CHAPTER 6

MENTAL HEALTH

The treatment of mental illness has become a major challenge for Americans. Symptoms of mental illness may be first seen by a primary care physician. Yet “primary care has woeful rates of diagnosing and treating mental health problems. . . . about 15 percent of people with a serious mental disorder receive what has been called ‘minimally adequate treatment’” (Sederer 2015). This failure to identify and treat mental health disorders is not attributable to bad doctors but to ineffective service models. Mental health conditions are more common than heart disease or diabetes—why, then, do primary care physicians not screen for them routinely, as they do for high blood pressure or blood sugar levels? Although mental illness can be diagnosed and often treated in primary care settings, few people who are referred to specialized mental health providers ever go. They may be deterred by the stigma of mental illness, a preference for one-stop healthcare shopping, a shortage of services, or the disproportionate denial of insurance claims for mental health services.

Consider the case of a 14-year-old girl with chronic asthma and post-traumatic stress disorder resulting from early childhood experiences (Sederer 2015). This patient may be seen by her primary care doctor for her asthma, but she might not receive treatment for the mental health disorder. Healthcare professionals and educational institutions recognize that primary care should better address patients’ mental health needs (American Academy of Family Physicians 2018).

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you will be able to

Discuss the serious mental health challenges facing Americans.

Discuss the serious mental health challenges facing Americans.

Illustrate the history of mental health treatment in the United States.

Illustrate the history of mental health treatment in the United States.

Compare the different types of mental health providers.

Compare the different types of mental health providers.

Outline the reasons for inequities in mental health treatment in the United States.

Outline the reasons for inequities in mental health treatment in the United States.

Discuss the difficulty of treating of mental health disorders in the United States.

Discuss the difficulty of treating of mental health disorders in the United States.

Describe the reasons why it is difficult to recruit mental health providers.

Describe the reasons why it is difficult to recruit mental health providers.

Recognize new, innovative methods for treating mental health.

Recognize new, innovative methods for treating mental health.

Mental health is a serious issue in the United States. About 44.7 million adults have some form of mental illness that may severely affect their quality of life or even become life-threatening. People who have a mental illness often have other chronic medical conditions as well, and on average, their life expectancies are 25 years less than those without a mental illness (Levine 2018). Moreover, mental illness is the third leading cause of disability and frequently leads to suicide (NIMH 2017). Suicide is one of the leading causes of death among young people, and more than 90 percent of children who die by suicide have a mental health condition. In addition, approximately 20 percent of those held in jails and prisons exhibit symptoms of mental illness. Mental illness costs the United States around $190 billion annually in lost earnings and more than $110 billion in total healthcare spending. The United States has the highest rate of death from mental illness of any industrialized country (Kamal 2017; NAMI 2019a).

THE HISTORY OF MENTAL HEALTH CARE

For thousands of years, mental illness was misunderstood. Historically, most people believed that mental illness was caused by demons or evil spirits. This belief was reflected in Jewish, Christian, and Islamic literature. As a result, treatments for mental illness included exorcism and the use of religious relics to cast out demons. People with mental health problems were often stigmatized and frequently punished or ostracized.

By the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, most of Western civilization had come to recognize mental illness as a type of medical illness, but unconventional (and, we now know, ineffective) treatments persisted. For instance, some people with mental illness were placed in cages and lowered into water. Others were spun around until they vomited. Cold water was sometimes poured over a patient’s head and hot water over their feet. Patients were given chemicals that induced seizures or insulin, which caused coma. Eventually, asylums were established for people with mental illness, with the idea that creating a safe environment would restore their sanity (Malcolm and Blumer 2016).

Asylums provided a means of controlling populations by removing the mentally ill from society. The first mental health asylum in the United States was organized in 1752 by Quakers (members of the Religious Society of Friends) in Philadelphia. The facility housed patients in rooms equipped with shackles in the basement of the Pennsylvania Hospital.

As discussed in chapter 5, for most of the nineteenth century, many people with mental illness either lived in the community or were cared for in public almshouses. During the first half of the twentieth century, patients’ length of stay in mental hospitals increased dramatically. Through the late 1800s, around 40 percent of patients eventually left these hospitals. By the twentieth century, however, the proportion of short-term cases decreased and the proportion of long-term patients increased. By 1910, the proportion of short-term patients fell to only 12.7 percent (Grob 1992).

Even as recently as the 1960s, care for the mentally ill remained inadequate; patients were often relegated to crowded and understaffed facilities (see sidebar). Treatments for mental illness frequently were untested folk remedies and often verged on the bizarre.

ST. ELIZABETHS HOSPITAL

ST. ELIZABETHS HOSPITAL

One of the oldest public mental health hospitals, St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, DC, provides an example of how such facilities operated in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Although St. Elizabeths was established with good intentions, a lack of funding and overwhelming demand resulted in inadequate mental health treatment for many poor people. Opened in 1855 as the first federally operated psychiatric hospital, St. Elizabeths sought to provide a better option for the treatment of the mentally ill. In the 1940s and 1950s, the institution treated as many as 8,000 each year. Eventually, St. Elizabeths became known as the “Government Hospital for the Insane.” At the same time, the hospital participated in controversial studies that treated the mentally ill with mind-altering drugs, truth serums, and forced lobotomies (Leshan 2016; Stamberg 2017).

In response to the wide variation in treatments for mental illness and uncertainty surrounding their effectiveness, in 1946 the US federal government passed the National Mental Health Act, which established and provided funds for the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Today, the NIMH “is the lead federal agency for research on mental illnesses, with a mission to transform the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses through basic and clinical research, paving the way for prevention, recovery, and cure.” The NIMH was extremely important in establishing proven methods of treating mental illness. With an annual budget of more than $1.6 billion in 2017 (NIMH 2018), the agency’s objectives include the following (NIMH 2017):

Define the mechanisms of complex mental disorders

Define the mechanisms of complex mental disorders

Chart mental illness trajectories to determine when, where, and how to intervene

Chart mental illness trajectories to determine when, where, and how to intervene

Strive for prevention and cures

Strive for prevention and cures

Strengthen the public health impact of NIMH-supported research

Strengthen the public health impact of NIMH-supported research

During the 1950s, concurrent with the development of antipsychotic drugs and financial pressures to better fund hospital or institutional care, treatment for the mentally ill was moved out of hospital settings to outpatient and community-based settings. The 1960s marked a significant transition from institutional hospital care to community health centers for mental health treatment in the United States. The number of mentally ill patients in hospitals fell from about 560,000 in the 1950s to 70,000 by 1994. In 1963, the Community Mental Health Act established community mental health centers and helped shift the delivery of mental health services even more to outpatient services. Coupled with advances in psychotropic medications, the law allowed many more patients to be treated in their communities (Torrey 1997).

Americans spend more than $186 billion per year on mental health treatment. Most of that money pays for prescription drugs (27 percent) and outpatient treatment (35 percent). Slightly less than 16 percent is spent on inpatient hospital treatment (Franki 2017). The number of mental health inpatient treatment beds in 2016 amounted to only 3 percent of the total number of inpatient hospital beds in the United States (Snook and Torrey 2018). At the same time, serious mental illness, including severe schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression, occurs at least 50 percent more often among the poor than among the general population. Some experts suggest that our mental health care system is still broken: About 25 percent of adults living in homeless shelters have a serious mental illness, and more than one-third of all adults with a serious mental illness do not obtain needed treatment (Kamal 2017).

