38

“Nikki, this is Preston Randolph.” Apparently the man made his own calls on Saturdays. “I talked to a few executives at the network who put me in touch with the producer of Faith on Trial. I had concerns before, but I’ve got serious issues now.”

“What happened?”

“I told this guy Murphy that I didn’t like the way they were portraying my client. Even the show’s director thinks that Dr. Kline’s got serious potential for television, but they’re killing her with this May-December romance thing.”

Nikki stiffened. She had an urge to defend her judge—it wasn’t like he was a total loser for Kline to be hanging out with. But Nikki also had plans. It would be hard to use Preston if she didn’t keep it civil.

“Plus, the way they set my client up for that ethical temptation at work, even before she got to the island—it was totally underhanded. She passed their little test, but still . . . I told him I wouldn’t hesitate to file a lawsuit even while the show was running in order to get Dr. Kline’s story out there. That’s when he dropped the bombshell.”

Preston waited, apparently to let Nikki prompt the next response. Trial lawyers like Preston did that instinctively—everything is drama. “What bombshell?”

“He said he had some confessions on camera from Dr. Kline that could be career threatening if they came out. I challenged him, and he gave me the specifics. He mentioned that he had the same types of career-ending stuff on other contestants. You know anything like that with regard to Judge Finney?”

Twenty-four hours ago the answer would have been no. But Nikki had asked around at the courthouse yesterday after getting Finney’s message about the speedy-trial cases. She had read the old newspaper articles that blamed it on the prosecutors, but she also had a confidential talk with the clerk who worked for Finney at the time.

“Judge Finney?” Nikki asked, as if it were the most preposterous question she had ever heard. “It’s hard to imagine anybody having dirt on him.”

“Yeah. Well, I thought the same thing about Dr. Kline.”

There was silence for a moment as Preston apparently tried to figure out the next step. “Did you say you’d be in Washington next week?”

Nikki had almost forgotten. “Uh . . . yes. Monday.”

“Can you stop by the office? I’ve talked to a few family members of the other contestants—Hadji’s parents and Hasaan’s wife. We might be able to hook them up by videoconference and get a plan together.”

They settled on a time, and Nikki saw her opening. “Have you got any private investigators working for you?” She already knew the answer.

“Sure.”

“Do you think they could do background checks on Cameron Murphy, Bryce McCormack, and Howard Javitts by Monday?”

“I think so. Maybe we can get some dirt on them to use as bargaining chips—is that what you’re thinking?”

“More or less. And I’ve got a few names for your investigators to keep an eye on—see if there’s any connection between these guys and the men they’re investigating or their families.” Nikki spelled out a list of defendants who had been freed in the speedy-trial cases, including Antonio Demarco. “I’ll tell you on Monday why I’m asking about these men.”

“Okay,” Preston said.

Nikki tried to keep the conversation going for the next minute or so—“Got any big plans for the weekend?”—but it became obvious that Preston was ready to get off the phone. She let him go without much of a fight and with no resentment. The Moreno charm always worked best in person. That way, the legs could do part of the talking.

Kicking back in a comfortable pedestal chair in her television room, Nikki continued her Internet research on Javitts, McCormack, and Murphy. The men were hard on wives. Combined, they had gone through seven, and Javitts was the only one still married. Nikki was putting together family trees, complete with alimony and support obligations, as well as criminal records for the men. To do this right, she would have to interview all the living ex-wives—always a ready source of dirt. Complicating matters was a name change by Murphy, formerly a small-time actor named Jason Martin. She hadn’t yet pulled up any dirt on Murphy under his prior name, but you don’t go through a name change for no reason.

But now that Nikki had scammed some help from Randolph’s top-notch investigators, she found it hard to garner much enthusiasm for her own research. The pros would have a report prepared for her on Monday. She would use their work as a springboard for any further investigation. Obviously Finney thought one of these men was out to get him because of something associated with the speedy-trial cases. But Nikki had found no obvious links, and she had been working on it for hours.

She needed a break. She took another glance at the small book that had arrived that morning. Her brand-new copy of Finney’s Cross Examination. She didn’t doubt that another message would be arriving from Finney soon and that Nikki would have to know the cipher system used in chapter 2 of the book to understand it. Sure, Wellington would be able to solve it. He probably already had. But still, if Nikki could solve it as well, then she would be firmly back in the driver’s seat. She wouldn’t even have to tell Wellington about the message.

She glanced at her watch. Not quite noon. She would take no more than two hours to work on the cipher before she got back to her research. Time might be of the essence for Finney, but everyone needed a break.

