The first incident I would like to talk about happened on March 13, 2006, involving a detainee at Abu Ghraib’s in-processing center.

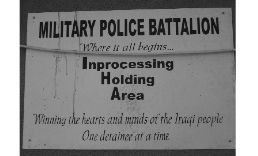

That was the sign outside the in-processing center. “Winning the hearts and minds of the Iraqi people, one detainee at a time.” I can tell you how we won one of those minds. My fellow medic and I were making our rounds through the in-processing center when a truckload of new captures came in. They often came in truckloads because we would arrest any military-aged male in the vicinity of an incident.

As we were going through these people, evaluating them and checking them out, one young man stood out to me as being particularly irate and kind of out of it, seemingly drunk. I felt it was necessary to take his blood sugar. Normal blood sugar is between 80 and 120 mg/dl. When I took his blood sugar, it was 431 mg/dl. The detainee could speak English very well and said he had been taking insulin and that he had been captured by the Iraqi forces, held for approximately four to five days, and during that time they had not given him his insulin. Supposedly it was in his personal effects.

I called the officer in charge of the Abu Ghraib hospital and requested that we transport this detainee. I was told twice over the phone, ordered by the captain of the 344th Combat Support Hospital, that I could not transport the detainee, and that he needed to drink water. She also stated that he was a “haji, and he probably wouldn’t die, but it would not matter if he died, anyway.”

In the early hours of March 14 my partner and I went back to the camp to see the same individual who was now more irate, more intoxicated looking, and sweating profusely. I called my captain again, and again was denied permission to take him to the hospital. There was little I could do, and she told us to give him water and a 14-gauge IV. A normal IV is an 18- to 20-gauge. So we did that, and then we got off our shift.

On the morning of March 15, the MPs mistook this twenty-three-year-old young man’s diabetic shock for insubordination. They pepper-sprayed him and put him into a segregation cell in the sun, where he spent his last few hours. He died en route to the hospital in one of our ambulances. Captain Hogan said that we had never called her and that we had never tried to transport the detainee.

The next day, my partner and I were awoken out of our beds and told that we needed to go down and be interrogated by a CID colonel about the death of the detainee we had seen the previous night. Maybe three days after that, we were interrogated again by a lieutenant colonel, at which time I filled out a five-page sworn statement. We were cleared of everything, and Captain Hogan remained the night shift officer in charge of the hospital at Abu Ghraib.

I also have a second story that emphasizes racism and how the word “haji” is often used, similar to how a racist in this country would use the “N-word.” You see, we used different ambulances for the detainees than we did for medical support on American convoys. They had older equipment. Often the fluids or the prescription drugs would be expired, sometimes by years.

I got a call saying there was an unconscious detainee in one of the camps that usually held very docile prisoners. My partner drove while I prepared the oxygen and I attempted to prepare the Automated External Defibrillator (AED). However, my platoon sergeant ordered the wrong pads for the AED, so when I arrived on the scene I was unable to shock and revive him, which we learned later would probably have saved his life. We attempted to ventilate him on the way to the hospital but we could not. The mask was so deformed due to the heat and because it was so old. I ended up performing mouth-to-mouth resuscitation on the detainee.

A lot of people called them hajis. To me, this detainee was just an old man that could’ve been somebody’s father, grandfather, or uncle. I remember exactly how he looked, and I remember exactly how he felt, dying in my hands. I revived him for about fifteen seconds at which point my assistant called ahead to the hospital but they didn’t respond.

We got to the hospital to find them very apathetic. The two medics working the emergency room were sitting on cots, sleeping. The emergency room doctor was playing Slingo, the computer game. In the emergency room I had to continue performing mouth-to-mouth resuscitation on this detainee. I later overheard many comments about how “That medic made out with a haji.” I was isolated by that incident. A lot of people came up to me and said, “How the hell could you do that?” I told them, “What if that was your grandfather or your father? Wouldn’t you do the same thing?”

I could see why people wouldn’t want to take care of Iraqis because, at the same time, we treated wounded U.S. soldiers. I remember a time when I treated a marine with his legs blown off who died in our care. About a half an hour later, I had to give a detainee pills for a headache. But as a medic, and as a professional, I needed to treat these people the same. They are human beings, and I couldn’t treat them like subhumans.

I’ll just finish up with a very short story. Me and the same medic from the first incident were called to the in-processing center where they had a semiconscious man in the back of a five-ton truck. He was restrained with his hands cuffed behind his back and his feet cuffed. He was also blindfolded. The sergeant in charge asked me if I felt the detainee could walk the approximate fifteen feet to the doorway. I revived him and said, “He could probably walk with assistance to the doorway.” The sergeant picked up the blindfolded man by the flexi-cuffs, threw him off the back of the Humvee, face-down, chest-down, in the gravel, and said, “You can’t spell abuse without Abu.”