An unfortunate side effect of moving so many patients out of hospitals was that by the 1970s, the mentally ill were incarcerated more often. In 2017, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics (an agency of the US Department of Justice), more than half of all prisoners suffered from a mental illness, and the three largest institutions providing psychiatric care were jails in New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago, where the mentally ill received inadequate treatment for their conditions (American Psychiatric Association 2020; Kozlowska 2015; Roth 2018). By 2014, prisons and jails housed ten times the number of people suffering from severe mental illness than state mental hospitals (Snook and Torrey 2018). One report indicated that 56 percent of those in state prisons, 45 percent in federal prisons, and 64 percent in local jails had a recent mental health problem (Kamal 2017).

DEBATE TIME

DEBATE TIME

Jails are not an appropriate place for the mentally ill. Yet frequently people are arrested for a crime triggered by a mental health crisis, jailed, and found incompetent to stand trial, but then they are kept in jail for long periods of time because of a lack of mental health facilities for prisoners. For example, Elle was arrested for sleeping in someone’s car in a garage and had opened the glove box. Bail was set at $50,000, as this was not her first arrest. Six months later, the judged ruled her incompetent to stand trial. Part of the delay was her erratic behavior and delusions. She stayed in jail for another eight months before she was treated at the state mental health hospital. After four months of treatment at the hospital, she was found competent and sent back to the judge, who dropped all charges except trespassing.

Although increased funding for mental health treatment may seem like an simple solution, what can communities do to better care for people with mental illness who are arrested?

The loss of state psychiatric hospitals may have limited treatment options for the severely mentally ill, who need inpatient care but lack the funds to pay for it. For low-income patients, Medicaid is often the only source of care. However, Medicaid does not pay for long-term mental health treatment. As a result, a high percentage of these patients use the emergency room (ER) as their primary source of healthcare. After these patients are seen in the ER, they are frequently sent back to their communities, and many become homeless (Raphelson 2017).

Community hospitals are not set up to be a solution for mental health treatment. Generally, they are not organized to care for patients needing more than 72 hours of immediate care. The low number of inpatient beds allocated for mental health patients forces people who are acutely mentally ill to wait for extended treatment. This situation often creates a devastating downward spiral effect, as patients’ mental health conditions deteriorate while they wait for treatment. People with untreated mental illness may act out, injure themselves, lose their jobs, or commit or be the victim of crimes. These actions lead to additional visits to the ER, homeless shelters, or prison (Snook and Torrey 2018).

Thirteen percent of patients who are admitted to community hospitals for mental illness are readmitted within 30 days (Kamal 2017). Most ER patients receive only temporary or urgent care and fail to obtain coordinated care from a primary care provider. In addition, of the many people with mental illnesses who are incarcerated each year, an estimated 15 percent of men and 30 percent of women have serious mental health concerns (NAMI 2020).

TYPES OF MENTAL HEALTH PROVIDERS

Many different types of providers care for people with mental illness. These providers vary by their level of education, scope of practice, and the services they can offer. The following are most common types of providers focusing almost exclusively on mental health (NAMI 2019b):

A psychiatrist is a medical doctor who has completed a residency in psychiatry. Psychiatrists can diagnose mental illnesses, prescribe and monitor medications, and provide therapy. They must be licensed in the state in which they practice and may be board certified by their professional association (e.g., American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology).

A psychiatrist is a medical doctor who has completed a residency in psychiatry. Psychiatrists can diagnose mental illnesses, prescribe and monitor medications, and provide therapy. They must be licensed in the state in which they practice and may be board certified by their professional association (e.g., American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology).

A psychologist holds a doctoral degree—either a doctor of philosophy (PhD) or a doctor of psychology (PsyD)—in psychology, counseling, or education. Psychologists use clinical interviews, psychological evaluations, and testing to assess and diagnose patients. They must be licensed in the state in which they practice.

A psychologist holds a doctoral degree—either a doctor of philosophy (PhD) or a doctor of psychology (PsyD)—in psychology, counseling, or education. Psychologists use clinical interviews, psychological evaluations, and testing to assess and diagnose patients. They must be licensed in the state in which they practice.

A psychiatric or mental health nurse practitioner may be a registered nurse (RN) with a master of science (MS) or doctor of philosophy (PhD) in nursing, specializing in psychiatry. Nurse practitioners provide assessment, diagnosis, and therapy. They must be licensed as RNs and may need to be supervised by a psychiatrist.

A psychiatric or mental health nurse practitioner may be a registered nurse (RN) with a master of science (MS) or doctor of philosophy (PhD) in nursing, specializing in psychiatry. Nurse practitioners provide assessment, diagnosis, and therapy. They must be licensed as RNs and may need to be supervised by a psychiatrist.

A licensed clinical social worker holds a master’s degree in social work (MSW). Social workers are trained to evaluate mental health, use therapeutic techniques, and provide case management and advocacy services. Licensure is required in most states.

A licensed clinical social worker holds a master’s degree in social work (MSW). Social workers are trained to evaluate mental health, use therapeutic techniques, and provide case management and advocacy services. Licensure is required in most states.

A counselor or therapist usually holds a master’s degree in a mental health discipline (e.g., counseling, marriage and family therapy). Counselors are trained to use therapeutic techniques to evaluate and treat patients. Licensure is required in some states.

A counselor or therapist usually holds a master’s degree in a mental health discipline (e.g., counseling, marriage and family therapy). Counselors are trained to use therapeutic techniques to evaluate and treat patients. Licensure is required in some states.

