 to 1927 and whose Geshikhte fun yidisher teater-kunst un drame fun di eltste tsaytn biz 1750 (History of Yiddish theater and drama from earliest times until 1750), published in Warsaw in 1923, devotes a chapter to the art of the Jewish fool of the sixteenth century.11 Tracing the fool’s evolution from the medieval lets, Shiper notes the changes that the figure undergoes in the sixteenth century. He does this based on inferences drawn from two manuscript collections of short texts, primarily songs. In one case, the copyist-collector is named Menakhem Oldendorf (the manuscript was completed in 1516 in Frankfurt am Main). The other manuscript was, in Shiper’s time, still attributed to Isaac Wallich (Ayzik Valikh) of Worms, who died in 1632, since he is the only named author of any of the compilation’s content.12

Shiper considers each compiler to have been a professional fool, following the occupation known interchangeably to early modern central European Jews as badkhn (jester) or marshalik (master of ceremonies), someone principally employed as a wedding entertainer. Shiper rightly recognizes that some of the texts in these two manuscripts pertain to foolish culture. However, there is no evidence to support his inference that they were professional fools. On the contrary, Oldendorf was employed as a preacher, ritual slaughterer, and copyist of manuscripts, while Wallich, son of a wealthy family, was a parnas (lay leader) of the important Jewish community of Worms.13

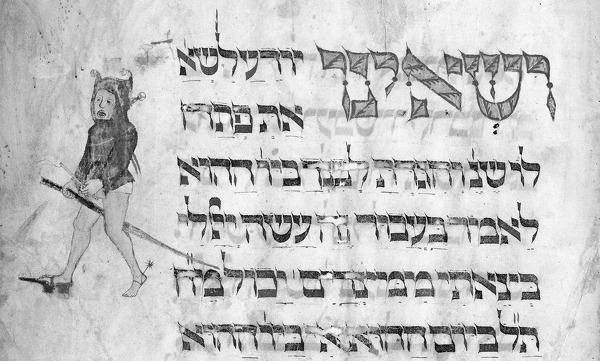

Maks Erik (Zalmen Merkin, 1898–1937) builds on Shiper’s ideas in “Di lirik fun di ‘narn’” (Lyrics of the fools), a section of his standard-setting work Di geshikhte fun der yidisher literatur fun di eltste tsaytn biz der haskole-tkufe (History of Yiddish literature from earliest times to the Haskalah period, 1928). Erik compares textual representations of fools in Christian and Jewish literature, concentrating on Jewish texts with Purim-related content, such as minhagim books (popular compendia of Jewish laws and customs) and Purim plays, and emphasizing the role of the latter in laying the foundations of Yiddish theater. Erik believes that the Purim play developed dependent on, or in close proximity to, the Christian carnival play. He also compares visual representations of fools in Christian and Jewish art and finds the costume of the Jewish fool identical with that of the “daytshn ‘nar,’” the (non-Jewish) German fool.14

More recent scholarly works on Jewish folly follow Erik and concentrate on literature connected to Purim. In an article titled “Le ‘Purim shpil’ et la tradition carnavalesque juive” (The Purim play and the Jewish carnivalesque tradition, 1992), Jean Baumgarten defines Purim, with its “liberating, recreational, and regenerative function,”15 as belonging to the “Jewish carnivalesque tradition.”16 Ahuva Belkin, in several articles, delves more deeply into the visual representation of Jewish fools in minhagim books and the Passover Haggadah, interpreting all these images as relating to Purim.17 Evi Butzer’s monograph Die Anfänge der jiddischen “purim shpiln” in ihrem literarischen und kulturgeschichtlichen Kontext (The origins of the Yiddish Purim plays in their literary and cultural-historical context) explores the many songs and plays in Hebrew and Yiddish that relate to Purim, on the basis of which she, too, makes connections to aspects of the German carnival plays.