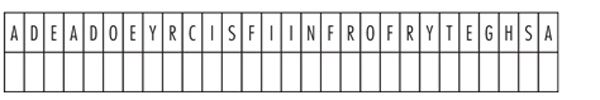

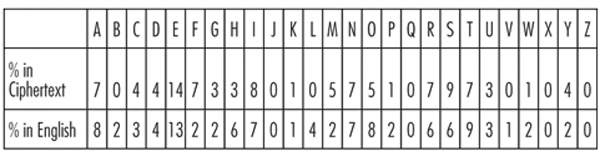

She started by making a chart of the code letters contained at the beginning of chapter 2, just as she had seen Wellington do. She would need to find a pencil with a good-size eraser for her guesses at what the code letters stood for.

The next step would be tedious, but there was no way around it. She would have to count up the total number of times each letter was used in the code message and compare the result to the average frequencies of letters in the English language. Cruising around the Internet for a chart showing letter frequencies, she struck gold.

Nikki landed on a site that hailed itself as the Black Chamber and included a substitution cipher–cracking tool that was, in her opinion, about the coolest site ever invented by humankind. It looked to Nikki like it had computerized the work of cracking codes. She wondered why Wellington hadn’t already seen this site . . . or maybe he had. She remembered how he stepped outside the noisy sports bar to call his mom that first night, allegedly to get information about letter frequencies. Either way, she couldn’t wait to see the look on Wellington’s face when he found out she had cracked this cipher all by herself. Well, sort of.

For starters, all she had to do was plug her ciphertext into a blank box on the site. She carefully transcribed every letter. Now there were several buttons that would kick out an analysis of the ciphertext. The button that looked like it had the most promise was Show Solution. She almost cheered as she clicked it. But her spirits soon plummeted when the solution came back “undefined.” Did that mean she had to be smarter than the computer to solve this code?

Not yet. There were still a few more tricks the Black Chamber had up its sleeve.

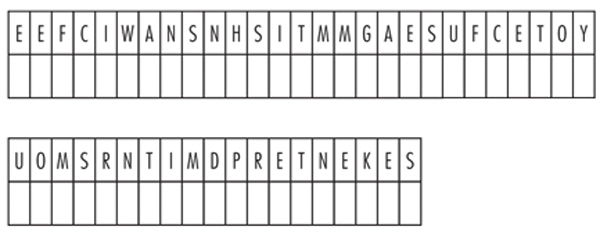

The next button she clicked was called Frequency of Individual Letters. It automatically, in less than a second, produced the following chart—a thing of absolute beauty in Nikki’s opinion, saving her a half hour of counting.

Nikki jotted a few notes. She assumed that either the letter E or the letter S in the ciphertext, the two most popular letters, represented the letter E in the English language. The other probably represented the letter T. And since it didn’t make sense for a letter in the ciphertext to be the same letter in the regular text, she assumed that E in the ciphertext stood for T and that S in the ciphertext stood for E.

But she wasn’t done with her shortcuts yet. The Internet site had another useful tool. This one was called Vowel Trowel. The description explained, just as Wellington had a few days ago, that vowels were more “sociable” than consonants and tended to border lots of different letters. Consonants, the site said, were “snobs,” bordering only certain other letters. I’m liking consonants better all the time, Nikki thought. When she clicked on the button, it showed her how many different letters each letter in the ciphertext was adjacent to. From this, she learned that both E and S were probably vowels.

If they were both vowels, then the ciphertext E probably stood for A and the ciphertext S probably stood for E. She started filling out her graph. She placed E in for the plaintext everywhere the ciphertext showed S. Then she put an A for the plaintext where the ciphertext showed E.

The next button she clicked was something called Common Digraphs. It showed how often certain pairs of letters were together in the ciphertext and the most common letters found together in pairs in the English language. Things were starting to get confusing. Another tool, called Frequency of Pairs of Letters, didn’t help much either. She tried looking for a repeating pattern of three letters together, like Wellington had done, but this was a dead end too.

Nikki looked at her data, substituted some letters in her chart, then frowned at the nonsensical message being generated. It all seemed so logical and easy when Wellington explained it. But after nearly two hours, all Nikki had was a lot of scribbling and erasure marks on her chart.

She set down her pencil. The eraser was black around the edges and well-worn. Who cared? She could probably solve it if she really wanted to. But why waste more time? The important thing was investigating the backgrounds of Javitts, McCormack, and Murphy. She would leave the menial task of deciphering to a specialist like Wellington Farnsworth.

Maybe he was smarter than the computer.