OWNERSHIP OF MENTAL HEALTH FACILITIES

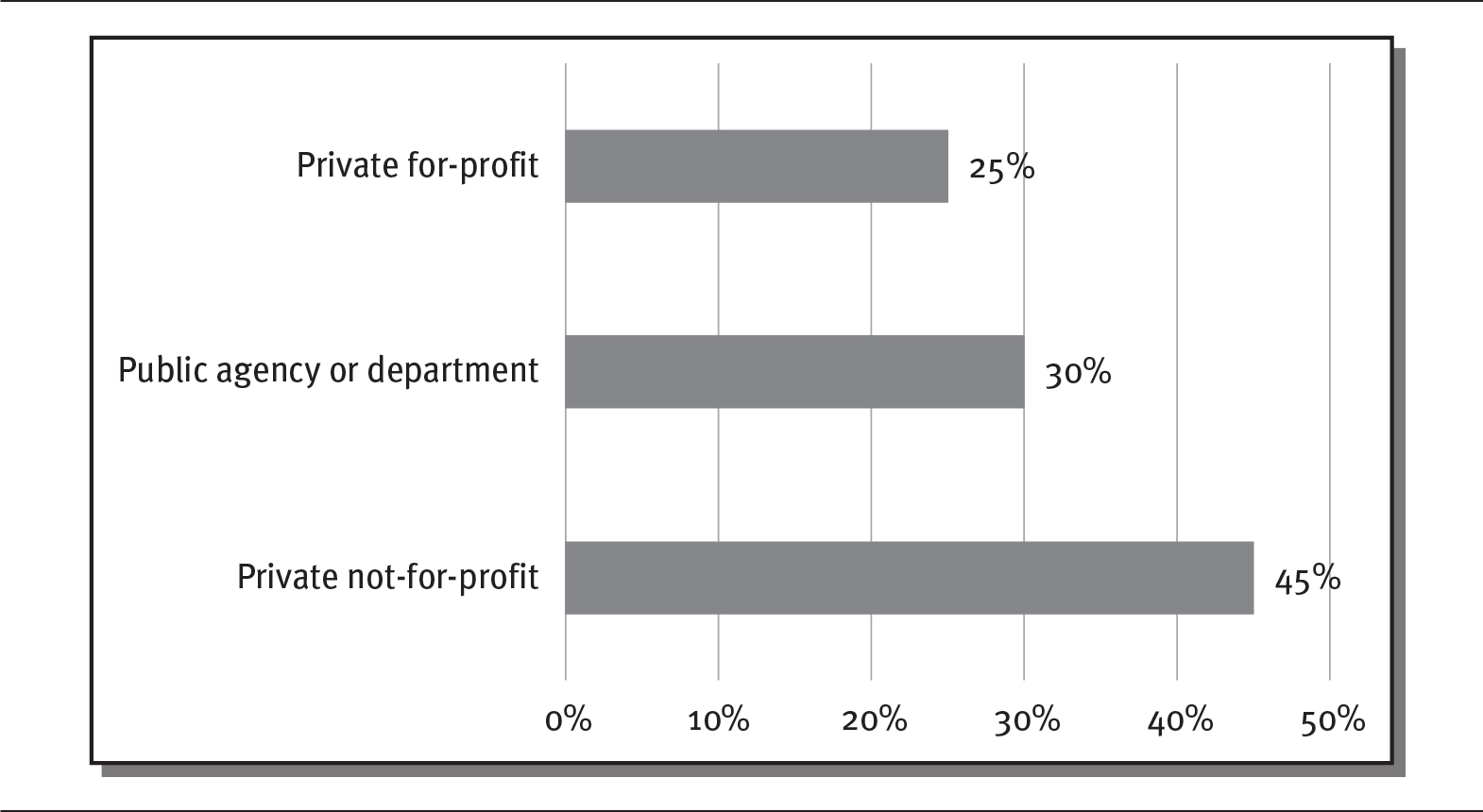

About three-quarters of mental health hospitals are not-for-profit or public institutions. Private not-for-profit facilities account for almost half of mental health hospitals, while 30 percent are owned by public (government) entities (see exhibit 6.1).

EXHIBIT 6.1 Ownership of Mental Health Hospitals, 2018

Details

The x-axis shows percentage from 0 to 50 in increments of 10 and the y-axis shows ownership. The details are as follows:

- Private-for-profit: 25 percent.

- Public agency or department: 30 percent.

- Private not-for-profit: 45 percent.

Source: Data from Statista (2020).

MENTAL HEALTH TREATMENT SETTINGS

Mental health treatment is offered in a variety of settings. More than one-third of treatment facilities provide only outpatient services, although many provide more than one level of care. For instance, many facilities provide a mix of inpatient, residential, and outpatient care. In addition, most facilities (58 percent) restrict the age groups that they treat (SAMHSA 2018).

Psychiatric care for the general public (excluding prisoners) that necessitates overnight treatment is provided in different types of settings, including specialized public and private psychiatric hospitals, psychiatric inpatient care in community hospitals, and licensed residential treatment units. Inpatient treatment is reserved mostly for patients with severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, mood disorders, major depression, suicidal ideation, and bipolar disorder (Kamal 2017).

In all, 692 psychiatric hospitals are in operation in the United States. This figure includes 206 public and 486 private facilities (SAMHSA 2018). Approximately 195 state-run psychiatric hospitals are in operation in the United States (NASMHPD 2020). Fourteen states have only one state psychiatric hospital (Parks and Radke 2014). Public psychiatric hospitals average more inpatient beds (182 per facility) than private facilities (73 per facility) (SAMHSA 2018).

STATE MENTAL HEALTH FACILITIES

State mental health facilities primarily serve those who enter the mental health system through the courts. Many state mental hospitals struggle financially as a result of budget cuts, which may affect the quality of care. For instance, when Florida enacted budget cuts of about $100 million to its state mental hospital system, some reported that this “turned state-run mental-health hospitals” into “treacherous warehouses where violence is out of control and patients can’t get the care they need” (Snook and Torrey 2018).

States’ underfunding of mental health has also led to the closure of many inpatient facilities without adequate increases in funding for alternative services. Since 2005, publicly funded inpatient psychiatric beds have dropped by 40 percent, to about 700 beds (Boston Globe 2016).

COMMUNITY HOSPITAL EMERGENCY ROOMS

The lack of psychiatric inpatient beds causes patients to seek treatment through ERs located in community hospitals, which often are not equipped to treat psychiatric emergencies. The psychiatric care that ERs can provide is fairly limited. ERs often do not have the time and expertise to treat those needing psychiatric care; as a result, patients may be kept in the ER for multiple days, until appropriate resources can be located (Kalter 2019). In fact, one survey indicated that 62 percent of ER doctors felt they could not provide appropriate psychiatric services. However, the demand for psychiatric care in ERs has grown significantly. For example, between 2006 and 2013, psychiatric visits to ERs increased more than 50 percent (Kennedy 2018). Most experts agree that the ER is not the best location for psychiatric care, as wait times are long, costs are high, and psychiatric and mental health treatment is often poor (Miller 2015).

COMMUNITY HEALTH CENTERS

More than 2,600 community health centers in the United States provide care for 27 million patients, many of whom have a need for some type of mental health treatment (Simmons 2018; SAMHSA 2018). Almost half (49 percent) of all community health center patients are covered by Medicaid, and about one-quarter (23 percent) have no insurance. Almost all community health center patients (92 percent) come from low-income families. About 10 percent of all visits to community health centers are for mental health services (Rosenbaum et al. 2018). Some community mental health centers are creating innovative partnerships to improve the health of those suffering from mental health issues (see sidebar).

PRIVATE MENTAL HEALTH HOSPITALS

As a result of the declining numbers of public hospital beds, many for-profit psychiatric treatment facilities have emerged. Private hospitals can provide more services and often more comprehensive care for those who can afford it. These hospitals also may provide scenic, quiet settings for treatments that might include gourmet meals and highly qualified healthcare professionals. Many of these firms, such as Acadia Healthcare (see sidebar), have grown rapidly and now operate across much of the United States.

Investment in private hospitals has increased. For instance, US HealthVest raised almost $100 million in capital to build psychiatric hospitals in New York and Georgia. For-profit psychiatric hospitals tend to provide high profits for their investors. For example, the largest for-profit provider of psychiatric care, Universal Health, recorded operating margins of 23 percent—more than twice that the 11 percent earned by general community hospitals (Sachdev 2016).

For many people, however, private, for-profit psychiatric care is inaccessible. Most for-profit facilities do not accept Medicaid, and care can cost upwards of $30,000 per month (Raphelson 2017). For example, a residential treatment program at the Gunderson Residence in Cambridge, Massachusetts, costs $1,350 per day, or $81,000 for a 60-day treatment period (Khazan 2018). These high costs allow only the wealthy to have access to these quality programs and exclude those who lack funds. Private, for-profit mental health services are often marketed as luxury facilities. For instance, one private facility describes its hospital as follows:

The Beach Cottage at Seasons in Malibu is a stand-alone facility that offers life-changing treatment for individuals suffering with mental health disorders. . . . Once admitted, clients are safely ensconced in a warm, beachy ambiance, with close-up ocean views, a private path to the beach, sumptuous meals prepared by our chefs, and 24-hour compassionate care from our staff. A typical day might begin with a beach walk followed by yoga and breakfast, and end around the fire pit with other clients, processing what you have learned and experienced that day. (Seasons in Malibu 2020)

Private facilities may be a good solution for those with the means to pay for them, but they do not provide solutions for many mentally ill patients.