Ever since Shiper began analyzing Jewish foolishness with his discussion of Jewish jesters as professionals, nearly all the work in this field has treated Jewish foolishness as something essentially Purim related, with scholars usually seeking parallels with the pre-Lenten Carnival. While this is a valid and valuable subject of research, it is not the whole story.

Although some scholars continue to regard carnival as exclusively bound to Christianity, the resemblance between Purim and Carnival was noted as far back as the early modern period, when the “polemical ethnographies” of Christian Hebraists and Jewish converts to Christianity routinely described Purim as the Jewish Fastnacht (Carnival).18 The proximity in the calendar of the two holidays was bound to lead to this connection.19 The nineteenth century saw a debate on Purim, Carnival, and their relative alleged excesses. The late-nineteenth-century scholar Moritz Güdemann tries to compare evidence of the extensive drunkenness during Carnival and Purim, seeking, as Elliott Horowitz puts it, “to demonstrate that Jews, unlike their Christian neighbors, had not exceeded the bounds of good taste in their pursuit of Purim amusements.”20

The Israeli historian of Yiddish literature Khone Shmeruk (1921–1997), in a chapter on comic characters in early Yiddish theater in his 1988 book Prokim fun der yidisher literatur-geshikhte (English added title: Yiddish Literature: Aspects of Its History), takes a different approach. He proposes that Yiddish drama could only develop once European drama became less Christian, that is, less theological or less entangled with the church. One argument he makes seems particularly persuasive. Shmeruk identifies the secular stock characters that developed throughout Europe in the seventeenth century as a major influence on the Yiddish Purim-play repertoire. In particular, he finds Mordecai’s persona in the Purim plays strongly influenced by the buffoonish Hanswurst (Hans Sausage) and Pickelhering (Pickled Herring), German theatrical counterparts of Mr. Punch.21

Notwithstanding the value of many of these studies, what is still lacking is any sense of a far more pervasive Jewish foolish culture, one not confined to Purim. In the perennial debate on the nature of the relationship between Jewish and non-Jewish cultures, nearly all commentators see Christian or Western foolish culture as the source of Jewish foolish culture.22 Thus, Franz Rosenberg views the humor of the Purim play as “ein durchaus getreues Gegenbild” (a more or less exact match) for the German Carnival play.23 Similarly, Erik concluded that the relationship between the Jewish fool and the non-Jewish fool was one of nokhamung (imitation).24 Jean Baumgarten, too, noting the resemblance of the Purim plays to the Christian Fastnachtspiele (Carnival plays), with the fool playing a major part in both repertoires, states that the Christian drama provides the “antecedents” of the Jewish drama. Similarly, Belkin highlights the “affinity” of Purim rituals to the pre-Lenten Christian Carnival.25

Historians of Jewish culture have often aspired to locate the relationship between Jewish and Christian practices in any given situation on a continuum between embeddedness and autonomy. Compellingly, Moshe Rosman avoids the independent/dependent dichotomy and suggests that similar practices in coexisting cultures respond to a shared human need and are “cultural parallels [that] should not be seen through the prism of influence, but rather that of comparison, as two variations of a common tradition whose roots are obscure.”26

Foolish culture, therefore, can be thought of as a set of common cultural materials structured through a “symbolic grammar.”27 These cultural materials consist of material goods, such as literary and visual representations of fools and other artifacts, and folly-related symbolic material, that is, concepts and language. The symbolic grammar of foolish culture describes the logic and rules in accordance with which rituals are performed and ideas are conceived. Thus, when a Yiddish Seyfer minhogim (Book of customs), printed in Venice in 1593, is illustrated with a famous woodcut of three men in a Purim procession, the image reflects a broader foolish culture. Arranged as a procession, a common element of foolish performance, the men wear outfits that feature such familiar foolish symbols such as motley, the fool’s cap, bells, and donkey ears, and one carries an oversized tankard.

