39

Finney was no scientist. Math he loved. The law he had mastered. But science? People who understand science go to med school, not law school. The only thing lawyers needed to know about science was that doctors carry big insurance policies. And if something goes wrong, then somebody must have been negligent.

But tomorrow Finney would be expected to cross-examine some scientific expert in front of a national television audience, exposing Finney’s scientific ignorance for all the world to see. He didn’t even know what kind of scientist might take the stand.

He assumed it would have something to do with the showdown between science and religion on matters of origin. The scientist would probably be a distinguished molecular biologist or biochemist or another expert in some other specialty that Finney didn’t know a thing about.

Finney started by reviewing the basics of Darwinian evolution. He cruised the Internet until he located a synopsis of The Origin of Species. He took some notes and jotted down a few questions that immediately sprang to mind. Maybe this wouldn’t be so bad after all. Like a good lawyer, he traced Darwin’s research back to the original source and read a few sections of Darwin’s journal—The Voyage of the Beagle. The entire book was reproduced on the Internet. Intrigued, Finney turned to the chapter on the Galápagos Islands:

Considering that these islands are placed directly under the equator, the climate is far from being excessively hot; this seems chiefly caused by the singularly low temperature of the surrounding water, brought here by the great southern Polar current. Excepting during one short season, very little rain falls, and even then it is irregular; but the clouds generally hang low.

Finney read with interest Darwin’s description of the volcanic geology of the islands, the lava streams, the black sand, and the zoology. Darwin described the unique habitat and incredible variety of wildlife with zeal, reveling in his interaction with the indigenous creatures.

In Darwin’s concluding thoughts on the Galápagos, he speculated as to why each island had such distinct wildlife. The paragraph triggered a number of additional questions for Finney, and he scribbled more notes.

The only light which I can throw on this remarkable difference in the inhabitants of the different islands, is, that the very strong currents of the sea running in a westerly and W.N.W. direction must separate, as far as transportal by the sea is concerned, the southern islands from the northern ones; and between these northern islands a strong N.W. current was observed. . . . As the archipelago is free to a most remarkable degree from gales of wind, neither the birds, insects, nor lighter seeds, would be blown from island to island. . . . Reviewing the facts here given, one is astonished at the amount of creative force, if such an expression may be used, displayed on these small, barren, and rocky islands; and still more so, at its diverse yet analogous action on points so near each other.

Creative force, Finney thought. He now had a theme. Every good cross-examination needed a theme. He began scouring the Internet with increased enthusiasm. Darwin had been more help than Finney had anticipated.

At 8:00 p.m. Nikki called Wellington to find out whether he had solved chapter 2. Finney had posted a new series of Westlaw searches, and Nikki didn’t have a clue what they meant.

“The normal spot?” Wellington asked.

Nikki checked her watch. The nightlife wouldn’t really get started for a few more hours. She could do it over the phone, but the kid probably needed some encouragement.

“Sure,” Nikki said.

Wellington arrived later than Nikki, probably due to the fact that the Starbucks was actually about ten minutes closer to her place than to his. He wore a pair of khaki cargo shorts that thankfully weren’t as tight as the last pair, a button-down Hawaiian shirt that he had tucked in (contrary to every fashion dictate known to Nikki), and a pair of white boat shoes with no socks. He had his backpack slung over his shoulder and undoubtedly had a fresh supply of sharpened number two lead pencils as well as his computer and Judge Finney’s little book.

“’S up?” he said.

Nikki just shook her head. Some kids were better off not even trying to be cool.

“You need to untuck that shirt,” Nikki said. “That’s what’s up.”

Wellington looked mortified. “Why?”

Because I don’t want to be seen with the world’s biggest nerd. Because tucking your shirt in went out of fashion with the Backstreet Boys. “Because if this mission gets any more intense, you may have to carry. And you’ve got nowhere to hide your piece when your shirt’s tucked in. Plus, you don’t want to suddenly change styles as soon as you start packing, or people will notice.”

Wellington went white. “You’re kidding, right? I, um . . . I don’t even know how to use a gun.”

“I’m kidding,” Nikki said, “about everything but the shirt. If you untuck it, at least people might wonder if you have a weapon. That alone could come in handy someday.”

Wellington considered this as Nikki imagined that big cranium of his cranking through all the pros and cons. “Okay,” he said after a few seconds. He pulled his shirt out, the wrinkled tail hanging conspicuously exposed.

“You look dangerous,” Nikki said.

Since every table inside Starbucks was occupied, they took their drinks and Wellington’s pound cake into the Farnsworths’ minivan and cranked up the air-conditioning. The van had a wet-dog odor to it, though Nikki pretended not to notice. How does a guy worried about a few germs on a pen ignore the legions of deadly microbes generated by a slimy corgi?

“Did you work on this cipher?” Wellington asked between bites of pound cake and sips of Pellegrino water.

“I looked at it,” Nikki said, “but I was pretty busy investigating the speedy-trial cases.”

Wellington mumbled something that was hard to understand since he had a mouth full of cake. He pulled out some charts as Nikki took a sip of her iced mocha.

“Here’s the frequency analysis chart,” Wellington said after he swallowed. It looked exactly like the one Nikki had created on the Internet. “Notice anything?”

Other than the smell of a corgi and the fact that you can’t remember not to ask questions? Nikki shook her head. “Not really.”