ACADIA HEALTHCARE

ACADIA HEALTHCARE

Some private, for-profit psychiatric companies have expanded rapidly. Acadia Healthcare (www.acadiahealthcare.com), a for-profit psychiatric care provider based in Tennessee, operated 589 behavioral health facilities in 2019, with 18,000 beds in 40 states in the United States and the United Kingdom. Acadia provides services including inpatient psychiatric care, specialty treatment facilities, residential treatment centers, and outpatient clinics, bringing in annual revenues of around $3 billion. Large healthcare chains like Acadia are increasingly influencing the provision of mental health services across the United States. However, these private facilities are generally only available to those who can afford such care or have health insurance that covers these services.

RESIDENTIAL TREATMENT CENTERS

Residential treatment centers are another setting for psychiatric care. Residential treatment centers provide care in a less resource-intensive setting than inpatient care. These centers provide a more home-like environment with less medical involvement. Many patients leaving inpatient care may be placed in residential treatment centers. In fact, most recovery programs are residential centers with outpatient treatment options (see sidebar). Residential treatment may continue over long periods of time and often treats those with chronic psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or dual diagnoses (patients who have both a mental illness and a substance abuse disorder). These centers can be not-for-profit or for-profit.

DEBATE TIME Healthcare Homes for Mental Illness

DEBATE TIME Healthcare Homes for Mental Illness

Do we need new models of treatment for the mentally ill? Some states, such as Missouri, have begun to experiment with ways to better treat mental health problems. In 2012, Missouri created Community Mental Health Centers (CMHCs) to act as healthcare homes for those with mental illness. The centers combined mental health and primary care to provide more comprehensive treatment for those struggling with mental illness. By 2016, results from these CMHCs were very positive, as mental health patients’ overall health indicators improved significantly. For instance, their blood cholesterol levels decreased, diabetes was better controlled, and the use of emergency rooms and hospitalizations plummeted. In just three years, Missouri saved $98 million in healthcare costs (Levine 2018). Perhaps a more comprehensive effort like Missouri’s could be used across the United States to address the struggles of so many mentally ill patients. Why do you think more states do not use this approach and focus only on psychiatric care?

COMMUNITY HOSPITAL PSYCHIATRIC UNITS

A patient requiring hospitalization can use a facility dedicated only to psychiatric care or obtain care from community hospitals that offer psychiatric services. A number of community hospitals have dedicated psychiatric units dedicated to mental health, but many general hospitals that lack specialized mental health units also provide inpatient treatment for individuals with mental illnesses in “scatter beds” (inpatient beds outside a specialized psychiatric unit) and in their emergency departments (Lutterman, Shaw, and Fisher 2017).

About 25 to 30 percent of community hospitals have dedicated psychiatric units. These units provide the majority of inpatient hospital psychiatric care in the United States, measured by the number of admissions. The quality of care may vary, as psychiatric patients in community hospitals may not be treated by psychiatrists but by internal medicine specialists and other medical staff with limited training in psychiatry (Mark et al. 2010).

OUTPATIENT PSYCHIATRIC TREATMENT

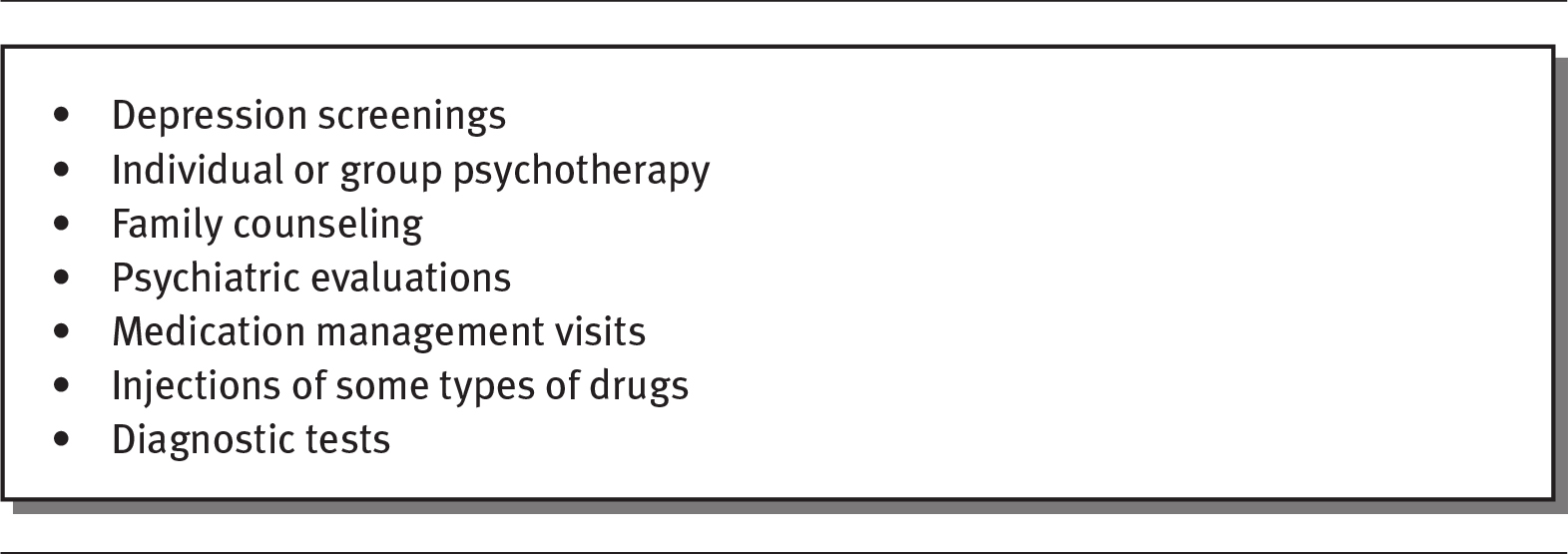

Outpatient services are those services that do not require a continuous stay of 24 hours or longer in a treatment facility. As with general hospital care, most psychiatric care has shifted to outpatient settings. More than 4 million people received some type of outpatient psychiatric treatment in 2016 (SAMHSA 2018). Outpatient treatments include a variety of services, such as those listed in exhibit 6.2.

EXHIBIT 6.2 Types of Mental Health Outpatient Treatments

Details

The details are as follows:

- Depression screenings

- Individual or group psychotherapy

- Family counseling

- Psychiatric evaluations

- Medication management visits

- Injections of some types of drugs

- Diagnostic tests

Source: Medicare.gov (2020).