Recognizing the concept of “foolish culture” makes it possible to examine how Jewish foolish cultures related to neighboring Christian foolish cultures. As noted, scholarship on the subject agrees that the figure of the European Jewish fool had a strong connection with the foolish figures of Christian culture. If one assumes that all ideas, institutions, symbols, and practices relating to foolishness and the carnivalesque constitute “foolish culture,” then Jewish foolish culture can draw from this reservoir of ideas and practices just as Christian foolish culture does. On the other hand, differences between these traditions can be observed. The occasion for the procession in the Seyfer minhogim is the Jewish holiday of Purim, and it is not surprising that two of the fools have beards to indicate their Jewishness. By contrast, none of the great number of fools in the foolish processions in the woodcuts that accompany Sebastian Brant’s Ship of Fools is bearded, since fools are by convention depicted as clean shaven in Christian art.28

Purim fools, from Isaac Tyrnau, Minhogim, trans. Simon Levi Ginzburg (Prague: Ortits, 1610–1611), fol. 91v (from Johann Christoph Wagenseil’s library), Universitätsbibliothek Erlangen-Nürnberg H61/WAGENSEIL.VK197

To appreciate the scope of early modern Jewish foolish culture, the cultural milieu that is the point of departure on the route to Chelm, it is essential to grasp the connections between Jewish and Christian expressions of foolish culture. As we shall see, there was in this period, parallel to Christian foolish culture, a rich Jewish foolish culture that generated a wide array of festive events, rituals, and texts.

Folly in Jewish Graphic Materials: The Passover Haggadah

The most illustration prone of late medieval and early modern Hebrew manuscripts and printed books is the Passover Haggadah, and most of the important illuminated manuscripts fall into one of two groups: those produced mainly in the fourteenth century in Spain, especially in Catalonia, and those produced, especially during the middle to late fifteenth century, in Germany and in northern Italy, with its influential German Jewish immigrant communities.

The son who does not know how to ask, from the Rothschild Haggadah (1450), National Library of Israel, Ms. Heb 4º 6130

The most prominent of the artists responsible for these manuscripts was Joel ben Simeon, also known as Feibush Ashkenazi, who worked in Cologne and Cremona. Numerous surviving illuminated Haggadah manuscripts, whether executed by him or attributed to his workshop or to other illustrators of Ashkenazic manuscripts, include a miniature painting of a fool.29 He is readily identifiable from the motley in which he is dressed, the foolish symbols such as the hobbyhorse given him as accessories, or his dishevelment, another unmistakable symbol of foolishness.

The placement of these images is not arbitrary, and their function is not merely decorative. Instead, the fool is depicted at the same point in each of these works. He appears alongside the passage in which the Torah is homiletically interpreted as dividing people into four types (the “four sons”). To each son, the story of Passover is to be explained according to that type’s defining personality or ability. The character of each of the first two hypothetical sons—the wise son and the wicked son—proves relatively unambiguous compared to that of the other two: the “simple” son and the son “who does not know how to ask.”30

In several of the early modern Ashkenazic manuscripts, such as the Parma Ashkenazi Haggadah (Ms. Parm. 2895) and the Rylands Ashkenazi Haggadah, the third son is illustrated as a fool. But more frequently, as in the cases of the Washington Haggadah, the Second Nuremberg Haggadah, the First Cincinnati Haggadah, the Rothschild Haggadah, the Haggadah included in the Rothschild Miscellany, and the Paris Siddur with Haggadah, it is the fourth son who wears the uniform of a fool.31

Characterized as unable to ask the reason for the unusual rituals of Passover night, the fourth son automatically connotes for modern readers the image of a preschool child. But for these illuminators and their audience, an inability to formulate a question suggests not infancy but “natural folly,” or what modernity regards as mental disability.32

This interpretation of the fourth son is not limited to illuminated manuscripts or to the fifteenth century. The Mantua Haggadah of 1560, celebrated for its woodcuts, also represents the fourth son this way, modeling its depiction on the image of a natural fool executed by Hans Holbein the Younger to accompany Psalm 53 (“The fool has said in his heart, ‘There is no God’”), from his set of illustrations commissioned for the Protestant Zurich Bible.33