“The percentages for the ciphertext match up almost exactly with the averages for the English language,” Wellington announced. He ran his finger along the chart. “There are a few exceptions, as you might expect, but look at some of these. A—7 percent in the ciphertext, 8 percent in the English language. D—4 percent in the ciphertext, 4 percent in the English language. E—14 percent in the ciphertext, 13 percent in the English language. I—8 percent in the ciphertext, 7 percent in the English language. See the pattern? The percentages are almost the same.”

It was hard to argue with Wellington on encryption, so Nikki just gave him an “Mmm-hmm” and took another shot of mocha. She felt stupid for not seeing it herself.

“Which means that we’re not dealing with a substitution cipher in this chapter. We’re most likely dealing with a transposition cipher.” Wellington turned to Nikki, his eyes expectant.

“Amazing,” Nikki said, though her inflection said, “Boring.” She didn’t bother asking what a transposition cipher was. She knew that would be point number two in Professor Wellington’s lecture.

“A transposition cipher is when the letters actually represent themselves but the order of the letters has been scrambled. Our job is to detect the pattern and unscramble them.” There was a pause in the seminar as Wellington took his last bite of pound cake, chased it with a gulp of Pellegrino, and then set the empty Starbucks bag he had used for a plate on the floor of the vehicle.

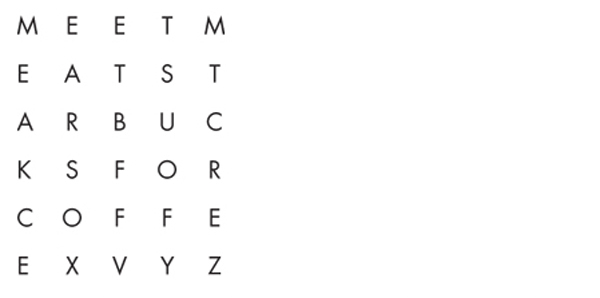

“Most people use a matrix to encrypt a transposition cipher.” Wellington pulled his small spiral notebook and pencil out of his backpack. He opened the notebook to a blank page. “Let’s say we want to write a message that says, ‘Meet me at Starbucks for coffee.’ I’ll use a matrix that is five letters wide and six letters long to encode it.”

Nikki watched as Wellington arranged the letters.

“Notice that I added some letters at the end as filler.” Wellington looked at Nikki, who nodded. “Now, instead of writing the letters in the code from left to right across the rows, we can write them from top to bottom along the columns,” he continued. “This will scramble them so that our message would read M-E-A-K-C-E-E-A-R-S-O-X and so on.”

“I see,” Nikki said, hoping the comment might speed things along.

“That’s just one form of transposition cipher, so I thought I would start there.”

Wellington flipped the pages in his notebook, showing Nikki a lot of different matrixes. “None of those worked,” he said. “So I tried some mathematical formulas to see if I could detect a pattern.”

He turned the page again. “Voilà! It was right under my nose the entire time.”

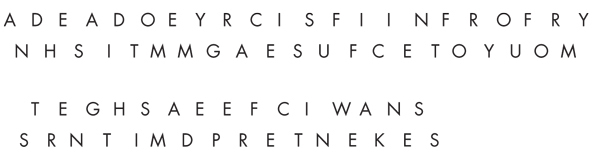

Nikki noticed the new pattern Wellington used on the page. “This is called the rail-fence cipher,” Wellington explained. “It’s so basic that I couldn’t believe I didn’t see it earlier. You just write the entire message on two different lines, alternating between them, and then you write the encoded message by copying the entire first line and then following it with the entire second line.”

Wellington turned toward Nikki. “Did you read chapter 2 in Finney’s book?”

“I skimmed it.”

“Good. Then you know it’s about the paralyzed man that some friends brought to Jesus for healing in a house so crowded that they had to drop the man in through the ceiling. Jesus pronounced forgiveness of the man’s sins, but the Pharisees were thinking that He had committed blasphemy. So to prove He had power to forgive sins, Jesus healed the man as well.”

“Which, of course, would lead any reasonable person to suspect a rail-fence cipher,” Nikki said sarcastically.

“Exactly,” Wellington said, proving once again that cipher experts didn’t do sarcasm. “Finney’s point was that too often we just operate on the physical plane, whether it’s our health or finances or whatever. But Jesus first dealt with the man’s spiritual condition and maybe wouldn’t have healed him at all if the Pharisees hadn’t been so critical. So Finney is saying we need to be cognizant of both dimensions—the spiritual and the physical—and the rail-fence cipher is a perfect picture of that because it only makes sense if you integrate the two planes together.”

“Did you solve the code?” Nikki asked. She avoided church so she wouldn’t get preached at. She didn’t need the Right Reverend Wellington Farnsworth making up for lost time in the minivan.

“Sorry. I just get into this stuff. It’s a verse from the apostle Paul after he had prayed without success for God to remove a thorn in his flesh.” He slid the paper over toward Nikki. “As you read, alternate from the top line to the bottom, and you’ll see what I mean.”

Nikki read the message, and like magic, it all made sense. She raised an eyebrow at Wellington. “Not bad,” she said.

Next, Nikki reached into the secret compartment of her black leather Fendi Spy bag. “Here are the letters from Finney’s latest Westlaw searches,” she said. She rattled them off to Wellington, who wrote them down using the rail-fence cipher.

He studied it for a minute before announcing the solution. “‘Need to know the location of Paradise Island. Is William Lassiter from governor’s office involved with show?’”

“That’s it?” Nikki asked. It seemed like they were working awfully hard for some pretty meager messages.

“At least it didn’t say to skip chapter 2,” Wellington noted.