SUBSTANCE ABUSE AND MENTAL ILLNESS

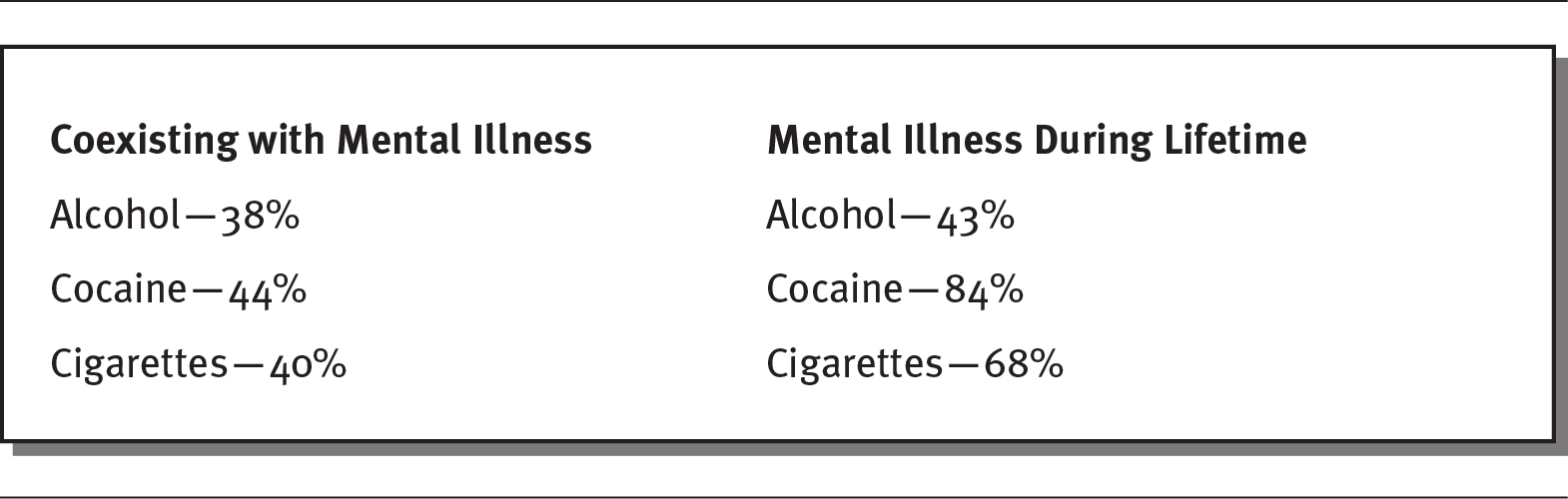

There is a strong connection between substance abuse and mental illness. About half of those with mental illness experience substance abuse problems. The use of illegal drugs during childhood and adolescence has also been shown to enhance the risk for mental illness; at the same time, mental health problems in young people increase their risk for later substance abuse. As a result, better treatment occurs when substance abuse and mental health are addressed simultaneously (National Institute on Drug Abuse 2020). As shown in exhibit 6.3, people with mental illness consume a large share of addictive substances when one considers that only about 24 percent of the US population in any given year has a diagnosable mental illness.

EXHIBIT 6.3 Share of Additive Substances Used by People with Mental Illness

Details

The details are as follows:

- Alcohol:

- Coexisting with mental illness: 38

- Mental illness during lifetime: 43

- Cocaine:

- Coexisting with mental illness: 44

- Mental illness during lifetime: 84

- Cigarettes:

- Coexisting with mental illness: 40

- Mental illness during lifetime: 68

Source: Data from NBER (2018).

Some drug use directly exacerbates mental health problems. For example, depression commonly occurs when crystal meth and alcohol begin to wear off (Foundations Recovery Network 2020). As a result of the connection between substance and abuse and mental illness, it is important to treat them jointly.

CHALLENGES IN MENTAL HEALTH CARE

SUPPLY OF PROVIDERS

The United States has a shortage of mental health providers. Decreasing availability of psychiatric medical residencies and low job satisfaction often deter people from entering the psychiatric professions. Because so few physicians are training in psychiatry, it is an aging profession: About 70 percent of practicing psychiatrists are over age 50, and 60 percent are 55 or older. At the same time, demand for mental health services is increasing (Japsen 2018). Almost every county in the United States has reported an unmet need for psychiatrists. Even in urban areas, people needing mental health treatment have difficulty getting an appointment for care. According to one study, only 12 percent of callers to a mental health facility in Boston were able to obtain an appointment with an initial call, and 23 percent never received an appointment even after calling twice (Davio 2018). By 2025, a significant shortage of psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, mental health counselors, and marriage and family therapists is predicted across the United States (NCHWA 2016).

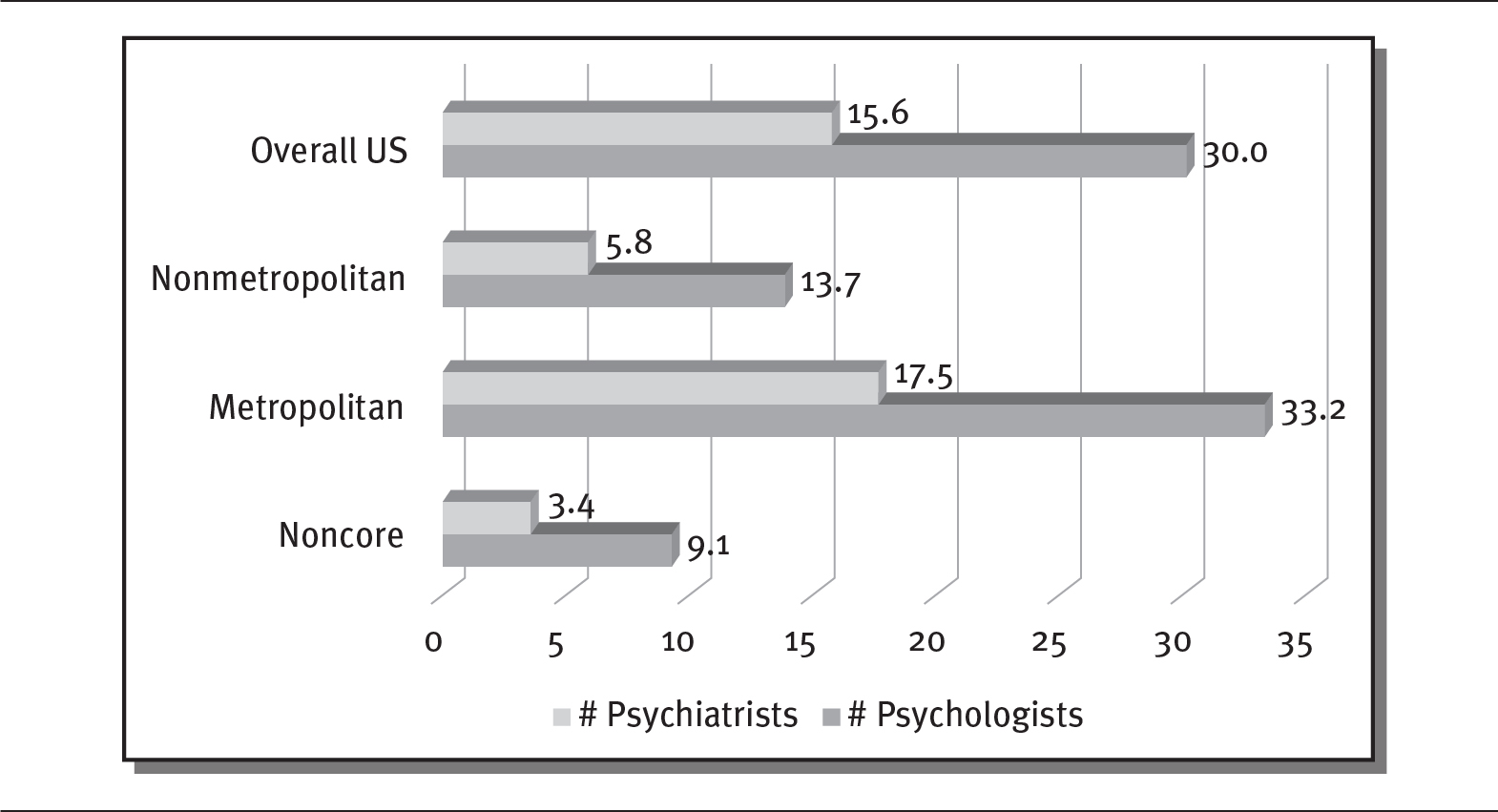

Accessing psychiatric care is even more challenging in rural areas. Most mental health providers reside in urban areas, and few live in rural areas (Butryn et al. 2017). Individuals with mental illness who reside in rural areas experience greater difficulty finding care. Most rural areas (65 percent) lack a psychiatrist, and almost half (47 percent) do not have any psychologists. This shortage has a direct impact on rates of drug abuse and suicide. As the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) states, “Suicide, drug abuse and addiction are certainly problems that affect all populations and all parts of the country, but both drug deaths and suicide deaths disproportionately affect rural America” (Willingham and Elkin 2018).