Folly in Yiddish Literature: The Case of Till Eulenspiegel

Among the works much appreciated by early modern Jews, as well as by early modern Christians, were the stories about Till Eulenspiegel, the great fictional foolish figure who made his first appearance in a Schwankroman (jest novel) printed in Strasbourg in 1510–1511.34 The book describes his deeds in what were initially ninety-six tales arranged in loosely biographical order. The protagonist transgresses all norms of society, be it at court, in the city, or in church, vis-à-vis women and men, adults and children, Christians and Jews. Typically, Eulenspiegel manages to get away with violating the rules by interpreting expressions and metaphors in a strictly literal sense. His actions, which generally end in uproar, serve to scrutinize social conventions and mores.35 Through the book’s many editions and reworkings, it has remained a universally familiar presence in German literature, despite its bowdlerization in the nineteenth century, when, repurposed for children, it was adapted into a didactic text, entirely inoffensive and thus self-defeating.36

Eulenspiegel was translated into Yiddish at least four times, always on the basis of a contemporary German edition rather than an earlier Yiddish edition. All the Yiddish versions leave intact Eulenspiegel’s persona as a trickster fool, and whatever additions and alterations are made in the Yiddish versions, the stories generally follow the German plotlines.

The earliest Eulenspiegel, transcribed into Hebrew script from a sixteenth-century German edition, includes 102 tales and was compiled around 1600 by the scribe Benjamin ben Joseph Merks of Tannhausen. It is part of a Yiddish manuscript held in the Bavarian State Library.37 The text is only slightly modified from known German precursors, to the extent of omitting or rephrasing occasional patches likely to prove jarring to Jewish readers. But the book is not Judaized in any more active sense than that, and certainly the hero, or antihero, is not presented as a Jew. On the contrary, the Merks manuscript retains a reference to Eulenspiegel’s shmad, the Yiddish pejorative for baptism, whether of Jews or Gentiles.38

To judge from Johann Christoph Wolf’s Bibliotheca Hebraea, there appear to have been two editions of Eulenspiegel in Yiddish printed at the beginning of the eighteenth century, but if so, both are now lost.39 Nevertheless, when Lutheran Pietist missionaries to the Jews from Johann Heinrich Callenberg’s Institutum Judaicum et Muhammedicum in Halle went into the field, they often visited Jewish bookstores or talked to Jewish booksellers. In printed accounts of these travels, edited and probably embellished by Callenberg, one missionary is reported in 1731 as having seen “Eulenspiegel, Clausnarren, both in Yiddish, and other similar things.”40 The report, which expresses a dislike for this kind of literature, says that the missionary asked the bookseller what use Jews could have for such books, to which the bookseller apparently replied that their purpose was to keep people amused on the Sabbath.41

Callenberg’s narrative continues with the missionary expressing incredulity that Jews had time to waste on their holy day. Was not the Sabbath created for the study of the law, which humdrum obligations made it hard to pursue on weekdays? The bookseller observes that men did indeed spend the Sabbath studying the Law and that the books about which he had inquired were for women only. The missionary then remarks that this was the trouble with the Jews: women did not study the Bible and so could not cultivate their soul.

The first surviving Yiddish Eulenspiegel in print was published in Prague in 1735. Remarkably, it includes five additional stories unknown in the German tradition, which give the protagonist the face of a monkey, attributed to telegenesis, the ancient belief that whatever a woman was looking at or thinking about when (or after) she conceived was liable to influence the appearance of the child.42 The idea was likely familiar to the Yiddish translator from its preservation in the Talmud. Thus, “Aylen-Shpigel had a face like a monkey,” the symbolic epitome of folly, “because his mother had looked at a monkey during her pregnancy.”43

This edition incorporates additional stories, in which Eulenspiegel travels to distant lands, and following the ancient tradition of imagining bizarre-looking humans at the ends of the earth, encounters such fantastic types as enormously strong women, people with canine features, and others with monkey features like himself.44 But unlike any known German version of Eulenspiegel, this Yiddish edition contrasts the fool’s otherness with the strangeness of other “others,” and he finds himself afraid of the strong women, almost eaten by the “dogs,” outwitted by the “monkeys,” and much relieved to be back on a ship heading to a “German land.”45

The third Yiddish edition of Eulenspiegel, evidently based on a lost German version, appeared in 1736 in Homburg vor der Höhe, outside Frankfurt am Main. Except for one story featured in the German original that makes fun of a Jew, all the other Eulenspiegel stories are present here: it is only gratuitously Christian details that are replaced.46 For example, an incidental reference to a Marien spiel (a play about the Virgin Mary) is neutralized into a naren shpil (a foolish play).47 The much-abridged fourth Yiddish Eulenspiegel with only thirty-three stories, once again apparently based on an unknown contemporary German version, was printed in Nowy Dwór in 1805–1806.48

These late editions, as well as the many German editions available throughout the nineteenth century, made a great impact on the literary formation of the character known as Hershele Ostropoler, the most prominent individual fool in Jewish folklore. Tales about Hershele, said by one author to have been known as “the Jewish Till Eulenspiegel,” are clearly rooted in the Yiddish and German versions of Eulenspiegel, in Jewish foolish culture more generally, and in eastern European Jewish oral traditions.49 The Hershele tales’ multiplicity of origins bears some resemblance to the much more complex background of the Chelm tales.50 Hershele made his way into modern Yiddish fiction, notably in Y. Y. Trunk’s book Der freylekhster yid in der velt oder Hersheles lern-yorn (The happiest Jew in the world, or, Hershele’s apprentice years) and also appeared in a number of English stories aimed at children.51

Folly in Jewish Practice: Customs, Ceremonies, and Songs

Foolish culture made its way into early modern Hebrew and Yiddish books of customs and even, pictorially at least, formal codes of law. An Italian manuscript of Sefer ha-zemanim (Book of seasons), the section on the events of the annual cycle in Maimonides’s codification of Jewish law, Mishneh Torah, opens with an illustration of a Purim celebration that prominently features a Jewish fool dressed in motley.52 The Yiddish Seyfer minhogim features Jewish fools in a Purim procession, also dressed in motley and carrying horns, trumpets, and other musical instruments. But some of these works contain textual as well as visual evidence of Jewish foolish culture.

Of special interest is the book of local customs written by Yuspa Shammes, the seventeenth-century beadle and scribe of the Jewish community of Worms. This work includes a vivid description of the celebration of “Shabbat ha-Baḥurim,” the Young Men’s Sabbath that was an annual feature of the Worms Jewish calendar.53 On the Sabbath following Purim, older boys and younger unmarried men would gather at a house relatively far from the synagogue. The group would leave the house in procession, dressed in their Sabbath mantle and mitron, a miter or pointed hood, and walk in pairs toward the synagogue with their chosen leader, the so-called knel gabbai, dancing in front of them and acting the fool.

On reaching the synagogue, many actions that were inconceivable under normal circumstances but typically carnivalesque would ensue. The young men could sit in the women’s section or occupy the seats assigned to the community elders, and they would monopolize the honorific duties associated with the reading of the Torah, duties normally reserved for substantial householders. On subsequent evenings, these householders would open their homes to the young men, hosting parties that would continue until the young men finished however much wine these prominent figures, depending on their wealth, were required by the community to provide.

All this is reminiscent of the carnivalesque traditions of the Christians of Worms on the Feast of St. Nicholas at the beginning of Advent. These similarities are especially evident in such elements such as fancy dress, masks, the crossing of normally strict boundaries, and the inversion of usually rigid hierarchies.