As shown in exhibit 6.4, smaller communities (referred to as “noncore” communities) and areas outside of metropolitan areas have almost one-third the number of key mental health providers. Even if there is a psychologist or psychiatrist available, given their low income levels and lack of transportation, people in rural areas still may not be able to access care (Willingham and Elkin 2018).

EXHIBIT 6.4 Behavioral Health Practitioners by County Type (providers per 100,000 people)

Details

The x-axis shows numbers of providers per 100,000 people from 0 to 35 in increments of 5. The y-axis shows number of psychiatrists and number of psychologists for various regions. The details are as follows:

- Overall US:

- Psychiatrists: 15.6

- Psychologists: 30

- Nonmetropolitan:

- Psychiatrists: 5.8

- Psychologists: 13.7

- Metropolitan:

- Psychiatrists: 17.5

- Psychologists: 33.2

- Noncore:

- Psychiatrists: 3.4

- Psychologists: 9.1

Note below chart reads as: Noncore counties are those counties where the major cities or clusters of cities have a population of less than 10,000 or there is no substantial population center.

Note: Noncore counties are those counties where the major cities or clusters of cities have a population of less than 10,000 or there is no substantial population center.

Source: Data from Willingham and Elkin (2018).

COST AND FUNDING OF MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES

States have cut more than $4 billion from their public mental health funding since 2008. Today, many people cannot afford to receive mental health services. According to one estimate, only 20 percent of youth and children who need mental health care receive it, and payments for psychiatric services are so low that many providers lose money on many of their services (Davio 2018). Because mental health providers feel that insurance companies do not reimburse them adequately, only 55 percent of psychiatrists accept insurance, and many require cash payments, which can amount to hundreds of dollars per session.

According to a study conducted by federal researchers, about half of patients who did not receive treatment for a mental health problem cited cost as a significant barrier to care. They indicated that they lacked insurance covering mental health treatment or could not afford the cost of treatment (GAO 2019). However, lowering the cost of mental health care to increase its use could decrease suicide rates in the United States (Garfield and Brueck 2018). Sadly, suicide rates for youth jumped 56 percent from 2007 to 2017, from 6.8 to 10.6 deaths per 100,000 people (Santhanam 2019).

STIGMA

Many people still feel threatened by and uncomfortable with those with mental illness. These feelings can foster discrimination and exclusion, creating a mental health stigma. This stigma can come from social or self-perceptions that lead to feelings of shame, prevent treatment, and result in poor mental health outcomes (Davey 2013). People often are reluctant to discuss their mental health issues because they fear embarrassing their family or even losing their job (Seervai and Lewis 2018). To obtain appropriate care, people with mental illness need to be able to discuss their illness openly without fear of social judgment. As one person who lost her mentally ill brother to suicide commented, “Fear of social rejection, ridicule, discrimination and judgment often keep people from sharing their struggle” (Warrell 2018).

Some efforts are being made to reduce the stigma. Professional athletes, for example, have been outspoken about their own struggles with mental illness in the hope of opening lines of communication and encouraging earlier treatment (Gabriel 2018). Likewise, Catholic bishops published a pastoral letter encouraging empathy and condemning the “unjust social stigma of mental illness,” which “is neither a moral failure nor character defect” (White 2018). In addition, some healthcare groups and primary care physicians are working together to integrate mental health care with primary care and to reduce stigma (AIMS Center 2020).

RACIAL AND ETHNIC DISPARITIES

The use of mental health services is much lower among African Americans, Asians, and Hispanics/Latinos than among whites (Kamal 2017). For example, more than 70 percent of African American youth with major depression do not receive treatment, and minority groups are less likely to receive a diagnosis and treatment for mental illness. In addition, they are much more likely to use the emergency room for mental health services than community mental health services (HHS 2019). Minorities often lack convenient access to quality mental health care, have higher levels of stigma against mental health treatment, have fewer financial resources and less health insurance coverage, and may have language barriers, all of which lower the use of mental health services among these populations. As a result, minorities receive lower-quality care and experience poorer outcomes related to mental illness (St. John 2016).

SUMMARY

The diagnosis and treatment of mental health has a profound impact on a wide swath of Americans. Historically, mental illness was misunderstood, and those suffering from it were often punished or shunned. By the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, most Western civilizations recognized mental disorders as medical illnesses, but ineffective and sometimes bizarre treatments persisted. Concentrating the mentally ill in asylums and public almshouses isolated them from their community.

Change came slowly to US institutions treating the mentally ill. As late as the 1960s, care for the mentally ill was inadequate, often provided in crowded and understaffed facilities. The creation of the National Institute of Mental Health in 1946, the development of antipsychotic drugs, and financial pressures prompted a shift from inpatient care to outpatient and community-based treatment. Today, the vast majority of expenditures on mental health care go toward prescription drugs and outpatient treatment.

An unfortunate side effect of the move to outpatient treatment and inadequate funding has been the imprisonment of many people with mental illness. About half of all prisoners in the United States have a psychiatric disorder. The three largest institutions providing psychiatric care are jails in New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago.

A variety of mental health providers exist. Most provide therapy, assessment, and diagnosis. The most commonly used mental health providers are psychiatrists and psychologists, but many others provide care, such as psychiatric nurse practitioners, social workers, and counselors and therapists.

Most organizations that provide mental health services are not-for-profit facilities; slightly less than 20 percent are for-profit institutions. A majority of mental health providers offer a mix of inpatient and outpatient care. Inpatient care can be provided in a variety of settings. It is used mostly for those suffering from schizophrenia, mood disorders, major depression, and bipolar disorder.

All states have at least one state mental health hospital. State psychiatric hospitals primarily serve those coming from the court system. Underfunding has led to long waits for care and increased use of emergency rooms for the mentally ill. Community health centers have also filled a need for many.

The wealthy have many options for mental health treatment. Many for-profit companies offer luxury facilities with extensive treatment options, but at very high costs.

Community hospitals offer psychiatric services in dedicated units, in scattered beds, and in their emergency rooms. A majority of inpatient admissions to psychiatric units take place in community hospitals.

Many individuals struggle with both substance abuse and mental illness, and there is a direct correlation between them. Both issues need to be treated jointly.

The United States faces a lack of mental health providers as a result of the decreasing number of psychiatric residencies, low job satisfaction, and lower earning potential. A majority of psychiatrists today are over the age of 55. Almost all counties in the United States report a need for more mental health services, although people in rural areas experience greater difficulty accessing services.

The lack of public funding and the high costs of care create significant barriers to mental healthcare and treatment. Many mental health providers do not accept insurance and require individuals to pay for services out of pocket. In addition to cost, some people feel threatened by and uncomfortable with others with mental illness. This often results in discrimination and exclusion, creating a stigma toward mental illness.

QUESTIONS

- What were some of the treatments given to the mentally ill during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries? How do we regard those treatments today?

- What was the original function of asylums?