By analogy with the abbots and priors and other mock-ecclesiastically titled officeholders in the Gentile fool societies, the “knel gabbai” to whom Yuspa refers is clearly a mock-synagogal title corresponding to something like an “abbot of misrule.”54 The gabbai (Hebrew for “collector”) is, historically, the lay official of a Jewish community in charge of a particular aspect of communal life, especially poor relief, including the collecting and distributing of taxes, fees, and donations. Knel is more problematic. The only known word to which it seems at all likely to relate is the German verb knellen, “to bang” (knallen in modern German). The Yiddish verb knelen means “to teach somebody,” in the sense of beating knowledge into him, with a stick if necessary, a vivid reflection of the pedagogic methods of the medieval and early modern kheyder or Jewish elementary school.55 In Yuspa’s work, however, the reference is likely to a specifically carnivalesque title, in all probability alluding to the carnivalesque emphasis on cacophony or disorder.56

There are remarkable parallels between Yuspa Shammes’s description of such customs in Worms and the Oxford Old Yiddish Manuscript Songbook, the so-called Wallich manuscript, compiled over an extended period in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, which contains more than sixty songs and plays.57 The manuscript includes several texts steeped in the foolish culture of the early modern period, including the song “Pumay, ir libn gezelen” (Pumay, you dear companions), which reflects both the carnivalesque customs of “Shabbat ha-Baḥurim” and more widely observed carnivalesque Purim traditions.58

“Pumay, ir libn gezelen” is told from the perspective of a singer garlanded with bells as foolish symbols, who arrives at a party organized by a fool society. The singer is identified as a member of “the king’s young men.”59 Later in the song, the “king,” with a pillow to make his belly look larger, is depicted as joining the company in their rejoicing.

The Purim king, or Purim rabbi, is a carnivalesque figure with a long tradition of close association with drunkenness. Reference to such a figure is first found in parodies originating in medieval Provence, notably Megillat setarim (Scroll of hidden things) and Sefer ha-bakbuk (Book of the bottle), both attributed to Gersonides (1288–1344) and both circulating widely across Europe.60

The Purim king of Worms, then, derives from both a shared foolish culture in the Rhine valley and a long-standing Jewish literary tradition with roots in the Rhone valley.61 The young men in the song that the Oxford Old Yiddish Manuscript Songbook preserves show support for their Purim king by joining with him in some drinking and then studying Torah. The riotous nonsense of the text evokes the young men moving from house to house for the festivities described in Yuspa Shammes’s book.

The Oxford Old Yiddish Manuscript Songbook contains another song, unconnected to Purim, which makes sense only in relation to practices prevalent among young men’s fool societies of the time. In this song, sixteen Jewish men are apparently named and shamed for having illicit sexual intercourse with Jewish and Christian girls and women.

The song was first noted as exemplifying Jewish foolish culture in early modern Yiddish literature by Yitskhok Shiper in his history of Yiddish theater and drama.62 Shiper’s assumption that the protagonists are “khsidim fun umreyner libe” (devotees of impure love, libertines) is based on Felix Rosenberg’s study of the Oxford Old Yiddish Manuscript Songbook, published in the Zeitschrift für die Geschichte der Juden in 1888 and 1889.63 Rosenberg describes the sixteen as men who pay homage to “Venus vulgivaga,” that is, Venus in the character of goddess of promiscuity.64

For these scholars, the song falls clearly into the category of Jewish folly literature because of its nibl-pe (profanities) and permissiveness. Shiper considered the “Ayzik Kitel” named in the song to be its author, and he celebrates him as one of the great Jewish fools of the sixteenth century. In contrast, other scholars question whether the song qualifies as folly literature at all, given its distasteful subject matter.65

There is no doubt, however, that the song is rooted in the carnivalesque culture of Early Modernity. In its twenty-seven quatrains, it alludes in various ways to the foolish performances and foolish language of the time. The question remains, however, as to what exactly is foolish about this Yiddish song, which in each stanza relates, in graphic detail and with elaborate period metaphors, what amounts to the same story over and over: how each of the sixteen men had sex with shikses (Gentile girls), goyes (Gentile women), or prostitutes or how they impregnated their cook or maidservant or, in one instance, the Shabbes goye, the woman who helped with domestic tasks on the Sabbath so that the Jewish members of the household might avoid profaning their holy day.66

The foolish institution evoked in this song is the charivari, a ritual designed to expose local misconduct, particularly by writing derisive lyrics to song tunes that humiliatingly were performed in public, accompanied by raucous and discordant music.67 The charivari was a rite staged by members of the fool societies.68 The purpose of these performances was to deal vigilante style with breaches of a community’s sexual and marital norms.