- When was the National Institute of Mental Health created, and why?

- Why did the number of people hospitalized for mental illness decline in the 1960s?

- What are the side effects of people with mental illness leaving hospitals?

- What is the difference between a psychiatrist and a psychologist?

- What is the ownership structure of most mental health treatment providers in the United States?

- Why are state mental health facilities struggling financially?

- If people cannot obtain care from mental health providers as a result of lack of funds or limited services, where do they go for care?

- What factors contribute to the declining number of psychiatrists in the United States?

ASSIGNMENTS

- Locate the website of a private not-for-profit mental health provider, a private for-profit mental health provider, and a state mental health agency. Describe the differences among them.

- Read the following article about differences in funding for mental health treatment by state: “Funds for Treating Individuals with Mental Illness: Is Your State Naughty or Nice?,” Mental Illness Policy Org, December 17, 2017, at https://mentalillnesspolicy.org/national-studies/funds-for-mental-illness-is-your-state-generous-or-stingy-press-release.html. Prepare to speak to your group about the following questions:

- Why are there such large funding differences among states?

- What impacts on physical and mental health would you predict in the states that spend the most? The least?

- Can you find any evidence to show that greater funding decreases opioid use and incarceration?

CASES

STRUGGLING WITH MENTAL HEALTH

My name is Tim and I am 30 years old. I was diagnosed with depression and anxiety when I turned 21, but it seems like I have been struggling with anxiety my whole life. At times, my depression and anxiety overwhelm me and make me feel hopeless. In the past decade, I have tried 16 different psychiatric medications and currently take four. I have also had four long-term individual therapists. I would have liked to have maintained my relationships with them, but I ran out of insurance coverage and had to seek alternatives. A couple of times, things got too challenging and I was hospitalized, once for three weeks. I am afraid that I have few insurance benefits left, which makes me very anxious. I also want to say that I have a mental illness, but I am afraid of the stigma that comes with it.

Discussion Questions

- What are the major challenges that Tim faces?

- What steps could Tim take to improve his mental health?

- What do you think American society could do to improve mental health treatment?

JAIL FOR THE MENTALLY ILL

Travis was jailed on charges that he broke into his father’s home to steal food. His family often found him delusional: he said that he could hear voices, and he believed that tiny robots had been implanted under his skin. One day, his father returned home to find the front door broken, and he called the police. Even though his father did not want his son to be arrested, the police took him to jail and charged him with a class B felony. Travis languished in jail for 18 months until a judge found him incompetent to face trial. During his incarceration, Travis refused to comply with many of the rules, and once he threw his plate of food at a guard, earning him time in solitary confinement. During the year and a half that he was incarcerated, his delusions increased, and he received very little mental health treatment.

Discussion Questions

- What problems result from incarcerating people with mental illness?

- What could governments do to provide better treatment for people with mental illness in jails?

REFERENCES

Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions (AIMS) Center. 2020. “Collaborative Care.” Accessed April 20. https://aims.uw.edu/collaborative-care.

American Academy of Family Physicians. 2018. “Mental Health Care Services by Family Physicians.” Position Paper. Accessed April 20, 2020. www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/mental-services.html.

American Psychiatric Association. 2020. “Criminal Justice.” Accessed June 5. www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/advocacy/federal-affairs/criminal-justice.

Boston Globe. 2016. “State Must Deal with the Grim Aftermath of Psychiatric Hospital Closings.” Published July 7. www.bostonglobe.com/opinion/editorials/2016/07/06/state-must-deal-with-grim-aftermath-psychiatric-hospital-closings/Fl0BRFjZaY84QidgjHfODP/story.html.

Butryn, T., L. Bryant, C. Marchionni, and F. Sholevar. 2017. “The Shortage of Psychiatrists and Other Mental Health Providers: Causes, Current State, and Potential Solutions.” International Journal of Academic Medicine 3 (1): 5–9.

Davey, G. 2013. “Mental Health & Stigma.” Psychology Today. Published August 20. www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/why-we-worry/201308/mental-health-stigma.

Davio, K. 2018. “Single-Payer System Is the Solution for Mental Healthcare, Panelists Say.” American Journal of Managed Care. Published May 7. www.ajmc.com/conferences/apa-2018/singlepayer-system-is-the-solution-for-mental-health-care-panelists-say.

Foundations Recovery Network. 2020. “The Connection Between Mental Illness and Substance Abuse.” Accessed April 20. www.dualdiagnosis.org/mental-health-and-addiction/the-connection/.

Franki, R. 2017. “Outpatient Care 35% of Mental Health Costs and Growing.” Clinical Psychiatry News/MDedge. Published July 7. www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/142102/business-medicine/outpatient-care-35-mental-health-costs-and-growing.

Gabriel, E. 2018. “NBA Stars Join Fight Against Stigma Surrounding Mental Illness.” CNN. Published March 28. www.cnn.com/2018/03/02/health/nba-mental-health-stigma/index.html.

Garfield, L., and H. Brueck. 2018. “There May Be One Big Reason Suicide Rates Keep Climbing in the U.S., According to Mental-Health Experts.” Business Insider. Published June 9. www.businessinsider.com/anthony-bourdain-kate-spade-suicide-rate-mental-healthcare-costs-2018-6.

Grob, G. 1992. “Mental Health Policy in America: Myths and Realities.” Health Affairs 11 (3): 7–22.

Japsen, B. 2018. “Psychiatrist Shortage Escalates as U.S. Mental Health Needs Grow.” Forbes. Published February 25. www.forbes.com/sites/brucejapsen/2018/02/25/psychiatrist-shortage-escalates-as-u-s-mental-health-needs-grow/#36b702c51255.

Kalter, L. 2019. “Treating Mental Illness in the ED.” Association of American Medical Colleges. Published September 3. www.aamc.org/news-insights/treating-mental-illness-ed.

Kamal, R. 2017. “What Are the Current Costs and Outcomes Related to Mental Health and Substance Abuse Disorders?” Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker. Published July 31. www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/current-costs-outcomes-related-mental-health-substance-abuse-disorders/#item-start.

Kennedy, M. 2018. “‘Failing Patients’: Baltimore Video Highlights Crisis of Emergency Psychiatric Care.” National Public Radio, April 29. www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2018/04/29/599892160/failing-patients-baltimore-video-highlights-crisis-of-emergency-psychiatric-care.

Khazan, O. 2018. “Trump’s Call for Mental Institutions Could Be Good.” The Atlantic. Published February 23. www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2018/02/mental-institutions/554015/.

Kozlowska, H. 2015. “Should the U.S. Bring Back Psychiatric Asylums?” The Atlantic. Published January 27. www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/01/should-the-us-bring-back-psychiatric-asylums/384838/.

Leshan, B. 2016. “The Lobotomist: Ghosts of St. Elizabeths Hospital.” WUSA. Published May 19. www.wusa9.com/article/news/local/the-lobotomist-ghosts-of-st-elizabeths-hospital/204464983.

Levine, D. 2018. “What Are the Advantages of Health Homes for Mental Healthcare?” U.S. News & World Report. Published February 23. https://health.usnews.com/health-care/patient-advice/articles/2018-02-23/what-are-the-advantages-of-health-homes-for-mental-health-care.

Lutterman, T., R. Shaw, and W. Fisher. 2017. “Trend in Psychiatric Inpatient Capacity, United States and Each State, 1970 to 2014.” National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, Assessment No. 10. Published August. www.nri-inc.org/media/1319/tac-paper-10-psychiatric-inpatient-capacity-final-09-05-2017.pdf.