The pedagogical function of this institution as a primitive kind of adolescent or premarital sex education seems clear enough.69 But it was not just the perpetrators of these offenses whom the charivari casts as fools. In the institution of charivari, as in this period generally, folly is seen as ubiquitous. Cuckolds, along with other seemingly innocent individuals, such as henpecked husbands and old men with young brides, are just as likely to be mocked as philanderers and seducers. Young performers even presented themselves as fools, proudly choosing foolish names for their group and its members and wearing such foolish symbols as horns.

The song in the Oxford Old Yiddish Manuscript Songbook reflects the ritual of the charivari in the way that it features those two groups, the ridiculed and the ridiculers. The last line of the song refers to these sixteen men as being the type who “also like to ride on such pushcarts,”70 a remark that may suggest the ceremony of carrying the cuckold, often with horns on his head, around town in a cart.71 Rather than literally executing this sentence, the narrator of the song gives these wrongdoers an equivalent punishment, listing them and their misdeeds in detail and thereby exhibiting them on a literary pushcart.

Yet the song is peculiar enough to raise the possibility that the real target of this charivari is not what it appears to be. Four of the sixteen named individuals have been traced in archival sources, and all turn out to have been at the center of a cause célèbre in the Jewish or civil courts during the late sixteenth century.72 Two of these cases are of a nonsexual nature, involving a contested inheritance and a civil suit with a Gentile. Conceivably, the song’s true purpose was to group together and to highlight a succession of problematic cases involving prominent members of various Jewish communities in southern Germany and Switzerland, referring to these sensitive matters obliquely through the sexualized language characteristic of charivari.

Archival sources also preserve records of named individual fools, that is, badkhonim, professional entertainers at Jewish weddings and other community events, such as the eighteenth-century Löb of Fürth.73 There is also a suggestive reference to Volf Nestler as the official fool of the Jewish community of Prague, who is recorded as leading a procession of Prague’s Jews to celebrate the birth of the Habsburg Prince Leopold in 1716, in a description that shows him not just acting the fool but also making use of gender-crossing foolish costume: “After this Volf Nestler, the community fool [kahals nar], came riding along, wearing gold sequins and a red veil of the kind favored by the women of Prague. In addition, he had on a blue coat, buttoned from the neck down and spreading out over the entire horse. The whole outfit was adorned with little horn-shaped pastries, which he would blow as if they were post-horns and consume.”74 The description, published in Yiddish with an annotated German translation, survives thanks to Johann Jacob Schudt (1664–1722), who reserves any displeasure on this occasion for the Yiddish author’s choice of the word herndlikh for “little horns,” whereas, in his opinion, the correct diminutive should be Hörnlein.75 As for Wolf Nestler’s performance, that passes virtually unremarked. All Schudt does in his annotation is state the obvious: that the fool blew the pastry horns before eating them to make the audience laugh. Nothing about the fool’s behavior or appearance or even his existence seems to have occasioned surprise, let alone disapproval. Rather, Nestler’s use of foolish symbols belonged within a shared foolish culture, and the meaning of those symbols must have been clear to Jews and Christians alike.

Fools, foolish rituals, foolish symbols, and a complex concept of folly were clearly a palpable and continuing presence in the life of early modern European Jews, within Jewish communities as well as all around them. Shared symbols and ideas of folly made a book such as Eulenspiegel entirely intelligible and highly appealing to Jewish readers. Another such case, as we shall see, is that of the Schildbürgerbuch, a work that focuses not on an individual but on exploring how an entire community succumbed to folly. The Schildbürgerbuch was one of the more influential books in central Europe throughout the seventeenth century, and it continued to exert an influence in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and even the twentieth century.