Malcolm, L., and C. Blumer. 2016. “Madness and Insanity: A History of Mental Illness from Evil Spirits to Modern Medicine.” ABC Health. Published August 2. www.abc.net.au/news/health/2016-08-02/mental-illness-and-insanity-a-short-cultural-history/7677906.

Mark, T., R. Vandivort-Warren, P. Owens, J. Buck, K. Levit, R. Coffey, and C. Stocks. 2010. “Patient Discharges in Community Hospitals With and Without Psychiatric Units: How Many and for Whom?” Psychiatric Services 61 (6): 562–68.

Medicare.gov. 2020. “Your Medicare Coverage: Mental Health Care (Outpatient).” Accessed April 20. www.medicare.gov/coverage/outpatient-mental-health-care.html.

Miller, A. 2015. “What to Do During a Mental Health Crisis.” U.S. News & World Report. Published July 21. https://health.usnews.com/health-news/best-hospitals/articles/2015/07/21/what-to-do-during-a-mental-health-crisis.

National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). 2020. “Jailing People with Mental Illness.” Accessed April 20. www.nami.org/learn-more/public-policy/jailing-people-with-mental-illness.

———. 2019a. “Mental Health by the Numbers.” Updated September. www.nami.org/learn-more/mental-health-by-the-numbers.

———. 2019b. “Types of Mental Health Professionals.” Updated April. www.nami.org/Learn-More/Treatment/Types-of-Mental-Health-Professionals.

National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD). 2020. “State Hospital Organizations.” Accessed April 20. www.nasmhpd.org/content/state-hospital-organizations.

National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). 2018. “Mental Illness and Substance Abuse.” www.nber.org/digest/apr02/w8699.html.

National Center for Health Workforce Analysis (NCHWA). 2016. “National Projections of Supply and Demand for Selected Behavioral Health Practitioners: 2013–2025.” Published November. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/health-workforce-analysis/research/projections/behavioral-health2013-2025.pdf.

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). 2018. “FY 2019 Budget.” Accessed April 20, 2020. www.nimh.nih.gov/about/budget/cj2019_156766.pdf.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. 2020. “Common Comorbidities with Substance Use Disorders.” Updated April. www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/common-comorbidities-substance-use-disorders/part-1-connection-between-substance-use-disorders-mental-illness.

———. 2017. “The NIH Almanac.” Reviewed February 17. www.nih.gov/about-nih/what-we-do/nih-almanac/national-institute-mental-health-nimh.

Parks, J., and A. Radke, eds. 2014. “The Vital Role of State Psychiatric Hospitals.” National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, Technical Report. Published July. www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/The%20Vital%20Role%20of%20State%20Psychiatric%20HospitalsTechnical%20Report_July_2014.pdf.

Raphelson, S. 2017. “How the Loss of U.S. Psychiatric Hospitals Led to a Mental Health Crisis.” National Public Radio. Published November 30. www.npr.org/2017/11/30/567477160/how-the-loss-of-u-s-psychiatric-hospitals-led-to-a-mental-health-crisis.

Rosenbaum, S., J. Tolbert, J. Sharac, P. Shin, R. Gunsalus, and J. Zur. 2018. “Community Health Centers: Growing Importance in a Changing Healthcare System.” Kaiser Family Foundation. Published March 9. www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/community-health-centers-growing-importance-in-a-changing-health-care-system/.

Roth, A. 2018. Insane: America’s Criminal Treatment of Mental Illness. New York: Basic Books.

Sachdev, A. 2016. “For-Profit Psychiatric Care Firm Says It’s Filling Gap in the Chicago Area.” Chicago Tribune. Published July 1. www.chicagotribune.com/business/ct-psychiatric-hospital-northbrook-0703-biz-20160701-story.html.

Santhanam, L. 2019. “Youth Suicide Rates Are on the Rise in the US.” PBS NewsHour. Published October 18. www.pbs.org/newshour/health/youth-suicide-rates-are-on-the-rise-in-the-u-s.

Seasons in Malibu. 2020. “Seasons in Malibu Mental Health Treatment Center.” Accessed June 5. https://seasonsmalibu.com/treatment-programs/mental-health-treatment-facilities/.

Sederer, L. 2015. “Tinkering Can’t Fix the Mental Healthcare System.” U.S. News & World Report. Published March 20. www.usnews.com/opinion/blogs/opinion-blog/2015/03/20/fixing-the-mental-health-system-requires-disruptive-innovation.

Seervai, S., and C. Lewis. 2018. “Listening to Low-Income Patients: Mental Health Stigma Is a Barrier to Care.” Commonwealth Fund. Published May 20. www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/publication/2018/mar/listening-low-income-patients-mental-health-stigma-barrier-care.

Simmons, A. 2018. “NACHC Statement on the FY 2018 Omnibus Appropriations.” National Association of Community Health Centers. Published March 23. www.nachc.org/news/nachc-statement-on-the-2018-omnibus-legislation-passed-by-congress/.

Snook, J., and E. F. Torrey. 2018. “America Badly Needs More Psychiatric-Treatment Beds.” National Review. Published February 23. www.nationalreview.com/2018/02/america-badly-needs-more-psychiatric-treatment-beds/.

Stamberg, S. 2017. “Architecture of an Asylum Tracks History of U.S. Treatment of Mental Illness.” National Public Radio. Published July 6. www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2017/07/06/535608442/architecture-of-an-asylum-tracks-history-of-u-s-treatment-of-mental-illness.

Statista. 2020. “Number of Psychiatric Hospitals in the U.S. in 2018 by Operation Type.” Accessed June 5. www.statista.com/statistics/712645/psychiatric-hospitals-number-in-the-us-by-operation-type/.

St. John, T. 2016. “8 Reasons Racial and Ethnic Minorities Receive Less Mental Health Treatment.” Arundel Lodge Behavioral Health. Published August 2. www.arundellodge.org/8-reasons-cultural-and-ethnic-minorities-receive-less-mental-health-treatment/.

Substance Abuse and Mental Services Administration (SAMHSA). 2018. “National Mental Health Services Survey: 2018, Data on Mental Health Treatment Facilities.” Published October. www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NMHSS-2018.pdf.

Torrey, E. F. 1997. Out of the Shadows: Confronting America’s Mental Illness Crisis. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). 2019. “Minority Mental Health Awareness Month—July.” Office of Minority Health. Published July 1. www.minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/content.aspx?ID=9447.

US Government Accountability Office (GAO). 2019. “Behavioral Health: Research on Health Care Costs of Untreated Conditions Is Limited.” Report to Congressional Requesters. Published February. www.gao.gov/assets/700/697178.pdf.

Warrell, M. 2018. “The Rise and Rise of Suicide: We Must Remove the Stigma of Mental Illness.” Forbes. Published June 9. www.forbes.com/sites/margiewarrell/2018/06/09/the-rise-and-rise-of-suicide-we-must-remove-the-stigma-of-mental-illness/#42ebf9b77526.

White, C. 2018. “California Bishops Call for End to Social Stigma Around Mental Illness.” Crux. Published May 2. cruxnow.com/church-in-the-usa/2018/05/02/california-bishops-call-for-end-to-social-stigma-around-mental-illness/.

Willingham, A., and E. Elkin. 2018. “There’s a Severe Shortage of Mental Health Professionals in Rural Areas: Here’s Why That’s a Serious Problem.” CNN. Published June 20. www.cnn.com/2018/06/20/health/mental-health-rural-areas-issues-trnd/index.html.